Abstract

Background: Biologics used to treat ulcerative colitis (UC) may lose their effect over time, requiring patients to undergo dose escalation or treatment switching, and systematic literature reviews of real-world evidence on these topics are lacking.

Aim: To summarize the occurrence and outcomes of dose escalation and treatment switching in UC patients in real-world evidence.

Methods: Studies were searched through MEDLINE, MEDLINE IN PROCESS, Embase and Cochrane (2006–2017) as well as proceedings from three major scientific meetings.

Results: In total, 41 studies were included in the review among which 35 covered dose escalation and 12 covered treatment switching of biologics. Tumor necrosis factor antagonist (anti-TNF) escalation for all patients included at induction ranged from 5% (6 months) to 50% (median 0.67 years) and 15.2% to 70.8% (8 weeks) for anti-TNF induction responders. Mean/median time to dose escalation on anti-TNF ranged from 1.84 to 11 months. The most common switching pattern, infliximab → adalimumab, occurred in 3.8% (median 5.6 years) to 25.5% (mean 3.3 years) of patients.

Conclusions: Dose escalation and treatment switching of biologics may be considered as indicators of suboptimal therapy suggesting a lack of long-term remission and response under current therapies.

Introduction

Biologic therapies have significantly improved the management of patients affected by ulcerative colitis (UC), a chronic disease characterized by a diffuse inflammation of the rectal and colonic mucosa and delineated by periods of remissions and relapses. Due to the nature of the disease, patients are required to switch treatments, undergo dose escalation or ultimately undergo surgery which occurs at a rate of 3%–17% in adultsCitation1.

The use of biologics such as tumor necrosis factor antagonists (anti-TNFs) or anti-integrins is recommended in moderate to severe UC patients who do not respond to conventional treatments including immunosuppressants by the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) and the American Gastroenterological AssociationCitation2–4.

As a considerable proportion of patients do not respond to induction therapy (primary failure) or will lose response over time (secondary failure)Citation5, the third European consensus on the diagnosis and management of UC suggests maintaining a patient in remission via either a dose escalation of oral/rectal aminosalicylates, or an addition of thiopurine or biologic treatment (anti-TNF or vedolizumab) (ECCO statement 12 D)Citation3.

It is estimated that 5–50% of ulcerative colitis (UC) patients require dose escalation during the course of their treatment according to NICE and the UK Inflammatory Bowel Disease AuditCitation6–8. A multinational chart review in Europe and Canada reported that 29.7% of anti-TNF initiators and 17.1% of anti-TNF switchers affected with UC required dose escalationCitation9, which underlines the loss of response in UC patients under induction or maintenance or intolerance to treatment. Treatment switching occurs in around a third of inflammatory bowel disease patients receiving anti-TNF who do not respond to therapy (primary failure) and a large portion of these patients will lose response (secondary failure) or be intolerant to the therapy, which is why research is needed to understand the extent to which it occurs and what the true effectiveness of biologics is in clinical practiceCitation10.

Dose escalation is usually studied in clinical trials assessing the efficacy of biologics (ULTRA1, ULTRA2 and Suzuki et al. for adalimumabCitation11; PURSUIT-SC and PURSUIT-Maintenance for golimumab; and ACT1, ACT2, Probert et al.Citation13 and UC-SUCCESS for infliximabCitation10; all clinical study results were accessed via Clinicaltrials.gov), which may not be reflective of the true efficacy in routine clinical practiceCitation11. Therefore, the aim of this systematic literature review is to assess the evidence on dose escalation and treatment switching in UC patients that occur in “real life” practice in primary and secondary non-responders or intolerant patients to have a better understanding of the real world patients live inCitation12–14.

The objectives of our research were the following:

Primary objective: to investigate the rates and outcomes of dose escalation and treatment switching in UC adult patients under biologic therapy in real life/clinical practice

Secondary objectives (related to dose escalation):

To quantify rates of response and remission, time to loss of response, rates of treatment de-escalation and adverse events after dose escalation

To identify the dosing regimens under dose escalation and time to dose escalation

To assess potential predictors that have been identified to play a role in dose escalation

Secondary objectives (related to treatment switching): to quantify the rates of response and remission and adverse events after treatment switching.

Methods

Dose escalation and treatment switching definitions

Dose escalation consists of a decrease in the interval between doses and/or an increase in the maintenance doseCitation15.

Treatment switching consists of switching from one therapy to a therapy of the same drug class or different drug class in order to treat a specific condition.

De-escalation is defined as an increase in the interval of administration or a decrease in the dosage strength of any treatment.

Literature search

The protocol for this review was not registered. The first phase of the literature search was conducted to establish the criteria to select relevant articles, including eligible study designs, patients, interventions and acceptable outcomes. Once the criteria were established and approved (see Study selection), a search strategy was developed to collect data on dose escalation and treatment switching in adult UC patients.

A systematic literature review was conducted on 22 May 2017 via Embase, MEDLINE (through Embase) and on 7 June 2017 via the Cochrane Library. The databases were searched for all studies reporting outcomes on dose escalation in daily clinical practice, time to dose escalation, clinical response/remission after dose escalation and predictors of dose escalation using the medical subject headings “ulcerative colitis”/exp OR “ulcerative colitis” OR “inflammatory bowel disease”/exp OR “inflammatory bowel disease” OR “ibd”. Geographical limitations were not set.

A hand search was additionally performed in order to identify all studies of interest published by important European clinical societies, such as United European Gastroenterology Week (UEGW), European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO) and Digestive Disease Week (DDW). All studies obtained were then cross referenced.

The searches were restricted to capture literature published within the time frame of January 2006 until May and June 2017 to mark the uptake of anti-TNFs in the treatment regimen of ulcerative colitis (approval of infliximab in ulcerative colitis granted in September 2005 by the FDA and EMA in 2009).

Two authors independently examined titles and abstracts. All discrepancies were solved by discussion. If no agreement was found, a third reviewer was involved in the discussion.

Study selection

For inclusion into the review, studies needed to fulfill the following criteria: (i) adult patients with a diagnosis of an active moderate to severe UC who were treated with (ii) biologic therapies including adalimumab, golimumab, infliximab and vedolizumab and enrolled in (iii) observational or real-world evidence studies.

Population: adult patients with ulcerative colitis, treated with biologic therapy who required a de-/escalation or required a switch in therapy.

Interventions: adalimumab, golimumab, infliximab and vedolizumab in all available doses included in observational studies as a monotherapy or in combination with background therapy such as purine antimetabolites and in all possible administration routes.

Study type: prospective and retrospective observational studies, cohort and database studies as well as case studies were included. Systematic literature reviews that included these types of studies were also included for cross-referencing.

Randomized controlled trials and clinical trials were excluded. Publications that were not written in English were also excluded.

Outcomes: Rate of patients undergoing dose escalation or switching; time to dose escalation or switching; time spent on escalated dose or therapy to which patients were switched to; average dose to which patients were escalated to or therapy to which patients were switched to; rates of dose de-escalation after initial dose escalation; clinical outcomes of patients who underwent dose escalation or treatment switching; rate of adverse events as a result of dose escalation and switching; predictors of dose escalation.

Articles were excluded if they were based on a different intervention (i.e. surgery, pharmacotherapy other than biologics), different endpoint (i.e. clinical analysis, budget impact analysis, cost assessments), or a different indication (Crohn’s disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, etc.).

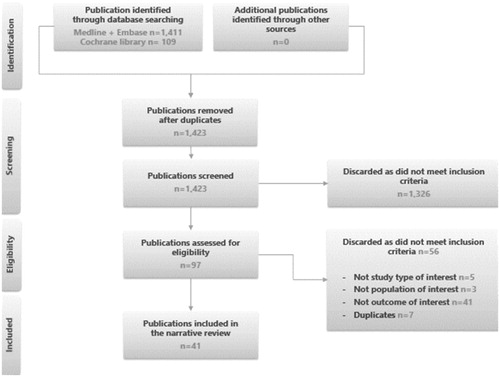

The selected articles that met the inclusion criteria in accordance with the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study type (PICOS) scheme, were included in this review. The records were selected in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and can be seen in .

Data extraction and analysis

Data from eligible studies were collected. Data extraction was carried out by three researchers and quality control has been done for at least 20% of extracted data, as defined in the study protocol.

Results were then tabulated and analyzed using descriptive statistics. All of the fields regarding the outcomes of interest (see PICOS in Study selection) were extracted if reported.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported for the study outcomes for all patients and for each of the dosing cohorts. Univariate, bivariate and multivariate analyses were not conducted to assess the association of baseline characteristics with cohorts or patient characteristics with dose escalation.

Results

Literature search results

After having applied a search strategy for dose escalation and treatment switching as described, 41 studies were identified amongst which 20 articles and 21 abstracts were identified, as shown in . Regarding the geographical scope of these studies, 24 originated from Europe, 7 from the USA, 2 from Canada, 3 from Japan, 1 from Israel and 4 that did not report a specific country. Data largely emanated from retrospective data (80%) compared to prospective studies (20%), as shown in .

Table 1. Characteristics of identified studies.

The time of patient follow-up across studies varied between 0.46 years and a median of 5.16 years across studies. Dose escalation and treatment switching were covered by respectively 35 and 12 studies.

Amongst the outcomes of interest in dose escalation, descriptive statistics were reported in all studies; however, effectiveness outcomes after dose escalation and/or treatment switching were reported only in respectively 11 and 2 studies. Predictors of dose escalation were only reported in 3 studies.

Dose escalation

Dose escalation in daily clinical practice

Dose escalation of moderate to severe UC patients was reported in 35 out of 41 studies identified through the predefined PICOS scheme and was reported for anti-TNF, IFX, adalimumab (ADA), golimumab (GOL) and vedolizumab (VDZ) for different types of patient populations (all patients included at induction, induction responders only, primary or secondary non-responders).

The rate of escalation in all anti-TNF patients included at induction ranged from 5% in 380 patients at 6 monthsCitation48 to 50% in 54 patients at a median of 0.67 yearsCitation30, while escalation in anti-TNF induction responders ranged from 15.2% in 257 patientsCitation26 to 70.8% in 24 patients at 8 weeksCitation55. Patel et al. conducted a study in the USA on 1669 anti-TNF naïve UC patients and reported an increased rate of dose escalation over time, 16% at 6 months, 28% at 12 months, 40% at 24 months and 44% at 36 monthsCitation44.

The rate of dose escalation of IFX in all anti-TNF naive patients included at induction was reported in seven studies and ranged from 6% in 434 patients at 6 monthsCitation48 to 48.1% in 54 patients at a median of 4 monthsCitation23.

For induction responders of IFX, dose escalation was reported in seven studies and ranged from 15.2% in 257 patientsCitation26 (time to dose escalation was not reported by Cappello et al.Citation26) to 70.8% in 24 patients at 8 weeksCitation55. For IFX patients in mucosal healing at maintenance and in response or remission at induction, dose escalation occurred in respectively 15% of 40 patients within the second yearCitation21 and 36.8% of 144 at 9 monthsCitation33.

Dose escalation of IFX occurred at baseline in 157 patients with primary or secondary loss of response at a median of 6 monthsCitation31 and in 79 patients with a secondary loss of response at a median of 9.2 monthsCitation52.

Dose escalation of ADA was reported in 14 studies for either anti-TNF naïve and/or anti-TNF experienced patients.

Dose escalation of ADA in anti-TNF naïve patients included at induction was reported in four studies and ranged from 5% in 380 patients at 6 monthsCitation48 to 45.9% in 37 patients at a median of 5 monthsCitation23. Whereas, dose escalation of induction responders of anti-TNF naïve patients under ADA was reported in three studies and occurred in 17.6% of 68 patients at a median of 6 monthsCitation53 and 46.6% in 58 patients at 2.75 yearsCitation35.

Dose escalation of ADA among anti-TNF experienced patients who responded to induction occurred in 55.2% of 116 patients at a median of 5 monthsCitation53.

Dose escalation of ADA in both anti-TNF naïve and anti-TNF experienced patients included at induction was reported in five studies and ranged from 25% in 52 patients at 12 monthsCitation37 to 50% in 54 patients at a median of 0.67 yearsCitation30. ADA escalation of induction responders in both anti-TNF naïve and anti-TNF experienced occurred in 43.5% of 191 patients at a median of 4.57 monthsCitation24.

For induction responders of ADA who were either anti-TNF naïve or anti-TNF experienced, dose escalation occurred for 43.5% of 191 patients at a median time of 4.57 months.

Dose escalation under GOL for everyone included at induction occurred in 22% of 142 patients at a median of 5 monthsCitation50 and in 3.6% of 136 induction responders after 3 yearsCitation25.

Dose escalation under VDZ after failure (defined as inadequate response to the drug) of anti-TNF occurred in 20% of 15 patients (time to dose escalation was not reported by Ladd et al.Citation40) in response or remission at maintenanceCitation40 and in 47.1% of 121 induction responders at 1 yearCitation18. Dose escalation under VDZ increased over time in 121 induction responders as such: 9.9%, 29.8%, 43% and 47.1% at respectively 1.4 months, 3.2 months, 5 months and 1 yearCitation18.

The dose escalation regimen was only reported in 14 studies out of which seven were appointed to a dose escalation under IFX, five to a dose escalation under ADA, one to a dose escalation under GOL and two to a dose escalation under VDZ.

IFX initial and escalated regimen was commonly reported as 5 mg/kg q8w and 10 mg/kg q8w or 5 mg/kg q4–6w respectively in seven studiesCitation28,Citation30,Citation33,Citation34,Citation45,Citation52,Citation55. The most frequent initial and escalated regimen for ADA was 40 mg or 80 mg q2w and 40 mg q1w respectivelyCitation16,Citation20,Citation29,Citation36,Citation37. Only one study reported the initial and escalated regimen of GOL which was 50 or 100 mg q4wk and 100 or 200 mg q4wk respectivelyCitation50. VDZ initial and escalated regimen in two studies was 300mq q8w and 300mq q4w respectivelyCitation18,Citation40.

Detailed information concerning the rate of dose escalation, sample size and regimen for each study are shown in .

Table 2. Dose escalation outcomes in daily practice.

Response and remission after dose escalation

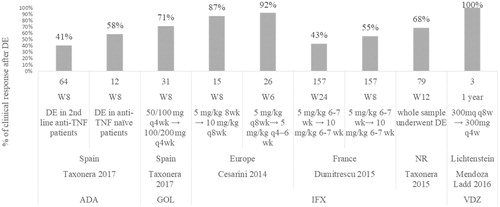

Results reporting clinical response and clinical remission after dose escalation found for ADA, GOL, IFX and VDZ are shown in and Citation3. In a study in which less than 30 anti-TNF naïve patients underwent IFX dose escalation, clinical response was achieved in 92.30% of 26 patients at week 6Citation28 and 86.70% of 15 patients at week 8Citation28. In two studies in which more than 70 anti-TNF naïve patients underwent IFX dose escalation, clinical response was achieved in 55% of 157 patients at week 8Citation31, 68.40% of 79 patients at week 12Citation52 and 43% of 157 patients at week 24Citation31 ().

Figure 2. Percentage of patients with clinical response after dose escalation. Taxonera 2017 (ADA)Citation53, Taxonera 2017 (GOL)Citation50 , Cesarini 2014 (IFX)Citation28, Dumitrescu 2015 (IFX)Citation31, Taxonera 2015 (IFX)Citation52, Ladd 2016 (VDZ)Citation40.

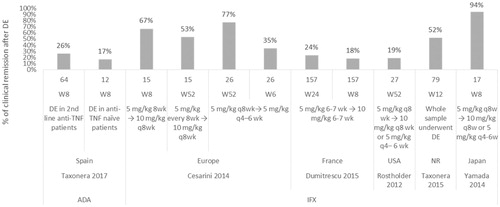

In two studies in which less than 30 patients dose escalated, clinical remission was achieved in 34.6% of 26 patients at week 6Citation28 and 77% of 26 patients at week 52Citation28 after a shortened dose interval. After a doubled dose IFX, clinical remission was achieved in 66.70% of 15 patients at week 8Citation28 and in 19% of 27 patientsCitation45 and 53% of 15 patients at week 52Citation28. In two studies in which more than 70 patients dose escalated, clinical remission was achieved in 18% of 157 patients at week 8 after a doubled dose of IFXCitation31, in 51.90% of 79 patients at week 12Citation52, and in 24% of 157 patients at week 52 after a doubled dose of IFXCitation31 ().

Figure 3. Percentage of patients in clinical remission after dose escalation. Taxonera 2017 (ADA)Citation53, Cesarini 2014 (IFX)Citation28, Dumitrescu 2015 (IFX)Citation31, Taxonera 2015 (IFX)Citation52, Rostholder 2012 (IFX)Citation45, Yamada 2014 (IFX)Citation55.

Taxonera et al.Citation53 is the only publication reporting the achieved clinical response and remission after dose escalation for ADA. Clinical response after ADA escalation at week 8 was achieved in 58.30% of 12 anti-TNF naïve patients compared to 40.6% of 64 anti-TNF experienced patients. Clinical remission at week 8 after ADA dose escalation was achieved by 26.30% of 12 anti-TNF patients compared to 16.66% of 64 the anti-TNF experienced patients.

Time to dose escalation

Mean/median time to dose escalation was reported in 13 out of 41 publications for IFX and ADA, and respectively ranged from 4 monthsCitation23 to 11 monthsCitation45 and from 1.84 monthsCitation16 to 6 monthsCitation53 as shown in . Time to dose escalation for patients treated with GOL was reported by Taxonera et al.Citation50 as a median of 5 months.

Time to dose escalation for VDZ was not provided.

Time to loss of response after dose escalation

Taxonera et al.Citation52,Citation53 are the only two publications that define the percentage of patients that lose response after dose escalation.

Median time to loss of response after dose escalation was assessed for IFX and ADA at 15 (IQR 8–26)Citation52 and 17 (IQR 9–43)Citation53 months, respectively. Taxonera et al. reported that among IFX and ADA dose escalators, 33% of IFX patients experienced loss of response at 1.25 years and 23.37% of ADA dose escalators experienced loss of response at 1.91 years.

Treatment de-escalation

Although de-escalation is not referred to as being effective in treating patients in order to achieve or maintain clinical response and remission, it was reported in eight out of 35 dose escalation studies.

Four studies reported the proportion of dose de-escalation under IFX treated patientsCitation28,Citation31,Citation33,Citation52, which ranged from 15% of 79 dose escalated patients at a median time to dose de-escalation of 6 monthsCitation52 to 51% of 41 dose escalated patients at a mean time to dose de-escalation of 13.6 monthsCitation28. In the totality of cases, patients were de-escalated to a regimen of 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks.

Dose de-escalation under ADA was reported by four studies. In anti-TNF naïve patients only, median time to dose de-escalation was 162 days in 191 dose escalated patientsCitation47. In anti-TNF naïve and experienced patients combined, median time to dose de-escalation was between 21 days in 83 dose escalated patientsCitation24 and 5 months in 31 dose escalated patientsCitation20.

Adverse events after dose escalation

Adverse events after dose escalation are not extensively monitored and only five studies reported adverse events data following an anti-TNF dose escalation.

Iborra et al. reported adverse events in 6.5% of 93 patients who dose escalated under ADACitation38, whilst four studies reported adverse events which ranged from 8% to 14.30% of respectively 157 and 53 patients who dose escalated under IFXCitation31,Citation34,Citation51,Citation52.

Detailed information on the type of adverse event after dose escalation was only reported in one study by Dumitrescu et al.Citation31. The highest rate of adverse event was attributed to acute or delayed infusion reactions which affected 6% of IFX dose escalated patients.

Predictors of dose escalation

Predictors of dose escalation are not well documented and were only reported in three papers out of 35 studies on dose escalation (Fernández-Salazar et al.Citation33, Oussalah et al.Citation43, Taxonera et al.Citation51).

Three factors were found to significantly predict and enhance the likeliness of a dose escalation: initiating IFX in acute severe colitis patients (HR = 2.75, p = .01)Citation43, having ulcerative colitis compared with Crohn’s disease (HR = 2.73, p = .007)Citation51 and using immunomodulator therapy before a treatment with IFX (HR = 3.999, p = .008)Citation33.

None of the studies identified above reported disease duration and metabolic concentrations (i.e. iron binding capacity) as predictors of dose escalation.

Treatment switching

Treatment switching in daily clinical practice

Switching patterns ranged between 1% in 380 patients at 6 monthsCitation48 to 26% in 538 patients at 2 yearsCitation39 in six studies comprising more than 200 patients ().

Table 3. Treatment switching in daily clinical practice.

The switching pattern IFX → ADACitation17,Citation19,Citation23,Citation29,Citation49 was reported in five studies and ranged between 3.8% at a median time of 5.16 years to 25.5% at a mean of 3.3 years in respectively 26 and 98 patients ().

Another study by Baki et al.Citation23 with a median follow-up period of 2.5 years reported a switch from ADA → IFX in 6.94% of 72 UC patients, indicating its very low use in treatment of UC in contrast to the switching scheme reported above.

Six switching patterns in UC were tied to a switch from or to an anti-TNF in seven studies: 1 anti-TNF → ADACitation56, 1 anti-TNF → IFXCitation56, 3 IFX → anti-TNFCitation35,Citation42,Citation48, 2 ADA → anti-TNFCitation35,Citation48, 2 anti-TNF→ anti-TNFCitation39,Citation44 and 1 anti-TNF→ anti-TNF or VDZCitation54. As these switching patterns were reported in studies comprising different sample sizes and time of assessments or switching, no sub-analysis could be performed.

Two studies by Patel et al.Citation44 and Sandborn et al.Citation48 reported the proportion of switching over time. In a sample size of 1699 patients, switching from an anti-TNF→ anti-TNF or VDZ occurred in 6% of UC patients at 6 months and 11% of UC patients at 36 monthsCitation44. Switching from ADA → anti-TNF occurred in 1% of UC patients at 6 months, to 4% of patients at 12 months and 4% of patients at 18 months. Switching from IFX→anti-TNF occurred in 1.5% of patients at 6 months, to 2% patients at 12 months and 3% patients at 18 monthsCitation48.

Data on the time from loss of response after switching was not reported, as well as the time spent on therapy before switching.

The cause of switching was not reported or specified in the majority of the studies; however, three studies reported a switching due to loss of responseCitation23,Citation47,Citation49, and two studies reported a switching due to adverse events with IFXCitation23,Citation29 or ADACitation23.

Response and remission after treatment switching

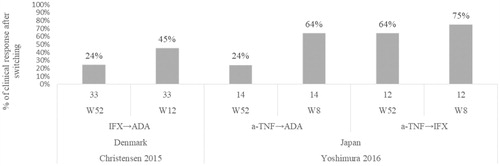

Clinical response and remission achieved after switching were reported in respectively one study by Christensen et al.Citation29 and two studies Christensen et al.Citation29 and Yoshimura et al.Citation56, indicating weak evidence on this topic.

Following a whole sample size switch of 33 patients from IFX → ADA in Christensen et al.Citation29 during a median of 0.62 years, the proportion of patients in clinical response remarkably decreased from 45% at 12 weeks to 24% after 1 year, showing a consecutive loss of response to ADA ().

Figure 4. Percentage of patients with clinical response after switching Christensen 2015Citation29, Yoshimura 2016Citation56.

Yoshimura et al.Citation56 found that the long term response at week 52 after switching was significantly lower in the ADA sub-group with prior exposure to anti-TNF compared with the IFX group (24% vs. 64%) ().

Rates of patients in clinical remission a year after switching were reported in two studiesCitation29,Citation56. Yoshimura et al. reported that 85.7% of 44 patients who switched from anti-TNF to IFX and 37.5% (9/14) of 14 patients who switched from anti-TNF to ADA had maintained remissionCitation56. Christensen et al. reported that 18% of 33 patients who switched from IFX to ADA were in clinical remissionCitation29.

Adverse events after treatment switching

Only one study by Christensen et al. with a median follow-up duration of 0.62 years reported the occurrence of adverse events following switching. Two patients amongst 33 patients who switched from IFX → ADA experienced an allergic reaction to ADA after a yearCitation29.

Discussion

The objective of this systematic literature review is to understand the evidence on dose escalation in a real-world setting and its impact on patients’ outcomes. However, as the overall incidence of UC is reported as 1.2–20.3 cases per 100,000 persons per year, real-world evidence literature on dose escalation and treatment switching in ulcerative colitis is scarce, with a total number of articles amounting to respectively 34 and 12.

The average rate of dose escalation within 1 year across anti-TNF and anti-integrin therapy, irrespective of disease duration, sample size and follow-up study duration, is equivalent to 36%. This finding is consistent with a recent systematic literature review on dose escalation in Crohn’s disease by Einarson et al.Citation15 which reported that approximately 30% of patients required dose escalation during the first year of treatment.

Similarly, time to dose escalation of IFX in UC patients was approximately 7.6 months, which is consistent with the time to dose escalation of IFX patients in Crohn’s disease according to the findings of Einarson et al. There is very limited evidence on time to loss of response after dose escalation in UC patients, which was only reported by two studiesCitation52,Citation53 and indicates the failure (defined as complete loss of response, as judged by the treating physician) of ADA and IFX at 17 and 15 months respectively.

Solid comparison on the superiority of IFX, VDZ or ADA on clinical response and remission in a real-world setting is not possible, as the heterogeneity in sample size, patient population and time points at which clinical response and remission were reported differ and the number of publications that report these outcomes is low. The long-term outcome of dose escalation is not widely understood and needs to be further investigated.

Adverse events after dose escalation are poorly monitored, but anti-TNFs are not without risk, the rate of adverse events ranged between 6% and 14.3% in an average sample size comprising more than 50 patients. This is consistent with the literature as a recent multinational chart review reported that, in general terms, one in five UC patients experienced adverse events with their anti-TNF treatmentCitation9.

Although anti-TNF failure has been identified as a predictor of dose escalation in patients treated with a second biologic, solid evidence on predictors of dose escalation in ulcerative colitis patients is lacking. Taxonera et al. have shown that anti-TNF failure in UC is a predictor of dose escalation and colectomy. Anti-TNF-naïve patients had significantly lower adjusted rates of ADA dose escalation and need for colectomy compared to anti-TNF failure patients (HR 0.26; p < .004)Citation53.

There are several potential limitations that arise from our review, therefore this review should be considered as a qualitative synthesis of the findings.

The variety of the patient selection across the 41 studies selected (e.g. induction responders versus secondary loss of response patients) as well as the lack of information on baseline characteristics stratified by population subgroup (only provided in four studies) and disease activity index (only reported in 12 studies) prevents the conducting of a robust and conclusive statistical analysis. Moreover, there is a lack of a harmonized definition on clinical remission in ulcerative colitis patients, with definitions varying across 10 studies. According to the ECCO, there is no fully validated definition of disease activity and clinical remission in ulcerative colitis, but a consensus on defining remission according to a stool frequency of ≤3/day with no bleeding and no mucosal lesions at endoscopyCitation58.

The variety of patient follow-up time, sample size and time of assessment makes it also difficult to compare and interpret the proportion of dose escalation and treatment switching across different therapies and lines of treatments as well as to make any correlations between the use of prior anti-TNF medication and the time to dose escalation or treatment switching.

Data reporting, particularly in abstracts, was often incomplete and therefore patient characteristics, time to escalation and treatment switching outcomes were very scarcely documented.

Dose escalation in ulcerative colitis patients is usually reflective of the clinical unmet need of available treatments; however, data are still insufficient to understand the outcomes of dose escalation. Our findings strongly suggest a lack of long term remission and response with current biologic therapies in ulcerative colitis and the need for new and more effective products for patients, as the occurrence of switching and dose escalation particularly may be considered indicators of suboptimal therapyCitation44.

Discrepancy in the findings and lack of data reported on biologics used before or after switching may reflect an absence of good standardized clinical practice regarding biologic switching.

Conclusion

A sample of around 29,000 ulcerative colitis patients across 41 publications have been included in the real-world data analysis on the proportion of and outcomes of dose escalation, as well as treatment switching, of biologics.

Studies indicate that a significant number of ulcerative colitis patients dose escalate and switch treatments, with the most recurring switching pattern being from IFX → ADA reflecting current clinical practice.

Additional studies are needed to understand the time to which patients dose escalate or switch treatments, as well as the clinical outcomes resulting from dose escalation and treatment switching. These outcomes could ideally be used as a proxy indicator to measure the effectiveness of dose escalation and treatment switching in each biologic if strong evidence existed on the matter.

A greater amount of research would also be required in order to understand the gradient for escalation rates according to the different lines of treatment, as well as the occurrence of treatment switching, which would help in managing patients who lose response to biologic therapies.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Janssen Pharmaceutical NV, Beerse, Belgium funded the study.

Author contributions: The specific contribution of each author to this review is as follows. P.A. and D.W. designed the study. N.C.G., E.R. and P.A. conducted the literature search, data extraction and data analysis. N.C.G. and E.R. wrote the manuscript. A.B., D.W. and P.A. participated in the data analysis and manuscript revisions. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and final manuscript edits.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

N.C.G., E.R. and P.A. have disclosed that they are employees of an independent company, Amaris Consulting Ltd, that received funding for the contribution to the study design and data analyses. D.W. and A.B. have disclosed that they are employees of Janssen. CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express thanks to Dominik Naessens, Janssen Cilag NV, Beerse, Belgium, for critical review of the final manuscript.

References

- Bernstein CN, Ng SC, Lakatos PL, et al. A review of mortality and surgery in ulcerative colitis: milestones of the seriousness of the disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2001–2010.

- Pugliese D, Felice C, Papa A, et al. Anti TNF-α therapy for ulcerative colitis: current status and prospects for the future. Exp Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:223–233.

- Harbord M, Eliakim R, Bettenworth D, et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 2: current management. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2017;11:769–784.

- American Gastroenterological Association (AGA). Clinical care pathway of ulcerative colitis patients [Internet]. [cited 2018 Sep]. Available from: http://campaigns.gastro.org/algorithms/UlcerativeColitis/

- Allez M, Karmiris K, Louis E, et al. Report of the ECCO pathogenesis workshop on anti-TNF therapy failures in inflammatory bowel diseases: definitions, frequency and pharmacological aspects. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2010;4:355–366.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Vedolizumab for treating moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35:412–423.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab for treating moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis after the failure of conventional therapy (TA329). 2015.

- Royal College of Physicians. National clinical audit of biological therapies: annual report. UK inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) audit. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2016. ISBN 978-1-86016-624-2| eISBN 978-1-86016-625-9.

- Lindsay JO, Armuzzi A, Gisbert JP, et al. Indicators of suboptimal tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:1086–1091.

- Gisbert JM, McNicholl AG, Chaparro M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy of a second anti-TNF in patients with inflammatory bowel disease whose previous anti-TNF treatment has failed. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:613–623.

- Suzuki YM, Hanai H, Matsumoto T, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in Japanese patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:283–294.

- Makady A, de Boer A, Hillege H, et al. What is real-world data? A review of definitions based on literature and stakeholder interviews. Value Health. 2017;20:858–865.

- Probert CH, Schreiber S, Kühbacher T, et al. Infliximab in moderately severe glucocorticoid resistant ulcerative colitis: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2003;52:998–1002.

- (FDA) USFDA. Real world evidence [Internet]. Last updated 2017 Sep 18. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/science-research/science-and-research-special-topics/real-world-evidence.

- Einarson TR, Bereza BG, Ying Lee X, et al. Dose escalation of biologics in Crohn’s disease: critical review of observational studies. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33:1433–1449.

- Afif W, Leighton JA, Hanauer SB, et al. Open-label study of adalimumab in patients with ulcerative colitis including those with prior loss of response or intolerance to infliximab. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1302–1307.

- Alzafiri R, Holcroft CA, Malolepszy P, et al. Infliximab therapy for moderately severe Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: a retrospective comparison over 6 years. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2011;4:9.

- Amiot A, Grimaud JC, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab induction therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1593.e2–1601.e2.

- Angelison Sa L, Bajor A, Björk J, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with chronic active ulcerative colitis started on infliximab: a retrospective Swedish multicenter study. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2014;2(1S):A132–A605.

- Armuzzi A, Biancone L, Daperno M, et al. Adalimumab in active ulcerative colitis: a “real-life” observational study. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:738–743.

- Armuzzi A, Andrisani G, Papa A, et al. Long term sustainability of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis patients treated with infliximab. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:S90.

- Baert F, Vande Casteele N, Tops S, et al. Prior response to infliximab and early serum drug concentrations predict effects of adalimumab in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1324–1332.

- Baki E, Zwickel P, Zawierucha A, et al. Real-life outcome of anti-tumor necrosis factor α in the ambulatory treatment of ulcerative colitis. WJG. 2015;21:3282–3290.

- Black CM, Yu E, McCann E, et al. Dose escalation and healthcare resource use among ulcerative colitis patients treated with adalimumab in English hospitals: an analysis of real-world data. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0149692.

- Bressler B, Williamson MA, Camacho F, et al. Mo1902 real world use and effectiveness of golimumab for ulcerative colitis in Canada. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:S811.

- Cappello M, Mazza M, Costantino G, et al. Su1237 a retrospective multicenter survey on infliximab efficacy and safety in moderate-to-severe and steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:S-436.

- Cappello MM, Costantino G, Fries W, et al. Infliximab in steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis: lack of predictive factors for response in a large multicenter series. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:S78.

- Cesarini M, Katsanos K, Papamichael K, et al. Dose optimization is effective in ulcerative colitis patients losing response to infliximab: a collaborative multicentre retrospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:135–139.

- Christensen KR, Steenholdt C, Brynskov J. Clinical outcome of adalimumab therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis previously treated with infliximab: a Danish single-center cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1018–1024.

- Daperno M, Armuzzi A, Pugliese D, et al. Real-life prospective experience with adalimumab in ulcerative colitis in Italy: preliminary results of a pilot study. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:S297–S297.

- Dumitrescu G, Amiot A, Seksik P, et al. The outcome of infliximab dose doubling in 157 patients with ulcerative colitis after loss of response to infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:1192–1199.

- Echarri A, Lopez-Casado P, Fraga R, et al. Differences in biologic efficacy and dose-escalation among anti-TNF agents in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:S283.

- Fernández-Salazar L, Barrio J, Muñoz F, et al. Frequency, predictors, and consequences of maintenance infliximab therapy intensification in ulcerative colitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:527–533.

- Fernández-Salazar L, Barrio J, Muñoz C, et al. P463 Infliximab use in ulcerative colitis from 2003 to 2013: clinical practice, safety and efficacy. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2014;8:S259–S260.

- Hatoum HT, Patel H, Lin S-J, et al. Sa1120 indicators of inadequate response to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies in patients with ulcerative colitis from real-world practice settings. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:S-205.

- Hudis N, Rajca B, Polyak S, et al. W1132 the outcome of active ulcerative colitis treated with adalimumab. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:A-661.

- Hussey M, McGarrigle R, Kennedy U, et al. Long-term assessment of clinical response to adalimumab therapy in refractory ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:217–221.

- Iborra M, Pérez-Gisbert J, Bosca-Watts MM, et al. Effectiveness of adalimumab for the treatment of ulcerative colitis in clinical practice: comparison between anti-tumour necrosis factor-naïve and non-naïve patients. J Gastroenterol. 2016;52:1–12.

- Lindsay J, Gisbert J, Mody R, et al. PTH-070 A multinational study to determine indicators of suboptimal therapy among ulcerative colitis patients treated with tumour necrosis factor antagonists. Gut J. 2016;65:A254.

- Ladd AHM, Scott FI, Grace R, et al. Sa1086 dose escalation of vedolizumab from every 8 weeks to every 4 or 6 weeks enables patients with inflammatory bowel disease to recapture response. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:S235–S236.

- Naymagon S, Schneier A, Colombel J-F, et al. P-005 YI early dose-escalation of infliximab for colectomy avoidance in anti-TNF naive UC patients hospitalized with severe colitis; a tertiary-care center’s experience. Inflam Bowel Dis. 2013;19:S22–S23.

- Null KD, Xu Y, Pasquale MK, et al. Ulcerative colitis treatment patterns and cost of care. Value Health. 2017;20:752–761.

- Oussalah A, Evesque L, Laharie D, et al. W1294 predictors of primary non-response to infliximab and optimization in ulcerative colitis: a retrospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:S-693.

- Patel H, Lissoos T, Rubin DT. Indicators of suboptimal biologic therapy over time in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in the United States. PloS One. 2017;12:e0175099.

- Rostholder E, Ahmed A, Cheifetz AS, et al. Outcomes after escalation of infliximab therapy in ambulatory patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:562–567.

- Rubin D, Mody R, Wang CC, et al. Assessment of therapy changes and drug discontinuation among ulcerative colitis patients using health claims data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107.

- Salomonsson S, Söderberg J, Alenadaf K, et al. Dose escalation among ulcerative colitis patients treated with adalimumab in Sweden. Value Health. 2015;18:A633.

- Sandborn WJ, Sakuraba A, Wang A, et al. Comparison of real-world outcomes of adalimumab and infliximab for patients with ulcerative colitis in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:1233–1241.

- Takada Y, Yasukawa S, Amano R, et al. Factors related to short- and long-term treatment results and usefulness of infliximab for refractory ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:S259.2–S260.

- Taxonera C, Rodríguez C, Bertoletti F, et al. Clinical outcomes of golimumab as first, second or third anti-TNF agent in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1394–1402.

- Taxonera C, Olivares D, Mendoza JL, et al. Need for infliximab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9170.

- Taxonera C, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Calvo M, et al. Infliximab dose escalation as an effective strategy for managing secondary loss of response in ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:3075–3084.

- Taxonera C, Iglesias E, Muñoz F, et al. Adalimumab maintenance treatment in ulcerative colitis: outcomes by prior anti-TNF use and efficacy of dose escalation. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:481–490.

- Weil C, Chodick G, Yarden A, et al. Real-world treatment patterns with anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel disease in Israel. Value Health. 2016;19:A509–A510.

- Yamada S, Yoshino T, Matsuura M, et al. Long-term efficacy of infliximab for refractory ulcerative colitis: results from a single center experience. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:80.

- Yoshimura N, Sako M, Takazoe M. Su1017 comparative short and long-term efficacy of infliximab and adalimumab in patients with ulcerative colitis refractory to corticosteroids: a retrospective study. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:S444–S445.

- Amiot A, Serrero M, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. One-year effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective multicentre cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:310–321.

- Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 1: definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo-anal pouch disorders. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2017;11:649–670.