ABSTRACT

This article sets out to counter dominant depictions of DJs and clubbing that privilege white male DJs and their scenes, and that erase nightclubbing’s Black queer origins. Using queer oral history interviews and engaging with material fragments from the time (playlist notes, flyers, records), I focus on London in the late 20th century, where Black and white lesbian DJs, promoters, and clubbers created their own club scene. The scene’s events and nights were a combination of queer women’s creative cultural activism and the love of music that DJs and dancers shared, away from the surveillance and gaze of the straight world.

Introduction

This article draws attention to the Black and white lesbians who organized and promoted music nights for women that were accessible, safe, affordable, and in spaces that disrupted the heteronormative map of London in the 1980s and 1990s. Missing from most accounts of clubbing and music scenes are the creative accomplishments of women. Texts, then and now, within academia and popular music publications, document clubbing but privilege white, and white male scenes, their perspectives, and their protagonists.Footnote1 I present here accounts of the female vinyl junkies who scoured record shops and collected albums, 12-inch singles, and 45s to play and share at women’s and lesbian events; women who set up their own sound systems, rapped, sang, chatted on the mic, and DJed; and the women who went out seeking great tunes to listen to and dance to. Women applied their in-depth musical knowledge and their cultural activism into creating and nourishing the spaces where women who loved women could be with others, and could find sanctuary away from the surveillance, restrictions, and aggressions of the straight world. Lesbian promoters, DJs, and clubbers connected on the dancefloors, transforming these spaces into sites of queer jouissance, sharing the low-end frequencies where queer women could groove together, their bodily movements and the sonic merging and dissolving.

Women bought, collected, and listened to records, sharing music, and creating their own cultural scene. This creative activism gave them a collective sense of their place in the world. Simon Frith notes that social groups can make and form their sense of identity through sharing music: “music gives us a way of being in the world, a way of making sense of it” (114). At a time when being out as lesbian, gay, or bisexual could result in homophobia, as well as negative and/or violent consequences, these club nights helped women to figure out their identities and build communities through being with and dancing with other women, the music acting as a conduit to socialize, find intimacy, and affirm their sexuality. Many women at the time had to keep their sexuality secret, hidden from other aspects of their lives, and they could only find expression and a home for this essential part of themselves on the women’s music scenes.Footnote2

This is not a comprehensive, complete, or definitive account of the lesbian scene in London during this period. The scene continually developed and changed with nights catering for the many and varied tastes and preferences of the women that made up the broader lesbian community. Different nights addressed the needs, for example, of fans of indie music and also the women whose priority was to go out and listen to mainstream tunes. The article zooms in on a particular music scene, within the wider lesbian club scene, where music of the Black Atlantic was played. This provides the context, too, of the influence of Black British sound systems on the club scenes in the UK at that time: I consider the significance of Black music, its creation explicitly linked to white racist capitalist oppression, and the music’s messages of hope and redemption. I am writing this as an insider on this scene. As a white lesbian DJ, I have benefitted from Black music, culturally, politically, materially, and educationally. Listening to artists such as Stevie Wonder, Esther Phillips, and Gil Scott-Heron in my teens, I was opened to a socio-political education that was absent from my mainstream schooling. In “Black Man,” Wonder lists how the white supremacist’s history of America omits the Black, Brown, and indigenous people that contributed to the formation of the nation; Phillips sang of drug abuse and domestic violence in “Home Is Where the Hatred Is”; and Scott-Heron protested against apartheid in “Johannesburg.” For me, these were all inspirational insights into politics and culture that I could not find anywhere else. Music was the conduit for this new education and my reading of the world. I collected records, found out all I could about the singers, groups, and musicians from liner notes and magazines, seeking out new and old tunes for my collection. In my twenties I was a regular clubber and DJ, dancing and spinning vinyl on the women’s and straight club scenes in London.

I collected flyers from the nights where I DJed and the club nights and music events that I attended. Not realizing the significance of these everyday mundane items at the time, my collecting for some future scrap book of memorabilia in effect affirmed my identity and cultural life. These ephemeral items are now invaluable documentation of scenes and the ways women communicated, created, and found communities that would otherwise be lost.

Recovering Club Night Memories

I use archival activism to access the memories and document these fleeting moments in late 20th century, lesbian London, and to bring this history to life. Using methods that disrupt traditional notions of the archive—memorabilia from the time, flyers, mix tapes, and musical tracks in conversation with queer oral history interviews—I hope to bring the events, the women, the places, to the foreground and salvage this scene from being forgotten and ignored. I shared materials that I’ve kept and collected with six oral history narrators from the period (Anabel, Brigitte, Carole, Denise, Monica, and Esther) to trigger discussions of our memories. Using the flyers and objects as what John Willsteed refers to as an “activator of subcultural stories” (168), we discussed the recollections that were triggered. We talked about nights out on the scene, remembering the times, the tracks played at various gigs, the atmosphere of a night out, and how we would travel around London, seeing familiar faces and how the nightlife fitted in with the lives we lived.Footnote3

The objects … have an intrinsic aesthetic value as well as being representative of the time, energy and social connection required to devise and produce them … with a different curatorial focus they can be moved to the centre of the story as representative of this social and cultural activity. (Willsteed 168)

To add to the study, I also carried out shorter focused interviews with two more women, Lorna and Paulette, who spoke about their memories and experiences of the women’s scenes. Their accounts complement the recollections gathered from the other six narrators to add to this developing archive. Putting ourselves, Black and white queer women, at the center of our story in the collaborative act of remembering these times evokes and stimulates discussion. In carrying out these interviews we jointly activated recollections and thoughts from our pasts, recouping an overdue history. In this way we accessed the queer embodied archive. This archive is held in our bodies and is shaped by our emotions, our experiences as lesbian, bisexual, gay, queer, and the particular histories that we have lived through.

Queer oral historians working with queer narrators intentionally upset and disrupt the power relations between the traditional historian’s dispassionate, objective methods of researching their subjects, and in so doing work collaboratively with their co-narrators whose position in the telling/re-telling is active and involved. This methodology engages with elements that in combination form three elements of the “nexus” that Noah Riseman refers to: oral history, formal archival documents, and personal archives. This a powerful method as the queer oral historian works in tandem with their narrator/s to find “evidence of me” and, ultimately, evidence of “us” (Riseman 61).Footnote4

Terry Cook presented four key archival paradigm shifts over the last 200 years. He listed evidence, memory, identity, and community to indicate the fluidity and changing definition of archival work, the role and place of the archivist, and the archive itself. Adding to Cook’s four phases, recent explorations have further extended what we may consider to be archives: the queer body as archive, queer oral history’s disruptive archives, ephemeral Black music archives, the archive of feelings Ann Cvetkovich describes that lesbians carry in their bodies and express in their creativity, and Saidiya Hartman’s use of archive and historic narrative in her historic fabulation Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments:

Every historian of the multitude, the dispossessed, the subaltern and the enslaved is forced to grapple with the power and authority of the archive and the limits it sets on what can be known, whose perspective matters, and who is endowed with the gravity and authority of the historical actor. (xiii)

These paradigm shifts continue to move the practice, the meaning, and the ownership of the archive forwards in a democratizing way, incorporating oral history, memories of major events where documentation has been destroyed, and into the identity of marginalized under-represented groups and communities.

Old memorabilia, the flyers and posters in personal collections and marginal archives, are perhaps the only tangible evidence of the underground events which can give us a record of the contribution of women’s cultural expertise and work. Throughout the ’80s and early ’90s, women wishing to put on an event in a straight venue faced many barriers. It was difficult to persuade bars or pubs to host a women’s event: women’s spending power was less than men’s, women didn’t drink as much alcohol as men, and anti-lesbian, racist, homophobic, and misogynistic attitudes from bar managers, bar and door staff was common. Black and white women and lesbians prioritized their safety and security when planning to go out to meet other women. The possibility of booking a lesbian-friendly venue for a Friday or Saturday night in a central, accessible location, was very limited. The London lesbian club nights that emerged during the 1980s and 1990s were DIY DIT (Do It Together) endeavors, running underneath, alongside, and against the confines of the straight club scene’s spaces. Because of the threats of violence and harassment toward lesbians, the promotion and advertising of these events was done by word of mouth, flyers left on noticeboards in women’s centers and bookshops, and distributed at venues and, occasionally, briefly covered in the city’s listings magazines. Filming or photography at events happened very rarely due to the potential consequences of being outed as gay, lesbian, or different from the heterosexual norm, and the potentially damaging consequences for a woman’s housing, employment, and family situation. Therefore, very little visual documented evidence exists. This influence and knowledge are erased from many accounts of the history of clubbing and sound system culture. In his otherwise excellent account of London’s Black music scenes, Caspar Melville states that there were no women’s sound systems: “sounds, all run by men, took on the form of the patriarchal family” (60). He does acknowledge “exceptions,” noting that “with few exceptions the promoters and DJs were all men” (88). Women are peripheral in Lloyd Bradley’s books on reggae and Black British music,Footnote5 and the promise of Gilbert and Pearson’s Dance Music, Culture and the Politics of Sound gives little acknowledgment of women’s experience, creative work, and input to clubbing.

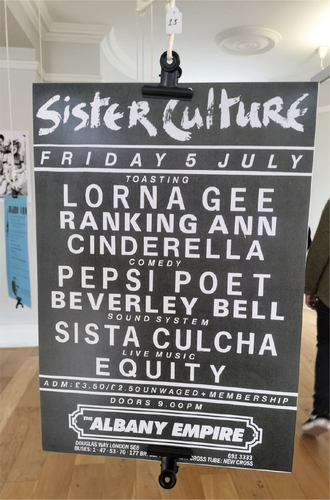

The cultural significance of women’s work and their contributions to various music scenes has only recently been acknowledged. , a poster from the 2023 Black Ink Collective exhibition at the Black Cultural Archives, advertises an event at the Albany Empire, London, in the early 1980s, and showcases “Sister Culture,” an evening of Black women’s music and words.

Figure 1. Poster from Black Ink Collective, early 1980s. Writer’s photograph from the exhibition, When Trouble Come, Ink Haffi Run Exhibition, at Black Cultural Archives, Brixton, June 7, 2023.

In Dance Your Way Home, Emma Warren lists women who were involved and ran some of London’s sound systems: “There were many women involved, including individuals like Sista Culcha, Bionic Rhona, Olive Ranks, Ranking Ann and Sister Candy, along with sounds like Ladies Choice, Silhouette and Nzinga Soundz” (87). Lynda Rosenior-Patten and June Reid chronicle the many women DJs, singers, and sound systems: “Of course, a number of Black women have contributed to DJing, sound systems and broadcasting in the UK. With a few exceptions, the majority remain unknown, despite, in some instances, being active for over 30 years” (126). We could add to this other women and lesbians who were active on the women’s scene: Nikki Lucas DJed and ran various club nights across London; DJ Ritu, now a successful radio DJ, started out playing music on the women’s and gay scenes at Club Kali and Asia nights; DJ and promoter Yvonne Taylor and DJ Rocksteady Eddy set up the women’s sound system Sistermatic and put on women’s nights at the South London Women’s Centre, Acre Lane in Brixton.

Our Own Spaces

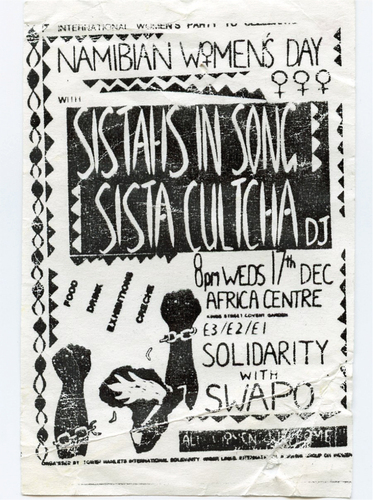

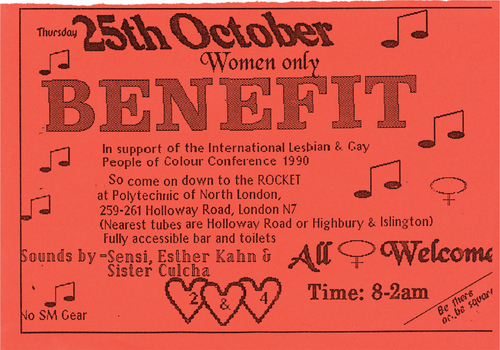

This article starts in the 1980s when many of the events for lesbians were women only “benefits,” events where political causes were highlighted, and the proceeds were used to support various campaigns and political groups (see ). These benefits raised funds and awareness in support of local, national, and international struggles and campaigns. The 1980s was a period of political change, activism, and vibrant resistance to Maggie Thatcher’s ruling Tory regime. This included opposition to Clause 28, protests against the Poll Tax, support for the Troops Out campaign, campaigning for the striking miners, and solidarity with freedom fighters in South Africa and South America. These events were usually held in publicly owned venues, for example Camden Town Hall in Judd Street, and student union spaces such as the Rocket in Holloway Road (premises that were run by the North London Polytechnic Student Union). South London Women’s Centre in Brixton held regular Saturday club nights and the Factory Community Centre in Matthias Road, Stoke Newington, held one-off women only parties. Here the costs of hiring were low, and the organizers of the events were welcomed by the host venues. The opening of the Greater London Council-funded London Lesbian and Gay Centre in 1985 presented women with an accessible space in central London to organize music and arts events for other women.

A vibrant period of change was also taking place on London’s wider straight club scene, in parallel to the changes that were taking place on the lesbian and gay scenes, as the late 1980s merged into the early 1990s. In the 1980s, London’s spaces were pre-gentrification: vast swathes of the cityscape were derelict, with huge boarded up empty buildings ripe to be taken over by squatted music nights which became successful sonic weekend escapes. Warehouse parties and Acid House raves drew dancers together across gender and racial lines and these takeovers of deserted properties were a determined anti-racist riposte to the practice of quotas based on race that many central London clubs exercised on their doors. DJs and promoters took over abandoned warehouses, installed sound systems, and put on their own club nights. The influence of Black British sound system culture was at play here and on the women’s scenes with groups marginalized by their race and gender taking over buildings to provide much needed spaces of culture. Mirroring the straight scene, women took opportunities to use available spaces and premises to cater for their sonic needs. Women put on house parties and blues nights in squats and women’s centers, hiring equipment or bringing their own sound systems.

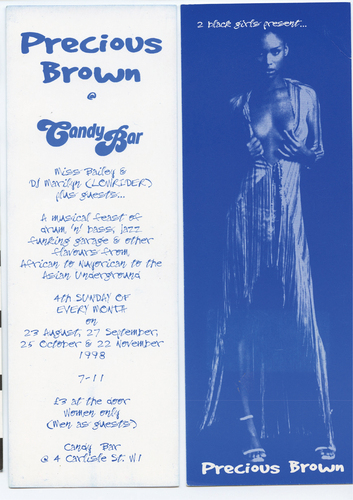

Toward the late 1980s, tolerance and relative acceptance of lesbians and gays became more mainstream, and, from the mid-1990s, there was an increase in commercialized opportunities from both straight-owned venues and gay and lesbian owned pubs and bars. This led to more locations becoming available for women to hire for their nights. As the decade progressed, straight venues became more open to hosting lesbian and gay events and several women-owned bars opened that catered to lesbian and gay customers. These included Elaine McKenzie’s Glass Bar, a women only private members club outside Euston station (1991–1998)Footnote6; the Duke of Wellington and The Royal Oak in Hackney; Due South in Stoke Newington; and Blush in Cazenove Road, also in Stoke Newington. Kim Lucas, a club promoter, opened the Candy Bar in 1996 in Soho where men were admitted as guests if they attended with the bar’s women customers. Yvonne Taylor continued promoting her clubs, including the Sunday Happy Day events at the Soho Theatre Bar in central London, into the early 2000s. The DJ and promotor Ain Bailey, now a successful sound artist, had a regular night DJing with DJ Marilyn at the Precious Brown night at the Candy Bar in Soho (see ) from 1996 for around three years. These and many other women are unacknowledged in clubbing’s histories. However, as women’s spending power remained lower than gay men’s, any weekend night was hard to procure. Women were still marginalized, and nights that Black women could safely travel to, where they could party safely, were even more difficult to find and maintain. Women’s nights were, therefore, precarious, and too often short-lived. A good night out was hard to find and the joy it could provide was a very special element of our cultural lives and worlds. Women would look forward to the excitement, the mystery of who would be there, and anticipate the music, the fashion, and the connections that could be made on this marginal scene. By sharing the ephemera, looking at the objects and discussing them, a fuller picture of the lesbian music scene begins to emerge. Stories and recollections are shared, and the essence and histories of this time can begin to be rescued. The transient things accumulated from over thirty years ago tell stories and begin to present an account of our history. The value here is in salvaging something from our pasts that can be added to the writings on London’s club cultures and, unusually, posit the work and culture of Black and white lesbians from the margins they too often inhabit to a centered place.

The oral history participants viewed several flyers, including the Namibian Women’s Day benefit night flyer from the mid 1980s (see ). This is an example of a hand-drawn flyer, pre-dating desktop publishing. All the graphics and text are manually illustrated and then copied using cheap white photocopier paper and black and white technology. Dating back to the 1980s, it is quite worn, but the words “all women welcome” remain visible in the bottom right corner. Alongside the intentions and entertainment available at this event, women would understand the coded message of these three words. Rather than using “women only,” “all women welcome” reached out to women who loved women and preferred to spend an evening in a women’s environment. We discussed this strategy in the oral history interviews and the many times that men, hearing the music, would approach the door staff and attempt to gain access. They would be told that the event was a private party. This was a less antagonistic way of deterring men’s attention and possible aggression if they knew it was a lesbian event. Men’s access to public and private spaces is rarely questioned and encompasses many gendered territories where women may not feel at ease or welcome. It was thus important to establish women’s spaces and develop door policies that maintained this in safe ways.

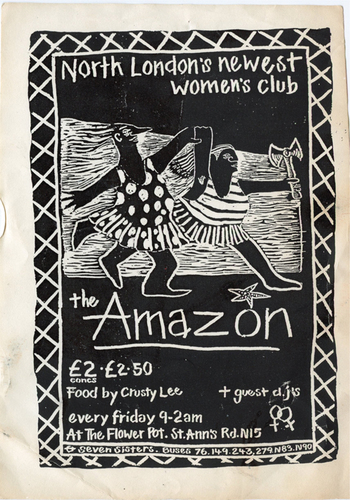

The emphasis on solidarity with the Namibian Women’s Day and the cultural and political importance of linking together against oppression demonstrates the political context of the ’80s. Here, common causes across post-colonial struggles and freedom fighting were supported through cultural activities. On this flyer and others, the entry price to the gig is on a sliding scale according to financial status. This was an important tenet of many club organizers and is also imprinted on the Amazon night flyer (see ), which advertises “North London’s newest women’s club.” Coded messages in this flyer suggest whom the organizers were hoping to target. During the oral history interviews, Monica recalled that nights set up by Black women would not necessarily use the word lesbian in the flyers. “Lesbian” was viewed as terminology used by white, middle-class lesbian feminists. However, there are clues for those in the know. The woman on the right is holding a labrys, or double ax, in her left hand. This is a Greek symbol that women who loved women would wear as jewelry that signified sexual preference for women. We could also see the double Venus symbol, also used as a signifier in the lesbian community, in the bottom right corner of this flyer. These codes were important for women to recognize the messages just below the surface that indicated what the night would be like. There was no social media where recommendations and reviews could be found so the designers added these clues for their potential audience to discern.

Brigitte was one of the organizers of the Lesbian and Gay People of Color Conference and her memories of her activism at the time was triggered by seeing a benefit flyer for the first time in thirty years (see ). She had suggested an additional workshop at the event for “mixed race” people of color to have some space to discuss their particular situations and identities. Not certain anyone would turn up, the organizers were surprised when the session was attended by thirty people. The session led to the formation of a significant group named Mosaic that would continue for several years, meeting, organizing cultural, political, and social events, and convening annual conferences throughout the UK for members. Friendships were formed around their intersectional identities and have lasted until the present day. Anabel also attended the benefit, remembered the DJs and the other venues that they had played. She recalled that the DJs Sista Culcha and Sensi both played at the South London Women’s Centre regular women’s club nights.

The flyer signals that one of the organizers had access to basic word processing technology and mixed various bit mapped graphic elements across the composition to convey messages to potential attendees. The design has then been photocopied on A4 paper and folded and torn to maximize the number of sheets that could be produced. Key information around transport links and the address of the venue are provided, along with a note that there was a “fully accessible bar and toilets.” The DJs Sensi, Sister Culcha, and Esther Khan were well known on the scene and would attract their own crowd of followers to listen and dance to their music. We assumed the inside the hearts communicate the sliding scale of entry price according to status as unemployed/low waged or employed. In the bottom left corner, there is a warning, “No SM gear,” indicating that those women who wore SM (Sado Masochist) regalia would not be welcome. Women wearing leathers and Nazi regalia would have been turned away from this event due to the offense caused to many. The women on either side of these arguments often confronted each other in the same social spaces and the policing of dress codes was passionately debated between various groups and communities that made up the broader lesbian community. (For more on this, the film Rebel Dykes presents a brief history from women who attended SM nights.) SM lesbians did have their own nights and events, including Chain Reaction in Vauxhall. As there was a dearth of events across the wider lesbian scene, at many nights there would be a mix of lesbians and women who would broadly fit into different groupings, including lesbian feminists, political lesbians, lesbians who just wanted to go out and party, women into the DJ or music being played, and women who were perhaps visiting London for the first time.

In the oral history interviews, Brigitte described how everyone’s skills and access to technology would be utilized in order to find cheap, quick, and effective ways to produce and distribute their flyers. She was often asked to do the illustrations even though she thought that she couldn’t draw. We also observed that DJ Sista Culcha’s name has two different spellings across these flyers, reflecting the DIY and amateur approach of the time and the immediacy of communicating key information. Where today’s technology would automatically correct spellings, and the costs of running club nights may limit access to many on low wages, this scene’s values were contingent on prioritizing collective values to provide accessible and affordable access to club spaces.

We recalled too that the space and music of the lesbian dancefloor became our space, space for our bodies to release the tensions of the straight world. We repurposed the walls and sonic spaces for ourselves, no longer confined by the limitations of straight society. Gill Valentine outlines how every physical environment is a challenge to lesbians and queers in that these are constructed and designed to accommodate the white, straight, heteronormative world. It is so pervasive that we may not even notice its impact on us, our bodies, and our emotional selves, and as we will unconsciously struggle to feel comfortable, we will shrink and be confined and constricted.

[H]eterosexuality is clearly the dominant sexuality in most everyday environments, not just private spaces, with all interactions taking place between sexed actors. However, such is the strength of the assumption of the “naturalness” of heterosexual hegemony, that most people are oblivious to the way it operates as a process of power relations in all spaces. (Valentine 396)

When Black and white women collaborated to create these alternative sites of pleasure, there was a liberating, transformational impact of the space and the music on our bodies, on us. On the women’s dancefloor, the space, the sounds, and the bodies could connect and experience an emancipating alternative to heteropatriarchal settings. The environment of the club was transformed through women working together, the music drawing women to the spaces. Rather than feeling out of place and experiencing the world as aggressions and discomforts, sanctuary could be found on the dancefloor, moving our bodies with other women, known and unknown, strangers, lovers, encounters hoped for and met. Going out on the women’s scene, lesbians could find release through moving to, through, and within the music. “The music helps return the listener to the pleasures of sensory embodiment that trauma destroys” (Cvetkovich 1). Here lesbians could shake off the constraints of the straight world, find a home, rebound from the internalized constrictions of straight male-dominated behavioral expectations of women and find parts of ourselves.

All space is racially territorialized. White normativity is imposed through state surveillance and racist policing, and enacted in daily racist aggravations that create hostile environments for Black people. I do not claim that the women’s scene was a utopia. Society’s issues did play out. In the oral history interviews, one club promoter reported how Black women were turned away from one venue by racist door staff, and the promoters then decided to end working with this venue and moved the night to another location. However, it is clear that there were efforts and actions taken by many on the women’s scene to adhere to generally agreed standards, a desire, for example, to provide social spaces, safe places where all women could be catered.

In her interview about being out on the women’s scene and her experiences negotiating space as a Black woman, Paulette spoke of the release she could find on the dancefloor:

For me the whole thing about Black people having the space to dance is that, for most of us, it was the one time that we were able to really express ourselves … when I got on that dancefloor I could just be, I could just be who I wanted to be, there were no … there is no preconceived ideas about me, there is no assumptions. It was just, you know, I’m here and I just wanted to dance. And I don’t want to be judged and I wasn’t judged, and that was the thing I liked about it because we were and still are incredibly judged in so many different ways in our lives.

When women move through public spaces there is omnipresent surveillance: we have a sense of being judged, watched, and at times threatened by elements of an environment that is not designed for our bodies and selves to negotiate our paths through. This inflicts daily, mundane pain, and necessitates a constant sense of vigilance. These can be explicit instances or disguised into the normal behavior and surroundings and are often expressed in day-to-day harassment and small quotidian traumas that Ann Cvetkovich describes. When women went out to straight and gay clubs the dancefloor would be dominated by men who purposed and took this space as their own. Melville describes this as placing “male forms of competition and display at the center to the exclusion of women” (89). By dancing in our own spaces, we were able to shrug off external somatic restraints, to begin to loosen our bodies in time to the movements of others on the dancefloor and within the sonic wall of the speakers, not using words but freeing up our bodies, immersed together through the basslines, melodies, and grooves.

For many women, the dancefloor is possibly the largest open space we experience in our lives, and this makes it a powerful, special space of possibilities. In Dance and Politics, Dana Mills tells of the power of dancing, moving one’s body, communicating without uttering words: “dance, like activism, holds unique power by providing its agents with extra verbal meaning” (Mills 3). The flow of lyrics and sentiments that the music conveyed would transmit to the dancers who would react to the moods and messages as individuals and as a collective group. Dancing was sharing, our gestures moving and expressing our lives from our interior world into the spaces where it was safe to be lost in the music. Our actions, gestures, and presence on the dancefloor let the music filter into our being at a subconscious, unspoken level. We could commune with ourselves and others across the sonic whole of the dancefloor. Women danced together, learning moves from each other through the process of entrainment and the signals prompted by the shifts and passages of the music.

In his study of Jamaican sound systems, Julian Henriques explains how sound’s wavebands are material, corporeal, and tangible, and traverse through our bodies as the dancers become the sonic body of the dancefloor, connected, and joined with each other (22). This is particularly emphasized by the sonic field that dub engineers create for reggae dancehall and dub events and has been adapted in the music systems installed in clubs and at music festivals. We became part of the music, part of the soundscape, and connected at the same time with the larger sonic body of the other dancers in those moments, connecting too with the memories of the dancefloors that went before, where we had danced, and others had moved their bodies. Dancing to a track like “Tears” (by Frankie Knuckles and Satoshi Tomie), we interact with the whole piece: the crescendos, diminuendos, dramatic turns, the mesmerizing bass and rhythm that transports us into trance-like states, our bodies become at one with the music, where often, too, our emotions are laid bare and rise to the surface. The volume and intensity of the bass in dance music enters our body, and we become part of a moment, and momentum joined to and within the dancing crowd, which develops into a wider body of belonging. We learn from each other, moving in response to the music and other dancers, improvising gestures that the rhythm of the crowd and the direction of the music stimulates in us, in time with the music, bringing us all together. The content of the lyrics, the phrases of the music, the progression of the track, transport us, move through our thoughts and emotions, bringing moments of transformation and remembrance: “bodies remember and carry narratives. They remember repression, but they also remember possibility for collective emancipation in movement and for empowerment in solidarity” (Mills 22).

Reworking Transport and Music

As we continued to decode the flyers, we noted the shift from public venues to commercial spaces and the continued importance of providing transport information (see ). The reliable twenty-four-hour public transport system that now exists in London is a far cry from the travel constraints that women faced in the ’80s and ’90s, when many relied on cars, lifts, and their own bikes to travel to and from parts of the city. Women were hyper-aware of their safety in traversing the city. Noting that public transport ended before midnight, the oral history narrators commented that cab drivers would refuse to travel from North London to South London. In response to this, and as a cheaper option, cycling was an effective way of going to and from venues; we recalled the large numbers of bikes that would be locked on the railings outside and near women’s club nights.

As women crisscrossed London in search of their club nights and events, resourcefulness and cooperation were key. Consisting of bike and car journeys, the new women’s taxi services like Lady Cabs in Hackney, and shout outs for lifts once the party was over, a map of these overlapping routes emerges. Beryl’s in Tottenham was unusual in its northern location and its hosting of a monthly Saturday night women’s event. It was a journey worth making but a challenge for those living south of the River Thames, who might struggle to return home. The oral history narrators recalled a memorable night when one woman clubber audaciously hijacked a London bus which was left idling in the bus garage opposite the club. She then drove it to south London, with a happy group of passengers in tow and grateful for a free ride home.

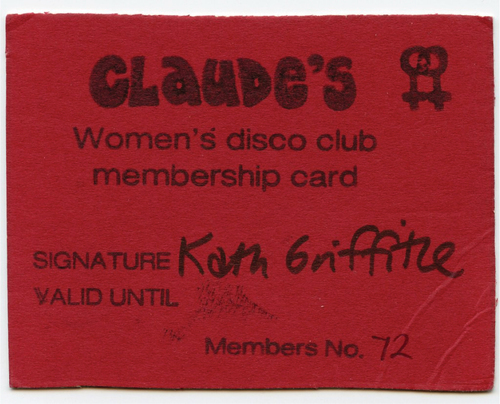

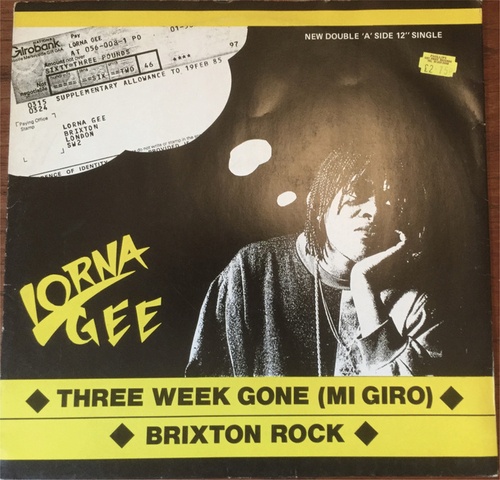

Combining memory, a membership card from Claude’s women’s disco club (see ), and an old 12-inch single from my collection (see ), the oral history narrators recalled a particularly memorable night. In the late 1980s, Lorna Gee played a PA (Public Address) of her ragga single “Three Week Gone (Mi Giro),” at Claude’s night in Dalston, a night where Black lesbians could party, hear great tunes, and be a sizable number of the clubbers. The song tells of a typical experience of “signing on” (i.e. claiming social security benefit) as an unemployed young woman and then waiting more than the expected two weeks for the check, or “giro,” to arrive, and the frustration of chasing this up at the Social Security office. Lorna Gee’s PA appearance at a lesbian night had its own risks but was a queer reclaiming and feminist rebuff of the dominant male and often sexist ragga lyrics of the time. She chats deftly on the mic, and with humor recounts her struggle, neatly mixing in references to the musical Fiddler on the Roof’s “If I Were a Rich Man” and Grandmaster Flash’s lyrics from “The Message” (“It’s like a jungle sometimes … ”).

The show, on a Tuesday night, was electric, with Black and white lesbians dancing and cheering her performance. Her intricate lyricism sits up there alongside Smiley Culture’s “Cockney Translator” as a fine example of Black British artists reflecting and critiquing everyday aspects of the life they faced. She recounts the experience of unemployment that would resound with many listeners, documenting the everyday hassle of late payments, intransigent civil servants, and a social security system designed to intimidate those who were entitled to benefits. Lorna and her musical contemporaries, Smiley Culture and Tippa Irie, were the Black British children of the Caribbean diaspora, asserting their belonging in Britain’s hostile environment. Lorna had schooled herself in the art of MCing: she often went to sound system events in South London where she would push herself to the front to chat on the mic. She spent time studying key figures and composing her own lyrics to popular riddims that the sound systems would play, like the Bobby Babylon riddim used in this disc. I interviewed Lorna about the song and her experiences of the women’s scene. In recounting its genesis and how she came about writing the track, she remembered her chance meeting with the dub poet and community activist, Linton Kwesi Johnson, under the “Welcome to Brixton” sign. It was the early 1980s, she had just visited the DHSS as her giro was late, and she had also just been offered a record deal with Ariwa records. She felt a bit stuck so she asked for LKJ’s advice on what she could write about. His advice was to write about her life, her experiences, reflecting how he has worked to document and reflect on Black British experience through his own poetry and writing:

[T]he popular music of Jamaica, the music of the people, is an essentially experiential music, not merely in the sense that the people experience the music, but also in the sense that the music is true to the historical experience of the people, that the music reflects the historical experience. (Johnson 5)

The music of the Black Atlantic is rooted in the appalling history of the West’s capitalist racist project: “Transatlantic slavery, that disaster of modernity and its ongoing effects” (Sharpe 272). The diasporic musics of Jamaica, the Caribbean, North and South America, and Black Britain carry the memories and messages, expressing the reality and impact of this history. While Lorna Gee does not describe herself as a political artist, the track expresses an activism that is cultural and political, elements that are intricately and intrinsically linked in the music of the Black Atlantic. Music made from the Black Atlantic diaspora critically reflects on this history and is an expression of these continuing circumstances. The music can offer a redemptive outlet for the listeners and dancers through its lyrics and sonic knowledge. Paul Gilroy notes that Black music both reflects on this past and imagines a better future. “This sub-culture … is in fact an elementary historical acquisition produced from the viscera of an alternative tradition of cultural and political expression which considers the world critically from the point of view of its emancipatory transformation” (137).

The political and cultural activism of London’s lesbians provided pleasure, musical wisdom, and convivial experiences. We moved to the dancefloor to feel this through our bodies and to share the release from our histories and traumas. Dancing and moving our bodies with strangers in the darkened, hot, sweaty, sexually charged spaces, we could find excitement, thrills, and harmony through dancing to the music. Seeking out joy on the dancefloor, we could be part of a queer world where we could melt and move, watch, and be watched, connect, and get lost in the music as the flow of the DJ’s set took the dancers on journeys, in the unique performative time and space of the club. Here, the space could be transformed, and the music could be reimagined into queer readings. The music played was not vastly different from the music on the straight club scenes. However, when played in a women’s space, the tunes and lyrics were reclaimed and re-interpreted, offering a liberating release from heteronormative demands. Classic tracks became anthems on the women’s scene and, at certain times and in certain places, there were guaranteed floor fillers. Aretha Franklin’s “Respect,” Jean Knight’s “Mr. Big Stuff,” and Vicki Anderson’s reply “I’m Too Tough for Mr Big Stuff” were interpreted with feminist readings. The songs “I’m Every Woman” by Chaka Khan and “We Are Family” by Sister Sledge were guaranteed to be greeted with a rush to the dancefloor as the recognizable openings urged the clubbers to move to and share their positive messages. Janet Kaye’s “Silly Games” would always combine a joyous rendition from the crowd when she hit the high falsetto at the chorus and the DJ dropped the volume. When the first bars of “Get Up (I Feel Like Being a) Sex Machine” by James Brown dropped, the script was flipped, and the male singer’s perspective was reclaimed as an expression of sexual agency and desire by women loving women.

Flirting, watching, and being watched was part of the play and ritual. Rather than direct approaches, the music could facilitate the invitation, across the crowded disco floor, with the slower two-step grooves of Joyce Sims’s “Come into My Life” and Melissa Morgan’s “Do Me Baby,” which both felt better when slow dancing with a partner. Talking about emotions can be difficult for anyone, gay or straight, but the lyricism of many songs helped to figure out what was going on. “Hanging on a String” by the British band Loose Ends may have helped convey feelings more conducively than a frank conversation (“I’m not your plaything”). Another very popular track, Gwen Guthrie’s 1986 “Ain’t Nothin’ Goin’ On, But the Rent,” with its pounding bass introduction, called our bodies to move, to dance, and perform its assertive, pragmatic lyrics as we acted out the song’s message. The song struck a note at a time of high unemployment, poor housing conditions, and social inequality: “No romance without finance” and “A fly girl like me needs security.”

DJs would trawl through the crates of vinyl in records shops and at record fairs to seek out and obtain tracks that would resonate with the women’s scene, as well as to purchase popular tunes of the day. For many women DJs, this would be a search for positive lyrical content that did not express sexist stereotyping, pursuing tracks and musicians whose stance was progressive and conscious, and songs too that could be reinterpreted on the lesbian dancefloor for women who loved women. DJ Lynée Denise’s theory of DJ Scholarship sets out how the DJ is a social commentator, researcher, and archivist. She discusses the importance of developing a close reading of musical texts in order to develop our understanding of the music and then relate this to the context of how, where, and why the music is made, and its historical place. This research can then be transmitted to the dancers and shared through the tracks chosen and the flow of the mixes. Women DJs would plan their sets in order to present a playlist of great tracks for the club night experience, spending hours deciding on the musical blend and flow for the night, to then share with the women at the club. Adding to their collections, they visited record shops with their wants lists, seeking out the latest or rarest track to add to their bag of vinyl. The women had to hold their ground in the male-dominated spaces of these specialist shops, jostling with the other crate diggers to get the tracks touched and played, and to ascertain whether to make the purchase or not. The Nzinga Soundz DJ June Reid recounts her experiences:

“[I]nitially the men behind the counter would not take me seriously as I jostled with the predominantly ‘proper’ male customers at the counter.” As she became known, however, as someone who spends serious amounts of money, they would pre-select tracks for her to listen to prior to arrival, just as they do for men. Crucially, they knew that music policy of Nzinga Soundz did not permit playing any “slack tunes,” lyrics that debase women, or music that promoted violence. Only the best, the most conscious and uplifting tunes, were reserved. (qtd. in Rosenior-Patten and Reid 138)

The DJ sets were crafted sonic journeys from the early stages of warming up the crowd, to drawing in women to the dancefloor, and dropping known and unknown songs in contrapuntal dialogue with the dancers.

Conclusions

Women put their time and efforts into creating cultural, sensual spaces where they could get together through music. Jen Jack Gieseking describes the connections that lesbians made and make with each other as constellations.

… constellations as an alternative production of space that are born from and inspire alternative productions of urban political economy … constellations … are one queer feminist example of how people resist succumbing to precarious politics and economics of neoliberal capitalism. (13)

I extend this notion of the constellation to the lesbian sonic constellations in London in the 1980s and 1990s, where networks of women worked and created music and musical events for each other. Constellations expanded outwards from the DJs’ research, crate digging, and selection of tracks for the night, to the promoters’ energies spent putting on nights, and to the women writing, making, and producing music. The work was more often than not unpaid or underpaid, but was a way women could connect with each other through music. Women created and became part of temporal constellations as they moved to the club, and to the emotion and intensity of the dancefloor. These dynamic constellations of women seeking out other women and music recurred on a weekly or monthly basis, or were rare one-off events. Vibrant constellations of women connected on those transitory dancefloors, recognizing each other and the tracks they moved to, meeting strangers, and grooving to new tunes.

Terry Castle speaks of the erasure of lesbians in Western histories, providing examples of the lesbian as seen and not seen—a phantom in plain sight:

When it comes to lesbians … many people have trouble seeing what’s in front of them. Lesbian remains a kind of “ghost effect” in the cinema world of modern life: elusive, vaporous, difficult to spot – even when she is there, in plain view, mortal and magnificent, at the centre of the screen. Some may even deny that she exists at all. (2)

Ignored and erased from this spectral lesbian history are the lesbian singers, songwriters, musicians, and labels. The track “Freedom” by African American singer and songwriter Linda Tillery was a hit on the straight rare groove scene and the women’s scene, and was bought and sold for high prices in the UK. Unknown and unheralded was the fact that her record label, Olivia, was launched and run by lesbian-feminists. This gave her the creative space to write, record, produce, and distribute her work as a lesbian. We see how lesbians used cultural and political activism to create music, spaces, and environments, re-defining small corners of the world for ourselves and reaching other constellations of radical practice.

In our leisure time, these interior spaces, the sounds, mingling with other lesbian bodies, the music, and space of the dancefloor becomes a nexus of defiance and joy. This is in contrast to the many spaces that are not neutral, are oppressive: sometimes we can’t even wriggle our bodies, flex a leg, shake that bootie. Stepping out onto the dancefloor is a statement, being out on the dancefloor is a statement, being a queer body out on the dancefloor is liberating. Reclaiming space on the safe dancefloor, queer bodies connect, across the crowded disco floor, eyes meeting, bodies moving in time with the music and with each other’s rhythms, grooving, connecting somatically and sonically through the physicality of the low-end frequencies of the bass and the drum. I borrow here from Sara Ahmed’s notion of “wiggle room”:

[Y]ou might go and find a lesbian bar or queer space; it can be such a relief. You feel like a toe liberated from a cramped shoe: how you wiggle about! And we need to think about that: how the restriction of life when heterosexuality remains a presumption can be countered by creating spaces that are looser, freer, not only because you’re not surrounded by what you are not but because you are reminded there are many ways to be. Lesbian bars, queer space: wiggle room. (Ahmed 219)

Discussing the erasure of lesbian experiences, Ahmed talks of the sanctuary that can be found in lesbian and queer spaces and the freeing up, emotionally, and physically, that these spaces offer. Lesbians collected, shared, and danced to music from the time. The DJs selected the tracks, and the spaces were transformed into queer sound fields. Otherwise heterosexually-themed tunes, when consumed, played, and danced to in lesbian and queer spaces, were reimagined as queer texts. Lesbians repurposed the straight narratives from the songs as we moved our bodies together on our dancefloors to these grooves. In the oral history project, From a Whisper to a Roar, Yvonne Taylor of Sistermatic describes the South London Women’s Centre nights:

We bought everything and cooked the food, made the café respectable, made the games room more appealing and then made the club room look like a club room so we could see each other. And we played a whole variety of music so we didn’t have to listen to pop music. So we played old school soul, Aretha Franklin, anything that was rare groove, reggae, lover’s rock. So, basically, everyone was welcome. We had this whole room full of adiverse group of women who, for aminute, were united about the music.

Going back to these scraps of ephemera and the items that would otherwise have been discarded helps to reveal a vital underground scene, to remember, and to call up its protagonists and the many players who would pass these fragments from hand to hand. Women collected key information that would lead them to the clubs where they could meet other lesbians, find a sense of identity, and escape from the day-to-day hassles and traumas they experienced in daily queer life. Finding sanctuary where their sexuality did not have to be a close-held secret, lesbians traveled across the city, to the sounds on the dance floor, forming a collective body with other women through listening and dancing together. London offered a vibrant city where lesbians, queers, diverse non-conformist groups could find their tribes, where the sonic airwaves transmitted pirate radio jingles from passing cars, where our music scene crossed over geographic boundaries, north and south, to the dancefloor. We journeyed to be with other lesbians and to repurpose the lyrics of the songs for our uses, re-imagining the world away from the surveillance of the heteronormative world outside. The political significance of this research now, and the political activism of the lesbian club scene then, speaks to and of identity politics, racism, sexism, homophobia, queer history, marginalized lives. Common threads recur, linking those times to today. We now have the vantage point of being able to look back with a more capacious language, and understandings that have developed and become more inclusive over time. Academic and popular writing on nightclubbing too often ignores women’s contributions to the scenes they helped to build. Although LGBTQI+ cultures and communities have increasing visibility in the West, looking back can make visible a history of diverse sub-scenes that flourished in London at the end of the twentieth century.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author (s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Katherine Griffiths

Katherine Griffiths is a former and some-time DJ. She played rare groove at gigs and parties in London, Manchester, and Paris in the 1980s and 1990s on the lesbian and straight club scenes. She is currently reading her PhD in history at Royal Holloway University of London – tentatively titled “Going Out, Coming Out, Playing Out.” Using queer oral history, cultural geography, and an engagement with archives and material culture, this is an exploration and recouping of the lesbian club scene in London in the 1980s and 1990s that Black and white women created on the margins of this vibrant city.

Notes

1. For example, the works of Gilbert, Haslam, Lawrence, and Melville are important histories of clubbing but pay little attention to Black women, queer women, Black and white lesbians, and their various contributions, involvement, and consumption of music in the club environment, and their active work, creativity, and labor. This continues the narrative of club cultures that it is male trailblazers and innovators who are the experts and significant players. This perpetuates the flawed histories, and non-inclusive histories, of popular music, erasing key protagonists based on gender. Popular books such as How to DJ Properly (Broughton and Brewster) continue the erasure of women by referring throughout to the DJ as “he.”

2. The scene was variously referred to, at the time, as the “lesbian scene” and as the “women’s scene.” This took into consideration the varied nights and distinguished the scene from mixed gay or gay events. Women’s nights were attended by straight women, feminists, bisexual women, and women who slept with women who did not identify using the term “lesbian.” The word “lesbian” was also seen by some Black women and some working-class women as terminology associated with white, middle-class lesbian feminists. There was already a women’s scene in London that had existed for decades in subterfuge (e.g. the private members club Gateways in Chelsea and the Sols Arms in central London).

3. John Willsteed discusses ephemera collected from an alternative underground music scene in Brisbane and how curating and exhibiting these objects conjured up memories in attendees where they were exhibited.

4. Riseman focuses on his research of transgender Australians, some activists and others not. His interviewees had each amassed personal archives that he proposes are ways of affirming trans identities in the context of transphobia and secrecy, hence “evidence of me” When these are put together with other archives, formal documents, and oral histories, and then shared, the “nexus” becomes a community resource and “evidence of us.”

5. Bradley’s accounts of the contribution of Black singers and musicians to the London and British music scenes are crucial in-depth histories.

6. Elaine McKenzie went on to open the Southopia bar in South London after the Glass Bar closed.

Works Cited

- Ahmed, Sara. Living a Feminist Life. Duke UP, 2017.

- Bennett, Andy, and Paula Guerra, editors. DIY Cultures and Underground Music Scenes. Routledge, 2020.

- Bradley, Lloyd. Bass Culture: When Reggae Was King. Penguin, 2001.

- Bradley, Lloyd. 100 Years of Black Music in the Capital. Serpent’s Tail, 2011.

- Broughton, Frank, and Bill Brewster. How to DJ (Properly): The Art and Science of Playing Record; [Now Includes Digital Djing]. Reissued, Bantam Press, 2006.

- Castle, Terry. The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture. Columbia UP, 1993.

- Cook, Terry. “Evidence, Memory, Identity, and Community: Four Shifting Archival Paradigms.” Archival Science, vol. 13, no. 2, June 2013, pp. 95–120. Doi: 10.1007/s10502-012-9180-7

- Cvetkovich, Ann. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Duke UP, 2003.

- “DJ Lynée Denise.” DJ Lynée Denise Accessed May 17, 2023. www.djlynneedenise.com/.

- Frith, Simon. “Music and Identity.” Questions of Cultural Identity, edited by Stuart Hall and Paul du Gay, Sage, 1996, pp. 108–27.

- From a Whisper to a Roar. Oral History Archive, 2020, https://www.whisper2roar.org.uk/oral-history-archive/.

- Gieseking, Jen Jack. A Queer New York: Geographies of Lesbians, Dykes, and Queers, 2020.

- Gilbert, Jeremy, and Ewan Pearson. Discographies: Dance Music, Culture, and the Politics of Sound. Routledge, 1999.

- Gilroy, Paul. Small Acts: Thoughts on the Politics of Black Cultures. Serpent’s Tail, 1993.

- Hartman, Saidiya V. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women and Queer Radicals. Serpent’s Tail, 2021.

- Haslam, Dave. Life After Dark: A History of British Nightclubs & Music Venues. Simon & Schuster, 2017.

- Henriques, Julian. Sonic Bodies: Reggae Sound Systems, Performance Techniques, and Ways of Knowing. Continuum, 2011.

- Henry, William “Lez,” and Matthew Worley, edited by Narratives from Beyond the UK Reggae Bassline: The System is Sound. Palgrave Macmillan, 2021.

- Johnson, Linton Kwesi. Time Come: Selected Prose. Main Market edition, Picador, 2023.

- Lawrence, Tim. Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980-1983. Duke UP, 2016.

- Melville, Caspar. It’s a London Thing: How Rare Groove, Acid House and Jungle Remapped the City. Manchester UP, 2020.

- Mills, Dana. Dance and Politics: Moving Beyond Boundaries. Manchester UP, 2017.

- Paulette. Personal interview. 20 May 2023.

- Riseman, Noah. “Finding ‘Evidence of me’ Through ‘Evidence of us’: Transgender Oral Histories and Personal Archives Speak.” New Directions in Queer Oral History: Archives of Disruption, edited by Clare Summerskill, Amy Tooth Murphy, and Emma Vickers, Routledge, 2022, pp. 59–70.

- Rosenior-Patten, Lynda, and Reid. June “The Story of Nzinga Soundz and the Women’s Voice in Sound System Culture.” Narratives from Beyond the UK Reggae Bassline, edited by William “Lez” Henry and Matthew Worley, Palgrave Macmillan, 2021, pp. 125–42.

- Sharpe, Christina. Ordinary Notes. DB originals, 2023.

- Summerskill, Clare, Amy Tooth Murphy, and Emma Vickers, editors. New Directions in Queer Oral History: Archives of Disruption. Routledge, 2022.

- Valentine, Gill. “(Hetero)sexing Space: Lesbian Perceptions and Experiences of Everyday Spaces.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 11, no. 4, Aug. 1993, pp. 395–413. Doi: 10.1068/d110395

- Warren, Emma. Dance Your Way Home: A Journey Through the Dancefloor. Faber & Faber, 2023.

- Willsteed, John. “Here Today: The Role of Ephemera in Clarifying Underground Culture.” DIY Cultures and Underground Music Scenes, edited by Andy Bennett and Paula Guerra, Routledge, 2019, pp. 160–70.

Films

- Rebel Dykes. Directed by Siân A Williams and Harri Shanahan, Riot Productions, 2021.Fiddler on the Roof. Directed by Norman Jewison, United Artists, 1971.

Discography

- Gee, Lorna. “Three Week Gone (Mi Giro).” Ariwa Records, 1984. Vinyl.

- Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. “The Message.” Sugar Hill Records, 1982. Vinyl.

- Guthrie, Gwen. “Ain’t Nothin’ Goin’ on but the Rent.” Polydor, 1986. Vinyl.

- Loose Ends. “Hanging On a String (Contemplating).” Virgin Records, 1984. Vinyl.

- Knuckles, Frankie, and Satoshi Tomie. “Tears.” FFRR, 1989. Vinyl.

- Morgan, Melissa. “Do Me Baby.” Capitol, 1986. Vinyl.

- Phillips, Esther. “Home Is Where the Hatred Is.” KUDU, 1970. Vinyl.

- Scott-Heron, Gill. “Johannesburg.” Arista, 1975. Vinyl.

- Simms, Joyce. “Come Into My Life.” Sleeping Bag Records, 1987. Vinyl.

- Sledge, Sister. “We Are Family.” Cotillion, 1979. Vinyl.

- Topol. “If I Were a Rich Man.” Fiddler on the Roof, written by Sheldon Harnick and Jerry Bock, MFP, 1967, track 3. Vinyl.

- Wonder, Stevie. “Black Man.” Songs in the Key of Life, Motown, 1976, side 3, track 3. Vinyl.