Abstract

Objective: To estimate the cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula (eHCF) plus the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (eHCF plus LGG; Nutramigen* LGG®) compared to an eHCF alone as first-line dietary management for Immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) in the UK.

Methods: Decision modelling was undertaken to estimate the probability of IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergic infants being symptom free (i.e. not experiencing urticaria, eczema, asthma or rhinoconjunctivitis) and developing tolerance to cow’s milk by 5 years. The model also estimated the cost (at 2016/2017 prices) of healthcare resource use funded by the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) over 5 years after starting a formula, as well as the relative cost-effectiveness of the two dietary formulae.

Results: At 5 years after the start of a formula the probability of being symptom free was estimated to be 0.97 and 0.76 among infants who were originally fed eHCF plus LGG and an eHCF alone, respectively. This encompassed the probability of children being asthma free at 5 years after the start of treatment, which was 0.99 and 0.91 in the eHCF plus LGG and eHCF alone groups, respectively. Additionally, the probability of acquiring tolerance to cow’s milk was estimated to be 0.94 and 0.66 among infants who were originally fed eHCF plus LGG and an eHCF alone, respectively. The estimated total healthcare cost over 5 years of initially feeding infants with eHCF plus LGG was less than that of feeding infants with an eHCF alone (£4229 versus £5136 per patient).

Conclusions: First-line management of newly diagnosed infants with IgE-mediated CMPA with eHCF plus LGG instead of an eHCF alone improves outcome, releases healthcare resources for alternative use, reduces the NHS cost of patient management and thereby affords a cost-effective dietetic strategy to the NHS.

Introduction

Cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) is one of the most common food allergies in early childhood, with an estimated annual prevalence of 2% to 3%Citation1. Guidelines for managing infants with CMPA recommend the use of substitutive hypoallergenic formulaeCitation2,Citation3. Two studies comparing different formulae found that feeding cow’s milk allergic children with an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula (eHCF) supplemented with the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) (Nutramigen* LGG®; eHCF plus LGG) resulted in higher acquisition of tolerance to cow’s milk protein compared with those fed an eHCF without LGG and other formulaeCitation4,Citation5. Additionally, feeding eHCF plus LGG first line to both immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated and non-IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergic infants, compared to feeding with an eHCF alone or an amino acid formula, was found to be cost-effective in ItalyCitation6, SpainCitation7, PolandCitation8 and the USCitation9,Citation10.

Food-related reactions are associated with a broad range of signs and symptoms that may involve several body systems, including the skin, gastrointestinal and respiratory tractsCitation11. Results from a recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) found that the relative risk for the occurrence of at least one allergic manifestation (urticaria, eczema, asthma or rhinoconjunctivitis) was reduced by 49% over 3 years among IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergic children who were fed eHCF plus LGG compared with those fed an eHCF aloneCitation12. The comparative health economic impact of these two formulae in reducing allergic manifestations in cow’s milk allergic infants is unknown. Consequently, the objective of the current study was to use data from the aforementioned RCTCitation12 to estimate the medium- to long-term cost-effectiveness of feeding IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergic infants with eHCF plus LGG, compared with an eHCF alone, from the perspective of the UK’s National Health Service (NHS).

Methods

Economic model

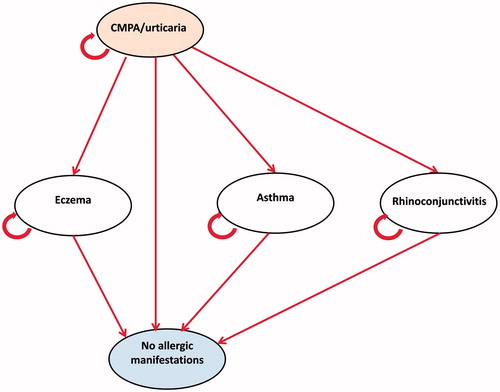

A Markov model was constructed to simulate the management of infants with IgE-mediated CMPA who are managed first line with eHCF plus LGG or an eHCF alone over a period of 5 years (). The model structure and health states were based on the aforementioned RCTCitation12. The Markov model comprised the following five health states: initial presentation of the symptoms of CMPA/urticaria; eczema; asthma; rhinoconjunctivitis and symptom free (no allergic manifestations). Within the model patients can also acquire tolerance to cow’s milk at any time.

Patients enter the model at the time of initial presentation of the symptoms of CMPA. Patients either remain in this health state or move to one of the other health states. Patients transition in the model every year. The model was populated with: (1) estimates of clinical outcomes reported in the aforementioned RCTCitation12 and (2) estimates of healthcare resource use derived from interviews with four general practitioners (GPs) in the UK with experience of managing CMPA.

Model inputs – clinical outcomes

The RCTCitation12 was performed between October 2008 and December 2014. Otherwise healthy infants (n = 220; median age at recruitment of 5.0 months; 66–68% male; mean body weight 7.4–7.5 kg) were referred to a tertiary paediatric allergy centre for a diagnostic double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) for suspected CMPA. Infants with a positive result were randomized to one of the study’s formulae. During the study, patients were managed by their family practitioner and a dietitian. Additionally, they attended the tertiary paediatric allergy centre at 1, 2 and 3 years after randomization to undergo a skin prick test and a DBPCFC to assess whether they were still allergic to cow’s milk. At these visits, the children were physically examined by a paediatrician, body growth was assessed and a structured interview was undertaken to assess any health problems, including the development of any allergic manifestations.

Allergic urticaria was diagnosed if at least two episodes of itching eruptions or swelling with typical appearance were observed by the parents or a physician and were caused by the same allergen. Atopic eczema was diagnosed based on pruritus, typical morphology and distribution, a chronic or chronically relapsing course, and personal or family atopic history. Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis was diagnosed based on the symptoms of rhinitis, such as nasal congestion, sneezing, itching, rhinorrhoea, current use of medication for these symptoms and/or conjunctivitis, after exclusion of infection. A diagnosis of asthma was based on the presence of recurrent wheeze (more than once a month), difficulty in breathing, chest tightness or both; cough (worse at night); clinical improvement during treatment with short-acting bronchodilators and inhaled steroids; and worsening when treatment was stopped. Alternative causes of recurrent wheezing were considered and excludedCitation12.

Infants were excluded from the study if they had cow’s milk protein induced anaphylaxis, food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome, other food allergies, other allergic diseases, non-CMPA-related atopic eczema, eosinophilic disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, chronic systemic diseases, congenital cardiac defects, active tuberculosis, autoimmune diseases, immunodeficiency, chronic inflammatory bowel diseases, coeliac disease, cystic fibrosis, metabolic diseases, malignancy, chronic pulmonary diseases, malformations of the gastrointestinal and/or respiratory tract, or were fed prebiotics or probiotics in the four weeks before enrolmentCitation12.

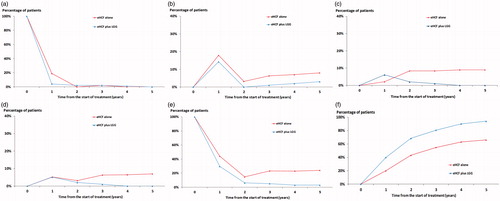

The study reported that, at 3 years, 2.0%, 1.0%, 1.0% and 2.0%, of infants fed eHCF plus LGG were experiencing urticaria, eczema, asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis, respectively, compared with 2.1%, 6.3%, 8.4% and 16.8% of those fed an eHCF aloneCitation12. Additionally, 81% of infants fed eHCF plus LGG had acquired tolerance to cow’s milk (defined as the negativization of a double-blind food challenge) by 3 years compared to 55% of those fed an eHCF aloneCitation12. Time-series forecasting was used to extrapolate the percentage of children experiencing allergic symptoms or acquiring tolerance to cow’s milk with each formula up to 5 years (). These percentages were used to populate the model with the probability of infants experiencing urticaria, eczema, asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis or developing tolerance to cow’s milk at 12-monthly intervals up to 5 years ().

Figure 2. Time-series forecasting of the clinical outcomes from the RCTCitation12. (a) Manifestation of urticaria; (b) manifestation of eczema; (c) manifestation of asthma; (d) manifestation of rhinoconjunctivitis; (e) manifestation of symptomatic patients; (f) acquisition of tolerance to cow’s milk.

Table 1. Annual transition probabilities in the Markov model.

Model inputs – resource use

The model was populated with estimates of healthcare resource use pertaining to the management of infants with CMPA in the UK. These estimates were derived from the interviewed GPs who managed infants with CMPA according to their local clinical protocol and guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)Citation13. The estimates of resource use derived from the interviewed GPs that were incorporated into the model are summarized in .

Table 2. Estimates of resource use incorporated into the model.

According to the clinicians, infants would receive a mean of 11 cans of clinical nutrition per month up to 6 months of age, a mean of 9 cans per month between 6 and 12 months of age, a mean of 7 cans per month between 12 and 18 months of age and, in some practices, a mean of 6 cans per month between 18 and 24 months of age.

Model outputs

The primary measure of clinical effectiveness was the probability of being free of allergic symptoms (i.e. urticaria, eczema, asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis). The secondary measure of clinical effectiveness was the probability of acquiring tolerance to cow’s milk.

Unit costs at 2017/18 prices ()Citation14,Citation15 were assigned to the estimates of resource use in order to calculate the NHS cost of healthcare resource use per patient. Costs were discounted from the second and subsequent year at 3.5% per annum, in accordance with the recommended rateCitation16.

Table 3. Unit resource costs at 2016/17 prices.

The model was used to estimate the cost-effectiveness of using eHCF plus LGG compared with an eHCF alone in terms of the incremental cost for each additional infant who was: (1) symptom free and (2) tolerant to cow’s milk. This was calculated as the difference between the expected costs of the two dietetic strategies divided by the difference between the probabilities of effectiveness of the two strategies. If one of the formulae improved outcome for less cost, it was considered to be the dominant (cost-effective) dietetic strategy.

Sensitivity analyses

To assess uncertainty within the model, probabilistic sensitivity analysis was undertaken (10,000 iterations of the model) by simultaneously varying the probabilities, clinical outcomes, resource use values and unit costs. A beta distribution was used to represent uncertainty in probability values by assuming a 10% standard error around the mean values. Resource use estimates and unit costs were varied randomly according to a gamma distribution by also assuming a 10% standard error around the mean values. The outputs from these analyses were used to estimate the probability of eHCF plus LGG being cost-effective at different willingness to pay thresholds over 5 years.

In addition, deterministic sensitivity analyses were performed to identify how the incremental cost-effectiveness of eHCF plus LGG compared with an eHCF alone would change by varying different parameters in the model.

Results

Probability of allergic manifestation and acquiring tolerance to cow’s milk

The probability of allergic manifestation was lower among infants who were initially fed with eHCF plus LGG. Similarly, the probability of developing tolerance to cow’s milk was higher among infants who were initially fed with this formula ().

Table 4. Expected clinical outcomes at three and five years from the start of treatment.

Healthcare resource use and corresponding costs

An infant who is initially managed with eHCF plus LGG was estimated to consume fewer healthcare resources than infants managed with an eHCF alone (). Hence, initially feeding infants with eHCF plus LGG instead of the other formula is expected to free up healthcare resources for alternative use by other patients. Consequently, the total healthcare cost of initially feeding infants with eHCF plus LGG was estimated to be less than that of feeding infants with an eHCF alone ().

Table 5. Mean amount of resource use per patient over five years from the start of treatment.

Table 6. Mean cost (at 2016/17 prices) per patient over five years from the start of treatment (percentage of total cost in parentheses).

The cost of managing CMPA/urticaria accounted for up to 92% and 88% of the total cost of managing patients in the eHCF plus LGG and eHCF alone groups, respectively. Managing asthma accounted for a further 3% and 6% of the total cost of managing patients in the eHCF plus LGG and eHCF alone groups, respectively. Managing eczema and rhinoconjunctivitis accounted for the remainder. This cost distribution was to be expected since all the infants in the study had CMPA and the acquisition costs of the prescribed formulae for managing the allergy were the primary cost driver of patient management (). GP visits were the secondary cost driver (), the majority of which were for CMPA/urticaria (). Only a small proportion of infants in the study developed eczema, asthma or rhinoconjunctivitis. Therefore, the additional amount of resource use due to these allergic manifestations was small relative to the amount of resources required to manage the CMPA.

Cost-effectiveness analyses

Feeding infants with eHCF plus LGG instead of an eHCF alone resulted in a greater probability of being symptom free and of developing tolerance to cow’s milk for a lower cost (). Hence, starting feeding with eHCF plus LGG was found to be the dominant strategy from the perspective of the UK’s NHS (). Additionally, the probability of children being asthma free at 3 years after the start of treatment was 0.99 and 0.92 in the eHCF plus LGG and eHCF alone groups, respectively and at 5 years it was 0.99 and 0.91 in the eHCF plus LGG and eHCF alone groups, respectively. Hence initially feeding IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergic infants with eHCF plus LGG was also viewed as a dominant dietetic strategy when the measure of cost-effectiveness is the incremental cost for each additional infant who was asthma free.

Table 7. Cost-effectiveness analyses at three and five years from the start of treatment.

Sensitivity analyses

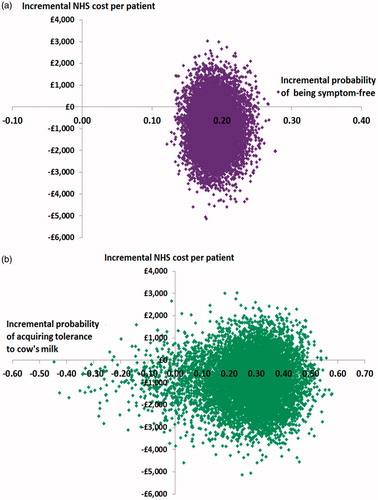

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses enabled the distribution in the incremental costs and incremental probabilities of the alternative formulae at 5 years following the start of treatment to be generated (). Outputs from these analyses showed that from the NHS’ perspective, at an incremental cost-effectiveness threshold of £11.21 (i.e. the cost of a 400 g can of eHCF plus LGG) for each additional infant becoming:

Figure 3. Scatterplot of the incremental cost-effectiveness of eHCF plus LGG compared to eHCF alone (10,000 iterations of the model); (a) Measure of effectiveness is probability of being symptom-free; (b) measure of effectiveness is probability of acquiring tolerance to cow’s milk.

free of allergic symptoms, up to 79% of a cohort would be cost-effectively treated with eHCF plus LGG compared to an eHCF alone.

tolerant to cow’s milk, up to 80% of a cohort would be cost-effectively treated with eHCF plus LGG compared to an eHCF alone.

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses also showed that at an incremental cost-effectiveness threshold of £11.21 for each additional infant becoming asthma free, up to 78% of a cohort would be cost-effectively treated with eHCF plus LGG compared to an eHCF alone.

Sensitivity analyses () indicated that extrapolating the outcomes from the RCTCitation12 from 3 to 5 years has negligible impact on the relative cost-effectiveness of eHCF plus LGG. Additionally, changes in the estimates of resource use also have negligible impact on the relative cost-effectiveness of eHCF plus LGG (). The base case analysis assumes that the cost of the two formulae is the same. The sensitivity analyses () showed that, if the cost of eHCF alone is reduced to £9.20 per 400 g can, then initial treatment with eHCF plus LGG still affords a cost-effective dietetic strategy as the total healthcare cost at 5 years after the start of treatment with this formula was estimated to be a discounted £500 less than that of feeding infants with an eHCF alone.

Table 8. Sensitivity analyses.

Discussion

This study is the first to show that initial management with eHCF plus LGG affords a cost-effective dietetic strategy over a period of 5 years (irrespective of whether the measure of effectiveness is acquiring tolerance to cow’s milk or being free of the symptoms of urticaria, eczema, rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma). The analysis is constrained by the fact that only infants with IgE-mediated CMPA were evaluated and the only comparator formula was an eHCF alone. Notwithstanding this, the underlying IgE mediation of the allergy suggests that this population is at a higher risk of developing other allergies such as eczema, rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma than those with non-IgE-mediated CMPACitation12.

Other limitations reflect the fact that the clinical basis of the economic analysis was the RCT conducted in ItalyCitation12. The advantage of using this clinical data was that the treatment effect reflects the findings from a RCT. However, the findings from a protocol-driven RCT may not necessarily be reproducible in the UK or reflect clinical practice in the UK. Additionally, the analysis was informed with assumptions about management patterns from four centres in the UK. Hence, the estimated levels of healthcare resource use incorporated into the model may not be representative of the whole UK. However, changes to these estimates had negligible effect on the results.

The model used resource estimates for the “average infant” and does not consider the impact of other factors that may affect the results, such as co-morbidities, underlying disease severity and pathology of the underlying disease. The model also excluded the possibility of infants experiencing multiple allergic manifestations either at initial presentation or during the subsequent 5 years; however, this is unlikely to affect the relative cost-effectiveness of the two formulae. The results of the 3 year RCT were extrapolated to 5 years, but this had negligible impact on the results (as shown in ). Additionally, the study excluded the cost and consequences of managing children beyond this period. The analysis also excluded the indirect costs incurred by society as a result of employed parents taking time off work and non-treatment-related costs incurred by parents. Changes in quality of life and improvements in general well-being of sufferers and their parents as well as parents’ preferences were also excluded. Consequently, this study may have underestimated the relative cost-effectiveness of eHCF plus LGG.

The results from this economic analysis were based on extrapolating the clinical results from the aforementioned RCTCitation12 from 3 to 5 years, since many planning authorities allocate resources over a 3 to 5 year fiscal period. However, the economic analysis also showed that initial management with eHCF plus LGG affords a cost-effective dietetic strategy over a period of 3 years across all measures of effectiveness. Additionally, we have previously reported that initial management of both IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated CMPA with eHCF plus LGG affords a cost-effective dietetic strategy when compared to both an eHCF alone and amino acid formulae over a period of 18 months in different countriesCitation6–10. Consequently, our studies would suggest that the probability of eHCF plus LGG being a cost-effective formula for the initial management of CMPA is sustained from 18 months over a period of 5 years. Moreover, the relative cost-effectiveness of the formula increases as the time horizon lengthens. This is relevant since the most recent evidence suggests that the natural history of CMPA has changed over time, with the proportion of children with disease persistence increasing through to 5 years and possibly olderCitation17,Citation18.

The distribution and pattern of allergies change as a child matures. Infants are more likely to present with food allergy, atopic eczema, gastrointestinal symptoms and wheezing, whilst older children typically present with asthma and allergic rhinoconjunctivitisCitation19. Furthermore, children in the US with a food allergy are up to four times more likely to have other allergic manifestations, such as asthma (4.0 times), atopic eczema (2.4 times) and respiratory allergies (3.6 times), compared with children without a food allergyCitation20. Hence, reducing the risk of asthma manifestation in infants with CMPA can have substantial clinical and economic sequelae over the medium to long term. Children’s health in the UK has been reported to lag behind other Western European nations and unplanned hospital admissions have steadily increasedCitation21,Citation22. Hospital admissions have been increasing partly due to the challenges faced by the NHS in adapting to a growing chronic disease burden in childrenCitation22 and policies that seem to have delayed children’s access to primary careCitation23. In a cohort study among 319,780 children born between January 2000 and March 2013, 8.9% of the cohort had a diagnosis of asthmaCitation24. These children had a mean of 2.2 asthma-related visits per year with their general practitioner between the ages of 5 and 9 years and 84 unplanned asthma-related hospital admissions per 1000 childrenCitation24. Additionally, in 2016/17, there were 24,467 hospital admissions for asthma among children aged 9 years or less. This number increases to 31,427 asthma-related admission when children aged 10 to 14 years are includedCitation25. Moreover, asthma has a major impact on absenteeism from schoolCitation26.

In recent years, hospital admission rates for adults with chronic diseases, such as asthma, are reported to have fallen following incentives in primary care to improve chronic disease managementCitation27. This suggests that there is scope for a similar policy intervention for children, although the healthcare needs of children differ from those of adults since there is a greater dependency on parents, and education remains an important component of a family’s ability to care. Such a policy might include feeding infants with IgE-mediated CMPA with eHCF plus LGG, not only because it is a cost-effective dietetic strategy, but because of its potential to reduce asthma in children. Further work is required to better understand how primary care can serve the needs of children with allergies in order to minimize the risk of paediatric allergies leading to long-term or complex conditions.

In conclusion, within the study’s limitations, first-line management of newly diagnosed infants with IgE-mediated CMPA with eHCF plus LGG instead of an eHCF alone improves outcome, releases healthcare resources for alternative use, reduces the NHS cost of patient management and affords a cost-effective dietetic strategy to the NHS in 80% of cases.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This paper was funded by Mead Johnson Nutrition, Slough, Berkshire, UK.

Author contributions

J.F.G. conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. H.S. contributed to the analyses, and critically reviewed and contributed to the revised manuscript. Both authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Mead Johnson Nutrition had no influence on: (1) the study design; (2) the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; (3) the writing of the manuscript; or (4) the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of Mead Johnson Nutrition. The authors wish to thank the following general practitioners for their contributions to this study: Aashish Bansal, Colindale, London, UK; Helen Howells, Southampton, UK and Chair of the Primary Care section of the British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; Ursula Mason, Carryduff, County Down, UK; and Joanne Walsh, Norwich, UK.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with formatting errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2019.1625595.

References

- Sicherer SH. Epidemiology of food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:594–602.

- Koletzko S, Niggemann B, Arato A, et al. Diagnostic approach and management of cow’s-milk protein allergy in infants and children: ESPGHAN GI Committee practical guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:221–229.

- Venter C, Arshad SH. Guideline fever: an overview of DRACMA, US NIAID and UK NICE guidelines. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:302–315.

- Berni Canani R, Nocerino R, Terrin G, et al. Effect of lactobacillus GG on tolerance acquisition in infants with cow’s milk allergy: a randomized trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:580–582, 582.e581–585.

- Berni Canani R, Nocerino R, Terrin G, et al. Formula selection for management of children with cow’s milk allergy influences the rate of acquisition of tolerance: a prospective multicenter study. J Pediatr. 2013;163:771–777.e771.

- Guest JF, Panca M, Ovcinnikova O, et al. Relative cost-effectiveness of an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula containing the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in managing infants with cow’s milk allergy in Italy. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;7:325–336.

- Guest JF, Weidlich D, Mascunan Diaz JI, et al. Relative cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula containing the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in managing infants with cow’s milk allergy in Spain. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;7:583–591.

- Guest JF, Weidlich D, Kaczmarski M, et al. Relative cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula containing the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in managing infants with cow’s milk allergy in Poland. CEOR. 2016;8:307–316.

- Guest JF, Kobayashi RH, Mehta V, et al. Cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in managing infants with cow’s milk allergy in the US. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34:1539–1548.

- Ovcinnikova O, Panca M, Guest JF. Cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula plus the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG compared to an extensively hydrolyzed formula alone or an amino acid formula as first-line dietary management for cow’s milk allergy in the US. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;7:145–152.

- Waserman S, Begin P, Watson W. IgE-mediated food allergy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018;14:55.

- Berni Canani R, Di Costanzo M, Bedogni G, et al. Extensively hydrolyzed casein formula containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG reduces the occurrence of other allergic manifestations in children with cow’s milk allergy: 3-year randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1906–1913.e1904.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Food allergy in under 19s: assessment and diagnosis [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2018 Nov 30]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg116

- NHS Digital. National schedule of reference costs 2016–17 [Internet] [cited 2018 Nov 30]. Available from: https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/reference-costs/

- Curtis LA, Burns A. Unit costs of health and social care 2017 [Internet] [cited 2018 Nov 30]. Available from: http://www.pssru.ac.uk

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2018 Dec 24]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg9/resources/guide-to-the-methods-of-technology-appraisal-2013-pdf-2007975843781

- Skripak JM, Matsui EC, Mudd K, et al. The natural history of IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1172–1177.

- Wood RA, Sicherer SH, Vickery BP, et al. The natural history of milk allergy in an observational cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:805–812.

- BSACI. Allergy in children [Internet] [cited 2018 Dec 24]. Available from: https://www.bsaci.org/resources/allergy-in-children

- Branum AM, Lukacs SL. Food allergy among children in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1549–1555.

- Cecil E, Bottle A, Sharland M, et al. Impact of UK primary care policy reforms on short-stay unplanned hospital admissions for children with primary care-sensitive conditions. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:214–220.

- Wolfe I, Thompson M, Gill P, et al. Health services for children in western Europe. Lancet. 2013;381:1224–1234.

- Cecil E, Bottle A, Cowling TE, et al. Primary care access, emergency department visits, and unplanned short hospitalizations in the UK. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20151492.

- Cecil E, Bottle A, Ma R, et al. Impact of preventive primary care on children’s unplanned hospital admissions: a population-based birth cohort study of UK children 2000–2013. BMC Med. 2018;16:151.

- NHS Digital. Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity, 2016–17 [Internet] [cited 2018 Dec 24]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-admitted-patient-care-activity/2016-17

- Asthma UK. Time to take action on asthma [Internet] [cited 2018 Dec 24]. Available from: https://www.asthma.org.uk/globalassets/campaigns/compare-your-care-2014.pdf

- Harrison MJ, Dusheiko M, Sutton M, et al. Effect of a national primary care pay for performance scheme on emergency hospital admissions for ambulatory care sensitive conditions: controlled longitudinal study. BMJ. 2014;349:g6423.