Abstract

Objective: To assess the real-world use of home health services (HHS) among patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) with and without treatment-resistant depression (TRD).

Methods: Adults (18–64 years) from a commercial claims database (07/2009 to 03/2015) were categorized into three cohorts: “TRD”(N = 6411), “non-TRD MDD”(N = 33,068), “non-MDD”(N = 149,884) stratified based on use of HHS (HHS vs. no-HHS). Healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and costs were evaluated up to two years following the first antidepressant pharmacy claim using descriptive statistics. HRU (e.g. inpatient, outpatient, emergency department visits) and costs were measured per-patient-per-year (PPPY) in 2015 USD.

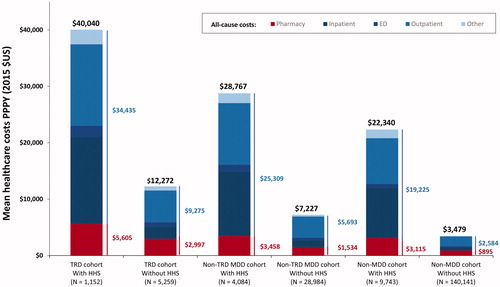

Results: During the follow-up period, 18.0% of TRD, 12.4% of non-TRD MDD, and 6.5% of non-MDD patients received HHS. Mean all-cause healthcare costs PPPY were numerically higher among patients with HHS use. Among the TRD cohort, patients using HHS had healthcare costs of $40,040 PPPY while patients with TRD and no-HHS had healthcare costs of $12,272 PPPY. Within the non-TRD MDD cohort, HHS users incurred healthcare costs of $28,767 PPPY and non-HHS users incurred costs of $7227 PPPY. Patients without MDD who used HHS had annual healthcare costs of $22,340 while non-MDD patients who did not use HHS had healthcare costs of $3479 PPPY. However, among HHS users, HHS costs represented a relatively small proportion of total healthcare costs.

Conclusions: The high proportion of TRD patients using HHS suggests it is a utilized healthcare delivery pathway by TRD patients.

Background

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a psychiatric mood disorder characterized by disabling and chronic depression as well as lack of enjoyment in previously enjoyable activitiesCitation1. In 2016, MDD was estimated to annually affect over 16 million Americans and its economic burden was estimated to exceed $210 billion in 2010Citation2,Citation3. Although antidepressant (AD) therapies are available for patients with MDD, only 53.1% of patients receive treatmentCitation4. Among those who do receive treatment, one in three patients with MDD experience treatment-resistant depression (TRD), which is defined as MDD that persists despite two different AD regimens of adequate dose and durationCitation5–9.

The difficulties associated with caring for patients with TRD have contributed to its substantial economic burden and healthcare resource use (HRU)Citation10. To overcome this burden, a number of interventions have been proposedCitation11–14. For example, home health services (HHS) have been recommended as a way to provide mental health services and improve mental health outcomes particularly within the context of better coordination between care settingsCitation14. HHS represents a healthcare delivery pathway intended to reduce the risk of disease progression as many patients are unable or refuse to receive treatment in outpatient settingsCitation12. Indeed, a major benefit of HHS is the opportunity for patients to receive treatment from the comfort of their homeCitation15.

Although HHS has the potential to benefit patients with TRD, it is often cited within the context of elder care, recovery from physical injury, and occupational services; less is known regarding HHS use among MDD patients with and without TRD. To help fill this gap in knowledge, the goal of this study was to describe HHS use among three cohorts of commercially insured patients: those with TRD (TRD cohort), patients with MDD who did not meet the criteria for TRD (non-TRD MDD cohort), and patients without MDD (non-MDD cohort). In addition, this study aimed to characterize the use of other healthcare services overall and within each cohort, stratified by HHS use.

Methods

Data source

This study used health claims data from the OptumHealth Care Solutions, Inc. database (July 2009–March 2015). The database includes medical and pharmacy claims for over 19 million privately insured employees and their dependents throughout the United States. Information contained in the database includes patient demographics (e.g. age, gender, region), enrollment history, medical diagnoses, prescription drug use (e.g. fill dates, national drug codes, and payment history). Data for short- and long-term disability claims were available for a subset of patients. Data are de-identified and compliant with the patient confidentiality requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. No ethics board review was required.

Study design, sample selection, and study cohorts

This retrospective longitudinal design consisted of three mutually exclusive patient cohorts: TRD, non-TRD MDD, and non-MDD.

For the TRD and non-TRD MDD cohorts, patients were required to meet the following criteria: (1) at least one diagnosis for MDD (International Classification of Disease Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes: 296.2x (MDD – single episode), 296.3x (MDD – recurrent episode)); (2) at least one claim for an AD between 1 January 2010 and 31 March 2015 (defined as the index date) and no AD claims in the 6 months prior; (3) at least one diagnosis for depression (ICD-9-CM: 296.2x, 296.3x, 300.4x, 311.x, 309.0x, or 309.1x) within the 6 months prior to or after the index date; (4) have claims for at least one AD with an adequate dose, defined as the minimum starting dose based on treatment guidelines from the American Psychiatric AssociationCitation6 and duration (i.e. at least 6 weeks of continuous therapy with gaps no longer than 14 days) following the index date.

The TRD cohort included patients with MDD who experienced two failed AD treatment regimens (including augmentation therapy with anticonvulsant, anxiolytic, antipsychotic, lithium, psychostimulant, and thyroid hormone medications) with adequate dose and duration. Failure of a treatment course was defined as a switch of an AD (no more than 180 days after the end of the previous treatment), the addition of an AD, or the initiation of an augmentation therapy. Initiation of a third AD or augmentation medication defined TRD, consistent with recent literature using insurance claims databases to identify patients with TRDCitation10,Citation16–22.

The non-TRD MDD cohort included patients with MDD who did not meet the criteria for TRD at any time during the two years following the index date. The non-MDD cohort comprised a randomly selected sample of 500,000 patients without an MDD diagnosis between 1 July 2009 and 31 March 2015, among whom the index date was randomly assigned.

Patients in the TRD, non-TRD MDD, and non-MDD cohorts were required not to have a diagnosis for the following psychiatric comorbidities: psychosis (ICD-9-CM code: 298.xx), schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM code: 295.xx), bipolar disorder/manic depression (ICD-9-CM codes: 296.0x, 296.1x, 296.4x, 296.5x, 296.6x, 296.7x, and 296.8x), dementia (ICD-9-CM code: 290.xx or 294.1x) between 1 July 2009 and 31 March 2015. Additionally, patients were required to be 18–64 years old on the index date; have no Medicare coverage between 1 July 2009 and 31 March 2015; ≥6 months of continuous eligibility prior to the index date (baseline period); ≥6 months of continuous eligibility after the index date. Outcomes were evaluated from the index date up until 2 years post-index date, the end of continuous eligibility or the end of data availability.

Study cohorts were stratified by HHS use, which was defined by the presence of a medical claim with ≥1 of the following codes during the observation period: home-related procedure codes for home health procedures and services, home services or in home nursing care (i.e. Current Procedural Terminology codes: 99500–99602 and 99341–99350, and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes: S9122–S9124, T1001–T1004, T1021, T1030 and T1031), or a claim with “Patients’ home” as the place-of-service code, “Home health agency” or “home health aide” as the provider type code, “Home health aide” as the provider specialty code, and “Home care” as the type-of-service code.

Study measures and analyses

Baseline characteristics among cohorts included demographics (e.g. age, gender, region, type of healthcare plan), physical and mental comorbidities, and use of healthcare pathways other than HHS in patients with TRD, non-TRD MDD, and non-MDD.

All-cause and mental health-related HRU (i.e. inpatient visits, inpatient days, emergency department visits, outpatient visits, other visits, and HHS) and healthcare costs (i.e. inpatient, emergency department, outpatient, other, and HHS) were measured per-patient-per-year (PPPY). Costs of payers were reported in 2015 US dollars. Study outcomes were measured for each cohort and further stratified by HHS use (i.e. with vs. without HHS).

Indirect work loss-related days and costs (i.e. the number of total work loss days, medical-related absenteeism, and disability days determined based on days of absenteeism and wages) were calculated only among employees who had work-loss information available.

Patient characteristics and study measures were evaluated using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were assessed using means, medians, and standard deviations; frequencies and percentages were used to assess categorical variables. No statistical comparisons were made between cohorts.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 6411 TRD patients (with HHS: 1152; without HHS: 5259), 33,068 non-TRD MDD patients (with HHS: 4084; without HHS: 28,984), and 149,884 non-MDD patients (with HHS: 9743; without HHS: 140,141) were included in this study (). A considerable proportion of patients (18.0%) in the TRD cohort received HHS during the 2-year follow up, while 12.4% of non-TRD MDD and 6.5% of non-MDD patients were HHS users. Among all three cohorts, patients with HHS had a mean age of 45.0–47.2 years while patients without HHS had a mean age of 39.5–42.0 years. Patients who used HHS had a mean Quan-Charlson Comorbidity Index (Quan-CCI)Citation23 ranging from 0.5 to 0.6, while patients who did not use HHS had a mean Quan-CCI ranging from 0.1 to 0.2, indicating that patients who used HHS had a numerically higher level of comorbidities. Among HHS users, the most commonly reported physical comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes, and chronic pulmonary disease; the most commonly reported mental health-related comorbidities included depression, anxiety, and sleep-wake disorders.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics, HRU, and healthcare costs stratified by cohort and by HHSTable Footnotea use.

Most common healthcare delivery pathways

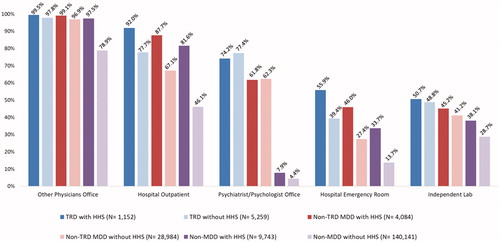

The most commonly used healthcare delivery pathways based on place of service codes, irrespective of HHS use, included other physicians’ office, hospital outpatient, psychiatrist/psychologist office, hospital emergency room, and independent laboratory (). In general, a higher proportion of patients with HHS utilized different healthcare delivery pathways irrespective of the cohort.

All-cause and mental health-related HRU and costs stratified by HHS use

Of the TRD patients receiving HHS during the follow-up, nearly 25% used HHS at baseline. Among HHS users, the rates of all-cause HHS visits PPPY were 4.55 in the TRD cohort, 3.89 in the non-TRD MDD cohort, and 3.41 in the non-MDD cohort (). Costs for HHS represented a relatively small proportion of total healthcare costs: $1419 (3.5%) for the TRD cohort, $1175 PPPY (4.1%) for the non-TRD MDD cohort, and $1223 PPPY (5.5%) for the non-MDD cohort (). Mean all-cause healthcare costs PPPY were numerically higher for patients with HHS use across all three cohorts. Among the TRD cohort, patients using HHS had healthcare costs of $40,040 PPPY while patients with TRD and no-HHS had healthcare costs of $12,272 PPPY. Within the non-TRD MDD cohort, HHS users incurred healthcare costs of $28,767 PPPY and non-HHS users incurred costs of $7227 PPPY. Patients without MDD who used HHS had healthcare costs of $22,340 PPPY while non-MDD patients who did not use HHS had healthcare costs of $3479 PPPY ().

Figure 2. Healthcare costs (the observation period was restricted to a maximum of 2 years following index date (all patients were required to have an observation period of at least 6 months)) in the TRD cohort, the unmatched non-TRD MDD, and non-MDD cohorts, stratified by HHS use (use of HHS was identified during the 24 months following index date, based on place of service, provider type and relevant procedure codes). Abbreviations. ED, Emergency department; HHS, Home health services; MDD, Major depressive disorder; PPPY, Per-patient-per-year; TRD, Treatment-resistant depression; US, United States.

Table 2. Follow-up direct HRU and days of work loss in the TRD cohort, the non-TRD MDD, and non-MDD cohorts, stratified by HHS useTable Footnotea.

Table 3. Follow-up direct and indirect healthcare costs in the TRD cohort, the non-TRD MDD, and non-MDD cohorts, stratified by HHS useTable Footnotea.

In the TRD and non-TRD MDD cohorts, mental health-related services contributed a smaller percentage of overall healthcare costs among HHS users. In the TRD cohort, among HHS users’ mental health-related services represented 23.8% of total healthcare costs while among non-HHS users 42.0% of healthcare costs were mental health-related. Among patients in the non-TRD MDD cohort, 18.4% of HHS users’ healthcare costs were mental-health related while 28.9% of non-HHS users’ healthcare costs were mental-health related. Mental health services contributed a similar percentage of the overall healthcare costs among HHS and non-HHS users in the non-MDD cohort (4.8%).

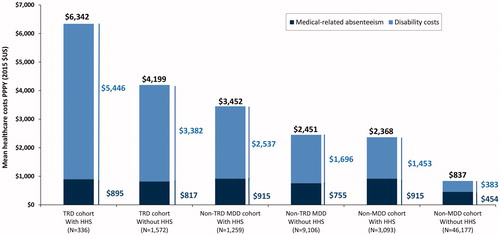

Among employees with available work-loss data, overall costs were largely driven by disability-related costs; patients with TRD had the numerically highest total work loss-related indirect costs PPPY regardless of HHS use, with a larger proportion of these costs being mental health-related. A higher percentage of mental health-related indirect costs contributed to the overall indirect cost burden for non-HHS users relative to HHS users. Among HHS users, these all-cause costs and the proportion that was mental health-related amounted to $6342 (43.5%) in the TRD cohort, $3452 (24.0%) in the non-TRD MDD cohort, and $2368 (2.8%) in the non-MDD cohort. Among non-HHS users, these all-cause costs and the proportion that was mental health-related amounted to $4199 (56.2%) in the TRD cohort, $2451 (48.0%) in the non-TRD MDD cohort, and $837 (5.0%) in the non-MDD cohort (). Mean all-cause work loss days PPPY were higher for patients with HHS use across all three cohorts (TRD cohort: 50.7 vs. 34.6; non-TRD MDD cohort: 35.0 vs. 19.5; non-MDD cohort: 19.7 vs. 5.1) ().

Figure 3. Work-loss costs (the observation period was restricted to a maximum of 2 years following index date (all patients were required to have an observation period of at least 6 months)) in the TRD cohort, the unmatched non-TRD MDD, and non-MDD cohorts stratified by HHS use (use of HHS was identified during the 24 months following index date, based on place of service, provider type and relevant procedure codes). Abbreviations. HHS, Home health services; MDD, Major depressive disorder; PPPY, Per-patient-per-year; TRD, Treatment-resistant depression; US, United States.

Discussion

This retrospective claims-based analysis adds valuable insight regarding the use of HHS among three mutually exclusive cohorts of patients: those with TRD (TRD), those without TRD (non-TRD MDD), and patients without MDD (non-MDD). Although most of the literature to date has focused on HHS use among older, homebound adults over the age of 65 yearsCitation24–28, the algorithm to identify HHS use in the present study was based on place of service, provider type, and relevant procedure codes, which created a more inclusive definition for identifying HHS users and HHS, thereby adding valuable insight regarding its use. The inclusion of adults aged 18–64 years and the finding that nearly 20% of patients with TRD used HHS suggests that HHS is an acceptable healthcare delivery model among younger adults, as well as the elderly.

Results of this analysis revealed that 18.0% of patients with TRD used HHS while 12.4% of patients in the non-TRD MDD cohort and 6.5% of patients in the non-MDD cohort used HHS. HHS-related HRU and costs, both direct and indirect, were numerically higher within the TRD cohort. Across all cohorts, HHS users had longer observation periods and overall numerically higher all-cause HRU, with inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, and other visits being numerically more frequent among patients who used HHS. Similar findings were generally observed for mental health-related HRU, with the exception of mental health-related outpatient visits. Patients who used HHS incurred 3–4 times numerically higher costs than patients without HHS use. However, HHS accounted for only 3.5–5.5% of total healthcare expenditures. Mental health-related costs accounted for a minority of total healthcare costs across all cohorts, suggesting that the difference between the costs of HHS and non-HHS users may be largely attributed to physical comorbidities. Overall, the results of this study suggest a great unmet need among patients with TRD who utilize HHS.

HHS users had consistently numerically higher HRU and costs; however, a notable exception was mental health-related outpatient visits, which were more common among non-HHS users in the TRD and non-TRD MDD cohorts. Three non-mutually exclusive explanations that may account for this observation include (1) the possibility that the lower rate of outpatient visits among HHS users with MDD may be a consequence of frequent use of more expensive inpatient and emergency department visits; (2) that HHS use may reduce the need for outpatient visits; and (3) that HHS patients face barriers to non-urgent healthcare visits. Although HHS users had numerically higher costs, the contribution of HHS to the overall costs across all cohorts was marginal, which suggests HHS may be a cost-effective delivery pathway for patients with TRD or non-TRD MDD. This finding aligns with previous reports regarding the potential of HHS to reduce costly inpatient and emergency department visits in patients with depressionCitation27, or other chronic conditionsCitation29–31.

Of interest was the finding that a small percentage of mental health-related costs contributed to the overall all-cause healthcare cost burden among all three cohorts, specifically among patients that used HHS. Additionally, patients in the TRD and non-TRD MDD cohorts who did not use HHS had slightly higher percentages of mental health-related costs that contributed to their all-cause healthcare burden. In a previous study, it was reported that mental health-related costs accounted for 38% of all-cause costs in patients with MDDCitation3, which is consistent with the 42% of all-cause costs reported in this study. The current study builds upon previous findings by evaluating the contribution of physical comorbidity costs in HHS and non-HHS users, and in patients with TRD and non-TRD MDD. Although not explicitly tested, it is possible that physical comorbidities are likely to act as major drivers of cost differences between HHS and non-HHS users.

Several studies have reported the positive impact of community-based mental health programs and home-based servicesCitation11,Citation26,Citation32. For example, results from the CAREPATH trial, reported a significant difference in favor of home-based services among patients with moderate-to-severe depressionCitation26. However, important challenges need to be addressed in order to improve the utility of HHS within the general context of depression care, most notably, challenges related to the successful implementation of HHS programs. A 2015 study conducted by Bao et al. reported that implementation-related challenges include the perception of many HHS nurses that depression care is outside the scope of their practice, knowledge gaps regarding the roles of different team members in depression care (e.g. nurses, social workers, etc.), restrictions due to eligibility criteria, depression-related stigma, and poor communication between HHS team members and primary care cliniciansCitation33. Despite these challenges, HHS nurses possess the clinical skills needed to assess depression, to initiate treatment, and follow-up with the patient and their other care providersCitation32.

Successful implementation of HHS programs within the context of depression care could potentially help alleviate challenges that pertain to the efficacy of prescribed medications. For example, commonly used ADs are often prescribed at sub-therapeutic dosesCitation24,Citation33 and standard ADs can take several weeks before producing a noticeable reduction in symptomsCitation25. Such delays have the potential to negatively affect patients’ attitudes toward their medication, which can contribute to reductions in compliance and adherence to therapyCitation25. In light of the changing treatment landscape for TRD and MDD with the development of novel therapies for patients with unmet medical needsCitation34, HHS has the potential to help patients, particularly those with TRD, successfully transition into newly developed therapeutic regimens that may be well-served within the context of an HHS.

Limitations

The findings reported in this study should be interpreted within the context of certain limitations. First, the data presented in this study are descriptive and were not adjusted for potential confounders and the impact of such confounders on the results is unknown. Future research evaluating cost and HRU differences among patients with versus without HHS use while controlling for potential confounders are warranted. Second, TRD exists along a clinical continuum and does not have a consensus definition; however, the current study has used the most common definition of TRD, which relies on pharmacy claims and cannot incorporate other clinical considerations or patient-reported outcomes to assess treatment failure, response, and remission. Third, as with all claims-based studies, analyses are subject to the possibility of inherent limitations related to inaccuracies due to coding errors and missing data. Finally, this study focused on commercially insured employees and their dependents; therefore, findings may not be generalizable to the overall population of patients with non-TRD MDD and/or TRD.

Conclusions

This study found that patients with TRD have numerically higher healthcare resource use and costs relative to non-TRD MDD and non-MDD patients. HHS use was most common within the TRD cohort with approximately one in five privately insured TRD patients using HHS. The small contribution of mental health-related costs among HHS users compared to the overall healthcare costs and higher comorbidity burden suggests that physical comorbidities may be key drivers of HHS utilization. Taken together, the results of this study demonstrate that HHS is a healthcare pathway that is currently utilized among patients with TRD; however, services are not primarily used to treat TRD. This suggests that there may be an opportunity for HHS nurses to provide treatment for TRD in conjunction with services for physical comorbidities, which may result in a more individualized and integrated care plan for patients with TRD. Additional work is needed to explore the potential of HHS in delivering behavioral health services and reducing the high burden of healthcare costs and resource use among patients with TRD.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The study sponsor was involved in all stages of the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and in writing the manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

DP, LM, and PL are employees of Analysis Group Inc., which received consultancy fees from Janssen Scientific for the conduct of this study. At the time this study was conducted, DS was an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. HS and JJS are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC and may own Johnson & Johnson stock/stock options. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from CMRO for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

DP, HS, DS, LM, JJS, and PL contributed to the conception and design of the study, analyses, interpretation of data, as well as drafting of the manuscript for publication. All authors have approved the final manuscript

Previous presentations

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists 2018 Summer Meetings and Exhibition (ASHP) held on 2–6 June 2018 in Denver, Colorado, USA.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Data are de-identified and compliant with the patient confidentiality requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. No ethics board review was required.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Gloria DeWalt, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc. Support for this assistance was provided by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from OptumHealth Care Solutions, Inc. but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and are not publicly available.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Facts and statistics; 2018 [cited 2018 Jun 21]. Available from: https://adaa.org/about-adaa/press-room/facts-statistics.

- Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(02):155-162.

- Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Meyers JL, et al. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psych. 2018;75(4):336-346.

- Kubitz N, Mehra M, Potluri RC, et al. Characterization of treatment resistant depression episodes in a cohort of patients from a US commercial claims database. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76882.

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder third edition; 2010 [cited 2018 Jun 27]. Available from: https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Major depressive disorder: developing drugs for treatment (guidance for industry); 2018 [cited 2018 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM611259.pdf.

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products in the treatment of depression; 2013 [cited 2018 Jul 25]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2013/05/WC500143770.pdf.

- Gaynes BN, Asher G, Gartlehner G, et al. Definition of treatment-resistant depression in the medicare population; 2018 [cited 2018 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coverage/DeterminationProcess/downloads/id105TA.pdf.

- Amos TB, Tandon N, Lefebvre P, et al. Direct and indirect cost burden and change of employment status in treatment-resistant depression: a matched-cohort study using a US Commercial Claims Database. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(2). doi:10.4088/JCP.17m11725

- Barnett ML, Gonzalez A, Miranda J, et al. Mobilizing community health workers to address mental health disparities for underserved populations: a systematic review. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2018;45(2):195-211.

- Reifler BV, Bruce ML. Home-based mental health services for older adults: a review of ten model programs. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(3):241-247.

- Dixon LB, Holoshitz Y, Nossel I. Treatment engagement of individuals experiencing mental illness: review and update. World Psych. 2016;15(1):13-20.

- RARE Mental Health Work Group. Recommended actions for improved care transitions: mental illnesses and/or substance use disorders; 2018 [cited 2018 May 10]. Available from: http://www.rarereadmissions.org/documents/Recommended_Actions_Mental_Health.pdf.

- West-Bey N, Cosse R, Schmit S. Maternal depression and young adult mental health: policy agenda for systems that support mental health and wellness; 2018 [cited 2018 Jun 19]. Available from: https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/publications/2018/02/2018.02.12%20Maternal%20Depression%20YA%20MH%20report.pdf.

- Pilon D, Szukis H, Joshi K, et al. US integrated delivery networks perspective on economic burden of patients with treatment-resistant depression: a retrospective matched-cohort study. Pharmacoecon Open. 2019.

- Pilon D, Sheehan JJ, Szukis H, et al. Medicaid spending burden among beneficiaries with treatment-resistant depression. J Comp Eff Res. 2019;8(6):381-392.

- Pilon D, Sheehan JJ, Szukis H, et al. Is clinician impression of depression symptom severity associated with incremental economic burden in privately insured US patients with treatment resistant depression? J Affect Disord. 2019;255:50-59.

- Pilon D, Joshi K, Sheehan JJ, et al. Burden of treatment-resistant depression in Medicare: a retrospective claims database analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223255.

- Szukis H, Benson C, Huang A. Economic burden of illness among us veterans with treatment-resistant depression. Poster presented at: US Psych Congress; 2018 Oct 25–28; Orlando, FL.

- Benson C, Szukis H, Sheehan JJ, et al. An evaluation of the clinical and economic burden among older adult medicare-covered beneficiaries with treatment-resistant depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. [cited 2019 Oct 22]. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2019.10.012.

- Li G, Fife D, Wang G, et al. All-cause mortality in patients with treatment-resistant depression: a cohort study in the US population. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2019;18(1):1-8.

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139.

- Bruce ML, McAvay GJ, Raue PJ, et al. Major depression in elderly home health care patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(8):1367-1374.

- Bruce ML, Raue PJ, Sheeran T, et al. Depression care for patients at home (depression CAREPATH): home care depression care management protocol, part 2. Home Healthc Nurse. 2011;29(8):480-489.

- Bruce ML, Raue PJ, Reilly CF, et al. Clinical effectiveness of integrating depression care management into medicare home health: the Depression CAREPATH Randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(1):55-64.

- Markle-Reid M, McAiney C, Forbes D, et al. An interprofessional nurse-led mental health promotion intervention for older home care clients with depressive symptoms. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14(1):62.

- Shao H, Peng TR, Bruce ML, et al. Diagnosed depression among Medicare home health patients: national prevalence estimates and key characteristics. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(5):538-540.

- Alkema GE, Wilber KH, Shannon GR, et al. Reduced mortality: the unexpected impact of a telephone-based care management intervention for older adults in managed care. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1632-1650.

- Macinko J, Dourado I, Aquino R, et al. Major expansion of primary care in Brazil linked to decline in unnecessary hospitalization. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(12):2149-2160.

- Prior MK, Bahret BA, Allen RI, et al. The efficacy of a senior outreach program in the reduction of hospital readmissions and emergency department visits among chronically ill seniors. Soc Work Health Care. 2012;51(4):345-360.

- Groh CJ, Dumlao MS. Depression in home-based care: the role of the home health nurse. Home Healthc Now. 2016;34(7):360-368.

- Bao Y, Eggman AA, Richardson JE, et al. Practices of depression care in home health care: home health clinician perspectives. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(12):1365-1368.

- Singh JB, Fedgchin M, Daly E, et al. Intravenous esketamine in adult treatment-resistant depression: a double-blind, double-randomization, placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(6):424-431.