ABSTRACT

This study examines whether family income in early childhood is related to achievements of Israeli students in standardized tests at primary school. We analyzed data from the Israeli censuses of 1995 and 2008, which include information on family income and socio-economic background of children along with data pertaining to their achievements in standardized tests taken in fifth-grade. The findings show that belonging to the lowest quintile of family disposable income in early childhood had a negative and significant effect on future educational achievements, controlling for family income in late childhood and other socio-demographic variables. Furthermore, the effect of family income was stronger when measured at birth – age two, than at ages 3–5. These findings are consistent with the claim that child development is most sensitive to environmental influences in the very first years of life.

Introduction

The early years of life are an important developmental stage in humans. Conventional wisdom has it that investment in early childhood enhances the odds of optimal child development, higher educational achievements, and greater success in adulthood (e.g. Heckman, Citation2008, Citation2010, Citation2011). In recent years, this hypothesis has received mounting empirical support (e.g. Troller-Renfree et al., Citation2022). Researchers have found that the learning environment and access to enriching stimuli during early childhood have a major impact on the structural development of the young brain (Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar, & Heim, Citation2009; Noble et al., Citation2015; Rosenzweig, Citation2003). Additionally, poverty in early childhood is associated with elevated levels of parental stress, low levels of positive stimulation provided to the children, and a lower quality of early childhood education on average (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, Citation1997; Lipina, Citation2016). These factors are likely to mediate the adverse effects of poverty in early childhood on children’s subsequent scholastic performance. According to the First 1,000 Days theory, their effect may be especially pronounced from conception to the child's second birthday, a period in which the development of the human brain is most susceptible to environmental effects (Cunha, Leite, & Almeida, Citation2015). Based on that premise, this paper examines the link between family income during early childhood and late childhood on the one hand, and educational achievements in primary school on the other hand.

Inequality in educational achievements in Israel

Israel consistently ranks lower than other developed countries in international achievement tests, such as PISA. For example, Israel has the highest proportion of students (34%) at the lowest achievement level in mathematics, compared with the OECD average of 24% (RAMA, Citation2019). Furthermore, inequality in scholastic achievements among Israeli students has been among the highest of developed countries for decades (Blass, Citation2020; RAMA, Citation2018, Citation2019), with the largest gap between the scores of the 5th and the 95th percentiles in mathematical, reading and scientific literacy on PISA exam out of the 70 countries that participated in the test in 2018 (RAMA, Citation2019).

In recent years, it has become increasingly clear that inequalities in educational achievements develop at very young ages, even before children enter the education system (Farkas & Beron, Citation2004). Feinstein (Citation2003), for instance, found clear differences in cognitive tests among 22-month-old infants in Britain according to their socio-economic status. His most striking finding is that socio-economic gaps in cognitive performance widened over time. Thus, achievement gaps between children from diffe rent socio-economic backgrounds emerge in early childhood (see also Barnett, Citation2011; Carneiro & Heckman, Citation2003; Heckman, Citation2008; Paxson & Schady, Citation2007).

In Israel, as elsewhere, students from strong socio-economic backgrounds attain higher achievements on average than those from weak socio-economic backgrounds (Ayalon & Shavit, Citation2004; RAMA, Citation2019). Moreover, inequality in disposable income in Israel is among the highest in the OECD countries, and the share of households under the poverty line is higher than in any other developed country (National Insurance Institute, Citation2019; OECD, Citation2023b). The total poverty rate in Israel in 2019 was 17% and the poverty rate among 0–17 year-olds was 22%, one of the highest rates in the OECD countries (OECD, Citation2023c). The incidence of poverty among households with children under age 4 in Israel was even higher – 25% compared with 16% of households without children in that age group (Shay, Citation2022). Thus, it is possible that scholastic inequality in Israel is a reflection of the economic inequality among families, particularly when the latter is manifested during early childhood.

Family income in early childhood and educational achievements

The association between family income in early childhood and subsequent educational achievements has been attributed to aspects of children’s neurodevelopment, stress, sensory stimulation, parenting styles, and to socio-economic differences in the quality of early childhood education. We briefly review each of these mediating factors.

In early childhood the brain is particularly sensitive to external environmental stimuli and environmental experiences, which in turn affect its structural and functional organization. Thus, experiences and environmental influences at an early age can leave a lasting mark on the architecture of the developing brain (Shonkoff et al., Citation2012). On average, parents from particularly weak socio-economic backgrounds have less time and fewer resources to provide cognitive stimuli for their children (Spera, Citation2005) and often find it difficult to provide them with toys, books, and other learning tools (Sheridan & McLaughlin, Citation2014).

Family income is related to the total internal surface of the brain in areas responsible for language, reading, spatial perception, and executive function, especially among children in families with the lowest incomes (Noble et al., Citation2015). Most recently, an important study has reported a causal association between mothers’ income and the pattern and magnitude of EEG power in a child’s brain in its first year of life (Troller-Renfree et al., Citation2022), in neural regions that affect language and cognitive outcomes (Brito, Fifer, Myers, Elliott, & Noble, Citation2016; Gou, Choudhury, & Benasich, Citation2011).

Stress is an individual’s feeling of doubt in one's ability to deal with a particular situation at a particular period in time. Stress can diminish the functioning of essential nervous systems that are located in the prefrontal cortex, which are responsible for moderating social behaviour, planning, and emotions (Hyman & Cohen, Citation2013). During early childhood, the brain is particularly sensitive to stress, and chronic exposure to stress in early developmental stages can disrupt cognitive and emotional aspects of normal development causing a significant delay in the ability to learn (Kim et al., Citation2013; Lupien et al., Citation2009; Shonkoff et al., Citation2012). Poverty can induce stress through negative environmental stimuli that are caused for example by violence in the family and in the community, the breakdown of the families, frequent residential moves, job instability and unemployment, and also greater use of negative parenting strategies (Bradley & Corwyn, Citation2002; Conger, Ge, Elder Jr, Lorenz, & Simons, Citation1994; Lipina, Citation2016; McLoyd, Citation1990, Citation1998; Mullainathan & Shafir, Citation2013). Prolonged exposure of young children to chronic stress and socio-economic deprivation can disrupt the development of brain structure and increase the risk of low cognitive functioning that may persist into adolescence (Blair, Citation2010; Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, Citation2019; Kim et al., Citation2013; Lupien et al., Citation2009; Shonkoff, Citation2011; Shonkoff et al., Citation2012). Young children that experience the burden of their family’s economic and social stress are likely to enter the education system with increased risk of behavioural problems, poorer executive functioning and learning disabilities (Nelson & Sheridan, Citation2011; Phillips & Shonkoff, Citation2000).

Socio-economic strata differ in model parenting styles (Lareau, Citation1987, Citation2011). Middle-class families tend to concentrate on nurturing the knowledge, skills, and abilities of their children, whereas working class families tend to provide for the basic needs of their children, such as food, shelter, and physical necessities, investing less time and fewer resources in cognitive or cultural stimulation. More generally, educated parents invest more time in educational activity connected to early cognitive development, such as reading to their children (Mayer, Kalil, Oreopoulos, & Gallegos, Citation2015; Sandberg & Hofferth, Citation2001). Similarly, parents from a strong socio-economic background tend to talk to their infant children more, and in more complex ways, than parents from weaker socio-economic backgrounds, which in turn, impacts the development of infants’ vocabulary (Hart & Risley, Citation1995; Hoff, Laursen, & Tardif, Citation2002).

Families’ socio-economic background is also related to parents’ choices regarding the type, quality and intensity of the early childhood education and care (henceforth ECEC) programmes for their children (Blossfeld, Kulic, Skopek, & Triventi, Citation2017; Burger, Citation2010; Early & Burchinal, Citation2001; Fuller, Holloway, & Liang, Citation1996; Kulic, Skopek, Triventi, & Blossfeld, Citation2019; OECD, Citation2017). Parents of high socio-economic status are more likely to send their young children to ECEC frameworks outside the home (Kim & Fram, Citation2009), their children tend to participate in higher-quality ECEC programmes (Blossfeld et al., Citation2017; Del Boca, Citation2015; Kulic et al., Citation2019) and to spend more time in such frameworks (Early & Burchinal, Citation2001; Wolfe & Scrivner, Citation2004). In contrast, children from weak socio-economic backgrounds are more often placed in informal childcare arrangements (Early & Burchinal, Citation2001; OECD, Citation2017) and less likely to participate in high quality ECEC programmes (Blossfeld et al., Citation2017; Kulic et al., Citation2019). Attending high-quality ECEC can lead to a significant improvement in children’s skills, both cognitive and non-cognitive, which in the long term can improve educational and occupational opportunities (Barnett, Citation1985, Citation1996; Heckman, Moon, Pinto, Savelyev, & Yavitz, Citation2010; Schweinhart et al., Citation2005), and high-quality ECEC for disadvantaged populations can break the intergenerational cycle of poverty (Heckman & Karapakula, Citation2019).

Hypotheses

The objective of this study is to determine whether family income in early childhood is associated with future educational achievements of students in Israel. The literature that we reviewed suggests three hypotheses:

Family income during early childhood (from birth to age five) is associated with future educational achievements of children, even after controlling for family income at later ages and additional socio-demographic characteristics. The higher the family income in early childhood is, the higher is the child’s educational achievements in adolescence.

Relative poverty experienced in early childhood adversely affects future educational achievements, above and beyond the overall effects of families’ socio-economic and demographic characteristics.

The association between family income and poverty on the one hand, and future educational achievements on the other hand, is stronger when measured at ages 0–2 than at ages 3–5. This hypothesis is in line with the First 1,000 Days theory, according to which the sensitivity of infants’ brain to environmental influences diminishes with age.

Research method

The data requirements for testing these hypotheses are challenging. Ideally, one would want to conduct a controlled experiment in which family income is manipulated in early childhood and its effects are estimated at some later point in the life course (e.g. Troller-Renfree et al., Citation2022). Alternatively, a panel study could collect and analyze prospective longitudinal data that includes measures of family income, educational achievements and control variables at different ages of childhood. Both research designs would require lengthy waiting time for the subjects to mature between their early childhood and primary school ages. Unfortunately, in Israel there is no existing longitudinal survey that follows a large representative sample of children from birth to adulthood. As an alternative, we created a quasi-longitudinal database which merges several existing data sets to provide information on family socio-economic characteristics in early childhood and in adolescence, as well as standardized test scores taken in fifth-grade (approximately, at age 11).

The database was created, to our specifications, at the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS) by merging individual-level records from the Population and Housing Censuses for 1995 and 2008, the Central Population Registry and Meitzav test scores of the National Authority for Measurement and Evaluation in Education (RAMA, in Hebrew). The Meitzav achievement tests are national standardized tests taken in the fifth and eighth grades every year in four core subjects: mathematics, science, English as a foreign language, and language skills (Hebrew or Arabic). For the Meitzav, all schools in Israel are grouped into four clusters of approximately equal size, with each cluster being a representative sample of all Israeli schools.Footnote1 Each year, two of the four clusters take the Meitzav test (Blank & Shavit, Citation2016; RAMA, Citation2009). Student records were anonymized and merged with parents’ characteristics using unique identifiers.

The 1995 Census was conducted in October – November of 1995 and collected information on a variety of demographic variables on Israel’s population and households. A representative 20% sample of households was requested to fill out an extended questionnaire, which consisted of questions on education, income, ethnicity, religiosity, etc. These households were sampled in a way that represent the general households and population groups in Israel in 1995 (ICBS, Citation1999). Individual records from the 1995 census were merged with the subsequent sample of the 2008 census, providing us with repeated socio-economic measures of parents and subjects in their adolescence. In 2008 the extended information was available for 16% of the population.

The sample is restricted to subjects born in the five years preceding the 1995 census. Those same individuals were aged 13–18 at the time of the 2008 census. They were tested in fifth-grade Meitzav in 2000–2005. Of the total 135,000 children in this birth cohort, about 26,800 cases appear in the 1995 sample; of those, 4,288 appear in the 2008 sample, and for about 1,500 cases data are also available on Meitzav test scores. We limited the analysis to students tested in Hebrew because the number of complete cases for students tested in Arabic was insufficient to provide the necessary statistical power for testing our hypotheses. Thus, the analysis is largely limited to Jewish children and unfortunately excludes most Arab children who attended Arabic-speaking schools.

Variables

presents descriptive statistics for the variables used in the analysis. The dependent variables are fifth-grade test scores in mathematics, science, English and Hebrew (for details on the tests see RAMA, Citation2018). For each subject, we standardized Meitzav scores within each examination year to a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations of variables by birth cohorts.

Family income is measured as the monthly per capita household income, as measured in the 1995 and 2008 censuses. These two measures include labor income and national insurance benefits (government transfers). Monthly income was adjusted for the size of the household by dividing monthly household income by the square root of the number of household members. The income reported in the 2008 census was adjusted to 1995 Israeli Shekels.

In addition to the continuous income variables, we created dummy variables indicating whether the family’s per capita income was at the bottom quintile of the distribution. We refer to these dummy variables as Poor in 1995 and Poor in 2008. Similarly, and for the sake of symmetry, we defined dummies representing the top quintiles of the income distributions and refer to them as Affluent in 1995 and Affluence in 2008, respectively. We include these dummy variables in the regression analyses in order to determine whether being relatively poor or being relatively affluent affects educational achievements above and beyond the linear effect of per capita disposable income.Footnote2

A regression equation that includes three different measurements of the family’s income is liable to suffer from a high level of multicollinearity between the different measures, which may have an impact on the standard errors and on the estimated coefficients’ statistical significance. Therefore, we estimated the degree of multicollinearity between the variables by means of a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). The degree of multicollinearity between the three measures of income (continuous income, being poor and being affluent) was examined in all the age groups and found to be well below the threshold of 10 – with most being below 2 – indicating low multicollinearity (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, Citation1995).

Parents’ education is measured by the highest degree attained by either parent, consisting of five ordinal categories: (1) no education, including those who never attended school or did not obtain any diploma; (2) graduates of elementary or junior high schools; (3) high school graduates without a matriculation diploma; (4) high school graduates with either a matriculation diploma or a certificate from a post-secondary non-academic school; and (5) university or college graduates. Although this variable is measured on an ordinal scale, its relationship with the child’s achievement variables was approximately linear. Therefore, we treated this variable if it lies on an interval scale. Doing so does not affect the other coefficient estimates in any of the regression analyses.

We also control for several additional variables that are known to affect educational achievements: student’s gender (1 for girls and 0 for boys); the number of siblings in 1995 is indicated by the number of mother’s live births by the 1995 census, and an additional number of siblings was measured as her number of live births between the two censuses; and a dummy variable identifies whether the child was born in the first or second half of the calendar year. Some studies suggest that those born in January – June are older on average than their classmates and perform better scholastically (Bernardi, Citation2014; Bernardi & Grätz, Citation2015).Footnote3

Multivariate analyses

In order to estimate the effect of disposable per capita family income in early childhood on educational achievements at a later age, a multivariate linear regression analysis was performed. The three hypotheses were tested in four regression models of fifth-grade test scores in mathematics, science, English and Hebrew (). The regression equations include family income in the 1995 census (when the child was 5 years old or less), family income in the 2008 census (when the child was age 13–18 years old), parents’ education, family size, gender, and whether the child was born in the first half of the calendar year. In order to test whether there are differences between the two age groups in the effects of family income and poverty on educational achievements later in the life course, the analysis was carried out separately for the 1993–1995 cohort (who were under three years old in 1995) and the 1990–1992 cohort (who were 3–5 years old in 1995).

Table 2. OLS regression coefficients and standard errors of mathematics, science, English and Hebrew test scores for subjects born in 1993–1995 (ages birth – age two in 1995) and for subjects born in 1990–1992 (ages 3–5 in 1995).

For most of the respondents, the dependent variables were measured between 2000 and 2005, i.e. before the measurement of family income in 2008, thus we do not assume a causal effect of income at ages 13–18 on achievements in fifth-grade. Nonetheless, we controlled for the income variables in 2008 as a conservative control for families’ economic circumstances during adolescence, in order to reduce the extent to which the effect of income in 1995 mediates the effects of later income. We assume that the disposable family income per capita for families with children aged 10 is highly correlated with their income during the years when their children were aged 13–18. A similar calculation which is presented below shows that this correlation is about 0.60.

As noted, income, in both 1995 and in 2008, is measured using three different variables: a continuous measure of disposable income per capita, a dummy variable indicating that the income was in the bottom quintile (Poor) and a dummy indicting that it was in the top quintile (Affluent). Thus, we examined not just the linear effect of family income but also the effects of being located at the extremes of the income distribution.

The estimates shown in indicate that belonging to the lowest quintile in the family income distribution in 1995 has a negative effect on fifth-grade test scores in mathematics, science, English and Hebrew, even when controlling for income at a later stage, parents’ education, family size, and other variables in the regression equation. Importantly, it has a particularly strong and statistically significant negative effect when measured in birth – age two, compared with its measure in ages 3–5. Moreover, the differences between the two age groups in the effect of being relatively poor were found to be statistically significant.Footnote4 In other words, the effect of relative poverty experienced from birth to age two on fifth-grade achievements is greater than the effect of relative poverty at the ages 3–5.Footnote5 For example, for the achievement in mathematics, the meaning of the coefficient (b = −.323, p < .01) is that belonging to the lowest quintile of the income distribution from birth to age two results in a lower test score of about 32% of a standard deviation, while belonging to the lowest quintile at the ages 3–5 results in a lower test score of only 11% of a standard deviation (b = −.117, p > .05). Recall that the dependent variable is standardized to a standard deviation of 1. Interestingly, neither poverty nor affluence in 2008 showed statistically significant effects on test scores in fifth-grade, net of the continuous measure of income in 2008.

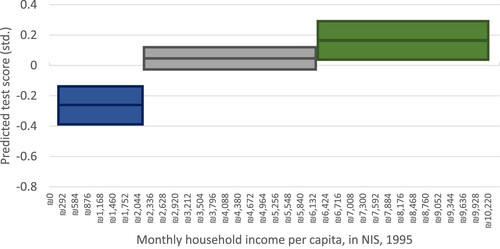

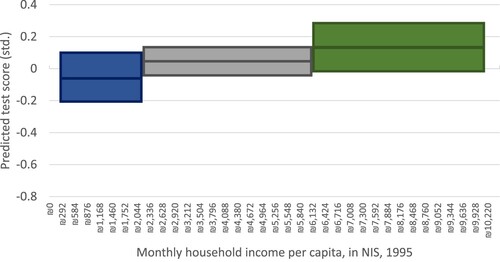

and illustrate the relationship between income and achievement. It plots the predicted fifth-grade standardized mathematics test scores by family income in 1995, and does so separately for the two birth cohorts. The middle line represents the average predicted incomes at three income levels: relative poverty, mid-level incomes, and relative affluence. The shading around the middle line represents the degree of variation in these effects (95% confidence intervals).Footnote6 The Figures show that the predicted mathematics test scores are not influenced by the change in continuous family income during early childhood. In contrast, the differences in the effect of relative poverty during early childhood on future achievement between the two age groups is evident: children from birth to age 2 whose family’s income was in the lowest quintile of the income distribution in 1995 achieve lower scores in their adolescence. This effect is not statistically significant for the older age group (ages 3–5 in 1995). In other words, relative poverty in the very first years in life has a statistically significant and large effect on future achievements. The graphs also show that belonging to the top quintile of the income distribution in early childhood (relative affluence) increases the child’s future achievements, but its effect is not statistically significant.

Sensitivity checks

Readers may wonder at this stage, why the negative effect of poverty at ages 0–2 two does not carry over to ages 3–5. Clearly, if families’ income were stable throughout these five years, the effects of poverty would be similar when measured in either of the two segments of early childhood. However, disposable per capita income varies considerably with time among families with young children. Mothers in Israel usually give birth in their late twenties and early thirties (ICBS, Citation2015). At these ages, there is a fair degree of economic mobility (Romanov & Zussman, Citation2003) due to changes over time in labour force participation rates, seniority at work, acquisition of higher education, and job mobility. The correlation in salary income between 1993 and 1996 among subjects ages 25–34 was 0.68 (ibid). Moreover, only half (49%) of the poor (those in the lowest income quintile) remains poor for three years or more. Mobility between categories of total disposable income per capita is even higher among families with very young children, because per capita income varies by family size, maternity allowance, and family allowance, and because mothers transition in and out of maternity leave.

Rubashevski-Banit (Citation2019) presents a joint distribution of the disposable income quintiles for households where the head of household is between the ages of 25 and 27 and five years later (when the head of the household is between 30 and 32). She shows that a substantial share of the households moved between income quintiles during the five-year interval. The correlation between disposable per capita income quintile of the household head in ages 25–27 and five years later is only 0.39 (our computation).

The still skeptical reader may be persuaded by the following argument. Ideally, the data that we analyzed should have included measurements of poverty for both age groups (birth – age two and ages 3–5). This would have made it possible to estimate the effect of each of the poverty measurements on future achievement. We refer to these two effects in their standardized form as a and b. Unfortunately, we do not possess repeated measurements and must estimate the influence of poverty in each age group separately. We refer to the estimates for fifth-grade mathematics as a* and b*, their values being −.128 and −.043, respectively (see columns 1 and 2, respectively in ). It can be shown that the following equalities hold: b* = b + ra; a* = a + rb, where r is the correlation between disposable per capita income for the two age groups. Based on the aforementioned calculation, it can be assumed that this correlation is about equal to 0.39. The solution of the equations for the two unknowns – a and b – yields −.152 and −.061, respectively. In other words, the finding that the effect of poverty from birth to age two is much stronger than for children ages 3–5 would be correct even if we had measurements of income for the same subjects at both ages.

Discussion

This study shows that belonging to the lowest quintile of the income distribution during early childhood is negatively associated with future educational achievements, and that this association remains statistically significant after controlling for family income at later ages, parents’ education, gender, family size, and month of birth. These findings are consistent with prior research, which found an effect of poverty in early childhood on various outcomes later in life (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, Citation1997; Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebanov, Citation1994; Lupien et al., Citation2009).

Importantly, we also found that the effect of poverty in early childhood on future educational achievement is stronger when measured at ages 0–2 than when measured at ages 3–5. This finding lends support to the claim that children are more sensitive to the effects of the family and social environment on their cognitive development during the first years of life (Levitt, Citation2009).

The results of the research are likely to have important implications for social policy. First and foremost, the research demonstrates the importance of reducing the extent and incidence of poverty among children and particularly poverty in the very first years of life. A possible policy measure toward this end is to shift part of the child allowance that families with children receive from the State from adolescence to infancy. Currently, the child allowances in Israel are universal and are paid in equal installments from birth to age 18 (Wasserstein, Citation2016). Given the findings in this study, investments made during the early years of life, and particularlly at ages 0–2, may yield greater long-term effects on students’ academic achievements. Therefore, it may be worthwhile to consider redistributing child allowances in favor of younger ages (and possibly families from lower socio-economic strata).

Consideration should also be given to the quality of ECEC facilities in Israel. Despite the high fertility rate among Israeli women (OECD, Citation2023a), employment rates of mothers of infants are very high (Vaknin, Citation2020), as are children’s enrolment rates in ECEC in Israel (OECD, Citation2017; Vaknin, Citation2020). However, only 20% of the children in this age group attend supervised childcare frameworks (National Council for the Child, Citation2016). Studies have shown that the participation of children in high-quality ECEC can improve their future achievements, particularly in the case of children from weaker socio-economic backgrounds (Barnett, Citation1985, Citation1996, Citation2011; Duncan, Citation2003). Unfortunately, the likelihood of attending quality ECEC is related to families’ socioeconomic conditions (Kulic et al., Citation2019). Therefore, the poor, who are most likely to gain from quality ECEC, are also least likely to attend quality frameworks.

An important limitation of this study is the absence of repeated measurements of income during childhood. Research has shown that the cumulative time spent in poverty during early childhood has a decisive effect on cognitive development (e.g. Guo, Citation1998). To estimate the cumulative effect of poverty in early childhood on students’ educational achievements, repeat measurements of family income over time are needed, as well as repeat measurements of educational achievements throughout childhood. Unfortunately, we did not have access to continuous measures of family income for Israel, and had to rely on income measures at discrete points in time. A second limitation of the study is the small sample of Arabs, and the near absence of ultra-orthodox Jews most of whom do not sit for Meitzav tests. In future research, we aim to replace the census records with annual income tax records for parents. This will create a much larger sample, especially for Arabs, and will enable us to measure income continuously from birth of the subject until the test scores.

In summary, the effect of the timing and duration of poverty on the life circumstances of children in Israel has not been studied extensively. As noted, many Israeli children live in relative poverty (OECD, Citation2023c; Shay, Citation2022) and educational inequalities among them are substantial (RAMA, Citation2018, Citation2019). Our finding that poverty in very early childhood is associated with poor academic achievements in primary school may explain Israel's low performance in international tests (RAMA, Citation2019). Furthermore, these developmental gaps may account in part for the inequalities in educational achievement observed between socioeconomic strata in Israel. Thus, this study makes a unique contribution to the investigation of the transmission of inequalities between generations and of educational inequalities in Israel. The understanding that families' economic resources during the very first years of life may have long-term effects on children's educational achievements may convince policy makers to increase or redistribute public investments in those ages.

Acknowledgments

We thank Avi Weiss and Alex Weinreb for their helpful comments on earlier versions of the paper. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dana Shay

Dana Shay is a PhD candidate at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Tel Aviv University; Researcher in the Taub Center Initiative on Early Childhood Development and Inequality.

Yossi Shavit

Yossi Shavit is Professor Emeritus at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Tel Aviv University; Chair of Taub Center Initiative on Early Childhood Development and Inequality.

Isaac Sasson

Isaac Sasson is Associate Professor at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Tel Aviv University.

Notes

1 Except for ultra-orthodox schools, whose students do not usually participate in national tests.

2 These dummy variables are based on the distribution of income among the sample. As noted, our database is a representative sample of households with children who were born in 1990–1995. In unreported analyses we experimented with measures of Poor and Affluent that were based on both the population and the sample family income quintiles. These results of the two were similar and ultimately, we chose to report the latter.

3 In additional analyses (not shown) we included immigrant status, indicating that respondent was not born in Israel, but its inclusion did not substantially affect the remaining coefficients.

4 In order to test the significance of the differences between the two age groups (birth–age 2 versus ages 3–5) a dummy variable for the interaction between age group and each of the other independent variables in the model (family income, parents’ education, number of siblings, etc.) was added.

5 One may wonder if the weaker estimates of the direct effect of poverty that is experienced in ages 3–5 is not due to its stronger correlations with other variables in the equation. If that were the case, it could be claimed that the effects of income in the 3–5 age group are ‘swallowed up’ by the other variables in the model. We refute this hypothesis in comparisons of the Pearson correlations between family income in 1995 and in 2008, with the other independent variables in the regressions. The comparison shows that the older group the correlations involving income in 1995 are much weaker than in the younger group, and that the correlations involving 2008 income are weaker in the older group (except one correlation) but not only slightly so. These results tend to refute the hypothesis that the age differences in the effects of poverty are due to differences between the groups in the inter-correlations among the dependent variables.

6 The prediction of the graphs was based on the existing model, which includes both the statistically significant effects and the statistically insignificant effects of the three income measures during early childhood (continuous income, being relatively poor or affluent), and at the mean value of the other variables included in the regressions, including average income in 2008.

References

- Ayalon, H., & Shavit, Y. (2004). Educational reforms and inequalities in Israel: The MMI hypothesis revisited. Sociology of Education, 77(2), 103–120. doi:10.1177/003804070407700201

- Barnett, W. S. (1985). Benefit-cost analysis of the perry preschool program and its policy implications. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 7(4), 333–342. doi:10.3102/01623737007004333

- Barnett, W. S. (1996). Lives in the balance: Age-27 benefit–cost analysis of the high/scope perry preschool program, high/scope educational research foundation monograph no.11. Ypsilanti, MI: High Scope Press.

- Barnett, W. S. (2011). Effectiveness of early educational intervention. Science, 333(6045), 975–978. doi:10.1126/science.1204534

- Bernardi, F. (2014). Compensatory advantage as a mechanism of educational inequality: A regression discontinuity based on month of birth. Sociology of Education, 87(2), 74–88. doi:10.1177/0038040714524258

- Bernardi, F., & Grätz, M. (2015). Making up for an unlucky month of birth in school: Causal evidence on the compensatory advantage of family background in England. Sociological Science, 2, 235–251.

- Blair, C. (2010). Stress and the development of self-regulation in context. Child Development Perspectives, 4(3), 181–188. doi:10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00145.x

- Blank, C., & Shavit, Y. (2016). The association between student reports of classmates’ disruptive behavior and student achievement. Aera Open, 2(3), 1–17. doi:10.1177/2332858416653921

- Blass, N. (2020). Achievements and gaps: The education system in Israel – A status report. Jeruaslem: Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel. https://www.taubcenter.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/achievementsangapseng.pdf

- Blossfeld, H. P., Kulic, N., Skopek, J., & Triventi, M. (eds.). (2017). Childcare, early education and social inequality: An international perspective. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 371–399.

- Brito, N. H., Fifer, W. P., Myers, M. M., Elliott, A. J., & Noble, K. G. (2016). Associations among family socioeconomic status, EEG power at birth, and cognitive skills during infancy. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 19, 144–151. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2016.03.004

- Brooks-Gunn, J., & Duncan, G. J. (1997). The effects of poverty on children. The Future of Children, 7(2), 55–71. doi:10.2307/1602387

- Burger, K. (2010). How does early childhood care and education affect cognitive development? An international review of the effects of early interventions for children from different social backgrounds. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25(2), 140–165. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.11.001

- Carneiro, P., & Heckman, J. J. (2003). Human capital policy. In J. J. Heckman, & A. B. Krueger (Eds.), Inequality in America: What role for human capital policies? (pp. 77–237). Cambridge Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2019). Toxic stress. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/toxic-stress/.

- Conger, R. D., Ge, X., Elder Jr, G. H., Lorenz, F. O., & Simons, R. L. (1994). Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development, 65(2), 541–561. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00768.x

- Cunha, A. J. L. A. D., Leite, ÁJM, & Almeida, I. S. D. (2015). The pediatrician's role in the first thousand days of the child: The pursuit of healthy nutrition and development. Jornal de Pediatria, 91, S44–S51. doi:10.1016/j.jped.2015.07.002

- Del Boca, D. (2015). Childcare choices and child development. IZA World of Labor, 134, 1–10. doi:10.15185/izawol.134

- Duncan, G. J. (2003). Modeling the impacts of child care quality on children's preschool cognitive development. Child Development, 74(5), 1454–1475.

- Duncan, G. J., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Klebanov, P. K. (1994). Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Development, 65(2), 296–318. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00752.x

- Early, D. M., & Burchinal, M. R. (2001). Early childhood care: Relations with family characteristics and preferred care characteristics. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 16(4), 475–497. doi:10.1016/S0885-2006(01)00120-X

- Farkas, G, & Beron, K. (2004). The detailed age trajectory of oral vocabulary knowledge: Differences by class and race. Social Science Research, 33(3), 464–497. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2003.08.001

- Feinstein, L. (2003). Inequality in the early cognitive development of British children in the 1970 cohort. Economica, 70(277), 73–97. doi:10.1111/1468-0335.t01-1-00272

- Fuller, B., Holloway, S. D., & Liang, X. (1996). Family selection of child-care centers: The influence of household support, ethnicity, and parental practices. Child Development, 67(6), 3320–3337. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01916.x

- Gou, Z., Choudhury, N., & Benasich, A. A. (2011). Resting frontal gamma power at, 16, 24. and 36 months predicts individual differences in language and cognition at 4 and 5 years. Behavioural Brain Research, 220(2), 263–270. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2011.01.048

- Guo, G. (1998). The timing of the influences of cumulative poverty on children's cognitive ability and achievement. Social Forces, 77(1), 257–287. doi:10.1093/sf/77.1.257

- Hair, J. F. Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1995). Multivariate data analysis, 3rd edition. New York: Macmillan.

- Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of young American children. Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks.

- Heckman, J. J. (2008). Schools, skills, and synapses. Economic Inquiry, 46(3), 289–324. doi:10.1111/j.1465-7295.2008.00163.x

- Heckman, J. J. (2011). The economics of inequality: The value of early childhood education. American Educator, 35(1), 31–47.

- Heckman, J. J., & Karapakula, G. (2019). Intergenerational and intragenerational externalities of the perry preschool project. The Heckman Equation Project, doi:10.3386/w25889

- Heckman, J. J., Moon, S. H., Pinto, R., Savelyev, P. A., & Yavitz, A. (2010). The rate of return to the HighScope perry preschool program. Journal of Public Economics, 94(1–2), 114–128. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.11.001

- Hoff, E., Laursen, B., & Tardif, T. (2002). Socioeconomic status and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Biology and ecology of parenting (2nd ed., pp. 231–252). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Hyman, S. E., & Cohen, J. D. (2013). Disorders of mood and anxiety. In R. E. Kandel, H. J. Schwartz, T. M. Jessell, S. A. Siegelbaum, & A. J. Hudspeth (Eds.), McGraw- hill, S. M. Principles of neural science (5th ed., pp. 1402–1424). NY: McGraw Hill.

- ICBS. (1999). Census of population and housing 1995. Jerusalem: Central Bureau of Statistics.

- ICBS. (2015). Fertility rates, by Age and religion, table 3.13. In statistical abstract of Israel 2015 No.66, Jerusalem: Central Bureau of Statistics.

- Kim, J., & Fram, M. S. (2009). Profiles of choice: Parents’ patterns of priority in child care decision-making. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24(1), 77–91. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.10.001

- Kim, P., Evans, G. W., Angstadt, M., Ho, S. S., Sripada, C. S., Swain, J. E., … Phan, K. L. (2013). Effects of childhood poverty and chronic stress on emotion regulatory brain function in adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(46), 18442–18447. doi:10.1073/pnas.1308240110

- Kulic, N., Skopek, J., Triventi, M., & Blossfeld, H. P. (2019). Social background and children's cognitive skills: The role of early childhood education and care in a cross-national perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 45, 557–579. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073018-022401

- Lareau, A. (1987). Social class differences in family-school relationships: The importance of cultural capital. Sociology of Education, 60(2), 73–85. doi:10.2307/2112583

- Lareau, A. (2011). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. California: University of California Press.

- Levitt, C. A. (2009). From best practices to breakthrough impacts: A science-based approach to building a more promising future for young children and families. Cambridge, MA: Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University.

- Lipina, S. J. (2016). The biological side of social determinants: Neural costs of childhood poverty. Prospects, 46(2), 265–280. doi:10.1007/s11125-017-9390-0

- Lupien, S. J., McEwen, B. S., Gunnar, M. R., & Heim, C. (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 434–445. doi:10.1038/nrn2639

- Mayer, S. E., Kalil, A., Oreopoulos, P., & Gallegos, S. (2015). Using behavioral insights to increase parental engagement: The parents and children together (PACT) intervention (No. w21602). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- McLoyd, V. C. (1990). The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development, 61(2), 311–346. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x

- McLoyd, V. C. (1998). Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist, 53(2), 185–204. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.185

- Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: Why having too little means so much. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- National Council for the Child. (2016). The state of young children in Israel 2015. Jerusalem: The National Council for the Child. https://bernardvanleer.org/app/uploads/2016/03/The-State-of-Young-Children-in-Israel-2015_hi-res.pdf.

- National Insurance Institute. (2019). Poverty and social gaps - annual report, 2018. Jerusalem: National Insurance Institute. https://www.btl.gov.il/Publications/oni_report/Pages/oni2018.aspx

- Nelson, C., & Sheridan, M. A. (2011). Lessons from neuroscience research for understanding causal links between family and neighborhood characteristics and educational outcomes. In G. J. Duncan, & R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Whither opportunity? Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances (pp. 27–46). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Noble, K. G., Houston, S. M., Brito, N. H., Bartsch, H., Kan, E., Kuperman, J. M., … Schork, N. J. (2015). Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nature Neuroscience, 18(5), 773–780. doi:10.1038/nn.3983

- OECD. (2017). Starting strong 2017: Key OECD indicators on early childhood education and care. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/starting-strong-2017_9789264276116-en

- OECD. (2023a). Fertility rates (indicator). (Accessed on, 20, June 2023). doi:10.1787/8272fb01-en.

- OECD. (2023b). Income inequality (indicator). (Accessed on, 20, June 2023). doi:10.1787459aa7f1-en.

- OECD. (2023c). Poverty rate (indicator). (Accessed on, 20, June 2023). doi:10.1787/0fe1315d-en.

- Paxson, C., & Schady, N. (2007). Cognitive development among young children in Ecuador the roles of wealth, health, and parenting. Journal of Human Resources, 42(1), 49–84. doi:10.3368/jhr.XLII.1.49

- Phillips, D. A., & Shonkoff, J. P. (eds.). (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

- RAMA. (2009). MEIZTAV 2009: Indicators of school effectiveness and growth. Ramat-Gan: National Authority for Measurement and Evaluation in Education.

- RAMA. (2018). Meitzav 2018 - measures of school efficiency and growth. Ramat-Gan: National Authority for Measurement and Evaluation in Education. https://meyda.education.gov.il/files/Rama/Meitzav_Hesegim_Report_2018.pdf.

- RAMA. (2019). Pisa 2018: Literacy among 15-year-olds in science, Reading, and math. Ramat-Gan: National Authority for Measurement and Evaluation in Education. https://meyda.education.gov.il/files/Rama/PISA_2018_Report.pdf.

- Romanov, D., & Zussman, N. (2003). Labor income mobility and employment mobility in Israel, 1993–1996. Israel Economic Review, 1(1), 81–102. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2171743.

- Rosenzweig, M. R. (2003). Effects of differential experience on the brain and behavior. Developmental Neuropsychology, 24(2–3), 523–540. doi:10.1080/87565641.2003.9651909

- Rubashevski-Banit, V. (2019). The changes in the rates of first-time home buyers among young people according to income level, in the years 2007–2016. Jerusalem: Bank of Israel, Research Division. https://boi.org.il/media/iwohgouk/%D7%A8%D7%95%D7%9B%D7%A9%D7%99-%D7%93%D7%99%D7%A8%D7%94-%D7%A8%D7%90%D7%A9%D7%95%D7%A0%D7%94.pdf.

- Sandberg, J. F., & Hofferth, S. L. (2001). Changes in children’s time with parents: United States, 1981–1997. Demography, 38(3), 423–436. doi:10.1353/dem.2001.0031

- Schweinhart, L. J., Montie, J., Xiang, Z., Barnett, W. S., Belfield, C. R., & Nores, M. (2005). Lifetime effects: The high/scope perry preschool study through age 40. Ypsilanti. MI: High/Scope Press.

- Shay, D. (Ed.). (2022). Early childhood in Israel: Selected research findings, 2022. Jerusalem: Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel. https://www.taubcenter.org.il/en/research/early-childhood-in-israel-2022/.

- Sheridan, M. A., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2014). Dimensions of early experience and neural development: Deprivation and threat. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(11), 580–585. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2014.09.001

- Shonkoff, J. P. (2011). Protecting brains, not simply stimulating minds. Science, 333(6045), 982–983. doi:10.1126/science.1206014

- Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., Siegel, B. S., Dobbins, M. I., Earls, M. F., McGuinn, L., … Wood, D. L. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2663

- Spera, C. (2005). A review of the relationship among parenting practices, parenting styles, and adolescent school achievement. Educational Psychology Review, 17(2), 125–146. doi:10.1007/s10648-005-3950-1

- Troller-Renfree, S. V., Costanzo, M. A., Duncan, G. J., Magnuson, K., Gennetian, L. A., Yoshikawa, H., … Noble, K. G. (2022). The impact of a poverty reduction intervention on infant brain activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119, 5. doi:10.1073/pnas.2115649119

- Vaknin, D. (2020). Early childhood education and care in Israel compared to the OECD: Enrollment rates, employment rates of mothers, quality indices, and future achievement. Jerusalem: Taub Center of Social Policy in Israel.

- Wasserstein, S. (2016). Recipients of child benefit in 2015. Jerusalem: National Insurance Institute Research and Planning Administration. https://www.btl.gov.il/Publications/survey/Documents/seker_284.pdf.

- Wolfe, B., & Scrivner, S. (2004). Child care use and parental desire to switch care type among a low-income population. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 25(2), 139–162. doi:10.1023/B:JEEI.0000023635.67750.fd