Abstract

Critical thinking is crucially important in both research and practice. This article demonstrates that a lack of critical thinking in two meta-analyses resulted in a conclusion that contradicts another meta-analysis and popular opinions. Kahwati et al. and Zhao et al. drew a conclusion that “Vitamin D supplementation alone or with calcium was not associated with reduced fracture incidence among community-dwelling adults without known vitamin D deficiency, osteoporosis, or prior fracture”, which apparently contradicted that of Tang et al. Kahwati et al. and Zhao et al. meta-analyzed vitamin D and/or calcium supplementation, which can decrease fracture risk factors, in a population with no known disorders of bone metabolism or vitamin D deficiency. They concluded that supplementation did not reduce fracture incidence. It is important to note that osteoporosis, which supplementation can prevent, and fractures are two distinct concepts. Zhao et al. presented their conclusion without including the conditions under which their conclusion was true. Subsequently, their conclusion was misleadingly interpreted by the public media as “Vitamin D and Calcium Don’t Prevent Bone Fractures” and “Vitamin D Does Not Prevent Falls, Calcium Does Not Prevent Fractures—A $2 Billion Waste of Money”. If study conclusions do not specify the applicable conditions, guidelines on medications, including supplements, are clinically unacceptable. Researchers must critically think about every step of their studies, including the way their conclusions are presented.

Critical thinking is crucially important in both research and practice; a lack of critical thinking may result in contradictory conclusions in research and diagnostic errors in practice. Recently, two meta-analyses attracted great attention due to their conclusions, which appear to contradict another meta-analysis with regard to whether the use of vitamin D and calcium supplementation are associated with reduced fracture incidence in adults 50 years and olderCitation1–3. The apparently contradictory conclusions, we believe, are due to lack of critical thinking, which created defects in the designs of the studies.

The meta-analyses of Kahwati et al. and Zhao et al.

The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among United States (US) adults is 28.9%Citation4. The prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mineral density (BMD) in adults 50 years and older in the US is 10.3 and 43.9%, respectivelyCitation5.

It is well established (“established theories”) that:

the rate of bone resorption exceeds the rate of bone deposition in elderly adults, eventually resulting in osteoporosis or low BMD;Citation6

calcium and vitamin D supplements are used to prevent osteoporosis;Citation3,Citation7,Citation8

vitamin D is indispensable for absorbing calcium;Citation6

osteoporosis or low BMD, vitamin D deficiency and prior fracture are risk factors for falls and fracturesCitation9–11.

With these established theories in mind, we believe that the study designs of Kahwati et al. and Zhao et al. resulted in a conclusion (“vitamin D supplementation alone or with calcium was not associated with reduced fracture incidence among community-dwelling adults”) that was seemingly original but, instead, reconfirmed these well-established theories in a population “without known vitamin D deficiency, osteoporosis, or prior fracture”Citation1, or unlikely needing vitamin D or calcium supplementationCitation2.

First, the population analyzed by Kahwati et al. did not have the fracture risk factors that are associated with calcium and vitamin D supplementation (“Studies of community-dwelling adults with no known disorders of bone metabolism or vitamin D deficiency were included. …” p. 1601)1; the population meta-analyzed by Zhao et al. likely did not need calcium and/or vitamin D to reduce fracture incidence (“Exclusion criteria were… (2) trials of participants with corticosteroid-induced secondary osteoporosis; (3) trials in which supplementation with calcium, vitamin D, or combined calcium and vitamin D was combined with other treatments [e.g. an antiosteoporotic drug]; (4) trials in which vitamin D analogues [e.g. calcitriol)] or hydroxylated vitamin D were used;” p. 2467)Citation2. Per the above established theories, “vitamin D supplementation alone or with calcium” (vitamin D ± calcium) in the above two populations neither decreased nor increased fracture risk. Therefore, vitamin D ± calcium supplementation in the above two populations should not be associated with reduced fracture incidence when compared with control groups because these patients do not need this supplementation to reduce fracture risk. Kahwati-Zhao et al. reconfirmed the established theories, providing no new information.

Second, the populations meta-analyzed by Kahwati et al. and Zhao et al. did not have vitamin D deficiency and osteoporosis or likely did not need calcium and/or vitamin D, indicating that their dietary intake of vitamin D and calcium was sufficient. Thus, it is unlikely that any benefit of the vitamin D and calcium supplementation would be detected (“if usual intake of calcium exceeds requirements, then it is unlikely that any benefit of the intervention will be detected”Citation12). It is misleading to report that no benefits of vitamin D and calcium supplementation were detected because this undetectability was determined by the study designs themselves.

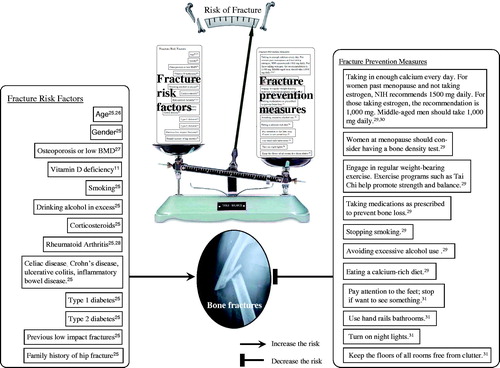

Third, osteoporosis (a bone density test T-score of −2.5 or lower) and fractures are two distinct concepts (“Risks for osteoporosis [reflected by low bone mineral density] and [risks] for fracture overlap but are not identical”Citation13). The outcomes or endpoints should be designed to be directly related to the effects of the treatmentCitation14. Specifically, the benefits of vitamin D ± calcium are directly related to BMD increases or osteoporosis prevention, not to the “fracture incidence”. In fact, the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) uses BMD, not osteoporosis, to evaluate fracture risk, indicating that BMD, not osteoporosis, is more directly associated with fracturesCitation15. Further, if vitamin D ± calcium was not associated with reduced fracture incidence in osteoporosis populations, it may simply indicate that supplementation, osteoporosis, and fractures are three distinct concepts and that a one-to-one relationship among the three concepts does not existCitation9. Vitamin D deficiency and osteoporosis are not the only risk factors of fractures, which result from the balance between risk factors and prevention measures ().

The meta-analysis of Tang et al.

In contrast to Kahwati-Zhao et al., Tang et al.:

recruited patients from the general population, including subjects with fracture risk factors (osteoporosis, vitamin D deficiency, and prior fractures). They found that “[t]he fracture risk reduction was significantly greater (24%) in trials in which the compliance rate was high (p < .0001)”Citation3, which is consistent with the established theories—vitamin D and calcium decrease fracture incidence by reducing modifiable risk factors (osteoporosis and vitamin D deficiency);

used BMD as one outcome, which was directly related to the treatment of vitamin D and calcium supplementation (“In trials that reported bone-mineral density as an outcome [23 trials, n = 41,419], the treatment was associated with a reduced rate of bone loss of 0.54% [0.35–0.73; p < .0001] at the hip and 1.19% [0.76–1.61%; p < .0001] in the spine”Citation3). Tang et al. further analyzed fracture incidence (“In trials that reported fracture as an outcome [17 trials, n = 52,625], treatment [vitamin D and calcium supplementation] was associated with a 12% risk reduction in fractures of all types [risk ratio 0.88, 95% CI 0.83–0.95; p = .0004]”Citation3).

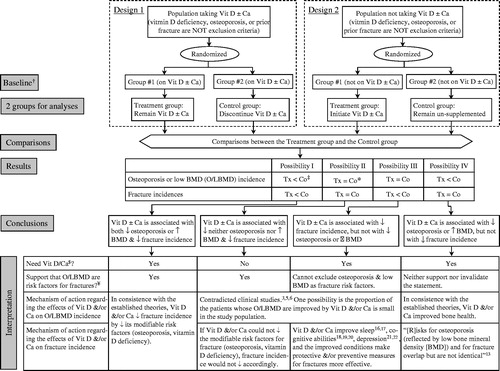

Considering the above, the conclusion of Tang et al. is more clinically meaningful (Design 2, Possibility I in ).

Figure 2. Critical thinking about the studies on the supplementation (vitamin D, calcium) and the incidences of osteoporosis and fractures. †Assuming no significantly differences in osteoporosis, low BMD, and fracture incidences between the two groups in baseline; ‡Incidence rate in the Treatment group is significantly lower than that in the Control group. This Figure does not algorithmize the situation, in which the incidence rates of osteoporosis, low BMD, or fractures in the Treatment group is significantly higher than that in the control group; *No significant difference regarding the incidence rates between the treatment group and the control group; $Need Vit D/Ca supplementation for the prevention of osteoporosis, low BMD, and/or fractures. ¥The assumption is accepted here that if X is a risk factor for a condition Y, X significant decrease would result in Y significant decrease, and vice versa, assuming that all other factors are the same. Abbreviations: Ca, Calcium; Co, Control group; Tx, Treatment group; vit: Vitamin.

Critical thinking on the above three meta-analyses

The conclusion of Kahwati et al. and Zhao et al. contradicted that of Tang et al. (“vitamin D ± calcium was not associated with reduced fracture incidence” vs. “vitamin D and calcium supplementation was associated with a significant risk reduction in fractures”) because the populations meta-analyzed by Kahwati et al. and Zhao et al. did not need the supplementation to reduce fracture risk. The study designs of Kahwati et al. and Zhao et al. actually determined the unassociation between the supplementation and reduced fracture incidence, while the study design of Tang et al. could not decide the association.

Critical thinking should be used in the study designs. First, to obtain conclusive results, supplementation must have an effect on the outcome (). Second, osteoporosis or low BMD is a risk factor for fracturesCitation9–11. The decrease of osteoporosis incidence is a sufficient cause for the decrease of fracture incidence, but not a necessary cause. That said, decrease of osteoporosis incidence results in a decrease of fracture incidence (Possibility I in ), but a decrease of fracture incidence does not necessarily indicate that osteoporosis incidence will decreases (Possibility III in ).

The work of Kahwati et al. and Zhao et al. would be of great clinical and social significance if:

“vitamin D deficiency, osteoporosis, or prior fracture” were not the exclusion criteria;

the studies compared osteoporosis, BMD, and fracture incidence between patients who continued supplementation with patients who discontinue supplementation (Design 1 in ).

Critical thinking is crucial to correctly interpret the possible results. For example, if osteoporosis incidence does not significantly decrease, but fracture incidence is significantly reduced in patients on the supplement (Possibility III in ), this result may indicate that the supplement has beneficial effects on sleepCitation16,Citation17, cognitive abilitiesCitation18–20, and depressionCitation21,Citation22. The improvement of these mental conditions makes protective or preventive measures for fractures more effective. This possibility alone can neither confirm nor deny that osteoporosis is a risk factor of fractures. On the other hand, if osteoporosis incidence significantly decreases but fracture incidence is not reduced in patients on the supplement (Possibility IV in ), by no means does it indicate that osteoporosis is not a risk factor because osteoporosis is not the only risk factor of fractures. As stated earlier, osteoporosis and fractures are two distinct concepts, and a one-to-one relationship between osteoporosis and fractures does not existCitation9. This possibility by itself cannot invalidate the statement that osteoporosis is a risk factor of fractures.

Critical consideration of conclusion presentation to avoid misinterpretation by the public

Public media misinterpreted the results of Kahwati-Zhao et al. as “Vitamin D and Calcium Don’t Prevent Bone FracturesCitation23.” One article was even titled “Vitamin D Does Not Prevent Falls, Calcium Does Not Prevent Fractures—A $2 Billion Waste of MoneyCitation24.” However, the public was never informed that:

the population in which vitamin D and/or calcium reportedly did not prevent bone fractures had no “known vitamin D deficiency, osteoporosis, or prior fracture;”

patients with vitamin D deficiency, osteoporosis, or prior fracture may need to take vitamin D ± calcium for bone health and fracture prevention;Citation3,Citation11

discontinuing vitamin D and calcium may result in vitamin D deficiency and/or osteoporosis.

Although it is the journalists who did not provide public sufficient background for an adequate understanding, researchers need to critically evaluate how they present their conclusions to avoid public misinterpretation of the conclusions. For example, in both the abstract and main text, Zhao et al. presented their conclusion without providing the condition under which their conclusions were reached: “the use of supplements that included calcium, vitamin D, or both compared with placebo or no treatment was not associated with a lower risk of fractures among community-dwelling older adults. These findings do not support the routine use of these supplements in community-dwelling older peopleCitation2.” Zhao et al. should have presented their conclusion as: “These findings do not support the routine use of these supplements in community-dwelling older people with no known disorders of bone metabolism or vitamin D deficiency.”

Conclusion

Policymakers should bear in mind that guidelines on the use of medications, including supplements, are clinically unacceptable if key details of studies (e.g. whether a study population has the disease or condition for which the medication is indicated) are not specified. Researchers must critically think about every step of their studies, including the way their conclusions are presented.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

No funding to disclose.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors and CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- Kahwati L, Weber R, Pan H, et al. Vitamin D, calcium, or combined supplementation for the primary prevention of fractures in community-dwelling adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1600–1612.

- Zhao J, Zeng X, Wang J, et al. Association between calcium or vitamin D supplementation and fracture incidence in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;318(24):2466–2482.

- Tang B, Eslick G, Nowson C, et al. Use of calcium or calcium in combination with vitamin D supplementation to prevent fractures and bone loss in people aged 50 years and older: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;370(9588):657–666.

- Liu X, Baylin A, Levy P. Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency among US adults: prevalence, predictors and clinical implications. Br J Nutr. 2018;119(8):928–936.

- Wright N, Looker A, Saag K, et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(11):2520–2526.

- Davies A, Blakeley A, Kidd C. Human physiology. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2001.

- Dawson-Hughes B, Harris S, Krall E, et al. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(10):670–676.

- Sunyecz J. The use of calcium and vitamin D in the management of osteoporosis. TCRM. 2008;4:827–836.

- Nguyen N, Eisman J, Center J, et al. Risk factors for fracture in nonosteoporotic men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(3):955–962.

- Johnell O, Gullberg B, Kanis J, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in European women: the MEDOS Study. Mediterranean Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;10(11):1802–1815.

- Sprague S, Petrisor B, Scott T, et al. What is the role of vitamin D supplementation in acute fracture patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of hypovitaminosis D and supplementation efficacy. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30(2):53–63.

- Weaver C, Gordon C, Janz K, et al. The National Osteoporosis Foundation's position statement on peak bone mass development and lifestyle factors: a systematic review and implementation recommendations. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(4):1281–1386.

- NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001;285:785–795.

- Hall A. Designing clinical trials for assessing the effectiveness of interventions for tinnitus. Trends Hear. 2017;21:2331216517736689.

- Kanis J, Johansson H, Harvey N, et al. A brief history of FRAX. Arch Osteoporos. 2018;13(1):118.

- Jamilian H, Amirani E, Milajerdi A, et al. The effects of vitamin D supplementation on mental health, and biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in patients with psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;94:109651.

- Zhao K, Luan X, Liu Y, et al. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in chronic insomnia patients and the association with poor treatment outcome at 2 months. Clin Chim Acta. 2017;475:147–151.

- Chen H, Liu Y, Huang G, et al. Association between vitamin D status and cognitive impairment in acute ischemic stroke patients: a prospective cohort study. CIA. 2018;13:2503–2509.

- Al-Amin M, Bradford D, Sullivan R, et al. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with reduced hippocampal volume and disrupted structural connectivity in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40(2):394–406.

- Sakuma M, Kitamura K, Endo N, et al. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D increases cognitive impairment in elderly people. J Bone Miner Metab. 2019;37(2):368–375.

- van den Berg K, Arts M, Collard R, et al. Oude Voshaar R. Vitamin D deficiency and course of frailty in a depressed older population. Aging Ment Health. 2018;15:1–7.

- Abdul-Razzak K, Almanasrah S, Obeidat B, et al. Vitamin D is a potential antidepressant in psychiatric outpatients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;56(12):585–596.

- Bakalar N. Vitamin D and calcium don’t prevent bone fractures. New York: New York Times; 2018. p. D4.

- Dinerstein C. Vitamin D does not prevent falls, calcium does not prevent fractures – a $2 billion waste of money; [cited 2019 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.acsh.org/news/2018/04/17/vitamin-d-does-not-prevent-falls-calcium-does-not-prevent-fractures-2-billion-waste-money-12843.

- The American Bone Health. Fracture risk factors; [cited 2019 Oct 12]. Available from: https://americanbonehealth.org/what-you-should-know/fracture-risk-factors/,

- Wu S-C, Rau C-S, Kuo SCH, et al. The influence of ageing on the incidence and site of trauma femoral fractures: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):413.

- Dhiman P, Andersen S, Vestergaard P, et al. Does bone mineral density improve the predictive accuracy of fracture risk assessment? A prospective cohort study in Northern Denmark. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e018898.

- Xue A-L, Wu S-Y, Jiang L, et al. Bone fracture risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(36):e6983.

- Stanford Health Care. Prevention of a hip fracture; 2019 [cited 2019 Oct 12]. Available from: https://stanfordhealthcare.org/medical-conditions/bones-joints-and-muscles/hip-fracture/treatments/prevention.html.

- NIH. Optimal calcium intake; 2019 [cited 2019 Oct 12]. Available from: https://consensus.nih.gov/1994/1994optimalcalcium097html.htm.

- The NIH Osteoporosis and Related Bone Diseases National Resource Center. Prevention of Falls and Fractures; 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.bones.nih.gov/health-info/bone/osteoporosis/fracture/preventing-falls-and-related-fractures#d