ABSTRACT

This article illustrates the precarious position of Canadian independent musicians in the streaming era. In the first section, we articulate the sound of the Canadian music industry from above, providing a macro-level political economy, looking at multinational conglomerates, streaming technology, financialization, consolidation, and inequality. In sections two and three, we listen to the sound from below using ethnographic methods, relaying the experiences of independent musicians within an increasingly precarious industry. Based on feedback from the musicians we interviewed, we conclude by providing a series of recommendations and ideas to foster a more equitable, community-based music culture.

Introduction

“I thought it was this viable career choice. That with enough effort, you could make it work,” laments Lee Klippenstein of Slates and Screaming Targets when reflecting on a decade-plus career as a musician. “I certainly don’t think that’s the case now.” Many independent musicians, in Canada and elsewhere, find themselves in a similar position, increasingly unable to support themselves making and performing music. Unless something “emerges to challenge the status quo” that has made a working career as a musician so unsustainable, John K Samson of the Weakerthans and Propagandhi expects only “further consolidation and a narrowing of who can live as a musician.”

This article illustrates the precarious position of independent musicians in the streaming era.Footnote1 Though its focus is Canada, it joins a number of articles (CitationMühlbach and Arora; CitationNickell; CitationTowse) that position a nation’s music industries and its independent musicians within the globalized streaming music era. What this article adds to the conversation is a dual methodological approach, using a combination of critical political economy and ethnography. In the first section, we articulate the sound of the Canadian music industries from above, providing a macro-level political economy, with attention paid to multinational conglomerates, streaming technology, financialization, platforms, consolidation, and inequality. We are influenced by CitationHesmondhalgh’s call for “more systematic historical comparisons … beyond an excessive focus on new players … to the cultural-industry and political-economic contexts in which those organisations are embedded” (“Is Music” 19). With a broad, statistical overview, we aim to map systemic inequalities and demonstrate the existential hardships faced by independent musicians in Canada.

In sections two and three, we listen to the sound from below using ethnographic methods, relaying the experiences of independent musicians within an increasingly precarious industry. Our study uses interviews with seventeen artists from Edmonton, Alberta, and Winnipeg, Manitoba. We are influenced by Cohen’s call for “an ethnographic approach to the study of popular music, used alongside other methods [that] would emphasise that popular music is something created, used and interpreted by different individuals and groups … a human activity involving social relationships, identities and collective practices” (127). Cohen warns against “a reliance upon theoretical models abstracted from empirical data, and upon statistical, textual and journalistic sources,” which need “to be balanced by a more ethnographic approach” (123). By incorporating theory, data, and journalistic sources, along with interviews of independent Canadian musicians, we aim to provide an account of the dire situation of our musical culture that is being accelerated by corporate consolidation, financialization, and platformization. Based on feedback from the musicians we interviewed, we conclude by providing a series of recommendations and ideas to foster a more equitable, community-based music culture.

The Political Economy of Canadian Music

When it comes to studying national music industries on the periphery of the American-led global music industries, an attention to global macroeconomic concerns is key. Many of the world’s national and regional music industries are increasingly affected by a tight oligopoly of transnational (mostly American) music, technology, and financial companies. Media consolidation is not a new concern, but its intensification through financialization, streaming technology, and platformization is tightening the grip of power held by the biggest companies. The political economy of music is heavily shaped by only two or three massive conglomerates in each subsector, shaping the opportunities for musicians of all stripes. In recording and publishing, the “Big Three” of Universal Music Group, Sony Music Group, and Warner Music Group dominate the industry. Reports range from the Big Three controlling at least 70% of the global recording and publishing market in 2019 (CitationStasen), to as high as 86% of the North American market in 2016 (CitationChristman). The exploitation at the heart of record label contracts is well documented (CitationStahl, Unfree; CitationArditi). In the live concert and ticketing business – often a musician’s leading revenue source – LiveNation (which owns Ticketmaster) and Anschutz Entertainment Group (AEG) form a duopoly, controlling the rights to perform at the largest venues and festivals, while dictating onerous terms to musicians. American terrestrial radio stations have been consolidated into homogenous, centralized networks by iHeartMedia, Entercom, and Cumulus, reinforcing the power of American superstars in global markets. The satellite radio market, once a promise of expanded diversity and opportunity, is now dominated by the merged entity SiriusXM. Internet radio was another format with potential for range and innovation; its biggest success, Pandora, was recently acquired by Liberty Media, a conglomerate that also owns SiriusXM, has investment stakes in LiveNation and iHeartMedia, and whose Chairman, John Malone, openly stated that “the goal would be to get to full consolidation” (qtd. in CitationSzalai and Vlessing). Into these highly consolidated music industries, streaming music arrived on a promise of expanded access and opportunity; the reality has been quite different.

Streaming in the Music Industries

The shift to digital music has reconfigured the music industries in myriad ways. Scholars often chart these changes by conceptualizing a new relationship to music: moving from consumer electronics to “networked mobile personalization” (CitationHesmondhalgh and Meier), based on the “digital music commodity” (CitationMorris), mediated through overlapping networks and “technological assemblages” (CitationLeyshon), which craft a “branded musical experience” (CitationMorris and Powers) for “users” that are provided a service rather than consumers who are sold a product (CitationAnderson). An adjacent historical paradigm is provided by Towse, who outlines the way digital service providers (DSPs), or platforms (such as Spotify, Apple, and Amazon), have altered the established method by which songwriters and recording artists are paid. Rather than discrete sales, a DSP uses platform pricing for subscriptions and ad-based services, which has depressed the royalty rates paid to musicians, now “too low to fully sustain a full-time career as a recording artist for the majority” (CitationTowse 14).

As the largest growth market in the music industries in recent years, streaming platforms have been subject to a growing body of scholarship. Marshall provides an early analysis of the ongoing controversy over artist royalties, focusing on Spotify’s meager payouts to musicians and its “pro-rata” revenue sharing model, in which pay to musicians is allocated according to total number of streams across the platform, rather than a user’s subscription payment being divvied up among the musicians they listened to individually. Spotify’s payment model favors big labels with many clients and extensive catalogs, while disadvantaging independent musicians and labels without the comparative scale. CitationHesmondhalgh further discusses the potential advantages of a user-centric model, rather than pro-rata, while also challenging simplistic criticisms of streaming music services, such as the reliance on dubious “per-stream” rates and the lack of systemic analysis (“Is Music”). Vonderau adds to this holistic understanding of streaming, arguing that Spotify is not just a music service, but operates at the intersection of advertising, technology, music, and finance. The importance of debt financing and brokerage to Spotify’s rise, as Vonderau delineates, is essential to understanding the political economy of music; lurking in the shadows behind this technological transition to streaming music is the power of speculation.

Financializing and Platformizing the Music Industries

Financialization – the accelerated growth and power of the financial sector and its extractive logic – has had a dramatic but oft-unacknowledged impact on the consolidation of the global music industries in the last two decades. Private equity firms are a case in point; these investment funds buy companies using debt that is raised against the assets of the target company itself, referred to as “leverage.” The investment fund then pays itself to restructure and financially engineer the company to “maximize efficiency,” then seeks to sell the streamlined property at a profit. Warner Music Group, for example, was acquired by Bain Capital, Thomas H. Lee Partners, and Providence Equity Partners in 2004, which resulted in mass layoffs, including staff and musicians, as well as the reduced operational capacity of many of the historic labels within Warner Music Group. In 2007, Terra Firma used debt-financing to acquire venerable British music company EMI and proceeded to lay off the existing management and nearly half of its workforce. Unable to restore revenues, Terra Firma forfeited control of EMI to its creditors; EMI’s publishing arm ended up in Sony Music Group, while its recording arm was sold to Universal Music Group. The result of this instance of predatory financial extraction was a reduction from the “Big Four” record labels to the “Big Three.”

Radio has been another target for financialization. In 2008, Bain and THL acquired Clear Channel, the largest US operator of radio stations. The layoffs were immediate, with many rounds of layoffs in the subsequent years. Smaller stations were sold off, the focus was shifted to only the most profitable stations, and local programming was replaced with syndicated programming. Saddled with $20 billion of debt by its private equity owners, the renamed iHeartMedia filed for bankruptcy in 2018 in order to restructure its debt. The second largest radio operator in the country, Cumulus, experienced a similar decade of private equity, consolidation, debt, streamlining, and homogenization. The private equity experiences of Warner Music Group, EMI, iHeartMedia, and Cumulus–four of the largest conglomerates in the music industries–demonstrate that the story of private equity is not just the rapid looting of profit in its successes, but also the debt-saddled wreckages it leaves in its failures.

In addition to private equity, other financial firms are circling the music industries. Institutional investors, such as Blackrock and Vanguard, have assembled dominant investment stakes in all major media companies, using this “common ownership” to reduce operational capacity, limit competition, and raise prices (CitationdeWaard). Investment groups, such as Hipgnosis Songs Fund, Round Hill Music, Concord, Shamrock, Primary Wave, and Lyric Capital Group, are acquiring recording and publishing rights in an effort to turn catalogs of songs into speculative assets. Hipgnosis, for example, owns an investment stake in more than 57,000 songs (over a thousand of which are #1 songs), is valued at over 2 billion dollars, and recently received a billion dollar investment from private equity company Blackstone to continue its mission of “establish[ing] songs as an uncorrelated asset class with attractive risk adjustment returns” (CitationIngham). Canadian musicians such as the Weeknd, Justin Bieber, Carly Rae Jepsen, and Neil Young have had their publishing rights financialized in this manner. In conjunction with this external financial pressure, the Big Three labels have enacted internal strategies of financialization, such as monopolistically leveraging their back-catalogs in order to gain equity stakes in streaming music companies, such as Spotify, Rdio, and Soundcloud. Finding great success in this investment-based strategy that requires no sharing of royalties with its artists, the Big Three labels now operate their own venture capital funds, as do all major media companies.

As the financial sector consolidates and extracts capital from established media sectors and copyright licenses, Big Tech companies create the platforms that are reshaping the working practices of today’s creative workers. This “platformization of cultural production” has sharpened “expectations of digital visibility in cultural work” and led to a distribution of revenue that is “notoriously uneven and subject to very strong ‘winner-take-all’ effects,” with massive uncertainty surrounding the ability for small-and-medium businesses or artists to “generate sustained long-term revenue” (CitationNieborg 25, 30–31). There is a long history of exploitation and precariousness in the cultural and creative industries, of course, one that predates the financialized and platformized streaming media era (CitationHesmondhalgh, “User-generated”; CitationHesmondhalgh and Baker). Workers in all creative sectors have been faced with an increasing reliance on entrepreneurialism and tasks adjacent to the making of art, music, and cultural products, while cultural policy has been limited in its capacity to respond to unsustainable working conditions (CitationMcRobbie). The music industries have numerous examples of uneven power dynamics between the record industry and recording artists (CitationStahl, “Primitive”). And though more musicians can release music today, evading previous gatekeepers to digitally distribute their own work to streaming services for a fee, not requiring a record label, their ability to actually make a living wage doing so are severely curtailed. There is a distinct lack of transparency when it comes to how musicians are being remunerated, making historical comparisons difficult (CitationHesmondhalgh, “Is Music”), but it is becoming clear that the result of this financialization, consolidation, and platformization in the music industries has been escalating inequality: a boon for corporations and superstar musicians, but devastating for average musicians.

A recent Citigroup report found that the U.S. music industry generated $43 billion USD in 2017, but artists received only 12% (CitationSanchez). Within that meager 12%, there is stunning inequality among artists and it’s worsening: the top 1% of artists accounted for 77% of all recorded music income in 2014 (CitationMulligan). By 2020, the top 1% accounted for 90% of streams and the top 10% of artists accounted for 99.4% (CitationSmith). Another analysis showed the 10 top-selling tracks command 82% more of the market and are played almost twice as much on Top 40 radio than they were a decade ago (CitationThompson). The top 1% of live performers earned 26% of worldwide concert revenue in 1980, but that market share had climbed to 60% in 2017, taking in more revenue than the bottom 99% combined (CitationKrueger 85). The top 5% of artists also increased their share of the pie, from 62% to 85%, meaning the market share for the remaining 95%–the vast, vast majority of working musicians–has decreased from 38% of the market in 1982 to just 15% in 2017 (85). Meanwhile, the average American musician made only $21,300 from their craft in 2018 and 61% report music income is not sufficient to meet their living expenses (CitationKrueger and Zhen). In Canada, the average musician only makes $17,900/year, less than half of the average Canadian worker’s income, and well below the poverty line (CitationHill, “A Statistical”). It is more winner-take-all in the music industries than ever before and the vast majority of creators are struggling to earn a living.

The Canadian Music Industries in the Streaming Age

The Canadian record industry has ties to the much larger American record industry through a domestic-international or subsidiary-parent company relationship. Canadian subsidiaries have typically developed national artists for a domestic market to determine the potential for international distribution. Beginning in the late 1960s, the existence of Canadian subsidiaries of major multinational labels “mirrors an international pattern; these firms have set up national branches and manufacturing plants in many countries” (CitationStraw 102). As one example, the wider political economy surrounding Capitol Records’ first Canadian record pressing plant, which opened in 1976, indicates an industrial logic that was largely American in structure (CitationFauteux et al.). Many Canadian independent record labels that have released albums by Canadian artists have developed distribution deals with major labels. For instance, the Toronto-based Arts & Crafts Records, home to notable indie acts like Broken Social Scene and Feist, had EMI Music Canada as its distributor until 2013 when EMI was merged into Universal Music Canada. Furthermore, the label’s co-founder Jeffrey Remedios is now the CEO of Universal Music Canada. While there is an increasing focus on digital music and streaming services today, lessening the importance of producing, distributing, and retailing material cultural products like records, Canada is still part of a global context in which large, often American, record or tech companies retain significant influence.

Transnational financialization and consolidation means the livelihoods of Canadian musicians are subject to the structural constraints established by Fortune 500 CEOs, Silicon Valley programmers, and hedge fund managers. The consolidation of the Canadian media sector only exacerbates the situation. The Canadian Media Concentration Research Project notes that vertical integration within the country “is very high by historical standards and almost four times current levels in the United States,” as the top five media companies (Bell, Rogers, Telus, Shaw, and Quebecor) accounted for 71.1% of the $80 billion CAD network media economy in 2016 (CitationWinseck). Vertical integration has real impacts; the control of the Canadian radio sector by the ten biggest radio groups grew from 50% in 1997 to 82% by 2018, leading to homogenized playlists and limited exposure for new musicians (Canada, Minutes). The 2006 policy for commercial radio noted that the sector was financially sound, in part due to the fact that the 1998 policy increased the limits on the number of stations a licensee could own in a single market (CitationCRTC). Alongside this increased consolidation is the fact that commercial radio and other major music industries in Canada have been “slow to embrace genres outside of Rock and Country” (CitationSutherland 230). For this reason, many independent artists and musicians who perform music not typically heard on more mainstream channels have sought out Canada’s public and campus radio sectors for airplay.

Radio in Canada has historical and ideological connections to ideas about national identity and community (however ambiguous) and these ideas shape the mandate of a national public institution like the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). Section 3(1)(b) of Canada’s Broadcasting Act (1991) claims that the broadcasting system provides a “public service essential to the maintenance and enhancement of national identity and cultural sovereignty.” The CBC has a mandate to reflect the regional and cultural diversity of Canada; to contribute to shared national consciousness; and, to develop Canadian talent (Canada, “Organization”). Thus, the CBC makes efforts to showcase music from across Canada’s regions and it is mandated to program at least fifty percent Canadian content. In addition to the CBC, all Canadian music radio must program a certain percentage of Canadian musical selections across the broadcast week in the form of Canadian content regulations. Commercial stations are to have at least 35 percent Canadian music selections across the broadcast week. Campus stations are also usually licensed at or above 35 percent. Most significantly, campus stations are licensed to reflect their local communities and to complement commercial and public radio programming. This means that music programming often prioritizes local artists and music from a wide variety of styles and genres (CitationFauteux; CitationMacLennan; CitationMastrocola). Established in 1971, the aim of these content regulations was to boost the Canadian music industries (see CitationMuia), but they have not been updated or applied to internet consumption, like streaming music services, and are therefore less relevant to the financialized, consolidated, and platformized global music industries.

Responding to this worsening media climate, the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage studied remuneration models for Canadian artists and creative industries in 2019. The resulting report (Canada, “Shifting”) focused on the industry term “value gap,” “a disparity between the value of creative content enjoyed by consumers and the revenues that are received by artists and creative industries” (6), which it linked to “a severe decline in the ability of artists to earn a middle-class income” (7), in large part due to “wealth [having been] diverted from creators into the pockets of massive digital entities” (23). A report generated by Music Canada agreed, arguing that the creative labor of Canadian musicians “subsidize[s] major online platforms and telecommunications conglomerates through Canadian copyright exceptions that prevent performers and record labels from being properly compensated” (“Closing” 10). The total cost it estimates to have been lost to the Canadian music industry since 1997 is over $19 billion (“Closing” 18).

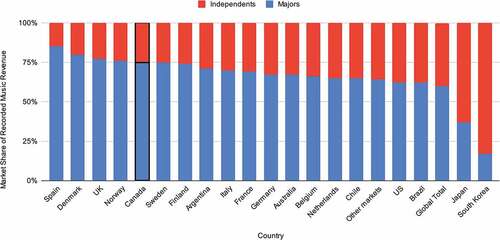

While pointing to the extractive and consolidated nature of tech platforms and telecoms is certainly justified, Music Canada fails to mention the effects of the concentration of the Canadian recording industry, perhaps because it is a trade group funded by the Canadian subsidiaries of the Big 3 record labels: Sony Music Entertainment Canada, Universal Music Canada, and Warner Music Canada. According to the WINTEL Worldwide Independent Market Report in 2018, Canada has one of the highest rates of major label market share in the world, at 75%, as indicated in . Only Spain, Denmark, and the UK had a higher rate. Correspondingly, Canada has one of the lowest rates of independent record label market share at 25%. Even the United States has higher (38%). The global average is 40%, while more equitable countries like Japan (63%) and South Korea (83%) should be the goal. It is no wonder that Music Canada’s solution to the “value gap” is punitive copyright legislation; the Big 3 record labels would continue to profit handsomely within their oligopoly.

Figure 1. Market Share of Major and Independent Record Labels Globally, 2018. Data: WINTEL Worldwide Independent Market Report 2018. Full data available at CULTCAP.ORG/DATA.

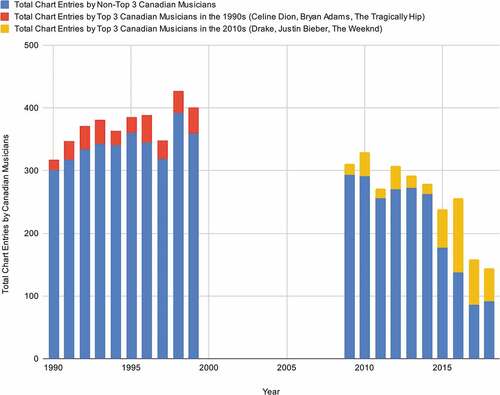

Within this consolidated Canadian industry, there are many inequalities. Three of the biggest global streaming superstars are Canadian – Drake, the Weeknd, and Justin Bieber – and they have dominated in the streaming era: from 2005 to 2017, they had the top 8 most streamed songs of Canadian musicians, 31 of the top 50, and 72 of the top 150 (CitationBliss). Each of the three has continued to rack up global hits and chart records since that time and their success has positive effects for the Canadian music industries, facilitating jobs and international attention. However, their success also casts a long shadow; most recent statistics on Canadian music are artificially inflated by these three megastars, clouding our picture of the health of the industry. Sales and streaming figures that subtracted these three artists would present an even more alarming reality for the average musician. What might appear as a profitable, vibrant industry from baseline numbers is in fact dominated by three musicians, all three of whom are signed to US-based Universal Music Group. depicts a representative sample of chart entries of Canadian musicians on the Top 100 Singles Charts in Canada during two time periods: 1990–1999 and 2009–2018. The 1990s, the height of both the CD boom and Canadian content regulations, witnessed a wider variety of Canadian musicians making popular music that reached a substantive Canadian audience, at least as measured by charts. There were 306 distinct Canadian musicians who made the top 100, 3,730 total chart entries, 1,154 unique songs, and the top 3 musicians controlled only 5–10% market share of the chart. The streaming era, by contrast, has been notably less diverse for Canadian music: only 246 distinct Canadian musicians (including many cover songs and one-hit wonders from song competition television series), 2,588 total chart entries, 764 unique songs, and a dramatic trend line down in all categories, except the increasing market share of Drake, Justin Beiber, and the Weeknd, which reached as high as 46% in 2016 and 2017.

Figure 2. Canadian songs on top 100 singles charts in Canada: 1990–1999 & 2009–2018.Data: RPM Magazine (1990-1999); no data (2000-2008); Billboard Canadian Hot 100 (2009-2018). Full data available at CULTCAP.ORG/DATA.

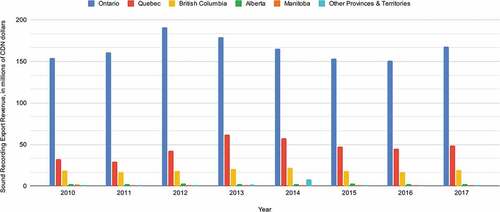

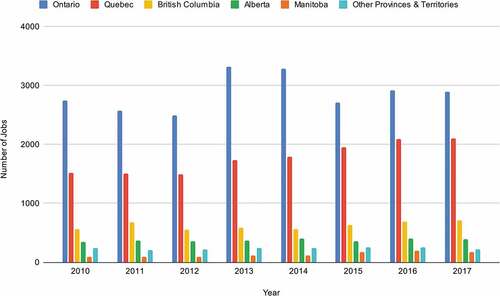

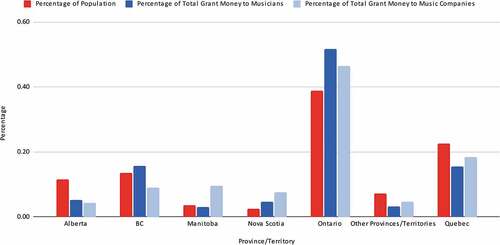

Regional inequalities are widening as well. Ontario, particularly the cultural hub of Toronto, has a disproportionate significance within the Canadian music industries, with nearly half of music sector jobs nationwide, over 60% of Canadian music publishing and recording export revenue, and 58% of the Canadian total GDP generated by this music sector as of 2017 (“Industry Profile – Music”). demonstrate this inordinate power of Ontario within the Canadian recorded music industry, with a limited sector in Quebec, and the remaining provinces and territories struggling to maintain jobs and exports of recordings. Government grants help mitigate this imbalance, as discussed by musicians below. But in the case of grants awarded by the Foundation Assisting Canadian Talent on Recordings (FACTOR) from 2013 to 2020, as seen in , more than half of total money went to Ontario musicians, despite the province having less than 40% of the population. Correspondingly, other provinces and territories receive a disproportionately lower amount of funding compared to their population. To make matters worse, conservative governments at both the federal and provincial level continue to slash funding to arts and culture programs when possible: in Ontario, funding for the Ontario Music Fund was reduced from $15 million to $7 million by the province’s Progressive Conservative 2019 budget (“Ontario government”); in Alberta, the United Conservative Party enacted a 5 per cent budget reduction to the Alberta Foundation for the Arts (“Arts and Creative”); and in Manitoba, the Progressive Conservative Party proposed $8 million in cut to community groups, including the Winnipeg Arts Council (CitationKavanagh).

Figure 3. International Exports of Canadian Sound Recording Industry, 2010-2017.Data: Statistics Canada. Table 12-10-0116-01 International and inter-provincial trade of culture and sport products, by domain and sub-domain, provinces and territories (x 1,000,000). Full data available at CULTCAP.ORG/DATA.

Figure 4. Jobs in Canadian Sound Recording Industry, 2010-2017.Data: Statistics Canada. Table 36-10-0452-01 Culture and sport indicators by domain and sub-domain, by province and territory, product perspective (x 1,000). Full data available at CULTCAP.ORG/DATA.

Figure 5. FACTOR Grants Awarded to Musicians and Music Companies Based on Province/Territory Compared to Population, 2013-2020.Data: FACTOR (2020); Statistics Canada. Table 17-10-0009-01 (2020). Full data available at CULTCAP.ORG/DATA.

Issues of diversity and inclusion are another concern when considering worsening inequality within the streaming age of music. Amidst this corporate consolidation, listener data are showing a reduction in the diversity of music across vectors of gender, class, and ethnicity. A report on Spotify’s most-streamed artists in 2018 indicates that all of the top artists are men (CitationByager). A deeper analysis of 600 Billboard Hot 100 songs from 2012 to 2017 found an average of 16.8% female performers, 12.3% female songwriters, and only 2.1% female producers (CitationSmith et al.). A UK study found only 12% of musicians in 2019 were from a working-class background, down from 20% in previous years; women and people of color were further disadvantaged (CitationCarey et al.). In Canada, female artists make 82 cents of total income for every dollar of male artists, with Indigenous artists making only 68 cents on the dollar (CitationHill, “Demographic”). With this overview of the political economy of Canadian music, it is clear that independent musicians face undue hardship in pursuing their career. The next step is turning to the musicians themselves, listening to their perspectives and values, in order to advocate on their behalf.

Amplifying Artist Perspectives in the Streaming Music Era

To get a sense of how artists in Canada have been navigating their careers within the context of the political economy of music in Canada, we interviewed nine musicians in Edmonton, Alberta, and eight in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Some of these artists continue to live and work in Edmonton and Winnipeg while others have moved to larger cities in order to develop their careers. Interviews ranged from thirty to ninety minutes and took place in person between December 2019 and March 2020, although some were conducted via phone or video chat for artists who were located elsewhere. The interviews followed a fixed set of questions, but with exploratory contextual prompts to continue in areas that seemed of particular interest to the project and the interviewee themselves. Possible themes were identified prior to interviews, then iteratively updated as we listened to and reflected on the stories and answers shared by the musicians. The career paths of these artists are unique but what unites them is some distance from the major record industry. These are artists without major label representation and without regular commercial radio airplay. Some expressed an aspiration to eventually find commercial success while others have maintained a do-it-yourself and independent ethos throughout their careers.

These cities were chosen for practical reasons (one member of our research team lives in Edmonton and one in Winnipeg) but also to call attention to cities that are infrequently the focus of writing on music in Canada. Studies of music making in Canada predominantly focus on larger cities with more venues, music-related businesses, and radio stations, such as Toronto, Ontario or Montreal, Quebec. While both Edmonton and Winnipeg are mid-sized cities (the population of the former is 981,280 as of 2017 and the latter is 749,534) with a number of music venues and recording studios, they do not maintain the music infrastructure and support of Canada’s larger urban centers. Both cities are also isolated in terms of their proximity to other large cities, although Edmonton is relatively close (about a three-hour drive) to Calgary, Alberta’s other major municipality. In Winnipeg in particular, this has led to a certain pride in the local scene, as it is difficult to travel elsewhere for shows. These interviews highlighted three aspects of the artist experience that are relevant to analyzing the political economy of music in Canada: the core and peripheries of “the industry,” touring and geography, and grants and funding.

The Core and Peripheries of “The Industry”

Because our interview subjects either live or have lived in the mid-sized cities of Winnipeg and Edmonton, there is often a career trajectory that involves moving to a larger city where more music infrastructure is located. Some interviewees mentioned the ability to find more work opportunities in bigger cities and that there is a better chance of having a gatekeeper, like a SiriusXM programmer, present at a live performance in Toronto. Both Colleen Brown and Cayley Thomas are singers, songwriters, and instrumentalists who moved to Toronto from Edmonton. Brown commented on the increased prominence of the business side of music in Toronto and explained that “it just felt like almost every time I watched an artist build up in Edmonton, there would be some kind of wall where it just wouldn’t build past a certain point.” Natanielle Felicitas, a freelance cellist, expressed a similar sentiment in the Winnipeg context but with some frustration about this trajectory: “I know everyone sort of concentrates themselves in Toronto and a lot of Winnipeggers are told to go there if they want to have the next level up. It would be nice to see Winnipeg have … more industry, more middlemen.” For other artists, however, a city like Winnipeg represents more opportunities for producing and performing music. The late Kelly Fraser, a beloved Inuk pop singer and Juno Award nominee, detailed a music journey through bringing back the “Inuit drum” which was “lost years ago from missionaries telling us to ban it.” Fraser added, “I learned how to play in Inuit Studies in Ottawa’s Nunavut Sivuniksavut for two years. I was able to bring it back to my community … [and] collectively we brought that drum back.” She later found that it was hard on her mental health to be back in her community in Nunavut “because I didn’t have a lot of support and I wasn’t saving money. … So I moved away to Winnipeg to try to make it, though it’s very hard.” Canadian musicians often wrestle with the dilemma to stay in their community or relocate to a larger city with more industry opportunities.

The process of becoming acquainted with different levels or tiers of the music business can be tricky. For many musicians, there is a need to be strategic with respect to deciding when to establish partnerships with labels or other industry intermediaries like a publicist or a booking agent, and how much of their own money to spend. Most interview subjects commented on the fact that they have worked with a manager or a publicist but that these partnerships were temporary and timed to align with a major funding opportunity (such as a grant application) or an album release. This process of negotiating budgets and partnerships to align with key benchmarks of one’s career seems to be a strategy that defines the experience of independent musicians in Canada. One indie solo artist from Edmonton mentioned that her publicist was the most expensive line on her marketing budget but that little return had come from this expense. Marti Sarbit, vocalist and songwriter of Imaginary Cities and Lanakai, explained that a manager was essential for putting together large grant applications. This perceived requirement to participate in “the industry” in a specific way can be a significant obstacle for many. Fraser indicated that forms of institutional racism can be a barrier for participating with labels, an issue she connected to a longer history of colonialism in Canada: “I don’t know if labels that are mostly run by white people or people who live in the West with Western ideologies and values, I don’t think they’d be able to see what I’m trying to do, trying to teach.” She did try to work with a label for her album Sedna but the label requested that she sing only in her language; she wanted to sing half in English and half in Inuktitut because that is how she teaches. She decided not to work with the label given their efforts to control her practice.

Touring and Canadian Geography

A study on the music ecosystem in Alberta noted that 73% of artist income comes from performances and touring (“West Anthem”). Studies out of the US corroborate this finding; the Future of Music found that much artist revenue has to be sustained by aggressive touring (“Artist Revenue Streams”) and The Creative Independent indicated that most musicians in the US are not able to earn a living wage through music-related work, with most income coming from performing/touring at 61% (CitationKöerner and Kladzyk). Touring is not an option that is accessible to everyone. The increasing emphasis on live music within a musician’s workload raises issues for those in Canada, given a vast geographic area and low population. Musicians living and working in the northern territories have an especially difficult time touring, facing exceptionally long distances and expensive travel options. Although streaming services help reach audiences beyond borders, it forces musicians to rely on live shows and touring to generate an income, as opposed to selling albums (CitationWeaver). Some artists noted the increasing importance of festivals and showcases, in which one can spend a few days in one area and perform and network with the hopes of building a team to help advance their career. Some felt that it is difficult if not pointless to tour across Canada, finding it to be more effective to fly to a different region and visit a number of towns or cities in that particular area.

In most cases, artists emphasized the necessity of touring, although the financial return of this endeavor varied across responses. Klippenstein said that for his Edmonton-based bands, it is usually “a 50/50 split between show sales and records and merch sales … almost always strictly vinyl for us.” He added that live shows and merch sales have “been, really, the only thing to sustain us.” Fraser noted that an increase in popularity had meant having to tour and more regularly. Before, she avoided planning tours but instead, “specifically allowed [herself] to be available to Indigenous people who want me to play at their events on their reserves in Nunavut” and did “a lot of workshops and motivational speaking.” Winnipeg-based Samson said that most of his income comes from live revenue but when he plays with a full band he makes “what the band makes and it’s not very much.”

The logistics of organizing tours and live performances is often a fundamental aspect of a Canadian musician’s career and thus a number of musicians discussed working with booking agents. This has had both positive and negative outcomes. Klippenstein said that an agent has resulted in slightly higher guarantees than if he had booked shows himself but that the end result is often ending up on bills with mismatched bands and “poorly attended shows.” One’s relationship and experience with venues is another aspect of the booking process that many noted as significant, particularly when planning and organizing shows themselves. Transparency and communication from the venue is crucial. As Big Dave McLean, a celebrated Winnipeg blues guitarist, songwriter, and Member of the Order of Canada, said, “If I’m going to Sault Ste. Marie, well it’s going to take me a while to get there and I sure hope there’s a gig for me when I get there. … In the past I have shown up to, ‘Oh gee, I’m sorry I forgot that I booked this guy too.’” Sarbit added that some venues “will send you this beautiful contract ahead of time and give you all the information you need. Love those venues.”

One of the most striking takeaways from the artist perspective on touring in Canada is that geographic and financial obstacles can determine the logistics, and thus often the sound, of the performance. Thomas indicated that her recordings are quite layered, and she has thought, “Oh, why did I have to include a vibraphone!? … How to pair that down because that’s a big thing. I guess, to create a product that you can recreate with as little resources as necessary.” Similarly, Felicitas said that “It’s cheaper for just one person to fly there and tour Eastern Canada with the Eastern string players as opposed to bringing me along.” Further, genre plays a role in determining one’s ability to tour and perform in smaller cities or towns. Josh Sahunta, an Edmonton-based R&B and pop singer-songwriter, explained that because he fits within the “genre of easy listening” he can get a wide variety of bookings because his music “is not really something that would be off-putting in any setting.” Based on the fact that some artists expressed that it can be difficult to reproduce the sound of the record in a live context given the additional costs it necessitates, it can be said that the sound of the music one hears in a live music context is shaped by financial and logistic realities and these obstacles are more prominent for new and independent artists. Certain genres and styles of music that lend themselves to solo artists or smaller outfits seem to travel more efficiently.

Government Grants and Funding

One opportunity for artists in Canada is a robust funding framework for musical activities including recording, promotion, and touring. Shapiro explains that Canada “has one of the most extensive systems of any country for funding of the arts and is viewed as a model case by other nations” (90). The Liberal government’s Budget 2021 included $70 million over three years to Canadian Heritage for the Canada Music Fund (CMF), including $50 million in 2021–22 to help the live music sector with difficulties faced during the COVID-19 pandemic. The CMF funds major Canadian granting organizations FACTOR (for the English market) and Musicaction (for the French market). Sahunta has taken advantage of this system and describes grants as “invaluable” and has used them for tours, showcases, and recording. By no means is this a perfect funding framework, but a number of musicians emphasized the reliability of grants as a significant source of financial backing. One Juno Award winning folk singer-songwriter from Alberta said that “the most funding that I get is from grants. I would say that about 50% of them are Indigenous-based grants. And that’s the money that goes towards my travel and towards creating new albums.”

Grants range from those provided by local organizations such as municipalities, radio stations, and banks, to organizations at the provincial and federal levels. Typically, the more local the grant, the easier it is to acquire, at least in mid-sized cities like Edmonton and Winnipeg. Klippenstein said that three of the most expensive albums recorded over his career “were funded by a radio station that had no radio shows that played any sort of music similar to [his bands].” This was called the “10k20 program,” which involved twenty bands receiving $10,000 and was a “fairly straight forward grant to write.” The larger grants offered by FACTOR are said to be more difficult to acquire and they often require assistance (such as a manager) as well as money to be put forth by the artist themselves. FACTOR was founded in 1982 by three of Canada’s largest broadcast chains in partnership with the Canadian Independent Record Production Association and the Canadian Music Publishers Association. Over the years, it has expanded its funding opportunities but has worked to manage a balance between “providing opportunities to those artists and companies in need of support, but also to those with potential to reach some level of commercial success” (CitationSutherland 223, 226). About half of our interview subjects had applied to FACTOR for funding while others preferred smaller, low-stakes, regional or local grants. FACTOR’s smaller grants, like the Emerging Artists Program, introduced in 2007–08, still require a certain level of industry experience, such as demonstrating a certain threshold of sales and radio airplay (CitationSutherland 227). Across our interviews, the importance of grants was routinely emphasized, and artists have used a variety of funding sources to help sustain their careers and livelihoods.

Some grants do come with significant barriers, particularly the larger ones that support a range of activities across an extended period of time. Thomas described the FACTOR Juried Sound Recording (JSR) grant as “the Cadillac … of the FACTOR programs.” She said, “while a very generous grant, it requires you to put a bit of your own money in.” Klippenstein expressed some frustration with the need to account for statistics and keep accurate records for the purpose of putting larger grant applications together. With a delightfully Canadian example, he noted that it can be hard to keep track of record sales on the road: “I don’t know how many records we sold, because the book fell in a snowbank or whatever.” Fraser described the grant writing process against dire circumstances under which her bandmates were low on money and starving. Some of her bandmates “went days without eating.” A grant was approved by the territory (Nunavut) and she said, “one of the things that they told me was, ‘next time you write your proposal, make sure you’re grammatically correct.’ And, it’s like, right now, that’s not my biggest priority.”

In a larger arts-funding context, there has been a noted turn to instrumentalized benchmarks for acquiring and justifying grants. Another example of a major industry grant in Canada is the Radio Starmaker Fund, one developed by private broadcasting trade association the Canadian Association of Broadcasters. As Shapiro notes, this fund reflects a move to support “stars” as opposed to Canadian culture or content and the fact that “new talent would have to sell between 2500 and 10,000 units in Canada to qualify” meant that a significant number of artists were ineligible (94). Beyond Canada, Behr has described how a focus on a “free-market economy” has shaped state funding of the arts in a number of national contexts, where money spent on “the arts came to be spoken of in relation to the returns it generated: profits, tax revenues and jobs” (279). A common sentiment expressed by interviewees was that grants tend to privilege “the people who are more strategic and less artistically driven” (as said by one anonymous interviewee). Others bemoaned the fact that Facebook “likes” and YouTube “views” become part of the criteria for a successful application. Greg MacPherson, Winnipeg singer-songwriter and co-owner of indie record label Disintegration Records, raised questions about what sort of music might get funded if we circumvented ideas about instrumental return. He said, “I would love to see all that support going into … some weird electronic music from The Pas [a small town just over 600 km northwest of Winnipeg] or something that’s very different and unique.”

There is a relationship, then, between a sort of homogenization of music finding success through grants and within the higher echelon of the music and record business in Canada. Samson said, “I do feel like the homogenization of the industry is basically leading to artists, musicians, being mostly people like me … middle-class people with support, people who’ve kind of won various lotteries.” These points echo Sutherland’s claim that FACTOR has had “well-developed procedures for responding to ongoing changes in its target sector” but this has not been matched in its effort to address matters of diversity through the 2000s (despite this being an emerging government priority not specific to the music industry) (229). Many other participants questioned whether a polished grant proposal is strongly correlated with interesting music.

Community-led Values and Opportunities

Throughout our interviews with musicians there was a pronounced focus on the value of community between artists and local institutions. Music scenes offer a means by which to consider music’s relationship to the local, a relationship that informs “notions of collective identity and community” (CitationBennett 3) and they are shaped by institutional spaces that bring people together through listening to music and participating in the production and circulation of music (CitationFauteux 130). Scenes can be shaped by genre conventions and expectations as well. In O’Connor’s writing on punk, “scene” means “the active creation of infrastructure to support punk bands and other forms of creative activity” (226). For cities like Edmonton and Winnipeg, a sense of community can bind individuals and institutions within a music scene, where campus stations, record stores, venues, and so forth, support and sustain music-making. However, as interviewees from these cities pointed out, there can be limitations for career-minded artists who wish to move beyond the local scene and establish themselves beyond its borders.

Music communities and scenes are interwoven in the ways that each are understood as integral to music in geographic and social spaces. The idea of community is fluid and can be fraught. It is easy to romanticize “community” against the notion of a major music industry monolith. It might be a vehicle of exclusion by which certain artists or industry intermediaries are welcome to participate at the expense of others (exclusionary practices that might be oriented around taste, class, race, gender, and so forth). Alternatively, an idea of community might conjure ideas of participatory and collaborative music making or cultural production (CitationMayes 19). Despite myriad meanings, it is necessary to emphasize the fact that community is a term that helps musicians make sense of their everyday lived realities and experiences as artists and, throughout our interviews, a number of key characteristics can be said to define or describe community-led values in the context of music-making. Within a larger framework of music scene studies and community-based music-making practices, our interviews with independent musicians in Canada point to three themes for which we might focus attention and energy in our thinking about how we might restructure or reimagine the music industries in the streaming media era. These include: Sustainability for musicians (livelihood), sustainable infrastructure, and transparency and community.

Sustainability for Musicians

A “sustainable music career,” of course, is defined differently by individual musicians. For some, the ability to play music and to tour without losing money is the goal. For others, the aim is to make a living wage off of playing and recording music. As one artist claimed, the desire to “put art in the world that I think is meaningful” often means having to make money to survive and to sustain one’s self. Another defined a sustainable career as “paying rent, paying my bills, having a decent standard of living … being able to afford to take care of my child.”

There are a number of obstacles to achieving a sustainable career. Many interviewees stressed the toll that music-making and the increased pressure to carry out a wide variety of tasks and jobs related to their career can have on their mental health, a hazardous situation explored by CitationGross and Musgrave. Sarbit explained, “All I wanted to do is make music. I didn’t necessarily want to run a business at the same time and take care of the people in it.” There is a tension between spending time writing music and the need to be on social media “talking about it,” as Felicitas said, echoing a dynamic that Baym isolates. Sahunta indicated that a larger “obsessiveness” with social media “is pretty toxic to mental health” and can involve a “constant comparison cycle.” Fraser emphasized the mental health struggles that come with being an artist, “because you don’t run on a paycheck … if you can work nine to five but still get no money. You can go do a show and still not make money.” Commenting on the common narrative of the need to tour to earn income in today’s music industries, Samson said that heavy touring ruined a lot of personal relationships.

The standards and structures set by the music business can be difficult to conform to and they often work against one’s artistic sensibility. Arlo Maverick, an Edmonton-based hip hop MC, commented on the increased pressure to release singles more regularly but that he sees himself as an album artist: “I want to take time to create a body of work.” He added that there have been rapid, significant changes in the nature of an artist’s creative practice and labor over the last decade or so: “all of a sudden it’s like, ‘Okay, if you want to be on our site, you need to pay us money’” (see; CitationBurton). At the same time that artists are coming to rely on corporate social media platforms for marketing themselves, the companies behind these platforms are increasing the barriers between fans and artists. Jared Salte of alternative-pop band the Royal Foundry said that both Facebook and Instagram have changed their algorithm and that there is now a financial cost required for fans to see the news or updates that the band is sharing.

The entrepreneurial nature of a musician’s creative labor reflects the variety of income streams that any one artist might require in order to maintain, or work toward, a sustainable career. Royalties from radio, money from sync and licensing deals, adjacent income (such as working a second job), and streaming music royalties are some of the most frequently cited income streams according to interviewees. Some artists said that airplay on the CBC’s radio services provided reliable royalty cheques. A number of artists said that their royalties from being played by the satellite radio service SiriusXM were amongst their highest sources of income. When the American services XM Radio and Sirius Satellite Radio were licensed in Canada (both have since merged to form SiriusXM) a number of Canadian channels were required, including CBC music channels, like Radio 3. Sound Exchange, which deals in royalties from streaming radio like SiriusXM, was said to pay more than most other royalties. Fraser explained that one large check from Sound Exchange and performance rights was notably significant, which helped to “pay bills, build credit, buy a new car … pay for my own recordings” and to “even pay [her] sister’s bills and help [her] family out more.” Brown has been participating in songwriting circles “to build up a library of songs that could potentially work for placements or song licensing.” Far from a dying medium, radio is in fact the lifeblood of many independent musicians’ careers.

A less reliable source of income has been per-stream payments from streaming music services like Spotify. There is a paradox between the dominance of these services and the pressure artists feel to have their music featured on playlists and the accompanying payouts that artists receive. As Salte says, “Over the past five years, we’ve seen our streams go up but our [streaming] income go down quite a bit.” Others have been slightly more successful, such as Sarbit who, after being featured on a playlist and generating nearly a million plays of one song, received around $4,000 (still a very small number considering the high number of streams). Shane Matthewson from noise rock band KEN mode said that “as far as new fans discovering us, it’s through Spotify playlists” and noted that one of their songs was on a Spotify metal workout playlist “and that’s our top streamed track.” While income from streaming is predominately negligible, some have found ways to profit off of the opportunities that a playlist feature or listener data affords.

Sustainable Music Infrastructure

Infrastructure, which includes institutions and resources that are essential for music-making (venues, cultural intermediaries, and local media), is a key component of a music scene and the broader environment that enables a musician to remain in a city or town. There is the issue of sustaining venues themselves and ensuring that there are places for artists to perform, but also ensuring that live music venues and festivals are accessible and inclusive spaces. Spencer Heykants from Edmonton rock band Counterfeit Jeans explained, “It’s good to see that a lot [of venues] are adopting inclusive space policies. So people who sometimes wouldn’t feel comfortable going out to see a show now feel that they’re welcomed.” Issues of accessibility, inclusivity, and equity shape not only the audiences’ experience of a performance but also the artist experience. Samson highlighted the example of inequality with artist payouts. He recalled an instance when he and partner Christine Fellows “both played the Winnipeg Folk Festival two years apart with exactly the same band and she got paid a third of what I got paid.”

While venues may be the most obvious place where musicians and audiences come together, a range of spaces and places like studios, radio stations, print weeklies, and record stores combine to support local music-making in important ways. Many interviewees noted that campus radio stations have been helpful as a “pipeline to get your music across the country especially because touring can be prohibitively expensive, given the size of this country” (as said by Jed Gauthier of Counterfeit Jeans). Sahunta traced the success of one of his albums to campus radio: “It started charting on campus radio across Canada, there were a couple of stations in the UK that picked it up. … and then I started getting offered some really cool gigs out of that.” Campus radio remains an important local media outlet for independent artists, particularly as the trend in commercial media has been to delocalize. A notable benefit of the campus sector is that artists can submit music to stations directly, as opposed to having to pay for an aggregator to distribute music via a streaming service like Spotify. Edmonton is served by the University of Alberta’s CJSR-FM and Winnipeg has CKUT-FM at the University of Winnipeg and CJUM-FM at the University of Manitoba, but artists typically submit music to stations across the sector, hoping for national airplay. Local media and journalists are strong advocates for local musicians, but this is a resource that has nearly disappeared from music cities in Canada and beyond. Other components that artists indicated were missing or lacking within the broader framework of sustainable music infrastructure were “more community organizations … like a resource centre” to help figure out things like contracts (CitationSarbit); and “mental health aid for artists is like massively needed” because music is “such a personal endeavor that if things don’t go well, it can get dark” (CitationSarbit). Fraser was frank about her struggles with mental health and trauma, and mentioned the support provided by the Unison Benevolent Fund. Tragically, she died by suicide shortly after talking to us.

Transparency and Community

A lack of transparency across various components of the music industries was a recurrent issue expressed by interviewees. A veil of uncertainty permeates an artist’s relationship with people and things that are essential to their careers, including, but not limited to, labels, contracts, grants, and playlists. Klippenstein mentioned that one label was “reluctant to even tell us what the records had sold” and that there was very little sense of what money was coming in from streaming music services. Brown cited the importance of transparency when dealing with contracts but that it is expensive to hire an entertainment lawyer. She noted specifics like ensuring that artists know what Sound Exchange is and how it works and that there are “differences between performance royalties here in Canada versus the performance royalties in the US.” Brown added that “for the next album that I’m putting out, I made the decision to hold on to my masters. … it’s a huge income stream if you do get your songs played on the radio or satellite radio.” In another compelling example, Samson has used his platform to inform audience members at live shows about how much he has been paid that night: “I feel like it’s important to do because if we want justice and diversity, there needs to be transparency about who’s making the money, because it’s usually not the artists.”

Another recurring theme among our interviews was the privileging of community and care over commercialism. Rather than profit-seeking and entrepreneurialism, a community of care has been central to the livelihoods of artists and to the notion of sustainable music infrastructure. Artists often advocated for a community of care, built upon mentorship, resource sharing, and community networks. Arlo Maverick is an advocate for mentorship and he offers grant writing support to others: “I’ve sat on juries before, I’ve written grants before, I’ve written grants for the artists. … And with that information, I don’t look at it from the standpoint of, ‘Okay, this is mine, I don’t want anyone to have it,’ I look at it from the standpoint of, ‘Okay, who needs to know about this?’” Fraser also emphasized the importance of teaching and educating within a community. “I teach [children and others] how to write a song and people are seeing the value in me trying to build a bridge for other Inuit artists,” she said, “because I don’t want them to suffer like I did.” A notion of community also came through in certain comments about productive relationships with respect to the task of booking shows and tours. One artist explained that after touring for over five years, “I feel at home in so many places and Canada feels like a neighbourhood to me and it’s really lovely and I am so cared for by so many different places and it is so loving.” Samson has found that outside ideas about community defined only by music itself, he has found comfort in a music community that was also a “political music community” which means feeling as though he is a part of “a real community that’s not based on competition.”

Conclusion: Recommendations for Canadian Music Industries

“Water running along a pavement will readily seep into every crack,” Ed Yong writes about the failure to contain the COVID-19 virus; “so, too, did the unchecked coronavirus seep into every fault line in the modern world.” Though the plight of musicians may not rank among the most immediate concerns of the pandemic, the diversity of our musical culture could well be another victim of the virus. COVID-19 led to an overnight collapse in the live concert market, the livelihood for many performing artists. But as this article has sought to demonstrate, Canada’s music industries were already riven with fault lines, through which many of its most promising musicians were falling through the cracks. The task before us is to rebuild in a more sustainable fashion.

In response to this rebuilding effort, our research project – driven by a methodology employing both “top-down” political economy and “bottom-up” ethnography – aims to offer recommendations from both perspectives as well. In a separate article, we document our efforts advocating for musicians in government copyright consultations and the need for antitrust and anti-monopoly action, as well as public streaming infrastructure (Selman et al., forthcoming). In the following, we draw from suggestions our interviewees made, synthesized with our own thoughts on the political economy of Canadian music, to offer three main recommendations, which balance a need for near-term reforms and long-term transformations. We advocate for the implementation of policies, structures, and practices that,

prioritize a broad and diverse class of working musicians, not just superstars;

use government support to achieve sustainability for both an artist’s livelihood as well as for music infrastructure that is not monopolistic; and

shift emphasis away from market-oriented, profit-based, commercial conceptions of Canadian music and toward a community-based, care-informed model.

Musicians have different needs and aspirations; becoming too reliant on one aspect of the music industries or on one income source can be detrimental to supporting the careers of varied artists. It is with this point in mind that our recommendations hope to rethink and revitalize the ways that artists are supported in Canada.

Supporting a Diverse, Working Class of Musicians

“If music becomes something that people just do as a hobby,” Gauthier laments, referring to the difficulties of a working musician, “you’re going to lose a whole bunch of voices in music because you’re just going to have the people who can afford to pursue music careers.” As non-Canadian multinational companies dominate the industry, government support through grant money is of vital significance, a key point that was raised by all of our interviewees. Thus, we strongly encourage increased funding at the municipal, provincial, and federal levels. The metrics for which artists qualify for grants should be continually restructured so as to allow for a wider diversity of artists to receive support, with less focus on discriminatory markers such as “proper grammar.” Struggling artists should be supported by means-tested grants and mental health support should be a priority. Provincial music organizations, like Alberta Music and Manitoba Music, were, for the most part, described as helpful resources that are, as described by Felicitas, “really good at connecting the dots, especially across Canada.” Given some of these barriers and the larger instrumental turn in arts funding, some musicians shared ideas about how to reform the granting process. Salte pointed to an Alberta Foundation for the Arts grant that covers living expenses “for while you’re working on something” as a “great, forward-thinking” grant because “that’s a very real need for an artist.” Others indicated that application systems could be more user-friendly and that, in some cases, juries could be more diverse. The grant-writing process itself could be subsidized, as its current process favors the educated and well-connected. Furthermore, positive working relationships between federal and local organizations can be a productive way to decentralize the music business in Canada and strengthen musical and cultural activities in localities across the country. Bolder yet, this patchwork of government funding initiatives could be replaced with a universal basic income (UBI) for working musicians who can demonstrate some minimal level of productivity and fandom. As Wright envisions, a UBI would create “a massive transfer of resources to the arts, enabling people to opt for a life centered around creative activity rather than market-generated income … creat[ing] a potential alliance of poets and peasants” (74). Imagine the vitality and diversity of Canadian music if independent musicians were not saddled with constantly hustling in a winner-takes-all corporate contest.

Cultivating an Equitable Music Infrastructure

Nurturing a healthy music culture requires more than just ensuring musicians are being paid. There are a number of opportunities for rebalancing equity within Canada’s complex music infrastructure. Taking inspiration from the campus-community radio sector in Canada, which is nonprofit and regulated so as to program Canadian, local, and varied music, we imagine productive scenarios in which certain live music venues might operate as nonprofit organizations and be committed to the showcasing of diverse and independent music. These venues could be connected to campus-community stations and serve as a reliable venue for radio programmers and station volunteers to organize shows for local and touring bands that reflect the station’s music programming. Just as commercial radio stations with more than $1,250,000 in annual revenue make financial contributions to Canadian Content Development (including FACTOR, Musicaction, and the Community Radio Fund of Canada), profitable and high capacity live music venues and sports and entertainment complexes could help to finance smaller, nonprofit music venues (particularly if a large entertainment complex receives public funding to be built, such as the Rogers Place arena in Edmonton). With more funding, campus-community stations could expand their partnerships with local and student-produced media to cover local and diverse music. Given the dominance of music listening on Spotify and Apple Music in Canada, and the increasing importance of playlist inclusion, we need regulations that mandate a wider variety of Canadian artists on playlists for the major streaming companies operating in Canada. There is a long history of cultural policy in Canada that serves to promote and protect Canadian culture, particularly against American cultural exports (CitationSkinner and Gasher; CitationArmstrong), such as the aforementioned Canadian content regulations, and there is much debate as to how this can play out in digital and streaming media. The Liberal Party’s proposed Bill C-10, for instance, seeks to promote Canadian content in digital and streaming media but it has been met with opposition and concerns about user rights and net neutrality (CitationMcKelvey). Nevertheless, algorithmic bias toward certain, mostly corporate content already exists; now is the time to consider how to effectively implement local, regional, and diversity mandates.

Moving beyond a Profit-based Conception of the Music Industries

Considering the onslaught from transnational media conglomerates and financialization, the diversity and vitality of Canadian music will not only require continued government support for arts and culture, but bold action, such as financial reform, cultural protectionism, and antitrust enforcement. Reform that would truly help independent Canadian musicians would strike at the corporate power held all across the cultural industries: record labels, publishing, touring, radio, tech platforms, and financial firms. As a rash of new research indicates, antitrust reform and tax increases are increasingly necessary to tame the power of monopoly in the new gilded age (see CitationDayen; CitationTeachout). The commercial culture facilitated within this transnational corporate atmosphere is stifling Canadian music and our interviews pointed to this plight. MacPherson said that “we need to try to take a step back from the notion that commercial viability is the best way to achieve our collective goals”; instead, we should focus on ways to “create a culture of creativity, of imagination, of celebration, of our uniqueness and less about competing on the market to get some sort of weird market share that’s already flawed and broken.” One anonymous artist feared a dystopic future if the current incentives of the streaming-based music economy continue: “it’s not sustainable. … we’re going to end up with no art to stream.” As tech platforms become more entrenched in our daily and cultural lives, their designation as a utility becomes more appropriate. A public, nonprofit approach to streaming should be considered, one that privileges community, care, and sustaining working musicians over non-Canadian corporate profit. Capital City Records at the Edmonton Public Library is one example of a digital public space that could be used as a model. The library provides local artists with an honorarium to make their music available for anyone with a library card, with artists retaining rights to their content which can still be shared and sold anywhere else. This example highlights ways that listeners, artists, and cities can be connected through noncommercial, public spaces. Moreover, such a space is able to make use of the internet and digital technology in a way that partially circumvents unfair power dynamics and concentration in the media industries. With more local public libraries joining this initiative, a national network of local, library-based streaming music services presents an exciting alternative.

COVID-19 is an unmitigated disaster for Canada’s music culture. The songs that will never be recorded and the live concerts that will never be staged are a dramatic loss for our nation’s heritage. But as it has been in many sectors, the pandemic is also an opportunity to rethink what is most essential and how our structures do or do not support those essential workers and values. New space has opened to consider alternatives to ossified, unequal industries. To Yong’s metaphor of the pandemic being like water that has seeped into every crack of the modern world, we can add Leonard Cohen’s: “There is a crack, a crack in everything/That’s how the light gets in.”

Acknowledgments

This article results from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada funded Cultural Capital Project. Thanks also to William Northlich, Anna Dundas-Richter, Maria Khaner, and Daniel Colussi, who provided research assistance and insights into the project. Thanks to all of the artists who generously gave their time to be interviewed but especially Kelly Fraser, beloved Inuk singer, who was gracious and giving, and will be sadly missed.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andrew deWaard

Andrew deWaard is an Assistant Professor of Media and Popular Culture at the University of California, San Diego and the coauthor of The Cinema of Steven Soderbergh: indie sex, corporate lies, and digital videotape (Columbia University Press/Wallflower, 2013). His current project examines the financialization of film, television, and popular music. Email: [email protected]; ORCiD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2323-2106.

Brian Fauteux

Brian Fauteux is Associate Professor of Popular Music and Media Studies at the University of Alberta. His book, Music in Range: The Culture of Canadian Campus Radio, explores the history of Canadian campus radio, highlighting the factors that have shaped its close relationship with local music and culture. Email: [email protected]; ORCiD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2165-8605.

Brianne Selman

Brianne Selman is the Scholarly Communications and Copyright Librarian at the University of Winnipeg. She studies trends toward oligopoly in both music and scholarly publishing, as well as the importance of fair dealing and public domain works for critical and creative works. Email: [email protected]; ORCiD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1768-2250.

Notes

1. “Independent” is a fluid and imperfect category but we use it throughout this article due to its currency as a term describing creative autonomy, a low-to-middle income status, and/or music making that operates at some distance from the major record industry. However, there are many downsides to the term independent, such as its relation to taste and distinction, its occasional meaning as formal experimentation, its lack of precision (see CitationDryhurst for a discussion of why the term “interdependent” captures the ambiguity of much music-making), and its history of being privileged by scholars in contrast to mainstream music released on major labels (see CitationMall). Furthermore, the term independent has become increasingly imperfect as many independent artists and labels maintain limited partnerships with major labels and the variety of income streams that artists engage with today complicates the independent-major binary. Our use of the term is also based on our interviews, in which musicians discussed their conflicted independence: not charting on major hit charts but may have (or had) moderate radio airplay (likely on public, campus, or satellite radio); relying on government grants for support; maintaining a tenuous relationship with labels and intermediaries; and who are laborers not only in making music but in other adjacent areas like promotion, social media management, tour booking, and so forth. We considered a number of alternative terms (non-superstar musicians, low-to-middle income musicians, working musicians, community-based musicians, and musicians struggling to achieve a living wage), but found all of them imprecise as well. See CitationHesmondhalgh (“Indie”) and Bennett and Strange for further discussion of the term independent. Similarly, “music industry” is a slippery term and we aim to be specific about the many music industries (including recording, publishing, radio, live, licensing, and streaming), while still maintaining a broad perspective on what constitutes musician labor within a consolidating industry/set of industries. Furthermore, many musicians themselves, including our interview subjects, often imagine themselves in some sort of relationship with “the music industry.” See CitationHesmondhalgh (“Flexibility”), CitationToynbee, CitationFrith, CitationWilliamson and Cloonan, and CitationSterne for further discussion.

Works Cited

- Anderson, Tim. Popular Music in a Digital Music Economy: Practices, Problems and Solutions for an Emerging Service Industry. Routledge, 2014.

- Anon. Personal interview. 18 Dec. 2019.

- Anon. Personal interview. 24 Jan. 2020.

- Anon. Personal interview. 26 Feb. 2020.

- Arditi, David. Getting Signed: Record Contracts, Musicians, and Power in Society. Springer International, 2020.

- Armstrong, Robert. Broadcasting Policy in Canada. U of Toronto P, 2010.

- “Artist Revenue Streams.” The Future of Music Coalition, http://money.futureofmusic.org. Accessed 15 Aug. 2020.

- “Arts and Creative Industry Funding Structure Changed in New Alberta Budget.” Canadian Art, 31 Oct. 2019, https://canadianart.ca/news/news-roundup-arts-funding-cut-by-50-in-new-alberta-budget. Accessed 15 Aug. 2020.

- Baym, Nancy. Playing to the Crowd. New York UP, 2018.

- Bedford, Tyler, Jed Gauthier, and Spencer Heykants (Counterfeit Jeans). Personal interview. 27 Feb. 2020.

- Behr, Adam. “Cultural Policy and the Creative Industries.” The Routledge Reader on the Sociology of Music, edited by Kyle Devine and John Shepherd, Routledge, 2015, pp. 277–85.

- Bennett, Andy. “Introduction.” Music, Space and Place, edited by Sheila Whiteley, Andy Bennett, and Stan Hawkins, Ashgate, 2004, pp. 1–22.

- Bennett, James, and Niki Strange, editors. Media Independence: Working with Freedom or Working for Free? Routledge, 2014.

- Bliss, Karen. “Canada 150: Celine Dion & Shania Twain Lead Nielsen Music Canada’s Top Canadian Artists Chart.” Billboard, 29 June 2017, https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/7849410/Canada-150-celine-dion-shania-twain-nielsen-charts. Accessed 3 Sept. 2020.

- Brown, Colleen. Personal interview. 15 Feb. 2020.

- Burton, Christine Smith. “‘Playola’ and Fraud on Digital Music Platforms: Why Legislative Action Is Required to Save the Music Streaming Market.” Journal of Business & Technology Law, vol. 16, no. 2, 2021, pp. 387–435. https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/jbtl/vol16/iss2/9.

- Byager, Laura. “Spotify Just Released This Year’s Most-Streamed Artists and They’re All Male.” Mashable, 4 Dec. 2018, https://mashable.com/article/spotify-most-streamed-artists-male. Accessed 15 Aug. 2020.

- Canada. Parliament. House of Commons. Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage. Minutes of Proceedings. 1st sess., 42nd Parliament, Meeting No. 114, 2018.