ABSTRACT

This study examines how parents’ mental health symptoms, emotion regulation and mindfulness relate to parent–child reminiscing conversations about past emotional events. Fifty-four children aged 8–12 years and their parents were recruited from a child psychology clinic (n = 28) and local schools (n = 26). Dyad’s reminiscing conversations were recorded, transcribed, and coded for elaboration style, emotion content and emotion closure. Child language ability and mental health symptoms were measured, as was parent mindfulness, emotion regulation and mental health symptoms. Mindfulness acting with awareness was a unique predictor of dyad emotion closure. Depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms were not directly related to elaborative reminiscing, however, moderation by clinical status revealed a negative relationship for the community children only. These findings suggest a more complex relationship at play between parent and child mental health in reminiscing within clinical populations. Implications of these findings for a growing body of reminiscing interventions are discussed.

Parent–child conversations about past emotional events, known as reminiscing, may be an especially salient context for building child emotion regulation capacity and later wellbeing (Loth, Drabick, Leibenluft, & Hulvershorn, Citation2014; Mitchell & Reese, Citation2022; Salmon & Reese, Citation2016). High quality parent–child reminiscing has been associated with developmental benefits for children, including advanced language skills, autobiographical memory, theory of mind, self-concept coherence, self-esteem, and wellbeing (Bird & Reese, Citation2006; Fivush & Nelson, Citation2006; Fivush & Vasudeva, Citation2002; Laible, Citation2011; Reese, Bird, & Tripp, Citation2007; Wareham & Salmon, Citation2006). Given the potential benefits of high-quality reminiscing, it is important to understand how parents’ own mental health is associated with individual differences in dyadic reminiscing.

There is increasing recognition that identifying mental health symptoms, is an insufficient framework to explain caregiving challenges for parents with complex early histories (i.e. ‘high-risk’ parenting) (Judd, Newman, & Komiti, Citation2018). This move is in line with contemporary transdiagnostic approaches to mental health, which view difficulties with emotion regulation as underlying many mental health diagnoses (Cludius, Mennin, & Ehring, Citation2020; Dalgleish, Black, Johnston, & Bevan, Citation2020). If parents can regulate their own negative emotions in challenging parenting interactions, they may be better able to support their child’s emotional reactions, and be less likely to respond with harsh, or disengaged parenting (Maliken & Katz, Citation2013).

The nature of parent–child emotion reminiscing calls upon the parent’s emotion regulation to sensitively co-construct meaning around complex emotional events, so that the child can in turn learn to regulate difficult emotions (Tronick & Beeghly, Citation2011). If a parent has difficulties in regulating their own emotions, they may be less able to support their child to develop a coherent narrative (Cimino et al., Citation2019; Koren-Karie, Oppenheim, & Getzler-Yosef, Citation2008), and may find attunement difficult (Franz & McKinney, Citation2018). Koren-Karie et al. (Citation2008) observed emotional reminiscing of mothers with a history of childhood sexual abuse and their children aged 4–10 years. The mother’s trauma was measured for resolution through examining attachment disruption, disorganized thought, incoherent narrative style, and dysregulation. Unresolved trauma was associated with less maternal sensitive guidance during reminiscing, exceeding the predictive value of mental health symptoms. In addition, Valentino and colleagues (Kuehn, Lawson, Speidel, & Valentino, Citation2020; Speidel, Valentino, McDonnell, Cummings, & Fondren, Citation2019; Valentino et al., Citation2015) have demonstrated that maternal child maltreatment is associated with less elaboration and less sensitive guidance during reminiscing conversations. Together these findings suggest that parent emotion regulation difficulties may be associated with differences in reminiscing, but to date no reminiscing studies have specifically measured emotion regulation as a stand-alone construct.

Mindfulness is also considered an important transdiagnostic indicator of mental health that relates to both emotion regulation and parenting and is central to many current psychological interventions (Iani, Lauriola, Chiesa, & Cafaro, Citation2019; Pepping, Davis, & Donovan, Citation2013). Mindfulness has been defined as non-judgemental acceptance of the present moment, including positive and negative emotional experiences (Kabat-Zinn, Citation2003; Tran, Glück, & Nader, Citation2013). Mindfulness is typically conceptualized as having five facets, with non-judging, non-reacting, and acting with awareness showing the strongest associations with psychological wellbeing (Medvedev et al., Citation2021).

Higher dispositional mindfulness has been associated with more mindful parenting behaviours, higher child mindfulness (Kil, Lee, Antonacci, & Grusec, Citation2022), and more sensitive interactions during infancy (Pickard, Townsend, Caputi, & Grenyer, Citation2017). Within the parent–child relationship, mindfulness may act as a buffer for parents with early relational and complex mental health difficulties; redirecting them away from rumination about the past, or worries about the future (Purser, Citation2015) and enabling more open and responsive parenting to present moment interactions with their child (Duncan, Coatsworth, & Greenberg, Citation2009; Pickard, Townsend, Caputi, & Grenyer, Citation2018). Bird et al. (Citation2021) found that parents higher in acting with awareness mindfulness were more likely to appraise their child positively and discuss their child’s positive emotions when discussing a common household conflict. Parents higher in non-judging mindfulness were more validating. Within reminiscing interactions, more mindful parents may be better able to respond sensitively to their child’s expressed emotion, although to date no studies have empirically examined associations between parent mindfulness and reminiscing.

Existing studies examining direct associations of parent mental health symptoms with reminiscing conversations show varied results. Raikes and Thompson (Citation2006) assessed maternal depression and attachment security in a low-income sample when infants were two years of age and examined longitudinal associations with the emotion content (total emotion words) a reminiscing conversation and infant emotion understanding at age three. Although maternal depression symptoms were negatively associated with emotion understanding, there was no direct association between maternal depression and emotion word use. A more recent longitudinal study by Reese, Meins, Fernyhough, and Centifanti (Citation2019) examined associations between early maternal depression symptoms, relational indicators (attachment security, maternal sensitive behaviour, and mind-mindedness) and later reminiscing in the preschool years, again within a community sample. Reminiscing conversations were coded for mother and child elaboration (use of open-ended questions, provision of new information, and confirmations). While increasing maternal depression symptoms across time were significantly associated with fewer child elaborations, this association was no longer significant after accounting for maternal sensitivity. Swetlitz, Lynch, Propper, Coffman, and Wagner (Citation2021) examined longitudinal associations between maternal depression symptoms during infancy, reminiscing at age five, and teacher-rated child mental health difficulties at age seven years in a community sample. They found that maternal depression symptoms and sensitive parenting during infancy were significantly associated with elaborative reminiscing style at age five, in the directions expected. Together these findings provide mixed support for an association between parental depression and parent–child reminiscing.

It may be that the predominant use of community samples partially obscures a relationship, as measurement may only capture variability within low range depression symptoms. Cimino et al. (Citation2019) compared mothers with no diagnoses and diagnoses of depression, anxiety, or eating disorders on reminiscing quality with their eight-year-old children. Scale based coding measured aggregates of maternal sensitive guidance, child cooperation and exploration, and the emotional coherence of the dyad’s narrative. Analyses showed mothers with any diagnosis had significantly lower scores on all three aggregates in comparison to the non-clinical cohort. Moreover, mothers with diagnoses of depression or an eating disorder also showed significantly poorer emotion matching to their children within the reminiscing conversations. Cimino et al. (Citation2019) suggest maternal mental health difficulties disrupts the dyad’s ability to make meaning in reminiscing conversations.

This research provides important understanding of how parent mental health status might shape reminiscing; yet parent–child reminiscing is a transactional process, with both partners shaping the others’ conversation style over time and uniquely contributing to child outcomes (Farrant & Reese, Citation2000; Reese, Haden, & Fivush, Citation1993). How might children’s own mental health status interact with parents to predict reminiscing, particularly as children move into pre-adolescence when rates of mental health problems markedly increase (Loth et al., Citation2014)? Suveg, Zeman, Flannery-Schroeder, and Cassano (Citation2005, Citation2008) found that parents of children with anxiety disorders were less encouraging and descriptive during reminiscing conversations compared to parents of children without anxiety. Within a predominantly community sample, Brumariu and Kerns (Citation2015) found that children with greater anxiety symptoms were less engaged in emotion discussion and had mothers that were less elaborative and more controlling during negative emotion past event discussions. It may be that parents with their own mental health difficulties are more likely to ‘shut down’ their child’s negative emotion expressions in an attempt to regulate their own or their child’s distress (Tiwari et al., Citation2008). For example, Casline, Patel, Timpano, and Jensen-Doss (Citation2021) found an indirect effect of maternal anxiety on self-reported anxiogenic parenting through distress intolerance, but only when children had higher levels of anxiety. Further research is needed to understand how parent and child mental health interact to predict reminiscing.

Research examining parent mental health and reminiscing have utilized a variety of coding approaches. Existing literature examining maternal depression and elaboration has used frequency-based coding (Reese et al., Citation2019; Swetlitz et al., Citation2021). Leyva et al. (Citation2020) compared quality/scale based and frequency-based coding of elaboration. They found that although the approaches were moderately related, scale-based coding was uniquely related to child socio-emotional outcomes; suggesting that scale-based measurement of elaboration may be a more sensitive indicator of any associations with family mental health. Raikes and Thompson (Citation2006) measured emotion words; yet more nuanced emotion socialization mechanisms may be important in middle to late childhood when children understand mixed emotions, morality based emotional reactions, and link thoughts with self-regulation of emotions (Pons, Harris, & de Rosnay, Citation2004). Measuring explanations of emotions (causes and consequences) and closure of emotion may be of particular importance (Bird & Reese, Citation2006; Koren-Karie & Oppenhiem, Citation2003; van Bergen & Salmon, Citation2010).

The current study

Using a combined community and clinical sample, the current study aims to: (1) examine associations of parent mental health symptoms (depression, anxiety, and stress) and transdiagnostic indicators (emotion regulation and mindfulness) and with both elaborative style and emotion discussion during parent–child reminiscing conversations; and (2) examine whether the clinical or community status of the child moderates a relationship between parent mental health and reminiscing.

Expanding on past literature exploring parent mental health diagnoses (Cimino et al., Citation2019; Raikes & Thompson, Citation2006; Reese et al., Citation2019; Swetlitz et al., Citation2021), we posited that transdiagnostic indicators of dispositional mindfulness and difficulties in emotion regulation would be associated with reminiscing. We predicted that higher mindfulness and lower difficulties in emotion regulation would be related to higher elaboration and emotion discussion during reminiscing conversations. Although no existing studies have examined associations between parents’ mental health and reminiscing among child clinical samples, there is evidence that both parent and child mental health symptoms are associated with less elaborative and emotion-rich reminiscing. We, therefore, predicted that the combination of parental mental health symptoms and child clinical status would be associated with less elaborative and emotion-rich reminiscing. Because the experience of internalizing symptoms is common for typically developing children, we considered moderation by cohort rather than child symptomatology. Internalizing symptoms, by definition, are directed inwards and may therefore be missed by parents and other adults in middle childhood unless they reach a level of clinically significant impact (Martin, Ford, Dyer-Friedman, Tang, & Huffman, Citation2004). We believe this would also mean any findings have more intervention relevance for clinically referred families, a qualitatively distinct group to those who might be experiencing anxiety symptoms in the general population.

Methods

Participants

The cohort included 54 children (26 girls, 28 boys) and their primary parents (46 mothers, eight fathers). Child age ranged from 8 to 12 years (M = 9.63, SD = 1.29), and parents were aged 28–57 years (n = 48, M = 41.31, SD = 5.46), including one biological grandmother acting in a parent role. Boys and girls did not differ statistically significantly in age, t(52) = 1.35, p > .05. Dyads were recruited from the waitlist at a university child mental health clinic prior to commencing treatment (n = 28) and through invitations sent home with children at community primary schools (n = 26). Inclusion criteria were: (1) the parent and child spoke English; (2) the child was aged between 8 and 12; and (3) the child did not have a severe developmental disorder which may interfere with comprehension of assessment measures or capacity to communicate with their parent. Of the 54 parent–child pairs, the majority were European Australian (94.4%). Sixteen parents had completed higher degree research training, 20 had completed bachelor level university education and the remaining 21 parents had completed high school level education, a trade or diploma. Fifty-one families had more than one child, with 33 of the sample being first born. Socio-demographic variables (ethnicity, parental education, parent and child age, family size) were compared between cohorts and no significant differences were observed. Four additional families were recruited but excluded from the current study as they did not complete the conversation tasks. In a previous study using the same samples, the community and clinical cohorts were found to be distinct regarding the child’s mental health symptoms (Russell, Bird, & Herbert, Citation2023).

Procedure and measures

Children and their parents attended a 90-minute session in a university developmental lab. The research was approved by the University of Wollongong Human Research Ethics Committee (2018/492), and the NSW Department of Education State Education Research Applications Process (SERAP;19/184120). Parents completed questionnaires in an adjacent room, whilst the child and researcher completed the language and mental health measures. The parent and child were then invited to sit together for the conversation tasks. The reminiscing topic discussed was ‘a recent time [child] was anxious, worried, or scared’, as well as a positive recent event. To reduce burden on the child, we opted to include only one negative and one positive reminiscing conversation, as dyads took part in two other conversation tasks that are beyond the scope of the current analyses: a conflict resolution task (Bird et al., Citation2021) and future event conversation tasks (Russell et al., Citation2023). We elected to focus on anxious affect for the negative event conversation, in line with our recruitment strategy and past research (Moore, Whaley, & Sigman, Citation2004). In line with previous research that has found negative emotion conversations to be more strongly associated with child outcomes (Bird & Reese, Citation2006; Laible, Citation2011; Suveg et al., Citation2008), the positive event conversation was not included in the analysis. Firstly, the dyad engaged in a conflict resolution task, followed by a debrief and a short break. Next, the reminiscing task was presented to the dyad, which was ordered (1) negative reminiscing event, (2) positive reminiscing event, (3) negative future event, (4) positive future event (Russell et al., Citation2023). This order was designed in order to allow the child to following each conversation task before beginning the next. Dyads were asked to ‘discuss the topic as you normally would, for as long as you normally would’. The researcher left the room and the dyad’s discussion was audio recorded for later transcription and coding. Each parent was offered a $20 gift voucher in appreciation and children selected a small stationary gift.

Coding

The conversations were transcribed verbatim and any identifying information was removed before coding. Any off-topic talk was not included in the coding. Coding was completed in three passes.

Emotion exploration. Conversations were coded for emotion attributions, general emotion talk, and causes and consequences of emotions. Two independent coders coded 25% of the transcripts. Cohen’s kappa was calculated for the individual emotion codes to assess for reliability. The mean Cohen’s kappa was within the appropriate range: k = 0.74 (McHugh, Citation2012). These were tallied and then summed to create an ‘emotion exploration’ variable for child and parent.

Dyad emotion closure. Closure of emotion codes was coded on a 1–9 scale for both parent and child. The closure codes were adapted from Koren-Karie and Oppenhiem (Citation2003) closure of emotion subscale from the Autobiographical Events Emotion Dialogue (AEED) coding scheme, which has been previously aggregated with other AEED codes to represent maternal sensitive guidance (Cimino et al., Citation2019; Koren-Karie, Oppenheim, & Getzler-Yosef, Citation2004). Given our specific interest in emotion closure alongside emotion discussion or exploration, only this scale was coded, rather than the full AEED scheme. Higher scores indicated higher quality emotion closure (e.g. ways to manage emotions with an emphasis on child strengths), and lower scores indicated poorer quality closures (e.g. negative emotions heightened without ending on a positive). Two independent coders coded 25% of the transcripts. We used the two-way random-effect model based on single measures and absolute agreement to calculate inter-rated reliability (Syed & Nelson, Citation2015). The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) value was 0.79, indicating good reliability (Koo & Li, Citation2016).

Parent elaboration quality. A scale-based approach was utilized for coding elaborative reminiscing quality (Leyva et al., Citation2020). Conversations were coded on a five-point scale (1 = Low elaboration, 5 = high elaboration). Low scores indicated that parents utilized more closed questions, dismissed children’s statements, and added little information. High scores indicated a parent that used mostly open-ended questions, validated their child’s contributions, and added appropriate information. Two independent coders coded 25% of the transcripts. The two-way random-effect model based on single measures and absolute agreement resulted in an ICC of 0.82.

Demographic questionnaire

Parents were asked about their family structure, age, and highest level of education. Age and ethnicity were also collected for both parents and children.

Parent mental health symptoms

The 21-item version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995) was utilized to capture the parent’s levels of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms over the previous week (Henry & Crawford, Citation2005). The items are scored on a four-point Likert scale (0 = never to 3 = almost always). The DASS-21 demonstrates strong convergent, nomological and discriminant validity within clinical (Antony, Cox, Enns, Bieling, & Swinson, Citation1998) and non-clinical samples (Lee, Citation2019). Cronbach’s alpha for the total DASS score with the current sample was 0.95, which is consistent with existing literature (Henry & Crawford, Citation2005).

Parent mindfulness

A 24-item short form measure of the original Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., Citation2008) was utilized in the current study (Tran et al., Citation2013). The FFMQ-SF (Bohlmeijer, Klooster, Fledderus, Veehof, & Baer, Citation2011) measures five facts on a five-point Likert scale; observing, describing, non-reactivity, non-judging and acting with awareness. Factor analysis has shown using the facets to be more acceptable than a single measure of mindfulness (Bohlmeijer et al., Citation2011). The FFMQ-SF demonstrates construct validity and reliability in clinical samples (Bohlmeijer et al., Citation2011). Cronbach’s alphas for the five facets ranged from 0.70 to 0.86, which is within an acceptable range (Bohlmeijer et al., Citation2011).

Parent emotion regulation

The DERS is a 41-item self-report measure of emotion regulation difficulties (Gratz & Roemer, Citation2004). The DERS measures six facets of emotion regulation: non-acceptance of emotional responses; difficulty engaging in goal-directed activity; impulse control difficulties; lack of emotional awareness; limited access to emotion regulation strategies; and lack of emotional clarity. Responses are measured on a five-point scale (1 = almost never, 5 = almost always). High scores indicate greater difficulties in emotion regulation. Construct validity was demonstrated by Gratz and Roemer (Citation2004), with support for the categorical approach rather than an overall score. Cronbach’s alpha ranges from 0.79 to 0.91, which is within the acceptable range (Gratz & Roemer, Citation2004).

Child mental health symptoms

The RCADS is a 47-item measure of anxiety and depression symptoms for 6- to 18-year-olds, with a youth self-report (RCADS-C) and a parent report (RCADS-P) version (Chorpita, Moffitt, & Gray, Citation2005). Items are scored on a four-point scale (0 = never to 3 = always). Higher scores indicate higher anxiety and depression symptoms. Six subscales as well as overall and internalizing scores are produced. The RCADS has demonstrated good reliability and internal consistency (Piqueras, Martín-Vivar, Sandin, San Luis, & Pineda, Citation2017). In the current study, parent report total internalizing symptoms were utilized, and provided a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92.

Child language ability

To measure children’s receptive language ability, the PPVT-4 was utilized (Dunn & Dunn, Citation2007). The PPVT-4 is validated for ages 2 ½ years through 90 years (Dunn & Dunn, Citation2007). Test items are presented as four images, and the individual is asked to select the image that matches the spoken word by pointing. The PPVT-4 has been used as a measure of receptive language and covariate within other reminiscing research (e.g. Bird & Reese, Citation2006; Jack, MacDonald, Reese, & Hayne, Citation2009; Taumoepeau & Reese, Citation2013).

Analysis plan

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS v.25), version 25. A priori power calculations using G*Power determined n = 52 as an appropriate sample size with an effect size = 0.2, and power = .80 for the regression. Moderation was tested post hoc to overall study design. A sensitivity power analysis was conducted with a sample size of 54 and 80% power (α = .05, two-tailed), which indicated the analysis would be sensitive to effects of t(49) = 2.01, f2 = 0.15. This means the study would not be able to reliably detect an effect smaller than f2 = 0.15. Across the survey data 1.8% of the questionnaire data was missing at random (Littles MCAR p = 1.0). Expectation maximization was used in these cases to impute the missing data. There was no more than one instance of missing data from any scale.

Analyses were first conducted for descriptive statistics. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), independent sample t-tests and Pearson correlation coefficients were conducted to examine potential covariates. Associations between reminiscing variables and parent depression, anxiety, stress, emotion dysregulation and mindfulness were examined using correlation, and then regression analyses. Note, these analyses were run with the sample as a whole and then repeated with mothers only (to ensure that inclusion fathers and the grandparent did not change results). A similar pattern of findings emerged so the analyses presented are for the sample as a whole. Finally, Hayes (Citation2009) PROCESS macro was used to test whether associations of parent mental health with reminiscing was moderated by child clinical or community status. We previously confirmed statistically significant differences between the two cohorts in a separate study, which utilized the same sample but focused on future cognitions (Russell et al., Citation2023). PROCESS uses bias-corrected bootstrapping, an approach which maximizes power with small samples and is robust to violations of normality.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics of reminiscing variables (parent and child emotion exploration, dyad emotion closure, and parent elaboration quality) and mental health indicators are presented in . ANOVA assessed for potential covariates of parent education level and child grade and found no differences between groups on reminiscing variables. T-tests revealed no differences in reminiscing variables and demographic factors (i.e. parent or child sex, number of children (only child vs multi-child family), child birth order, and ethnicity).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for parent-child reminiscing conversation.

Correlations were conducted for continuous variables of child age, parent age, and child language ability. For parent and child age, there were no significant correlations. However, children’s language ability as measured on the PPVT-4 was significantly correlated with emotion closure (n = 54, r = .301, p = .027) and as such was included in subsequent analyses as a covariate.

Main analyses

Parent mental health indicators

To test the relationship between reminiscing style and parent mental health indicators, correlation analyses were conducted (see ). Mental health symptoms, as measured by the DASS-21, showed no significant correlations with any reminiscing variables. Maternal elaboration, and child and parent emotion exploration were not significantly correlated with any mental health indicators. Two transdiagnostic indicators were correlated at a statistically significant level (p < .05) with emotion closure: FFMQ acting with awareness (r = 0.351, p = .009), and DERS impulse control (r = −0.273, p = .046).

Table 2. Pearson’s r correlations with reminiscing variables (n = 54).

Regression model

To examine mental health correlates and reminiscing, a hierarchical regression model was tested. Firstly, assumptions were evaluated; observation of plots indicated no univariate outliers. Variables fell within the acceptable range of +/− 2 for skewness and kurtosis (George & Mallery, Citation2010). Plots indicated normality, linearity and homoscedasticity of residuals could be assumed. Variance Inflation Factor and Tolerance were within acceptable ranges, which indicated that multicollinearity was not of concern ().

Table 3. Hierarchical multiple regression predicting emotion closure quality.

In step 1 the PPVT-4 was included as a covariate and accounted for 9% of the variance (R2 = .09, F (1, 52) = 5.169, p = .027). At step 2, acting with awareness was added to the model, and accounted for an additional 9.3% of the variance, which was significant (ΔR2 = .093, F (1, 51) = 5.822, p = .019). At step 3, DERS impulse control was added, which did not significantly contribute to the model (ΔR2 = .016, F (1, 50) = 1.030, p = .315). In combination, the three predictor variables explained 20% of the variance in emotion closure quality (R2 = .200, adjusted R2 = .152, F (1, 50) = 4.169, p = .01).

Moderation by cohort

To assess if child clinical status moderated the relationship between parent mental health and reminiscing, a series of moderation analyses were conducted using Hayes (Citation2009) PROCESS macro. Child cohort (clinical or community) was the moderator, the four reminiscing variables were the dependent variables, the DASS-21 scores were the independent variables, and children’s language ability (PPVT-4) was included in all models as a covariate. Results are displayed in .

Table 4. Moderation of mental health indicators (X) to reminiscing (Y) by cohort.

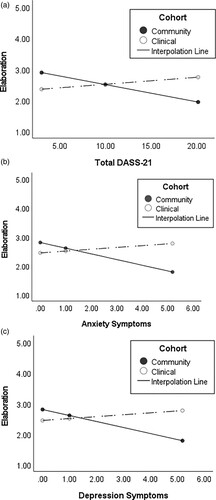

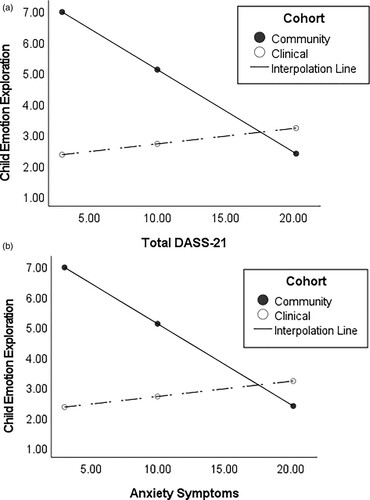

The total DASS-21 and elaboration relationship was significantly moderated by child cohort. The interaction effect showed that the community (but not clinical) sample had lower elaboration when the parent had higher DASS-21 scores ((A)). The same pattern was observed for elaboration with parent anxiety ((B)), and depression ((C)). A similar pattern emerged for child emotional exploration and total DASS-21. Again, the community (but not clinical) cohort showed lower child emotional expression when the parent had higher DASS-21 scores ((A)) and parent anxiety ((B)).

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to broaden understanding of the relationship between parent–child reminiscing and multiple indicators of parent mental health. Our findings indicate parent dispositional mindfulness (in the form of acting with awareness) and emotion dysregulation (in the form of impulse control difficulties) were correlated with parent–child dyad emotion closure in the directions expected. Regression analysis indicated that only acting with awareness had a unique association with dyad emotion closure. We did not observe a direct relationship between parent mental health symptoms (depression, anxiety, and stress) and reminiscing. However, when exploring moderation by clinical status of the child, a significant interaction was observed. Dyads from the community showed the expected relationship in line with previous literature (Swetlitz et al., Citation2021), whereby greater parent depression symptoms were associated with less elaborative and emotion-rich reminiscing. Within the clinical cohort, however, no significant relationship was observed. Overall, these findings provide the first empirical support for an association between parents’ dispositional mindfulness and emotion reminiscing and suggest that the relationship between parental depression symptoms and emotion reminiscing may depend on the child’s own mental health status.

We measured multiple indicators of parent mental health, including mindfulness facets and emotion regulation difficulties. Parent’s acting with awareness was found to be a unique predictor of dyad emotion closure when reminiscing about past negative events. This finding suggests that a parent’s capacity to be mindfully present may enable discussions that lead to higher quality closure of negative emotions. Why might this be? Acting with awareness is central to the concept of present moment awareness, which is integral to most mindfulness-based psychological interventions (Kabat-Zinn, Citation2003). Of all mindfulness components, acting with awareness has been shown to have the strongest associations with prevention of psychopathology (Cortazar & Calvete, Citation2019). Within the developmental literature, parent acting with awareness has also been shown to be a strong predictor of fewer parent–child relationship problems and may be closely related to maternal sensitivity (Boekhorst et al., Citation2020), which has been associated with high quality reminiscing (Reese et al., Citation2019; Swetlitz et al., Citation2021). Perhaps acting with awareness enables a parent to put aside their own reactions and experiences, better enabling the dyad to move towards closure of the emotion. It is interesting to note that we did not find an association of acting with awareness, or any other mindfulness facet, with elaboration or emotion exploration; suggesting acting with awareness may specifically promote emotion closure. Past research also found acting with awareness to be associated with enhanced conflict closure through greater use of positive emotion words (Bird et al., Citation2021). Together these findings suggest that mindful acting with awareness may enable parents to support children towards more positive closure of difficult situations – both located in the past (reminiscing) and ongoing (conflict resolution).

Parent depression, anxiety and stress symptoms were not significantly correlated with any of the measured reminiscing variables across the total sample. The mixed findings of past research within varying community or clinical cohorts (Cimino et al., Citation2019; Raikes & Thompson, Citation2006; Reese et al., Citation2019; Swetlitz et al., Citation2021) indicated further exploration of this relationship was needed. Moderation analyses demonstrated a relationship between parent mental health symptoms and reminiscing (elaboration and child emotion exploration) within the community but not the clinical cohort. Specifically, we found that elaboration quality was negatively associated with parent depression, anxiety, and total DASS-21 symptoms for the community cohort, although it should be noted that in this cohort parent levels of symptoms are relatively mild. This is perhaps not surprizing given we recruited half the sample based on child clinical status, not parent. These findings are in line with Swetlitz et al. (Citation2021) who found maternal depression symptoms were linked with elaboration in a community recruited population.

An interaction with parent mental health and child clinical status was also found for child emotion exploration. For community families only, higher parent anxiety and total DASS-21 symptoms were associated with lower child emotion exploration. Although we know of no other study that has examined the interaction between parent mental health and child clinical status in reminiscing, these findings are consistent with potential emotional avoidance when anxiety is present. Suveg et al. (Citation2005, Citation2008) found that parents of children with anxiety used fewer emotion explanations and Cimino et al. (Citation2019) found that mothers with an anxiety diagnosis had children that were less engaged and cooperative during reminiscing. It is interesting that our findings do not suggest a compounding transactional relationship whereby child clinical status and parent mental health symptoms together are associated with poorer emotion exploration and closure. Instead, parent mental health symptoms were associated with less emotion exploration and closure among the community sample only. Further investigation is needed to understand this complex relationship. One possibility is that older children take on an increasing role as regulatory partners. Perhaps children without mental health difficulties respond to parents with mental health difficulties with more avoidant coping in an attempt to regulate the parent. For clinically referred children, a more complex transactional relationship may be at play, with other unmeasured variables potentially explaining this relationship. For example, insecure attachment styles have been linked with psychopathology in children (Spruit et al., Citation2020). It may be that parent or child secure attachment may buffer any negative impacts of parent mental health symptoms on reminiscing quality, or that insecure or disorganized attachment in combination with parent mental health difficulties may predict poorer quality reminiscing. Interestingly, Lawson, Valentino, McDonnell, and Speidel (Citation2018) found that maternal attachment anxiety predicted less elaborative reminiscing, but only for dyads with non-maltreating mothers. Although we cannot draw any comparisons between maltreating mothers and children referred for anxiety, both our findings and Lawson et al. suggest that findings from community reminiscing samples cannot necessarily be applied to clinical samples. Longitudinal research with measures of attachment and both parent and child mental health and reminiscing across time will help to elucidate these relationships. Qualitative research asking both parents and children about their intentions, goals and experiences of reminiscing may also help to understand the transactional nature of these interactions (Pavlova, Mueri, Peterson, Graham, & Noel, Citation2022).

Strengths and limitations

These novel findings are the first to explore the relationship between multiple parent mental health indicators and reminiscing during middle childhood. The mixed clinical-community sample allowed for moderation analyses examining how parent mental health symptoms and child clinical status relate to reminiscing. A further strength of this study is the multi-faceted coding approach: capturing parent, child and dyadic aspects whilst also utilizing scale based and frequency-based coding. Measuring emotion exploration rather than emotion words reflects the more advanced level of emotion knowledge in middle childhood.

This study also had several limitations. The sample is not representative of the general population, being predominantly Western and well educated, as well as being mostly two-parent families (n = 42). Notably, we included parents of both genders and a grandparent. Research investigating father–child reminiscing is sparse, and some studies point to possible parent gender differences in the function of reminiscing (Aznar & Tenenbaum, Citation2015; Pavlova et al., Citation2022). Our language scores were somewhat high; however, the mean fell within one standard deviation of the mean of the normative sample. Although there is no significant different between groups and language controlled for in the study, the findings of this study may not be generalizable to children with lower language ability. This is important because children with mental health difficulties are more likely to also present with comorbid language difficulties, and language difficulties have been posed as an important intervention target for these children (Salmon, O’Kearney, Reese, & Fortune, Citation2016). We also note the lower levels of parent symptomology due to our recruitment strategy not targeting parent mental health. This should be considered in interpreting our findings, which does not extrapolate to a clinical sample of parents. We measured dispositional mindfulness and future research could consider a specific measure of mindful parenting, which may better elucidate any associations with a parenting behaviour such as reminiscing (Parent, McKee, Mahon, & Foreh, Citation2016). Dyad’s may have been biased or influenced by the conflict resolution task which preceded reminiscing, however a small break and debrief between was included in attempt to mitigate this possibility. The cross-sectional nature of this research means that we cannot conclude whether parents or children are adapting to the other’s mental health symptoms, or whether components of reminiscing style and content potentially contribute to child development of mental health difficulties, or indeed partially explain the intergenerational transmission of mental health difficulties (Swetlitz et al., Citation2021). Moreover, we recognize the moderation analyses are underpowered due to the sample size and note the need for interpreting these with caution. Despite these limitations, the study provides preliminary evidence for parent transdiagnostic indicators, as well as an avenue for future research to investigate differences in reminiscing based upon parent or child mental health.

Conclusion

Mindful acting with awareness was a unique predictor of emotion closure quality in reminiscing conversations. If, as our findings suggest, parent mindfulness is associated with higher quality reminiscing, it may be helpful for future reminiscing interventions to include a parent mindfulness component. Evidence from the behavioural parent management training literature suggests that targeting parent emotion dysregulation and mindfulness can enhance the efficacy for a large proportion of families who do not benefit from a more traditional skills-based parenting approach (Maliken & Katz, Citation2013). The current findings also suggest that parent mental health symptoms are only associated with emotion exploration and elaboration during reminiscing for community or non-clinical children. Although our community and clinical samples are small and may not be generalizable, these findings highlight a clear need to better understand the complexity of these transactional interactions as children move into middle childhood and adolescence.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the funding support by the Australian Rotary Health PhD scholarship from Josephine Margaret Redfern & Ross Edward Redfern (Rotary Club of Granville, NSW, Australia).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sophie Russell

Sophie Russell is a psychologist, and candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy in Clinical Psychology at the University of Wollongong within the Family Learning and Interaction Lab at Early Start, School of Psychology. Her research investigates intergenerational transmission of mental health through everyday family conversations and interactions. Among her recent articles are ‘Parents' Dispositional Mindfulness, Child Conflict Discussion, and Childhood Internalizing Difficulties: A Preliminary Study' (Mindfulness, 2021) and ‘Antenatal mind-mindedness and its relationship to maternal-fetal attachment in pregnant women’ (Health Care for Women International, 2021).

Amy L. Bird

Dr Amy Bird is a Senior Lecturer in Clinical Psychology at the University of Auckland. Amy has been a registered and practicing Clinical Psychologist for over 15 years, where she has worked in both public and private mental health settings. Amy's research interests focus on the intersection between developmental and clinical psychology. She has a particular focus on parent-child relationships and interactions and how parents can be supported in parenting interactions to prevent the intergenerational transmission of mental health difficulties. Amy has expertise in longitudinal research and is a co-Domain Leader (Family & Whānau) for Growing Up in New Zealand: a pre-birth cohort study following over 6,000 families who were born in 2009-2010.

Josephine McNamara

Dr Josephine McNamara is a practicing clinical psychologist and Dr of Clinical Psychology, who writes in parenting, antenatal mental health and attachment. Dr McNamara's recent articles include ‘The role of pregnancy acceptability in maternal mental health and bonding during pregnancy' (BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 2022), and ‘A systemic review of maternal wellbeing and its relationship with maternal fetal attachment and early postpartum bonding’ (PLoS ONE, 2019).

Jane S. Herbert

Jane Herbert an associate professor in the School of Psychology, Faculty of the Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities, at the University of Wollongong writes on early cognition, parent child-interaction, and parental well-being from pregnancy onwards. Among her recent articles are ‘Mindful Parent Training for Parents of Children Aged 3–12 Years with Behavioural Problems: A Scoping Review’ (Mindfulness, 2022) and ‘The role of pregnancy acceptability in maternal mental health and bonding during pregnancy’ (BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 2022).

References

- Antony, M. M., Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., Bieling, P. J., & Swinson, R. P. (1998). Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment, 10(2), 176–181. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176

- Aznar, A., & Tenenbaum, H. R. (2015). Gender and age differences in parent-child emotion talk. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 33(1), 148–155. doi:10.1111/bjdp.12069

- Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., … Williams, G. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. doi:10.1177/1073191107313003

- Bird, A. L., & Reese, E. (2006). Emotional reminiscing and the development of an autobiographical self. Developmental Psychology, 42(4), 613–626. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.613

- Bird, A. L., Russell, S., Pickard, J. A., Donovan, M., Madsen, M., & Herbert, J. S. (2021). Parents’ dispositional mindfulness, child conflict discussion, and childhood internalizing difficulties: A preliminary study. Mindfulness, doi:10.1007/s12671-021-01625-5

- Boekhorst, M. G. B. M., Potharst, E. S., Beerthuizen, A., Hulsbosch, L. P., Bergink, V., Pop, V. J. M., & Nyklíček, I. (2020). Mindfulness during pregnancy and parental stress in mothers raising toddlers. Mindfulness, 11(7), 1747–1761. doi:10.1007/s12671-020-01392-9

- Bohlmeijer, E., Klooster, P. M., Fledderus, M., Veehof, M., & Baer, R. (2011). Psychometric properties of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in depressed adults and development of a short form. Assessment, 18(3), 308–320. doi:10.1177/1073191111408231

- Brumariu, L. E., & Kerns, K. A. (2015). Mother-child emotion communication and childhood anxiety symptoms. Cognition and Emotion, 29(3), 416–431. doi:10.1080/02699931.2014.917070

- Casline, E., Patel, Z. S., Timpano, K. R., & Jensen-Doss, A. (2021). Exploring the link between transdiagnostic cognitive risk factors, anxiogenic parenting behaviors, and child anxiety. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 52(6), 1032–1043. doi:10.1007/s10578-020-01078-2

- Chorpita, B. F., Moffitt, C. E., & Gray, J. (2005). Psychometric properties of the revised child anxiety and depression scale in a clinical sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43, 309–322. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.004

- Cimino, S., Cerniglia, L., Tambelli, R., Ballarotto, G., Erriu, M., Paciello, M., … Koren-Karie, N. (2019). Dialogues about emotional events between mothers with anxiety, depression, anorexia nervosa, and no diagnosis and their children. Parenting, 5192, 1–14. doi:10.1080/15295192.2019.1642688

- Cludius, B., Mennin, D., & Ehring, T. (2020). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic process. Emotion, 20(1), 37–42. doi:10.1037/emo0000646

- Cortazar, N., & Calvete, E. (2019). Dispositional mindfulness and its moderating role in the predictive association between stressors and psychological symptoms in adolescents. Mindfulness, 10(10), 2046–2059. doi:10.1007/s12671-019-01175-x

- Dalgleish, T., Black, M., Johnston, D., & Bevan, A. (2020). Transdiagnostic approaches to mental health problems: Current status and future directions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(3), 179–195. doi:10.1037/ccp0000482

- Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent-child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(3), 255–270. doi:10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3

- Dunn, L., & Dunn, D. M. (2007). PPVT-4: Peabody picture vocabulary test. Washington, DC: Pearson Assessments. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/t15144-000

- Farrant, K., & Reese, E. (2000). Maternal style and children’s participation in reminiscing: Stepping stones in children’s autobiographical memory development. Journal of Cognition and Development, 1(2), 193–225. doi:10.1207/S15327647JCD010203

- Fivush, R., & Nelson, K. (2006). Parent-child reminiscing locates the self in the past. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 24(1), 235–251. doi:10.1348/026151005X57747

- Fivush, R., & Vasudeva, A. (2002). Remembering to relate: Socioemotional correlates of mother-child reminiscing. Journal of Cognition and Development, 3(1), 73–90. doi:10.1207/S15327647JCD0301_5

- Franz, A. O., & McKinney, C. (2018). Parental and child psychopathology: Moderated mediation by gender and parent–child relationship quality. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 49(6), 843–852. doi:10.1007/s10578-018-0801-0

- George, D., & Mallery, M. (2010). SPSS for windows step by step: A simple guide and reference (10th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. doi:10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

- Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. doi:10.1080/03637750903310360

- Henry, J., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(2), 227–239. doi:10.1348/014466505X29657

- Iani, L., Lauriola, M., Chiesa, A., & Cafaro, V. (2019). Associations between mindfulness and emotion regulation: The key role of describing and nonreactivity. Mindfulness, 10(2), 366–375. doi:10.1007/s12671-018-0981-5

- Jack, F., MacDonald, S., Reese, E., & Hayne, H. (2009). Maternal reminiscing style during early childhood predicts the age of adolescents’ earliest memories. Child Development, 80(2), 496–505. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01274.x

- Judd, F., Newman, L. K., & Komiti, A. A. (2018). Time for a new zeitgeist in perinatal mental health. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(2), 112–116. doi:10.1177/0004867417741553

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bpg016

- Kil, H., Lee, E., Antonacci, R., & Grusec, J. E. (2022). Mindful parents, mindful children? Exploring the Role of Mindful Parenting. Parenting, 00, 1–19. doi:10.1080/15295192.2022.2049601

- Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. doi:10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

- Koren-Karie, N., Oppenheim, D., & Getzler-Yosef, R. (2004). Mothers who were severely abused during childhood and their children talk about emotions: Co-construction of narratives in light of maternal trauma. Infant Mental Health Journal, 25(4), 300–317. doi:10.1002/imhj.20007

- Koren-Karie, N., Oppenheim, D., & Getzler-Yosef, R. (2008). Shaping children’s internal working models through mother-child dialogues: The importance of resolving past maternal trauma. Attachment and Human Development, 10(4), 465–483. doi:10.1080/14616730802461482

- Koren-Karie, N., & Oppenhiem, D. (2003). Autobiographical Emotional Events Dialogues : Coding Manual (Unpublished Manual).

- Kuehn, M., Lawson, M., Speidel, R., & Valentino, K. (2020). The association between maternal reminiscing and maternal perpetration of neglect. Child Maltreatment, 25(4), 468–477. doi:10.1177/1077559520916241

- Laible, D. (2011). Does it matter if preschool children and mothers discuss positive vs. Negative events during reminiscing? Links with mother-reported attachment, family emotional climate, and socioemotional development. Social Development, 20(2), 394–411. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2010.00584.x

- Lawson, M., Valentino, K., McDonnell, C. G., & Speidel, R. (2018). Maternal attachment is differentially associated with mother–child reminiscing among maltreating and nonmaltreating families. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 169. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2017.12.005

- Lee, D. (2019). The convergent, discriminant, and nomological validity of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21). Journal of Affective Disorders, 259(January), 136–142. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.036

- Leyva, D., Reese, E., Laible, D., Schaughency, E., Das, S., & Clifford, A. (2020). Measuring parents’ elaborative reminiscing: Differential links of parents’ elaboration to children’s autobiographical memory and socioemotional skills. Journal of Cognition and Development, 21(1), 23–45. doi:10.1080/15248372.2019.1668395

- Loth, A. K., Drabick, D. A. G., Leibenluft, E., & Hulvershorn, L. A. (2014). Do childhood externalizing disorders predict adult depression? A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(7), 1103–1113. doi:10.1007/s10802-014-9867-8.Do

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

- Maliken, A. C., & Katz, L. F. (2013). Exploring the impact of parental psychopathology and emotion regulation on evidence-based parenting interventions: A transdiagnostic approach to improving treatment effectiveness. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16(2), 173–186. doi:10.1007/s10567-013-0132-4

- Martin, J., Ford, C., Dyer-Friedman, J., Tang, J., & Huffman, L. (2004). Patterns of agreement between parent and child ratings of emotional and behavioral problems in an outpatient clinical setting: When children endorse more problems. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 25(3), 150–155. doi:10.1097/00004703-200406000-00002

- Mchugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. https://doi.org/10.11613/bm.2012.031

- Medvedev, O. N., Cervin, M., Barcaccia, B., Siegert, R. J., Roemer, A., & Krägeloh, C. U. (2021). Network analysis of mindfulness facets, affect, compassion, and distress. Mindfulness, 12(4), 911–922. doi:10.1007/s12671-020-01555-8

- Mitchell, C., & Reese, E. (2022). Growing memories: Coaching mothers in elaborative reminiscing with toddlers benefits adolescents’ turning-point narratives and wellbeing. Journal of Personality, doi:10.1111/jopy.12703

- Moore, P. S., Whaley, S. E., & Sigman, M. (2004). Interactions between mothers and children: Impacts of maternal and child anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113(3), 471. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.471

- Parent, J., McKee, L. G., Mahon, J., & Foreh, R. (2016). The association of parent mindfulness with parenting and youth psychopathology across three developmental stages. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1), 191–202. doi:10.1007/s10802-015-9978-x

- Pavlova, M., Mueri, K., Peterson, C., Graham, S. A., & Noel, M. (2022). Mother– and father–child reminiscing about past events involving pain, fear, and sadness: Observational cohort study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 1–10. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsac012

- Pepping, C. A., Davis, P. J., & Donovan, A. O. (2013). Individual differences in attachment and dispositional mindfulness: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(3), 453–456. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.10.006

- Pickard, J. A., Townsend, M., Caputi, P., & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2017). Observing the influence of mindfulness and attachment styles through mother and infant interaction: A longitudinal study. Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(3), 343–350. doi:10.1002/imhj.21645

- Pickard, J. A., Townsend, M. L., Caputi, P., & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2018). Top-down and bottom-up: The role of social information processing and mindfulness as predictors in maternal–infant interaction. Infant Mental Health Journal, 39(1), 44–54. doi:10.1002/imhj.21687

- Piqueras, J. A., Martín-Vivar, M., Sandin, B., San Luis, C., & Pineda, D. (2017). The revised child anxiety and depression scale: A systematic review and reliability generalization meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 218(December 2016), 153–169. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.022

- Pons, F., Harris, P. L., & de Rosnay, M. (2004). Emotion comprehension between 3 and 11 years: Developmental periods and hierarchical organization. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 1(2), 127–152. doi:10.1080/17405620344000022

- Purser, R. (2015). The myth of the present moment. Mindfulness, 6(3), 680–686. doi:10.1007/s12671-014-0333-z

- Raikes, H. A., & Thompson, R. A. (2006). Family emotional climate, attachment security and young children’s emotion knowledge in a high risk sample. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 24(1), 89–104. doi:10.1348/026151005X70427

- Reese, E., Bird, A. L., & Tripp, G. (2007). Children’s self-esteem and moral self: Links to parent-child conversations regarding emotion. Social Development, 16(3), 460–478. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00393.x

- Reese, E., Haden, C. A., & Fivush, R. (1993). Mother-child conversations about the past: Relationships of style and memory over time. Cognitive Development, 8, 403–430. doi:10.1016/s0885-2014(05)80002-4

- Reese, E., Meins, E., Fernyhough, C., & Centifanti, L. (2019). Origins of mother-child reminiscing style. Development and Psychopathology, 31, 2. doi:10.1017/S0954579418000172

- Russell, S., Bird, A. L., & Herbert, J. S. (2023). A clinical-community comparison of parent-child emotion conversations about the past and the anticipated future [Manuscript submitted for publication]. School of Psychology, University of Wollongong.

- Salmon, K., O’Kearney, R., Reese, E., & Fortune, C. (2016). The role of language skill in child psychopathology: Implications for intervention in the early years. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19(4), 352–367. doi:10.1007/s10567-016-0214-1

- Salmon, K., & Reese, E. (2016). The benefits of reminiscing with young children. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(4), 233–238. doi:10.1177/0963721416655100

- Speidel, R., Valentino, K., McDonnell, C. G., Cummings, E. M., & Fondren, K. (2019). Maternal sensitive guidance during reminiscing in the context of child maltreatment: Implications for child self-regulatory processes. Developmental Psychology, 55(1), 110–122. doi:10.1037/dev0000623

- Spruit, A., Goos, L., Weenink, N., Rodenburg, R., Niemeyer, H., Stams, G. J., & Colonnesi, C. (2020). The relation between attachment and depression in children and adolescents: A multilevel meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(1), 54–69. doi:10.1007/s10567-019-00299-9

- Suveg, C., Sood, E., Barmish, A., Tiwari, S., Hudson, J. L., & Kendall, P. C. (2008). “I’d rather not talk about it”: Emotion parenting in families of children with an anxiety disorder. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(6), 875–884. doi:10.1037/a0012861

- Suveg, C., Zeman, J., Flannery-Schroeder, E., & Cassano, M. (2005). Emotion socialization in families of children with an anxiety disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(2), 145–155. doi:10.1007/s10802-005-1823-1

- Swetlitz, C., Lynch, S. F., Propper, C. B., Coffman, J. L., & Wagner, N. J. (2021). Examining maternal elaborative reminiscing as a protective factor in the intergenerational transmission of psychopathology. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 49(8), 989–999. doi:10.1007/s10802-021-00790-4

- Syed, M., & Nelson, S. C. (2015). Guidelines for establishing reliability when coding narrative data. Emerging Adulthood, 3(6), 375–387. doi:10.1177/2167696815587648

- Taumoepeau, M., & Reese, E. (2013). Maternal reminiscing, elaborative talk, and children’s theory of mind: An intervention study. First Language, 33(4), 388–410. doi:10.1177/0142723713493347

- Tiwari, S., Podell, J. C., Martin, E. D., Mychailyszyn, M. P., Furr, J. M., & Kendall, P. C. (2008). Experiential avoidance in the parenting of anxious youth: Theory, research, and future directions. Cognition & Emotion, 22(3), 480–496. doi:10.1080/02699930801886599

- Tran, U. S., Glück, T. M., & Nader, I. W. (2013). Investigating the five facet mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ): Construction of a short form and evidence of a two-factor higher order structure of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(9), 951–965. doi:10.1002/jclp.21996

- Tronick, E., & Beeghly, M. (2011). Infants’ meaning-making and the development of mental health problems. American Psychologist, 66(2), 107–119. doi:10.1037/a0021631

- Valentino, K., Hibel, L. C., Cummings, E. M., Nuttall, A. K., Comas, M., & McDonnell, C. G. (2015). Maternal elaborative reminiscing mediates the effect of child maltreatment on behavioral and physiological functioning. Development and Psychopathology, 27, 1515–1526. doi:10.1017/S0954579415000917

- van Bergen, P., & Salmon, K. (2010). Emotion-oriented reminiscing and children’s recall of a novel event. Cognition and Emotion, 24(6), 991–1007. doi:10.1080/02699930903093326

- Wareham, P., & Salmon, K. (2006). Mother-child reminiscing about everyday experiences: Implications for psychological interventions in the preschool years. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(5), 535–554. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.05.001