?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objective: To explore health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and assess preferences for medical treatment attributes to obtain information of the relative importance of the different attributes in a Danish population with ulcerative colitis (UC).

Methods: We used data from an online survey collected in March 2018 among people with self-reported UC. A total of 302 eligible respondents answered the HRQoL questionnaires (EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D-5L) and the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ)), and 212 also completed the discrete choice experiment (DCE). The probability of choosing an alternative from a number of choices in the DCE was estimated using a conditional logit model.

Results: The respondents had an average SIBDQ score of 4.5 and an HRQoL score of 0.77, applying the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire. HRQoL correlated with disease severity, and the respondents had lower HRQoL than did a gender- and age-matched subset of the Danish population. The most important medical treatment attribute was efficacy within eight weeks. Additionally, respondents stated a preference for avoiding taking steroids, for fast onset of effect and for oral formulations.

Conclusions: HRQoL correlates with disease severity, and patients with UC have lower HRQoL than the general population. The most important treatment attribute was efficacy, but patients also would like to avoid steroids, value fast onset of effect and prefer oral formulations.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterized by inflammation in the rectum and colon with symptoms including increased frequency of bowel movements, abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss and anaemiaCitation1,Citation2. The disease has an intermittent pattern with periods of flares and periods of remission. The annual incidence of UC varies geographically and increases over timeCitation3. In Denmark, it is estimated that the prevalence is approximately 30,000 and the annual incidence is approximately 850Citation4. The disease debut is most often seen in people of 15–40 yearsCitation1.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis exploring quality of life among patients with IBD (i.e. UC and Crohn’s disease (CD)) show that patients with IBD have worse health-related quality of life (HRQoL) than the general population, and patients with IBD have worse HRQoL in active disease states than during inactive diseaseCitation5,Citation6. However, the studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis use different tools to measure HRQoL; many of the included studies have small sample sizes; and the populations are a mix of UC and CD patients. While a few studies include Swedish, Norwegian and Finnish patients, none have explored HRQoL in a Danish population of UC.

Understanding patient preferences and how they are associated with factors such as treatment outcome and adherence and acceptance of treatment alternatives is of interest to the medical community, including clinicians, policy makers and researchersCitation7–10. Accordingly, the American Gastroenterological Association states that assessing patient preferences is a first step after diagnosis in the clinical care pathway for UCCitation11. However, while the interest in studying patient preference is increasing, there is currently limited evidence of what UC patients actually prefer. We have identified a few studies focusing on patient preferences among UC patients, but heterogeneous approaches regarding methodology, population and treatment attributes complicate comparison of results across studiesCitation12–15.

Studies have shown differences between health care professionals’ (HCPs) and patients’ perceptions of disease burden and preferences for UC treatment attributesCitation16,Citation17. Indeed, HCPs may underestimate the effect of specific UC symptoms on patients’ lives or fail to recognize issues that are important to patientsCitation18. Therefore, there is a need to involve the patient’s perspective in all matters of treatment choices, whenever the patient interacts with the health care system, when choosing between treatment possibilities, and during the regulatory approval process for new drugs.

The aim of this study was to explore HRQoL in a Danish population with UC and to elicit patients’ preferences and expectations for advanced treatments, such as biologic treatments, applying the discrete choice experiment (DCE) methodologyCitation19.

Methods

This study is part of a larger study designed as a descriptive and cross-sectional survey among people with UC. The questionnaire was developed in collaboration with the Danish patient organization for UC and CD (Colitis-Crohn Foreningen). Data were collected online in March 2018 among Danish people with UC. In this paper, we present analyses from the HRQoL and DCE parts of the survey.

The inclusion criteria were ability to read and understand Danish, self-reported UC, disease without a colectomy, and age ≥18. The respondents were recruited online by Colitis-Crohn Foreningen in open forums and via the organization’s webpage, and the survey was answered online.

This study follows the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and is conducted under the approval of the Danish Data Supervision (Datatilsynet). In Denmark, no ethical approval is needed to conduct survey studies. It was confirmed by the Regional Ethical Committee in the Capital Region that this study does not need an ethical approval. Written informed consent was obtained from each individual participating in the study.

Survey instrument

The questionnaire included items about patients’ demographics, preferences, quality of life, impact of disease and symptoms on daily life, disease history, and socio-demographics. The questionnaire development was an iterative process; we searched literature about previous preference studies and ranges of attributes for advanced treatments of UC. Our study was aimed at being as patient-centered as possible. The questionnaire development was therefore performed in collaboration with Colitis-Crohn Foreningen, with input from patient organization representatives as well as patients living with UC. It was qualitatively tested with three patients and quantitatively tested with 36 patients. The questionnaire was developed and answers were collected through the survey program SurveyXact (Ramboll , Aarhus, Denmark).

Quality of life questionnaires

The questionnaire included two patient-reported outcome measures to elicit HRQoL – one generic (EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D-5L)) and one disease-specific (the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ)). We decided to include both measurements to be able to compare to both UC-specific results and across indication results of other HRQoL-studies.

EQ-5D-3L is one of the most used patient-reported outcomesCitation20. The instrument elicits problems on five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. In an updated version of the tool, the EQ-5D-5L, the categories for each dimension are more detailed, with the following answer categories: no, little, moderate, large or extreme problems.

There is currently no Danish calculation norm for translation of health states in the EQ-5D-5L. Instead we used official calculations from England to calculate the different combinations of health states to arrive at quality of life valuesCitation21. In this calculation, the worst possible score is –0.285, where respondents have extreme problems on all five dimensions, while the best possible score is 1, where respondents report no problems on all five dimensions. A score of 0 represents a health state that corresponds to death, while health values below 0 represent health states valued as worse than death.

In a study from 2009, among a representative selection of the Danish population, average HRQoL stratified by gender and age was elicited by the instrument EQ-5D-3LCitation22. We have used these values to calculate a weighted average with the same age and gender distribution as in our survey sample.

In this survey, we asked the patients to fill out the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire two times to assess their HRQoL when their disease was in remission and during a flare.

SIBDQ is a shortened version of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ)Citation23. The SIBDQ measurement tool consists of 10 questions, each with seven answer categories (all of the time, most of the time, a good bit of the time, some of the time, a little bit of the time, hardly any of the time, none of the time).

The score ranges from 1 to 7, where higher numbers equal higher HRQoL. There are four sub-scores of the SIBDQ: bowel symptoms, systematic symptoms, social function and emotional function. The sub-scores also range from 1 to 7.

Discrete choice experiment

The experiments were conducted according to research practices as described by Johnson et al.Citation19. Each treatment alternative was combined by four attributes, with different levels within each attribute. To reduce the number of possible alternatives to a manageable number, a standardized process in the Ngene software (ChoiceMetrics, Sydney, NSW, Australia) was applied, which led to a fractional design that was both orthogonal and balanced.

Attributes were determined based on a review of the literature and on interviews with patient organization representatives and patients. The four attributes we included were mode of administration, efficacy (significant improvement of symptoms), time to certainty about effect and steroid use. These attributes were chosen based on significance for the patient in the clinical decision scenario as well as their daily life living with advanced treatments for UC. The levels of the first three attributes were chosen based on clinical available data on advanced/biologic treatment options, primarily Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC). The levels for steroid use were based on patient interviews.

Before respondents were presented with the DCE items in the questionnaire, we described the different attributes in more detail (e.g. what was meant by “significant improvement” in symptoms). We assumed preferences would be linear for efficacy and time to certainty about effect. For the two other attributes (mode of administration and steroid use), we asked about the respondents’ preferences for each level when all other treatment attributes were equal before presenting the DCE choices. See for all possible attributes and levels and for an example of a DCE item as seen by respondents.

Table 1. Attributes and levels in the discrete choice experiment.

Table 2. Example of discrete choice experiment item.

To ensure that respondents understood the concept of the DCE, we included a test question where respondents were asked to choose between two alternatives, one of which dominated the other (i.e. there was no trade-off). As is standard practice, those who failed the test question were excluded from the studyCitation24. In addition, we asked respondents if they were certain about their answers in the DCE questions. If they were uncertain, we asked why. If respondents stated that they did not understand the questions, that they were bored or that they wished the survey to be done with fast, their answers were excluded from analysis.

Statistical analysis

The conditional logit model was used to estimate the probability of choosing alternative j from nj choices in the choice scenario i. The model can be described as follows:

where there are ni=2 choices in each choice set, Ci. The preference weights for each attribute level are expressed by the parameters β. The parameters show the relative importance of each attribute to each other. As the estimates are calculated as a ratio of two stochastic variables and it is impossible to derive confidence intervals (CIs) directly from the conditional logit model, we carried out bootstrapping with 10,000 iterationsCitation22.

All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA) and Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA, USA).

Results

Population

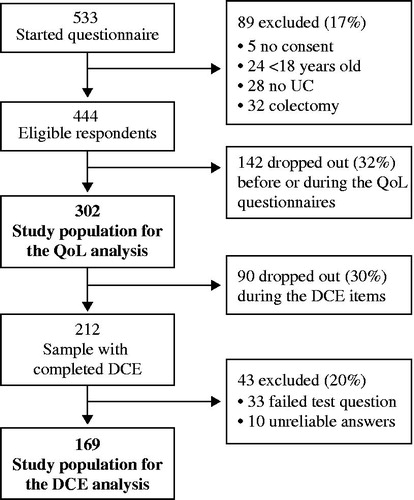

In total, 533 respondents started the questionnaire. Of those, 302 were included in the quality of life analysis, and of these, 169 were included in the DCE analysis (). Of the 231 respondents who were excluded from the quality of life analysis, 89 did not meet the inclusion criteria and 142 dropped out before or during the administration of the quality of life questionnaires. Moreover, 90 dropped out during the DCE items, and 43 were excluded from the analysis because of unreliable answers. There were no statistical differences in the characteristics of the excluded respondents compared with the included respondents (see Supplementary material).

Among the 302 respondents in the quality of life analysis sample, 90 (30%) had self-reported mild disease, 106 (35%) had moderate disease, 53 (18%) had severe disease and 53 (18%) were uncertain about their disease severity (). The average age was 39.7 years (standard deviation (SD): 12.4), and 84% were women. On average, the respondents had experienced symptoms they later associated with UC for 12.0 years and had the diagnosis for 9.6 years. The majority (71%) lived with a partner with or without children, 21% lived alone with or without children, and 8% lived either at home with parents or with other adults (). Seventy percent of patients were employed (55% full time, 16% part time), 9% were studying and 8% were retired.

Table 3. Population characteristics stratified by self-reported disease severity, among 302 patients with ulcerative colitis.

Table 4. Household and employment status stratified by self-reported disease severity, among 212 patients with ulcerative colitis.

Quality of life

The generic HRQoL measurement tool EQ-5D-5L ranges from –0.285 to 1, where 1 is the equivalent of perfect health and 0 is equivalent of death. Health states with scores below 0 are equivalent to “worse than death” health states. In this cross-sectional study, the mean score was 0.77 (SD: 0.20) (). Based on Sørensen et al.Citation22, we calculated a mean EQ-5D-5L score for a matched subset of the Danish population with the same age and gender distribution as our population. The estimate of this population is 0.89 (SD: 0.03). Thus, the respondents in this study have significantly worse HRQoL than an age- and gender-adjusted sample of the Danish population (p < .001).

Table 5. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) based on EQ-5D-5L, among 302 patients with ulcerative colitis.

Additionally, we estimated HRQoL during flares and remission. In the overall sample, the HRQoL in remission was 0.83 (SD: 0.17), while during a flare of the disease their HRQoL was 0.56 (SD: 0.31) (p < .001).

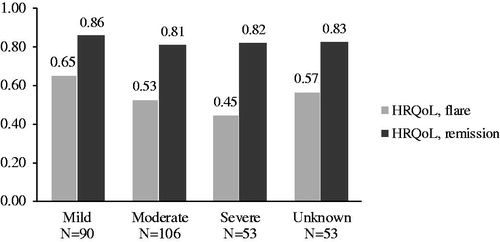

shows the HRQoL estimates for flares and remission of disease stratified by disease severity. While the estimates for remission of disease are almost identical across disease severity (mild: 0.86, moderate: 0.81, severe: 0.82, unknown: 0.83), there is a clear tendency of worsening HRQoL during flares as disease severity worsens. Respondents with mild disease had an HRQoL during a flare of 0.65; respondents with moderate disease had an HRQoL during flares of 0.53; and respondents with severe disease had an HRQoL during flares of 0.45. Respondents with unknown disease severity had an HRQoL during flares of 0.57, indicating a disease severity between mild and moderate.

Figure 2. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) stratified by disease severity, flare and remission, among 302 patients with ulcerative colitis.

The SIBDQ score range from 1 to 7, where 1 is the worst score and 7 is the best score. The respondents had a mean score of 4.5, with correlation to disease severity (). Respondents with self-reported mild disease (n = 90) had a mean score of 5.1, respondents with moderate disease (n = 106) had a mean score of 4.3 and respondents with severe disease (n = 53) had a mean score of 3.9. Respondents with unknown disease severity had a mean score of 4.7, indicating a severity between mild and moderate.

Table 6. SIBDQ scores and sub-scores stratified by disease severity, among 302 patients with ulcerative colitis.

Of the four sub-scores – bowel symptoms, systemic symptoms, social function and emotional function – the worst are bowel symptoms (4.4) and emotional function (4.4), with systemic symptoms and social function both having a mean score of 5.3. The trend of worse scores with worse disease severity is also seen in all of the sub-scores, where respondents with severe disease had a mean score for emotional function of 3.7 compared to respondents with mild disease, who had a mean score of 5.0. For bowel symptoms, respondents with severe disease had a mean score of 4.0, whereas respondents with mild disease had a mean score of 5.1.

Preferences

Simple preferences

Of the 212 respondents included in the DCE analysis, 85% had received oral tablets, 12% had tried subcutaneous (SC) injections and 26% had tried intravenous (IV) infusion. Twelve percent had not tried any of the three included modes of administration.

When asked which of the three described methods of administering medication for UC they favored, 66% stated that they preferred oral tablets twice daily, 19% preferred SC injections every four weeks and 15% preferred infusions every eight weeks.

One-third of the respondents never took steroids (31%), 45% took steroids only during flares, 15% took them during flares and if needed between flares, and 3% reported that they always took steroids. When asked about their preference for steroid use, 70% stated that they preferred never to take steroids, while 30% stated that they preferred to take steroids when in treatment for flares.

DCE results

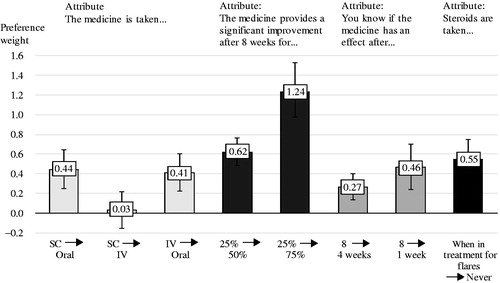

shows the coefficients of the statistical model corresponding to the respondents’ relative preference for the included UC treatment attributes, where each estimate is presented with all other attributes equal. Higher numbers indicate higher preference, and 0 indicates no preference. Due to the assumption of linearity of preference for changes in efficacy, the preference expressed in the figure depends on the magnitude of the assumed change. Accordingly, the attribute respondents have the highest preference for is that there is a chance of 75% instead of 25% that the medicine provides a significant improvement after eight weeks. This increase from 25% to 75% has a preference weight of 1.24 (95% CI: 0.97–1.53). The assumption of linearity means that respondents value half of the improvement (50% of patients instead of 25% of patients who experience significant improvements after eight weeks) as half as preferable, with a preference weight of 0.62 (95% CI: 0.48–0.76). When testing the assumption of linearity, we found that there is a higher preference for the first category (from 25% to 50%) than the second (from 50% to 75%). We decided to keep the assumption of linearity despite this, because we find it relevant to be able to use the estimates for actual products where the difference in efficacy will not exactly mirror the levels in our study.

Figure 3. Preference weights of attributes, among 212 patients with ulcerative colitis. Note: The figure shows coefficients from the statistical model. All levels are significant, except SC vs. IV. The raw coefficients can be found in the Supplementary material. Abbreviations. SC, Subcutaneous injections every four weeks; Oral, Oral tablets twice daily; IV, Intravenous infusions every eight weeks.

“Never taking steroids” compared to “taking steroids when in treatment for flares” has a preference weight among the respondents of 0.55 (95% CI: 0.36–0.75). To know with certainty that the treatment has an effect after one week compared with eight weeks has a preference weight of 0.46 (95% CI: 0.24–0.70), whereas to know with certainty that the treatment has an effect after four weeks compared with eight weeks has a preference weight of 0.27 (95% CI: 0.14–0.40). We also tested the assumption of linearity for this parameter, and the assumption of linearity could not be rejected with a significance level of 95%.

As was seen in the simple preference questions, oral tablets twice daily are preferred by the respondents to SC injections every four weeks and to IV infusions every eight weeks. There was no significant difference in preference for respondents between the SC and the IV mode of administration. To get treatment as oral tablets twice daily compared to SC injections every four weeks had a preference weight of 0.44 (95% CI: 0.25–0.64), and compared to IV injections every eight weeks had a preference weight of 0.41 (95% CI: 0.22–0.60).

We tested the effect of not excluding respondents with unreliable answers, and the analysis showed no significant difference in the preferences (see Supplementary material). We therefore kept the unreliable answers out of the analysis.

Discussion

This study shows the HRQoL among a Danish UC population. We found that people with UC have lower HRQoL than a gender- and age-adjusted general population and that the HRQoL is dependent on disease severity as well as on whether the disease is active (during a flare) or in remission. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show the correlation of HRQoL, disease severity and disease activity in a UC population. While respondents have almost equal HRQoL during remission independent on disease severity, we show a significant decrease from mild to severe disease during flares.

The HRQoL as measured with SIBDQ compares to international studiesCitation25–27. Furthermore, a number of studies show that QoL is related to disease activity in patients with UCCitation28–31. The HRQoL in patients with UC is significantly influenced by their disease as compared to the general populationCitation30, and a higher disease activity correlates with a lower HRQoL in patients with UCCitation32.

The impact of the disease on HRQoL is comparable to other diseases. In arthritis, a number of studies have demonstrated significantly lower quality of life compared to the general population both in patients with rheumatoid arthritisCitation33–37 and in those with psoriatic arthritisCitation38–41. This underlines the need for new treatment options.

In the current study, we observed that the respondents had a significant preference for the included attributes. As might be expected, the efficacy measure was of highest preference to the respondents, which is also supported by findings in previous studiesCitation13,Citation42. However, an interesting finding was the high value respondents put on avoiding taking steroids during flares. Steroids (such as prednisolone) are recommended as treatment during flares by the Danish national guidelines as well as international guidelinesCitation43–45. This type of treatment is perceived as very effective in inducing remission but is, on the other hand, associated with different adverse eventsCitation46, which could be one of the reasons respondents prefer to avoid them, if possible.

Respondents’ preference for faster certainty of effect is also significant. Previous studies of IBDs have likewise found that fast relief was one of the most important attributes to the patientsCitation12,Citation42.

We saw that there was no difference in respondents’ preferences between taking medication as IV infusions every eight weeks and SC injections every four weeks. However, respondents view oral tablets twice daily as preferable to both the SC injections and IV infusions. The fact that oral formulations are preferred to SC injections or IV infusions is supported by previous studies, e.g. in Gregor et al.Citation42, where patients with UC or CD preferred oral tablets to injections. In that study, however, short infusions (30–60 min) and long infusions (2–3 h) were preferred a little more and a little less, respectively, to the oral mode of administration. Alten et al.Citation47 found that among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, oral tablets were significantly preferred to both IV infusions and SC injections. In the two studies, however, the mode of administration and frequency of administration were not combined, which might explain the differences in preference across the studies. In a study by Torbica et al.Citation48, patients with psoriasis preferred IV infusions monthly and SC injections quarterly over oral tablets daily. This underlines the fact that both mode of administration and frequency influence patient preference but indicates that there might be difference across disease areas for similar types of treatment administration.

The order of attributes in the DCE questions may affect respondent behavior, which means that there is a possibility that some attributes are overestimated and others are underestimated in our study. However, taking the CIs into account, we believe the results are valid and show the relative preference of the respondents.

Although our respondents were recruited through the patient organization, our sample population differs somewhat from the general UC population in Denmark; e.g. the sample has a large proportion of females to males (84% females vs. 16% males), and a larger proportion of the study population comprises individuals who have experience with advanced/biologic treatment (either IV or SC) compared to the estimated share in Denmark (26% vs. 6% on advanced/biologic vs. conventional treatment)Citation4. This means that the results are not representative of the entire UC population in Denmark. The differences between populations might be due to the online recruitment method used. A previous Danish study similarly reported 70% female respondents, indicating a higher interest among women for participation in online surveysCitation49. Due to the small sample size, we were not able to conduct subgroup analyses on the DCE estimates. It would, however, be interesting to further investigate how demographic, socioeconomic or disease-specific factors influence patient preferences.

In addition to our present study, we have identified three other DCE studies within the UC disease area that focused on different aspects of medical treatment of UCCitation13,Citation14,Citation42. Gregor et al. studied the preferences among 586 Canadian patients with CD or UC for 12 different attributes of medical treatment of CD and UCCitation42. They found that patients preferred reducing pain during administration as well as mucosal healing and symptom relief.

Hodgkins et al. studied UC patients with mild to moderate disease severity (n = 400, 100 from each country: US, UK, Germany and Canada) and their preference for 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA)Citation13. They found that the most valued attributes were the effectiveness of treatments (symptom control and risk of disease flare-ups) but that geographical differences existed in the strength of preference for the convenience of taking the medication and patients’ willingness to pay for treatment alternatives.

Bewtra et al. completed a DCE study to examine the willingness to accept risks of chronic immunosuppression to avoid surgery (colectomy) among 293 UC patients from the USCitation14. In the study, they found a strong preference for avoiding surgery and a willingness to accept relatively high risks of fatal complications from medical therapy to avoid a permanent ostomy and to achieve durable clinical remission.

We did not include the option of surgical treatment in our study, because the aim of the study was to understand patient preference for advanced medical treatments before surgery.

Strengths and limitations

We recognize a number of strengths and limitations with our study design. First, it is a strength that the questionnaire was developed and validated by patients, ensuring the patient perspective all through the study. Second, we included both a generic and a disease-specific quality of life measure. In addition, it is a strength that we elicit patients’ preferences through continuous choice situations, which is a situation well known to respondents because it is similar to daily consumer situations. Compared with simple preference questions, the DCE method also has the advantage of being based on making choices between different alternatives, reducing strategic behavior and making it possible to estimate preferences for attributes rather than the good as a whole. Additionally, DCE pair-wise ordinal choices have been shown to be cognitively easier than other preference tasks, such as multi-criteria decision analysis, and collecting larger sample sizes is easier with electronic DCE than with methods that require more interaction or consensus among respondentsCitation50. Additionally, DCE questions are not presented as yes or no questions, but as a choice between two goods. This design prevents the problem of respondents overstating the number of actual yes answers – the “yea-saying” problemCitation51.

A limitation to the DCE methodology is that some respondents might use simplifying strategies such as choosing based on only one attribute. It has been documented that this type of strategy is more prevalent among younger people, people with lower education and those with a lower health literacyCitation50. Another limitation of the DCE methodology is that the cognitive burden of repeated choice situations can lead to respondent fatigue, which may lead to drop-out or irrational choices. We saw a relatively high proportion of respondents (n = 232) who dropped out, and 43 respondents were excluded (20%) from the analysis because of unreliable answers. While the drop-out rate and exclusion rate might have affected the results of the study, we tested the DCE results with and without the respondents excluded due to unreliable answers. This analysis did not show any statistically significant difference in the answers (see Supplementary material).

A limitation to the attributes included in the DCE is that we chose not to include adverse events as a differentiating factor in the treatment attribute. This is a known and significant attribute in all medical treatments. There were a couple of reasons for the exclusion. The DCE setup can very quickly become too complex for respondents if too many attributes or levels are included. We chose to include four attributes with two or three levels in each. If we were to include adverse events, it would have been difficult to describe the possible attributes as realistic without being very complex. Adverse events are often reported as risks, which are known to be difficult to communicate clearly in writing to patients so that they comprehend the risks adequatelyCitation52. In addition to this, the many types of adverse events would have to be sorted and selected in the design of the study in order not to be too complex for the patients to understand in context of the other attributes. Thus, we decided to exclude any description of adverse events (assuming equal adverse events), to reinforce high-quality answers on the other attributes, although we acknowledge this as a limitation of the study. We will therefore suggest further investigation into how patient preferences for advanced treatment alternatives are influenced by different adverse event profiles.

Another limitation is the risk of recall bias when estimating the difference in HRQoL during and between flares. Here we rely on the respondents’ memory of the last time they had a flare/the last time they did not have a flare.

A final limitation is related to the recruiting method. We recruited online, which means that the diagnosis of UC is self-reported. We asked respondents if a physician had diagnosed them with UC, and respondents who answered yes were included in the analysis. Likewise, the disease severity (mild, moderate, severe) is self-reported.

While disease severity was self-reported, we included questions in the survey about symptoms, where we could see that people who reported more severe diseases also reported more severe symptoms (data not shown).

Conclusions

In this study, we have shown that HRQoL correlates with disease severity and whether the disease is active (during a flare) or in remission. Danish patients with UC have lower HRQoL than a gender- and age-matched subset of the general population. Additionally, we show preferences for advanced treatment alternatives among Danish patients with UC. All four included attributes were significant in the respondents’ choices. The most preferred attribute was efficacy of treatment. Respondents also stated a preference for avoiding taking steroids, for fast onset of effect and for oral formulations.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by Pfizer Denmark.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

LMH is an employee at Pfizer Denmark. SES and HHJ are employees at Incentive. Incentive is a paid vendor of Pfizer Denmark. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Arne Yndestad and Trine Pilgaard, both employees of Pfizer, for their review of the final article.

References

- Ordás I, Eckmann L, Talamini M, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2012;380(9853):1606–1619.

- Danese S, Fiocchi C. Ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(18):1713–1725.

- Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(1):46–54.e42. quiz e30.

- RADS. Baggrundsnotat for dyre lægemidler til behandling af kroniske inflammatoriske tarmsygdomme [Background note for expensive drugs for the treatment of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases]. Danish; 2016.

- Knowles SR, Graff LA, Wilding H, et al. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analyses—part I. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(4):742–751.

- Knowles SR, Keefer L, Wilding H, et al. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analyses—part II. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(5):966–976.

- Bastemeijer CM, Voogt L, van Ewijk JP, et al. What do patient values and preferences mean? A taxonomy based on a systematic review of qualitative papers. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(5):871–881.

- Zhang Y, Coello PA, Brożek J, et al. Using patient values and preferences to inform the importance of health outcomes in practice guideline development following the GRADE approach. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):52.

- Postmus D, Mavris M, Hillege HL, et al. Incorporating patient preferences into drug development and regulatory decision making: results from a quantitative pilot study with cancer patients, carers, and regulators. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99(5):548–554.

- Ho M, Saha A, McCleary KK, et al. A framework for incorporating patient preferences regarding benefits and risks into regulatory assessment of medical technologies. Value Health. 2016;19(6):746–750.

- Dassopoulos T, Cohen RD, Scherl EJ, et al. Ulcerative colitis care pathway. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(1):238–245.

- Gray JR, Leung E, Scales J. Treatment of ulcerative colitis from the patient’s perspective: a survey of preferences and satisfaction with therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(10):1114–1120.

- Hodgkins P, Swinburn P, Solomon D, et al. Patient preferences for first-line oral treatment for mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: a discrete-choice experiment. Patient. 2012;5(1):33–44.

- Bewtra M, Kilambi V, Fairchild AO, et al. Patient preferences for surgical versus medical therapy for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(1):103–114.

- Casellas F, Herrera-de Guise C, Robles V, et al. Patient preferences for inflammatory bowel disease treatment objectives. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49(2):152–156.

- Schreiber S, Panés J, Louis E, et al. Perception gaps between patients with ulcerative colitis and healthcare professionals: an online survey. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12(1):108.

- Rubin DT, Siegel CA, Kane SV, et al. Impact of ulcerative colitis from patients’ and physicians’ perspectives: results from the UC: NORMAL survey. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(4):581–588.

- Lönnfors S, Vermeire S, Greco M, et al. IBD and health-related quality of life – discovering the true impact. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(10):1281–1286.

- Johnson R, Lancsar E, Marshall D, et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16:3–13.

- Devlin NJ, Brooks R. EQ-5D and the EuroQol Group: past, present and future. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(2):127–137.

- Devlin NJ, Shah KK, Feng Y, et al. Valuing health-related quality of life: an EQ-5D-5L value set for England. Health Econ. 2018;27(1):7–22.

- Sørensen J, Davidsen M, Gudex C, et al. Danish EQ-5D population norms. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37(5):467–474.

- Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Barton JR, et al. The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire is reliable and responsive to clinically important change in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(10):2921–2928.

- Ryan M, Farrar S. Using conjoint analysis to elicit preferences for health care. BMJ. 2000;320(7248):1530–1533.

- Kappelman MD, Long MD, Martin C, et al. Evaluation of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(8):1315–1323.e2.

- Burisch J, Weimers P, Pedersen N, et al. Health-related quality of life improves during one year of medical and surgical treatment in a European population-based inception cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease — an ECCO-EpiCom study. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(9):1030–1042.

- Van Assche G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sturm A, et al. Burden of disease and patient-reported outcomes in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in the last 12 months – Multicenter European cohort study. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48(6):592–600.

- Kodate N. Events, public discourses and responsive government: quality assurance in health care in England, Sweden and Japan. J Pub Pol. 2010;30(3):263–289.

- Kawalec P, Stawowczyk E, Mossakowska M, et al. Disease activity, quality of life, and indirect costs of ulcerative colitis in Poland. Prz Gastroenterol. 2017;12:60–65.

- Nedelciuc O, Pintilie I, Dranga M, et al. Quality of life in patients with ulcerative colitis. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2012;116(3):756–760.

- Zahn A, Hinz U, Karner M, et al. Health-related quality of life correlates with clinical and endoscopic activity indexes but not with demographic features in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(11):1058–1067.

- Panés J, Domènech E, Peris MA, et al. Association between disease activity and quality of life in ulcerative colitis: results from the CRONICA-UC study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32(11):1818–1824.

- Wan SW, He H-G, Mak A, et al. Health-related quality of life and its predictors among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;30:176–183.

- Anyfanti P, Triantafyllou A, Panagopoulos P, et al. Predictors of impaired quality of life in patients with rheumatic diseases. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(7):1705–1711.

- Hoshi D, Tanaka E, Igarashi A, et al. Profiles of EQ-5D utility scores in the daily practice of Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis; analysis of the IORRA database. Mod Rheumatol. 2016;26(1):40–45.

- Hernández Alava M, Wailoo A, Wolfe F, et al. The relationship between EQ-5D, HAQ and pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2013;52(5):944–950.

- Cho S-K, Kim D, Jun J-B, et al. Factors influencing quality of life (QOL) for Korean patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(1):93–102.

- Kawalec P, Malinowski KP, Pilc A. Disease activity, quality of life and indirect costs of psoriatic arthritis in Poland. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36(9):1223–1230.

- Michelsen B, Uhlig T, Sexton J, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis: data from the prospective multicentre NOR-DMARD study compared with Norwegian general population controls. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(9):1290–1294.

- Carneiro C, Chaves M, Verardino G, et al. Evaluation of fatigue and its correlation with quality of life index, anxiety symptoms, depression and activity of disease in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:155–163.

- Gratacós J, Daudén E, Gómez-Reino J, et al. Health-related quality of life in psoriatic arthritis patients in Spain. Reumatol Clín (English Edition). 2014;10(1):25–31.

- Gregor JC, Williamson M, Dajnowiec D, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease patients prioritize mucosal healing, symptom control, and pain when choosing therapies: results of a prospective cross-sectional willingness-to-pay study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:505–513.

- Kornbluth A, Sachar DB, Practice Parameters Committee of The American College of Gastroenterology. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(3):501–523, quiz 524.

- Harbord M, Eliakim R, Bettenworth D, et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(7):769–784.

- Dansk Selskab for Gastroenterologi og Hepatologi (DSGH). Akut svær coltitis ulcerosa [Acute severe ulcerative colitis]. Danish; 2016.

- Probert C. Steroids and 5-aminosalicylic acids in moderate ulcerative colitis: addressing the dilemma. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6(1):33–38.

- Alten R, Krüger K, Rellecke J, et al. Examining patient preferences in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis using a discrete-choice approach. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2217–2228.

- Torbica A, Fattore G, Ayala F. Eliciting preferences to inform patient-centred policies: the case of psoriasis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(2):209–223.

- Rasmussen R, Hjarsbech P. Oplevelser af behandlingsforløb og sygdomskonsekvenser blandt nuværende medlemmer af Colitis-Crohn Foreningen [Experiences of treatment and disease consequences among current members of the Colitis-Crohn Foreningen]. Danish: KORA; 2016.

- Tervonen T, Gelhorn H, Sri Bhashyam S, et al. MCDA swing weighting and discrete choice experiments for elicitation of patient benefit-risk preferences: a critical assessment. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(12):1483–1491.

- Bateman IJ, Carson RT, Day B, et al. Economic valuation with stated preference techniques: a manual. Cheltenham (UK): Edward Elgar; 2002.

- Naik G, Ahmed H, Edwards A. Communicating risk to patients and the public. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(597):213–216.