ABSTRACT

This study examined the effectiveness of child-centered group play therapy (CCGPT) and narrative therapy in reducing separation anxiety disorder (SAD) and boosting social-emotional behaviours in early childhood (2.5-4-year-olds). An 8-week-randomized controlled trial design with three intervention groups, i.e. CCGPT, narrative therapy, and a combination of both interventions (i.e. combined group), and one control group that provided data at a pre-test and post-test, was adopted. A total of 48 children who showed signs of SAD participated in the study. Results showed that compared to the control group, CCGPT and combined group interventions showed a lower separation anxiety level. Children in all three intervention groups showed lower behavioural problems and higher prosocial behaviours than the control group. The findings suggest that the three interventions could be effective selective psychotherapy methods to promote social-emotional competencies. The CCGPT and combined group, particularly, were effective psychotherapy methods for reducing SAD in early childhood.

Introduction

The experience of distress upon separation or fear of separation from the child’s attachment figures, most commonly parents/caregivers, is an attachment behaviour and normative experience in which children experience negative feelings or emotions such as sadness, loneliness, or loss (Bowlby, Citation1973; Dabkowska, Citation2012). Symptoms of separation anxiety decrease for most children after two years of age, although they may continue throughout childhood and adolescence (Brand, Wilhelm, Kossowsky, Holsboer-Trachsler, & Schneider, Citation2011). Separation anxiety disorder (SAD; DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) is characterized by an extreme of otherwise developmentally normal anxiety expressed by excessive worry, concern, and even dread of the real or anticipated separation from attachment figures (Ramsawh, Chavira, & Stein, Citation2010; for a review see Wang et al., Citation2017). Even though separation anxiety is a developmentally appropriate phenomenon, SAD manifests with inappropriate intensity or the inappropriateness of context and age (Feriante & Bernstein, Citation2021).

SAD is the most frequently experienced childhood anxiety disorder (approximately 4%), has the earliest age of onset (preschool age, 2–5-year-olds), and can persist into adulthood (Angotti, Hamilton, & Kouchi, Citation2022; APA, Citation2013). SAD impairs flexibility and the confidence of children in independent interaction and may complicate age-normative developmental activities such as sleeping. It can also be a decisive factor in hindering the development of socio-emotional competencies, characterized by children’s capacity to have socially adequate reactions and regulate their emotions during social situations. SAD can significantly impact a child’s developmental trajectory if it leads to avoidance of specific places, activities, and experiences crucial for healthy social-emotional development (Ehrenreich, Santucci, & Weiner, Citation2008). Children diagnosed with SAD often fear that something catastrophic might happen when separated from an attachment figure leading to a refusal to participate in developmentally appropriate activities with peers (Ehrenreich et al., Citation2008). SAD can not only cause negative effects within areas of social and emotional functioning, adjustment, well-being, mental health, and academic achievement in childhood, but is also a significant risk factor for anxiety disorders (including panic disorder), depression, substance abuse, as well as physical health later in life (e.g. Kossowsky et al., Citation2013; Milrod et al., Citation2014; Orgilés, Penosa, Morales, Fernández-Martínez, & Espada, Citation2018; Vaughan, Coddington, Ahmed, & Ertel, Citation2017).

Despite substantial advances in knowledge and understanding of SAD in childhood, its high prevalence, early onset, and potential long-term effects and prognosis, it is still poorly recognized and undertreated (Feriante & Bernstein, Citation2021; Vaughan et al., Citation2017). There is a significant gap in the literature regarding evidence-based practice guidelines for SAD in early childhood (e.g. Milos & Reiss, Citation1982; Milrod et al., Citation2014; Swan, Kaff, & Haas, Citation2019). Effective early interventions targeting young children with SAD could promote their social-emotional competencies and prevent the onset of significant distress, future impairment, and mental disorders such as depression in adolescence and adulthood (Brewer & Sarvet, Citation2011). The present study hypothesizes that child-centered group play therapy (CCGPT) and narrative therapy as therapeutic tools would reduce separation anxiety levels in preschool children. Consequently, in the present study, we discuss CCGPT and narrative therapy in pediatric psychopathology and examine the effectiveness of these therapies in reducing SAD and promoting social-emotional behaviours in early childhood.

Separation anxiety disorder (SAD) and social-emotional behaviours in early childhood

A complex interaction of biological and genetic vulnerability, temperament characteristics, negative environmental influences and attachment experiences, the psychopathology of parents, and adverse sociocultural factors can all play a part in the etiology of SAD (Pine & Grun, Citation1999). The study of environmental risk factors for the development of SAD in children has focused on the interactions between parents/caregivers and children. According to attachment theory (Bowlby, Citation1973), i.e. a psychological approach that describes the development of mental representations, children’s early experiences with their principal caregiver will form an internal working model of attachment. Over time, these mental representations can predict children’s behaviour in various ways. They can influence how the child interacts and builds relationships with others, and explain different behaviours and expectancies in new social environments (Stubbs, Citation2018). These mental representations can support children’s prosocial behaviour (i.e. the ability to voluntarily act in a positive, accepting, helpful, sharing, and cooperative manner) by giving a ‘roadmap’ of how to meet the needs of others and by encouraging a view of others as worthy of care, arousing altruistic motivation to meet their needs (Gross, Stern, Brett, & Cassidy, Citation2017).

Anxiety caused by separation from the principal attachment figures in early childhood is natural and adaptive. Nevertheless, if this emotional state continues excessively into childhood and adolescence, it significantly affects daily activities and developmental tasks (Dabkowska, Araszkiewicz, Dabkowska, & Wilkosc, Citation2011). A longitudinal study (Copeland, Angold, Shanahan, & Costello, Citation2014) has shown that the frequency of lifetime prevalence of SAD is 5% from childhood until early adulthood. Physical symptoms associated with SAD include headaches, abdominal symptoms such as nausea or vomiting, and heart palpitations (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Children with SAD seem to be unable to function while their principal caregivers are absent. They may experience social withdrawal, apathy, sadness, or difficulty in concentrating on tasks or play, leading to low academic achievement and social isolation later on (Dabkowska, Citation2012).

Children who are socially and emotionally competent gain the skills and knowledge needed to build secure interpersonal relationships, regulate their emotions, cope with challenges, solve problems, and better adjust to preschool (Koivula, Turja, & Laakso, Citation2020; Nix, Bierman, Domitrovich, & Gill, Citation2013). For example, prosocial behaviour has been associated with many factors of children’s well-being, such as positive peer relationships and academic achievements (Arnold, Kupersmidt, Voegler-Lee, & Marshall, Citation2012; Caputi, Lecce, Pagnin, & Banerjee, Citation2012; Paulus, Citation2018). However, SAD can lead to deficiencies in several social and emotional domains critical to children’s healthy development. For example, children with SAD often cannot stay in preschool, avoid interpersonal contact, have difficulty entering and sustaining play with peers, and are much less likely to exhibit prosocial behaviours (Scharfstein & Beidel, Citation2015; Swan et al., Citation2019). These children often have fewer close friends, difficulty forming friendships, poor contact with peers, and lower quality peer interactions (Scharfstein, Alfano, Beidel, & Wong, Citation2011), and often experience excessive sadness, loneliness, anxiety, and fear (Dabkowska, Citation2012).

Child-centered group play therapy (CCGPT)

Play, a spontaneous, fun, voluntary, and non-goal-oriented activity (Yogman et al., Citation2018), is part of our evolutionary heritage, fundamental to health, and an opportunity to practice and hone the skills required for living in a complex world (Toub, Rajan, Golinkoff, & Hirsh-Pasek, Citation2016). Early learning and play are fundamentally social activities (Pellis, Pellis, & Bell, Citation2010), promote the development of social-emotional skills, language, and thought, and contribute to school readiness (Yogman et al., Citation2018).

CCGPT is a relationship-based group counselling approach based on the theoretical framework developed by Carl Rogers (Citation1961) and the developmental interpretation of person-centered therapy introduced by Axline (Citation1969). According to Axline (Citation1969), CCGPT is a ‘non-directive therapeutic experience with the added element of contemporary evaluation of behaviour plus the reaction of personalities upon one another’ (p. 26). CCGPT can be a practical therapeutic approach for decreasing SAD in early childhood (Goodyear-Brown & Andersen, Citation2018). It allows children to improve their language expression and reveal their thoughts, emotions, feelings, and experiences that they consider as threats to them. Because the group play therapist represents and encourages relationships and attitudes between group members, as well as individual processes and experiences, children learn about their own and their group members’ intentions, values, and emotional states (Goodman & Dent, Citation2017; Goodyear-Brown & Andersen, Citation2018). Play is a necessary means of improving self-confidence (Baggerly & Parker, Citation2005), anxiety (Islaeli, Yati, & Fadmi, Citation2020), social skills (Su & Tsai, Citation2016), resilience, social-emotional competencies (Cheng & Ray, Citation2016), and behaviour problems (Meany-Walen, Teeling, Davis, Artley, & Vignovich, Citation2016; Swank, Cheung, & Williams, Citation2018). Studies have shown that CCGPT techniques have effectively enhanced early childhood social-emotional competencies, including emotional expression, problem-solving, and friendship skills that are crucial for children’s adaptive functioning (e.g. Cheng & Ray, Citation2016; Chinekesh, Kamalian, Eltemasi, Chinekesh, & Alavi, Citation2014; Han, Lee, & Suh, Citation2017; Swan et al., Citation2019; Swank et al., Citation2018). CCGPT techniques have also been found to reduce separation anxiety symptoms in early childhood (e.g. Dousti, Pouyamanesh, Aghdam, h, & Jafari, Citation2017; Goodyear-Brown & Andersen, Citation2018; Milos & Reiss, Citation1982; Swan et al., Citation2019). For example, Swan et al. (Citation2019) found that preschool children who participated in CCGPT exhibited decreased separation anxiety symptoms and fewer problematic classroom behaviours.

Narrative therapy

Narrative therapy can be a strategy for working with children in recreational, educational, and emotional modalities. The origins of narrative therapy are drawn from post-structural theories developed by Michael White and David Epston (White & Epston, Citation1990). The post-structural approach is based on the idea that people have many interactions which shape their understanding of who they are. Based on this approach, the issues raised in therapy are not limited to clients but are influenced and formed by cultural discourses about identity and power (Madigan, Citation2011). In narrative therapy, there is a strong emphasis on separating individuals from problems so that they can externalize rather than internalize them and focus on their own self-help resources. The therapist helps children co-author a new story about themselves, in which they become heroes in their stories, learn how to solve problems, and discover strengths not noticed before. Narrative therapy also provides preschool children with opportunities for social interactions, communication, and empathy, helps them to experience and express emotions, and comprehend the feelings of others (Berkowitz, Citation2011; Koivula et al., Citation2020; Pekdogan, Citation2016; Russo, Vernam, & Wolbert, Citation2006; Wright, Diener, & Kemp, Citation2013). Telling and retelling stories offers children insight and introspection, influenced by the heroes and monsters’ challenges, enhancing a constructive and empathic attitude and minimising violence (Arora & Joshi, Citation2015; Goncalves, Voos, de Almeida, & Caromano, Citation2017). Narrative therapy has been shown to reduce anxiety and stress, bringing joy, happiness, trust, and relaxation (Arora & Joshi, Citation2015; Dousti et al., Citation2017; Goncalves et al., Citation2017; Goodman & Dent, Citation2017; Yati, Wahyuni, & Islaeli, Citation2017).

Studies on the effectiveness of narrative therapy mainly focused on hospitalized children coping with anxiety, fear, and worry (e.g. Brockington et al., Citation2021; Hudson, Leeper, Strickland, & Jessee, Citation1987; Yati et al., Citation2017). For example, Yati et al. (Citation2017) evaluated the impact of narrative therapy in play therapy on anxiety levels in preschool children during hospitalization and found that narrative therapy effectively reduces anxiety in play therapy. So far, however, there has been little discussion about the effectiveness of narrative therapy on separation anxiety symptoms in early childhood. For example, Dousti et al. (Citation2017) used two methods, storytelling and play therapy, to reduce preschool children’s separation anxiety. Their results confirmed that both methods were effective, but there was no significant difference between the storytelling and play therapy methods.

The current study

The present study examines the effectiveness of CCGPT and narrative therapy on SAD and the social-emotional behaviours of preschool children. We also investigate the efficacy of a combination of CCGPT and narrative therapy, i.e. ‘combined group’ intervention, in order to gain more insight into the effectiveness. Consequently, our research questions are: (1) Whether CCGPT, narrative therapy, or combined group interventions significantly reduce SAD in preschool children; (2) Whether CCGPT, narrative therapy, or combined group interventions promote prosocial behaviour and minimise behavioural problems in children with SAD. All three interventions were assumed to be associated with lower separation anxiety levels, higher prosocial behaviours, and lower behaviour problems in children. Our overall assumption was that children in the combined group intervention would benefit more from the intervention than the other groups.

Method

Participants

A total sample of 53 children (2.5-4-year-olds) who met the criteria for SAD, using the structured clinical interview based on DSM-5, was recruited from two psychological centres in Tehran. Parental consent was requested and received for 48 children (MAGE = 41.57 months at pre-test; 56.25% girls), who had not been involved in any form of intervention for SAD. All the participating children in the sample came from nuclear families. Children were randomly assigned into four study groups of 12 children: 1) the CCGPT group; 2) the narrative therapy group; 3) the combined group therapy; 4) the waiting control group (which also received intervention/therapy after the study).

Procedure

This study includes three intervention programmes using easy-to-apply elements comprising components mainly meant to reduce separation anxiety disorder and promote children’s social-emotional competence, which can be integrated into everyday preschool practices. Each intervention group was designed to follow a 60-minute-long session in an eight-week schedule, one session per week. The sessions were held by qualified child psychotherapists. The techniques in each intervention session were selected based on three main criteria: 1) matching children’s developmental characteristics and age; 2) including a variety of play and storytelling approaches; 3) presenting techniques that are fun, inexpensive, and easy to implement. The first 15 min of each session focused on reviewing laws covering matters of the intervention sessions, regularity, and privacy, for children. The first session in all the interventions concentrated on establishing a relationship with the therapist and other children and introducing different emotions to the children. In the beginning, the children engaged in group play activities in order to get to know the therapist and the other children in the group.

CCGPT intervention was supported by the child-centered play therapy treatment manual (Ray, Citation2011) and the guidelines of Sweeney, Baggerly, and Ray (Citation2014; see also Swan et al., Citation2019). The intervention included activities adopted from the play therapy techniques compiled by Kaduson and Schaefer (Citation1998). The play therapy room was equipped with various toys to help the children express their emotions. During the intervention, the therapist focused on facilitating children’s social and emotional competencies (such as recognizing and expressing their own emotions, acquiring a sense of responsibility, identifying others’ feelings, communication and peer relationship skills, personal and group cooperation skills), and ultimately reducing separation anxiety symptoms in children. Narrative therapy intervention focuses on helping children to view a problem from different perspectives, not to feel defined by a challenging situation, and to increase confidence in dealing with problems, improve their coping skills and resilience, understand self-identity, and value their abilities. Narrative therapy intervention included some activities adopted from ‘Our Emotions and Behaviour series’, ‘Everyday Feelings Series’ (Graves, Citation2011), and ‘Caillou Series’ (Johnson & Sevigny, Citation2003). During the intervention, the therapist engaged children in mapping out the problem (e.g. SAD) and all its aspects (e.g. when the separation anxiety symptoms occur and its effects on the body). Using different stories, the therapist tried to separate the problem from individuals and add their strengths to enhance children’s attachment security, self-concept, and understanding. The therapist involved the children in creating their own stories (real or imaginary) to relate to their situations and acted as a guide for the children, encouraging them to look for new solutions and perspectives. The combined group intervention combined games and stories used in the CCGPT and narrative therapy interventions.

Measures

The Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale. Separation anxiety symptoms were measured by the parents before and after the intervention using the Persian version of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS)-Parent Edition (Spence, Rapee, McDonald, & Ingram, Citation2001) on a 4-point scale (1 = not true at all; 4 = very often true). One subscale – measuring separation anxiety (five items) – was utilized to measure separation anxiety symptoms among children. Cronbach’s alpha for the total score was 0.92.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Children’s social-emotional behaviours were measured by parents before and after the intervention, using the Persian version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, Citation1997) on a three-point rating scale (1 = does not apply, 2 = applies partly, 3 = certainly applies). The SDQ consists of 25 items and five subscales, each containing five items: emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behaviours. Mean scores were then calculated for the subscales before and after the intervention. The SDQ total difficulties were also calculated based on subscales of emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, and peer relationship problems. The sum of the four subscales generates a total difficulties score. The Cronbach’s α of all subscales at both the pre-test and the post-test ranged from 0.74–0.87. Each subscale’s score change was then calculated in order to evaluate the interventions’ effects, i.e. subtracting the pre-test score from the post-test score. The resulting score represented the change during the evaluation period.

Data analyses

Data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical package version 25. Numerical variables were tested for normality by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and indicated non-parametric distribution. Hence, the Kruskal Wallis test was used to compare four groups, while Mann–Whitney was used to compare two groups. A P-value of ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

According to the Kruskal–Wallis test results, there was no significant difference between the intervention and control groups regarding separation anxiety symptoms and social-emotional behaviours before the intervention (see ). The results show that the groups were very similar before the intervention. However, the test showed that the prosocial behaviour subscale was slightly significant among groups before the treatment was implemented. However, the pairwise comparison showed no significant difference between the intervention groups and the control group.

Table 1. Comparing separation anxiety symptoms and SDQ subscales scores before and after the treatments for all three intervention groups.

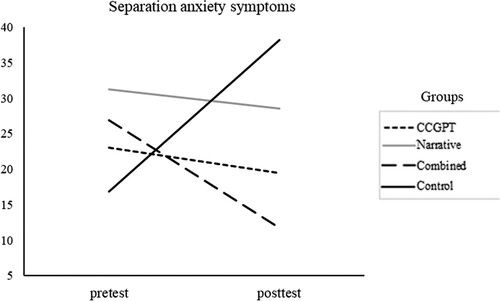

The Kruskal–Wallis test further showed a significant difference between the intervention and control groups regarding the separation anxiety subscale. Children in the CCGPT intervention group exhibited significantly lower separation anxiety symptoms (z = −3.32, p = .005) in the post-test compared to the control group. Children in the combined group intervention also showed significantly lower separation anxiety symptoms (z = −4.69, p < .000) in the post-test compared to the control group. However, the effects were not significantly different from those of the CCGPT intervention group. No difference was observed between the narrative intervention group and the control group regarding the separation anxiety subscale (see ).

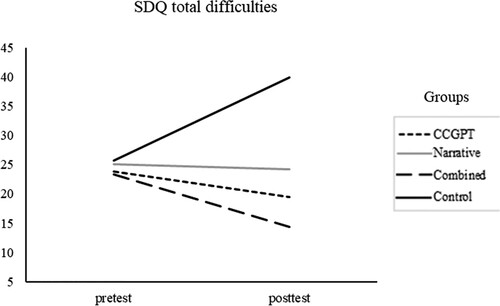

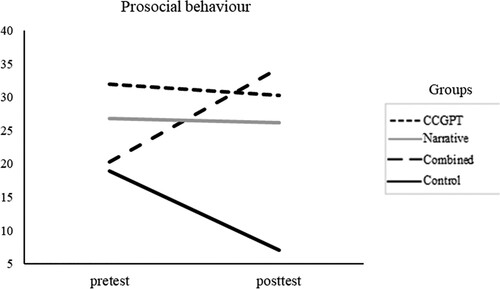

Furthermore, the Kruskal–Wallis test showed a significant difference between the intervention and control groups regarding the SDQ subscales (i.e. emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behaviours) after the treatment. Children in the combined group and CCGPT group showed significantly lower emotional problems compared to the control group (z = −4.54, p < .000; z = −3.68, p < .000, respectively), although the difference between these two treatment groups was not significant. Conduct problems showed significant decreases in post-test only for children in the combined group intervention (z = −3.25, p = .007) compared to the control group and the other intervention groups. Children in all three intervention groups also showed significantly lower peer relationship problems [z (combined group intervention) = −4.29, p < .000; z (CCGPT intervention) = −4.99, p < 0.000; z (narrative intervention) = −2.85, p = .026] at the post-test compared to the control group. Although the effect was greater for the CCGPT intervention group, the differences among the intervention groups were not significant. No difference was observed between the intervention groups and the control group regarding the hyperactivity subscale. Furthermore, children in all three intervention groups (with no significant differences among them) showed a lower level of the SDQ total difficulties (sum scores of the four problem subscales: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, and peer problems) at the post-test [z (CCGPT intervention) = −3.61, p = .002; z (narrative intervention) = −2.78, p = .034; z (combined group intervention) = −4.49, p < .000] compared to the control group (see ). Finally, all three intervention groups showed significantly higher prosocial behaviours at the post-test [z (CCGPT intervention) = 4.25, p < .000; z (narrative intervention) = 3.5, p = .003; z (combined group intervention) = 5.01, p < .000] compared to the control group. The effect was greater for the combined group intervention, but the differences among the intervention groups were not significant (see ).

Discussion

The present study explored the efficacy of CCGPT, narrative therapy intervention, and combined group intervention on separation anxiety symptoms and social-emotional behaviours of a sample of children with SAD. The results suggested that children in the CCGPT and combined group intervention groups showed lower separation anxiety symptoms after the interventions (with no significant differences) than the control group. However, children in the narrative therapy group showed no significant difference from the control group regarding separation anxiety symptoms. The results further revealed that children in all three intervention groups (with no significant differences) showed a lower level of total SDQ difficulties scores than the control group. Finally, all three intervention groups showed significantly higher prosocial behaviours than the control group after the interventions.

The first aim of this study was to examine whether the CCGPT, narrative therapy, and combined group interventions significantly reduce separation anxiety symptoms in young children with SAD. The results revealed that children in the CCGPT and combined group interventions benefited the most regarding lower separation anxiety levels. Our findings confirmed the results of previous studies on the effect of CCGPT (e.g. Dousti et al., Citation2017; Goodyear-Brown & Andersen, Citation2018; Milos & Reiss, Citation1982; Swan et al., Citation2019) and the combination of play therapy and storytelling on separation anxiety symptoms (Yati et al., Citation2017) in preschool children. CCGPT provides therapists with an opportunity to help children learn how to solve problems. Through CCGPT, children learn self-avoidance, control emotions, gain a sense of responsibility (Baggerly & Parker, Citation2005), and reveal their threatening thoughts, emotions, feelings, and experiences. Utilizing a combination of games and stories, the combined group intervention could learn effective strategies for coping with unfamiliar people and situations in the future. They could share their emotions, feelings, worries, and anxieties with peers who have the same feelings. As a result of a trustworthy environment, they were able to share their emotions and receive proper feedback from the therapist, identify themselves with the characters in the stories, and learn how to deal with challenges and interact with each other through group play (Dousti et al., Citation2017; Yati et al., Citation2017).

However, narrative therapy intervention showed no significant impact on reducing separation anxiety symptoms compared to the control group. One explanation for this finding might be that not being close to the attachment figure, young children with SAD experience extensive insecurity about the world around them, making them feel unsafe. Therefore, they may have a weaker connection with the stories and stories’ heroes. Instead of focusing on the hero’s world, they focused on the world around them and their separation from the principal attachment figure (Arora & Joshi, Citation2015; Wright et al., Citation2013).

This study’s second aim was to examine whether CCGPT, narrative therapy, and combined group interventions significantly affect early childhood social-emotional behaviours. The results showed that children in all three intervention groups showed significantly lower total SDQ difficulties than in the control group. In turn, prosocial behaviours significantly increased in all three intervention groups compared to the control group. The results were consistent with earlier findings, which showed that CCGPT is one of the best ways to reduce emotional problems and enhance social-emotional competencies in early childhood (e.g. Cheng & Ray, Citation2016; Chinekesh et al., Citation2014; Han et al., Citation2017; Swan et al., Citation2019; Swank et al., Citation2018). For example, Swank et al. (Citation2018) found that CCGPT improved preschool children’s social-emotional competencies in the intervention compared to the control group. They reported that play therapy could help children gain social competence and empathy. Further, while our study’s findings did not confirm narrative therapy’s effectiveness in reducing separation anxiety symptoms, narrative therapy positively improved children’s social and emotional behaviours. Consistently with our findings, the efficacy of narrative therapy has been demonstrated in some studies, indicating that this method could be effective in preventing or resolving behavioural problems and promoting social and emotional competencies in children (Arora & Joshi, Citation2015; Berkowitz, Citation2011; Goncalves et al., Citation2017; Pekdogan, Citation2016; Russo et al., Citation2006; Wright et al., Citation2013). It has been demonstrated that it can offer a calming experience in which using the vocabulary of play and story can help children express their thoughts and feelings with peers. Children learn social skills and self-regulatory abilities through the cycle of communicating with other group members. Since CCGPT and narrative therapy represent and encourage relationships and attitudes between group members and personal experiences and memories, children learn about the goals, values, emotions, and other’s emotions and feelings (Goodman & Dent, Citation2017; Yati et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, children learn and improve coping skills, problem-solving techniques, and different self-expression methods through interaction and involvement with other children in the group (Berkowitz, Citation2011; Sweeney et al., Citation2014).

This study has some limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results. First, the participants in this study were representative of a limited age group and were selected from a relatively small sample size, which may impact the generalization of the research findings. Future studies may address this limitation using a larger-scale replication to increase generalizability. Second, in the present study, the follow-up stage was not performed due to a lack of parental cooperation. Further follow-up, usually at one month, three months, six months, and one year later, is needed to evaluate whether successful treatment for early separation anxiety lasts.

Conclusions and implications

The present study explored the efficacy of CCGPT, narrative therapy, and a combination of CCGPT and narrative therapy (combined group) on separation anxiety symptoms and social-emotional behaviour among preschool children with SAD. The CCGPT and combined group interventions, in particular, were found to be effective psychotherapy methods for reducing separation anxiety symptoms. Furthermore, all the interventions positively impacted social-emotional behaviours in terms of higher prosocial behaviour and lower total SDQ difficulties. However, in the present study, we did not find improvements concerning separation anxiety levels in the narrative therapy intervention group compared to the control group. Consequently, our findings might have implications for designing future preventive intervention programmes. In particular, combining CCGPT and narrative therapy can be an effective psychotherapy method for reducing stress, separation anxiety symptoms, and behavioural problems and promoting prosocial behaviours in young children with SAD.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data not available due to [ethical/legal/commercial] restrictions. Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is unavailable.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maryam Zarra-Nezhad

Dr. Maryam Zarra-Nezhad, is a postdoctoral researcher in the field of psychology at the School of Applied Education Science and Teacher Education, Philosophical Faculty, University of Eastern Finland, Finland. Her research interests are early childhood social and emotional well-being, peer relations, and parenting relationships.

Fatemeh Pakdaman

Fatemeh Pakdaman from the Department of General Psychology, University of Padova, Padova, Italy, has M.A. in Clinical Psychology. Her research interests are early childhood anxiety disorders, play therapy, and narrative therapy.

Ali Moazami-Goodarzi

Dr. Ali Moazami-Goodarzi is a statistician and researcher in the field of Psychology at the Department of Psychology and Speech-Language Pathology, University of Turku, Turku, Finland. His research interests include early childhood education and learning and teachers' professional development.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author.

- Angotti, G. L., Hamilton, J. C., & Kouchi, K. A. (2022). Factitious disorder in children and adolescents. In G. Asmundson (Ed.), Comprehensive clinical psychology (2nd ed., pp. 529–546). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Arnold, D. H., Kupersmidt, J. B., Voegler-Lee, M. E., & Marshall, N. A. (2012). The association between preschool children’s social functioning and their emergent academic skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27, 376–386. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.12.009

- Arora, S., & Joshi, U. (2015). Effectiveness of life skill training through the art of narrative therapy on academic performance of children with attention deficit hyperactivity and conduct disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Nursing, 4, 9–12. doi:10.21088/jpn.2277.9035.4115.1

- Axline, V. (1969). Play therapy (Vol. 125). New York: Ballantine.

- Baggerly, J., & Parker, M. (2005). Child-centered group play therapy with African American boys at the elementary school level. Journal of Counseling & Development, 83, 387–396. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00360.x

- Berkowitz, D. (2011). Oral narrative therapy building community through dialogue, engagement, and problem solving. Young Children, 66, 36–40.

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Separation, anxiety and anger (Vol. 2). New York: Basic.

- Brand, S., Wilhelm, F. H., Kossowsky, J., Holsboer-Trachsler, E., & Schneider, S. (2011). Children suffering from separation anxiety disorders (SAD) show increased HPA axis activity compared to healthy controls. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45, 452–459. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.08.014

- Brewer, S., & Sarvet, B. (2011). Management of anxiety disorders in the pediatric primary care setting. Pediatric Annals, 40, 541–547. doi:10.3928/00904481-20111007-04

- Brockington, G., Moreira, A. P. G., Buso, M. S., da Silva, S. G., Altszyler, E., Fischer, R., & Moll, J. (2021). Storytelling increases oxytocin and positive emotions and decreases cortisol and pain in hospitalized children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118, e2018409118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2018409118

- Caputi, M., Lecce, S., Pagnin, A., & Banerjee, R. (2012). Longitudinal effects of theory of mind on later peer relations: The role of prosocial behaviour. Developmental Psychology, 48, 257–270. doi:10.1037/a0025402

- Cheng, Y. J., & Ray, D. C. (2016). Child-centered group play therapy: Impact on social-emotional assets of kindergarten children. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 41, 209–237. doi:10.1080/01933922.2016.1197350

- Chinekesh, A., Kamalian, M., Eltemasi, M., Chinekesh, S., & Alavi, M. (2014). The effect of group play therapy on social-emotional skills in preschool children. Global Journal of Health Science, 6, 163–167. doi:10.5539/gjhs.v6n2p163

- Copeland, W. E., Angold, A., Shanahan, L., & Costello, E. J. (2014). Longitudinal patterns of anxiety from childhood to adulthood: The great smoky mountains study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53, 21–33. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.017

- Dabkowska, M., Araszkiewicz, A., Dabkowska, A., & Wilkosc, M. (2011). Separation anxiety in children and adolescents. In S. Selek (Ed.), Different views of anxiety disorders (pp. 313–338). London: IntechOpen.

- Dabkowska, M. M. (2012). Separation anxiety in children as the most common disorder co-occurring with school refusal. Medical and Biological Sciences, 26(3), 5–10. doi:10.2478/v10251-012-0048-0

- Dousti, A., Pouyamanesh, J., Aghdam, F., h, G., & Jafari, A. (2017). The comparison between effectiveness of storytelling and play therapy on kindergarten children separation anxiety. International Journal of Applied Behavioural Sciences, 4(3), 28–36. doi:10.22037/ijabs.v4i3.21615

- Ehrenreich, J. T., Santucci, L. C., & Weiner, C. L. (2008). Separation anxiety disorder in youth: Phenomenology, assessment, and treatment. Psicologia Conductual, 16(3), 389–412. doi:10.1901/jaba.2008.16-389

- Feriante, J., & Bernstein, B. (2021). Separation Anxiety. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560793/

- Goncalves, L. L., Voos, M. C., de Almeida, M. H. M., & Caromano, F. A. (2017). Massage and narrative therapy reduce aggression and improve academic performance in children attending elementary school. Occupational Therapy International, 2017(5078145), 1–7.

- Goodman, G., & Dent, V. F. (2017). Studying the effectiveness of the narrative therapy/story-acting (STSA) play intervention on Ugandan preschoolers’ emergent literacy, oral language, and theory of mind in two rural Ugandan community libraries. In R. L. Steen (Ed.), Emerging research in play therapy, child counseling, and consultation (pp. 182–213). Hershey: IGI Global.

- Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581–586. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

- Goodyear-Brown, P., & Andersen, E. (2018). Play therapy for separation anxiety in children. In A. A. Drewes, & C. E. Schaefer (Eds.), Play-based interventions for childhood anxieties, fears, and phobias (pp. 158–176). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Graves, S. (2011). Our emotions and behaviour series. Minneapolis: Free Spirit Publishing.

- Gross, J. T., Stern, J. A., Brett, B. E., & Cassidy, J. (2017). The multifaceted nature of prosocial behaviour in children: Links with attachment theory and research. Social Development, 26, 661–678. doi:10.1111/sode.12242

- Han, Y., Lee, Y., & Suh, J. H. (2017). Effects of a sandplay therapy program at a childcare center on children with externalizing behavioural problems. Arts in Psychotherapy, 52, 24–31. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2016.09.008

- Hudson, C. J., Leeper, J. D., Strickland, M. P., & Jessee, P. (1987). Storytelling: A measure of anxiety in hospitalized children. Children’s Health Care, 16, 118–122. doi:10.1207/s15326888chc1602_8

- Islaeli, I., Yati, M., & Fadmi, F. R. (2020). The effect of play puzzle therapy on anxiety of children on preschooler in Kota Kendari hospital. Enfermería Clínica, 30(5), 103–105. doi:10.1016/j.enfcli.2019.11.032

- Johnson, M., & Sevigny, E. (2003). Caillou series. Montréal: Chouette Publishing.

- Kaduson, H. G., & Schaefer, C. E. (1998). 101 favorite play therapy techniques. Lanham: Jason Aronson Inc.

- Koivula, M., Turja, L., & Laakso, M. L. (2020). Using the narrative therapy method to hear children’s perspectives and promote their social-emotional competence. Journal of Early Intervention, 42, 163–181. doi:10.1177/1053815119880599

- Kossowsky, J., Pfaltz, M. C., Schneider, S., Taeymans, J., Locher, C., & Gaab, J. (2013). The separation anxiety hypothesis of panic disorder revisited: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 768–781. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12070893

- Madigan, S. (2011). Narrative therapy. Washington: American Psychological Association.

- Meany-Walen, K. K., Teeling, S., Davis, A., Artley, G., & Vignovich, A. (2016). Effectiveness of a play therapy intervention on children’s externalizing and off-task behaviours. Professional School Counseling, 20, 89–101. doi:10.5330/1096-2409-20.1.89

- Milos, M. E., & Reiss, S. (1982). Effects of three play conditions on separation anxiety in young children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 50, 389–395. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.50.3.389

- Milrod, B., Markowitz, J. C., Gerber, A. J., Cyranowski, J., Altemus, M., Shapiro, T., … Glatt, C. (2014). Childhood separation anxiety and the pathogenesis and treatment of adult anxiety. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 34–43. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13060781

- Nix, R. L., Bierman, K. L., Domitrovich, C. E., & Gill, S. (2013). Promoting children’s social-emotional skills in preschool can enhance academic and behavioural functioning in kindergarten: Findings from head start REDI. Early Education and Development, 24, 1000–1019. doi:10.1080/10409289.2013.825565

- Orgilés, M., Penosa, P., Morales, A., Fernández-Martínez, I., & Espada, J. P. (2018). Maternal anxiety and separation anxiety in children aged between 3 and 6 years: The mediating role of parenting style. Journal of Developmental and Behavioural Pediatrics: JDBP, 39, 621–628. doi:10.1097/DBP.0000000000000593

- Paulus, M. (2018). The multidimensional nature of early prosocial behaviour: A motivational perspective. Current Opinion in Psychology, 20, 111–116. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.09.003

- Pekdogan, S. (2016). Investigation of the effect of story-based social skills training program on the social skill development of 5-6-year-old children. Education and Science, 41, 305–318. doi:10.15390/EB.2016.4618

- Pellis, S. M., Pellis, V. C., & Bell, H. C. (2010). The function of play in the development of the social brain. American Journal of Play, 2(3), 278–296. https://www.museumofplay.org/app/uploads/2022/01/2-3-article-function-play-development-social-brain.pdf

- Pine, D. S., & Grun, J. (1999). Childhood anxiety: Integrating developmental psychopathology and affective neuroscience. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 9, 1–12. doi:10.1089/cap.1999.9.1

- Ramsawh, H. J., Chavira, D. A., & Stein, M. B. (2010). Burden of anxiety disorders in pediatric medical settings: Prevalence, phenomenology, and a research agenda. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 164(10), 965–972. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.170

- Ray, D. (2011). Advanced play therapy: Essential conditions, knowledge, and skills for child practice. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Constable. New York: Harcourt.

- Russo, M. F., Vernam, J., & Wolbert, A. (2006). Sandplay and narrative therapy: Social constructivism and cognitive development in child counseling. Arts in Psychotherapy, 13, 229–237. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2006.02.005

- Scharfstein, L. A., & Beidel, D. C. (2015). Social skills and social acceptance in children with anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 44, 826–838. doi:10.1080/15374416.2014.895938

- Scharfstein, L., Alfano, C., Beidel, D., & Wong, N. (2011). Children with generalized anxiety disorder do not have peer problems, just fewer friends. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 42, 712–723. doi:10.1007/s10578-011-0245-2

- Spence, S. H., Rapee, R., McDonald, C., & Ingram, M. (2001). The structure of anxiety symptoms among preschoolers. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39, 1293–1316. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00098-X

- Stubbs, R. M. (2018). A review of attachment theory and internal working models as relevant to music therapy with children hospitalized for life threatening illness. Arts in Psychotherapy, 57, 72–79. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2017.10.001

- Su, S. H., & Tsai, M. H. (2016). Group play therapy with children of new immigrants in Taiwan who are exhibiting relationship difficulties. International Journal of Play Therapy, 25, 91–101. doi:10.1037/pla0000014

- Swan, K. L., Kaff, M., & Haas, S. (2019). Effectiveness of group play therapy on problematic behaviours and symptoms of anxiety of preschool children. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 44, 82–98. doi:10.1080/01933922.2019.1599478

- Swank, J., Cheung, C., & Williams, S. (2018). Play therapy and psychoeducational school-based group interventions: A comparison of treatment effectiveness. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 43, 230–249. doi:10.1080/01933922.2018.1485801

- Sweeney, D. S., Baggerly, J. N., & Ray, D. C. (2014). Group play therapy: A dynamic approach. New York: Routledge.

- Toub, T. S., Rajan, V., Golinkoff, R., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2016). Playful learning: A solution to the play versus learning dichotomy. In D. Berch, & D. Geary (Eds.), Evolutionary perspectives on education and child development (pp. 117–145). New York: Springer.

- Vaughan, J., Coddington, J. A., Ahmed, A. H., & Ertel, M. (2017). Separation anxiety disorder in school-age children: What health care providers should know. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 31, 433–440. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2016.11.003

- Wang, Z., Whiteside, S. P., Sim, L., Farah, W., Morrow, A. S., Alsawas, M., … Daraz, L. (2017). Comparative effectiveness and safety of cognitive behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy for childhood anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(11), 1049–1056. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3036

- White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York: WW Norton & Company.

- Wright, C., Diener, M. L., & Kemp, J. L. (2013). Storytelling dramas as a community building activity in an early childhood classroom. Early Childhood Education Journal, 41, 197–210. doi:10.1007/s10643-012-0544-7

- Yati, M., Wahyuni, S., & Islaeli, I. (2017). The effect of storytelling in a play therapy on anxiety level in preschool children during hospitalization in the general hospital of buton. Public Health of Indonesia, 3, 96–101. doi:10.36685/phi.v3i3.134

- Yogman, M., Garner, A., Hutchinson, J., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Baum, R., AAP COMMITTEE ON PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF CHILD AND FAMILY HEALTH, & AAP COUNCIL ON COMMUNICATIONS AND MEDIA (2018). The power of play: A pediatric role in enhancing development in young children. Pediatrics, 142(3), e20182058. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uef.fi:2443/10.1542peds.2018-2058