Abstract

Objective: To compare rehospitalizations in patients with schizophrenia treated with paliperidone palmitate (PP1M) vs oral atypical antipsychotics (OAAs), with a focus on young adults (18–35 years).

Methods: The Premier Healthcare database (January 2009–December 2016) was used to identify hospitalizations of adults (≥18 years) with schizophrenia treated with PP1M or OAA between September 2009 and October 2016 (index hospitalizations). Rehospitalizations were assessed at 30, 60, and 90 days after each index hospitalization in young adults and in all patients. Proportions of index hospitalizations resulting in rehospitalization were reported and compared between groups using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results: A total of 8578 PP1M and 306,252 OAA index hospitalizations were included. Hospitalized young adults treated with PP1M (n = 3791) were more likely to be seen by a psychiatrist (94.0% vs 90.0%), and had a longer length of stay (12.5 vs 8.6 days) compared to hospitalized young adults treated with OAA (n = 96,502). Following their discharge, young adults receiving PP1M during an index hospitalization had a 25–27% lower odds of rehospitalization within 30, 60, and 90 days compared to young adults receiving OAAs (all p < .001). Similarly, when observing all patients, those receiving PP1M during an index hospitalization had 19–22% lower odds of rehospitalization within 30, 60, and 90 days compared to those receiving OAAs (all p < .001).

Conclusions: Following a hospitalization for schizophrenia, PP1M treatment was associated with fewer 90-day rehospitalizations among young adults (18–35 years) relative to OAA treatment. This finding was also observed in other hospitalized adults with schizophrenia.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a debilitating chronic mental illness characterized by delusional thinking, social withdrawal, and hallucinations. The onset of schizophrenia symptoms typically occurs in the early-to-mid 20s for men and late 20s for women, and the disease entails lifelong consequencesCitation1,Citation2. This leads to a US lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia of ∼1% in the adult populationCitation1,Citation3,Citation4.

The risk of clinical relapse in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia can be effectively reduced with an antipsychotic (AP) agentCitation5. However, poor adherence to APs is an important limitation that hinders their effectiveness, particularly in young patients who tend to have poor insight into illness and higher rates of substance abuseCitation6–8. Non-adherence may have detrimental long-term consequences, as the progression of schizophrenia is particularly fast within the first few years (i.e. 2–5 years) following disease onsetCitation9–11. Therefore, early interventions with medications that improve patients’ adherence during this critical period may impart durable and long-term benefits to patients with schizophreniaCitation9,Citation12,Citation13. Long-acting injectables (LAIs), like once-monthly paliperidone palmitate (PP1M), increase medication adherence, reduce symptoms, and reduce the risks of experiencing relapses and rehospitalizations compared to oral atypical APs (OAAs)Citation14–17. Previous studies suggested LAIs may be particularly beneficial for younger patients, but these were limited by low sample sizeCitation18, did not include a control groupCitation19, or were conducted outside of the USCitation20. Thus, there is a need for a comprehensive assessment of the impact of LAIs in young patients with schizophrenia in the US.

Although the effects of PP1M on the risk of relapse are well documentedCitation17,Citation21–24, there is limited real-world information on relapse that is specific to young adult populations with schizophrenia in the USCitation25. Rehospitalizations, a parameter used as a quality-of-care measure for US providers and payersCitation26, are an important marker of relapse and disease burden in patients with schizophreniaCitation6,Citation27. Therefore, this retrospective claims-based study was conducted to compare rehospitalizations in patients with schizophrenia treated with PP1M vs OAA, with a focus on young adults (18–35 years old).

Methods

Data source

The Premier Perspective Comparative Hospital (Premier Inc., Charlotte, NC) database (January 2009 to December 2016), which encompasses detailed inpatient services from more than 700 hospitals nationwide in the US and over 680 million individual encounters, was used. Extracted data elements included demographics, hospital characteristics, visit-level information, detailed medication information, and actual costs from the hospital perspective. The database is de-identified and in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Study design

A retrospective study design, in which each patient could contribute more than once (i.e. at each selected hospitalizations), was used. Index hospitalizations were defined as a schizophrenia-related hospitalization (see Study population section for definition) during which PP1M or OAA was used to treat the patient (i.e. PP1M and OAA index hospitalizations, respectively) between January 2009 and October 2016. The index date was defined as the date of discharge of the index hospitalization ().

Figure 1. Overview of the study design. OAA, oral atypical antipsychotics; PP1M, once-monthly paliperidone palmitate. 1A potential index hospitalization was defined as hospitalizations meeting any one of the following criteria: (1) a primary or admitting diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD, version 9 [ICD-9] code 295.xx; ICD, version 10 [ICD-10] codes F20.xx, F21.xx, and F25.xx); (2) a primary or admitting diagnosis of a mental disorder (ICD-9 codes 290.xx–319.xx, excluding code 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F00–F99, excluding codes F20.xx, F21.xx, and F25.xx) and a secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9 code 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F20.xx, F21.xx, and F25.xx); or (3) a primary or admitting diagnosis of injury or poisoning (ICD-9 codes 800.xx–999.xx; ICD-10 codes S00–T88) and a secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9 code 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F20.xx, F21.xx, and F25.xx).

![Figure 1. Overview of the study design. OAA, oral atypical antipsychotics; PP1M, once-monthly paliperidone palmitate. 1A potential index hospitalization was defined as hospitalizations meeting any one of the following criteria: (1) a primary or admitting diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD, version 9 [ICD-9] code 295.xx; ICD, version 10 [ICD-10] codes F20.xx, F21.xx, and F25.xx); (2) a primary or admitting diagnosis of a mental disorder (ICD-9 codes 290.xx–319.xx, excluding code 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F00–F99, excluding codes F20.xx, F21.xx, and F25.xx) and a secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9 code 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F20.xx, F21.xx, and F25.xx); or (3) a primary or admitting diagnosis of injury or poisoning (ICD-9 codes 800.xx–999.xx; ICD-10 codes S00–T88) and a secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9 code 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F20.xx, F21.xx, and F25.xx).](/cms/asset/ba1b1ac7-b4a7-49d0-828b-758f5647fd5a/icmo_a_1512477_f0001_b.jpg)

OAA medication included aripiprazole, asenapine maleate, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine, quetiapine fumarate, risperidone, and ziprasidone. Schizophrenia-related hospitalizations with use of both PP1M and OAA were classified as PP1M. Patient characteristics were described as of the index hospitalization or during the index hospitalization (except for information related to prior schizophrenia-related hospitalizations; the baseline period). Rehospitalizations within the same facility for a given patient were analyzed 30, 60, and 90 days after the index date (i.e. the observation period; ). The analysis focused on two populations: a young adult population, defined as patients aged between 18–35 as of the index hospitalization, and the overall population, defined as all patients aged ≥18. For completeness, the older adults population (> 35 years old) was also analyzed.

Study population

Patients were required to have at least one schizophrenia-related index hospitalization during the study period, defined as a hospitalization with: (1) a primary or admission diagnosis of schizophrenia (International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision [ICD-9] code 295.xx; International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision [ICD-10] codes F20.xx, F21.xx, or F25.xx); (2) a primary or admission diagnosis of a mental disorder (ICD-9 codes 290.xx–319.xx, excluding code 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F00–F99, excluding codes F20.xx, F21.xx, or F25.xx) and a secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9 code 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F20.xx, F21.xx, or F25.xx); or (3) a primary or admission diagnosis of injury or poisoning (ICD-9 codes 800.xx–999.xx; ICD-10 codes S00–T88) and a secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9 code 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F20.xx, F21.xx, or F25.xx).

An index hospitalization meeting at least one of the following criteria was excluded: reported treatment with an LAI other than PP1M (i.e. first-generation: fluphenazine LAI, haloperidol LAI; second-generation: olanzapine LAI, risperidone LAI, paliperidone LAI, and aripiprazole LAI; and once-every-3-month paliperidone palmitate) prior to or during the index hospitalizations, or transfer to a psychiatric institution or death on discharge from the potential index hospitalization.

Patients were allowed to have more than one index hospitalization if they were hospitalized repeatedly at the same facility, and the hospitalizations were considered schizophrenia-related and were not excluded given the criteria above.

Study measures

The rate of all-cause rehospitalization and schizophrenia-related rehospitalization (i.e. with ≥1 admission, primary, or secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia [ICD-9 code 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F20.xx, F21.xx, or F25.xx]) after 30, 60, and 90 days of follow-up from discharge of index hospitalization constituted the study measures.

Statistical analysis

Means, standard deviations, and medians were used to describe continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables. Standardized differences were calculated to compare baseline characteristics between patients treated with PP1M vs OAA during index hospitalization (significance threshold of ≥10%)Citation28,Citation29. The standardized difference is an index which measures the effect size between two groups. It is calculated based on the difference in means between two groups divided by a function of the sum of the variances in the two groups, for both continuous and binary variablesCitation28,Citation29. A generalized estimating equation (GEE) model, with patient as a repeated measure, was used along with a logit link with a binomial distribution to estimate the odds of rehospitalization when PP1M vs OAA was used to treat the patient during index hospitalizationsCitation30. The model was implemented in SAS Enterprise Guide 7.11 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), using the Proc genmod procedureCitation31.

Odds of rehospitalization were first estimated using a univariate model (i.e. patient treated with PP1M vs OAA during index hospitalization). Then a multivariate model was used so that the odds of rehospitalization were adjusted for index treatment (i.e. patient treated with PP1M vs OAA during index hospitalization), age, sex, marital status (single or not), race or ethnicity (white or not), geographical region, payer (Medicaid or not), teaching hospital, year of index hospitalization (before 2012 or not), psychiatrist as attending doctor, severity of illness (major/extreme or not), suicide-related ICD codes (ICD-9: 300.9, V62.84, 960–979, E950–E959, E980–E989; ICD-10: F48.9, F99, R45.851, T36–T50, X71–X83, Y21–Y33), length of stay, total cost, number of months from prior hospitalization, and being admitted from law or court. All variables were obtained prior to or during an index hospitalization. The variables were selected based on clinical relevance, standardized difference at baseline, use in former studiesCitation17, and to ensure convergence of the multivariate model (based on the convergence criterion of the GEE parameter estimation)Citation31. Odds ratios (ORs) comparing PP1M vs OAA used to treat the patient during index hospitalizations were presented as a measure of effect along with 95% confidence intervals and p-values. No adjustments were made for multiplicity.

Results

Index hospitalization selection and patient population

There were 67,202 unique young adult patients whose index hospitalization(s) met all eligibility criteria, and 3133 and 65,401 of them had an index hospitalization during which PP1M (i.e. patient treated with PP1M during index hospitalization) or OAA (i.e. patient treated with OAA during index hospitalization) was used, respectively (patients could be in both groups if they had ≥1 PP1M and ≥1 OAA index hospitalizations, hence the sum of patients in both groups is greater than the total number of unique patients; ). There were 3791 and 96,502 index hospitalizations during which PP1M or OAA were used to treat patients, respectively, for a total of 100,293 index hospitalizations in the young adult population ( and ). In the overall population, a total of 199,690 unique patients had hospitalizations meeting all eligibility criteria, and 6980 and 195,793 of them had PP1M and OAA index hospitalizations, respectively (). These patients contributed a total 314,830 hospitalizations, among which 8578 were PP1M index hospitalizations and 306,252 were OAA index hospitalizations ( and ).

Figure 2. Identification of index hospitalizations. LAI, long-acting injectable; OAA, oral atypical antipsychotics; PP1M, once-monthly paliperidone palmitate; Hosp, hospitalization. 1A hospitalization was defined as having a schizophrenia diagnosis if it fulfilled one of the following conditions: (a) A primary or admitting diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD, version 9 [ICD-9] code 295.xx; ICD, version 10 [ICD-10] codes F20.xx, F21.xx, and F25.xx); (b) A primary or admitting diagnosis of a mental disorder (ICD-9 codes 290.xx–319.xx, excluding code 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F00–F99, excluding codes F20.xx, F21.xx, and F25.xx) and a secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9 code 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F20.xx, F21.xx, and F25.xx). 2The study period spanned January 2009 to December 2016 (inclusively), that is until the end of data availability. 3OAA medication included aripiprazole, asenapine maleate, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine, quetiapine fumarate, risperidone, and ziprasidone. 4Other LAIs included were first-generation: fluphenazine LAI, haloperidol LAI; second-generation: olanzapine LAI, risperidone LAI, paliperidone LAI, and aripiprazole LAI; as well as PP3M.

![Figure 2. Identification of index hospitalizations. LAI, long-acting injectable; OAA, oral atypical antipsychotics; PP1M, once-monthly paliperidone palmitate; Hosp, hospitalization. 1A hospitalization was defined as having a schizophrenia diagnosis if it fulfilled one of the following conditions: (a) A primary or admitting diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD, version 9 [ICD-9] code 295.xx; ICD, version 10 [ICD-10] codes F20.xx, F21.xx, and F25.xx); (b) A primary or admitting diagnosis of a mental disorder (ICD-9 codes 290.xx–319.xx, excluding code 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F00–F99, excluding codes F20.xx, F21.xx, and F25.xx) and a secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9 code 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F20.xx, F21.xx, and F25.xx). 2The study period spanned January 2009 to December 2016 (inclusively), that is until the end of data availability. 3OAA medication included aripiprazole, asenapine maleate, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine, quetiapine fumarate, risperidone, and ziprasidone. 4Other LAIs included were first-generation: fluphenazine LAI, haloperidol LAI; second-generation: olanzapine LAI, risperidone LAI, paliperidone LAI, and aripiprazole LAI; as well as PP3M.](/cms/asset/1fbba42d-e0c7-4350-a462-ad8494d8064b/icmo_a_1512477_f0002_b.jpg)

Table 1. Index hospitalizations per patient.

Table 2. Patient characteristics as of the index hospitalization.

Patient characteristics during index hospitalization(s)

In the young adult population, patients treated with PP1M during index hospitalization were younger than those treated with OAA during index hospitalization (i.e. 26.7 vs 27.2 years old; standardized difference: 10.4%), they comprised a higher proportion of males (i.e. 73.8% vs 67.7% male; standardized difference: 13.4%) and white patients (i.e. 35.2% vs 46.3%; standardized difference: 22.7%), were more frequently admitted from court/law enforcement (i.e. 7.5% vs 2.9%; standardized difference: 20.7%), were more likely to be seen by a psychiatrist (94.0% vs 90.0%, standardized difference: 14.7%), and had more frequent prior schizophrenia-related hospitalizations with OAA treatment (i.e. 27.2% vs 21.0% with ≥1 hospitalization in the past 5 months; standardized difference: 14.5%). Furthermore, they presented a paranoid type of schizophrenia more frequently (i.e. 34.9% vs 23.3%; standardized difference: 25.8), and they had a longer length of stay and a higher cost of stay during the index hospitalization (e.g. 20+ days: 14.5% vs 6.9%; standardized difference: 25.0%; ). Largely similar observations were made for patients in the overall population (). In both populations, a majority (∼ 90%) of patients treated with PP1M at index hospitalization received their index medication in or after 2012.

Odds of rehospitalization after index hospitalization

Prior to multivariate adjustment and in the young adult population, the rates of index hospitalizations resulting in all-cause and schizophrenia-related rehospitalization were consistently lower for patients treated with PP1M during index hospitalization compared to patients treated with OAA during index hospitalizations (i.e. all-cause rehospitalization at 30 days: 11.8% vs 15.5%, at 60 days: 16.7% vs 20.6%, and at 90 days: 21.0% vs 24.2%; ). Similar trends were observed in the overall population ().

Table 3. Rate of rehospitalization after index hospitalization, per age group, type of rehospitalization, and time since discharge from index hospitalization.

When performing univariate analysis (i.e. without adjustment, but accounting for the repeated measures), results paralleled the rates described in with smaller odds of rehospitalization for patients treated with PP1M during index hospitalization compared to patients treated with OAA during index hospitalization, for both the young adult and overall populations. For instance, in the young adult population, the odds of all-cause rehospitalization were 28–31% lower in the 30–90 days after discharge from the index hospitalization in the PP1M group compared to the OAA group (see Supplementary Material 1).

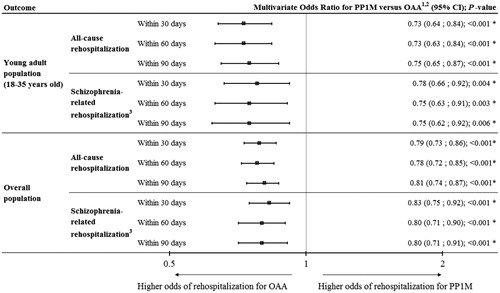

Using a multivariate model and in the young adult population, the odds of all-cause rehospitalization were lower for patients treated with PP1M during index hospitalization after 30 and 60 days (OR [95% CI] = 0.73 [0.64–0. 84], p < .001; and, 0.73 [0.63–0. 84], p < .001, respectively), as well as after 90 days of follow-up compared to patients treated with OAA during index hospitalization (OR [95% CI] = 0.75 [0.65–0.87], p < .001; ). Largely similar findings were made for schizophrenia-related hospitalizations, with lower odds (i.e. ORs ranging from 0.75–0.78) after 90 days of follow-up for patients treated with PP1M during index hospitalization compared to patients treated with OAA during index hospitalization (p < .01; ). In the overall population and still using a multivariate model, similar trends were observed: the odds of all-cause rehospitalization lower for patients treated with PP1M during index hospitalization after 30 days (OR [95% CI] = 0.79 [0.73–0.86], p < .001), 60 days (OR [95% CI] = 0.78 [0.72–0.85], p < .001), and 90 days (OR [95% CI] = 0.81 [0.74–0.87], p < .001) of follow-up compared to patients treated with OAA during index hospitalization (). Similar observations were made for schizophrenia-related rehospitalizations, with ORs ranging between 0.80–0.83 after 90 days of follow-up for patients treated with PP1M during index hospitalization compared to patients treated with OAA during index hospitalization (all p < .001; ). Results were similar in the older adult population with lower ORs for patients treated with PP1M during index hospitalization compared to patients treated with OAA during index hospitalization (> 35 years old; see Supplementary Material 2).

Figure 3. Multivariate odds ratio of rehospitalization after index hospitalization, per age group, type of rehospitalization, and time since discharge from index hospitalization. CI, confidence interval; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, version 9; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, version 10; OAA, oral atypical antipsychotics; PP1M, once-monthly paliperidone palmitate. 1The reference is OAA. The odd ratios were obtained from a generalized estimating equation model, with repeated measures per patient (as each patient may contribute more than one index hospitalization). In addition to the PP1M group variable, age, sex, marital status (single or not), race or ethnicity (white or not), geographical region, payer (Medicaid or not), teaching hospital, year of index hospitalization (before 2012 or not), psychiatrist as attending doctor, severity of illness (major/extreme or not), suicide-related diagnosis codes, length of stay, total cost, number of months from prior hospitalization, and being admitted from law or court variables were included in the model. All variables obtained before, at, or during index hospitalization. 2x-axis is on a log2 scale. 3Defined as visits with the presence of a schizophrenia diagnosis (ICD-9 codes 295.xx; ICD-10 codes F20.xx, F21.xx and F25.xx).

Discussion

In this retrospective study based on a large real-world database of hospital records, patients with schizophrenia treated with PP1M during a hospitalization had 19–27% lower odds of rehospitalization within 30–90 days after discharge relative to patients treated with OAA during a hospitalization. These results were not only observed in the overall population of adult patients with schizophrenia, but also in younger adults, suggesting that PP1M offered benefits over OAA with respect to the rate of relapse across the age spectrum and in particular among patients presumed to have been more recently diagnosed. The aforementioned odds were computed based on all index hospitalizations per patient, thereby reducing potential biases associated with the selection of only the first event. Indeed, patients receiving PP1M for the first time are likely to have prior OAA use, as per labelCitation32, while OAA-recipients are more likely to be antipsychotic-naïve. Finally, the odds of rehospitalization were similar in multivariate and univariate model, suggesting that the conclusion is robust as they held true, even in the absence of adjustments.

The results based on the adjusted model are preferable, as several baseline characteristics were different between patients treated with PP1M and OAA at index hospitalization as assessed using standardized differences (i.e. standardized difference >10%) and as expected from past studiesCitation17. The multivariate GEE model with binomial distribution adjusted for several of them, such as demographics, hospital characteristics, or healthcare costs at baseline, in addition to accounting for repeated measures per patientCitation30. Moreover, as illustrated by characteristics like the length of inpatient stay (an important predictor of rehospitalizations)Citation33, costs during the index hospitalization, transfer from law enforcement, and prior schizophrenia-related hospitalizations, patients treated with PP1M during index hospitalization had a higher disease burden at baseline in both the overall and young adult population. This observation is consistent with several previous real-world studiesCitation17,Citation25,Citation34,Citation35 and the notion that, despite compelling evidence suggesting LAIs offer benefits in patients with less severe symptoms, LAIs are mainly prescribed for difficult-to-treat and poorly adherent patients in current clinical practiceCitation33,Citation36, with limited use of LAI during the first episode of schizophreniaCitation13,Citation37.

Results from the current study challenge this notion and contribute to the growing body of evidence which supports the use of LAIs early in the course of schizophreniaCitation13,Citation20. The finding that the odds of rehospitalization for patients treated with PP1M during index hospitalization are 19–27% lower compared to patients treated with OAA during index hospitalization appear consistent with findings from Lafeuille et al.Citation17 (for PP1M). Furthermore, in a recent observational study that used Medicaid data, Pilon et al.Citation25 reported that a sub-group of younger patients initiated on PP1M had shorter cumulative length of stays for inpatient and long-term care admissions compared to OAA-initiated patients. Since the first 2–5 years following the onset of schizophrenia symptoms act as a critical determinant of long-term outcomesCitation12, additional research efforts should be focused on the long-term impact of PP1M in young adults with schizophrenia.

Although the mechanisms leading to the lower odds of rehospitalizations among patients treated with PP1M were not explored in the current retrospective study, PP1M-treated patients are typically more adherent to their medication than OAA-treated patientsCitation15,Citation16, which may lead to the lower odds of rehospitalization observed for patients treated with PP1M during index hospitalizations. Of note, non-adherence is particularly problematic in young and recently diagnosed adult patients as they tend to have poor attitudes towards antipsychotic medication, poor insight into illness, and higher rates of substance abuseCitation7,Citation8.

Limitations

The findings of this study are subject to some limitations. First, as most claims-based studies making use of large databases, results of this retrospective study can be affected by coding entry errors, missing data in the database, and residual confounding. Second, the date of the first schizophrenia diagnosis was not available in the database, hence age was used as a surrogate for time from diagnosis of schizophrenia, with the assumption that young adults were more likely to be diagnosed recently compared to older adult patients. However, patients under 18 years of age can be diagnosed with schizophreniaCitation38 and may have been included in the young adult population, despite having a relatively long disease history. Reciprocally, patients with late-onset schizophrenia aged more than 35 years old would not be included in the young adult population. Third, patients can only be traced for hospitalizations occurring at the same facility, which can lead to an under-estimation of rehospitalization rates. However, this under-estimation is expected to be equally distributed between the compared index treatment groups, such that the odds ratios should be minimally, if at all, affected.

Conclusion

In this retrospective claims-based study, the odds of rehospitalization within 30–90 days following a schizophrenia-related hospitalization were found to be lower in patients treated with PP1M during index hospitalization compared to patients treated with an OAA during index hospitalization across the age spectrum, and in particular among young adults (presumed to have been diagnosed recently with schizophrenia). Therefore, the results from this real-world study support the increasingly acknowledged view that younger adults with schizophrenia may also benefit from treatment with an LAI such as PP1M. Since the first few years following the onset of schizophrenia symptoms is a key determinant of long-term outcomes, further research is needed to evaluate the long-term direct and indirect (e.g. employment and productivity) effects of initiating PP1M treatment in younger adult patients.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Declaration of financial/other interests

DP, AMM, and PL are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has received research grants from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC., to conduct this study. At the time the study was conducted, RK was an employee of Analysis Group, Inc. TBA and ACE are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC., and Johnson & Johnson stockholders. A CMRO peer reviewer on this manuscript declares fees for oral communications in congresses from Janssen. Other CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no financial/other interests to disclose.

Previous presentation

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting, May 5–9, 2018, New York City, NY.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (62.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (85.2 KB)Acknowledgments

Assistance with preparation of tables and figures was provided by Kazi Ahmed, and medical writing assistance was provided by Samuel Rochette, both from Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has received research grants from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, to conduct this study.

References

- National Institute of Health. Schizophrenia. Available at: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/index.shtml [Last accessed June 9, 2017]. The National Institute of Mental Health Information Resource Center, Bethesda, MD; 2016

- Simpson GM. Atypical antipsychotics and the burden of disease. Am J Manag Care 2005;11(8 Suppl):S235-S41

- McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, et al. Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev 2008;30:67-76

- American Psychiatric Association. Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition. Washington, DC: APA; 2014

- Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. NEJM 2005;353:1209-23

- Haddad PM, Brain C, Scott J. Nonadherence with antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: challenges and management strategies. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2014;5:43-62

- Miller BJ, Bodenheimer C, Crittenden K. Second-generation antipsychotic discontinuation in first episode psychosis: an updated review. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 2011;9:45-53

- Quach PL, Mors O, Christensen TO, et al. Predictors of poor adherence to medication among patients with first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorder. Early Interv Psychiatry 2009;3:66-74

- Birchwood M, Todd P, Jackson C. Early intervention in psychosis. The critical period hypothesis. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998;172:53-9

- McGlashan TH, Johannessen JO. Early detection and intervention with schizophrenia: rationale. Schizophr Bull 1996;22:201-22

- Lieberman J, Jody D, Geisler S, et al. Time course and biologic correlates of treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;50:369-76

- Altamura AC, Aguglia E, Bassi M, et al. Rethinking the role of long-acting atypical antipsychotics in the community setting. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2012;27:336-49

- Heres S, Lambert M, Vauth R. Treatment of early episode in patients with schizophrenia: the role of long acting antipsychotics. Eur Psychiatry 2014;29:1409-13

- Lambert T, Olivares JM, Peuskens J, et al. Effectiveness of injectable risperidone long-acting therapy for schizophrenia: data from the US, Spain, Australia, and Belgium. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2011;10:10

- Marcus SC, Zummo J, Pettit AR, et al. Antipsychotic adherence and rehospitalization in schizophrenia patients receiving oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics following hospital discharge. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2015;21:754-68

- Lafeuille M-H, Frois C, Cloutier M, et al. Factors associated with adherence to the HEDIS quality measure in Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Am Health Drug Benefits 2016;9:399-410

- Lafeuille MH, Grittner AM, Fortier J, et al. Comparison of rehospitalization rates and associated costs among patients with schizophrenia receiving paliperidone palmitate or oral antipsychotics. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 2015;72:378-89

- Kim B, Lee SH, Choi TK, et al. Effectiveness of risperidone long-acting injection in first-episode schizophrenia: in naturalistic setting. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2008;32:1231-5

- Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2008;23:325-31

- Tiihonen J, Haukka J, Taylor M, et al. A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2011;168:603-9

- Schreiner A, Aadamsoo K, Altamura AC, et al. Paliperidone palmitate versus oral antipsychotics in recently diagnosed schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2015;169(1–3):393-9

- Emsley R, Parellada E, Bioque M, et al. Real-world data on paliperidone palmitate for the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders: a systematic review of randomized and nonrandomized studies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2018;33:15-33

- Taylor DM, Sparshatt A, O’Hagan M, et al. Effect of paliperidone palmitate on hospitalisation in a naturalistic cohort - a four-year mirror image study. Eur Psychiatry 2016;37:43-8

- Williams W, McKinney C, Martinez L, et al. Recovery outcomes of schizophrenia patients treated with paliperidone palmitate in a community setting: patient and provider perspectives on recovery. J Med Econ 2016;19:469-76

- Pilon D, Muser E, Lefebvre P, et al. Adherence, healthcare resource utilization and Medicaid spending associated with once-monthly paliperidone palmitate versus oral atypical antipsychotic treatment among adults recently diagnosed with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:207

- National Committee for Quality Assurance. Plan all-cause readmissions. Washington, DC; 2017. Available at: www.ncqa.org [Last accessed February 1, 2018]

- Thieda P, Beard S, Richter A, et al. An economic review of compliance with medication therapy in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2003;54:508-16

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Toronto: Academic; 1977

- Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat-Simul Comput 2009;38:1228-34

- Zeng LN, Rogers J, Seidensticker S, et al. Statistical models for hospital readmission prediction with application to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients. Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Bali, Indonesia, January 7–9, 2014

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT 9.2 User’s Guide, Second Edition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2009

- Invega Sustenna (R). Highlights of prescribing information. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2018. Available at: https://www.invegasustenna.com/important-product-information [Last accessed April 18, 2017]

- Agid O, Foussias G, Remington G. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: their role in relapse prevention. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2010;11:2301-17

- Baser O, Xie L, Pesa J, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs of Veterans Health Administration patients with schizophrenia treated with paliperidone palmitate long-acting injection or oral atypical antipsychotics. J Med Econ 2015;18:357-65

- Morrato EH, Parks J, Campagna EJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of injectable paliperidone palmitate versus oral atypical antipsychotics: early postmarketing evidence. J Comp Eff Res 2015;4:89-99

- Kim B, Lee SH, Yang YK, et al. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics for first-episode schizophrenia: the pros and cons. Schizophr Res Treat 2012;2012:560836

- Heres S, Reichhart T, Hamann J, et al. Psychiatrists' attitude to antipsychotic depot treatment in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry 2011;26:297-301

- Vyas NS, Gogtay N. Treatment of early onset schizophrenia: recent trends, challenges and future considerations. Front Psychiatry 2012;3:29