Abstract

Objective: To examine how medical journal editors perceive changes in transparency and credibility of industry-sponsored clinical trial publications over a 5 year period (2010 to 2015).

Methods: From July to September 2015, a survey link was emailed to journal editors identified from the Thomson Reuters registry. Editors ranked their perception of: a) change in transparency and credibility of industry-sponsored clinical trial publications; b) 8 “Publication Best Practices” and the impact of each on transparency; and c) the importance and adoption of the previously published “10 Recommendations for Closing the Credibility Gap in Reporting Industry-Sponsored Clinical Research”.

Results: Of 510 editors who opened the survey, the analysis pool comprised a total of 293 editors. The majority of respondents reported their location as the US (46%) or EU (45%) and most commonly reported editorial titles were deputy/assistant editor (36%), editor-in-chief (35%) and section editor (24%). More editors reported improved versus worsened transparency (63.5% vs. 6.1%) and credibility (53.2% vs. 10.4%). Best practices that contributed most to improved transparency were “disclosure of the study sponsor” and “registration and posting of trial results”. Respondents ranked the importance of nine recommendations as moderate or extremely important, and adoption of all recommendations was ranked minimal to moderate.

Conclusions: The 293 editors who responded perceived an improvement in the transparency and credibility of industry-sponsored publications from 2010 to 2015. Confirmation of the importance of 9/10 recommendations by the respondents was encouraging. Yet, low adoption rates suggest that additional work is required by all stakeholders to improve best practices, transparency and credibility.

Introduction

Clinical trial publications are an important source of information for healthcare practitioners and may influence prescribing decisions. In 2012, Kesselheim et al. demonstrated that the extent to which internists are prepared to act on findings in the medical literature is influenced by how credible they believe the publications are; National Institutes of Health (NIH)-sponsored articles were believed to be more trustworthy than pharmaceutical-industry-sponsored publicationsCitation1. This relative lack of credibility regarding industry-sponsored publications may result in physicians discounting the latest trial data that could benefit patients.

The pharmaceutical industry’s credibility has been damaged by reports of selective or biased disclosure of research results, lack of adherence to authorship guidelines and commercial involvement in publicationsCitation2–4. One factor contributing to credibility is transparency, which here refers to the extent that industry discloses the clinical trials conducted, subsequent results, and relationships between the authors, sponsors and medical writers, including potential conflicts of interest (both financial and nonfinancial). To improve transparency and credibility in publications, many stakeholders have improved or clarified their disclosure standards. In 2004, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) required study registration as a prerequisite for publishingCitation5. Subsequently, the Food and Drug Administration mandated study registration and posting of basic results on ClinicalTrials.govCitation6. In 2010, the pharmaceutical associations encouraged their members to submit manuscripts for all phase 3 clinical trialsCitation7. Many pharmaceutical companies have since implemented policies and guidance to promote transparency and credibility: adopting ICMJE authorship criteria; disclosing study sponsor and medical writing support; and providing authors with greater access to trial dataCitation8–16. In 2008, five pharmaceutical companies and the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP) established Medical Publishing Insights & Practices (MPIP), a collaboration to elevate trust, transparency and integrity in publishing industry-sponsored studies. Through a multidisciplinary collaboration, MPIP partnered with journal editors to generate 10 recommendations for closing the credibility gap in reporting industry-sponsored clinical research ()Citation17.

Table 1. Top 10 recommendations for closing the credibility gap in reporting industry-sponsored clinical research.

Despite these initiatives, transparency policies among pharmaceutical companies regarding clinical research methods and results vary widely as evidenced by the assessment of Goldacre et al.Citation18. In 2015, MPIP set out to survey medical journal editors to measure whether the transparency and credibility of industry-sponsored clinical research has improved. MPIP chose medical journal editors because they are responsible for the “validity, objectivity, utility and integrity” of the manuscripts their journals publishCitation19 and have expressed concerns about the integrity of industry-sponsored research in multiple forums, including roundtable meetings, position statements and editorialsCitation5,Citation17,Citation20,Citation21. The survey was designed to evaluate: (1) whether there has been a change in journal editors’ perceptions regarding the transparency and credibility of industry-sponsored publications from 2010 to 2015 and to assess publication best practices (referred to as “best practices”) that may have contributed to the change; and (2) the perception of the importance and the degree of adoption by industry of the MPIP 10 recommendations. Five years was deemed a sufficient timeframe for the embedding of publication guidelines and company policies.

Methods

Survey population identification

English language medical journals were identified using the Thomson Reuters Journal Citation Report 2013. The top 40 journals in each of 36 medical categories were selected if they published clinical trial results and had an Impact Factor ≥1; a total of 885 different journals were identified (Supplementary Appendix 1). We sought responses from experienced editors who were primarily involved with detailed review of manuscript content and were in the field long enough to have observed any change that may have occurred, rather than editors whose tasks were primarily administrative or operational. Editors were then identified from the list of qualified journals. After reviewing each journal’s editorial staff as listed on the masthead, the first 10 editors were chosen as they tended to be listed in order of seniority. Those who later reported in the survey that they had any of the following titles: editor, editor-in-chief, deputy editor, associate editor, senior editor, section editor, assistant editor or similar were included, whereas managing editors, editorial board members and consulting editors were excluded. To ensure that each editor received only one survey, duplicates of a name were removed.

Survey design

A web-based, English language survey (Supplementary Appendix 2) was developed by MPIP and documented according to the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) (Supplementary Appendix 3)Citation22. The survey questions were reviewed with two journal editors who had previously participated in MPIP activities and offered to evaluate the survey for ease of comprehension and applicability. The survey instrument contained 23 questions, including two screening questions to ensure that respondents were editors of journals that published clinical trials. If their title was not included in the answer choices to the screening question “Which title best describes your current editorial responsibilities?” editors could select “Other, please specify”. These “other” responses were manually reviewed by the authors (B.M., L.A.M., L.F.) and consultant (D.M.) to determine whether the editor’s responsibilities met the inclusion criterion (Supplemental Table S1).

The primary survey endpoint questions asked the respondents to select the response that best describes the degree of change they had observed in: (1) the transparency; and (2) the credibility of industry-sponsored clinical trial publications over the past five years. Responses were scored on a 5 point Likert scale (substantially worse, slightly worse, no change, slightly better, substantially better). When the Likert scale was used, the “cannot assess” option was available to editors who felt they did not have enough experience or information to provide an accurate assessment.

To isolate distinct actions that may have impacted transparency, MPIP identified eight best practices mandated or recommended by journal editors, regulatory agencies and industry organizations that have been implemented by pharmaceutical companiesCitation6,Citation23,Citation24. Respondents who indicated an improvement in transparency were asked to rank the degree of impact each best practice had on improving transparency. The survey included an open-ended response option “other” to capture practices outside the eight listed. To understand which best practices may require additional attention by industry, all respondents were asked to rank the degree of unmet need for each of the eight best practices or “other” responses. The results were summarized for each subgroup.

The editors were also asked to evaluate the level of importance of each of the 10 recommendations and how well industry had adopted each. Editors who ranked a recommendation as moderately/extremely important yet the adoption as minimal/none were asked to provide a rationale for their responses.

For the survey to be considered “submitted”, all questions had to be answered and the submit button selected. Respondents could not return to previously answered questions.

Survey implementation

The survey was programmed and hosted by Infocorp Ltd. (London, UK). The unsolicited survey invitations were sent in two phases, beginning 17 July and completing 26 September 2015, to each editor’s email address with a unique identifier and link to the survey website. During that time period, reminder emails were sent to editors who had not begun or not yet completed the survey (Supplemental Figure S1 and Supplemental Table S2). Respondents were not compensated for their participation.

Data management and analysis

All responses were anonymized; data are analyzed using SPSS software, version 21. Results were reviewed and the interpretation confirmed by an independent, academic statistician. Descriptive statistics (n, percentage, mean ± standard deviation) were calculated; responses of “cannot assess” were not assigned a Likert score and thus were not included in the calculation of mean values, but were included in the overall percentage. Open-ended responses were reviewed by the authors for common themes.

As a post hoc assessment to evaluate potential bias, we:

Compared actual responders with nonresponders on the basis of their editorial title using a chi-square test.

Compared the primary endpoint results among editors who responded after 0 or 1 email reminders (early responders), or after 2–5 reminders (late responders) by both analysis of variance and chi-square testing. The late responders are considered imperfect surrogates for nonresponders.

Assessed the relationship between early vs. late response and number of years of experience (≤5 vs. >5), and geographic location (USA and Canada vs. rest of world) using chi-square tests.

Results

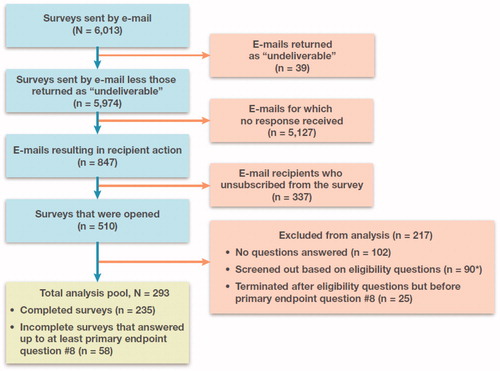

Of the 510 editors who opened the survey (among 6013 emails sent), the analysis pool comprised a total of 293 editors who met the eligibility and screening criteria; 235 editors completed and submitted the survey and an additional 58 answered up to at least the primary endpoint question on transparency (). Survey respondents were self-described as deputy or assistant editors (36%), editors-in-chief (35%) or section editors (24%). “Other” was chosen by 5% of the respondents, including editors who described themselves as holding positions at more than one journal, or having more than one title (e.g. section editor and deputy editor). Seventy-four percent of respondents stated they were editors of a disease-specific or specialty journal. The majority of respondents (91%) were editors based in North America (46%) or Europe (45%) (Supplemental Figure S2). Sixty-four percent of respondents reported ≥5 years of editorial experience (mean, 8.5 years; range, 1 to 40) (Supplemental Figure S3).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of survey recruitment and responses. Blue boxes show the path from the initial invitations (N = 6013) to the pool of completed and submitted surveys (n = 235). Pink boxes show the surveys that were undeliverable, not responded to, unsubscribed or screened out. The primary analysis pool (green box) was composed of the 235 remaining completed and submitted surveys plus the 58 incomplete surveys that contained a response for at least the first primary endpoint question on transparency. *Of the 90 surveys screened out, 82 were excluded automatically based on responses to eligibility questions, and 8 were manually screened out based on open-ended responses to eligibility question 1 that suggested those individuals’ primary responsibilities were not editorial in nature (6 from the submitted surveys and 2 from the incomplete surveys).

Transparency and credibility

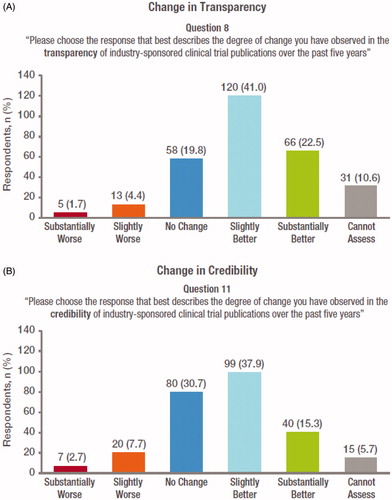

An improvement (slightly/substantially better) in transparency of industry-sponsored clinical trial publications was reported by 63.5% of respondents. A decrease in transparency (slightly/substantially worse) was reported by 6.1%; no change by 19.8% and “cannot assess” by 10.6% ().

Figure 2. Journal editor perceptions of changes in (A) transparency and (B) credibility in industry-sponsored clinical trial publications from 2010 to 2015. Respondents were asked to rank changes in transparency and credibility on a 5 point Likert scale from “substantially worse” to “substantially better”. The number and proportion of responders who were unable to make an assessment (“cannot assess”) is also shown.

An improvement (slightly/substantially better) in credibility of industry-sponsored clinical trial publications was reported by 53.2% of respondents. A decrease in credibility (slightly/substantially worse) was reported by 10.4%; no change by 30.7% and “cannot assess” by 5.7% ().

A sensitivity analysis of all actual responders versus all nonresponders (n = 5964) revealed that responders tended to have titles that were more senior than nonresponders (two-sided p value <.001) (Supplemental Table S3). The analysis comparing the primary endpoints of transparency and credibility by number of email reminders (0 or 1 vs. 2–5), revealed that the two groups did not differ significantly in their responses (p >.1) (Supplemental Table S4). This was independent of the testing method (analysis of variance or chi-square). Similar reminder email analyses were also performed to determine whether years of experience (≤5 vs. >5) or geographic location (USA and Canada vs. rest of world) was associated with responder status. At the 5% significance level, there were no statistically significant relationships between reminder level and experience or country (Supplemental Table S5 and Supplemental Table S6).

Publication best practices

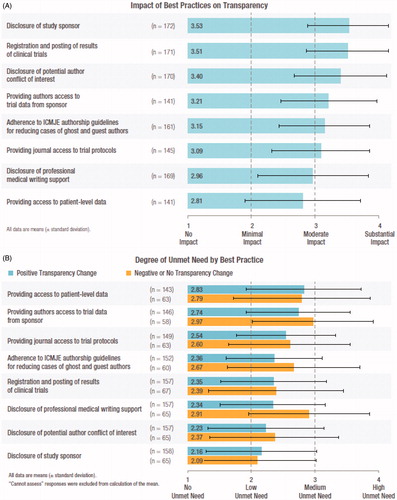

Respondents who indicated an improvement in transparency reported that six of the eight best practices listed had at least moderate impact on that improvement. The best practices “disclosure of study sponsor” and “registration and posting of results of clinical trials” were reported as having the greatest impact (). The remaining two best practices, “disclosure of medical professional writing support” and “providing access to patient-level data”, were reported to have had a minimal to moderate impact. “Cannot assess” was selected by <10% of the respondents for five of the eight best practices. A higher proportion of respondents could not assess the impact of the remaining three best practices: “providing access to patient-level data” (19%), “providing authors access to trial data from the sponsor” (19%) and “providing journal access to trial protocols” (17%) (data not shown). All respondents (regardless of perception of improvement in transparency) reported a low to medium unmet need for all eight best practices (). Editors were also invited to provide open-ended responses if they wished.

Figure 3. (A) Impact of best practices on transparency, and (B) degree of unmet need by best practice. In Panel A, respondents who reported a positive change in transparency were asked to rank each of eight best practices on a 4 point Likert scale from “no impact” to “substantial impact”; mean scores (± standard deviation) are shown. In Panel B, respondents were asked to assess the remaining unmet need associated with each best practice, ranked on a 4 point Likert scale from “no unmet need” to “high unmet need”; mean scores (± standard deviation) are shown. Responses of “cannot assess” were not assigned a score and thus were not included in calculations of mean and standard deviation.

Editors who did not find the best practice that contributed to improved transparency listed in the answer choices were able to specify others (e.g. reporting guidelines for authors, a contributorship model for authorship and the use of neutral language when discussing study data). A complete list of de-identified open-ended responses is included as a Supplementary appendix (Supplementary Appendix 4).

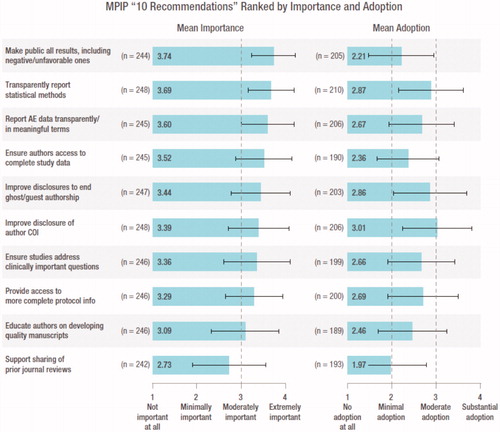

MPIP 10 recommendations

The respondents ranked the importance of 9 of the 10 recommendations as moderately to extremely important and their adoption as minimal to moderate (). “Support the sharing of prior reviews from other journals” was the only recommendation ranked as having minimal importance and adoption. The recommendation “make public all results including negative and unfavorable ones, in a timely fashion, while avoiding redundancy” was ranked as the most important but had one of the lowest adoption scores. A small percentage of respondents reported “cannot assess” to the importance of the 10 recommendations (2% to 5%). However, industry’s adoption of the 10 recommendations was more challenging for respondents to assess (15% to 24% could not assess).

Figure 4. MPIP “10 recommendations” ranked by importance and adoption. Respondents were asked to rank the importance and level of adoption of each of the 10 recommendations on a 4 point Likert scale from “not important/no adoption” to “extremely important/substantial adoption”; mean scores (± standard deviation) are shown. Responses of “cannot assess” were not assigned a score and thus were not included in calculations of mean and standard deviation. All data are mean (± standard deviation). “Cannot assess” has been excluded from the calculation of the average. AE, adverse event; COI, conflict of interest.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first survey to assess medical journal editors’ perceptions on the transparency and credibility of industry-sponsored clinical trial publicationsCitation25–28. Here, 63.5% of the 293 responding editors reported an increase in transparency, and 53.2% reported an increase in credibility in clinical trial publications over the 5 years from 2010 to 2015.

The greater increase (10.3%) in transparency versus credibility may reflect broad interpretation of the term “credibility”, which has been defined as “believability, trust, reliability, accuracy, fairness, objectivity, and dozens of other concepts and combinations thereof”Citation29. The concept central to credibility is believabilityCitation30. Therefore, although transparency can be linked to specific, verifiable actions (e.g. disclosure of sponsor; financial and editorial support; disclosure of study results), we believe that credibility may be more subjective and take time to be earned or builtCitation30.

Publication best practices

Each of the eight best practices assessed were found to contribute to the increase in transparency. The two most impactful were “disclosure of study sponsor” and “registration and posting of results of clinical trials”. We believe that these two best practices were ranked highest because they have been broadly adopted by industry and journals, they are highly visible and they have been followed by external partiesCitation31–33. Routine disclosure of the study sponsor in published manuscripts has been facilitated by ICMJE and Good Publication Practice (GPP3) and reinforced by journal submission guidelinesCitation23,Citation24. Notably, US and European legislation and ICMJE requirements have made the registration and posting of clinical trial results mandatoryCitation6,Citation34.

“Disclosure of potential author conflict of interest” was also ranked highly for impacting transparency. Conflict of interest in medical research has been widely discussed in the peer-reviewed literature and the popular pressCitation35–38. As a result, authors should be aware of their obligation to accurately report all relevant financial and personal relationships that could potentially bias their work or undermine the transparency and credibility of the researchCitation23,Citation38.

The least impactful best practice for transparency was “providing access to patient-level data”. This was not unexpected given that, at the time of the survey, there was a lack of consensus among the many stakeholders on various aspects of data sharing, including timing of data sharing, protection of intellectual property and confidentiality of trial participants’ data. Since that time, the ICMJE recommendation that requires a data sharing statement in manuscripts reporting trial results in ICMJE journals (effective 1 July 2018) has clarified the landscape regarding plans for the availability of clinical dataCitation39. Prior to the ICMJE statement, many pharmaceutical companies had already implemented policies to allow access to patient-level data. Data is made available directly by the sponsoring company, through universities or via an industry consortiumCitation40–44.

MPIP 10 recommendations

The survey confirmed the importance of 9 of the 10 recommendations ()Citation17. Respondents viewed “support the sharing of prior reviews from other journals” as only minimally important for improving credibility and were of mixed opinions on whether it would be helpful.

Despite the significant attention several of the 10 recommendations have received from stakeholders including authors, editors, research sponsors and regulatory authorities during the time period of our survey, the perception is that adoption has clearly been less than optimal. This may reflect a lack of: consistent implementation of recommendations across all companies, standard processes for implementing them (e.g. “provide access to more complete protocol information”), consensus regarding the importance of any specific recommendation (e.g. “sharing of prior reviews”) or visibility of industry progress by editors. However, this may soon be remediated in part by the requirement for sponsors of clinical trials to submit a complete protocol to ClinicalTrials.govCitation45.

The fact that some recommendations relate to established processes and procedures (e.g. “understanding and disclosure of authors’ potential conflicts of interest”) whereas others rely on sponsor-level implementation (e.g. “ensure authors access to complete study data”) may have contributed to variability in adoption scores. Furthermore, progress being made by individual sponsors in these areas is not always widely communicated across industry.

Progress and future plans

Since 2008, MPIP has worked with editors to support best practices and the behaviors underlying the 10 recommendations by developing practical tools and guidance documents for authors and other stakeholdersCitation46–48. Further progress in transparency and credibility will require the sustained efforts of numerous stakeholders. Some campaigns are underway to improve the sharing of trial protocolsCitation49,Citation50.

The editors viewed “Make public all results including negative or unfavorable ones” as most important but least adopted. Editors in our survey indicated the publishing of negative results was uncommon or they were unaware that it was occurring. Both the poor adoption score and quotes, like “Negative results continue to fail to be published” and “This is a failure of both authors and journals in my view” support this perception. This will be a critical area of focus for MPIP, because without progress in this area, significant improvements in credibility are unlikely to be achieved. Ongoing efforts by journals, industry, associations and others encourage greater reporting transparencyCitation4,Citation24,Citation51. Several pharmaceutical companies have incorporated the requirement to publish all study results independent of study outcome into their policiesCitation10–16,Citation40,Citation41. However, significant hurdles remain. Although journals are more receptive to publishing neutral or negative results, these are typically perceived as less newsworthy than positive outcomes and can require additional effort to achieve publicationCitation52. Industry and journal editors need to assist with the publishing of these studies in the scientific literature. The authors encourage not only publications, but alternate formats for making data publicly available, such as registries (e.g. clinicaltrials.gov or EudraCT), but also the AllTrials initiativeCitation4.

Clearly more effective communication is essential. In addition to publishing evidence of progress, we must share the right information with the right audiences. Therefore, MPIP will continue to communicate best practices for adverse event reportingCitation48, proper disclosures of financial support, authorship criteria and early data sharing with authors, etc. Our members are working within their own research and medical divisions to further embed best practices and publish evidence of progress where it has been achievedCitation52,Citation53.

Strengths and limitations

A limitation of this study is the low percentage of responders. Lack of familiarity with MPIP may have contributed to the low response rate because only 17% of editors noted in their survey responses that they were familiar with MPIP. Nonresponders may have deleted or ignored the emails from an organization unknown to them. Other potential limitations include fatigue from receiving multiple survey requests, disinterest, recipients’ lack of expertise in the subject matter or the length of the survey (23 questions). Given the limitations of the software used, we cannot determine the proportion of emails that were delivered versus those diverted to spam folders.

A strength of our study is that, unlike many surveys, we offered no financial incentive. The offer of financial reward for participation has the potential to bias the responder population. Another strength of the survey is that, in addition to the responses from 293 editors to our structured questions, we gained insights on editor perspectives through the open-ended questions. The comments were diverse yet informative and covered the range of topics included in the 10 recommendations. Several editors remarked that “The quality of submissions remains variable with no consistent improvement over the last five years”. However, other respondents felt that it was not industry’s responsibility to educate authors on how to generate quality manuscripts and meet journal expectations (Supplementary Appendix 4).

It must be noted that, due to the large number of editors who did not respond to the survey email, these results cannot be generalized to all editors; rather they represent only the views of those who responded. Nevertheless, the absolute number of respondents was comparable to or greater than two other published surveys of journal editorsCitation25,Citation46. The analysis for nonresponder bias revealed that responders had more senior editorial titles than nonresponders, which is consistent with our aim to survey more experienced editors. The additional nonresponder analysis using early vs. late email response revealed no significant findings for either of the primary endpoints. The analysis for response versus nonresponse based on seniority revealed that responders had more senior titles than nonresponders.

This survey was intended to measure change in perceptions of transparency or credibility of industry-sponsored clinical trial publications from 2010 to 2015. We did not ask the editors to assign a current level of transparency and credibility to industry publications. This limitation is mitigated by the fact that there is no mutually agreed upon measure for transparency or credibility. Each respondent used his or her own standard to compare change over time, thus accounting for any heterogeneity in editors’ baseline assessment of transparency and credibility.

In addition, we only evaluated changes in journal editor perceptions of industry-sponsored clinical trial publications; it is not possible to assess from our data whether perceptions would differ if publicly sponsored clinical trial publications were considered. Independent third parties have reported objective metrics on this issue that are more likely to be widely accepted by the publicCitation18,Citation54. Gopal et al. assessed prospective registration rates of trials published in high-impact specialty journals from 2010 to 2015, and found that trials with industry funding had higher rates of registration compared to those which did notCitation31. Although these results are promising, there is still room for improvementCitation33. Miller et al. have developed “Good Pharma Scorecards” designed to evaluate the transparency and compliance of clinical data reporting by large pharmaceutical companiesCitation32,Citation33. Their scorecards suggest that some measures of clinical trial transparency, including public availability of data from trials in patients, increased from 2012 to 2014, or during the time period covered by our survey.

Admittedly, due to the time needed to collect and analyze data, as well as the challenge in publishing data on editors’ perceptions of transparency and credibility, this survey may not fully represent the current landscape. However, the improvement in the editors’ perception of transparency and credibility of industry trials seems to be consistent with the positive change in transparency compliance observed by Miller et al.Citation33, and we are hopeful that this trend will continue.

The robustness of the primary endpoint analysis (transparency and credibility) is a major strength of this study. The overall results from the analysis population were unchanged when the results were stratified by years of editorial experience (Supplemental Figure S4) and by early versus late responder status (Supplemental Table S4).

Conclusions

The journal editors surveyed indicated an improvement in their perception of transparency and credibility of industry-sponsored clinical trial publications from 2010 to 2015, while highlighting persistent unmet needs in best practice adoption. Further education regarding the impact of transparency on patient care, scientific advancement and credibility, combined with embedding of best practices and communication of progress achieved, are needed to close this gap. To support this effort, we have launched MPIP Transparency Matters, a global educational platform and call to actionCitation55. Sustained commitment and shared responsibility are required to achieve desired levels of both transparency and credibility.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Financial support for the manuscript was provided by MPIP, which is currently funded by Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Research & Development LLC, Merck, Pfizer and Takeda. The authors of this manuscript participated in the research on behalf of MPIP, rather than their employers. The authors are responsible for the manuscript content. The sponsor companies had no direct involvement in the conduct of the research and/or preparation of the article.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors have disclosed that they are employed by MPIP sponsor companies. L.A.M. and T.A.Z. have disclosed that they are employees and shareholders of Pfizer. L.F. has disclosed that she is a shareholder of Pfizer and was an employee of Pfizer when the research was conducted and the manuscript drafted. L.A.M. and B.M. have disclosed that they are authors of “Ten recommendations for closing the credibility gap in reporting industry-sponsored clinical research: a joint journal and pharmaceutical industry perspective”. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(5):424–429. B.D.C. and B.M. have disclosed that they are employees and shareholders of GlaxoSmithKline. B.M. has disclosed that she serves as chair of MPIP.

CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Index of Supplemental Materials

Download MS Word (13.7 KB)Appendix 1

Download PDF (238.7 KB)Appendix 2

Download PDF (194.5 KB)Appendix 3

Download PDF (81.9 KB)Appendix 4

Download PDF (259.4 KB)Supplemental Figure S1

Download PDF (75.4 KB)Supplemental Figure S2

Download PDF (69.4 KB)Supplemental Figure S3

Download PDF (122.3 KB)Supplemental Figure S4

Download PDF (138.9 KB)Supplemental Table S1

Download MS Word (18 KB)Supplemental Table S2

Download PDF (255.6 KB)Supplemental Table S3

Download MS Word (34.5 KB)Supplemental Table S4

Download MS Word (43.3 KB)Supplemental Table S5

Download MS Word (35.1 KB)Supplemental Table S6

Download MS Word (34.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank all of the journal editors who participated in this survey; Doug Martin, Navigant Consulting Inc., Boston, MA, for data collection and analysis; and Professor Oded Netzer, Columbia Business School, New York, NY, for assistance with the survey design and data analysis and interpretation. We thank Teresa Peña PhD, at the time of writing from Bristol-Meyers Squibb and currently of Healthcare Consultancy Group, Beachwood, Ohio, for her contributions to questionnaire design and analysis of the open-ended responses. We thank William Sinkins PhD and James R. Cozzarin ELS MWC of Healthcare Consultancy Group, Beachwood, Ohio, for medical writing and editorial support, which was funded by MPIP.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Kesselheim AS, Robertson CT, Myers JA, et al. A randomized study of how physicians interpret research funding disclosures. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):1119–1127.

- McGauran N, Wieseler B, Kreis J, et al. Reporting bias in medical research – a narrative review. Trials. 2010;11:37.

- Chalmers I, Glasziou P, Godlee F. All trials must be registered and the results published. BMJ. 2013;346:f105.

- Alltrials.net. All trials registered. All results reported [Internet] [cited 2016 Nov 8]. Available from: http://www.alltrials.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/What-does-all-trials-registered-and-reported-mean.pdf

- De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, et al. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(12):1250–1251.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2016 November 8]. Available from: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-110publ85/pdf/PLAW-110publ85.pdf

- International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations. Joint Position on the Publication of Clinical Trial Results in the Scientific Literature [Internet]. 2010 [cited 8 Nov 2016]. Available from: http://www.efpia.eu/uploads/Modules/Documents/20100610_joint_position_publication_10jun2010.pdf

- Pfizer. Public Disclosure of Pfizer Clinical Study Data and Authorship [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2016 Nov 9]. Available from: http://www.pfizer.com/research/research_clinical_trials/registration_disclosure_authorship

- GlaxoSmithKline. Public Disclosure of Clinical Research [Internet]. 2014 [cited 9 Nov 2016]. Available from: https://www.gsk.com/en-gb/research/our-approach/sharing-our-research/

- Janssen. Clinical Data Transparency [Internet] [cited 2017 Apr 24]. Available from: http://www.janssen.com/us/clinical-data-transparency

- Amgen. Clinical Trial Transparency, Data Sharing and Disclosure Practices [Internet] [cited 2017 Apr 24]. Available from: http://www.amgen.com/about/how-we-operate/policies-practices-and-disclosures/ethical-research/clinical-data-transparency-practices/

- AstraZeneca. AstraZeneca Clinical Trials Website [Internet] [cited 2017 Apr 24]. Available from: https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Search

- Biogen. Clinical Trial Transparency and Data Sharing [Internet] [cited 2017 Apr 24]. Available from: http://clinicalresearch.biogen.com/

- Bristol-Meyers Squibb. Disclosure Commitment [Internet] [cited 2017 Apr 24]. Available from: https://www.bms.com/researchers-and-partners/clinical-trials-and-research/disclosure-commitment.html

- Merck. Policies and Perspectives [Internet] [cited 2017 Apr 24]. Available from: http://www.merck.com/clinical-trials/policies-perspectives.html

- Takeda. Takeda Clinical Trials [Internet] [cited 2017 Apr 24]. Available from: https://www.takedaclinicaltrials.com/

- Mansi BA, Clark J, David FS, et al. Ten recommendations for closing the credibility gap in reporting industry-sponsored clinical research: a joint journal and pharmaceutical industry perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(5):424–429.

- Goldacre B, Lane S, Mahtani KR, et al. Pharmaceutical companies’ policies on access to trial data, results, and methods: audit study. BMJ. 2017;358:j3334.

- Albert DM, Liesegang TJ, Schachat AP. Meeting our ethical obligations in medical publishing: responsibilities of editors, authors, and readers of peer-reviewed journals. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(5):684–686.

- DeAngelis CD, Fontanarosa PB. Impugning the integrity of medical science: the adverse effects of industry influence. JAMA. 2008;299(15):1833–1835.

- Angell M. Industry-sponsored clinical research: a broken system. JAMA. 2008;300(9):1069–1071.

- Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34.

- ICMJE. Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals [Internet] [cited 2018 Dec 21]. Available from: http://www.icmje.org/icmje-recommendations.pdf

- Battisti WP, Wager E, Baltzer L, et al. Good publication practice for communicating company-sponsored medical research: GPP3. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):461–464.

- Wager E, Fiack S, Graf C, et al. Science journal editors’ views on publication ethics: results of an international survey. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(6):348–353.

- Hopewell S, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. Endorsement of the CONSORT statement by high impact factor medical journals: a survey of journal editors and journal ‘Instructions to Authors’. Trials. 2008;9:20.

- Fuller T, Pearson M, Peters J, et al. What affects authors’ and editors’ use of reporting guidelines? Findings from an online survey and qualitative interviews. PloS One. 2015;10(4):e0121585.

- Hooft L, Korevaar DA, Molenaar N, et al. Endorsement of ICMJE’s Clinical Trial Registration Policy: a survey among journal editors. Netherlands J Med. 2014;72(7):349–355.

- Self CC. Credibility. In: Salwen MB, Stacks DW, editors. An integrated approach to communication theory and Research. Mahway (IL).: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. p. 421–441.

- Hilligoss B, Rieh SY. Developing a unifying framework of credibility assessment: construct, heuristics, and interaction in context. Inf Proc Manage. 2008;44:1467–1484.

- Gopal AD, Wallach JD, Aminawung JA, et al. Adherence to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors’ (ICMJE) prospective registration policy and implications for outcome integrity: a cross-sectional analysis of trials published in high-impact specialty society journals. Trials. 2018;19(1):448.

- Miller JE, Korn D, Ross JS. Clinical trial registration, reporting, publication and FDAAA compliance: a cross-sectional analysis and ranking of new drugs approved by the FDA in 2012. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e009758.

- Miller JE, Wilenzick M, Ritcey N, et al. Measuring clinical trial transparency: an empirical analysis of newly approved drugs and large pharmaceutical companies. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e017917.

- European Medicines Agency. European Medicines Agency policy on publication of clinical data for medicinal products for human use [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2017 Mar 13]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2014/10/WC500174796.pdf

- Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289(4):454–465.

- Dunn AG, Coiera E, Mandl KD, et al. Conflict of interest disclosure in biomedical research: a review of current practices, biases, and the role of public registries in improving transparency. Res Integ Peer Rev. 2016;1:1–8.

- Cannon MF. How To Minimize Conflicts of Interest in Medical Research [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelcannon/2016/04/04/how-to-minimize-conflicts-of-interest-in-medical-research/#3d527515398d

- Ornstein C, Thomas K. Top Cancer Researcher Fails to Disclose Corporate Financial Ties in Major Research Journals: ProPublica [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.propublica.org/article/doctor-jose-baselga-cancer-researcher-corporate-financial-ties

- Taichman DB, Sahni P, Pinborg A, et al. Data sharing statements for clinical trials: a requirement of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(1):63–65.

- GlaxoSmithKline. Clinical Study Register [Internet] [cited 14 Mar 2017]. Available from: http://www.gsk.com/en-gb/research/sharing-our-research/clinical-study-register/

- Pfizer. Trial Data & Results [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 14]. Available from: http://www.pfizer.com/research/clinical_trials/trial_data_and_results

- CSDR. Clinical Study Data Request [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 14]. Available from: https://clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Default.aspx

- Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Yale University. The Yoda Project [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 14]. Available from: http://yoda.yale.edu/

- Duke Clinical Research Institute. Open Science [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 14]. Available from: http://www.dcri.org/insights/open-science/

- Clinicaltrials.gov [Internet] [cited 2018 Dec 11]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/manage-recs/fdaaa

- Marusic A, Hren D, Mansi B, et al. Five-step authorship framework to improve transparency in disclosing contributors to industry-sponsored clinical trial publications. BMC Med. 2014;12:197.

- Chipperfield L, Citrome L, Clark J, et al. Authors’ Submission Toolkit: a practical guide to getting your research published. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(8):1967–1982.

- Lineberry N, Berlin JA, Mansi B, et al. Recommendations to improve adverse event reporting in clinical trial publications: a joint pharmaceutical industry/journal editor perspective. BMJ. 2016;355:i5078.

- European Medicines Agency. Trial protocols: modalities and timing of posting [Internet] [cited 2017 Apr 24]. Available from: https://eudract.ema.europa.eu/docs/guidance/Trial%20protocols_Modalities%20and%20timing%20of%20posting.pdf

- Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical Trials Registration and Results Information Submission; Final Rule. 42 CFR Part 11 [Internet]. Effective 2017 Jan 18 [cited 2017 Jun 6]. Available from: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/09/21/2016-22129/clinical-trials-registration-and-results-information-submission

- International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations. Consensus framework for ethical collaboration [Internet] [cited 2017 Apr 24]. Available from: http://www.ifpma.org/subtopics/consensus-framework-for-ethical-collaboration/?parentid=264

- Evoniuk G, Mansi B, DeCastro B, et al. Impact of study outcome on submission and acceptance metrics for peer reviewed medical journals: six year retrospective review of all completed GlaxoSmithKline human drug research studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1726.

- Mooney LA, Fay L. Cross-sectional study of Pfizer-sponsored clinical trials: assessment of time to publication and publication history. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e012362.

- DeVito NJ, French L, Goldacre B. Noncommercial funders’ policies on trial registration, access to summary results, and individual patient data availability. JAMA. 2018;319(16):1721–1723.

- Medical Publishing Insights & Practices. MPIP Transparency Matters [Internet] [cited 2017 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.mpip-initiative.org/transparencymatters/index.html