Abstract

Background: The unique extract of a mixture of Baptisiae tinctoriae radix, Echinaceae pallidae/purpureae radix and Thujae occidentalis herba alleviates the typical symptoms of the common cold and shortens the duration of the disease.

Purpose: The risk-benefit ratio of a concentrated formulation of this herbal extract was investigated under everyday conditions.

Study design: Pharmacy-based, non-interventional, multicenter, open, uncontrolled study registered at DRKS00011068.

Methods: For 10 days, patients completed a diary questionnaire rating the severity of each common cold symptom on a 10-point scale. For evaluation, symptoms were combined into the scores “overall severity”, “rhinitis”, “bronchitis” and “general symptoms”. Cox models were used to evaluate the influence of covariates on the time of stable improvement.

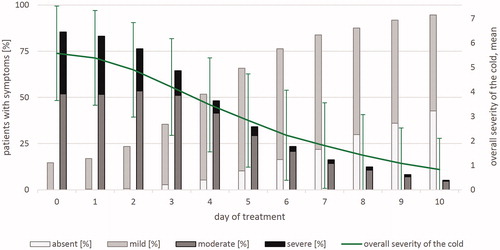

Results: In total 955 patients (12 to 90 years) were analyzed; 85% assessed the efficacy as good or very good. Response (improvement of the overall severity by at least 50%) was reached at median day 5 (95% CImedian 5-5). General symptoms abated faster than the other complaints. The percentage of predominantly moderate or severe symptoms to predominantly mild or absent symptoms reversed on day 3.9 (interpolation). Results of adolescents and adults did not differ (p = .6013; HR = 0.918). Concomitant medication did not boost the effect of the herbal remedy. Early start of treatment of the cold accelerated the recovery (p = .0486; HR = 0.814). Thirty-four cases of adverse events were self-recorded in the diaries; none of them were serious. The tolerability was assessed as “good or very good” by 98% of the patients.

Conclusion: The benefit–risk assessment of this herbal extract clearly remains positive. This non-interventional study accords with and shows transferability of the results of previous placebo-controlled studies with this extract in a real-life setting.

Introduction

Mild upper respiratory disease is commonly referred to as the common cold. Characteristic symptoms are nasal congestion and discharge, sneezing, sore throat, cough, and general complaints such as headache and body aches. Colds are caused by various pathogens, especially viruses. They are usually self-limiting and restricted to the upper respiratory tract. Colds can lead to enormous health and economic burdensCitation1,Citation2.

Treatment of viral respiratory tract infections targets the causal pathogen, the symptoms or the immune status of the host. In most cases, antibiotic therapy is not helpful since most infections are induced by viruses. Antiviral agents and symptomatic or immunomodulatory drugs are treatment optionsCitation3. Patients mainly choose the last two mentioned strategies. For colds, self-medication with over-the-counter drugs is more popular than a doctor’s visit in GermanyCitation4. Here, the interest in phytotherapeutics is widespread and accepted as effective treatment.

Popular herbal remedies with immunomodulating properties include preparations of Echinacea spp., Thuja occidentalis and Baptisia tinctoria. The effects of Echinacea spp. on the immune system have been demonstrated by a series of experimentsCitation5. These remedies are used to prevent or treat colds. The mechanism of action is associated with its ability to stimulate the innate immune responseCitation5–9. Alkamides, glycoproteins, polysaccharides and caffeic acid derivatives are the main active ingredients in echinaceaCitation10. Insufficiency of clinical evidence is criticized due to the variety of dosages and echinacea preparationsCitation10–12. Each preparation should be judged individuallyCitation13.

Thuja occidentalis extracts are antiviral against wartsCitation14, anti-inflammatory, antioxidative and affect cell-mediated immune responses and cytokine levelsCitation15–18. Similar to most herbal preparations, Thuja occidentalis extracts and Baptisia tinctoria extracts comprise multitudes of substances which contribute or may contribute to their multi-target immunomodulatory activities. The set of active contributors in Thuja occidentalis extracts mainly includes essential oils, flavonoids and polysaccharidesCitation19, and in Baptisia tinctoria extracts contain mainly arabinogalactans and arabinogalactan proteinsCitation20. Baptisia tinctoria extracts stimulate lymphocytes and elevate antibody productionCitation21,Citation22.

The synergism of Echinacea, Thuja and Baptisia is utilized in an extract of a mixture of these herbs against colds (Esberitox1 Compact – 16 mg/tablet, one tablet three times daily). Double-blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials (RCT) have confirmed the clinical efficacy of phytomedicines containing this unique extract; it accelerates improvement of symptoms and shortens the duration of the diseaseCitation23–25. These studies investigated the same native extract in a lower amount per tablet but larger number of tablets per day reflecting a similar daily dose range. To confirm the transferability of the RCT-based proof of the medicine’s favorable risk–benefit ratio in a real-life setting, the concentrated compact form, with an elevated amount of extract per tablet, was examined in a pharmacy-based, non-interventional study.

Methods

Study design and participants

This non-interventional study (NIS) was pharmacy-based, post-marketing, multicentric, open, observational and without control group. In this real-life setting, patients, who bought the phytomedicine in their local pharmacy to treat their colds, were asked to assess their symptoms in a common cold diary. A total of 180 pharmacies throughout Germany participated in this study from September 2016 until April 2017. The inclusion criteria were: written consent to data collection, minimum age 12 years and no contraindication as per package leaflet (PIL) (Supplemental data B). Concomitant medication was not excluded but should have been recorded in the patient’s diary. The pharmacists made no intervention at all.

Ethics and data protection

The study was approved by the Freiburg Ethics Commission International (feci-code: 016/1595) and the German authority (BfArM) was notified. The rules of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki and current laws and regulations in Germany were considered. National health insurance associations were notified of the study and it was registered at the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00011068) which is linked to the WHO registry platform ICTRP (http://apps.who.int). The study was conducted without deviations from the study protocol. A report is available from these study registries. Prior to participation, the patients were informed on and consented to pseudonymized study data collection in writing. Every diary had a unique number without collecting sensitive data like name or birth date.

Study medication

Esberitox Compact is used for supportive therapy of viral common colds. One tablet contains 16 mg of a native dry extract (drug extract ratio 4–9:1) from Baptisia tinctoria root, Echinacea purpurea root/Echinacea pallida root, and Thuja occidentalis tips and leaves at a ratio of 4.92:1.85:1.85:1. The extraction solvent is ethanol 30% (V/V). This product holds a marketing authorization from the relevant regulatory authorities who received the dossier on its pharmaceutical quality. The recommended dosage is one tablet three times daily for adults and adolescents (≥12 years). Contraindications are hypersensitivity to any of the active substances or excipients and pre-existing illnesses like progressive systemic diseases, autoimmune diseases, acquired immunodeficiency, immunosuppression or hematological diseases of the white blood cell system. The patients were referred to the PIL (therein, for example, treatment duration of up to 10 days is recommended) but were not given any further instructions (Supplemental data B). A real-life setting was intended.

Common cold diary and logbook

The patient’s common cold diary requested general information and common cold symptoms before onset of administering the study medication, in the evening after the first administration, and every one or two days during treatment thereafter. Eleven symptoms were queried by means of 10-point numerical scales: blocked nose, runny nose, I often have to blow my nose, I often have to sneeze, cough, hoarseness, productive cough, pain in the chest area, sore throat/swallowing difficulties, aching head and limbs, and overall severity of the cold. Demographic data, medical history data, state of health, administration habits, dosage, concomitant medication, side effects and assessments completed the patient’s diary. The severity of the symptoms was rated as follows: 0 = no symptoms, 1–3 = mild symptoms, 4–6 = moderate symptoms and 7–9 = severe symptoms. This questionnaire was generated based on the earlier placebo-controlled studyCitation23 to ensure comparability of the efficacy assessment.

The pharmacists were required to document all approaches to Esberitox Compact customers in a logbook and were instructed to note all refusals, when possible together with the reasons stated. Package size sold, sex and age group of the customer were also recorded.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the risk-benefit ratio of the herbal remedy under everyday conditions. The “benefit” was based on the diary records of the cold symptoms and overall assessment of efficacy. The cold symptoms were combined into a global cold score (item “overall severity of the cold”), a rhinitis score (mean of items “blocked nose”, “runny nose”, “I often have to blow my nose” and “I often have to sneeze”), a bronchitis score (mean of items “cough”, “hoarseness”, “productive cough” and “pain in the chest area”), a general complaints score (item “aching head and limbs”) and a total score. The symptom “sore throat/swallowing difficulties” was analyzed separately. The “risk” comprised adverse drug reactions during the treatment and the patient’s overall assessment of tolerability.

Secondarily, patients rated their satisfaction with the herbal medicinal product.

Statistics

Data set

Logbooks and diaries underwent standard data management checks addressing missing values and implausible data. All returned, evaluable diaries were analyzed. Diaries without information on therapy and/or efficacy and/or tolerability and diaries from patients without signs of common cold at start of treatment were excluded from the analysis.

Data analysis

A statistical analysis plan was generated prior to data analysis. The analysis provided descriptive statistics for continuous data and frequency distributions for ordinal data. SAS version 9.4 software was used.

The symptom scores were distributed ranging from “0” (= absent) to maximum “9” (= most severe manifestation); all of which were frequented. In patients with a score ≥1, improvement (“response”) was defined as stable reduction to ≤50% of baseline. The total score T was defined as the sum of the N(0,1) transformed scores (“overall severity of the cold”, “rhinitis score”, “bronchitis score” and “general symptoms”). “Response” of the total score was defined as stable reduction of T + 3.967 to ≤50% of the baseline where -3.967 represents the sum of the N(0,1) transformed values “absent” for all four scores in terms of the study data.

Cox regression models evaluated the influence of covariates on the time of stable improvement providing hazard ratios (HRs) for influence variables. The following variables were reviewed for influencing the total score: age <18, age >50, sex, duration of cold ≤1 day, duration of cold >3 days, >2 colds a year, active smoker, premedication. Concomitant medication was also considered in the analyses of the single scores by Cox regression; here the most prominently used co-medication was decisive.

Adverse events (AEs) were coded according to MedDRA and assessed for causal relationship.

Handling of missing data

Missing values were designated and not included in calculating percentages.

Rhinitis score, bronchitis score and general symptoms were based on completely documented symptoms. Missing documentation of symptoms therein or of the parameter “overall severity of the cold” was replaced according to a prespecified imputation strategy (Supplemental data D). Missing values of other variables were not replaced, apart from their use as cofactors in regression models. In this analysis, cofactors were defined as 0–1 indicator variables with “1” as the characteristic of interest; missing values were assigned to “0”.

Results

Study participation

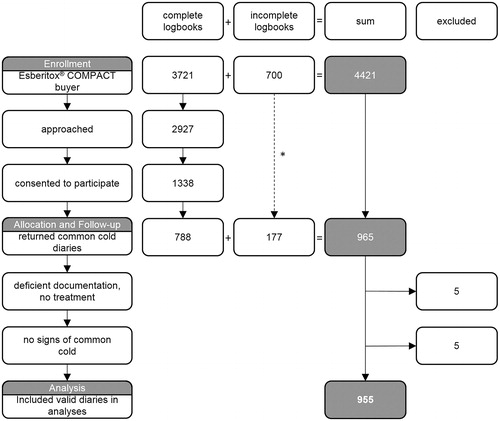

Data from 955 patients were included in the study analysis. A total of 4421 users of the investigated phytomedicine were the basis (). Of the approached patients (N = 2927 from complete logbooks), 1338 cases (45.7%) consented to participate. The main reasons documented for non-participation were “no interest” and “no time” (sum 73.2%). Thereof, 788 diaries were returned by the participants (response rate 58.9%). Knowledge of another 700 users with 177 diaries was obtained from incomplete logbooks and patients, with information only from their diaries. Thus, a total of 965 diaries were returned. Thereof, five diaries were excluded due to insufficient documentation. Eight out of the remaining 960 patients, from 155 pharmacies, discontinued therapy due to side effects. Another five diaries came from patients without “overall severity of the cold” before first administration of the tablets. These preventive users were excluded from the analyses of therapeutic efficacy. The first documented observation was dated 23 September 2016 and the last 17 May 2017.

Figure 1. Participant flow. A total of 965 out of 4421 documented users of the phytomedicine actively participated in the study (21.8%). *The branch with incomplete documentation of the participant flow by the pharmacy. Ten diaries were excluded from analyses. CONSORT requirements (grey background) as well as study specific additional data (white background) are considered.

Compliance

The patients were 12 to 90 years in age, complying with the lower limit (12 years) in the PIL (Supplemental data B). Three patients did not adhere to the contraindications. No side effects were reported in these cases.

The number of days with documented administration of the herbal remedy varied between 1 and 10 with a median of 7 days. The total dose varied between 1 and 53 tablets with a median of 21 tablets. Depending on the treatment day, 75–92% of patients performed the treatment as recommended in the PIL (three tablets per day) (Supplemental data B).

During the 10-day therapy, the daily dose was exceeded in 64 cases by up to 9 tablets. In two of these cases side effects were reported but were without causal relationship. Eleven patients exceeded the total dose of 30 tablets in 10 days. No side effects were observed in these patients.

Five patients used the immunomodulator as prophylactic medication.

General and baseline data

A total of 955 patients aged 12 to 90 years (median 39 years) were included in the analyses (). The group of 31–50 year old patients predominated (41.8%); 65.6% of patients were female. The age distributions of male and female patients were similar (χ2 test: p = .7990). Seventeen percent were active smokers. Thereof, 32.7% had a history of >2 colds per year compared with 26.4% of the non-smokers.

Table 1. Demographic data, N = 955.

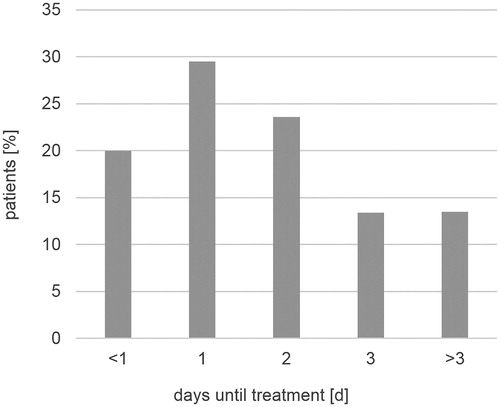

In the histories, there were predominantly 1–2 colds a year. Most patients started their therapy with the product on day one (29.5%), two (23.6%) or at the onset (20%) of their cold ().

Figure 2. Duration of common cold until begin of therapy with the investigated phytomedicine. N = 955.

Various additional diseases were present in 27.3% of patients, mainly immune system disorders (allergies; 14.2%), vascular disorders (hypertension; 4%), and respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders (asthma; 3.1%). Concomitant medication was used by 63.9% (610/955) of the patients ().

Table 2. Concomitant medications, N = 955.

Common cold scores before first administration are listed in . Most frequent severe symptoms were reported in the following order: “blocked nose” (32.6%) > “I often have to blow my nose” > “sore throat/swallowing difficulties” > “aching head and limbs” > “runny nose” > “cough” > “I often have to sneeze” > “hoarseness” > “productive cough” > “pain in the chest area” (7%).

Table 3. Baseline common cold scores, N = 955.

Efficacy

At the end of therapy, the patients had no or improved symptoms in 79% (“productive cough”) to more than 90% (“sore throat/swallowing difficulties”) of the cases (symptoms of rhinitis: 85.8–93.8%). Pre–post comparisons of changes in the total score showed that 96% of the patients had no or improved symptoms. The cold remained unchanged or worsened in 4% of the users (missing values 5; N = 955).

A stable improvement of the overall severity of the cold by at least 50% during treatment with the investigated phytomedicine was reached at day 5 (95% CImedian 5-5) (1st quartile = 4, 3rd quartile = 7, mean = 5.19 [95% CImean 5.05-5.32], N = 955). The response rates were 92.6% and 93.2% for “overall severity of the cold” and “total score”, respectively. The single score that contributed the most to the general improvement was the “general symptom” score. General symptoms abated faster than the other complaints.

Overall, the course of disease was mainly determined by rhinitis. The “overall severity of the cold” score, with percentages of severity grades (absent/mild/moderate/severe) over the course of a 10-day treatment after imputation of missing values, is shown in . The percentage of predominantly moderate or severe symptoms to predominantly mild or absent symptoms reversed on day 3.9 (interpolation, N = 955).

Factors influencing efficacy

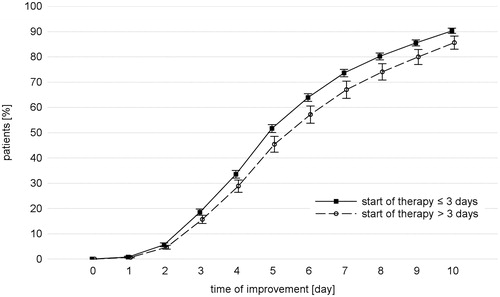

The influence of covariates on the time of stable improvement was evaluated as described in Data analysis. A significant influence was ascertained only for “duration of disease >3 days”, namely in a reduction of the time to stable improvement if therapy started ≤3 days after onset of the disease (p = .0486; HR = 0.814; 95% CI = 0.663-0.999). visualizes this influence.

Figure 4. Impact of start of treatment. Time of stable improvement of the total score considering the duration of the cold before treatment with the phytomedicine. N = 955.

There was no relevant difference between adolescents (12 to 18 years) and adults (18 years or older) regarding time to stable improvement (p = .6013; HR = 0.918). In this observational study, the smokers’ histories showed more frequent colds than the non-smokers. The smoking habits did not influence the efficacy of the herbal remedy.

Concomitant medications () were also reviewed for confounding the time to stable improvement. Cough and cold preparations (R05) were associated with a slower improvement (p = .0001; HR = 0.731), i.e. the time to stable improvement of the bronchitis score was longer if cough and cold preparations were used in addition to the phytopharmaceutical product compared with cases where no cough and cold preparations were used. This circumstance is closely related to the severity of bronchitis symptoms at baseline. Patients who additionally took cough and cold preparations (R05) did not have a heavier cold but had a higher bronchitis score than patients who abstained from them (p = .0001; median 2.5 vs. 2.0 at baseline).

The influence of nasal preparations (R01), throat preparations (R02), anti-inflammatory and anti-rheumatic products, and analgesics (M01, N02) was marginal or not statistically relevant with p = .1343, p = .9377 and p = .1126 (all HR < 1, favoring no other concomitant medication), respectively.

Tolerability

Forty-seven adverse events (MedDRA Preferred Terms) were self-recorded by 34 patients. None of them were serious. All AEs were mentioned in the PIL (Supplemental data B), no unknown AE occurred. A possible causality with the investigated phytomedicine was judged in 17 cases (24 AEs). These adverse events were allocated to the following System Organ Classes (MedDRA Preferred Terms): gastrointestinal disorders (15 AEs), skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (6 AEs), nervous system disorders (2 AEs) and cardiac disorders (1 AE). No adverse drug reactions were observed in adolescents.

Patients’ assessments

A total of 33.6% of the patients rated the therapy as “very good” and 84.5% as “good or very good”; no effect was mentioned in 2.3% of the patients. The low rate of adverse events gave rise to “good or very good” tolerability assessments by 98% of the consumers. The results of these efficacy and tolerability assessments did not differ between adults and adolescents (p = .618 and p = .385, respectively). Satisfaction with treatment was assessed by 35.8% as “very satisfied” and by 93.8% as “satisfied or very satisfied”; 74.4% want to use this investigated phytomedicine again for a future cold.

Discussion

This study contributes to the positive benefit–risk ratio of this concentrated formulation of this unique herbal extract preparation under everyday conditions. This accords with recent studies, which confirmed efficacy and demonstrated safety as well as tolerability.

The novelty of our study is that it broadens the existing RCT-based evidence on the investigated phytomedicine to the real life situation of common colds which nowadays primarily takes place in pharmacies. The study results show the transferability of the RCT results to the real life situation in the therapy of common colds. Representativity of study results is an important scientific issue, so that RCTs and observational studies complement each other in terms of external and internal validity of their conjoined evidence. Moreover, our study used an innovative study setting, i.e. exemplifies the feasibility of pharmacies to serve as investigator sites for clinical studies in prescription-free medicinal products.

The questionnaire used in the diaries was highly similar to other questionnaires from various clinical studiesCitation26–28 and considered the main symptoms during a coldCitation1. The questionnaire included eleven questions regarding cold symptoms. These questions were developed based on experience in a previous clinical study where the well-being score showed the greatest improvement followed by the rhinitis score and, slightly behind it, the bronchitis scoreCitation23. In the current and the previous studyCitation23 the greatest improvement was shown in “general symptoms” and “well-being”, respectively.

Some pharmacies did not strictly complete the logbooks. Nevertheless, this did not impair the validity of the diaries. In addition to known limitations of non-interventional studies, this pharmacy-based study waived involvement of medical doctors. However, since patients usually self-medicate their colds with over-the-counter drugs without consulting physicians, our approach reflects the real-life situation with excellent compliance and high response in terms of returned diaries.

Participation of more than 4000 consumers led to nearly 1000 evaluable patient diaries. Only a few records had to be excluded. Therefore, the statistical analysis plan was realized as intended.

This study was not able to include a placebo group due to its non-interventional setting; therefore, a comparison of the investigated efficacy has limitations. Nevertheless, the results of this study accord with previous experience with the same native extract in a placebo-controlled clinical trialCitation23. That study used similar assessment methods and proved the efficacy of the herbal remedy to be superior to placebo. The time to stable improvement of cold symptoms (≤50% of baseline) was reached 2 to 3 days faster than in the placebo group, i.e. at about day 5 on average; this is very similar to the present study (placebo group in the former study at day 7).

Comparison of the new data with the placebo-controlled study mentioned aboveCitation23 leads to the same conclusion: this treatment results in a faster recovery from a common cold. The time to improvement of the colds in both studies was similar although the daily dose was higher with the compact dosage form used in this study (48 mg extract per day) than in the previous study (28.8 mg/d)Citation23. The study settings in these two approaches differed, namely a pharmacy-based observation in real life versus a practitioner-controlled investigation in a clinical trial. Thus, an indirect dose-response assessment across these studies is not reliable. However, this aspect was directly investigated in another placebo-controlled studyCitation25, showing a dose-response relationship for the same native extract. Since a “runny nose” is a main symptom of a cold, the total number of facial tissues used throughout the clinical duration of a cold was the primary efficacy parameter. It differed significantly between groups as early as day 2. This effect was dose dependent with preference for the higher dose of 57.6 mg per day, which is even higher than the dose used by the patients in the present study. In the study presented here, the course of the disease was also mainly determined by rhinitis. The rhinitis score, with its single symptom “runny nose” in this study, showed response rates in the same range as the other scores and symptoms. This confirms – vice versa – the validity of the parameter “tissue use” as a surrogate measure of the total symptom complex. The dosage of this medication is within the range of the two placebo-controlled trials mentioned above, and its efficacy and safety were affirmed by the present results.

Even if colds heal spontaneously, a quick improvement in symptoms is desirable because a cold interferes with the patient’s daily activities, including work or school performance. In the current study, the turning point of the symptoms from more severe to less severe during the course of the illness was documented on day 3.9 of treatment with this herbal remedy. As previously describedCitation23, optimal efficacy in this study was also shown in patients who started treatment earlier in the course of their cold. A significantly faster recovery rate resulted if the cold was no more than 3 days old (p = .049; HR = 0.814). This accords with former publications on products containing echinacea preparations. Their immunomodulatory activity is most effective with early initiation of treatmentCitation23,Citation29,Citation30.

There is a lively discussion about whether there is solid evidence that echinacea products effectively treat or prevent the common cold; some groups argue that the evidence is poorCitation10,Citation11,Citation31. This general assessment suffers from the diversity of echinacea preparations tested in clinical trials. However, the product investigated here is not made from echinacea alone, but from a mixture of echinacea, baptisia and thuja. Each of these herbal substances contributes to the overall effectCitation32. Immunological effects of the contained substances were verified in individual test systemsCitation33. Activation of macrophages, induction of IgM-titer elevation and enhancement of cytokine production are promoted by this composition of different herbal species and help trigger the infection defenseCitation32. Because enhancement of the non-specific immune response leads to a faster recovery, the immunomodulating herbal remedy is able to improve a patient’s discomfort in a short period of time, probably leading to less absenteeism from work or school, or a faster improvement of impaired performance at work or school.

The prevalence of co-medication for a cold is high under natural circumstances. This might put into question the validity of the results, but represents a real-life situation. Nonetheless, we were able to analyze any impact of co-treatment because of the high number of participants. Co-medication of the study medication with products for cold symptoms was not associated with a more rapid but rather a slower improvement of the cold in comparison to taking the study medication without such co-medication. However, severe symptoms of bronchitis at baseline were associated with concomitant cough medication, so a treatment allocation bias may, at least partially, account for the slower recovery of these co-medicated patients. Cough and pain in the chest are symptoms that contribute significantly to the feeling that a cold is serious. Several studies have shown that the immunostimulating phytomedicine as add-on therapy improves recoveryCitation34–38. Applied concomitantly to an antibiotic for chronic bronchitis, the lung function improved significantly faster compared to the antibiotic combined with a placeboCitation38.

Patients from age 12 on as well as adults and elderly benefit to the same extent from using this herbal medicinal product during a cold. Thus, long-lasting knowledge regarding efficacy and safety of this native substance gained in adults from placebo-controlled studies can be extrapolated to younger patients from 12 years of age and older.

The tolerability was “good or very good” in 98% of the patients. Adverse drug reactions were rare and within the expected spectrum. Thus, no new conclusions regarding the risk–benefit balance for individual patients or risk groups arose from this study.

Conclusion

The benefit–risk assessment of this herbal extract clearly remains positive. This non-interventional study accords with and shows transferability of the results of previous placebo-controlled studies with this unique extract in a real-life setting. The total body of evidence from clinical studies confirms the good to very good efficacy, tolerability and high patient satisfaction of this phytomedicine on common cold symptoms. An early start of therapy with this extract is associated with a faster improvement of the common cold.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other relationships

H.H.H.v.Z., P.N., B.N., J.C.K., N.B. and K.U.N. have disclosed that they are employees of Schaper & Brümmer GmbH & Co KG, Germany, the sponsor of this study. A.H. and J.S. have disclosed that they are employees of the contract research organization for this study. However, all authors declare that these employments have not had any impact on any of the contributions to this manuscript. CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

H.H.H.v.Z.: concept, design and project management of this study; authorship of parts of the manuscript; P.N.: scientific advice for this study; authorship of parts of the manuscript; B.N.: scientific advice and pharmacovigilance for this study; authorship of parts of the manuscript; J.C.K.: scientific advice for this study; proofreading of the manuscript; N.B.: management of the contact persons for the study sites; A.H.: statistical analyses for this study and one of the authors of the study report; J.S.: senior qualified biometrician for this study and one of the authors of the study report; K.U.N.: senior scientific advice for this study; proofreading of the manuscript.

Imputation Strategy

Download PDF (169 KB)Final Report

Download PDF (262.4 KB)Gebrauchsinformation: Information für den Anwender

Download PDF (122.4 KB)STROBE Statement - Checklist of items that should be included in reports of cohort studies

Download PDF (180.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participating pharmacies. Furthermore, the authors thank the field staff for their comprehensive support.

Note

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Esberitox is a registered trade name of Schaper & Brümmer GmbH & Co. KG, Salzgitter, Germany

References

- Heikkinen T, Järvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361:51–59.

- Makela MJ, Puhakka T, Ruuskanen O, et al. Viruses and bacteria in the etiology of the common cold. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:539–542.

- Papadopoulos NG, Megremis S, Kitsioulis NA, et al. Promising approaches for the treatment and prevention of viral respiratory illnesses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:921–932.

- Healthcare Marketing. Selbstmedikation mit OTC-Produkten beliebter als Arztbesuch [Self-medication with OTC products more popular than doctor’s visit] [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2018 Dec]. Available from: http://www.healthcaremarketing.eu/unternehmen/detail.php?nr=33531

- Barrett B. Medicinal properties of Echinacea: a critical review. Phytomedicine. 2003;10:66–86.

- Bauer R, Remiger P, Jurcic K, et al. Beeinflussung der Phagozytose-Aktivität durch Echinacea-Extrakte [Effect of extracts of Echinacea on phagocytic activity]. Z Phytother. 1989;10:43–48.

- Bodinet C, Mentel R, Wegner U, et al. Effect of oral application of an immunomodulating plant extract on Influenza virus type A infection in mice. Planta Med. 2002;68:896–900.

- Sullivan AM, Laba JG, Moore JA, et al. Echinacea-induced macrophage activation. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2008;30:553–574.

- Gulledge TV, Collette NM, Mackey E, et al. Mast cell degranulation and calcium influx are inhibited by an Echinacea purpurea extract and the alkylamide dodeca-2E,4E-dienoic acid isobutylamide. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;212:166–174.

- Linde K, Barrett B, Wölkart K, et al. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;42.

- Assessment report on Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench, radix [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Dec]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Herbal_-_HMPC_assessment_report/2017/08/WC500233235.pdf

- Wagner L, Cramer H, Klose P, et al. Herbal medicine for cough: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Med Res. 2015;22:359–368.

- Aarland RC, Banuelos-Hernandez AE, Fragoso-Serrano M, et al. Studies on phytochemical, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, hypoglycaemic and antiproliferative activities of Echinacea purpurea and Echinacea angustifolia extracts. Pharm Biol. 2017;55:649–656.

- Alves LDS, Figueirêdo CBM, Silva C, et al. Thuja ossidenatlis L. (Curpressaceae): review of botanical, phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological aspects. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2014;5:1163–1177.

- Bodinet C, Volk R, editors. Oral application of Thuja occidentalis enhances immune parameters in rats and immunosupressed mice. 7th Joint Meeting of GA, AFERP, PSI & SIF; 2008; Athens, Greece.

- Dubey S. Antioxidant activities of Thuja occidentalis Linn. AJPCR. 2009;2:73–76.

- Silva IS, Nicolau LAD, Sousa FBM, et al. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory potential of aqueous extract and polysaccharide fraction of Thuja occidentalis Linn. in mice. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;105:1105–1116.

- Sunila ES, Hamsa TP, Kuttan G. Effect of Thuja occidentalis and its polysaccharide on cell-mediated immune responses and cytokine levels of metastatic tumor-bearing animals. Pharm Biol. 2011;49:1065–1073.

- Naser B, Bodinet C, Tegtmeier M, et al. Thuja occidentalis (Arbor vitae): a review of its pharmaceutical, pharmacological and clinical properties. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:69–78.

- Classen B, Thude S, Blaschek W, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of arabinogalactan-proteins from Baptisia and Echinacea. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:688–694.

- Banerji P, Banerji P, Das GC, et al. Efficacy of Baptisia tinctoria in the treatment of typhoid: its possible role in inducing antibody formation. J Complement Integr Med. 2012;9:Article 15.

- Schleinitz H, Staesche K, et al. Baptisia. In: Blaschek W, Hilgenfeldt U, Holzgrabe U, editors. Hagers Enzyklopädie der Arzneistoffe und Drogen [Hager’s Encyclopedia of Meds and Drugs]. Springer-Verlag; 2016 [HN: 20106002015].

- Henneicke-von Zepelin H, Hentschel C, Schnitker J, et al. Efficacy and safety of a fixed combination phytomedicine in the treatment of the common cold (acute viral respiratory tract infection): results of a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, multicentre study. Curr Med Res Opin. 1999;15:214–227.

- Reitz H-D. H. H. Immunmodulatoren mit pflanzlichen Wirkstoffen- 2. Teil: eine wissenschaftliche Studie am Beispiel Esberitox N [Immuno-modulators with phytotherapeutic agents - part 2: a scientific study with Esberitox N]. Notabene Medici. 1990;20:362–366.

- Naser B, Lund B, Henneicke-von Zepelin HH, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical dose–response trial of an extract of Baptisia, Echinacea and Thuja for the treatment of patients with common cold. Phytomedicine. 2005;12:715–722.

- Brinkeborn RM, Shah DV, Degenring FH. Echinaforce and other Echinacea fresh plant preparations in the treatment of the common cold. A randomized, placebo controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Phytomedicine. 1999;6:1–6.

- Macknin ML, Piedmonte M, Calendine C, et al. Zinc gluconate lozenges for treating the common cold in children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;279:1962–1967.

- Yale SH, Liu K. Echinacea purpurea therapy for the treatment of the common cold: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1237–1241.

- Gwaltney JM. Viral respiratory infection therapy: historical perspectives and current trials. Am J Med. 2002;112:33–41S.

- Barrett B, Vohmann M, Calabrese C. Echinacea for upper respiratory infection. J Fam Pract. 1999;48:628–635.

- Karsch-Völk M, Barrett B, Kiefer D, et al. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:94.

- Teuscher E, Bodinet C, Lindequist U, et al. Untersuchungen zu Wirksubstanzen pflanzlicher Immunstimulanzien und ihrer Wirkungsweise bei peroraler Applikation [Investigation of active substances in herbal immunostimulants and their mode of action after peroral administration]. Z Phytother. 2004;25:11–20.

- Bodinet K. Immunpharmakologische Untersuchungen an einem pflanzlichen Immunmodulator [Immunpharmacological examinations on a plant immunomodulator]. Greifswald: Universität Greifswald; 1999.

- von Blumröder WO. Angina lacunaris – Eine Untersuchung zum Thema “Steigerung der körpereigenen Abwehr”. Z Allg Med. 1985;61:271–273.

- Freitag U. Reduzierte Krankheitsdauer bei Pertussis durch unspezifisches Immunstimulans [Shortened duration of disease due to a non-specific immunostimulant in pertussis]. Der Kinderarzt. 1984;15:1068–1071.

- Stolze H, Forth H. Eine Antibiotikabehandlung kann durch zusätzliche Immunstimulierung optimiert werden [A treatment with antibiotics can be optimized by additional immunostimulation]. Der Kassenarzt. 1983;23:43–48.

- Zimmer M. Gezielte konservative Therapie der akuten Sinusitis in der HNO-Praxis [Special conservative therapy of acute sinusitis in the ENT practice]. Therapiewoche. 1985;35:4024–4028.

- Hauke W, Köhler G, Henneicke-von Zepelin HH, et al. Esberitox N as supportive therapy when providing standard antibiotic treatment in subjects with a severe bacterial infection (acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis). Chemotherapy. 2002;48:259–266.