ABSTRACT

This study aims to examine preschool literacy practices during observations in Swedish preschools with a focus on environment, read-alouds and emergent writing. The study reported on in this article is based on empirical data from 433 observations in preschools in 80 Swedish municipalities that has been analysed qualitatively and quantitatively. Descriptive analyses have been performed on the quantitative data, and observation notes have been coded and thematically analysed. Five themes were created in the thematic analysis of the qualitative data: differences in accessibility to books, few books in different languages, differences regarding existing reading events, read aloud to calm children, and few existing writing events. The study constitutes an essential basis for knowledge, as well as a prerequisite for future intervention studies and the development of relevant in-service education for preschool teachers. Our conclusion is that there is a considerable lack of equity regarding literacy environments in Swedish preschools.

Introduction

Preschools have a unique opportunity to even out unequal opportunities for language and literacy development. In Sweden, 86 per cent of all children aged one to five are enrolled in preschool with a curriculum emphasizing play as major tool for learning, in contradiction to the formal tuition characterizing school practices for children aged six years or older (The Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2022). Thus, preschools constitute an important basis for a more equitable language and literacy development. Preschools can ensure that all children start school with more equal opportunities, regardless of their home environment, as some children do not grow up in homes with literary cuddling, such as bed time stories, as cultural patterns do diverge across different parts of the world (Salameh, Citation2018). However, research on the quality of Swedish preschools (Sheridan, Williams, & Garvis, Citation2020) and evaluation reports (SOU, Citation2020; Swedish School Inspectorate, Citation2018) have revealed variations in the quality of literacy environments for children in preschool, which can impact opportunities for literacy development and how preschools’ compensatory mission is carried out.

Given the above, this article's searchlight is directed toward Swedish preschools and the conditions for emergent literacy events. Emergent literacy events include oral language skills such as speaking and listening, children's understanding of how print transfers meaning, and familiarity with print. These literacy events constitute the way children build linguistic awareness before reading and writing skills are established (Lonigan, Faver, Phillips, & Clancy-Menchetti, Citation2011; Norling, Citation2015). Reading and listening to stories creates widened frames of reference. The use of shared book reading as an important step in lifelong learning is therefore in line with the definition of literacy presented by UNESCO, which describes literacy as a part of ‘a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and broader society’ (UNESCO, Citation2017).

One contributor to emergent literacy is read-aloud time. Hence, the article has a particular focus on read-alouds and shared book reading in preschool as a means to promote language and emergent literacy development. Read-alouds promote language development for first-language learners, particularly dual-language learners (Grøver, Rydland, Gustafsson, & Snow, Citation2020). A second condition for developing emergent literacy is access to books for spontaneous reading. Thus, the article's second focus is children's access to books in preschools. The amount and types of books children have access to can be seen as a marker of the extent to which preschools encourage and stimulate emergent literacy (Guo, Justice, Kaderavek, & McGinty, Citation2012; Hofslundsengen et al., Citation2020). The third condition targeted in the article is emergent writing activities, since early writing in preschools has been shown to have a positive impact on later literacy development (Bingham, Quinn, & Gerde, Citation2017; Gerde, Bingham, & Pendergast, Citation2015; Hall, Simpson, Guo, & Wang, Citation2015; Hofslundsengen, Hagtvet, & Gustafsson, Citation2016).

Children have different early experiences of reading and writing, different socio-economic backgrounds, and enter preschool at different stages of language development (Aldén & Hammarstedt, Citation2016; Liberg, Hultin, Lundgren, & Olin-Scheller, Citation2015; Schmidt, Citation2018; SOU, Citation2020:46). In a society that is often described as increasingly unequal and segregated, the preschool’s mission to work towards greater equity is perhaps more important than ever. In 2020, a state inquiry was initiated to explore how enrollment in preschool can be increased, which led to a bill in 2022 aimed at ensuring that all caregivers are contacted and offered enrollment in preschool as part of the mission to strengthen the position of the Swedish language in preschool (SOU, Citation2020, p. 67). In 2023, all caregivers will be contacted and offered a space for their child in preschool, and the position of the Swedish language shall be strengthened in preschools (Swedish Government, Citation2022).

An unequitable preschool system can reinforce existing segregation and inequality (Persson, Citation2015). The Swedish Education Act (SFS, Citation2010:Citation800), which provides a framework for preschool activities in Sweden, states: ‘Children must have equal access to education, equal quality in education together with preschool's compensatory mission to provide adjusted learning conditions for all children’. According to the curriculum for preschool in Sweden, ‘Children should be offered a stimulating environment where they are given the opportunity to develop their language by listening to reading aloud and discussing literature and other texts’. (The Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2018, p. 9) Regarding literacy, the curriculum states:

The preschool should provide each child with the conditions to develop an interest in stories, pictures and texts in different media, both digital and other, and their ability to use, interpret, question and discuss them; a nuanced use of spoken language and vocabulary, as well as the ability to play with words, relate things, express thoughts, ask questions, put forward arguments and communicate with others in different contexts and for different purposes; an interest in the written language and an understanding of symbols and how they are used to convey messages. (The Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2018, pp. 14–15)

Moreover, preschools have an increased proportion of staff without a preschool teacher education. The Swedish National Agency for Education (Citation2021) reported that just over 40 per cent of preschool staff in Sweden have a preschool teacher degree. The proportion of staff without a preschool teacher degree is higher in large cities.

As mentioned above, since children have different conditions for the development of literacy in the home environment (Aldén & Hammarstedt, Citation2016; Schmidt, Citation2018), it is vital that preschools offer rich literacy environments that include availability to books (Hofslundsengen et al., Citation2020), read-aloud activities, and writing activities (Grøver et al., Citation2020; Hall et al., Citation2015). To explore these conditions, the following aim and research questions have been formulated:

This study aims to examine existing preschool literacy practices through observations in Swedish preschools, focusing on the environment, read-alouds, and emergent writing.

RQ:

What are the prerequisites for reading in the preschool literacy environment?

What reading and writing activities occur, and how are these performed?

How often do reading and writing activities occur?

Theoretical point of departure

In this article, literacy is seen as a social practice (Barton, Hamilton, & Ivanic, Citation2001) that can be used to clarify the link between different literacy activities, such as reading and writing, and the social context surrounding and shaping the activities (Barton, Citation2001). Literacy practices can be defined as cultural ways of utilizing literacy and are shaped by social values and unwritten rules, which impact how texts are used and who has access to them (Barton et al., Citation2001). Cultural ways of utilizing literacy are difficult to observe. However, what can be observed are literacy events. Literacy events are activities where literacy has a role; for example, reading, writing, talking about texts, or other activities that involve texts. Evidently, ‘writing’ with 3-year-olds should be understood as pre-writing as means for children to build on to their language awareness, which much differs from formal writing tuition. Pre-writing, when children laborate with self-made signs and symbols is rather to be seen as an exploration of written language a a symbolic system, where it may take several years before the child understands that it is only by use of the conventional alphabet the ‘text’ may communicate to other readers (Liberg et al., Citation2015). These events are observable, are shaped by literacy practices and emerge from these practices. In all literacy events, texts constitute a crucial part of the activity.

In this article, we observed and identified literacy events with a particular focus on prerequisites for reading in the preschool's literacy environment and existing reading and writing activities.

Previous research

Research has shown that the conditions for children to develop language and literacy varies in Swedish preschools. For example, a recent study by Nasiopoulou, Mellgren, Sheridan, and Pi (Citation2022), which explored the conditions for language and literacy learning in 153 Swedish preschools, found statistically significant differences and unequal conditions for language and literacy development. The researchers found that, on average, oral language activities achieved higher quality scores in the studied preschools, while book reading, and other print activities scored lower. The preschool’s physical environment can be seen as an indicator of the quality of the preschool and the type of education the teachers prioritize. Books, writing materials, and other printed materials are items that, are valid markers of preschool environments with the potential to stimulate emergent literacy (Dynia et al., Citation2018; Hofslundsengen et al., Citation2020). In line with this, Guo et al. (Citation2012) have shown that a relationship exists between the physical literacy environment and the extent to which a teacher encourages the children's literacy development. Furthermore, results from the same study revealed that the physical literacy environment was crucial for children's writing exploitation (Guo et al., Citation2012).

Read-alouds have been shown to be the most common literacy activity in preschools in northern countries, but there is great variation in the conditions for reading aloud, what is read, why the text is chosen, and how often it is read (Alatalo et al., Citation2022). Even though teachers acknowledge that read-alouds are important, their efforts to include read-alouds do not always succeed due to logistical and practical challenges (Alatalo & Westlund, Citation2021). Preschool teachers’ perceptions of read-alouds in Swedish preschools were studied by Alatalo and Westlund (Citation2021). External factors, such as large groups and the requirement to teach math and science, are seen as obstacles to the planning and implementation of read-alouds. However, teachers who have received in-service training and professional development report that they conduct daily read-alouds followed by text talk (Alatalo & Westlund, Citation2021).

Reading as a means to provide rest time is a common practice in Swedish preschools (Damber Citation2015). Damber (Citation2015) and Damber and Nilsson (Citation2015) show that reading is mainly used to create a calm atmosphere in Swedish preschools. In parallel, spontaneous, and active reading and writing exploration occurs in preschools with an actual function. Through active reading, children can experience the joy and curiosity active reading sessions offer. The authors conclude that using reading as a disciplinary activity is a result of care traditions from previous decades. According to results from Damber (Citation2015) and Damber and Nilsson (Citation2015), two main factors contribute to spontaneous reading activities: easy access to books and children's familiarity with and high expectations of reading activities. In another study by Damber and Nilsson (Citation2015) where literacy activities in preschools were observed, results indicated that read-alouds generally occurred once a day, however, the activity was seldom embedded in a context or planned. Books were chosen randomly. Follow-up activities occurred in 27 per cent of the reading occasions observed. Thus, Damber and Nilsson (Citation2015) concluded that read-alouds primarily had a disciplinary focus.

Research shows that reading contributes positively to language development in multilingual children (Grøver et al., Citation2020). Active dialogic read-alouds build on an array of connected factors, enhancing language and emergent literacy skills. Children can build on the first language to further advance their learning in a second language, in this case, Swedish. One vital characteristic of effective read-alouds is that children are not read to but read with, thus emphasizing the dialogue in connection to read-alouds. In this activity, open questions play an essential role in stimulating children to interpret the text and make conclusions, thus comparing the text with their own and other children's experiences, other texts, and the surrounding world (Dowdall et al., Citation2020).

Vocabulary stands out as means to develop rich language skills, in turn enhancing future academic success. In this respect, shared story reading has the potential to present more unfamiliar words to the children, where the context of a story supports the children's understanding, as vocabulary is not only a question of the number of words, but also the build-up of semantic schemes (Hart & Risley, Citation1995; Salameh, Citation2018). In addition, children's stories tap into knowledge about the world and how different settings and dilemmas may be experienced by others, thus providing emotional and reflective experiences (Dowdall et al., Citation2020). In a Norwegian quantitative preschool study with more than 450 participants, multilingual children developed both first and second language skills when they participated in reading activities where teachers talked about different words and the book's narrative content. In addition to reading activities at the preschool, the study also carried out reading activities at home with the parents (Grøver et al., Citation2020). The study’s results revealed that shared book reading significantly improved young children's second language grammar and vocabulary skills.

Furthermore, research has shown that shared reading in the first language with second language children contributes to the development of second language vocabulary (Grøver et al., Citation2020; Hermanns, Citation2010; Lugo-Neris, Jackson, & Goldstein, Citation2010). Despite the proven benefits of encouraging first and second language learning, many preschools do not have books and other texts in the first language of bilingual preschoolers. In the study by Hofslundsengen et al. (Citation2020), as many as 82 per cent of all children were bilingual, however, books in first languages were rare.

In addition to reading, early writing activities in preschools have also been shown to have a positive impact on later literacy development (Bingham et al., Citation2017; Gerde et al., Citation2015; Hall et al., Citation2015; Hofslundsengen et al., Citation2016), where the promotion of writing through scaffolding and teaching can encourage children's reading and writing skills (Hofslundsengen et al., Citation2016). In the study by Hofslundsengen et al. (Citation2016), emergent literacy skills were examined among 105 preschool children after an intervention consisting of a writing program that included a broad set of writing activities. Compared to the control group (children who completed ordinary preschool activities), the children who participated in the writing program performed significantly better when measuring phoneme awareness, spelling, and word reading. However, the findings also indicate that writing activities are under-represented or non-existent, thus highlighting a gap in children's prerequisites for writing development (Bingham et al., Citation2017; Gerde, Wright, & Bingham, Citation2019; Guo et al., Citation2012; Hofslundsengen et al., Citation2020). The reasons writing activities are excluded in preschools can be that teachers perceive that young age and poor motor skills are barriers to writing (Gerde et al., Citation2019). Findings from a Nordic literacy project, where preschool teachers in Sweden and Norway were asked about reading and writing activities in preschool, revealed that writing is not used as frequently in toddler classrooms compared to classrooms for older children (Alatalo et al., Citation2022). In the study by Gerde et al. (Citation2019), which included observations on writing activities in preschool and interviews with preschool teachers, the findings indicate that preschool teachers believe that young children are also interested in writing activities. However, the results revealed a narrow focus on writing activities in preschool.

Although there are some studies on literacy activities in Swedish preschools, we only found limited studies that included a large number of participants. The present study provides a more comprehensive picture of the prerequisites for reading and writing, thus filling a gap in emergent literacy research.

Method

This study aimed to examine existing preschool literacy practices through observations in Swedish preschools, focusing on environment, read-alouds, and emergent writing. The study material is based on extensive observations in Swedish preschools, only including observations from the daily practice with no extra-curricular activities included. To achieve the aim of the study, a multiple method design was used (Morse, Citation2003) as two different methods, each conducted rigorously, were used to create a comprehensive whole from the data. That is, a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches has been used.

Instrument and data collection

Teacher education students at Mid Sweden University made the observations. This was a mandatory assignment in a course on reading and writing development. The students performed the observations over the course of an entire day in a preschool, using a protocol developed by the authors. Since preschool teacher education in Sweden is both an academic and practical education, the students are expected to learn about various scientific methods such as, for example, conducting observations. In previous courses students attended lectures and workshops concerning observation as a scientific method. A lesson was conducted with the students where we talked about what was essential to consider in this particular observation. Students had an opportunity to ask questions and discuss possibilities and shortcoming with the observations. The protocol contained multiple-choice questions, numeric questions, and open-ended questions. The protocol included numeric questions about, the age of the children, the number of fiction books in the preschool and also the number of books available to the children, number of books in other languages than Swedish, and amount of time spent on writing and reading activities, both independently and together in groups that took place during the day. The protocol also included open-ended questions about if and how preparatory writing activities were organized, reflections on reading and writing activities, and how the reading activities were organized. Finally, there were multiple-choice questions about genres, what activities that took place during read-alouds, and how the reading and writing activities were organized.

Both earlier research and our own research and recurring contacts with preschool-teacher students and preschool practices indicate the themes that are targeted in the observation protocol. The activities characterize preschool practices, but the frequency and the how they are carried out with respect to children’s development of emergent literacy and linguistic awareness vary across preschools. Factors, like where the preschool is located geographically, the number of educated preschool-teachers etc., have impact on the practices. Our study wanted to target this variability, as this is one of more studies to come, to study the development of preschool practices over time.

As all preschools have the same curriculum, the activities observed by the students always exist in the preschools. Our inquiries were directed toward how emergent literacy is interpreted in preschools, by observations of markers visible in the classroom environment and in activities.

The observations were made without collecting any names of teachers, children or preschools, in order to ensure confidentiality. Thus, some of the observations may have been performed at the same preschool during different days the same semester or during different semesters. For example, in two of the municipalities, we have a high number of observations, 80 and 65, respectively, some municipalities have 11–20 observations, and most of the municipalities have a single observation from one preschool.

The students submitted their observations in a digital observation protocol. In this way, the authors accessed data from 435 observations. The data collection occurred twice a year, with different students, during the period 2017–2020. A limitation is that the data only includes an observation of a single day in the majority of the preschools. It may be that the literacy practices would differ if the observation had taken place during another day. However, the large amount of observations gives an overview of literacy practices in preschools.

Participants

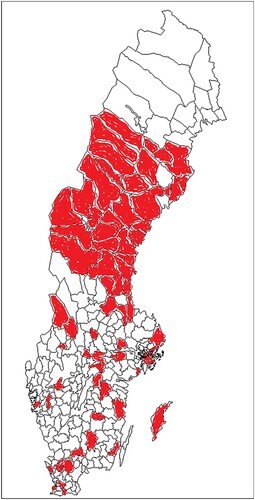

A total of 435 preschool observations were performed by all teacher education students that participated in a course given each semester during the period 2017–2020. The students were informed about the use of data in research and gave their consent. The data collection took place during the period 2017–2020 in 80 of the 290 municipalities in Sweden (see map in ). Contextual factors and resources differ between preschools. Official data on the proportion of staff that have a Swedish certification as a preschool teacher in each municipality shows a wide range, 22% through 71%, on average during the years 2017–2020, in our sample. The average was 41% and the standard deviation was 11,3. The certification is possible to get for those who have a university degree as preschool teachers.

Swedish preschools are often organized so that different age groups are separated into different premises. There is usually a group of younger children, aged one through three, and a group of older children, aged three through five. Some preschools have mixed age groups. As seen in , the majority of the observations took place in groups with children aged three to five.

Table 1. Number of and share of observations in preschools by age groups.

In , it can be noted that the observed preschools had three to four multilingual children on average. The variation is large and ranged from zero to 24 multilingual children in each observed preschool group.

Table 2. Mean, standard deviation, and range for the number of multilingual children in each preschool by age group.

Analysis

Initially, descriptive statistics were used to create an overall pattern of preschool literacy practices and resources. Stata 14.2 was used for these analyses (StataCorp., Citation2015). The observations were analysed by age group.

After completing the statistical analysis, we approached the open-ended questions qualitatively using thematic analysis according to Braun and Clarke (Citation2006).

Following Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), the analysis involved a constant movement back and forth between the raw data, the coded extracts and the results of the analysis. The analytical process involved ongoing reflection and discussion within the research group to ensure the reliability of the categorization and themes of the analysis. The analysis process is presented below:

Initially, in accordance with the analysis method, we familiarized ourselves with the data by reading through the observation and reflection protocols of all study groups.

The next step was to code all the material. In this phase, words and sentences related to our research questions were coded; for example, text where the students related to the literacy environment or literacy activities was highlighted and named to enhance categorization.

The third step involved the creation of preliminary themes based on the coded material. Relationships between codes were analysed and sorted into categories and preliminary themes were created. All codes regarding, for example, varied access to books formed a preliminary theme and codes concerning reading and writing that belonged to the school formed another preliminary theme.

We then tested and analysed the themes against our theoretical starting points and research questions and determined the final themes.

The last step was to write the results based on descriptive statistics and thematic analysis.

The whole analysis process was performed by all researchers together. The constructed themes were used as headings when writing the results section in the article.

Results

Access to children's books and picture books is a necessary condition for all literary work. Therefore, the number of books, accessibility to reading materials, and the use of tools to enable listening to stories in languages other than Swedish attracted our attention. Five themes were created in the thematic analysis: differences in accessibility to books, few books in different languages, differences regarding existing reading events, read aloud to calm students, and few existing writing events.

Differences in accessibility to books

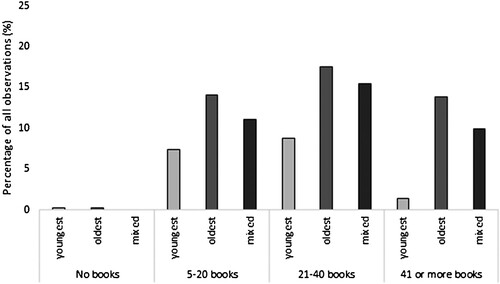

Almost all observations show that the preschools had printed books, which include both books available to the children and those only accessible to the teachers (see ). It was most common in all three age groups to have 21–40 books at the preschool. However, not all of these printed books are accessible to children.

Figure 2. The percentage of observations with printed books, and number of printed books, out of all observations.

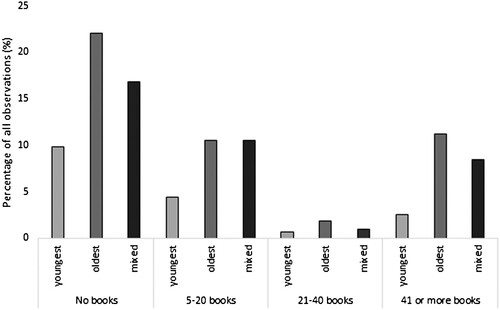

About half of the observations (49%) state that no books are available to the children (see ). In other words, 208 out of 427 observations indicate that no books are accessible to the children at the preschool. Surprisingly, that was the most common result for all three age groups.

Figure 3. The percentage of observations with accessible books, and number of printed books, out of all observations.

The way children access books varied across the preschools, as illustrated in . In some preschools, the books were accessible to the children as described in the following quotation, where books were found in all locations across the premises: ‘ … books of different genres were placed at a suitable height, so all the children could reach them. There were books in all the different languages, and for the different age groups’. However, low accessibility was more often reported in the observations: ‘ … books were thrown into a chest, inaccessible to the children’, or simply put in boxes where the content of the boxes was not visible. In this way, the value of stimulating children's curiosity about books is overlooked, thus signaling the value of literature in the preschool’s teaching practices.

The fact that physical contact with books plays a role in children's interest in reading is also reinforced in the observations with references to library visits and book buses: A close connection with librarians at the library or in a book bus is repeatedly mentioned in the context of children's interest in books and reading. In particular, a raised level of interest upon the arrival of the book bus was observed, as this event signifies access to new books and allows students to borrow books of their own choosing.

Few books in other languages

In 66 per cent of 433 observations, no books in languages other than Swedish were available. This should be considered in relation to the fact that in 76 per cent of the observations, at least one child at the preschool has a mother tongue other than Swedish. Moreover, the observations indicate that preschools with a high number of multilingual children have very few books in languages other than Swedish.

Many preschools have a high percentage of children with a mother tongue other than Swedish. Still, the overall impression of the observations is that children's books in languages other than Swedish are scarce. This was something noted by many of our observers, though the opposite scenario is also described: ‘ … they had books in different languages as there were many children that spoke another language than Swedish at home’. However, the following quote is more indicative of the typical observation: ‘There was not a single book in another language than Swedish, especially since 16 out of 20 children had another mother tongue than Swedish’.

However, ways to address the lack of reading material in other languages include the use of multilingual storybook apps and the use of QR-codes, which enable children to listen to books read in their mother tongue, though the children seem to have somewhat limited access to multilingual digital tools.

Differences regarding existing Reading events

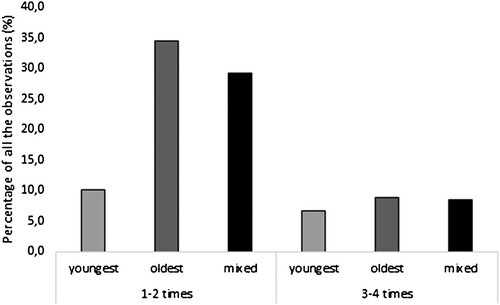

Among all of the observations where at least one read-aloud situation (n = 316) occurs, it was most common that read-aloud occurred in a group setting one time during the visit. For example, 48 per cent of the observations in groups of older children indicated one read-aloud occurrence during the day. shows the percentage of read-aloud events for the three age groups. In another open-ended question, students commented that no read-aloud occasions occurred in some of the 116 cases of non-responses. Read-alouds most often occurred when the children were about to sleep or rest during the day. The second most common occurrence was a scheduled time, and third, at times initiated by the children themselves. Fiction was the dominant genre. Read-alouds that included textbooks, factual texts, instructional texts, and poetry were reported only on a few occasions. The duration of the read-aloud was shorter for the youngest children, usually 10–20 min. The groups with older children and the mixed age groups often had longer read-alouds, about 20–40 min.

Figure 4. The percentage of observed read-alouds in the groups, and frequency, out of all observations.

In terms of fulfilling the demands in the curriculum that all children are to be introduced to different texts and engage in dialogs about content, read-aloud is the most significant means to achieve this end. Daily read-alouds have the power to engage children's intrinsic motivation to listen and ponder about what is happening in the fictitious worlds in children's literature. Therefore, the recurring observation, ‘There was no reading’, raises a red flag. The quality of the reading sessions also nurtured critical reflections among some of our observers:

It surprised me that only one reading event was planned during my day at the department. During this reading event, the educator gathered the whole group of children / … /, and after reading the story, the gathering was over. No dialogue neither before, during, nor after the read-aloud. She initiated no conversations, and the reading felt more like a sort of padding or fill-out.

I have been most concerned with the fact that reading and writing were so insignificant in practice. It was nothing the teachers planned for or prepared for.

In addition, spontaneous activities linked to reading are reported. In one preschool, cookbooks were used when the children were playing in the kitchen and these were read aloud to each other, thus allowing the children to engage in functional reading and make use of the context:

Several times during the day, several children were observed ‘reading’ aloud to each other, particularly in the kitchen, where recipes were read to explain how much flour was needed in the bowl, etc.

Spontaneous literacy activities and pretend reading were also observed in classrooms with young children, indicating substantial interest in reading:

Although the children were 1–2 years of age, they were interested in reading and listening to books. They were keen on reading on their own and took a lot of initiative to listen to a story ‘read’ by another child or to look at the pictures together.

Reading to calm students

Reading-rest, where reading is used as a calming activity after lunch, is another phenomenon that was observed. Read-alouds were restricted to reading-rest after lunch, serving more as a social skill activity than a learning activity, with the children expected to sit calm and quiet. One student reported that there were ongoing discussions regarding whether the time after lunch was the best time to read books, as some of the children were asleep. One student gave an example:

The reading sessions are usually in connection with a ‘reading rest’. The younger children thus sleep every time books are read in groups and therefore do not get the opportunity to have the same experiences as the older ones, even though it is essential to get this experience early.

Few existing writings events

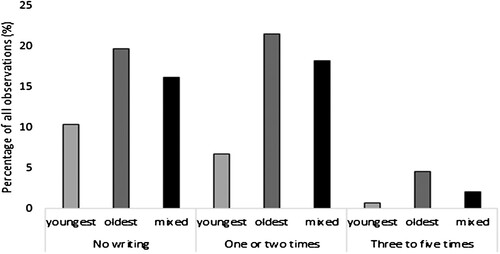

The students were asked to report the number of times writing in groups occurred during the day. Almost half of the observations (46%) did not indicate any writing in groups during the day of observation (see ). In the oldest group (n = 198) and the mixed groups (n = 158), writing occurred one or two times in 93 and 79 observations, respectively. About one third of the observations in the youngest groups indicated that writing took place one time during the visit at the preschool. The majority of observations showed that children wrote with pencils on paper (72%). Other tools were also used. For example, computer tablets (5%), smartboards, and clay were used during some of the observations. Scribbling was the most common text type.

Figure 5. Percentage of observations of a number of writing activities in groups out of all observations.

Many of the students declared that no writing at all occurred during their observations, with the primary explanation being that the children were perceived to be too young. shows that classrooms without any writing or with little writing dominated preschool classes with the younger children. This was also noted by the student observers. One student explained this phenomenon as: ‘there were no writing events, as the children are too young, according to the teachers at this preschool’.

On the other hand, it was also observed that the young children engaged in writing on their own initiative, for example, writing letters on their sandwiches with caviar:

When the children drew and pretended to write, they said they had written their names! The preschool teachers read letters (for example, letters on the sandwiches), so the children could learn them.

Interestingly, the older children's writing was contagious in groups of mixed ages, and the youngest children showed interest in written language. Most of the three-year-olds could write and read their names, names of family members, and names of their closest friends.

Planned writing activities were scarce, and as a whole, writing activities seem to have been left to the children themselves, as illustrated by the students’ remarks: ‘writing always happened on the children's initiative’, and ‘the writing occurred when the children were playing, without help from any teachers’. In the students’ observations, the most frequent writing activity involved children writing their names on pictures they had drawn.

Even though it was infrequent, observations confirm that writing activities involving both children and educators did occur. For example, one observation illustrates how the teacher wrote the children's account of a story on a whiteboard. Children were also observed to create books with drawings clipped from magazines:

The children cut out pictures from magazines, drew their pictures, wrote letters, and engaged in pretended writing, using images to illustrate what they had written.

These children show that they have built up linguistic confidence. I think it has to do with the fact that the educators are eager to engage the children in dialogues when they read to them, not only reading aloud, but also working with the story's content.

To conclude, the results show a substantial variation concerning children's prerequisites for literacy events in Swedish preschools. The variation involves children's access to books in Swedish and other languages and relevant reading events. In terms of writing events, the results indicate that writing is a lower priority than reading in Swedish preschools.

Discussion

The results presented in this article revealed that children have unequal opportunities for literacy development in Swedish preschools. There are large differences between the preschools observed in this study. As a consequence, there is a lack of equity in the conditions concerning emergent literacy events in Swedish preschools. As mentioned, preschools have an essential role in offering children with various backgrounds and experiences of literacy a rich literacy environment with opportunities to develop emergent literacy. When preschools provide unequal access to education opportunities, there is a risk that existing inequities will be reinforced for children in Swedish society (Persson, Citation2015). This is also described in the Education Act (SFS, Citation2010, p. 800), which stipulates that preschool must be based on three fundamental aspects: Children shall have equal access to, and equal quality in, education that also has a compensatory effect to offset differences in children's different conditions to assimilate education. Individual preschools or municipalities cannot decide to opt out this law Furthermore, this problem is targeted in the recently passed bill to increase enrollment in preschools and to strengthen the position of the Swedish language in preschools (Swedish Government, Citation2022). However, for the bill to have an impact on literacy development, Swedish preschools also need to become more equitable to ensure that the optimum conditions are created for language development. Moreover, it is not enough to strengthen the position of the Swedish language. As previous research demonstrates (Grøver et al., Citation2020), multilingual children benefit from the development of both of their languages. Literacy is described by UNESCO (Citation2017) as a part of ‘a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and broader society’. Therefore, preschools must offer rich literacy practices for all children (Aldén & Hammarstedt, Citation2016; Schmidt, Citation2018). The overall literacy environment includes rich literacy practices (Hofslundsengen et al., Citation2020), read-alouds, text talks, and writing activities (Grøver et al., Citation2020; Hall et al., Citation2015).

In the observations performed in this study, the availability of books varied significantly between preschools. As shown in the study by Guo et al. (Citation2012), the physical literacy environment and teachers’ promotion of children's literacy development are closely related, which may mean that children attending preschools without a strong literacy environment may have fewer opportunities to develop literacy skills. Furthermore, the results of the present study showed limited availability of books in languages other than Swedish, even in preschools with a high number of multilingual children. These results are in line with other studies in northern countries. For example, in a study conducted in the Nordic region by Hofslundsengen et al. (Citation2020), as many as 82 per cent of all children were bilingual in the preschools studied, but books in the first language were rare. Still, some observations revealed opposite conditions, where some preschools had rich literacy environments with many books in several languages and access to a variety of digital books. Here, we would like to reemphasize the prevailing inequality concerning conditions for literacy development for children in general, and bilingual children in particular, in Swedish preschools.

The availability of reading material also has an impact on read-alouds. Read-alouds support language development for first-language learners and are particularly important for dual language learners (Grøver et al., Citation2020).

Similar to the study by Alatalo et al. (Citation2022), the study that forms the basis for this article found a large variation in the conditions for reading aloud. In some preschools, read-alouds were common and were followed by joint activities to process the content of the readings. In other observations, most of the reading occurred on the children's initiative and was not always supported by teachers. Research has shown that teacher interaction and supportive activities, such as talking about words and the book's narrative content, promote first and second language development among multilingual children (Grøver et al., Citation2020).

Similar to the study by Alatalo and Westlund (Citation2021), our student observers reported that teachers found it challenging to make time for read-alouds given the other activities they needed to squeeze into their daily preschool practice. Furthermore, the results from this study indicate that read-alouds are still often used to soothe children or provide an opportunity for rest. As there is a large body of recent Nordic research on the importance of interactive read-aloud events in preschool (Damber & Nilsson, Citation2015; Damber, Citation2015; Grøver et al., Citation2020), we expected to see read-alouds being used during rest time to a lesser extent. Furthermore, observers noted that in many cases, younger children slept during read-alouds and thus had no opportunity to participate in reading activities. It may be time to replace the deep-rooted Swedish tradition of ‘reading rest’ (Damber, Citation2015) with interactive reading activities that promote children's understanding of reading, as this can be an essential step in promoting children's literacy development.

Finally, the results revealed that few writing activities are offered in the preschools, which is similar to the findings in Alatalo et al. (Citation2022). Emergent writing opportunities were rare for the youngest children, even though early writing in preschools has been shown to have a positive impact on later literacy development (Bingham et al., Citation2017; Gerde et al., Citation2015; Hall et al., Citation2015; Hofslundsengen et al., Citation2016). Just as they miss opportunities to develop reading skills, the youngest children therefore seem to miss out on essential opportunities to develop emergent writing.

We believe that multiple factors may be contributing to the considerable variation observed in preschools regarding access to books and reading and writing activities. One factor may be the large group sizes in the preschools (Jällhage, Citation2020a), which can make it challenging for teachers to carry out reading and writing activities. Another factor may be that there are differences in the number of educated teachers in the preschools (The Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2021), as we might expect that teachers who have completed a teacher education program would have greater insight into the importance of promoting reading and writing activities. The third factor that we believe is important is that preschool teachers have high demands to carry out many activities and teach in several subjects under the preschool curriculum. However, we see the significant differences in children’s opportunities to develop literacy, which is often dependent on which preschool the child attends, as the biggest challenge facing Swedish preschools today. If children are exposed to unequal conditions at a young age, it can also affect their lifelong learning and their conditions later in life.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Helene Dahlström

Helene Dahlström, has more than 20 years of teacher experience from secondary school and teacher education. As a researcher, students’ various conditions for meaning making and text making in multimodal and digital settings have been in focus within the area of literacy. Dahlström has been engaged as a writer on behalf of the Swedish National Board of Education. Recent research also includes issues related to higher education, second language and academic literacy as well as diversity. Dahlström has experience of different research projects, including qualitative methods and mixed methods.

Ulla Damber

Ulla Damber, has more than 20 years of teacher experience in upper secondary school, including development projects and evaluations of practice. As a researcher, teachers and their practices have been in focus, within the areas of literacy, language development and teaching in multicultural school settings, studies published in scientific articles (20<), book chapters, books and debate regarding multilingual matters. Damber has been engaged as a writer on behalf of the Swedish National Board of Education. Recent research also includes issues related to school development projects. Damber has long experience of different research projects, including qualitative methods, mixed methods, narrative analysis and production of screening materials.

Maria Rasmusson

Maria Rasmusson have been teaching at teacher training educations in Sweden since 2001. Her main research interest is in the area of reading and writing development. More specifically, Rasmusson has studied digital reading comprehension among adolescents. She has been responsible for the reading comprehension in the Programme for International Student assessment (PISA) in Sweden during 2008–2016. She has also been involved in the Swedish parts of the large scale assessments, Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) and the Programme for International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). Methodologically, her interests lies manly in quantitative analyses.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [H,D], upon reasonable request.

References

- Alatalo, T., Norling, M., Magnusson, M., Tjäru, S., Næss Hjetland, H., & Hofslundsengen, H. (2022). Read-aloud and writing practices in Nordic preschools. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. Retrieved from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:du-41256

- Alatalo, T., & Westlund, B. (2021). Preschool teachers’ perceptions about read-alouds as a means to support children’s early literacy and language development. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 21(3), 413–435. doi:10.1177/1468798419852136

- Aldén, L., & Hammarstedt, M. (2016). Boende med konsekvens – en ESO-rapport om etnisk bostadssegregation och arbetsmarknad [Housing with consistency – an ESO report on ethnic residential segregation and the labor market]. Retrieved from https://eso.expertgrupp.se/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/.

- Barton, D. (2001). Directions for literacy research: Analysing language and social practices in a textually mediated world. Language and Education, 15, 92–104. Doi:10.1080/09500780108666803

- Barton, D., Hamilton, M., & Ivanic, R. (Eds.). (2001). Situated literacies: Theorising Reading and writing in context (1st ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203984963

- Bingham, G., Quinn, M., & Gerde, H. (2017). Examining early childhood teachers’ writing practices: Associations between pedagogical supports and children’s writing skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 39, 35–46. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.01.002

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

- Damber, U. (2015). Read-alouds in preschool: A matter of discipline?. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 15(2), 256–280.

- Damber, U., & Nilsson, J. (2015). Högläsning med förskolebarn : En disciplinerande eller en frigörande aktivitet?. In M. Tengberg & C. Olin-Scheller (Eds.), Svensk forskning om läsning och läsundervisning (1. uppl., pp. 15–26). Lund: Gleerups Utbildning.

- Dowdall, N., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Murray, L., Gardner, F., Hartford, L., & Cooper, P. J. (2020). Shared picture book Reading interventions for child language development: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Development, 91, e383–e399. doi:10.1111/cdev.13225

- Dynia, J. M., Schachter, R. E., Piasta, S. B., Justice, L. M., O'Connell, A. A., & Pelatti, C. Y. (2018). An empirical investigation of the dimensionality of the physical literacy environment in early childhood classrooms. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 18, 239–263. doi:10.1177/1468798416652448

- Gerde, H. K., Bingham, G. E., & Pendergast, M. (2015). Reliability and validity of the writing resources and interactions in teaching environments (WRITE) for preschool classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 31, 34–46. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.12.008

- Gerde, H. K., Wright, T. S., & Bingham, G. E. (2019). Preschool teachers’ beliefs about and instruction for writing. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 40(4), 326–351. doi:10.1080/10901027.2019.1593899

- Grøver, V., Rydland, V., Gustafsson, J., & Snow, C. E. (2020). Shared book Reading in preschool supports bilingual children’s second-language learning: A cluster-randomized trial. Child Development, 91(6), 2192–2210. doi:10.1111/cdev.13348

- Guo, Y., Justice, L. M., Kaderavek, J. N., & McGinty, A. (2012). The literacy environment of preschool classrooms: contributions to children's emergent literacy growth. Journal of Research in Reading, 35, 308–327. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9817.2010.01467.x

- Hall, A. H., Simpson, A., Guo, Y., & Wang, S. (2015). Examining the effects of preschool writing instruction on emergent literacy skills: A systematic review of the literature. Literacy Research and Instruction, 54, 115–134. doi:10.1080/19388071.2014.991883

- Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Washington, DC: Paul H Brookes Publishing.

- Hermanns, C. (2010). Leveling the playing field: Investigating vocabulary development in Latino preschool-age English language learners (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

- Hofslundsengen, H., Hagtvet, B. E., & Gustafsson, J. (2016). Immediate and delayed effects of invented writing intervention in preschool. Reading and Writing, 29, 1473–1495. doi:10.1007/s11145-016-9646-8

- Hofslundsengen, M. M., Svensson, A.-K., Jusslin, S., Mellgren, E., Hagtvet, B. E., & Heilä-Ylikallio, R. (2020). The literacy environment of preschool classrooms in three Nordic countries: challenges in a multilingual and digital society. Early Child Development and Care, 190(3), 414–427. doi:10.1080/03004430.2018.1477773

- Jällhage, L. (2020a). Barngrupperna är för stora i förskolan (elektronical resourse). Läraren, Lärarförbundet. Retrived from https://www.lararen.se/nyheter/arbetsbelastning/barngrupperna-ar-for-stora-i-forskolan

- Jällhage, L. (2020b). Röster från förskolan om för stora barngrupper (elektronical resourse). Läraren, Lärarförbundet. Retrived from https://www.lararen.se/nyheter/arbetsbelastning/roster-fran-forskolan-om-for-stora-barngrupper

- Liberg, C., Hultin, E., Lundgren, B., & Olin-Scheller, C. (2015). Att lära sig läsa och skriva handlar om mer än bokstäver [Learning to read and write is about more than letters]. Retrieved from https://www.skolaochsamhalle.se/flode/skola/caroline-liberg-m-fl-att-lara-sig-lasa-och-skriva-handlar-om-mer-an-bokstaver/.

- Lonigan, C. J., Faver, J.-A. M., Phillips, B. M., & Clancy-Menchetti, J. (2011). Promoting the development of preschool children’s emergent literacy skills: a randomized evaluation of a literacy-focused curriculum and two professional development models. Reading and Writing, 24, 305–337.

- Lugo-Neris, M., Jackson, C., & Goldstein, H. (2010). Facilitating vocabulary acquisition of young English language learners. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 41, 314–327. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2009/07-0082)

- Morse, J. M. (2003). Principles of mixed methods and multimethod research design. In A. Tashakkori, & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (pp. 189–208). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Nasiopoulou, P., Mellgren, E., Sheridan, S., & Pi, W. (2022). Conditions for children’s language and literacy learning in Swedish preschools: Exploring quality variations with ECERS-3. Early Childhood Education Journal. doi:10.1007/s10643-022-01377-4

- Norling, M. (2015). Förskolan - en arena för social språkmiljö och språkliga processer [The preschool - an arena for social language environment and linguistic processes] (Doctoral dissertation). Mälardalen University. Retrieved from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:mdh:diva-27362

- Persson, S. (2015). En likvärdig förskola för alla barn – innebörder och indikatorer [An equal preschool for all children – meanings and indicators]. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet.

- Salameh, E. K. (2018). Flerspråkig utveckling.[Multilingual development]. In E. K. Salameh, & U. Nettelladt (Eds.), Flerspråkighet – utveckling och svårigheter. Språkutveckling och språkstörning hos barn(2018) (pp. 36–55). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Schmidt, C. (2018). Ethnographic research on children's literacy practices: children's literacy experiences and possibilities for representation. Ethnography and Education. doi: 10.1080/17457823.2018.1512004

- SFS 2010:800. Skollag. [The Swedish Education Act]. Retrieved from https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800

- Sheridan, S., Williams, P., & Garvis, S. (2020). Competence to teach a point of intersection for Swedish preschool quality. Asia-Pacific Journal of Research in Early Childhood Education, 14(2), 77–98.

- SOU 2020:46. En gemensam angelägenhet [A common concern]. Retrieved from https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2020/08/sou-202046/

- SOU 2020:67. (2020). Förskola för alla barn – för bättre språkutveckling i svenska. [Preschool for all – to improve the language development in Swedish]. Retrieved from https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2020/11/sou-202067/

- StataCorp. (2015). Stata statistical software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

- Swedish School Inspectorate. (2018). Förskolans kvalitet och måluppf- yllelse—ett treårigt att granska förskolan [The preschool's quality and goal attainment—a three-year review of the preschool]. Slutrapport. [Final report].

- The Swedish Government. (2022). Förskola för fler barn [Preschool for more children]. Bill: 2021/22:UbU24. Retrieved from https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/arende/betankande/forskola-for-fler-barn_H901UbU24

- The Swedish National Agency for Education. (2018). Curriculum for the preschool. Lpfö 18. Retrieved from https://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=4049

- The Swedish National Agency for Education. (2021). Barn och personal i förskola. Beskrivande statistik [Children and staff in preschool. Descriptive statistics]. https://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=9716

- The Swedish National Agency for Education. (2022). Statistik över barn och personal i förskola 2021 [Statistics for children and staff in preschool 2021]. Retrieved from https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/fler-statistiknyheter/statistik/2022-04-28-statistik-over-barn-och-personal-i-forskola-2021

- UNESCO. (2017). Global education monitoring report. Paris.