ABSTRACT

This article analyzes norteño corporeality, or how bodies physically engage with norteño music and visually display norteño identities. Through a comparison of more than 75 mainstream videos, it explains how current norteño corporeality differs from earlier corporealities, why it differs from tejano ones, and why it strongly resembles those of gangsta rap. Using an interdisciplinary approach, the article focuses on the banal and the ordinary in musical performance; in so doing it shows how gender and race interact with and are affected by neoliberalism in the US-Mexico border area.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, I conducted ethnographic and oral-historical research on two linked dance crazes created by young Mexican Americans or Chicanas/os/xs, quebradita and pasito duranguense.Footnote1 Both genres fit within the universe of ranchero styles, music/dance that refers visually, lyrically, and sonically to notions of border-area rural life and vaquerismo, cowboy culture. Both also drew on the music of tecnobanda, a pared-down version of the traditional brass banda. Quebradita developed in Los Angeles in the early 1990s in a context of anti-immigrant sentiment that resulted in legislation like Proposition 187, which urged teachers to report possibly undocumented students, neighbors to report on neighbors. Duranguense emerged in Chicago in the wake of the new wave of xenophobia that followed the 9/11 attacks. In such contexts, loud music and fashion and attention-grabbing dance moves helped teenagers to claim public space, assert hybrid identities, and engage in group-building activities in times and places in which they had felt their voices to be silenced. While based on commercialized musics, these dance scenes had arisen organically, a grassroots response to challenging contexts that adapted mass-mediated expressive culture to local needs.

I have found that music genres tend frequently to be linked to particular performances of gender (see CitationHutchinson, Tigers), and while it has long been held that northern Mexican music (which includes música norteña per se as well as conjunto, tejano, ranchera, banda, and mariachi to some degree)Footnote2 is a sphere of machismo,Footnote3 many of my teenage interviewees felt their dance forms were quite egalitarian. Women necessarily played a big role in these crazes because they were partner dances, and dancers often described male and female roles as equal. On the one hand, some quebradita dance teams did perform moves explicitly aimed at demonstrating such equality, such as when the female partner would flip the male, rather than the more common reverse. On the other hand, in more commercial representations of quebradita, like the low-budget dance films produced in California in the 1990s, or like the later representation of quebradita in televised dance competitions in the 2000s, dancers performed more traditional gender norms.

More than a decade later, I wanted to follow up on this research with a new analysis of northern Mexican dance/music performance. My question was whether the physical use and visual display of the body in música norteña had changed in subsequent years due to changing gender roles. I term this kind of performance norteño corporeality, which describes how bodies engage with and express norteño music and identities. Based on my aforementioned belief that changes in musical genre are linked to changes in gender performance and vice versa, I initially hypothesized that broader societal changes would indeed have led to changes in corporeality. I tested my hypothesis by watching and analyzing more than 50 official music videos and videos of live performances of mainstream norteño artists and groups, including most of the top 20 Billboard Regional Mexican artists and songs from 2010–2015. For comparison, I also watched an additional 30 official and live tejano music videos.Footnote4 In watching these videos I watched for markers of norteño corporeality as well as their broader context, including the videos’ settings and narratives. My objective was not to describe exceptionally interesting works, or to investigate the performances ethnographically as I had done in earlier projects. It was to focus on the ordinary, even banal, performances of the mainstream – to focus on artists and videos that do not challenge norms but uphold or even help to create them. (For purposes of this article, “mainstream,” ordinary status was determined based on common music-industry markers of popularity, principally Billboard charts.) In accordance with CitationDiane Railton and Paul Watson, I found that music videos are an ideal way in which to track changing masculinities and how they interact with local, regional, and global spheres. In, CitationRailton and Watson’s words, each video presents a “specific geo-cultural masculinity,” but all videos are framed within the conventions of their genres and a globalized music industry. Because of this, music videos make “a range of local hegemonic masculinities available at a global level,” even as they “disguise the pernicious work of global hegemonic masculinity”–particularly its enforcing of heteronormativity and patriarchy–by exalting individual and local differences (125).

I did observe change, both in norteño corporeality and in musical sound, but it was not quite what I had expected. In these videos, I expected (or perhaps just hoped) to find an increasing use of dance coupled with an increasing presence of women and diminishing hypermasculinity, commonly termed “machismo,” for men. Instead, what I found was less use of dance, less of a presence for women, and perhaps even greater machismo for men than was the case at the time of my last research project involving norteño styles. And changes in musical sound in fact seemed to surpass those in corporeal deportment. In this article I will provide a typology of commercial norteño music videos and compare nine aspects of these videos. I argue that the changes observed can be explained by norteño’s increasing commercialization within the particular racial and social configurations of the United States. More specifically, I find that changes in corporeality are linked to the neoliberalizationFootnote5 of the border environment, a process simultaneous with the commercialization of music like norteño under the industry-created umbrella term of “Regional Mexican,” which corresponded to changes in the (racialized) gender identities norteño portrayed. Finally, I will conclude by placing my discussion and analysis into the present moment.Footnote6

Norteño Music Videos: A Brief Typology

Norteño is a form of northern Mexican music typically centered on the accordion and bajo sexto, a regional form of 12-string guitar, rhythms like polka and waltz, and especially the corrido, a kind of heroic ballad common in the border area. It is a close relative of tejano, although tejano more often features cumbia rhythms, synthesizers, and influences from U.S. American forms like rock. In spite of its name, which refers to northern Mexico, CitationCathy Ragland (194) has pointed out that norteño’s primary audience is Mexican migrants in the United States. For most of its history it received little airplay in Mexico, both because it is seen as old-fashioned and rural and because it refuses to “assimilate into either a Mexican American (i.e. Chicano or Tejano) or Latin American definition of popular music” (195).

These problems notwithstanding, norteño music remains a highly popular and influential musical genre in the U.S. Southwest. In music-industry terminology, it is now subsumed into the catchall category of “Regional Mexican,” a term I unpack further below. Norteño music videos, consumed via Internet, are today both polished and plentiful. Yet this abundance does not correspond to an increasing variety of gendered narratives or portrayals on the small screen. In fact, as I will show, an increase in corporeally expressed hypermasculinity and a foregrounding of image in the form of production values and of consumption in attire, setting, and possessions are changes that have accompanied a reduced diversity of gendered roles, and these changes have arisen in response to the genre’s commercialization and incorporation into the neoliberal society of today’s USA-Mexico border.

With few exceptions, mainstream norteño music videos come in two main and one minor types, which correspond to lyric content and form:

Stories about a Heterosexual Romantic Relationship

The imagery is of a couple, usually including the singer, during intimate moments: embracing, caressing, eating together, sleeping together. Often a misunderstanding or betrayal is involved, providing dramatic tension. Such scenes are interspersed with shots of the band playing. I call this type norteño romántico ().

Portrayals of Male Bonding

Another type of video shows few or no women at all, instead focusing on a group of men (the band or their proxies) drinking together, engaging in business activities (potentially illicit, as signaled by the frequently used shooting location of an airplane hangar and the occasional appearance of cops), or enjoying ranch life. When women do appear, they serve as status symbols or window dressing–for instance, demonstrating the band’s popularity by appearing in party scenes in bikinis or minidresses. The main song type is the corrido, so I call this type el corrido macho.Footnote7 We could also refer to these as homosocial videos, given the form of interaction depicted ().

Immigration

A third category is formed by the immigration corridos that depict male travelers undergoing hardships on their way to wage labor in the United States. Los Tigres del Norte, outspoken on immigration issues, have put out some of the best-known examples of this type, but they are not alone and such songs are indeed popular, as Caliber 50ʹs 67 million YouTube views (as of August 2020) of their 2014 tragic video hit El inmigrante demonstrate (). Immigration corridos have been more interesting to scholars, and the videos may have greater narrative and visual interest, but they are far less numerous than the other two types.

Figure 3. El inmigrante by Calibre 50 (2014) depicts another masculine narrative, one of the tragedies of undocumented migration. C. Disa Latin Music, a division of UMG Recordings Inc. Posted on YouTube by Calibre 50.

As can be seen, men are at the center of all these narratives, just as they are at the center of norteño musicking, even in songs that seem to address female listeners (i.e. in norteña romántica) and in fact quite literally at the center of the screen in the majority of the videos. All are strongly heteronormative.

Corporeal Dimensions of Norteño Videos

To address the issue of what kind(s) of masculinity appear(s) in norteño videos and begin my comparison, I want to distinguish between three parameters of bodily action:

Bodily Movement

A great deal of screen time in norteño videos, particularly in corridos machos, is devoted to men hardly moving at all. In fact, a surprising number of homosocial videos show the men only or mainly in a seated position, contrasting with live performances by the same groups. Both sitting and standing, however, norteño musicians in videos do move more than did, for instance, Los Tigres del Norte in their early movies. Interestingly, perhaps the most corporeally active musician in many recent videos is the sousaphone player, even though this instrument is the largest and heaviest. The most common movements are time-keeping ones, like bouncing in the knees or shoulders to the beat of the music.

Gesture

Whether seated or standing, the corporeal locus of activity in these videos is the upper body, the focal point of action being the often-emphatic gestures of the singer(s). In the early 2000s, I noticed an innovation appearing in duranguense videos: the use of hand gestures that resembled those one would see in mainstream hip hop. This trend has expanded. A particularly dramatic example occurs in the video for “Qué tiene de malo” (“What’s Wrong with That”) by Caliber 50 featuring El Komander, where emphatic gesturing is coupled with angry facial expressions and lyrics that assert, “I assure you that listening to corridos doesn’t make me a bad Mexican” (). In the video for “A la moda” (“In Style,” ) by Gerardo Ortiz, gestures also underline parts of the lyrics–for instance, when Ortiz points two thumbs backwards at his guardaespaldas (bodyguards) when they are mentioned or jabs his left wrist toward the camera when mentioning his Rolex de diamantes–but they also serve a rhythmic function as they almost always occur on the beat and frequently together with key musical gestures such as instances of stop time.

Dance

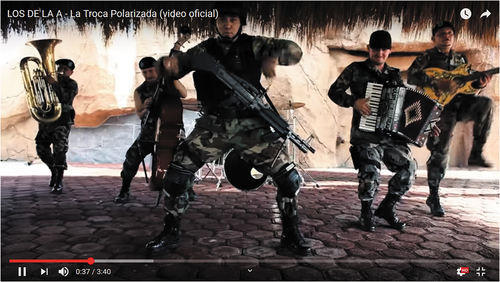

Few commercial norteño videos of this period show any dancing at all. This is perhaps surprising, since live performances of the music almost always include dancing audiences, and also because of the aforementioned, influential dance crazes in the region in the 1990s-early 2000s. Dance is one way in which women have always participated in the genre. Yet, aside from a minicraze called pasito Sotevó – after a cumbia by norteño group Los Vendavales from the town of Sotevó, Chihuahua–and a few videos with background dancing meant to indicate a party atmosphere, dance seems largely to have disappeared from norteño’s visual imagery, along with women themselves. This is true in all types of videos. A notable exception is a video by Los de la A titled La troca polarizada (“The Truck with Tinted Windows”), in which dance is used humorously. The lyrics describe how the singer’s red pickup is a magnet for women, causing them to behave scandalously. Here scenes of driving around with women are interspersed with ones of the band playing as they perform over-the-top moves like pelvic thrusts, rhythmic jogging, and high kicks – in some cases, while carrying assault rifles ().

Figure 5. Los de la A demonstrate their over-the-top dance moves in La troca polarizada (2014). c. Los de la A. Posted on YouTube by los de la A Oficial.

Bodily actions like these help define norteño corporeality. We can see that stereotypically “macho” or hypermasculine males are the ideal, with an avoidance of any gestures, movements, or contexts that would indicate softness. Even as the increasing kinetic activity level of performing musicians nods to the show-business requirement to visually entertain, the usual absence of both dance and women from central positions of videos seems to constitute both of them as threats to the protagonists’ masculinity. The vigorous, aggressive nature of the gesturing and dance moves adds to the impression that male bodily comportment needs to be policed in order to keep it from becoming too soft or feminine.

Such observations are a start. But further information can be gleaned from three additional parameters, those corresponding to visual symbols and their interpretation:

Imagery

I already noted that the vast majority of videos and song lyrics feature one of just two possible narratives. The visual imagery accompanying these narratives is correspondingly constrained. Norteño romántico is set in modern, wealthy-looking homes and urban restaurants; corridos machos are either given idealized rural settings or are placed in bars, nightclubs, or grandiose homes, such as in El Señor Iván by Enigma Norteño, where band members play poker and, later, their instruments in a heavily gilded and mirrored mansion even while singing to their “plebes” (). New cars and small planes feature prominently, such as in Ariel Camacho’s Entre platicas y dudas, which is set in a small airport’s hangar, as do cityscapes and scene-setting shots of Mexican landscapes.

Attire

Men in these videos either wear upscale casual menswear, often with brand names visible, or Western attire with little trace of the rasquachismo, an esthetic of glitz and pastiche often interpreted as tackiness (see CitationHutchinson, From Quebradita; CitationYbarra-Frausto), that characterized earlier trends. One sees satin shirts and blazers in coordinating colors, perhaps with a few sequins or an embroidered name to add bling, or jeans with casual plaid cowboy shirts and tasteful hats, perhaps with an elaborately tooled leather jacket. Women appear in bikinis or minidresses, seldom in ranchero styles, perhaps to indicate the musicians’ modernity. Gerardo Ortiz’s 2010 song “A la moda” (In style) describes the most important accessories: “In style and in good cars/and my boys are well-armed/well dressed in suits/and bullet-proof vests/Prada glasses and rosaries/diamonds all over” (this and all translations by the author). The video for this song () departs slightly from the usual homosocial formula, focusing on the singer sitting or half-sitting in a thronelike chair, cycling through various outfits, from ranchero, to upscale, to homeboy.

Gender Roles

The permissible range of characters/types enacted by men and women in these videos is narrow. Depending on the narrative type, men can portray the macho romántico, romantic male, or the macho bravo, tough male. Women typically have only one role: that of the mujer parrandera, the partying woman, who appears here not as a protagonist but rather as scenery (). In norteño romántico women also appear as love interests (), sometimes idealized, and sometimes as a partner in a “problem relationship” of which the singer hopes to rid himself.

Figure 7. Gerardo Ortiz shows off his attire with rhythmically punctuating gestures in A la moda (2010). C. Del Records. Posted on YouTube by chapo04.

Figure 8. Women shown as party accessories in De corazón ranchero by Voz de Mando (2012). c. Disa Latin Music, a division of UMG Recordings Inc. Posted on YouTube by Grupo Voz de Mando.

These six dimensions confirm the centrality of a masculinity that tends toward hypermasculinity in mainstream norteño music of the early 2010s while also beginning to show how this “machismo” is somewhat different from earlier iterations. One principal change is in how hard these videos work to give an impression of wealth and power. The wealth is conveyed through vehicles, settings, and attire; power is conveyed not only by the aforementioned bodily comportment but through the subordination of women and strict control over gender roles.

Musical Dimensions of Recent Commercial Norteño

The question then arises of how or whether musical sound works to either support or contest the other messages given through the videos, so I now examine three sonic dimensions.

Lyrics and Rhythms

As noted above, the two main lyrical themes are romantic disagreements and displays of hypermasculinity/machismo. These themes correspond to particular rhythms and forms. The male bonding and adventure narratives are typically, but not always, presented in corrido form. Such corridos often employ brand names of cars, clothing, and guns, as in the Ortiz example just given, “A la moda.” The rhythms used have not changed from earlier norteño: One still finds polkas, waltzes, and huapangos in abundance. However, the rhythms of huapango (a type of regional son which comes from northeastern Mexico and involves a sesquialtera feel, hovering between 3/4 and 6/8 meters) seem to appear more often and with more vigorous drumming and bass lines, while cumbias are not often heard in the sort of hardcore norteño dominated by narcocorridos, which has taken over the mainstream. It is more common to hear percussive accents that interrupt the musical flow (as in “A la moda”), evidencing a greater use of Afro-diasporic esthetics than in previous decades.Footnote8

Instruments and Sounds

Accordion and bajo sexto remain at the heart of the ensemble. Drum sets appear in nearly all groups. Some have electric bass. Beyond that, an interesting evolution has occurred: Numerous top groups have replaced bass or electric bass guitar with sousaphone, often played quite virtuosically.Footnote9 This new ensemble, which seems to be a nod to the popularity of banda music with its heavy sousaphone sound, is sometimes called norteño-banda or bandeño.Footnote10 In fact, many singers now perform and record with both bandas and conjuntos norteños, like Gerardo Ortiz, Tito Torbellino, and others. Formerly, the two ensemble types were more separate; this new development reflects both the music industry’s grouping of both styles under the rubric of “Regional Mexican” and the increasing role for star singers separate from particular groups, as discussed in the next item.

Many recent norteño videos also include sonic effects as a part of the soundtrack, particularly in introductions intended to set the stage for the music before it begins. For instance, the first 18 seconds of Entre platicas y dudas by Ariel Camacho feature a pounding drumbeat and running hi-hat taps that provide the backdrop for the arrival of three SUVs and a small plane (). The same amount of time elapses at the opening of Enigma Norteño’s El Señor Iván as low-pitched synthesizer sweeps build drama while credits roll over shots of a poker game and a young man delivers a letter from the protagonist’s father. And the first 30 seconds of Tito Torbellino’s Tus caprichos intercut lo-fi footage of a live concert with title screens dramatized with the addition of similar synth hits and sweeps. In each case, the sounds evoke high-octane action films, a hypermasculine genre.

Role of the Vocalist

Singing was not traditionally a part of banda music, given its natural loudness, but it has always been important in norteño. This importance seems to have only grown. Many singers are still instrumentalists as well, as is traditional in the genre. However, there are now many more men who sing only and do not play. Even those who do play an instrument frequently appear in at least part of their videos without their instruments. This portrayal allows for greater focus on musicians’ bodies and on their hand and arm gestures.

This brief comparison suggests that mainstream norteño videos ca. 2010–2015 work to further the hold of a commercialized and stereotypical machismo on the genre, not to challenge it. While queer performances of norteño corporealities do exist in the world (see CitationRivera-Servera 168–203), no such queering occurs in these videos. They do show change from earlier norteño music, but changes in imagery and corporeality are rather small. Musical sound appears to have changed more than these other aspects. To summarize, the main changes observed are these: Dance has largely disappeared; roles for men and women both have become constrained; attire has been upgraded and foregrounded, as have production values; brand names play an important role; the singer’s centrality has been amplified; gestures have become more emphatic; and finally, the genre has partially merged with banda, formerly a separate style.

Norteño Vs. Tejano Corporealities

Why these changes have occurred, and at more or less the same time, is a matter I will return to momentarily. Before I do, two other questions must be answered. The first of these is: Where are the women? A few have been active in conjunto music over the years, like tejana accordionists Eva Ybarra and Chavela Ortiz.Footnote11 Very few appear in modern, commercial norteño.Footnote12

One exception is Ely Quintero, a vocalist originally from Culiacán, Sinaloa, who mainly records banda but has also released some norteño and bandeño tunes. Perhaps it is Ely’s unusual position as a woman in this genre that caused her to title her third album Norteño Underground. Her song lyrics and videos portray her as a bad girl. In “Me hice mafiosa” (“I Became a Mafiosa”), she describes becoming a member of a cartel to attract the attention of a bad boy. The video La Cheyenne sin placas (“Cheyenne Without Plates,” note the use of a vehicle brand name) opens with Ely visiting the shrine of Jesús Malverde, the norteño folk hero sometimes described as a bandit saint or narco saint, and then taking off on a car chase while driving a truck with no license plate. Playing the role of a girlfriend of late drug lord Gonzalo Inzunza, she talks her way out of a sticky situation after the police pull the truck over and are surprised to see a female driver. In this video Quintero’s corporeality resembles that of male counterparts like Gerardo Ortiz, with shoulders keeping time and hand gestures punctuating the lyrics to the beat, although there are a few key differences: She frequently smiles (men seldom do), she is often shown dancing in place during instrumental sections, and the camera’s gaze is more expansive, often encompassing her curvaceous midsection or panning down to her feet. Other videos show Quintero engaging in a female homosociality much like that of norteño men–for instance, playing poker and drinking with a girlfriend in La pantera rosa (“The Pink Panther,” ). In contrast to male-centered videos featuring partying women as accessories or objects of a male gaze (), this one places the women at the center, and the men in the frame are simply talking amongst themselves, not disturbing the women’s fun even with a glance.

Figure 10. Ely Quintero enjoys a beer with a friend in her norteño-Banda video, La pantera rosa (2015). C. Independent / Orchard Music. Posted on YouTube by ELY QUINTERO OFICIAL.

Quintero’s performances seem modeled on those of Jenni Rivera, widely billed as the first female narcocorrido star, who recorded Regional Mexican albums and amassed a huge and very devoted fan base that has endured long after her untimely death in 2012. Rivera’s career began in norteño, but she later transitioned into banda, mariachi, and pop. Rivera did not release norteño videos or recordings during the years my study covers, so while she did not fall within my initial sample her influence is nonetheless sizable and she did perform with norteño backing in some of her live appearances in this period. For instance, a popurrí or medley of norteño-banda tunes at a 2012 concert in Monterrey, Nuevo CitationLeón, Mexico, was documented by numerous fans in YouTube videos. In these (e.g. Jenni Rivera –Popurrí Norteño (Editado)) one can see a norteño group playing at stage right while a banda stands at stage left, silent but for the sousaphone, all members swaying in synchrony to the beat. Out in front Jenni’s forceful vocal delivery is matched by grounded, subtle dance movements such as a hip or a shoulder shake on the beat inserted between verses, along with beat-conducting, hair flipping, and mimetic or pointing gestures with her free hand. Her body is often inclined toward the audience, creating an impression of intimacy. She exudes power and confidence. During a short interlude between numbers, she appears to drink from a glass of hard liquor as well as a water bottle. Her bodily comportment thus combines (stereo)typically male attitudes with moves that emphasize her more feminine bodily attributes. CitationDeborah Vargas describes the anomalous appearance of female/feminine performers in conjunto as “dissonance,” a creative way of visually and sonically disrupting the heteronormative and male-centered historical narratives of borderlands music. Rivera’s and Quintero’s play with and inversions of machista tropes might also be considered dissonant, but they harmonize well with other nonmainstream femininities, like CitationHalberstam’s “female masculinity” or the feminine tigueraje of some Dominican musicians (CitationHutchinson, Tigers).

While Quintero constitutes an almost unique exception in post-Rivera mainstream norteño, contemporary tejano music creates an interesting comparison and leads to my second question: Does tejano corporeality match that of norteño, or does it differ? Tejano is a regional genre that grew out of similar roots but later took a somewhat different direction in Texas than did norteño in northern Mexico and elsewhere on the border. In today’s tejano, one can hear not only numerous female singers, including the powerful trio of Los 3 Divas (Shelly Lares, Elida Reyna, and Stefani Montiel), but also – unusually – a number of female instrumentalists, from the almost all-female Grupo Imagen to timbalera Shelly Lares. I think it is not coincidental that this genre is dominated not by the corrido but by the dance-centered cumbia, a form that frees singer-songwriters from the rigidity of the corrido form and its associated themes, as well as their bodies from the rigidity of norteño corporeality. And this is true not only of women. Recent music videos show that even men working in tejano are able to portray a wider range of roles. Rather than being limited to the macho romántico or macho bravo, tejano men can portray devoted sons, brothers, and fathers (). Correspondingly, there are many more narrative possibilities in tejano videos: Singers can joke around and take on topics from modern love (Lucky Joe’s Muchacha bonita) to hanging out with the guys (Los Badd Boyz’ Vato Loco), grief (Sólido’s Inolvidable) to simply the music itself (Da Krazy Pimpz, Bomba y maracas and Cumbia de los Pimpz).

Race, Class, and Neoliberalism in Norteño

Why are men’s roles so constrained in norteño as compared to tejano, and why are there so few women in the former? Why have norteño music and corporeality changed in the particular ways they have over the first two decades of the twenty-first century? I believe that the norteño genre has become increasingly focused on a stereotypical machismo as signifier of mexicanidad and that this focus is primarily due to the increasing commercialization of norteño since the 1990s, itself a result of the neoliberalization of the border region. This case of increasing conservatism thus forms an interesting contrast to the English-language American pop-music videos analyzed by CitationCarol Vernallis, as she found these to be more often progressive, particularly in the realms of sexuality and gender dynamics (201).Footnote13 Tejano music has proven to be less widely marketable outside its home region and thus less attractive to major labels, which perhaps limited the influences of the neoliberal music industry on the style – it has never been subsumed under the “Regional Mexican” umbrella, and there have been few examples of “crossing over” into that market. The fact that it has maintained its unique regional identity has also allowed for a wider repertoire of gender representations and corporealities.

To explain further, it will be useful to look at the not-unrelated case of the commercialization of hip hop in the same period. Others have noted the striking parallels between the violence and hypermasculinity expressed in gangsta rap and in narcocorridos, ballads of drug trafficking (see, e.g. CitationMorrison). Today, those parallels extend far beyond narcocorridos, once an outsider subgenre and now a top seller, to infiltrate basically all commercial norteño production. Just as we have seen gender roles in norteño pared down to just a couple of stereotypes, so has the mainstreaming of rap whittled the formerly diverse genre down to one mainstream style and–as CitationTricia Rose argues–stripped away all possible masculinities except for the “gangsta” and the “pimp,” as well as all femininities but the “ho.” According to CitationRose, the “hypergangstaization” and “dumbing down” of hip hop coincided with its commercialization, from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s (3). As a result, mainstream American audiences tend to see only one-dimensional images of black youth, especially men, as violent and deviant, and thus, instead of understanding “rappers’ alienated, angry stories about life in the ghetto” as results and critiques of neoliberalism and structural racism, they instead interpret them as “‘proof’ that black behavior creates ghetto conditions” (5). Discourse about hip hop is thus part of a machine that creates devastating outcomes for Black and indeed all Americans, as anyone can see in current events. CitationKareem Muhammad extends this analysis to argue that nineteenth-century minstrel show characters have been recycled into contemporary mainstream hip-hop music videos in a way that advances neoliberal goals: The conspicuous consumer, he says, is a new incarnation of Zip Coon that spreads the neoliberal narrative of wealth’s accessibility to anyone with good financial sense. Such stock characters and narratives are so distant from hip hop’s radical roots, he says, that this mainstreamed rap should not even be considered the same genre but rather a new one with different goals: “minstrel rap.”

It is easy to note parallels here with narcocorridos and the Mexican-descent population of the United States. The social importance of bandit heroes, the narrative complexity, and the oppositional stance of traditional corridos have been reduced into the caricatures of smuggling lifestyles with attendant consumption now apparent in mainstream, commercialized norteño, while gender roles have correspondingly been narrowed down to the macho romántico, macho bravo, and mujer parrandera. The industry category of Regional Mexican, discussed further below, can then be considered a genre related to norteño but not identical to it and in fact even opposed to its political goals. Meanwhile, U.S. media attention to norteño has focused on narcocorridos almost to the exclusion of all else, producing a distorted picture of people of Mexican descent as excessively violent and unlawful. Such views – epitomized in Donald Trump’s racist comments about undocumented immigrants and his “wall” rhetoric – contribute to legislation that keeps migrant workers poor and disempowered, as well as to racist attitudes toward long-term residents and citizens of Latin American heritage. Such legislation in turn benefits U.S. businesses and businessmen like Donald Trump, who profit from cheap labor (see; CitationMorrison 379). The parallels between Mexican- and African-American music making, and musical cooptation, thus have roots as long as migrant labor itself.

One could even follow these links much further back in time–for example, by comparing the “treacherous woman” theme in 1930s-1940s blues, honky-tonk, and ranchera. CitationManuel Peña, for example, has suggested that listeners to all three genres felt resentment from class domination and transferred it the domestic sphere, the only one where subaltern males were able to enact dominance (58). CitationCathy Ragland similarly notes that in immigrant corridos the protagonist uses his machismo to “overcom[e] the obstacles of his low racial and class-based status” (174). This is the case even though, as CitationPeña notes, ranchera portrayals of treacherous women were a reversal of Mexican tradition, in which women were typically presented as faithful wives and men as the cheaters (58). Of course, there are musical connections between blues, honky-tonk country, and ranchera as well, and their audiences overlap. While this overlap was more apparent in the days before rampant commercialization and its attendant racialization (visible, for instance, in the early-twentieth-century-industry decision to create separate labels for “hillbilly”/White and “race”/Black records, a practice retained in the separate lists for country, pop, R&B, and Latin today), it still exists: Texas Mexicans often listen to both tejano and country, a fact made clear in George Strait’s inclusion of mariachi classic “El Rey” on his 2009 album Twang. At Strait’s 2010 concert at San Antonio’s Alamo DomeFootnote14 he could hardly be heard on that song due to overwhelming audience reaction. Similarly, all-women mariachi group Las Eréndiras de San Antonio played the popular country song “Redneck Woman” (which includes the line “I’ve got posters on my wall of Skynyrd, Kid, and Strait” as a redneck identity marker) at the 2009 Northwest Mariachi Festival for an audibly enthusiastic audience.

Comparison with the hip-hop case and a glance at a timeline show that the changes I have described here – increased hypermasculinity, reduced repertoire of gender roles, absence of women, display of wealth, use of brand names – all occurred during the rise of neoliberalism, made obvious in this part of the world through the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and its numerous aftereffects. Neoliberalization of the border was simultaneous with the commercialization of norteñoFootnote15 as a substyle of “Regional Mexican,” a category Billboard introduced in 1994–the same year NAFTA went into effect–to cover a miscellany of Mexican musics like mariachi, banda, norteño, tejano, grupera, duranguense, and more. (Today more than 60% of Billboard-reported “Latin” music sales are from this category [CitationAmaya 223].) The 1990s also saw the rise of commercialized banda, leading to the eventual emergence of bandeño. While partly rooted in earlier Mexican traditions, this style’s ascendancy also seems to correspond to market demands and marketing – if norteño is popular and banda is too, why not combine them to achieve a greater market share? What is interesting is that the “Regional Mexican” label has existed for more than twenty years but until recently did not apply to any particular genre. It was simply invented to facilitate the packaging of various styles that often shared an audience. Bandeño seems to show that this marketing convenience has actually had an effect on musical sound and practice. The invention of the label led to the creation of a new style of music that would fit it.

Norteño Music Videos, Neoliberalism, and the Latino Mediascape

Music videos can be used in highly individual ways. For instance, in his study of Moroccan-Dutch youth, CitationKoen Leurs found that “second-generation migrant youth dialogically negotiate the horizons of homeland, host country and youth culture as audience members watching YouTube videos.” Watching videos, including music videos, about and from their parents’ homeland “mediated home-making and nostalgic belonging” while helping them to create hybrid identities (241). In contemplating the building of identities in relation to social media and music videos, one can think of creative examples like homemade lip-sync or dance videos. U.S.-born or -raised youth of Mexican descent likely use social media in similar ways and draw on music videos as one of many cultural goods that can help them to build their own identities. Yet the videos I have described here, in contrast to more homegrown YouTube content, are commercial products intended to sell items like recordings, downloads, and concert tickets, along with allied products like fashion. Thus, they need to be studied and evaluated with a critical eye.

In the neoliberal world, citizens are recast as consumers, everything must be quantified, and esthetics are subsidiary to economics. Not even art can escape the need to generate profit, in a world where economic growth is seen as the ultimate good. Popular music is a particularly fruitful area for exploring the broader effects of neoliberal policies on society precisely because, as CitationDavid Harvey states, “the music industry is notorious for the appropriation and exploitation of grassroots culture and creativity” (36). In other words, this industry embodies in a nutshell the broader trend toward the privatization of formerly public goods. Yet the music industry is not singular but multifarious–in fact, calling it “the” music industry is misleading, given that multiple music industries exist around the world and even within the United States. Within the North American musical economy, Mexican regional music occupies a large market share, and it too is guilty of coopting and privatizing what formerly belonged to “the people”–in this case, the music of the border-area, Mexican-descent working classes.

The particular artists and musical styles I have analyzed here may not be known by name to most non-Mexican Americans, including Donald Trump. But even the orange-haired one is certainly familiar with the images they pedal: those of the swaggering Mexican macho, and particularly of the Mexican drug lord. Arlene Dávila reminds us that “neoliberalism is neither color-blind nor devoid of racism, even though it is predicated on its disavowal of racism – the attending view that the market constitutes the fairest space for upward mobility and that citizens who are entrepreneurial can reign supreme, unencumbered by the pettiness of race, ethnicity, and gender” (CitationLatino Spin 4–5). Neoliberal rhetoric would have us believe that all are capable of achieving the “American dream,” if they only would work hard enough. While immigrant corrido videos sometimes show the cracks in the system by depicting immigrants who live in poverty, the more numerous norteño romántico and corrido macho videos show their own version of the American dream – a life spent in luxurious houses, with shiny new cars and brand-name clothing to boot. For the most part, they uphold the neoliberal narrative rather than exposing its racist underpinnings.Footnote16 Success is quantifiable, and the measure of a song’s attractiveness is the (apparent) income of its singer.

CitationHoward Campbell (71) has described Mexican Regional music videos that glorify drug cartels and their violence. This glorification occurs in particularly explicit and disturbing ways in the case of the narcocorrido subgenre called the movimiento alterado (altered/disturbed movement), which I have not analyzed here, but also in the more mainstream offerings of Gerardo Ortiz, which I have.Footnote17 Such videos, CitationCampbell says, work in tandem with the narco-propaganda offered on narco web sites and propagated by mainstream social media users’ shares. They reflect the actual political economy in many parts of Mexico while also creating a dominated, demoralized population that can do nothing about the cartel’s dominance (73). Likewise, the capitalist values espoused in recent norteño videos help to create an audience that accepts them as normative and (presumably) does not question the tenets of neoliberalism, a situation that certainly benefits corporations more than their workers. CitationHector Amaya continues this line of thinking when he describes commercial singers like Ortiz as performing “violent identities” through their lyrical first-person narratives of drug-related violence, which create a “brand” through an illusion of authenticity (236–40).Footnote18 CitationAmaya believes that such claims of experiential authenticity appeal to “a population hungry for cultural experiences of power” (240). The feeling of power these videos offer can be experienced by the male norteño fan who himself adopts norteño corporeality in his daily life, or at least in his nightlife. Yet, deriving power from the performance of hypermasculinity alone creates a dangerous situation for women and the gender nonconforming. And the fact that this power is illusory must become only too apparent when the norteño fan exits norteño spaces and reenters “Anglo”Footnote19 ones, where even the President of the United States repeatedly describes him and his compatriots as “rapists” and criminals. These videos are part and parcel of larger trends in the Latino mediascape, since unprecendented growth in Latino media over the past decade has been accompanied by growth in anti-Latino/a sentiment (CitationDávila, “Introduction” 4).

Conclusions

This brief study suggests that neoliberalism affects not only the marketing of music but also how corporealities, musical sound, gender roles, and racialization develop with regard to particular genres and populations. This article thus responds to Javier CitationLeón’s call for “a more sustained and ongoing debate regarding the relationship between culturally expressive practices and neoliberalism” (135). Similar studies could be done for other commercialized genres by comparing corporealities before and during or after the dominance of the neoliberal world system in a given music style. Assembling a number of such studies would allow music and dance researchers to make more conclusive statements about how, exactly, neoliberal values and processes transform gender performance and expressive culture.

In the case of norteño music, commercialization led to a reduction of narratives and roles, bodily movements and gestures, and the kinds of imagery available to both men and women in music videos. And, while it may not constrain musical creativity, it does guide it into particular channels. Such constraints pose real problems because they lead to a vicious circle of negative media portrayals and self-policing of gender and racial boundaries that has real effects on intergroup relations as well as U.S. political rhetoric and government policy.

Can we hope for change in norteño’s limited and limiting gender roles? The neoliberal system will not disappear anytime soon. But, because commercialization encourages new trends and submarkets, we can certainly hope for new offerings. We can also hope that alternative channels for the dissemination of other forms of norteño will develop, as they have to some degree for tejano, hip hop, and other genres. There is reason to hope that mainstream artists may begin to speak out against these constraints. “Era diferente” (“She Was Different”), a 2015 Los Tigres del Norte song about lesbian love, took one small step forward by calling attention to norteño’s strong investment in heteronormativity. Parody acts like Los Pikadientes de Caborca (The Caborca Toothpicks, a Grammy-nominated bandeño group that began as a YouTube sensation) may point another way out ().Footnote20

Figure 12. Los Pikadientes de Caborca in La cumbia del río (2009). C. SME (on behalf of Sony BMG Music Entertainment. Posted on Youtube by pikadientesdecaborca.

If others follow Los Pikadientes in using their bodies and voices to satirize or comment ironically on norteño’s corporeal, sartorial, and gendered conventions – even while respecting northern musical tradition through adept playing of banda and conjunto instruments – they may help make this conservative, machista form of norteño corporeality so laughable that it will become impossible to perform it without at the same time questioning it.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sydney Hutchinson

Sydney Hutchinson is an ethnomusicologist and translator who has published three monographs, an edited collection, and many articles on Latin American and Caribbean music and dance for both academic and general audiences. She is also the translator of Rita Indiana’s novel Made in Saturn (Hecho en Saturno). Hutchinson has received fellowships from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Humboldt Foundation, American Association for University Women, American Folklife Center, Society for Ethnomusicology, and Dominican Studies Institute, and her works have received prizes including the Special Citation of the De La Torre Bueno Book Prize (Dance Studies Association), the Marcia Herndon Book Award (Society for Ethnomusicology), and the Samuel Claro Valdés Musicology Prize (University of Chile). An associate professor of ethnomusicology and Judith Seinfeld distinguished faculty fellow at Syracuse University, she now lives in Berlin and is research associate at Humboldt University’s Institute for Musicology and Media Studies. contact: [email protected]

Notes

1. Because of the contentiousness of identity labels, a short note on these terms is warranted. “Chicana” and “Chicano” are terms for people of Mexican heritage in the United States typically associated with an activist political and social consciousness. As I explained in my book (CitationHutchinson, From quebradita), many of my interviewees did not use the term Chicano/a to describe themselves, instead identifying as Mexican or Mexican American. For some, quebradita was a step on a road toward greater political consciousness, and they may have identified with the Chicano Movement later in life, but I elected to use the identity terms they themselves used at the time. I support the intent of the new term “Chicanx” to include those of nonbinary gender, but the fact that the term is an English-language intervention into Spanish-language discourse poses its own political problems, not to mention the fact that the word is unpronounceable in Spanish. “Chican@” still offers a good alternative – the final character combines -a and -o endings while not fully inhabiting either gender, and it can be read out in the same way as one would read “Chicana/o.”

2. A brief glossary for readers unfamiliar with Mexican music: Conjunto, mariachi, and banda refer to ensemble types. Banda in common parlance these days usually refers to banda sinaloense, large Sinaloan wind bands, although different brass-band traditions exist in many Mexican states. Bandas have been hugely popular since the 1990s, first through the trimmed-down tecnobandas emanating from Guadalajara and Southern California, and later in the original, massive Sinaloan bands with vocalists added as front men. Mariachi is the string-based music familiar as a “national” symbol of Mexico, featuring musicians in silver-trimmed charro suits and wide-brimmed hats playing violins, vihuelas (a four-stringed lute), guitarrones (Mexican acoustic bass), trumpets, and sometimes other regional stringed instruments. Conjunto refers mainly to the traditional border-area ensemble of bajo sexto (a regional 12-string guitar) and button accordion, often with string bass (tololoche) and two vocal parts harmonizing in thirds. In Texas, conjunto is also used to refer to tejano music more generally, a style whose audience, identity, and marketing apparatus are separate from those of norteño. Corrido and ranchera, in contrast, are song types that can be played by many ensembles. Corridos are narrative ballads that follow a specific poetic form and rhyme scheme and often feature current events or heroic tales about border bandits; they usually have a polka or waltz rhythmic accompaniment. Since the 1980s, narcocorridos – tales of drug trafficking – have been the most popular substyle. In contrast, rancheras are sentimental songs with a “crying” vocal quality, usually set in a slow four beats and often telling stories of romantic betrayal. Música norteña typically includes both corridos and rancheras; norteño groups usually add electric bass, drum set, and saxophone to the traditional conjunto. Música tejana (as noted above) is the Texas variant with its own local history and a greater influence from U.S. styles like rock, country, pop, and R&B; these days it more often centers on cumbias, the popular dance rhythm imported from Colombia, than on corridos. Except for the mariachi, all these ensembles are usually danced to. While mariachi repertoire once highlighted sones, regional dances featuring zapateado or percussive footwork, mariachis have since evolved into ensembles primarily meant to be listened to – even though some musicians and dancers are now working to reintroduce dance practices into the tradition. Music industry publications like Billboard lump all these styles and many others together into the category “Regional Mexican.”

3. Elsewhere (CitationHutchinson, Tigers 18–20), I have explained why “machismo” is a problematic and reductive term; in part because it is seldom used by Spanish speakers, scholars like CitationRamírez have argued that it is an externally imposed construct of the social sciences. Macho (male) and machista (sexist) are terms widely used in everyday life, but the first is a gender category and the second a critique of male behavior – neither does the work of machismo as a way of analyzing masculinity. In the book just referenced, I analyzed musical performance to uncover more complex and multifacted masculinities and feminities that belied the supposed primacy of machismo in Latin America. Here, however, I employ the term as a shorthand for the kind of stereotypically male-centered and machista behaviors and masculinities commercialized norteño supports and promotes. “Machismo” has also entered the English language as a less-academic synonym for hypermasculinity. Readers should not believe, however, that my use of the term in this specific way endorses the view that “machismo” is a common or universal Latin American characteristic. On the contrary – its presence here underlines the connections between racial stereotyping, heteronormativity, and commercialism in music that I dissect further below.

4. While in Spanish these genres are more frequently referred to with the feminine word forms norteña and tejana because of the gender of the noun música, in this article I will use norteño and tejano as these forms are more commonly used in English; the masculine adjective form also describes groups/grupos and male artists/artistas (and, as noted, the vast majority are indeed male). I capitalize the terms when referring to people and their identities but use lowercase for musical genres, as is standard in English. Norteño artists in my sample include Los Tigres del Norte, Los Huracanes del Norte, Los Tucanes del Norte, El Komander, Ariel Camacho, Los de la A, Gerardo Ortiz, Grupo Fernández, Caliber 50, Enigma Norteño, El Bebeto, Voz de Mando, Los Vendavales, Noel Torres, Tito Torbellino, El Tigrillo Palma, and Larry Hernández. Tejano artists include Pee Wee, Elida Reyna, Crystal Torres, Lucky Joe, Sólido, Shelly Lares, Grupo Imagen, Lucky Joe, Yvette Cruz, Angel González, Siggno, Los Badd Boyz, and Da Krazy Pimpz.

5. I use the term “neoliberalism” to refer to the stage of the global economy we currently inhabit. It is distinct from earlier forms of globalized capitalism because of how consumption, competition, and consumerism have come to define all human activity, as well as how corporations’ rights have subsumed those of individuals in supposedly liberal Western democracies and beyond. In a neoliberal system everything is quantified, and everyone is viewed first and foremost as a consumer. The effects of neoliberalism are perceptible in nearly every area of life and every field of action. Those of us who work in universities are now all too familiar with the recasting of higher education as a consumer product, and those who work in schools or have children attending them suffer through the emphasis placed on quantifiable test results rather than unquantifiable critical-thinking skills. In music, we see the pressure to produce what sells and the elimination of education programs that viewed music as a social good. Neoliberal transformations in music production intertwine with transformations in gender, race, and social class, as I have elsewhere described for Jamaica and the Dominican Republic (CitationHutchinson, Focus chapter 6). While some readers may dislike this term or prefer another, particularly because the root word “liberal” may lead to confusion regarding this system’s political leanings, “neoliberal” has become the most widely-used term to describe the world system to which I refer and to which all of the issues I here discuss are intimately linked. Using this label can be advantageous in that it pushes us to recognize how our current time (which spread globally since the 1980s, although it has roots in the 1930s and was first implemented in the 1970s) is qualitatively different from earlier eras. In my view, if we do not talk about and analyze neoliberal policies and their insidious effects, we allow them to remain invisible and give them more room to grow unchecked. Here I wish to expose how economics, race, and gender intersect in musical performance, as well as how all these are affected by neoliberalization.

6. I originally presented the results of my research at the Second International Conference on Música Norteña Mexicana held in Canton, New York, in 2015. This article is a revised and expanded version of that paper.

7. The term intentionally echoes Banda Machos’ 1999 album Los corridos de los Machos.

8. Rhythmic breaks are used to increase excitement, incite dancing, or even invite spirits into a space in numerous Afro-diasporic traditions, though they are known by different names: stop-time in ragtime, breaks in jazz, cortes in Dominican merengue típico, bloques in New York salsa, kasé in Haitian voudou, bomba or masacote in Cuban timba, to name just a few. CitationBarbara Browning has written eloquently of how the silences in samba inspire, even demand, movement (9–15). Dancers in other Afro-diasporic styles feel similarly (e.g. see CitationMahinka 174–78 on the importance of breaks for salsa dancers).

9. Examples include Ariel Camacho y los Plebes del Rancho, Caliber 50, Voz de Mando, and Tito Torbelli.

10. There is also a substyle of sierreño-banda, which takes the sierreño ensemble of two or more guitars (one of which may be a twelve-string) and bass, a style popularized in Sinaloa in the 1980s, but replaces the bass with sousaphone.

11. For more on women’s involvement in conjunto, and why they face obstacles in becoming instrumentalists, see CitationValdez and Halley. Also see CitationLimón for a discussion of Selena and how she used “good girl” narratives to avoid being thought of as a cantinera, an “easy woman” who hangs out in bars. Ventura Alonzo, the first performing female tejano accordionist, employed similar strategies, avoiding drinking and cantinas, already in the 1920s (CitationVargas 119–20). And see Vargas for in-depth discussion of women in tejano as well as the accordion’s connections to a heteronormative, working-class, tejano masculinity.

12. While numerous women have won awards in the Regional Mexican marketing category, almost none of them can be classified as performing in the norteño style. More often, they sing pop with a Mexican tinge, sometimes country, and sometimes grupera music that may include accordion. For much of her career Jenni Rivera (1969-2012), the best-known and probably most commercially successful woman in Regional Mexican, performed mainly with bandas or mariachis, leading her to be classified as a banda or Latin pop musician.

13. However, music-video research has more typically focused on the exceptional – particularly interesting and creative videos – rather than on the banal, a type of musical production that requires further research across the board. If CitationVernallis had chosen to survey top-40 music videos over a period of time, she may have found more instances of conservatism.

14. The Alamo Dome is, of course, named after the iconic 1836 battle of the Texan Revolution. Won by Mexican troops, it still serves as a Texan foundational myth as well as a centerpiece in white Texans’ anti-Mexican invective, and it has also been the subject of numerous songs, films, and other popular-culture artifacts urging Texans to “Remember the Alamo.” Thus, the stadium was a somewhat ironic site for this meeting of Texas Mexican and Anglo-Texan musicians and sounds.

15. The commercialization of tejano occurred in roughly the same period, though perhaps starting earlier. For instance, Guadalupe; CitationSan Miguel describes 1989-1999 as the “era of corporate involvement” for Tejano (2). It may be that we do not see exactly the same constraints on Tejano simply because its market remains a regional one, much smaller than that of norteño, which is popular far beyond the USA-Mexico border region.

16. One should also note that, while norteño music videos peddle an illusory feeling of masculine power to cultural insiders, the same music is also used by cultural outsiders to peddle other commercial products. Arlene Dávila has shown how U.S. marketers codify and caricature differences between Latino groups in order to simplify their marketing formulas. “A common example of this is the reduction of regional and cultural diversity to a matter of music preferences,” she writes. “Adjusting to local tastes and cultural needs thus becomes a matter of using tejano music for multigenerational, bilingual Texas, or rancheras or banda music for rural California, or a mix of salsa and merengue for the New York market – appeals that rely on particularized nationalistic associations that ironically negate the pan-ethnic pretenses of the generic Pan-Latino project” (CitationLatinos, Inc. 82).

17. Ortiz is on the Californian Del Records label, which produces the corridos enfermos (sick corridos) that compete with the corridos alterados produced by “Los Twiins,” Adolfo and Omar Valenzuela (CitationAmaya 235).

18. CitationAmaya also points out that these first-person narratives contrast with the early narcocorridos of groups like Los Tigres del Norte, which were typically related in third person.

19. While this term is problematic, particularly since not all of those to whom it applies are of English descent, it is nonetheless widely used in the Southwest to refer to White persons without Mexican or other Latin American heritage.

20. Los Pikadientes’ oeuvre deserves an article of its own. Among others, it includes their initial 2008 viral YouTube hit, “La cumbia del río” (a nod to Los del Río of Macarena fame through a cumbia that sounds like a drunken village party), 2009 norteña romántica parodies like “La tenía más grande” (“His was bigger”), their ironic cover of “Billie Jean” (complete with a heavily accented and comically cracked falsetto voice), and the 2018 “Sácate la nalga” (roughly, “Show me your butt”), which masterfully parodies the entire corrido macho video genre from the sound effects in the cinematic opening credits to the exaggerated focus on the male protagonists’ enjoyment at seeing women in short shorts. Unfortunately, the joke is sometimes lost on English-language journalists (see, e.g. the earnest review of Pikadientes by CitationBarteldes).

Works Cited

- Amaya, Hector. “The Dark Side of Transnational Latinidad: Narcocorridos and the Branding of Authenticity.” Contemporary Latina/o Media: Production, Circulation, Politics, edited by Arlene Dávila and Yeidy M. Rivero, New York UP, 2014, pp. 223–44.

- Barteldes, Ernest. “The New Regional Mexican Music: Authentic, Modern, and Here to Stay.” BMI, 12 Nov. 2009. http://www.bmi.com/news/entry/the_new_regional_mexican_music_authentic_modern_and_here_to_stay. Accessed 31 May 2020.

- Browning, Barbara. Samba: Resistance in Motion. Indiana UP, 1995.

- Campbell, Howard. “Narco-Propaganda in the Mexican ‘Drug War’: An Anthropological Perspective.” Latin American Perspectives, vol. 41, no. 2, 2014, pp. 60–77. doi:10.1177/0094582X12443519.

- Dávila, Arlene. Latino Spin: Public Image and the Whitewashing of Race. New York UP, 2008.

- Dávila, Arlene. Latinos, Inc: The Marketing and Making of a People. 2nd ed., U of California P, 2012.

- Dávila, Arlene. “Introduction.” Contemporary Latina/o Media: Production, Circulation, Politics, edited by Arlene Dávila and Yeidy M. Rivero, New York UP, 2014, pp. 1–20.

- Halberstam, Judith. Female Masculinity. Duke UP, 1998.

- Harvey, David. “Neoliberalism as Creative Destruction.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 610, 2007, pp. 22–44. doi:10.1177/0002716206296780.

- Hutchinson, Sydney. From Quebradita to Duranguense: Dance in Mexican American Youth Culture. U of Arizona P, 2007.

- Hutchinson, Sydney. Tigers of a Different Stripe: Performing Gender in Dominican Music. U of Chicago P, 2016.

- Hutchinson, Sydney. Focus: Music of the Caribbean. Routledge, 2019.

- Jenni Rivera - Popurrí Norteño (Editado). Video. YouTube 5 Jan. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HZGIfUJInZk. Accessed 13 Feb. 2022.

- León, Javier. “Introduction: Music, music making, and neoliberalism.” Culture, Theory, and Critique, vol. 55. no. 2, 2014, pp. 129–37.

- Leurs, Koen. Digital Passages: Migrant Youth 2.0–Diaspora, Gender and Youth Cultural Intersections. Amsterdam UP, 2015.

- Limón, José E. “Selena: Sexuality, Greater Mexico and the Song-and-Dance with Hegemony.” Etnofoor, vol. 10, no. 1–2, 1997, pp. 90–111.

- Mahinka, Janice. The Musicality of Salsa Dancers: An Ethnographic Study. 2018. City U of New York, PhD dissertation.

- Morrison, Amanda Maria. “Musical Trafficking: Urban Youth and the Narcocorrido-Hardcore Rap Nexus.” Western Folklore, vol. 67, no. 4, 2008, pp. 379–96.

- Muhammad, Kareem M. “‘Pearly Whites: Minstrelsy’s Connection to Contemporary Rap Music.” Race, Gender, and Class, vol. 19, no. 1–2, 2012, pp. 305–21.

- Peña, Manuel H. Música Tejana: The Cultural Economy of Artistic Transformation. Texas A&M UP, 1999.

- Ragland, Cathy. Música Norteña: Mexican Migrants Creating a Nation between Nations. Temple UP, 2009.

- Railton, Diane, and Paul Watson. Music Video and the Politics of Representation. Edinburgh UP, 2011.

- Ramírez, Rafael L. What It Means to Be a Man: Reflections on Puerto Rican Masculinity. 1993. Rutgers UP, 1999.

- Rivera-Servera, Ramón H. Performing Queer Latinidad: Dance, Sexuality, Politics. U of Michigan P, 2012.

- Rose, Tricia. The Hip Hop Wars: What We Talk about When We Talk about Hip Hop – And Why It Matters. Basic Civitas Books, 2008.

- San Miguel, Guadalupe. Tejano Proud: Tex-Mex Music in the Twentieth Century. Texas A&M UP, 2002.

- Valdez, Avelardo, and Jeffrey A. Halley. “Gender in the Culture of Mexican American Conjunto Music.” Gender and Society, vol. 10, no. 2, 1996, pp. 148–67. doi:10.1177/089124396010002004.

- Vargas, Deborah. Dissonant Divas: The Limits of La Onda in Chicana Music. U of Minnesota P, 2012.

- Vernallis, Carol. Experiencing Music Video: Aesthetics and Cultural Context. Columbia UP, 2004.

- Ybarra-Frausto, Tomás. “Rasquachismo: A Chicano Sensibility.” CARA, Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation. Exhibition Catalog, edited by Richard Griswold Del Castillo, Teresa McKenna, and Yvonne Yarbro-Bejarano, Wight Gallery, U of California, 1991, pp. 155–162.