ABSTRACT

The literature defines curiosity and interest, but it is not clear how interest can be generated, where interest is positioned in the learning process, and what the impact of interest is on cognitive and emotional development.

This paper reports on a three-year, iterative design-based research project involving three separate cohorts totalling 57 early learners in an early learning setting in Southern Queensland, Australia. The young learners aged 4–5 years, engaged in an enrichment program that extended over a two-week period for each of 15 topics.

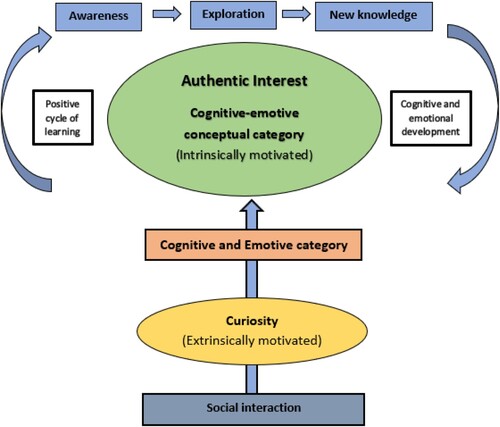

Insights were gained on how young children developed interested in a topic. An emergent model of authentic interest was developed, showing how interest is situated centrally in the learning process. It also shows how interest raised awareness, exploration, and new knowledge, creating a cycle of repeated engagement with the topic, thereby enhancing cognitive and emotional development.

Introduction

Curiosity is a natural asset for learning in the early years, attracting children to be captivated in the moment. Taking an interest beyond curiosity takes this to an enduring state of attention. It is this shift from curiosity to sustained interest, known as authentic interest in this study, that was explored in the research presented here.

Both curiosity and interest have been acknowledged as contributing to cognitive development and success in learning. ‘Interest’ is widely regarded as a powerful motivational process that energises learning and is regarded as essential to academic success because students with authentic interest are more likely to pay attention, become engaged, and ultimately perform well (Harackiewicz, Smith, & Priniski, Citation2016). Although the literature attempts to define curiosity and interest, it is not clear how interest develops, where it is positioned in the learning process, and what the cognitive, emotional, and behavioural impact is of having an interest in a specific topic, providing an opportunity for an exploration into these questions.

This research focusses on exploring interest development in the early years, which, from a neuro-biological perspective, is an ideal time to focus on the generation of curiosity and developing interest. Fuhrmann, Knoll, and Blakemore (Citation2015) describe early childhood as the first period of heightened malleability. Neuro-biological evidence suggests that young children are in the sensitive or critical period for language development with synapse formation in the prefrontal cortex is at its highest between the age of 12 months and 6 years (Prime Minister’s Science Engineering and Innovation Council [PMSEIC] , Citation2009). Doidge (Citation2010) noted that during this critical period, the cortex is so plastic that its structure can be changed by exposing it to new stimuli.

The research was therefore specifically aimed at children aged 4 and 5, when they are in the first period of heightened malleability (Fuhrmann et al., Citation2015), when synaptic formation in the prefrontal cortex is high (PMSEIC, Citation2009) and they are still in the sensitive period for language development (Council for Early Childhood Development, Citation2010).

Defining curiosity and interest

Despite suggestions that trying to define curiosity and interest is fraught with issues such as subjectivity and ambiguity (Murayama, Fitzgibbon, & Sakaki, Citation2019), an attempt will be made to describe these two concepts by reviewing relevant literature.

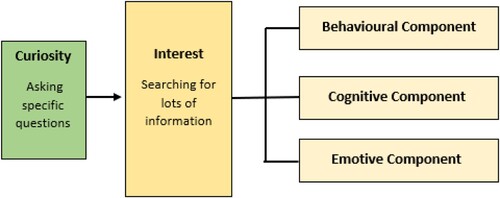

The concept of interest encompasses two distinct, yet similar components, namely being curious and taking an interest. Interest is both a psychological state of attention and an affect toward a particular object or topic (situational interest); and an enduring predisposition to reengage over time (Harackiewicz et al., Citation2016). In this research, situational interest is equated to curiosity – a temporary experience of being captivated by something (Harackiewicz et al., Citation2016). According to Renninger and Hidi (Citation2016), curiosity tries to answer a specific question while interest is searching for lots of information. Dewey (Citation1913) qualifies curiosity as a fleeting phenomenon, where a child’s interest is momentarily caught, and interest as more enduring phenomenon where interest is held. This layered effect not only highlights the richness of the interest concept but also contributes to the challenge of understanding the process of interest development.

Interest also combines affective qualities, such as feelings of enjoyment and excitement, with cognitive qualities, such as focused attention and perceived value (Renninger & Hidi, Citation2016). Interest therefore has a behavioural component, as demonstrated by the predisposition to engage with the topic; a cognitive component, meaning it is accompanied by some form of knowledge about the topic of interest; and an emotive component, as the interested individual experiences emotion (Paul, Citation2013). illustrates the various components of interest and their derivation from curiosity. Curiosity is the initial spark that ignites interest in a particular topic. When children are curious, they naturally ask questions related to the topic. As their interest grows, they engage more deeply, and begin to uncover new knowledge which further fuels their interest. The three components of interest, behavioural, cognitive, and emotive, are all key components of interest that connect to each other (Paul, Citation2013; Gibbs & Poskitt, Citation2010). As children gain more knowledge and skills related to a topic, they often experience a sense of competence which reinforces their interest and their desire to continue learning and exploring. Emotional resonance plays a crucial role in shaping interest. When a child to makes an emotional connection with the topic, it can ignite their enthusiasm to learn more and actively engage with the topic.

Other early childhood specialists such as Maria Montessori who is known for her philosophy of education that bears her name and Lev Vygotsky who focused on the psychological development of children, have both made valuable contributions to how interest can be viewed (Bodrova, Citation2003). Montessori referred to the ‘natural’ interest that children have in learning, while Vygotsky viewed interest as being ‘shaped’ by the people and cultural artefacts that makes up the child’s environment. For Montessori, construction primarily takes place within a child as this child ‘unfolds’ his or her natural interest in learning. This view of learning determined her approach to instruction: she considered the preschool years to be the period of discovery, where children engage in the projects they choose and discover things in the areas of their own interest. The adult role, according to Montessori, is to direct the process by making sure that when each child displays both readiness and interest, he/she is given an opportunity for discovery (Bodrova, Citation2003). In contrast, for Vygotsky, other people and cultural artefacts that make up the child's environment do more than simply modifying what is coming from within the child, they shape both the content and the nature of this child's emergent mental functions. Vygotsky proposed a different type of learning, better described as assisted discovery, where the child integrates the results of his/her independent discoveries with the new knowledge taught in a systematic and structured way (Bodrova, Citation2003). The viewpoints of Montessori and Vygotsky regarding the development of interest are not mutually exclusive. Both viewpoints, natural interest, and shaped interest, are compatible and integrated as they form a broader understanding of the development of interest.

The current study

The study on the topic of interest in the early years focussed on three key research questions: How can interest be generated effectively in the early years? Where is interest positioned in the learning process? What is the impact of interest? The data was used to inform the response to the research questions.

The first challenge of the research was to generate interest in a consistent and structured way in a range of topics. For this aim, content-rich enrichment programs were developed specifically for the study. Hirsch (Citation2015) states an enrichment program must be rich with interesting content as a curriculum that is anything less, will be letting young children down. The programs covered a wide range of topics with the aim of providing children with a broad knowledge base and many starting points for learning. Hirsch (Citation2015) refers to this knowledge base as ‘core’ knowledge. The rationale behind the selection of the topics was choosing topics that provide a core body of knowledge, a body of knowledge that ought to be part of education according to Hirsch (Citation2015) but that are not necessarily in the national curriculum. The topics were not usually associated with the age group, so as not to interfere with the standard curriculum being taught. Bentley (Citation2000) states that an education enrichment program is defined as a program with a range of strategies designed to broaden or deepen learning and may involve exposure to new subjects that are not usually associated with an age group.

The topics were chosen from various plant, animal, people, or planet-related topics that were delivered in three cycles. Cycle 1 topics were: reptiles, continents, countries, trees, space; Cycle 2 topics were: mammals, the human body, insects, flowers, and birds; and Cycle 3 topics were: religions, famous works of art, dinosaurs, structures, and arachnids.

The choice of these topics of interest was motivated by the idea that they would increase the existing knowledge base of the children. A wide knowledge base is an important factor that shapes learning as it provides the basis on which new learning can build and helps children to make sense of new information (PMSEIC, Citation2009). It is acknowledged that many more topics of interest could have been included, but for research purposes 15 topic was considered sufficient.

Method

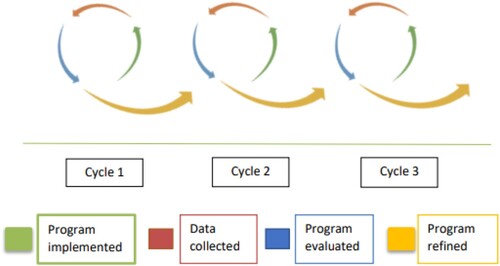

Interest development in the early years was explored via the implementation of enrichment programs that were developed as a learning experience and delivered in a longitudinal study using design-based research. Collins (Citation1992) defines design-based research as a systematic methodology for conducting design experiments in education to determine how different learning-environment designs affect dependent variables in teaching and learning. The study consisted of three iterative cycles of delivery and data collection over three years, with refinement of solutions in practice, see . Within each yearly cycle the programs were implemented; data was collected regarding interest development in terms of behavioural, emotional, and cognitive engagement; the programs were evaluated in terms of their ability to engage the children; and the programs were refined.

Participants

The participants in this study consisted of three different groups of 4–5-year-old children who attended a pre-preparatory class in an Australian early learning setting over a period of three years. As it was design-based research the single setting allowed for fewer variables in this iterative approach. The socio-economic (IRSD) index of the area reflected relative disadvantage: low income, low educational attainment, high unemployment, and people with low-skilled occupations (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2016). The groups were similar in size with the ratio of boys to girls being similar as well. Group sizes varied from day to day depending on attendance but there was an average of 18 participants (10 boys, 8 girls) in the project in the first cycle, an average of 19 participants (9 boys, 10 girls) in the second year, and an average of 20 participants (10 boys, 10 girls) in the third cycle, a total of 57 early learners. Other participants in the study included 57 parents or guardians, the teacher (TT1), the classroom assistant (TT2), and the researcher. Ethical clearance was obtained for this study.

The children were introduced to five topics in the third and fourth term (second semester) of each year. As they attended 5 days of school every 2 weeks, five sessions of the enrichment program were implemented with the whole class over a 2-week period. Therefore, fifteen programs, five per year, were conducted over a 3-year period.

Each session, approximately 20 min in duration, included a new area of focus and revision of the key concept of previous sessions. For example, the focus areas for the topic, ‘Trees’ were based on five trees commonly found in the surrounding environment: Eucalyptus (Gum) trees, Golden Wattle, Melaleuca (Tea Tree), Banksia and Pine Tree.

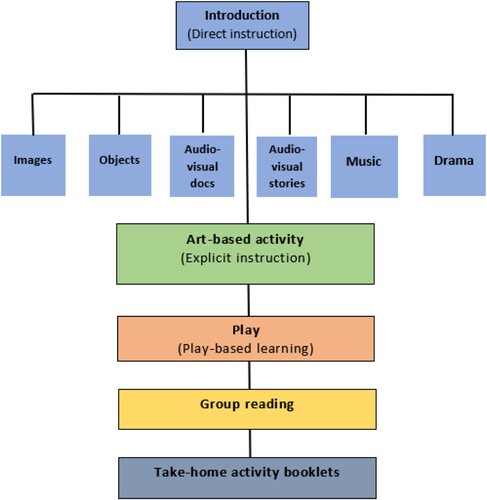

The enrichment programs were delivered via a blended approach of direct instruction, explicit instruction, play-based learning, group reading, and take-home activity booklets. The first part of the program was teacher initiated direct instruction. Intentional teaching of pre-planned content and activities were delivered to the class. This approach began with an introduction to the topic, followed by multiple possible combinations of key components (large realistic images, objects, audio-visual documentaries, audio-visual stories, music, and drama) delivered during a 20-minute session. The second approach was explicit instruction where the teacher explained, demonstrated, or modelled an art-based activity related to the topic, after which the children attempted the activity on their own. The third part of the program was play-based learning where the teacher provided play provocations related to the topic of interest. The play-based part of the program included a group reading later in the day, of a book specifically chosen to extend interest in the topic. Parental participation was encouraged via take-home activity booklets. With the aid of an activity booklet for each topic, parents and children were encouraged to do activities such as finding Eucalyptus leaves or Golden Wattle flowers in their environment. The activities reinforced the learning that occurred at school and further invigorated curiosity and interest.

provides a sequential model of the components of the blended approach used in the enrichment program.

Data collection

The emergent theoretical model that developed from this project was informed by four sources of data collected throughout the three cycles: questionnaires completed by the parents; pre and post knowledge tests administered to the children; observations made via video material and photos; and teacher talk.

According to Fredericks et al. (Citation2004) and Gibbs and Poskitt (Citation2010), behavioural engagement is indicated by paying attention, participating, and following instructions; cognitive engagement is indicated by volition learning and actively thinking about the information, and emotional engagement is indicated by showing interest, enjoyment, and happiness, and by reacting to the teacher.

Data on the behavioural and emotive component of interest were collected by observing video material and photos taken during the delivery of each session of each program; researcher notes; and feedback provided by both the teacher (TT1) and the classroom assistant (TT2). Data analysis included a detailed analysis of one randomly chosen session from each topic, providing an overview of emotional and behavioural engagement. The data recording provided an overview of each session showing the time and duration of each component, what the activity was, and how many students were disengaged during that component. For example, in the ‘Flower’ topic, a drama activity where the children pretended to be flowers was 2 min in duration. Two children showed some disengagement towards the end of the activity. Comments made by the researcher and thoughts on possible reasons for disengagement were included. Each component of the session was similarly identified and analysed providing a snapshot of engagement during the session. Assessments of low, medium, or high emotional engagement of the class were recorded using a self-designed protocol with three categories: verbal reactions, facial expressions and body language.

Data on the cognitive component of interest were collected by testing the children’s basic knowledge of the topic and understanding of concepts and terminology related to the topic before onset and after completion of each 2-week program. Cognitive engagement in the Flower program was indicated by the knowledge and understanding that the children had of flowers. They were asked to draw a stem, leaves, and roots on a picture of a flower. This provided insight into their understanding of the concepts. Even though all the students knew what a flower was in the pre-test phase, many did not have a basic understanding of the basic parts: the stem, leaves, and roots. There was a marked increase in the number of children who, after completing the enrichment program, were able to draw a stem (from 3 to 17), draw leaves (from 4 to 14) and draw roots (from 1 to 11). The children’s knowledge of types of flowers was minimal, with only three children knowing the names of some flowers. The children were shown pictures of a wide range of flowers and asked to point to certain flowers commonly seen in their environment such as a rose, a sunflower, a dandelion, etc. After participating in the program their knowledge of the types of flowers that they learned about in the program had improved significantly. For example, the number of children able to identify a rose had increased from 2 to 16, the number of children able to identify a dandelion has increased from 1 to 18; indicating that cognitive engagement with the program was high.

Further data on interest development was collected by recording themes and verbalisations in play during the day. Social interactions between children were captured with video recordings and jottings. It was evident that the curiosity generated by the Flower program inspired creative play as seen in the drawing and painting of flowers, exploratory play such as examining and deconstructing flowers, and active play such as planting and watering flowers.

After completion of each program, a post-test questionnaire was sent to the parents providing additional information on each child’s level of interest in a topic. For example, the parents were asked whether the Flower program had increased their child’s interest in flowers considerably, slightly, or not at all. They were asked what behaviour they had noticed since their children had participated in the program, for example, being more aware about flowers in their environment, wanting to pick flowers, etc. Feedback from the parents was used to corroborate the play observations made at school.

Comprehensive and cumulative documentation was utilised providing an insight into the dynamics of interest. The focus of the research was on characterizing the development of interest in the various topics in all its complexity and developing a theory that represents the development of interest in practice.

Results

A wealth of data was generated from the research from which a theoretical model of authentic interest development emerged. The process of how interest developed, based on a triangulation of the data sources, is presented as a model in . Key aspects of the process of interest development were identified. Each key aspect of the process of interest development, social interaction; curiosity; cognitive category; emotive category; extrinsic and intrinsic motivation; authentic interest; awareness, exploration, and new knowledge; a positive cycle of learning; and cognitive and emotional development, will be addressed in turn in the discussion.

Discussion

Social interaction

It was evident from the research that social interaction was key to developing interest. Social interaction in the form of teacher–child interactions; peer interactions; and parent–child interactions formed the basis of developing interest in the various topics of the enrichment program. Children’s knowledge is constructed through social and cultural experiences with teachers, family, friends, and others (Queensland Studies Authority [QSA], Citation2006).

Teacher–child interactions: Via social interaction between the teacher and the children, each component of the program was delivered through images, interesting facts, stories, music, and drama. Engagement increased as the teacher showed more enthusiasm and modelled curiosity. It soon became clear that the teacher did not know all the answers to the questions as children’s interest grew in a variety of directions. For example, the topic of birds led to questions about their nesting habits and eggs. The teacher became a learning partner, motivated to research the topic further. Learning is a social and interactive experience during which the children are in a relationship with the educator, characterized by scaffolding reciprocal teaching and imitation (QSA, Citation2006).

Parent/family-child interactions: Familial involvement was identified as another factor impacting curiosity and interest development in a positive way. Children were given take-home activity booklets on the various topics that they could complete with their families, for example an activity booklet where they had to collect leaves, bark, or seeds of trees. Parental feedback about the activity booklets, via questionnaires, was overwhelmingly positive with parents indicating that the information and activities in the booklets invited the family to be a part of the conversation and share in real-life experiences with the child. According to Joy et al. (Citation2021) parents can encourage their children’s learning through observations by providing some science explanations and by encouraging children to ask questions or explain concepts.

Peer interactions: Curiosity and interest were observed to be further stimulated by interactions between the children. Kamii (Citation2000) points out that young children rely not only on physical and logico-mathematical knowledge, but also on social knowledge. The children created artefacts, played fantasy games, bounced ideas off each other, solved problems and explored nature together. They brought in their completed take-home activity booklets, to share with the class as well as any ‘treasures’ they had found such as a feather, a flower, a leaf, etc. which stimulated conversation.

The finding that social interaction formed the basis of building interest is supported by sociocultural theory (Vygotsky, Citation1978) that stresses the important role that social interaction with parents, peers, and the community plays in learning as well as the view that learning is a social and interactive experience. Kuhl et al., (Citation2019) also stress the importance of social interaction in learning, claiming that young children benefit from strong, nurturing relationships with adults that encourage them to be curious about the world around them.

Curiosity in this study was generated via social interaction, the active ingredient (MCEETYA, Citation2008) in the process, connecting with the constructivist view that learning is a social and interactive experience (Schunk, Citation2008). Social interaction formed the basis of the model of interest develop as it facilitated curiosity and interest development.

Curiosity

Although young children are viewed as naturally curious and inclined to engage in the knowledge-acquisition process (Murayama et al., Citation2019), curiosity needs a spark, something that piques interest. Curiosity requires a trigger to grab the attention of the children utilizing features of novelty, ambiguity, and surprise to catch the child’s attention (Renninger & Hidi, Citation2016). Dewey (Citation1913) proposed that capturing interest begins with seizing attention and capturing imagination. In this research, the enrichment programs deliberately provided a spark for curiosity to develop into interest. For example, to generate curiosity about flowers, large realistic images of flowers were shown to the children, an interesting fact about each flower was shared and the children were provided with authentic flowers that they could engage with. The colours, smell, and feeling of real flowers, combined with music, movement and narrative provided a multi-sensory experience. Curiosity was further cultivated by providing cultural and natural objects within a play-rich environment that provided play provocations and real-life experiences and take-home activity booklets that encouraged parental engagement thereby facilitating the cognitive and emotional development. Curiosity is therefore considered to be is an integral part of the process of authentic interest development in this research as it facilitated knowledge (cognitive category) and emotions (emotive category) about the topic.

Cognitive category

Each program explicitly introduced the children to the language of that topic: terminology and concepts within the topic; building word banks and extending comprehension. Concepts and terminology were intentionally taught providing a cognitive category for interest development. For example, in the flower topic, the names of some flowers, an interesting fact about each flower and basic concepts and understandings such as what flowers need to grow, were shared with the children. As children develop language, they build a symbolic system, cultural tools helping them to understand the world (Vygotsky, Citation1978). It was observed how gaining the language of the topic empowered the children, allowing them to share ideas and thoughts and negotiate meaning. Language has a social function initially, providing a means for interacting with others, but as language skills increase, it begins to serve an intellectual function, a tool for problem-solving and self-regulation and a powerful mental tool (Vygotsky, Citation1978).

The children were tested on their knowledge of each topic before the topic was introduced. Some children had very little knowledge of the topic beforehand. It can be postulated that without knowledge, interest is impossible as a child cannot be interested in something if they are oblivious of its existence. The children were tested again two weeks later, after completion of the topic. The test results affirmed that all children gained knowledge from the enrichment programs, including a basic concept of the topic and increased vocabulary. Knowledge gained was utilized as an indicator of cognitive engagement. A cognitive category, knowledge of a topic and the language to communicate about a topic, was identified as a key part of authentic interest development.

Emotive category

Emotional engagement with each topic of interest was encouraged by inspiring a sense of wonder and awe, sometimes evoking empathy and compassion or a feeling of joy and delight. Some topics lent them to experiencing the wonder and awe of nature, some to feeling empathy or compassion for animals, or some simply the joy of seeing something delightful. According to Zakrzewski (Citation2012), awe is a powerful positive emotion that helps children focus less on themselves and more on the world around them as they lose awareness of ‘self’ and feel more connected to the world around them. A central message of compassion was integral to the programs promoting a sense of connectedness to people, animals, and the world. Addressing the basic psychological need to feel emotionally connected and close to others (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000) contributes to emotional development.

Difficult emotions such as the distress of seeing a video of an entangled whale freed from fishing nets were not avoided but addressed. They were given a safe space to explore their emotions via discussion that helped to build their vocabulary of emotions. Building children’s vocabulary of emotions will help them manage their emotions as they are also likely to have a greater knowledge of emotional regulation strategies (Streubel et al., Citation2020). They were also given the opportunity to process their emotions via music, art, drama (role-play) and free play, which contributed to emotional development.

It became evident in the research that the emotive category is closely linked to the cognitive category as the children asked more questions and wanted more information about the topics that engaged them emotionally. According to Trentacosta and Izard (Citation2007) the development of emotions occurs in conjunction with cognitive and behavioural development. In this research the indicators for emotional engagement were facial expressions, verbalisations, and body language. A lack of emotional engagement was used as an indicator that the program content had to be revised to make it more emotionally engaging in the following session. Hardiman (Citation2003) points out that connecting the learning with the child's emotions is an effective way to enhance attention, as emotions can have a profound effect on how information is processed and stored.

Neuroscience is now providing further evidence of the interrelatedness of emotion and cognition (Immordino-Yang, Citation2015). Nagel (Citation2013) states that emotions influence learning as it is neurobiologically impossible to build memories, engage complex thoughts, or make meaningful decisions without emotion. Emotions play an integral part in learning given that we typically recall things that have the greatest emotional impact, that separating thoughts and emotions is arguably impossible, and that learning that invokes a strong emotional response is more likely to be remembered (Nagel, Citation2013). An emotive category, experiencing a sense of wonder and awe, feeling empathy and compassion or mere joy and delight, was identified as a key part of authentic interest development.

From extrinsic to intrinsic motivation

In this research, children were initially extrinsically motivated by the educator who introduced the topic and modelled curiosity and interest. Nagel and Scholes (Citation2016) describe extrinsic motivation as a type of motivation that is facilitated by using external rewards. The extrinsic incentives used in this study were not physical rewards, but incentives in the form of social interaction with the educator who engaged the children with large realistic visually appealing images, interesting facts, stories, music, art activities and opportunities for real-life explorations and challenges. Murayama et al. (Citation2019) state that extrinsic incentives can be used to initiate information-seeking behaviour. As their interest in the topic grew, it was observed in the research that many of the children became more intrinsically motivated, i.e. no longer dependent on the extrinsic incentives. Nagel and Scholes (Citation2016) describe intrinsic motivation as motivation that is the product of an internal state or desire such as excitement or curiosity. The children showed spontaneous curiosity and began to experiment and seek information without external encouragement. Ryan and Deci (Citation2000) describe an intrinsically motivated person as one moved to act for the fun or challenge rather than because of external prods, pressures, or rewards, exploring a topic because it as an opportunity to learn something and there is great enjoyment in that. Barish (Citation2012) points out that interest is motivational as it leads to exploration and learning.

Pink (Citation2009) states that what motivates is intrinsic motivation, the deeply human need to direct our own lives, to learn and create new things, and to improve ourselves and our world. As the level of curiosity and interest increased in a topic, the children became more intrinsically motivated to explore and discover. It was noticed that they increasingly began to exercise their own will, making choices regarding what the theme of their play would be, linking to the concept of agency. Borg and Sameulsson (Citation2022) refer to children’s agency as the ability to make decisions regarding all aspects of their lives, including their learning and the ability to think, reflect and take a stand. Interest itself becomes a motivational force as it moves from being extrinsically motivated to being intrinsically motivated.

Initially, the children were extrinsically motivated by the educator to take part in the program and in the art-based activities, but as they became interested in the topic, their actions became progressively intrinsically motivated as indicated by their actions, questions, experimentation and play themes. The progress from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation is regarded as key to understanding in the development of authentic interest.

What is authentic interest?

The shift from curiosity to sustained interest is known as authentic interest in this study. Authentic interest is described as consisting of the two key conceptual categories described: a cognitive and an emotive category, with the implication that authentic interest requires both knowledge and emotion. Authentic interest is further described as being intrinsically driven; therefore, authentic interest is described in this research as an intrinsically motivated cognitive-emotive cognitive category.

The cognitive category consists of knowledge and understanding. A basic vocabulary and understanding of concepts provide the children with the language to start sharing ideas about the topic. The emotive category consists of emotions ranging from a sense of wonder and awe to compassion and kindness which gives the topic value. This connects to Paul’s (Citation2013) description of interest as knowledge emotion, both a cognitive and affective state.

Intrinsically motivated cognitive-emotive interest can be compared to schemata, or units of knowledge, within which knowledge is stored. Modern schema theory (Rumelhart et al., Citation1980) states that all knowledge is organized into units or schemata, creating a cognitive framework that helps organize and interpret information. The concept of a cognitive-emotive category differs from a schema as a cognitive-emotive category implies knowledge as well as emotion. Therefore, an individual may have a schema, but that schema does not necessarily imply that the individual is intrinsically or authentically interested in the topic. For example, an individual can have knowledge about a topic but may lack interest in it. However, having a schema or some form of knowledge is a key aspect of a cognitive-emotive category, as it is impossible to develop interest without knowledge.

As the children in the research became authentically interested in a topic, it was observed that their awareness of the topic increased as well as their eagerness to independently explore the topic through play. Raised awareness and exploration, leading to new knowledge, were seen as further indicators of authentic interest in a topic.

Awareness, exploration, and new knowledge

It became apparent that authentic interest is a motivational force leading to raised awareness, exploration, and learning. This behaviour was observed within every topic that the children were introduced to, from Arachnids to Structures. For example: the teacher reported how the children were talking about spiders and actively looking for spiders and webs and a mother said how excited her child was when she spotted a picture of the Eiffel tower. Had she not learned about the Eiffel tower she would probably not have noticed it, but now it brought her joy to spot it and she had the vocabulary to share her experience.

With authentic interest generated in a topic, awareness and exploration of the topic was facilitated. A child with heightened curiosity and interest has an enhanced sense of awareness potentially leading to exploration and learning, thereby connecting to the behavioural component of interest. Awareness increases the capacity of new knowledge and cognitive development, creating a positive cycle of learning.

Cycle of learning

The interest generated led to raised awareness, exploration, and new knowledge, created a cycle of learning, a cycle of repeated engagement with the topic. Mugan (Citation2014) describes a curiosity cycle where individuals uncover new insights or information that satisfies their curiosity and answers their questions. Silvia (Citation2006) refers to a virtuous cycle stating that the more we know about a topic, the more interesting it becomes. According to Silvia (Citation2006), learning leads to questions being asked which in turn leads to more learning. A positive cycle of learning relates to Vygotsky’s (Citation2004) culture of learning, an environment in which questioning and seeking answers are embedded.

Key to understanding the cycle of learning is that authentic interest cannot begin without knowledge. Quintero (Citation2017) advocates teaching rich and challenging content, as knowledge is the foundation for acquiring more knowledge. Leslie (Citation2014) states that curiosity and creativity are not killed by facts; the opposite is true as the more children know, the more they want to know, and more connections are made between different bits of knowledge generating more ideas, the wellspring of creativity. According to Hirsch (Citation2015), knowledge grows exponentially: the more one knows, the easier it is to learn new things. Adams (Citation2015) supports this view saying that students with more topic-relevant knowledge understand more, learn more, are more critical of information, make better inferences, and can apply their knowledge better. The opposite effect of the learning circle is also inevitable. Hirsch (Citation2015) refers to the effect of accumulated advantage saying that children who do not have topic-relevant knowledge fall further behind.

Cognitive and emotional development

From a developmental perspective, authentic interest enhanced cognitive and emotional development. Each cognitive-emotive conceptual category provided the children with ideas (knowledge) and feelings (emotion) regarding a specific topic. Therefore, this research suggests that the more topics a child is interested in, the greater the scope of conceptual categories contributing to the child’s ideas and feelings regarding the world. Establishing many conceptual categories contributes to a child’s network of knowledge (Lima, Citation2015), a network of knowledge that helps children to understand and navigate the world.

Implications for educators

The emergent model of interest development maintains that curiosity is sparked by social interaction, echoing the importance of educator and parental involvement in providing extrinsic motivations in the early years. Cognitive abilities are socially guided and constructed according to Vygotsky (Citation1978). This implies that the onus rests on educators, both teachers and parents to find ways to embrace children’s curiosity and interest by modelling interest and by intentionally sharing information that promotes cognitive development and emotive information that promotes emotional development.

Secondly, the model suggests that knowledge acquisition is key to developing authentic interest, thereby stressing the importance of intentionally providing children with the terminology and basic concepts that will allow them to share ideas and thoughts on specific topics, thereby supporting cognitive development. Unfortunately, educational systems are moving away from knowledge acquisition and shifting curricula towards skills acquisition (Bazinas, Citation2018). This model of interest development is a reminder that knowledge matters. From this model it is evident that knowledge is key to building interest. It is important that educators are successful in delivering content in the early years. Neglecting the presentation of interesting information to children and a content-rich curriculum puts interest development at risk. The value of knowledge acquisition should not be replaced by a skills development focus, but a balance between knowledge and skill acquisition is recommended.

Thirdly, the model suggests that authentic interest is supported by the emotive component. By connecting to personal emotions, through experiences of wonder and awe, empathy and compassion or simple joy and delight, children learn to care about the topic, increasing the value of the topic, enhancing their sense of connectivity, and supporting emotional development. Educators will therefore enhance interest development by facilitating knowledge acquisition as well as emotional acquisition.

Lastly, the model of authentic interest development confirms the value of promoting authentic interest development in a broad range of topics as a greater scope of conceptual categories provides a larger network of knowledge from which the child can navigate the world. The implication is that young children must be exposed to a broad range of topics with rich and challenging content that deliberately teaches terminology, basic concepts, empathy, and compassion, laying the foundation for the growth of authentic interest and stimulating cognitive and emotional development.

Conclusion

This study set out to explore how interest develops and to provide an emergent model of the process of authentic interest development from the analysis of the data. The key elements of authentic interest were identified and connected and the positive implications of authentic interest, namely raised awareness, exploration, and new knowledge creating a cycle of learning were conceptualised. Conceptualising the process of authentic interest development provides insights that have implications for early childhood educators. This paper argues that interest is key to cognitive development as it promotes learning through raised awareness and exploration leading to discoveries and new knowledge. Interest development should be promoted in the early years, a time when young children, in a sensitive period for learning, show natural curiosity. Educators can leverage authentic interest to effectively enhance cognitive and emotional development and create a culture of learning with young children. Parents and teachers must respond to this knowledge by re-evaluating the importance of interest, making interest development through knowledge acquisition as well as emotional acquisition a priority.

This theoretical model makes a conceptual contribution to knowledge in the field of interest development and provides a foundational step towards understanding the value of developing authentic interest in the early years.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ellie Christoffina van Aswegen

Dr Christa van Aswegen is lecturer at Griffith University. She has a background in psychology, early childhood education, gifted education, and internationalisation in early childhood education.

Donna Pendergast

Professor Donna Pendergast is Director of Engagement in the Arts, Education and Law Group at Griffith University. Her research expertise is education transformation and efficacy, with a focus on middle year’s education and student engagement; initial and professional teacher education; and school reform.

References

- Adams, M. J. (2015). Preface: Knowledge for literacy. In Albert Shanker Institute, American Federation of Teachers, and Core Knowledge Foundation, Literacy ladders: Increasing young children’s language, knowledge, and reading comprehension (pp. 4–10). Retrieved September 1, 2022 from https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=http://www.shankerinstitute.org/sites/shanker/files/Literacy%2520Ladders%25202015.pdf.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016). Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas. Retrieved September 1, 2022 from https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/seifa.

- Barish, K. (2012). Pride and joy. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bazinas, E. (2018). How to reorientate education from knowledge acquisition to knowledge & skill mastery. Retrieved September 1, 2022 from https://blog.100mentors.com/how-to-reorientate-education-from-knowledge-acquisition-to-knowledge-skill-mastery/.

- Bentley, R. (2000). Curriculum development and process in mainstream classrooms. In M. J. Stopper (Ed.), Meeting the social and emotional needs of gifted and talented children (pp. 12–36). London: David Fulton Publishers.

- Bodrova, H. (2003). Vygotsky and Montessori: One dream, two visions. Montessori Life, 15(1), 30–33.

- Borg, F., & Sameulsson, I. P. (2022). Preschool children’s agency in education for sustainability: the case of Sweden. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, https://doi-org.libraryproxy.griffith.edu.au/10.1080/1350293X.2022.2026439

- Collins, A. (1992). Towards a design science of education. In E. Scanlon, & T. O’Shea (Eds.), New directions in educational technology (pp. 15–22). Berlin: Springer.

- Council for Early Child Development. (2010). The science of early childhood. Retrieved 4 June, 2022 from http://www.councilecd.ca/files/Brochure_Science_of_ECD_June%202010.pdf.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The "what" and "Why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Dewey, J. (1913). Interest and effort in education. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Doidge, N. (2010). The brain that changes itself (2nd ed.). Carlton North: Scribe Publications.

- Fredericks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74, 59–109.

- Fuhrmann, L., Knoll, L. J., & Blakemore, S. (2015). Adolescence as a sensitive period of brain development. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(10), 558–566.

- Gibbs, R., & Poskitt, J. (2010). Student engagement in the middle years of schooling (Years 7-10): A literature review. Report to the ministry of education. New Zealand: Ministry of Education.

- Harackiewicz, J. M., Smith, J. L., & Priniski, S. J. (2016). Interest Matters. The importance of promoting interest in Education. Policy insights from the behavioural and brain sciences (2372–7322), 3(2), p. 220. doi:10.1177/2372732216655542

- Hardiman, M. M. (2003). Connecting brain research with effective teaching: The brain-targeted teaching model. Lanham: Scarecrow Press.

- Hirsch, E. D. (2015). Building knowledge. The case for bringing content into the language arts block and for a knowledge-rich curriculum core for all children. In Albert Shanker Institute, American Federation of Teachers, and Core Knowledge Foundation, Literacy Ladders: Increasing Young Children’s Language, Knowledge, and Reading Comprehension (pp. 30–41). Retrieved 4 June, 2022 from https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=http://www.shankerinstitute.org/sites/shanker/files/Literacy%2520Ladders%25202015.pdf.

- Immordino-Yang, M. H. (2015). Emotions, learning, and the brain: Exploring the educational implication of affective neuroscience. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

- Joy, A., Law, F., McGuire, L., Mathews, C., Hartstone-Rose, A., Winterbottom, M., … Mulvey, K. L. (2021). Understanding parents’ roles in children’s learning and engagement in informal science learning sites. Frontiers in Psychology, 12), doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635839

- Kamii, C. (2000). Young children reinvent arithmetic: Implications of Piaget's theory. New York, NY: Teacher's College Press.

- Kuhl, P., Lim, S., Guerriero, S., & van Damme, D. (2019). Neuroscience and education: How early brain development affects school, in Developing minds in the digital age: Towards a Science of learning for 21st century education. Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved 4 June, 2022 from https://ilabs.uw.edu/sites/default/files/19Meltzoff_Cvencek_STEMIdentity_OECD.pdf.

- Leslie, I. (2014). Curious. The desire to know and why your future depends on it. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Lima, M. (2015). A visual history of human knowledge [Video file]. Retrieved 4 June, 2022 from http://www.ted.com/talks/manuel_lima_a_visual_history_of_human_knowledge/transcript?language=en.

- Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA). (2008). Melbourne declaration on educational goals for young Australians. Retrieved 4 June, 2022 from http://www.mceetya.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf.

- Mugan, J. (2014). The Curiosity Cycle: Preparing your child for ongoing technological explosion. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Murayama, K., Fitzgibbon, L., & Sakaki, M. (2019). Process account of curiosity and interest: A reward-learning perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 31, 875–895.

- Nagel, M. C. (2013). Understanding and motivating students. In Churchill, R., Ferguson, P., Godinho, S., Johnson, N.F., Keddie, A., Letts, W., Mackay, J., McGill, M., Moss, J., Nagel, M., Nicholson, P., Vick, M. Teaching: Making a difference (2nd ed.) (pp. 112–143). Brisbane: John Wiley & Sons.

- Nagel, M. C., & Scholes, L. (2016). Understanding development and learning implications for teaching. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Paul, A. M. (2013). How the power of interest drives learning. Mind Shift Public Media for Northern California. Retrieved 4 June 2022 from: http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/2013/11/04/how-the-power-of-interest-drives-learning/.

- Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive. New York, NY: Riverhead Books.

- Prime Minister’s Science Engineering and Innovation Council. (2009). Transforming learning and the transmission of knowledge. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Queensland Studies Authority. (2006). Early years curriculum guidelines. Retrieved 4 June, 2022 from https://www.qcaa.qld.edu.au/downloads/p_10/ey_cg_06.pdf.

- Quintero, E. (2017). Teaching in context: The social side of education reform. London: Harvard Education Press.

- Renninger, K. A., & Hidi, S. (2016). The power of interest for motivation and engagement. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Rumelhart, D. E., et al. (1980). Schemata: The building blocks of cognition. In R. J. Spiro (Ed.), Theoretical issues in Reading comprehension (pp. 33–58). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

- Schunk, D. H. (2008). Learning theories: An educational perspective (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

- Silvia, P. J. (2006). Exploring the psychology of interest. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Streubel, B., Gunzenhauser, C., Grosse, G., & Saalbach, H. (2020). Emotion-specific vocabulary and its contribution to emotion understanding in 4- to 9-year-old children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 193, 104790.

- Trentacosta, C. J., & Izard, C. E. (2007). Kindergarten children's emotion competence as a predictor of their academic competence in first grade. Retrieved 11 June 2022 from file:///C:/Users/home/Downloads/RNESDemot2007Kto1st.pdf.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (2004). Imagination and creativity in childhood. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 42(1), 7–97. doi:10.1080/10610405.2004.11059210

- Zakrzewski, V. (2012). An awesome way to make kids less self-absorbed. Retrieved 4 June 2022 from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/an_awesome_way_to_make_kids_less_self_absorbed#.