Abstract

Objective: The objective of this analysis was to compare adherence at 6 months and 12 months across levothyroxine formulations for patients with hypothyroidism.

Methods: This retrospective analysis utilized insurance claims data from a commercially insured population from January 1, 2000 through March 31, 2016. Patients were included if they were diagnosed with hypothyroidism and initiated treatment with generic levothyroxine, Levoxyl, Synthroid, Unithroid, or Tirosint. Patients were excluded if they were younger than age 18, were diagnosed with thyroid cancer, received a prescription for liothyronine, or did not have continuous insurance coverage over the study period. Adherence, defined by the proportion of days covered (PDC) ≥ 80%, was examined using multivariable analyses for both 6 and 12 months post-initiation on therapy

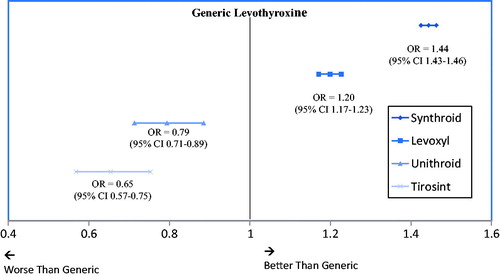

Results: The study identified 580,331 patients who fit the study criteria. At 6 months, 40.3% of patients were found to be non-adherent, while 51.9% were non-adherent at 12 months. Synthroid was associated with significantly higher adherence compared to all other levothyroxine formulations at both 6 and 12 months. Compared to generic levothyroxine, the likelihood of being adherent at 12 months was highest for Synthroid (OR = 1.44; 95% CI = 1.43–1.46), followed by Levoxyl (OR = 1.20 95% CI = 1.17–1.23). Tirosint and Unithroid were associated with significantly lower adherence at 12 months compared to generic levothyroxine (OR = 0.65; 95% CI = 0.57–0.75 and OR = 0.79; 95% CI = 0.71–0.89, respectively).

Conclusions: This large, retrospective real-world study demonstrated that adherence to levothyroxine remains a concern among patients with hypothyroidism, and that differences in adherence may exist across levothyroxine formulations.

Introduction

Hypothyroidism is a common condition, affecting 4.6% the US populationCitation1, and the leading cause of hypothyroidism, autoimmune thyroiditis, is the most prevalent type of autoimmune disease in the USCitation2,Citation3. Thyroid function potentially affects every bodily cell and organ, and the signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism are, consequently, many and variable by individualCitation4,Citation5. Some of the more frequent symptoms of hypothyroidism include fatigue, constipation, weight gain, dry skin, and goiterCitation6. Hypothyroidism has been shown to have an association with rheumatoid arthritis, pernicious anemia, Addison’s disease, type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, gestational diabetes, psoriatic arthritis, lupus erythematosus, celiac disease, and vitiligoCitation7–11.

The standard treatment for hypothyroidism is therapy with the synthetic hormone levothyroxineCitation12, which is available in branded and generic formsCitation13. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers generic and branded formulations to be therapeutically equivalentCitation14. Levothyroxine is available as a tablet, soft gel capsule, and oral solution, with some evidence that the soft gel capsule releases the active ingredient more consistently and the soft gel capsule and oral solution may solve the malabsorption of the tablet when used with certain drugs or coffeeCitation15. Given the uniqueness of individual tablet formulations, the introduction of soft gel capsules and an oral solution, and uncertainty regarding the bioequivalence among tablets, the American Thyroid Association (ATA) and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) ‘… encourage the use of a consistent L-thyroxine preparation for individual patients to minimize variability from refill to refill’Citation16 (p. 1002).

Regardless of the formulation, levothyroxine must be taken at regular intervals consistently (e.g. daily, twice weekly, alternate days, or weekly), in order to normalize thyroid hormone levelsCitation17. Yet, after 5 years of levothyroxine therapy, ∼22% of patients have been reported to have abnormal thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels due to poor medication adherenceCitation17. A letter published more than a decade ago in The Lancet called for more research on levothyroxine adherence, arguing that the lack thereof signified “Something … gone seriously awry with the focus of medical research”Citation18 (p. 1558). To date, adherence to levothyroxine therapy among patients with hypothyroidism is still not well characterized. The current study aims to describe overall levothyroxine therapy adherence and to assess whether adherence is affected by formulation of levothyroxine.

Methods

Truven’s Health Analytics MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (CCAE) database, which ranged from January 1, 2000 through March 31, 2016, was used for this study. Truven’s CCAE database consists of the healthcare records of millions of commercially insured individuals who are covered by fully- or partially-capitated, fee-for-service health plans. As such, the database provides detailed costs, use, and outcomes data for healthcare services performed in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Medical claims are linked to outpatient prescription drug claims and person-level enrollment information. The data are fully de-identified and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant.

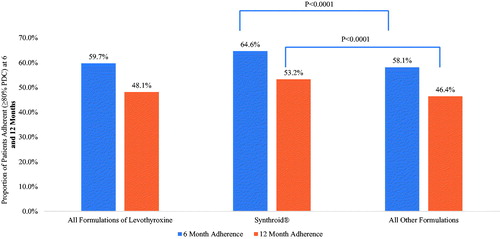

For inclusion in the study, patients were required to have received at least one diagnosis of hypothyroidism (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] of 243.xx or 244.xx or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] of E00.9, E01.8, E03.x, or E89.0), with the first such date identified as the diagnosis date. Given the diagnosis date, patients were also required to have initiated any levothyroxine formulation over the time period from 1 year prior through 1-year post-diagnosis date, with the first such date identified as the index date. Patients were excluded if they were younger than age 18 as of the index date or if they received a diagnosis of thyroid cancer (ICD-9-CM of 193, ICD-10-CM of C73) or filled a prescription for liothyronine at any time. Patients were also required to have continuous insurance coverage over the period from the start of the pre-period through the end of the post-period. The final sample consisted of 580,331 patients, and illustrates the study flow chart.

Figure 1. Study flowchart. The biggest loss in patients was due to the eligibility requirement, with approximately 85% of individuals not having 12 months of continuous enrollment. Abbreviations. M, million; Pts, patients; Tx, treatment; HT, hypothyroidism; Dx, diagnosis; THR, thyroid hormone replacement.

The study focused on adherence of levothyroxine by comparing (1) Synthroid to all other formulations; (2) individual formulations of levothyroxine; and (3) individual branded formulations to generic levothyroxine. Specifically, adherence for Synthroid was compared to all other formulations and adherence for each individual formulation (Levoxyl, Synthroid, Tirosint, and Unithroid and generic levothyroxine) was examined at both 6 and 12 months. Furthermore, the likelihood of being adherent at 1 year was examined for each individual branded formulation compared to generic levothyroxine. Adherence was calculated using the proportion of days covered (PDC), a measure recommended by both the Pharmacy Quality AllianceCitation19 and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid servicesCitation20. Specifically, PDC is defined as the percentage of unique days an individual received the levothyroxine formulation in the time period of interest, and was calculated at the class level for all formulations of levothyroxine combined, for patients treated with Synthroid and all other formulations combined, and for each formulation individually. Consistent with previous research, patients were categorized as adherent if they achieved a PDC threshold of ≥80%Citation20,Citation21.

Differences between comparators were examined using analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests, while logistic regressions compared adherence to generic levothyroxine relative to each of the individual drugs of interest. These multivariable analyses used levothyroxine adherence as the dependent variable and controlled for patient characteristics (age, sex, region of residence, and insurance coverage), pre-period general health status, and year of index date. General health was proxied by the Charlson Comorbidity Score, which was scored on a scale of 0–29 based upon the presence of comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, hypertension, liver disease, and malignanciesCitation22,Citation23.

The robustness of the findings was tested using two sensitivity analyses. First, the proportion of patients who were adherent were re-examined using alternative PDC cut-offs of 70% and 90%. In addition, all analyses were conducted for the sub-sets of patients who were incident treated, defined as those patients whose initial receipt of levothyroxine occurred after diagnosis of hypothyroidism, and those who were prevalent treated, defined as those patients whose initial receipt of levothyroxine occurred before their diagnosis of hypothyroidism. All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (Cary, NC). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

presents descriptive statistics for the 580,331 individuals included in the study. Most patients were female (73.94%), and the mean age was 52 years (SE = 0.02). Patients most commonly resided in the Southern (38.78%) or North Central (24.80%) regions of the country, and most were covered by preferred provider organizations (PPO) insurance (50.34%). Patients were most commonly identified as having none (35.88%) or one (30.55%) condition examined in the Charlson Comorbidity Score, with 11.95% of patients having a score of four or above. Patients were most commonly prescribed generic levothyroxine (67.93%) or Synthroid (25.05%) as their index medication.

Table 1. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics at baseline.

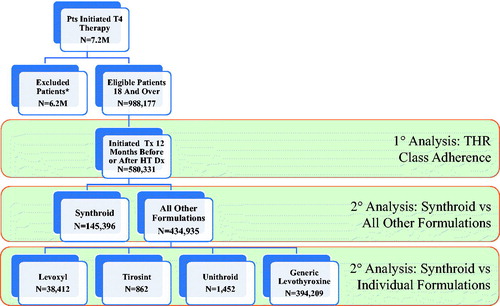

focuses on adherence at 6 and 12 months for all formulations of levothyroxine, as well as for Synthroid, compared to other formulations. As expected, adherence was lower at 12 months than at 6 months. Overall, less than two-thirds of patients (59.7%) were adherent to levothyroxine over the first 6 months post-initiation, and less than half (48.1%) were adherent over the first 12 months post-initiation. Compared to all other formulations of levothyroxine, use of Synthroid was associated with significantly higher rates of patients identified as adherent over both the first 6 months (64.6% vs 58.1%; p < .0001) and 12 months (53.2% vs 46.4%) post-index date.

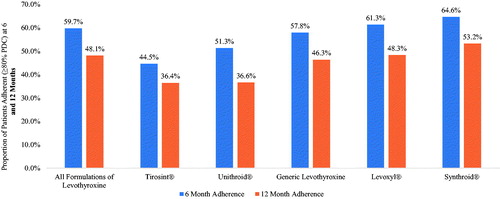

While focuses on Synthroid compared to the aggregation of all other formulations combined, illustrates adherence at 6 months and 12 months for individual formulations of levothyroxine. The results from support the findings from . Specifically, while illustrates that adherence at 6 and 12 months was significantly higher for Synthroid compared to other formulations combined, shows that adherence over both these time horizons was highest for Synthroid compared to each individual formulation. Furthermore, at both 6 and 12 months, patients who initiated on Tirosint were found to be least adherent.

Figure 3. Proportion of patient adherent (≥80% PDC) at 6 and 12 months by individual formulations of levothyroxine.

presents results from multivariable analyses that calculate the odds of being adherent for each individual branded levothyroxine formulation relative to generic levothyroxine. Generic levothyroxine was chosen as the reference group, since it was the most commonly prescribed formulation. Compared to those treated with generic levothyroxine, patients who initiated therapy on Tirosint or Unithroid were less likely to be adherent (35% or 21% less, respectively; both p < .0001), while patients who initiated on Levoxyl or Synthroid were more likely to be adherent compared to those who initiated on generic levothyroxine (20% or 44% more likely, respectively; both p < .0001).

Figure 4. Odds of being adherent (≥80% PDC) at 12 months compared to generic levothyroxine. Results from multivariable logistic regressions which control for patient age, sex, region, insurance, index year, and Charlson Comorbidity Score. Abbreviations. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

As a test of the sensitivity of the results, analyses were conducted again for the sub-sets of incident treated patients (n = 290,566) and prevalent treated patients (n = 289,765), as well as for the alternative PDC thresholds of 70% and 90%. The findings were generally not sensitive to these alternative specifications. For example, when comparing Synthroid to generic levothyroxine over the 1-year post-period, Synthroid use was found to be associated with a higher probability of adherence among both the new initiators (OR = 1.46; 95% CI = 1.43–1.48) and those who had previously been prescribed levothyroxine (OR = 1.45; 95% CI = 1.42–1.48), and the result is similar to results for the sample as a whole (OR = 1.44; 95% CI = 1.43–1.46). The percentage of overall patients identified as adherent ranged from 38.41% when the PDC cut-off was ≥90% to 55.07% when the PDC cut-off was ≥70%, with patients treated with Synthroid having the highest percentage of adherent patients at all three adherence thresholds identified. The results of the sensitivity analyses are provided in Supplementary Appendices A and B.

Discussion

Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism recommend the consistent use of the same levothyroxine formulation, regardless of which formulation is takenCitation16. The present findings indicate that non-adherence is high with every levothyroxine product. However, patients in this study were significantly more likely to remain adherent when taking certain formulations relative to others.

Slightly more than half (59.7%) of the users of levothyroxine of any type were adherent at 6 months in the present study, while somewhat less than half (48.1%) were adherent at 12 months (). These findings are roughly consistent with the World Health Organization (WHO) statement that, in developed countries, only 50% of patients with chronic diseases are adherent to their treatment regimensCitation24. This WHO statistic has been criticized for having its basis in only two studies published over 40 years agoCitation25. However, more recent research on seven chronic disease states has generally supported the 50% adherence rateCitation26. In studies of individuals with hypothyroidism, percentages of adherent patients have varied between 36.8% in studies using healthcare claims dataCitation26 to 78% based upon self-reportCitation27. While the exact percentages have varied, these previous studies and the present results show that adherence remains a concern, and efforts should focus on improving adherence in this class.

Relative to all other medications considered, Synthroid was associated with the highest adherence rates at both 6- and 12-months. Descriptive analyses showed that, compared to all other formulations combined, both the 6- and 12-month adherence rates were significantly higher for Synthroid. Multivariable analyses comparing Synthroid to generic levothyroxine were consistent with the descriptive statistics, with patients who initiated on Synthroid 44% more likely to achieve a PDC threshold of ≥80% at 12 months. Patients were also found to be significantly more likely to be adherent if using Levoxyl, compared to generics.

Although the data do not explain why patients are more adherent when prescribed Levoxyl or Synthroid compared to generic levothyroxine, there are a number of theories. The improved adherence associated with Levoxyl and Synthroid may result from a lack of biological or therapeutic equivalence among generic formulations of levothyroxine; a finding which has been reported in some previous researchCitation28,Citation29. Preceding investigations across various disease states have found patients more likely to adhere to brand names than to generic drugs for a number of reasons, including patient biasesCitation30, patient confusion related to the physical appearance of the pillsCitation31, differences in dosage optionsCitation32, and the nocebo effect of adverse effects associated with use of generic medications which cannot be explained by pharmacological factorsCitation33. Another possible explanation is the presence of patient support, and saving programs available through the Synthroid website may also assist patients in receipt and use of this medicationCitation34. Previous research that has focused on hypothyroidism has also found that, in general, adherence is significantly higher with branded than with generic drug useCitation35.

In contrast to the results for Synthroid and Levoxyl, the use of Unithroid or Tirosint was associated with substantially reduced odds of achieving an adherence threshold of ≥80%, compared to the use of generic levothyroxine. In general, such contradictory results are puzzling. One potential explanation of these difference in results may be the quality, access to, and/or ease of use of copay assistance programs. While the research cited above suggests that adherence should be improved with the use of branded medications, other research which has examined multiple disease states found that there may be conflicting results comparing adherence between branded and generic medicationsCitation35.

By virtue of its size and geographically diverse data, use of the MarketScan database provides results that are applicable to most commercially insured patients with hypothyroidism in the US. However, the study findings should be viewed in the context of certain limitations which stem from the use of claims data. First, claims data can provide only an image of the financial transactions between healthcare (outpatient, inpatient, and pharmacy) facilities and payers (insurance companies). Without fully documented interactions between patients and physicians, we cannot know if patients received or used services or products, and the lack of such evidence, in turn, forces researchers to make assumptions. For example, the presence of a claim for a filled prescription does not necessarily indicate that the medication has been taken as prescribed or has been consumed at all. Moreover, any medications filled over-the-counter or provided as samples by the physician are not observable in the claims data. A second limitation of claims data research is that the researcher must use diagnostic codes rather than formal assessments to identify patients with a particular diagnosis. The presence of a diagnosis code on a medical claim does not guarantee the positive presence of a disease, as a diagnosis may be incorrectly coded or included as a rule-out criterion. To limit this bias, claims were required to have both a relevant diagnosis code and associated prescription fills. A third limitation is that claims only capture data that is required for adjudication. Other potentially important variables (e.g. income, education, disease severity, smoking status, etc.) could not be controlled for, and may, thus, have biased the results. Furthermore, the lack of laboratory test results in our data precludes an examination between levothyroxine adherence and patient TSH. Finally, the results from this analysis describe only associations. No causal inference can be drawn from any of the analyses described herein.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this large, retrospective analysis of claims data demonstrated that adherence to levothyroxine for patients with hypothyroidism remains a concern. In our analysis, levothyroxine formulations were shown to impact adherence. Patients who initiated on Synthroid were associated with the highest likelihood of adherence at both 6 and 12 months. Results were robust to sensitivity analyses. Based on our findings, future research should focus on adherence drivers and interventions to improve adherence in this patient population.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Support for this study was provided by AbbVie Inc. AbbVie participated in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing, reviewing, and approving the publication.

Declaration of financial/other interests

ZH was an employee of AbbVie Inc and held stock in AbbVie at the time this study was conducted. SRM and SW are current employees and stockholders of AbbVie Inc. SW and VG are consultants for AbbVie. CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Truven Health Analytics. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the authors with the permission of Truven. Copyright © 2018 Truven Health Analytics LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Appendix_A_and_B.docx

Download MS Word (18.1 KB)Acknowledgments

Michael Treglia of HealthMetrics Outcomes Research, LLC provided medical writing and editing services in the development of this publication. AbbVie provided funding for this work.

References

- Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:489-99

- Berber E. Causes of hypothyroidism [Internet]. Montclair, NJ: EndocrineWeb; 2014 [cited March 9, 2018]. Available from: https://www.endocrineweb.com/conditions/hypothyroidism/causes-hypothyroidism. [Last accessed 13 November 2017]

- Ferrari SM, Fallahi P, Vita R, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in thyroid autoimmunity. PPAR Res 2015;2015;232818

- Klein I, Levey GS. Unusual manifestations of hypothyroidism. Arch Intern Med 1984;144:123-8

- Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the American Thyroid Association task force on thyroid hormone replacement. Thyroid 2014;24:1670-751

- El-Shafie KT. Clinical presentation of hypothyroidism. J Family Community Med 2003;10:55-8

- Bouchou K, André M, Cathébras P, et al. Thyroid disease and multiple autoimmune syndromes. Clinical and immunogenetic aspects apropos of 11 cases. Rev Med Intern 1995;16:283-7

- Lazúrová I, Benhatchi K, Rovenský J, et al. Autoimmune thyroid disease and autoimmune rheumatic disorders: a two-sided analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009;1173:211-16

- Lazúrová I, Benhatchi K. Autoimmune thyroid diseases and nonorgan-specific autoimmunity. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2012;122(Suppl 1):55-9

- Giorda CB, Carnà P, Romeo F, et al. Prevalence, incidence and associated comorbidities of treated hypothyroidism: an update from a European population. Eur J Endocrinol 2017;176:533-42

- Kasperlik-Zaluska A, Czarnocka B, Czech W. High prevalence of thyroid autoimmunity in idiopathic Addison’s disease. Autoimmunity 1994;18:213-16

- Garber AJ. Treat-to-target trials: uses, interpretation and review of concepts. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014;16:193-205

- Thyroid hormone treatment [Internet]. Falls Church, VA: American Thyroid Association; 2017 [cited March 9, 2018]. Available from: https://www.thyroid.org/thyroid-hormone-treatment/ [Last accessed June 16, 2018]

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Orange book: approved drug products with therapeutic equivalence evaluations, 37th ed. Rockville, MD: US Dept. of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Office of Pharmaceutical Science, Office of Generic Drugs; 2017

- Vita R, Fallahi P, Antonelli A, et al. The administration of L-thyroxine as soft gel capsule or liquid solution. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2014;11:1103-11

- Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Endocr Pract 2012;18:988-1028

- Scavone C, Sportiello L, Cimmaruta D, et al. Medication adherence and the use of new pharmaceutical formulations: the case of levothyroxine. Minerva Endocrinol 2016;41:279-89

- Crilly M. Thyroxine adherence in primary hypothyroidism. Lancet 2004;363:1558

- Pharmacy Quality Alliance. 2018 PQA medication quality measures in the health insurance marketplace [Internet]. Alexandria, VA: Pharmacy Quality Alliance; 2017 [cited March 9, 2018]. Available from: https://pqaalliance.org/measures/qrs.asp [Last accessed June 16, 2018]

- Medicare Part D quality measures [Internet]. Alexandria, VA: Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy; 2014 [cited March 9, 2018]. Available from: http://www.amcp.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=18900 [Last accessed June 16, 2018]

- Hanemaaijer S, Sodihardjo F, Horikx A, et al. Trends in antithrombotic drug use and adherence to non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants in the Netherlands. Int J Clin Pharm 2015;37:1128-35

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613-19

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130-9

- World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017 [cited March 9, 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf [Last accessed 13 November 2017]

- Mathes T, Pieper D, Antoine S-L, et al. 50% adherence of patients suffering chronic conditions–where is the evidence? Ger Med Sci 2012;10:Doc 16

- Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Fouayzi H, et al. Comparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditions. Pharmacotherapy 2008;28:437-43

- Crilly M, Esmail A. Randomised controlled trial of a hypothyroid educational booklet to improve thyroxine adherence. Br J Gen Pract 20015;55:362-8

- Carswell JM, Gordon JH, Popovsky E, et al. Generic and brand-name L-thyroxine are not bioequivalent for children with severe congenital hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:610-17

- Mayor GH, Orlando T, Kurtz NM. Limitations of Levothyroxine bioequivalence evaluation: analysis of an attempted study. Am J Ther 1994;2:417-32

- Håkonsen H, Eilertsen M, Borge H, et al. Generic substitution: additional challenge for adherence in hypertensive patients? Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:2515-21

- Kesselheim AS, Misono AS, Shrank WH, et al. Variations in pill appearance of antiepileptic drugs and the risk of nonadherence. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:202-8

- Sander JW, Ryvlin P, Stefan H, et al. Generic substitution of antiepileptic drugs. Expert Rev Neurother 2010;10:1887-98

- Weissenfeld J, Stock S, Lüngen M, et al. The nocebo effect: a reason for patients’ non-adherence to generic substitution? Pharmazie 2010;65:451-6

- Hypothyroidism symptom profiler [Internet]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc.; 2017 [cited March 9, 2018]. Available from: https://www.synthroid.com/support/hypothyroidism-resources [Last accessed 13 November 2017]

- Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Fouayzi H, et al. Medication adherence and the use of generic drug therapies. Am J Manag Care 2009;15:450-6