ABSTRACT

Spotify offers users powerful algorithmic recommendations and hybrid “algo-torial” curation at scale. In this paper we argue that juxtaposed within this data-driven platform, is the power of human stories and networking. We investigate the experiences of 10 Australian musicians through semi-structured interviews, asking how they navigate the Spotify for Artists interface. By attending to the experiences of the artists themselves, and their use of the Spotify for Artists platform, we explore the human stories that flow within this socio-technical music streaming network, arguing that stories, like data, have an important role and value in this context.

Introduction

Historically presented as the “end” to piracy, music streaming has created new opportunities for musicians to distribute their music and connect with fans. The lower barrier to entry for musicians enabled by the platform has led some within the public discourse and academic debate alike to make claims of Spotify as a democratizing force between artists and the music industries (Brusila et al. 3). On the other hand, there is a perspective that sees music streaming platforms as powerful gatekeepers and intermediaries that reshape music practices whilst continuing to perpetuate longstanding inequalities within the music industries (Morris, “Curation” 456; Prey et al. 85).

There are competing narratives about what Spotify is and how it has affected the music industries and artists. The recent Netflix-produced 6-part miniseries The Playlist tells the fictionalized story of Spotify’s inception from the competing perspectives of six key people: founder Daniel Ek; Sony record label executive Per Sundin; the CTO of the company and known as “the coder,” Andreas Ehn; “the lawyer” Petra Hansson, who brokered licensing deals with the major labels; the “money man” and co-founder Martin Lorentzon, and, finally, offering the artist perspective, fictionalized musician Bobbie T. The miniseries is based on the book Spotify Untold written by Swedish investigative journalists Sven Carlsson and Jonas Leijonhufvud. A clear tension dramatized in the series concerns the definition and understanding of what Spotify is or should be for these different actors: a music company (with responsibilities to artists), a media company (selling advertising space and user data), or a free streaming platform to allow for universal access to music and content.

Spotify’s self-produced podcast Spotify: A Product Story shares an ostensibly insider’s history of Spotify, offering advice to budding entrepreneurs and product managers, and sharing how they “defeated piracy”, almost single-handedly. A similar David and Goliath story is invoked in The Playlist with Spotify going up against the music label giants and Silicon Valley tech companies. In Spotify Teardown, Eriksson et al. offer an alternative history of Spotify with its roots in piracy as a cultural and political movement in Sweden. Vonderau has argued that Spotify is best understood not as a music company, but instead as a media platform whose activities sit at the nexus of finance, advertising, and music (5; see also Prey, “Locating”). Kiberg and Spilker posit a new phase of streaming with Spotify’s proclaimed “audio first” strategy, which positions the company as distributor of audio-visual content, rather than simply music (157).

Many researchers, journalists, and artists alike have raised issues to do with streaming services, especially as they increased their market share to 65% of recorded music revenues in 2022 (IFPI). Researchers have investigated music streaming services’ role as intermediaries (Webster et al. 139), including their gatekeeping functions (Maasø and Spilker 306) exerted through their influential and powerful playlists and the datafication of music and users (Prey, “Knowing Me” 12; Drott 246), as well as claims that streaming services and their recommender systems homogenize music taste (Pelly), and do not appropriately remunerate artists (Mühlbach and Arora; O’Dair and Fry 70). These issues are certainly valid and worth exploring, though, as Nowak and Morgan argue, these perspectives may emerge from different ideas or narratives about what Spotify is (a media company, a platform, music company), and thus what Spotify should do (65). Whichever of these competing narratives prevails has ramifications for Spotify’s responsibility to rights holders and artists, as well as shareholders, advertisers, and users.

With these competing stories about Spotify as a backdrop, this paper aims to gain insight into the artist’s perspective by investigating how 10 Australian musical artists perceive, use, and interact with Spotify and the Spotify for Artists (S4A) interface. S4A is a back-end platform specifically for artists that offers metrics, data, and insights about their music and audience. Key S4A features allow artists to edit their public profile, to track metrics and to pitch songs to human editors who curate Spotify’s large body of editorial playlists.

This ontological debate about Spotify and its role in relation to artists is visible in the ways cloud-based, on-demand music companies are described more broadly. Variously described as Music Streaming Service (MSS), Digital Service Provider (DSPs), and Music Streaming platforms, the lack of consensus on what to call entities like Spotify, Apple Music, TIDAL, and so on speaks to the multitude of perspectives and approaches to their impacts. As is the nature of algorithmic platforms (Gillespie 348), Spotify positions itself as a neutral, data-driven service or platform (Nickell 49). Known for its powerful analytics, as well as acquisitions of discovery and music intelligence companies such as Tunigo and The Echo Nest, Spotify promotes itself as offering experiences and means to navigate seemingly identical catalogs (Hracs and Webster 242). These editorial experiences are driven by both human and algorithmic knowledge and data, in what Bonini and Gandini call hybrid “algo-torial curation” (“First Week”).

As Hesmondhalgh points out, some of the issues raised with music streaming, and leveled against Spotify and MSS, are in fact enduring issues from the music industries (7). For instance, the business of commodifying music which began with the commercialization of sheet music in the early 20th century (Wikström 66), the enduring tensions between making art and playing the game (Nowak and Morgan 65), as well as long-standing issues with remuneration for rights holders (Hesmondhalgh 4; Towse 1462).

Though many of these issues are not new or directly caused by the development of music streaming (Baym 26), we agree with Wikström (66), Arditi (302), and Prey (“Locating”), who argue that music streaming has certainly transformed the distribution and consumption of music, as well as music industry dynamics and economics at scale. We argue that these enduring issues are newly (inter)mediated at an unprecedented scale on MSS, making them relevant to investigate. For instance, issues to do with visibility and exposure for artists are not new, but the mechanisms by which artists are made visible are—through algorithmic recommendation and automated curation, as well as “algo-torial” curation by humans at scale (Bonini and Gandini, “First Week”; Webster et al. 139). Both algorithmic and human-curated editorial playlists hold a gatekeeping power over which artists are made visible through programmed listening, and those made invisible (Kjus 61).

Although data is an incredibly powerful resource within the music streaming network (Colbjørnsen 1272), we argue that stories also have a unique position within this socio-technical arrangement. We take stories in this context to encompass several dimensions of artists’ experiences: stories told by artists, stories about data, and stories as data. We investigate stories from the perspective of Australian artists, as they attempt to make sense of streaming dynamics through stories, as well as the stories they tell about their work. Stories are also important to Spotify as can be seen in their insistence on the story as crucial to pitching, their use of success stories to promote the platform as a force for stardom, as well as the corporate and brand stories they tell through their podcasts and advertising. We conducted interviews with 10 Australian musicians, as well as undertaking a close reading of the S4A interface. We complemented this with an analysis of Spotify company documents, marketing materials, and podcasts, and offer insights into the experiences of musicians as they navigate music streaming services.

Background

Approaches to studying music streaming have proliferated in the last decade as researchers and journalists seek to understand the effect of MSS on individual consumption, distribution, and algorithmic culture more broadly. Gaining access to proprietary data and software is a particular challenge, but worthwhile nonetheless (Bonini and Gandini, “Field”). There have been many different approaches to the “black box” of music streaming, such as Eriksson et al. who staged interventions into the Spotify system itself (7), or Bartlett et al. who used terms of service agreements on Spotify and Tinder to infer functionalities of algorithmic recommendations (4). Taking Spotify’s Twitter account as a proxy for Spotify’s agenda to explore their longer-term corporate strategy, Prey et al. found that Spotify has been promoting its own branded playlists over other content since 2012 (85).

Democratizing or Gatekeeping?

Many researchers have explored the gatekeeping role of MSS. For instance, Morris calls MSS “info-mediaries” that optimize content and moderate audiences (456). Maasø and Spilker identified six “hybrid gatekeeping mechanisms” that are enacted through music streaming services that account for “the streaming paradox” (306), which they argue perpetuates a superstar culture despite the availability almost all music. The gatekeeping power that MSS wield is exerted in several ways, such as via editorial curation. Playlist editors at MSS curate playlists and filter through pitched songs to create listening experiences for users. With some of the top playlists having hundreds of millions of monthly listeners, these editors hold immense gatekeeping power (Morgan, “Revenue” 35). Eriksson describes the playlist as container technology, in which editorial playlists are logistical packages to transport music and music data (415). She argues that they move around music as goods and services, making music calculable in the process, and influencing visibility and popularity. Given the superabundance of content on MSS, curators and playlists become essential to the distribution and visibility of music (Fleischer 256), as well as the harvesting of data about users and capital accumulation through advertising (Meier and Manzerolle 556).

Algorithms and automated processes of curation are also positioned as gatekeepers, enforcing what Nieborg and Poell call “regimes of visibility” (4288). Webster et al. (139) and Seaver alike have argued that we should see music recommender systems on MSS as powerful socio-technical cultural intermediaries. Users across a range of platforms, including MSS, must find ways to contend with algorithmic curation in order to remain visible, and often seek out information and strategies on how to do so (Cotter 9). Through such algorithmic processes and automated features, music data becomes optimized according to an algorithmic and platform logic in what Morris describes as cultural optimization (“Music Platforms”).

Focusing on the algorithmic related artists feature, Tofalvy and Koltai conducted a network analysis case study of connections of Hungarian metal bands on Spotify. They argue that this feature perpetuates or mirrors existing inequalities in the music industries, especially through label and international connections. Prey suggests that we should not only see power as coming from within the platform, but also see the platform as embedded within its context (“Locating”). Like Eriksson, he positions playlists as central to power moving relationally through the network. Thus music has a data value within the streaming network (Colbjørnsen 1282), rather than solely a cultural or commercial value (Morris and Powers 106). In the next section we survey some of the research that focuses on the artist perspective on music streaming services.

Artists and Music Streaming Services

Much MSS research has investigated the user experience of listeners: for instance, Hagen’s crucial work on playlisting behaviors (“Playlist” 625), Siles’s exploration of genres as social affect (2), and Freeman et al.’s investigation of listeners’ experiences of music recommendation. As the other side to this invisible interface, there is a smaller but still growing body of work that addresses the artist, musician, or music industries perspective (Maasø and Spilker 306). Baym et al. explored the experiences of artists using MSS metrics and how that informed their decision-making and strategy (3481). This research moves away from the “simplified tale” of positioning media workers as victims of power. However, their findings do suggest that those within the music industries that possess the most resources still achieve more success. Similarly, Hagen explores the role of data literacy in the music industries, and the potential democratizing force of artists with access to metrics (“Datafication” 14). Baym et al. found that such metrics were useful for administrative and strategic tasks (3481); however, they argued that datafication creates a divide between those who are data literate, and those who do not have the digital skills or knowledge to leverage these metrics.

Metrics ostensibly offer some level of transparency through democratizing access to data previously inaccessible to artists and managers. We agree, but also temper this with concerns around the power asymmetries and lack of transparency to do with algorithmic recommendation and algo-torial curation (Ferraro et al. 13). We focused on Australian recording artists, rather than management or label-level responses to metrics. Though we did discuss strategies for success, our focus was more on the experience of navigating the data-driven S4A platform, and less on the decision-making and business marketing strategies which have been explored elsewhere.

Critiquing the democratization discourse, Barna explored how digitalization of music has impacted musical careers in Hungary from a feminist perspective, arguing that it perpetuates long standing inequalities in the music industries (63). deWaard et al. combined an ethnography of Canadian musicians with a study of the political economy of the Canadian music scene to offer compelling insights into the power dynamics in that region.

We build on these previous studies into the artist perspective on music streaming, focusing on the experiences of Australian artists using the S4A interface. We contribute original insights about the role of stories within the data-driven system of music streaming, detailing recording artists’ perspectives on power dynamics within the Australian streaming context. Though there is a wealth of literature that explores narrative and storytelling in other contexts, rather than the content of stories, we explore how stories are valued within the socio-technical music streaming context. Our focus is on stories as data and the stories told about data and metrics. Data is never raw and the ways that people tell stories about and through data matter (Gitelman and Jackson 2). The metrics made visible by MSS are constructed through algorithmic and corporate logics, as well as through use. From this lens, we explore stories through the perspectives of artists, across several dimensions. Like Morgan we focus on the Australian context, and in doing so we add to a growing body of geographically specific research (noting a particular concentration in Norway), which emphasizes that music industries are unique and regionally specific (deWaard et al. 253).

Methods

To investigate the Australian artist perspective on music streaming, and the user experience of using S4A we conducted semi-structured interviews with 10 Australian musicians. They were recruited as musicians and key informants who used S4A. We focused on recording musicians rather than songwriters or other user groups and members of the music industries, such as managers, though these groups do certainly use S4A. The interviews lasted between 45–60 minutes. The interviews were conducted online via Zoom for two reasons. Firstly, this research was conducted in 2021 while there were lockdown restrictions in place in many states in Australia (particularly in Victoria where some of the artists and the researchers were located). Secondly, the interviews were conducted online so that artists could be invited to screenshare and take the researcher on a tour of their S4A interface. Taking its cues from elicitation techniques (Barton 179), this allowed participants to narrate their experiences using the interface, pointing out features and metrics that they had used, found useful, or did not like. This also served as a visual cue for participants, prompting them to share unexpected insights.

The interviews were semi-structured and followed a set of questions; however the researcher allowed for participants to “fill in the blanks” (Robards and Lincoln 720) encouraging the discussion of areas of interest relevant to the participants themselves (deWaard et al. 20). Questions were focused on participants’ use of the S4A interface, their experiences with using the features and metrics, as well as questions related to their perspectives on and experiences with music streaming within the Australian music industries. As this research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, many of the artists were in lockdown, and this affected their ability to tour and record, among other key activities. Though the focus of this research was on S4A, many discussions centered on, or returned to, pandemic-related issues. shows the participants’ demographic information, as well as the way that they described their work. The participants often had several jobs and roles within the music industries, and most would be described as professional musicians. We have included information about whether they were signed to a label or independent, as well as the number of song streams of their most “popular” song on Spotify at the time of the interview.Footnote1 We acknowledge the unfortunate gender skew in the sample. We endeavored to recruit a more diverse sample; however, given access challenges, especially during pandemic lockdowns, we used snowballing as access allowed. Though this is representative of the unfortunate gender skew within the Australian music industries, it is imperative that future research should include a more gender diverse sample.

Table 1. Participant table with demographic, professional, and song stream information.

The interviews and screenshares were video recorded, and the audio transcribed. We analyzed the resulting data by employing the six stages of thematic analysis (Terry and Hayfield 29). We complemented the interview data with an analysis of the Spotify For Artists website, with a particular focus on documents, articles and tools related to artist advice, as well as a close reading of the Spotify produced podcasts, NerdOut@Spotify and Spotify: A Product Story. The interviews and close reading of the S4A interface and website highlighted several key experiences which we explore in the next section: the power of “the story,” gatekeepers, and streaming challenges.

Findings

In this section we present insights from the interviews around four layers of the musician’s experiences. First, artists’ perceptions of gatekeepers and the “dark art” of playlist curation, followed by their seeking information and strategies. Next, their use of the interface (and related challenges), and finally their overall thoughts on “making it” and success.

Gatekeepers and the “Dark Art” of Making It

For many, if not all the participants, the internal operations of music streaming platforms were opaque. This was due to a combination of proprietary algorithmic systems, varying digital literacies, and an acknowledgment among all the participants that the music industries and MSS are influenced by powerful gatekeepers. Some described the process of “making it” in the music industries and getting onto playlists as a mysterious “dark art” (P2, P3, P5, P6). There was a clear sense among participants that there were invisible power structures, power brokers, and barriers to “making it.” Some participants expressed resignation in learning about, understanding, and contending with algorithmic selection and the “dark art” of playlist curation: “It’s a pretty steep mountain to climb to actually make this work for me, to deliberately try and work the algorithm” (P6).

In the face of such uncertainty, participants looked to multiple sources for information and guidance. Many turned to the music community for advice and fellow musicians, curators, or managers were a common resource, asking “How do we get playlisted? How do we get better streams?” (P10). More commonly, participants tended to rely on knowledge gathered from years of working in the industry in various roles. Many of the artists interviewed would also use their own experiences as listeners on music streaming services to try to understand and comprehend the algorithmic and platform logic they encounter and contend with in their work. Finally, artists would use anecdotes from their own and other musicians’ experiences to understand and speculate how algorithms worked. All participants expressed at some point in their interview that getting playlisted could lead to success, but it was much less clear to them how to achieve that.

Several participants referred to editorial playlists (made by human curators) as like any other gatekeeper. Having had a lot of success on Spotify editorial playlists, as well as exposure through playlists from notable curators, P2 pointed out the power of those creating the playlists:

It’s so important for the success of our releases for it to be playlisted. And so whoever is deciding, whether it is someone who’s created an algorithm to best program music or someone who is personally curating Spotify playlists, they have an immense amount of power. And if they decide they don’t like this sound or what that music represents then, yeah, you find yourself with a gate shut on you. (P2)

Knowing the power of playlists, many participants had attempted to get in contact with Spotify and their curators. P8, like others, found it “impossible to get to talk to someone,” despite his running a label and being in a successful internationally touring band:

It’s all back-room stuff. With Spotify, the way I see it, is they don’t really have the capability to liaise and talk with every boutique label. They’re very limited. They just want to deal with Virgin Music, Australia. It’s incredibly hard to forge a relationship with Spotify. (P8)

From talking to their label and distributor, P2 found that the more radio play they received on internet radio stations like Worldwide FM, the more they were able to convince streaming services to playlist their tracks. The more streams and playlisting they got, the more radio play they received on larger stations like B.B.C. Radio, creating what they described as “a closed loop.”

The Australian music scene also had its own unique power structures. For instance, in all the interviews, national youth radio broadcaster Triple J was mentioned.Footnote2 Participants discussed how powerful Triple J is in Australia, being essential for breaking artists and for “exposure” (P8), not unlike the effects of editorial playlisting on Spotify. P5 explained that not receiving Triple J plays was extremely detrimental to an artist or band’s career and opportunities:

If you don’t get on Triple J, then you’ve got almost no chance of making good amounts of money and getting on the bills for these big Australian indie festivals that dominate the live music landscape for young people. (P5)

It’s clear that both editorial playlisting and radio programming (especially Triple J in the context of Australia) were seen by participants as powerful gatekeepers. Likewise, algorithms were seen to be influential gatekeepers that had the power to decide who made it and who didn’t. Like the “dark art” of getting onto editorial playlists curated by humans, participants lamented their lack of knowledge of how algorithmic playlists and selection on streaming services works. P3 described the algorithmic layer of music streaming platforms as a “completely unattainable other world.” In a somber metaphor that encapsulates the feeling shared among many participants, P1 said:

It almost feels like that would be me trying to predict the ocean currents and I don’t know anything about the ocean currents. So, I’m just on a boat and I will end up where I end up. (P1)

P4 articulated issues to do with popularity bias, meaning that algorithms (through collaborative filtering) will continue to emphasize and make visible those artists with the most listens, which increases exponentially:

How do the algorithms figure it out? How do you get to the top tier? Is it based on how many spins you’ve had? Therefore, you’ll be more likely to get into someone’s feed. And because you’ve got spins early, then you’re getting your fees. You’re getting more spins, so you’re getting more fees and then you’re getting more spins. (P4)

However, P9 presented a slightly more positive view on algorithmic playlists, viewing them as more neutral than editorial playlists:

I’d probably say that maybe the algorithmic playlists are better, because I would imagine that they’re based on what people actually listen to and want to hear as opposed to what playlists an artist has paid to be on or just knew the right people to get put on a playlist. (P9)

Spotify’s Advice: The Power of the Story

To understand how the algorithms and platform work, as well as gathering information on labels, distribution, aggregators and “who to talk to,” artists would turn to several sources for information. Some, who had managers or label representation would ask them. Several participants were independent, or self-publishing. To gain insights into algorithmic and editorial playlisting, they would do their own research, with many turning to Spotify’s wealth of advice on their website, or other industry sources. In the next section, we contextualize these quotes with some examples from Spotify documents and industry advice.

The S4A website has a large collection of tools, advice and information for artists and music industry professionals on its website in the form of highly-produced and animated videos, blog posts, as well as testimonials and success stories from artists. One feature that was important to users in this study was the pitching feature. This feature allows artists to pitch their upcoming releases to be considered for editorial selection. The pitch asks musicians for the genre, sub-genre, language, and metadata about their song, as well as a free-form section that allows artists to share “their story.” Spotify explains, “You can pitch one song from an EP or album release—so pick your favorite that best represents you and your story!” (“Playlisting”). Pitching is very competitive; according to Spotify only around 20% of pitched songs get playlisted (“Behind the Playlists”).

Across the wealth of S4A documents, videos, blog posts, podcast episodes, several key messages emerge. The main S4A advice to musicians is to share as much of their story, metadata, and social media content with the platform as possible. From there, there is an assurance that left to their expert curators and powerful algorithms, a musician’s music will get on to playlists and in front of fans. For instance, Spotify explains in a Q&A article about pitching songs to editorial curators: “We’re always looking to curate more music and artists in our playlists, so we really value the time you give and spend sharing your stories and songs with us when you pitch your music” (“Behind the Playlists”). The expertise of their editors is foregrounded, as in this explainer from their website: “Editorial streams are curated by Spotify editors with a keen ear for what moves listeners. They will listen carefully to pitched tracks and make data-informed decisions about what will resonate with fans around the world.” The focus is ostensibly on the music rather than the data, as seen in statements like, “Music speaks to us in more ways than numbers. We put listening first” (“Behind the Playlists”).

In their podcast NerdOut@Spotify episode entitled “Humans in the Loop,” the emphasis on humans over algorithms is apparent as they suggest “it has always been about more than the algorithms.” In this episode the host discusses how the cultural, genre specific domain knowledge of human curators is crucial to the success of playlists and recommendation, as humans understand musical genre boundaries in ways that algorithms do not. This privileging of the human among the complexities of machine learning and algorithmic recommendations is also evident in this image from Spotify website (), describing the automated process of recommendation, likening them to a “personal DJ:”

Figure 1. Screenshot from Spotify for Artists, “Made to Be Found,” explaining how recommendations are made.

The importance of the story was consistent across several Spotify documents and tools for playlist pitching. For instance, in the video explainer on pitching they advise, “share your story & what makes you tick,” as well as compelling artists to share intimate details about their release, with “don’t be afraid to go deep.” Likewise, this advice: “If there’s an interesting story around you and/or the song, please let us know. The music is key, but context is also extremely helpful to us” (“Behind the Playlist”). Across the Spotify for Artists website there are testimonials and success stories from artists who have used Spotify tools, features, or metrics “to make it” and rise through the “Playlist pyramid” (starting with less popular “feeder playlists” where the algo-torial process takes place (Bonini and Gandini, “First Week”). If the song does well it moves up through the playlist ecosystem to playlists with higher monthly listener numbers, and, therefore, has increased chance for success. shows a screenshot of testimonials from artists and their stories of “how they made it” using Spotify tools and features. Spotify promotes these success stories across their website to demonstrate the power of their discovery and pitching features.

Figure 2. Screenshot from Spotify for Artists website (“How they made it”).

The role of media coverage and social media engagement was also a key message for artists, with S4A suggesting that artists should drive traffic to Spotify playlists through their social media, and that media coverage should be used when pitching to demonstrate the success of a release. Of course, this also works in Spotify’s favor as it delegates promotional work to the artists on their own social media. This is reminiscent of the annual Spotify Wrapped feature, which functions as a global free marketing event for the company as users share their listening data on social media.

The use of the word story is ambiguous, as it can also mean an example of success (social media followers, radio play, etc.) that is, in itself, still data-driven. Overall, the power of the story is foregrounded on S4A websites and tools, as well as the importance of social media in self-promotion and engagement with fans. Within this complex socio-technical infrastructure, human connection and knowledge are important.

Despite a wealth of available resources like the examples describe above, P7 explains the lack of useful insights on S4A pages:

What do they say? “Get your songs on playlists.” They say that and I’m like, “Oh, okay. How?” They offer pretty generic, banal advice. It’s like, “Send your songs to influencers.” (P7)

A common frustration was the sense that the advice given would not actually lead to success or visibility, and there was a layer of influence and gatekeeping that was impacting the participants’ chance of success. P6 explained:

It seems to me like they keep on saying, if you do this and do this, you’ll grow your audience. I’m like, well, no. Clearly there’s some kind of magical handshake that I haven’t shook which is how to get anything to happen for you on these streaming services.

Faced with this perceived level of gatekeeping, merit was a common concern amongst participants, as well as a lack of transparency around how editorial or algorithmic decisions were made. “That’s my biggest critique of it, is that I wish that it was more merit-based. But how we get there, I don’t know” (P8).

Metrics, Metadata, and Streams

In the following section we focus specifically on the S4A interface. During interviews we asked participants to screenshare and take a tour through the interface, describing features that were useful and those that were not. The following screenshot () from the Spotify for Artists website describes the S4A dashboard, as giving the “full story” of an artist’s music:

The application of metrics for music management and business strategy has been explored elsewhere by Baym et al. and Maasø and Hagen. Instead, we focused on the experiences of musicians in using the interface, and their perceptions of the metrics. These studies demonstrate the usefulness of metrics and data for making tour decisions, such as the geographical data about listeners, which was echoed by our participants. Though our participants did mention or show many metrics, we have focused here on a few key metrics, given the scope of this paper.

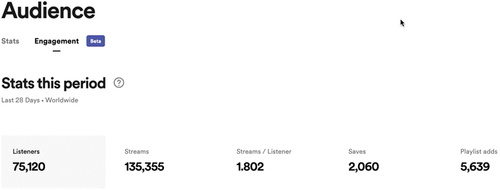

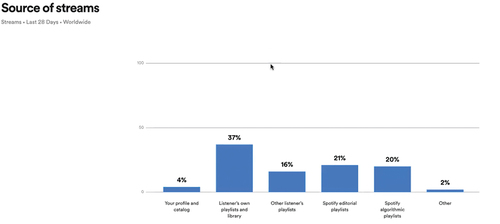

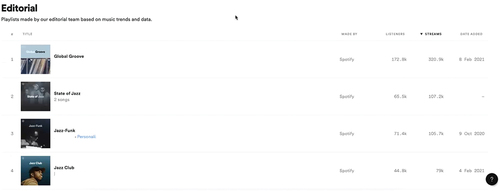

Compelling data points for many participants came from the audience tab which offers demographic data about listeners () and the source of streams (), which shows where users are listening to the music from the various playlist types (algorithmic, editorial, or personal). P9 interpreted this data to see if she was “actually creating fans.” For her these metrics were important to her as they reveal the “true” engagement with her songs—if a song moves from being listened to on an editorial or algorithmic playlist, to being in a personal playlist, this means that a “fan has been created,” rather than someone “just listening to her song in a café playlist.”

Figure 4. Audience tab showing listener data from P9’s Spotify for Artists Dashboard.

Figure 5. Source of streams data from P9’s Spotify for Artists Dashboard.

On the differences between stream sources, P2 said, “we always get the most streams out of our algorithmic playlists,” followed by strong editorial curation on and off the platform. P10 mentioned that they often “fell into [editorial] categories that were surprising,” meaning that they did not always feature in the genre or playlist categories that they felt represented them (see ). Though they were grateful for the placement and exposure, artists then had to make sense of these algorithmic or editorial decisions.

Figure 6. Source of listens from editorial playlists, data from P2’s S4A dashboard.

Whilst these metrics could be useful for the music business and marketing strategies, as well as giving some insight into listener or fan engagement, the same features could also elicit emotional responses. For instance, P1 described obsessively watching the live tally of “currently listening” users:

When I first released my first single, I just was obsessed with watching that thing. And it was really depressing because it’s never anything exciting. I can imagine if you are established, it would be really nice to see that, but a lot of the time is zero for me.

P1 said that she “didn’t ask for this” particular metric and wished she could turn it off. Others had no way of reading or interpreting the metrics, like P6 who said he just “looked at them blankly.” Some of the participants did not have enough data for certain features or metrics, which was disheartening.

Streaming Challenges

Participants also discussed challenges specific to music streaming, especially to do with metadata. For instance, P1 described having their music and artist profile entangled with another artist on Spotify by the same name. Similarly, P9, who is a feature vocalist, has experienced not being credited on several songs that she recorded, or not having her songs listed on her own profile. In both these examples—the artist identity entanglement, or the missing songs and credit—there were significant implications for artists and their careers. For P9, music not displaying on her profile was problematic for future opportunities with labels and venues. Some of the songs she is on have millions of listens, and labels look to these metrics. P1 said it was embarrassing to have her songs mixed up with another artist and didn’t want people to see that.

Both P1 and P9 struggled to rectify these issues and said there was no one to talk to. P1 was only able to change that because they had a chance meeting with someone who worked at a distributor that could talk to Spotify for them. P9, despite having millions of streams, has not been able to get those songs on her profile. She explained:

If I had the connection to someone that worked at Spotify that had a certain level of power, then maybe they would be able to do something about it. But to be honest, I’m pretty in the dark about it. It’s like just something that I’ve given up on.

Access and a direct human connection to Spotify was the only way she could see the issue being resolved. Another streaming challenge that was raised was the increasing pressure to make more content to “meet the demands of streaming” (P4). P6 explained further: “But if you’re mid-level or like us, you just have to keep coming out with music or you just get forgotten. The longer you leave it, it’s precarious with who stays interested.”

Finally, another issue raised by participants, and more broadly in the press is the issue of “Payola,” or the new feature being tested by Spotify called Discover Mode. This feature would allow labels and artists to choose songs to be algorithmically prioritized, in exchange for a lower royalty rate. P2 condemned this idea: “They announced that they were doing that, and that is egregious to the point where I was like, ‘This would make me stop using Spotify as a user.’ I can’t stop using it as a musician.”

Value of a Stream

A consistent issue for our participants, and artists more broadly, has to do with the economic value of a stream. As P8 said, “It’s no secret that the amount of money that they offer artists is pretty pathetic.” Participants acknowledged it is hard to ascertain the value of a stream compared to a physical product (for example a record or CD); however, there was an agreement that streams should mean more money for artists. Spotify has recently launched Loud & Clear on S4A which shows the profiles of different artist types such as Superstars, DIY, breakthrough, specialist, heritage, etc. (see ), in an attempt to provide transparency on how revenue and streamshare on the platform works.

Figure 7. “Meet the Artists” showing the Chart Toppers group of artists, screenshot from Loud & Clear.

Many participants acknowledged that in terms of fairness, even “superstar” artists or “chart toppers” weren’t making enough money. P8 explained, “Obviously, if you’re Tones and I, then you can make $12 million a year from Spotify. But on the side of Tones and I too, if it was fair, then maybe she’d be making like 20 bajillion dollars.” P6 believed that their nine million streams should translate to more money and that they “shouldn’t be stressing about cash.” For many, the number of streams didn’t necessarily translate to success in terms of revenue. However, there were other avenues for revenue and success mentioned by the participants such as live music, community radio, merch, and the sale of physical formats like records and CDs. In the reverse, success from these revenue streams and ways of connecting with the audience does not necessarily translate to streams for our participants. Indeed, P5 mentioned a disconnect between their live music performances and merchandise sales with streaming metrics and revenues from recorded music. P5 argued that Spotify (and music streaming more broadly) engenders an entitlement to listen to music for free, even at a very grassroots, local level. He suggested that it’s important to advocate for a culture of paying for music, and that a user-centric model of streaming could start to address this.Footnote3

“Making it” Now, and in the “Good Old Days”

When discussing music streaming services and the contemporary realities of the Australian music industries, there was a lot of reference to the “old days,” “old school,” practices and strategies, and mention of “back in the day,” which meant previous eras, previous formats and platforms, and previous practices. Myths, stories, and experiences about “olden days” helped artists to understand or rationalize their experiences with streaming and with the music industries. Comparing “then and now,” there was a common notion among participants that there was a “savviness” in the younger generation of musicians, that they themselves may not have had. This generally referred to tech savviness but could also mean business and marketing savviness. This notion also fed into some participants lamenting the fact that they had to self-promote and market themselves. P7 explained, “It’s like all of a sudden you have to become an entrepreneur and all this stuff. And it’s like, man, I just play guitar, what do you want from me?”

However, savviness on social media was seen by many participants as one route to success and popularity, which was echoed by Spotify’s own advice on self-promotion. As a counterpoint to these negative feelings toward social media and self-promotion, both P2 and P8 had both achieved significant success through employing digital skills. They spoke of the “old mentality” for how to make it through word of mouth and live shows. P2 and P8 both stressed that in the “olden days” there were greater barriers to entry into the music industry than now:

When people talk about the good old days, “we didn’t have an Instagram account, or I didn’t have to go on TikTok just to promote my music.” In those days, you had to have a label backing you; the music industry was so much more closed and impenetrable as far as I can tell. (P2)

Both participants saw the internet as a great tool in music promotion. P8 was especially enthusiastic about the role that social media had to play. He pointed to the fact that “back in the day” musicians had to be lucky enough to get placed on TV, in a magazine, or on the radio. Now artists (and their managers or publicists) can create their own exposure. Many participants pointed to the lower barriers to entry to recording and distribution enabled through streaming and the advance of technology in other areas of music (like software and hardware at home).

Stories about the “olden days” compared to now seemed to help artists to make sense of metrics and experiences within the platform. Likewise, these demonstrated conflicting ideas between participants about the value of digital skills, and the role of the internet in promoting music. What was clear was that among these participants there were different ideals about “making it” or what is important to each of these artists. For P9, it was most important to get people to come to a live show of hers:

Unless you’re creating fans that are going to keep coming back to you as an artist and like listening to your music and buying your merch and buying tickets to your shows, then you’re only really living half of the career of a musician if you’re just getting playlist plays.

As an example of the spectrum of approaches to success, P5 and P2 demonstrated very different outlooks. For P5, the importance of the live music scene and personal connections within the industry were most important:

Unless you are in the top 1% Australian musicians, you’re not going to do it. You’re just going to be chasing your tail trying to get this shit happening. I find that, for me, it’s been much more successful and much more sensible to just work on my craft as a musician. I’m a pretty easy person to work with, so thats been the way that I’ve been able to carve out a life as a professional musician.

P2, on the other hand, argued that the internet has been a boon for musicians, if they can equip themselves with the digital skills and use the platforms available to them. He said that the old equation of getting people to a live show and them telling a friend was not enough to translate to success:

It is an enormous expulsion of energy to go to a gig if you are only going to reach one person who then tells one person who then tells one person, whereas on the internet it’s so much easy to reach a far broader collection of people, with things like BandCamp and Spotify.

There were differing approaches to success and “making it,” though engaging with fans was the common goal among participants. For P8, social media was the best way of connecting with fans because they couldn’t rely on streaming, and they saw social media as a way to wrest some control back:

Social media is one example of stuff that we try to do to engage the audience, using tools that we just completely can do ourselves, because if we had put all of our eggs into the Triple J basket or into trying to get a Spotify playlist, we’d hit brick walls very fast.

Social media and live shows, as well as the use of digital skills for P2 and P8, were mechanisms to reach fans. For many participants, they would not rely on Spotify or Triple J for success.

Discussion

We began this article by contextualizing the competing narratives around what Spotify is and debates around whether it is a democratizing force for artists, and for the music industries more broadly. By investigating the user experience of Australian artists using Spotify and S4A, we aimed to contribute to these debates about Spotify and its effect on artists. Though all the musicians we interviewed each had a unique history and experiences within the Australian music industry, a number of themes were generated from the interviews, such as enduring gatekeepers, a lack of transparency around editorial and algorithmic decisions, and “making it” in the current digital environment. Like Baym et al., we agree that our participants were not “victims of datafication” (3481); indeed, many found meaningful insights that they could use or leverage in their self-promotion efforts. For others, streaming services were a necessary evil in terms of making their music available, though they did not view Spotify as a viable source of revenue. However, transparency was a consistent issue among all participants, and aligns with findings from other geographical studies (deWaard et al.; Maasø and Hagen). Despite the volume of metrics, the lack of transparency about how to secure the coveted editorial or algorithmic playlist spots, along with banal advice to “just get your streams up,” meant participants were at the behest of powerful gatekeepers.

Juxtaposed with Spotify’s powerful algorithmic and automated system, powered by data and machine learning, we argue that human stories, knowledge, and labor play a powerful role within this system. Building from the work of Webster (139) and Seaver, who see MSS as socio-technical systems, we argue that this begins with the humans in the loop on machine learning processes, and continues as artists contend with metrics, algorithms, and gatekeepers, demonstrating different digital literacies. In particular, we found that stories were especially important within this data-driven system, both for artists and for the Spotify platform.

For our participants, stories were used to make sense of algorithmic and editorial decisions, helping them to understand how the metrics shaped their music traveling through the system. Stories also helped artists make sense of these processes, aligning with the findings of Baym et al. On the other hand, Spotify entreats artists to share their stories, providing essential context beyond the data for their playlist editors, related to algo-torial processes (Bonini and Gandini, “First Week”). Likewise, stories of success for indie artists are used to demonstrate Spotify’s power to propel artists “up the playlist pyramid.” Virality and superstars were often heralded as success stories by Spotify, implicitly encouraging artists to continue trying. However, these high-profile viral successes on TikTok, Instagram, and Spotify are the exception, not the rule, which Masso and Spilker have described as the streaming paradox (306). For some participants who had individual tracks that had experienced “success” (more than a million streams), or even self-proclaimed virality, this one song still was not enough to live on.

These success stories are compelling, and there are arguments to be made that MSS and lower barriers to entry for recording have allowed for more independent artists to make money from their work (Hesmondhalgh 4; Nowak and Morgan 65). However, despite these lower barriers to entry, the superstar culture remains (Maasø and Spilker 306). Individual success stories belie the reality for most artists (Arditi 302), and we have shared a number of insights from the experiences of this group of Australian musicians. Baym et al. and Hagen (“Datafication” 14) have both argued that the limited transparency of metrics has allowed for more access, but only for some players. This was the same for our participants, those with greater digital literacy, or “savviness” as they called it, as well as greater connections had experienced more success through streaming.

A key issue for our participants was that of visibility, or what Taina Bucher more precisely calls “the threat of invisibility” (1164). There has always been a limited number of places at the top (Baym 26), and our participants acknowledged that. However, despite increasing access to distribution and to metrics, many participants felt that the lack of transparency around curation, as well as the presence of human and algorithmic gatekeepers were barriers to their visibility on the platform (Cotter 9). A lack of access to the platform for help with metadata issues and entanglements, as well as the perception that in order to achieve success and visibility, one needed any combination of insider access to tastemakers (editorial playlisters), contact with Spotify (either personal, or via a large enough label that had enough sway to have a meeting with Spotify), or access to resources to employ publicists and managers, or to pay for TikTok influencers to play their song over a video. From the perspective of the participants interviewed here, Spotify was seen as a gatekeeper, perpetuating long standing inequalities in the music industries (Tofalvy and Koltai), and perhaps creating new ones through its algorithms (Maasø and Spilker 306) and information asymmetries (O’Dair and Fry 70).

Despite their complex machine learning, algorithmic systems, personal stories, and connections were often crucial to participant’s success. With swathes of music and data being uploaded, stories become important contextual and marketing information for editorial decision-making. We argue that the power of human stories that flow within the music streaming network sits not in opposition to, but rather complements and adds complexity to discussions about the digitalization and commodification of music and the data value of music engendered by MSS (Morris and Powers 106; Nieborg and Poell 4288). We argue that like data, stories also have a value within Spotify, as well as providing value for artists in terms of sensemaking and self-promotion. Our investigation of stories within MSS complements the work of Seaver and Webster et al. (139), who encourage the reading of MSS as complex socio-technical algorithmic systems.

Our findings reiterate that there are layers of influence in the lives of these Australian artists, with music streaming services being only one layer. In the Australian context, radio broadcaster Triple J was seen as a powerful gatekeeper. Other context specific insights were the influence of community radio. Like Prey, we think it is crucial to consider the embedded markets and industries that Spotify exists within (“Locating”). Attributing issues solely to platforms and streaming services is reductive, though they do have notable influence as the mediators of these complex socio-technical and economic relations (Zhang and Negus 540). Indeed, MSS and other enduring music industry dynamics are characterized by a lack of transparency and power asymmetries that leave artists vulnerable. The diverse experiences of our participants point to both sides of the debate around the effects of music streaming that we introduced at the beginning of this paper, and we believe this is an area worthy of further investigation. Given the scope of this paper and the qualitative methodology, future research should look to broader demographics, perhaps also including other members of the Australian music industries. As always, insight into the streaming platform’s perspective would be a welcome and worthy avenue of research, though one that has been typically hard to access. Future research could also continue to explore the power dynamics, and geographic specifics of the Australian music industries within which MSS are embedded, such as the role of Triple J and community radio, as well as other music organizations such as Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA).

Conclusion

In this paper we have explored the experiences of Australian musicians’ navigating Spotify for Artists. Spotify is known for its powerful algorithmic recommendations, and automated and hybrid curation as scale. However, we contextualized this by attending to the human stories and experiences that flow within this socio-technical streaming network (Colbjørnsen 1272). There are competing (and also cooperative) stakeholders within the music streaming network, with unique agendas and needs. Several recommendations have been made as to how to improve these systems for various stakeholders, but particularly how to make them ostensibly better for artists. For instance, deWaard et al recommends the implementation of local, regional, and diversity mandates on MSS. This is an especially compelling recommendation, as the Australian government, through advocacy from music rights organizations such as APRA AMCOS, has just announced a new cultural policy that includes a quota for more Australian produced content on streaming services. The policy is starting with a focus on audio visual streaming, so it is not yet clear how this will affect music streaming in Australia. In another recommendation, Morgan suggests less pre-selection of content in the form of curation on playlists (“Optimisation” 164). Kjus, like many others, has suggested a more user-centric revenue model (69). Also valuable, are the improvements that our own participants suggested in this study, such as a push toward merit-based curatorial decision-making (as opposed to gatekeeping and personal networks), increased transparency, direct uploads to MSS (thus less need for middlemen and aggregators), increased revenue, and more mechanisms for audience-artist connection.

What these suggestions and improvements have in common is a shared view to wrest back some power and control for artists and users from powerful intermediaries, platforms, and gatekeepers—some new, some longstanding. Emerging from the insights we have shared here, transparency and explanations of algorithmic and editorial decisions would be a great starting place for improving the experiences and livelihoods of Australian musicians using music streaming services, as well as a compelling avenue for future research in this field.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sophie Freeman

Sophie Freeman is a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne, researching music streaming services and the user experience of algorithmic recommendation and curation. She is a member of the Human-Computer Interaction group, and works across the School of Computing & Information Systems, and the School of Culture & Communication.

Martin Gibbs

Martin Gibbs is a Professor of Human-Computer Interaction in the School of Computing and Information Systems at the University of Melbourne. His research interests lie at the intersection of Science Technology Studies (STS) and Human Computer Interaction (HCI). Recent projects have examined domestic media ecologies, digital commemoration, and vernacular creativity.

Bjørn Nansen

Bjørn Nansen works in the media studies program at the University of Melbourne. His research explores digital media and communication technologies in family life, and covers areas including children’s digital technology use, digital parenting, household technology innovation and adoption, death and digital memorialization, and family data tracking technologies.

Notes

1. We have included the song streams as an illustrative point, as many of our discussions with participants concerned gaining more streams or the value of a stream. However, we did not include the number of streams as signifier of the success of these artists. Indeed, many of them had achieved considerable success, in their own terms, outside of music streaming platforms.

2. Triple J is Australia’s national youth radio broadcaster. It’s a subsidiary of the Australian Broadcasting Company (ABC) and it is publicly funded.

3. User-centric models involve more direct payments between listeners and artists. In these models, artists receive revenue from the listeners that have actually streamed their music. rather than revenue being split from the total streamshare.

Works Cited

- Arditi, David. “Digital Subscriptions: The Unending Consumption of Music in the Digital Era.” Popular Music and Society, vol. 41, no. 3, May 2018, pp. 302–18. doi:10.1080/03007766.2016.1264101.

- Barna, Emília. “Between Cultural Policies, Industry Structures, and the Household: A Feminist Perspective on Digitalization and Musical Careers in Hungary.” Popular Music and Society, vol. 45, no. 1, 2022, pp. 67–83. doi:10.1080/03007766.2021.1984022.

- Bartlett, Matt, Fabio Morreale, and Gauri Prabhakar. “Analysing Privacy Policies and Terms of Use to Understand Algorithmic Recommendations: The Case Studies of Tinder and Spotify.” Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, vol. 53, no. 1, Apr. 2022, pp. 119–32. doi:10.1080/03036758.2022.2064517.

- Barton, Keith C. “Elicitation Techniques: Getting People to Talk About Ideas They Don’t Usually Talk About.” Theory & Research in Social Education, vol. 43, no. 2, Apr. 2015, pp. 179–205. doi:10.1080/00933104.2015.1034392.

- Baym, Nancy K. “Playing to the Crowd: Musicians, Audiences, and the Intimate Work of Connection.” Playing to the Crowd, New York UP, 2018.

- “Behind the Playlists: Your Questions Answered by Our Playlist Editors.” Spotify for Artists, 24 Feb. 2020, https://artists.spotify.com/blog/behind-the-playlists-your-questions-answered-by-our-playlist-editors. Accessed 16 Mar. 2023.

- Bishop, Sophie. “Managing Visibility on YouTube Through Algorithmic Gossip.” New Media & Society, vol. 21, no. 11–12, Nov. 2019, pp. 2589–606. doi:10.1177/1461444819854731.

- Bonini, Tiziano, and Alessandro Gandini. “‘First Week is Editorial, Second Week is Algorithmic’: Platform Gatekeepers and the Platformization of Music Curation.” Social Media + Society, vol. 5, no. 4, Nov. 2019, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2056305119880006.

- Bonini, Tiziano, and Alessandro Gandini. “The Field as a Black Box: Ethnographic Research in the Age of Platforms.” Social Media + Society, vol. 6, no. 4, Oct. 2020, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2056305120984477.

- Brusila, Johannes, Martin Cloonan, and Kim Ramstedt. “Music, Digitalization, and Democracy.” Popular Music and Society, vol. 45, no. 1, Jan. 2022, pp. 1–12. doi:10.1080/03007766.2021.1984018.

- Bucher, Taina. “Want to Be on the Top? Algorithmic Power and the Threat of Invisibility on Facebook.” New Media & Society, vol. 14, no. 7, Nov. 2012, pp. 1164–80. doi:10.1177/1461444812440159.

- Carlsson, Sven, and Jonas Leijonhufvud. Spotify Untold. Diversion Books, 2021.

- Colbjørnsen, Terje. “The Streaming Network: Conceptualizing Distribution Economy, Technology, and Power in Streaming Media Services.” Convergence, vol. 27, no. 5, Oct. 2021, pp. 1264–87. doi:10.1177/1354856520966911.

- Cotter, Kelley. “Playing the Visibility Game: How Digital Influencers and Algorithms Negotiate Influence on Instagram.” New Media & Society, vol. 21, no. 4, Apr. 2019, pp. 895–913. doi:10.1177/1461444818815684.

- deWaard, Andrew, Brian Fauteux, and Brianne Selman. “Independent Canadian Music in the Streaming Age: The Sound from Above (Critical Political Economy) and Below (Ethnography of Musicians).” Popular Music and Society, vol. 45, no. 3, 2022, pp. 251–78. doi:10.1080/03007766.2021.2010028.

- Drott, Eric A. “Music as a Technology of Surveillance.” Journal of the Society for American Music, vol. 12, no. 3, 2018, pp. 233–67. doi:10.1017/S1752196318000196.

- Eriksson, Maria. “The Editorial Playlist as Container Technology: On Spotify and the Logistical Role of Digital Music Packages.” Journal of Cultural Economy, vol. 13, no. 4, July 2020, pp. 415–27. doi:10.1080/17530350.2019.1708780.

- Eriksson, Maria, et al. Spotify Teardown: Inside the Black Box of Streaming Music. MIT Press, 2019.

- Ferraro, Andres, et al. “What is Fair? Exploring the Artists’ Perspective on the Fairness of Music Streaming Platforms.” IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. Springer International Publishing, 2021.

- Fleischer, Rasmus. “Towards a Postdigital Sensibility: How to Get Moved by Too Much Music.” Culture Unbound: Journal of Current Cultural Research, vol. 7, no. 2, June 2015, pp. 255–69. doi:10.3384/cu.2000.1525.1572255.

- Freeman, Sophie, Martin Gibbs, and Bjørn Nansen. “‘Don’t Mess with My Algorithm’: Exploring the Relationship Between Listeners and Automated Curation and Recommendation on Music Streaming Services.” First Monday, Jan. 2022. doi:10.5210/fm.v27i1.11783.

- Gillespie, Tarleton. “The Politics of ‘Platforms.’” New Media & Society, vol. 12, no. 3, May 2010, pp. 347–64. doi:10.1177/1461444809342738.

- Gitelman, Lisa, and Virginia Jackson. “Introduction.” Raw Data is an Oxymoron, MIT Press, 2013, pp. 1–14.

- Hagen, Anja Nylund. “Datafication, Literacy, and Democratization in the Music Industry.” Popular Music and Society, vol. 45, no. 2, 2021, pp. 184–201. doi:10.1080/03007766.2021.1989558.

- Hagen, Anja Nylund. “The Playlist Experience: Personal Playlists in Music Streaming Services.” Popular Music and Society, vol. 38, no. 5, Oct. 2015, pp. 625–45. doi:10.1080/03007766.2015.1021174.

- Hesmondhalgh, David. “Streaming’s Effects on Music Culture: Old Anxieties and New Simplifications.” Cultural Sociology, vol. 16, no. 1, Mar. 2022, pp. 3–24. doi:10.1177/17499755211019974.

- Hracs, Brian J., and Jack Webster. “From Selling Songs to Engineering Experiences: Exploring the Competitive Strategies of Music Streaming Platforms.” Journal of Cultural Economy, vol. 14, no. 2, Mar. 2021, pp. 240–57. doi:10.1080/17530350.2020.1819374.

- “Industry Data.” IFPI, https://www.ifpi.org/our-industry/industry-data/. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

- Kiberg, Håvard, and Hendrik Spilker. “One More Turn After the Algorithmic Turn? Spotify’s Colonization of the Online Audio Space.” Popular Music and Society, vol. 46, no. 2, 2023, pp. 151–71. doi:10.1080/03007766.2023.2184160.

- Kjus, Yngvar. “License to Stream? A Study of How Rights-Holders Have Responded to Music Streaming Services in Norway.” International Journal of Cultural Policy, vol. 28, no. 1, Apr. 2021, pp. 1–13. doi:10.1080/10286632.2021.1908276.

- Maasø, Arnt, and Anja Nylund Hagen. “Metrics and Decision-Making in Music Streaming.” Popular Communication, vol. 18, no. 1, Jan. 2020, pp. 18–31. doi:10.1080/15405702.2019.1701675.

- Maasø, Arnt, and Hendrik Storstein Spilker. “The Streaming Paradox: Untangling the Hybrid Gatekeeping Mechanisms of Music Streaming.” Popular Music and Society, vol. 45, no. 3, 2022, pp. 300–16. doi:10.1080/03007766.2022.2026923.

- “Made to Be Found.” Spotify for Artists, https://found.byspotify.com. Accessed 16 Mar. 2023.

- Meier, Leslie M., and Vincent R. Manzerolle. “Rising Tides? Data Capture, Platform Accumulation, and New Monopolies in the Digital Music Economy.” New Media & Society, vol. 21, no. 3, 2019, pp. 543–61. doi:10.1177/1461444818800998.

- Morgan, Benjamin A. “Optimisation of Musical Distribution in Streaming Services: Third-Party Playlist Promotion and Algorithmic Logics of Distribution.” Rethinking the Music Business: Music Contexts, Rights, Data, and COVID-19, edited by Guy Morrow, et al., Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 151–69.

- Morgan, Benjamin A. “Revenue, Access, and Engagement via the In-House Curated Spotify Playlist in Australia.” Popular Communication, vol. 18, no. 1, Jan. 2020, pp. 32–47. doi:10.1080/15405702.2019.1649678.

- Morris, Jeremy Wade. “Curation by Code: Infomediaries and the Data Mining of Taste.” European Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 18, no. 4–5, 2015, pp. 446–63. doi:10.1177/1367549415577387.

- Morris, Jeremy Wade. “Music Platforms and the Optimization of Culture.” Social Media + Society, vol. 6, no. 3, July 2020, pp. 2056305120940690. doi:10.1177/2056305120940690.

- Morris, Jeremy Wade, and Devon Powers. “Control, Curation and Musical Experience in Streaming Music Services.” Creative Industries Journal, vol. 8, no. 2, 2015, pp. 106–22. doi:10.1080/17510694.2015.1090222.

- “NerdOut@Spotify.” Spotify, https://open.spotify.com/episode/6dVA0HyWHdHDW8t3mSOBQd?si=2642223db87c42dc. Accessed 21 Feb. 2023.

- Nickell, Chris. “Promises and Pitfalls: The Two-Faced Nature of Streaming and Social Media Platforms for Beirut-Based Independent Musicians.” Popular Communication, vol. 18, no. 2, 2019, pp. 48–64. doi:10.1080/15405702.2019.1637523.

- Nieborg, David B., and Thomas Poell. “The Platformization of Cultural Production: Theorizing the Contingent Cultural Commodity.” New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 11, Nov. 2018, pp. 4275–92. doi:10.1177/1461444818769694.

- Nowak, Raphaël, and Benjamin A. Morgan. “New Model, Same Old Stories?” Music and Democracy: Participatory Approaches, 2021, pp. 61–83.

- O’Dair, Marcus, and Andrew Fry. “Beyond the Black Box in Music Streaming: The Impact of Recommendation Systems Upon Artists.” Popular Communication, vol. 18, no. 1, Jan. 2020, pp. 65–77. doi:10.1080/15405702.2019.1627548.

- Pelly, Liz. “Streambait Pop.” The Baffler, 11 Dec. 2018, https://thebaffler.com/downstream/streambait-pop-pelly.

- “Playlisting – S4A.” Spotify for Artists, https://artists.spotify.com/playlisting. Accessed 16 Mar. 2023.

- Prey, Robert. “Knowing Me, Knowing You: Datafication on Music Streaming Platforms.” Big Data und Musik: Jahrbuch für Musikwirtschafts- und Musikkulturforschung, edited by Michael Ahlers, et al., 2019, pp. 9–21.

- Prey, Robert. “Locating Power in Platformization: Music Streaming Playlists and Curatorial Power.” Social Media + Society, vol. 6, no. 2, Apr. 2020, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2056305120933291.

- Prey, Robert, Marc Esteve Del Valle, and Leslie Zwerwer. “Platform Pop: Disentangling Spotify’s Intermediary Role in the Music Industry.” Information, Communication & Society, vol. 25, no. 1, May 2020, pp. 1–19. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2020.1761859.

- Robards, Brady, and Siân Lincoln. “Uncovering Longitudinal Life Narratives: Scrolling Back on Facebook.” Qualitative Research, vol. 17, no. 6, Dec. 2017, pp. 715–30. doi:10.1177/1468794117700707.

- Seaver, Nick. “Algorithms as Culture: Some Tactics for the Ethnography of Algorithmic Systems.” Big Data & Society, vol. 4, no. 2, 2017, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2053951717738104.

- “Spotify: A Product Story with Gustav Söderström.” Spotify, https://open.spotify.com/show/3L9tzrt0CthF6hNkxYIeSB. Accessed 21 Feb. 2023.

- Tofalvy, Tamas, and Júlia Koltai. “‘Splendid Isolation’: The Reproduction of Music Industry Inequalities in Spotify’s Recommendation System.” New Media & Society, July 2021, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/14614448211022161.

- Towse, Ruth. “Dealing with Digital: The Economic Organisation of Streamed Music.” Media, Culture & Society, vol. 42, no. 7–8, Oct. 2020, pp. 1461–78. doi:10.1177/0163443720919376.

- Vonderau, Patrick. “The Spotify Effect: Digital Distribution and Financial Growth.” Television & New Media, vol. 20, no. 1, Jan. 2019, pp. 3–19. doi:10.1177/1527476417741200.

- Webster, Jack, et al. “Towards a Theoretical Approach for Analysing Music Recommender Systems as Sociotechnical Cultural Intermediaries.” Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Web Science, Association for Computing Machinery, 2016, pp. 137–45.

- Wikström, Patrik. The Music Industry: Music in the Cloud. John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

- Zhang, Qian, and Keith Negus. “Stages, Platforms, Streams: The Economies and Industries of Live Music After Digitalization.” Popular Music and Society, vol. 44, no. 5, Oct. 2021, pp. 539–57. doi:10.1080/03007766.2021.1921909.