Abstract

Objective: To compare the rates of successfully treated patients (STPs) with vortioxetine versus venlafaxine in major depressive disorder (MDD), using dual endpoints that combine improvement of mood symptoms with optimal tolerability or functional remission, and conduct a simplified cost-effectiveness analysis.

Methods: The 8-week SOLUTION study (NCT01571453) assessed the efficacy and safety of vortioxetine (10 mg/day) versus venlafaxine XR (150 mg/day) in adult Asian patients with MDD. Rates were calculated post-hoc of STP Mood and Tolerability (≥50% reduction from baseline in Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale [MADRS] total score and no treatment-emergent adverse events) and STP Mood and Functioning (≥50% reduction from baseline in MADRS total score and Sheehan Disability Scale total score ≤6). The incremental costs per STP were assessed using the 2018 pharmacy purchase prices for branded vortioxetine/branded venlafaxine in China as the base case.

Results: STP Mood and Tolerability rates were 28.9% for vortioxetine and 19.9% for venlafaxine (p = .028); the corresponding STP Mood and Functioning rates were 28.0% and 23.5% (p = .281). Drug costs for the 8-week treatment period were CN¥1954 for vortioxetine and CN¥700 for venlafaxine. The incremental cost per STP for vortioxetine versus venlafaxine was CN¥13,938 for Mood and Tolerability and CN¥27,876 for Mood and Functioning.

Conclusions: Higher rates of dual treatment success were seen with vortioxetine versus venlafaxine. Although vortioxetine was not dominant in the base case, the incremental cost per STP for vortioxetine versus venlafaxine were overall within acceptable ranges. These results support the benefits previously reported with vortioxetine versus other antidepressants in broad efficacy, tolerability profile and cost-effectiveness.

Introduction

Depression is a prevalent and debilitating illness estimated to affect 4.2% of the Chinese populationCitation1. The high prevalence and seriousness of the illness are reflected in the high burden of disease associated with major depressive disorder (MDD), globally and in ChinaCitation1. The overall negative impact of depression – individual, societal, and economic – may be exacerbated by low disease awareness and social stigma associated with mental illness, as well as limitations in mental health care resources, leading to underreporting, underdiagnosis and insufficient treatment of mental illnesses such as depressionCitation2–4.

Criteria for antidepressant treatment success typically focus on improvement of depressive mood symptoms as defined by remission or recovery according to improvement or threshold scores on depression rating scalesCitation5. However, side effects during antidepressant treatment are a common problem, reported in one study by as many as 86% of patients treated with an SSRICitation6. Tolerability issues may not only counteract treatment success by negatively affecting patients’ overall treatment experience and cause patients to discontinue their treatment thus increasing the risk of relapse; treatment side effects may per se affect patient functioning and add to the distress associated with the illnessCitation7,Citation8. Therefore, models assessing the overall benefits associated with treatment should weigh symptomatic efficaciousness against tolerability issues to obtain a full picture of both the patient and the cost perspectiveCitation9–11.

Further, full recovery from depression encompasses multiple dimensions beyond symptom resolution, with patients’ functional capacity, such as ability to work or participate in daily family life and social activities, as a key element of full recoveryCitation12. Hence, not all patients who meet formal remission criteria consider themselves in remission, and these patients further report poorer functioning than patients who do consider themselves in remissionCitation12. Likewise, residual psychosocial impairment has been shown to predict relapseCitation13–15. More broadly defined treatment outcomes that integrate minimal side effects or patient functioning with improvement of mood symptoms may more accurately reflect treatment priorities from a patient perspective, better capture the complex of adversity associated with depression and broaden the focus to full functional recovery as the treatment goalCitation16–18.

The objective of this exploratory study was twofold: first, to compare the rates of successfully treated patients with vortioxetine versus venlafaxine extended release (XR) using two definitions for treatment success that capture benefits in addition to symptomatic improvement, namely minimal tolerability problems and functional remission; second, to use this information to conduct a simplified cost-effectiveness analysis from a Chinese perspective (base case). Vortioxetine is a serotonin (5-HT)3, 5-HT7 and 5-HT1D receptor antagonist, a 5-HT1B receptor partial agonist, a 5-HT1A receptor agonist, and a serotonin transporter inhibitor that has demonstrated robust antidepressant efficacy and a favorable tolerability profile across different patient populationsCitation19–21. Venlafaxine XR, a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), was used as a comparator because it is an efficacious and well tolerated antidepressant commonly used in China, with a different mode of action from vortioxetineCitation22,Citation23.

Methods

This study is based on data from the SOLUTION study (www.ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier: NCT01571453), a randomized, double-blind, 8-week fixed-dose study designed to assess the efficacy and safety of vortioxetine in Asian patients with MDD head-to-head versus an active comparator (venlafaxine XR). The methodology and primary efficacy and safety results of the SOLUTION study are described in detail elsewhereCitation24.

The study included Asian outpatients aged 18 to 65 years, predominantly Chinese, with a primary diagnosis of recurrent MDD (per DSM-IV) and a current major depressive episode (MDE) of more than 3 months’ duration, a Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score of ≥26, and a Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) score of ≥4. The study excluded patients with any current psychiatric disorder other than MDD, a history of manic or hypomanic episodes, schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders, or any substance abuse disorder within the previous 2 years, as well as patients at risk of suicide. Patients not responding to treatment with venlafaxine for the present or a previous depressive episode were also excluded, as were patients with uncontrolled hypertension, elevated risk of serious cardiac ventricular arrhythmia or acute narrow-angle glaucoma, in accordance with the safety recommendation for venlafaxine XRCitation24.

Eligible patients were randomized with a ratio of 1:1 to 8 weeks of double-blind treatment with vortioxetine (10 mg/day) or venlafaxine XR (150 mg/day), followed by 1 week of down-tapering during which period the vortioxetine group received placebo and the venlafaxine XR group received 75 mg/day. A safety follow-up was conducted 4 weeks after study completion. The study was conducted at a total of 31 psychiatric sites in China, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand from April 2012 to October 2013.

Assessments

Efficacy and safety assessments were conducted at baseline and weeks 1, 2, 4, 6 and 8. Severity of mood symptoms were assessed using the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)Citation25, a 10-item clinician-reported rating scale assessing depressive symptom severity. MADRS total score (possible score range 0–60) was calculated as the sum of scores on single items, with higher scores indicating worse symptom severity. Patient functioning was assessed using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS)Citation26 comprising three 10 point visual analogue scales on which patients rate the extent to which depressive symptoms impair their: i) work, ii) social life or leisure activities, and iii) family life or home responsibilities. The total score (possible score range 0–30) is calculated as the sum of scores on the three subscales, with higher scores indicating higher level of functional impairment. For non-working patients, the work dimension score was imputed as the average of social life and family life dimension scores, and the total score subsequently computed using the imputed work dimension score.

Adverse events (including worsening of concurrent disorders, new disorders and pregnancies) and their intensity (mild, moderate or severe) as well as relation to the treatment were recorded at each visit by the clinician based on a non-leading question (for example, “how do you feel?”), clinical observation or spontaneous patient reporting.

Statistical analysis

Analyses of successfully treated patients (STPs) comprised all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study medication (treated patients; for details on per protocol analysis setsCitation24). Post-hoc study endpoints assessed the percentages at week 8 of STPs (last observation carried forward, LOCF), according to two dual treatment outcomes: a) symptomatic response without compromised tolerability (STP Mood and Tolerability), defined as ≥50% reduction from baseline in MADRS total score and no reported treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs; i.e. adverse event that began on or after the date of first dose of drug and before the last visit); and b) symptomatic response and functional remission (STP Mood and Functioning), defined as ≥50% reduction from baseline in MADRS total score and SDS total score ≤6. Reported p values for the difference between vortioxetine and venlafaxine XR are based on chi-squared tests.

Costs per STP according to each of the dual treatment outcomes defined above were calculated for an 8-week treatment period as the base case. Cost-effectiveness is presented as the incremental cost per additional STP for vortioxetine versus venlafaxine XR, calculated as the difference in costs for the treatments across the treatment period divided by the difference in proportions of STPs in the treatment groups. Average drug costs for the 8-week treatment period were calculated based on the pharmacy purchase prices in China, Q1 2019 in Chinese Yuan Renminbi (CN¥) for branded vortioxetine (Brintellixi), branded venlafaxine (Effexorii) and generic venlafaxine. Discounting was not applied because of the short time-span (8 weeks).

Clinical sensitivity analyses for different definitions for STPs comprised using single definitions: i) No TEAEs; ii) ≥50% reduction in MADRS total score; iii) SDS total score ≤6; iv) using a stricter definition of the symptomatic treatment outcome with a common remission threshold of MADRS total score <10, v) using a definition of Mood and Tolerability with no moderate or severe TEAEs thus disregarding AEs that could have less clinical impact; and vi) extrapolation of results for a 6-month treatment period. Further, sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact on the results of using regional prices (branded and generic venlafaxine XR) for Taiwan, USA, UK and Brazil.

Treatment outcomes were analyzed using SAS, Version 9.4 statistical software, and cost-effectiveness analyses using MS Excel.

Results

Treatment outcome and cost-effectiveness analyses included 211 patients treated with vortioxetine and 226 treated with venlafaxine XR, of whom approximately 60% were Chinese (). The sample mean age was 40 years, and approximately 60% were women. The mean baseline MADRS total score was 32, indicating moderate to severe depression, and the mean duration of the current MDE was approximately 30 weeks. There were no notable differences between the treatment groups in demographic or baseline clinical characteristics. See Wang et al.Citation24 for full details.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical sample characteristics.

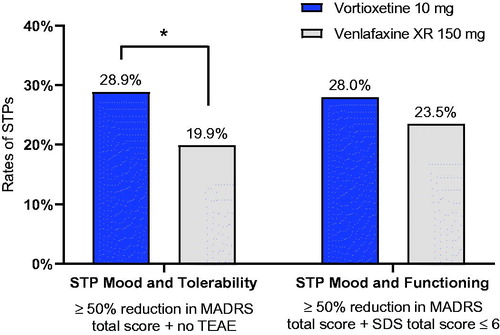

After 8 weeks of treatment, the rates of STPs were higher in the vortioxetine group compared with the venlafaxine XR group, both for STPs as defined by Mood and Tolerability criteria (28.9% for vortioxetine versus 19.9% for venlafaxine; p = .028) and by Mood and Functioning criteria (28.0% for vortioxetine versus 23.5% for venlafaxine XR; p = .281), .

Figure 1. Successfully treated patients (STPs) at week 8 by treatment group.

*p < .05. Treated patients; last observation carried forward. STP Mood and Tolerability: vortioxetine n = 61/211; venlafaxine, n = 45/226; STP Mood and Functioning: vortioxetine n = 59/211; venlafaxine, n = 53/226.

Abbreviations. MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; STP, Successfully treated patient; TEAE, Treatment-emergent adverse event; XR, Extended release.

For the single STP dimensions, 139 (65.9%) patients treated with vortioxetine and 132 (58.4%) treated with venlafaxine showed symptomatic response, while 64 (30.3%) and 58 (25.7%) patients in the respective treatment arms were in functional remission. Among patients treated with vortioxetine, 83 (39.3%) reported no TEAEs, whereas this was the case for 69 (30.5%) patients treated with venlafaxine; the corresponding numbers of patients reporting no moderate or severe TEAEs were 177 (83.9%) and 158 (69.9%) for the respective treatments. For both dual STP outcomes, the rates of patients who met criteria for treatment success on only one of the individual dimensions were comparable (Supplementary Figure).

The estimated base case drug costs for the 8-week treatment period in China were CN¥1954 for branded vortioxetine 10 mg/day and CN¥700 for branded venlafaxine 150 mg/day (). The mean costs per STP were higher for vortioxetine than for venlafaxine XR and less so for Mood and Tolerability (difference = CN¥3245) than for Mood and Functioning (difference = CN¥4002). The incremental cost per additional STP for vortioxetine versus venlafaxine XR was CN¥13,938 per STP Symptoms and Tolerability and CN¥27,876 per STP Mood and Functioning.

Table 2. Summary of drug costs, treatment outcomes and base case results.

Across the sensitivity analyses of clinical outcomes using single definitions for STPs, a threshold for mood of MADRS total score <10 (remission), considering only moderate and severe TEAEs in the definition STP Mood and Tolerability, and a 6-month time horizon, the numerical rates of STPs were consistently higher with vortioxetine than with venlafaxine XR ().

Table 3. Clinical sensitivity results.

Across region sensitivity analyses (Taiwan, US, UK, Brazil), vortioxetine was dominant versus branded venlafaxine XR (). Using generic prices for venlafaxine XR, the incremental costs per STP Mood and Tolerability with vortioxetine versus venlafaxine XR ranged from US$128 (Brazil) to US$5196 (US) and from US$256 (Brazil) to US$10,391 (US) for STP Mood and Functioning.

Table 4. Region sensitivity results, brand and generic prices.

Discussion

In this study, significantly more patients were treated successfully with vortioxetine compared with venlafaxine XR when assessing symptomatic response in combination with either optimal tolerability or functional remission. Particularly, these results support the favorable tolerability and benefit–risk profile of vortioxetine relative to other antidepressants that has previously been reportedCitation9,Citation10,Citation20,Citation27,Citation28. The results further corroborate previous findings that vortioxetine, in addition to effectively treating mood symptoms, has a broader effect on overall patient functioningCitation29. This might be related to the multimodal mode-of-action of vortioxetine with documented effects on cognitive performanceCitation30,Citation31, which have been proposed as a mediator of functional treatment outcomesCitation32,Citation33. The comparable rates of patients who met criteria for treatment success on only one of the individual dimensions confirmed that these results could be attributed to treatment differences for the dual criteria and were not driven by any of the individual dimensions.

The concept of STPs has previously been applied in a cost-effectiveness study in diabetesCitation34; only a few previous studies, however, have used composite approaches to assess treatment outcomes in MDDCitation35,Citation36. Although the STP definitions used in this study are thus novel, they are based on consensus thresholds for MADRS response and SDS remissionCitation37,Citation38. The importance of early response and functional remission for long-term prognosis is well established, as is the importance of risk–benefit balance via improved adherence to treatment and treatment satisfactionCitation8,Citation39–41, supporting that broader outcomes beyond symptomatic improvement may more accurately reflect the real-world clinical benefit of treatment than a single dimension in isolation.

Although vortioxetine did not dominate in the base case of this study versus venlafaxine XR (which has been on the Chinese market since 2000), vortioxetine consistently dominated versus branded venlafaxine XR across region sensitivity analyses. In previous economic evaluations, vortioxetine has shown dominance versus venlafaxine XR in South KoreaCitation42, versus duloxetine in NorwayCitation43, and as a second-line therapy (versus agomelatine, bupropion, venlafaxine and sertraline) in FinlandCitation44. It should be noted that the cost-effectiveness model applied in this study was based on units of STPs rather than health-economic standard effect measures such as quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) or disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)Citation45. While the results from this cost-effectiveness analysis are therefore not directly comparable to those obtained from QALY-based analyses, which remain the gold standard for cost–utility analyses, the concept of STP may serve as a supplement to more elaborate models, as it is both simpler and intuitively meaningful from a clinical standpoint, and therefore accessible for a broader audience beyond health economic experts.

It should also be noted that conventional thresholds for the “acceptability” for HTA (Health Technology Assessment) authorities of the incremental costs of one treatment relative to another are also typically based on the QALY as the unit of health gain. Thus, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) operates with an upper threshold of £30,000 (US$39,900) per QALYCitation46 while a threshold of US$50,000/QALY is commonly cited for the USCitation45; this threshold, being cited since 1982, may be considered conservative as a current thresholdCitation45. An alternative approach based on country Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as reference, is used by the World Health Organization (WHO) defining a threshold of three times GDP per capita per DALYCitation45,Citation47. While the QALY is a generic metric composed of a broad range of information, the STP is specifically defined in the context of depression, which limits the applicability of QALY-based thresholds to the cost estimates of this study. Bearing this limitation in mind, even using a threshold of “one time GDP per capita”, corresponding to US$8827 for China, US$24,318 for Taiwan, US$59,532 for US, US$39,720 for UK, and US$9821 for BrazilCitation48, the estimated incremental cost per STP for branded vortioxetine versus generic venlafaxine XR are well below this threshold. In fact, even for a 6-month treatment scenario, the incremental cost of US$6793 per STP Mood and Tolerability was still below this threshold.

Although an acceptability threshold or willingness-to-pay for an additional successfully treated patient as defined in this study is not well defined, the cost-effectiveness estimates of this study may be put into perspective by quantifying the economic burden of depression. For example, the direct costs of hospitalization due to mental health disorders (depression, mania and childhood autism) averaged approximately US$3000 per admission in China in 2015Citation49. In their evaluation of the overall economic burden of MDD using 2010 US claims data and propensity-score matching, Greenberg and co-authors further estimated that the mean medical service costs (excluding prescription drug costs) were US$7604 for patients with MDD versus US$3465 for matched non-MDD patients, while the mean indirect costs of missed work were US$4084 and US$1353 per patient in the respective patient groupsCitation50. In this context, the estimated prices for vortioxetine versus venlafaxine XR across regions were overall acceptable, considering the pervasive negative impact of depression on patient functioning, and hence the potential cost savings related to better treatment outcomes, including improved work performance, increased treatment adherence and lower risk of relapse.

Limitations

The economic model applied in this study was simplified and not directly comparable to standard economic models based on QALYs or DALYs; as a consequence, using the threshold of “one time GDP per capita” is based on an assumption. Also, the model did not account for direct or indirect health-care costs other than drug costs; consequently, since the derived costs of MDD would be expected to be lower with vortioxetine versus venlafaxine XR owing to the clinical benefits associated with lower health-care costs and productivity lossCitation40,Citation51,Citation52, the cost-effectiveness analysis is therefore likely conservative from a vortioxetine perspective. Further, tolerability in this study was assessed by adverse events spontaneously reported by the patients which may be considered a less reliable measure than systematic assessments using a dedicated checklist or questionnaire, and likely to underestimate incidences. However, as underreporting would expectedly be comparable in the treatment groups, this would not likely bias the comparative analyses. It should also be noted that analyses used LOCF to impute missing observations which may bias the estimates if the underlying assumption is unjustified. However, because the impact in this head-to-head study would be the same for both treatment groups, the potential bias for the estimated treatment difference is likely negligible. Finally, the analysis was limited to the 8-week study duration and did not assess long-term treatment outcomes; moreover, the extrapolation for a 6-month treatment period was assumed, yet the evolution of treatment differences, and hence the incremental costs per STP over time, is not known.

Conclusions

This study showed higher rates of treatment success beyond mood symptoms with vortioxetine versus venlafaxine XR among Asian patients with MDD, with a statistically significant treatment difference for symptomatic improvement without compromised tolerability. Although vortioxetine was not dominant in the base case for the cost-effectiveness analysis, vortioxetine consistently dominated versus branded venlafaxine XR across region sensitivity analyses. These results support the benefits reported in previous studies with vortioxetine relative to other antidepressants in terms of broad efficacy, tolerability and cost-effectiveness.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The SOLUTION study was supported by H. Lundbeck A/S.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

GW has disclosed that she has received honoraria for being an advisor to or providing educational talks for Lundbeck, Pfizer, Sumitomo, Janssen and Janssen, and Eli Lilly Company. K.Z. has disclosed that he has received honoraria from Lundbeck, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca, and Gilead. C.R.M., H.L., H.R., H.L.F.E. and A.E. have disclosed that they are full-time employees of H. Lundbeck A/S. CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

G.W., K.Z., C.R.M., H.L., H.R. and A.E. were involved in the conception and design of this work. H.L. and H.L.F.E. performed the data analyses, and C.R.M., H.L., H.R., H.L.F.E. and A.E. were involved in the interpretation of the data. H.L.F.E. developed the first draft of the manuscript; all authors revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content and all authors have approved of the final version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (5.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully wish to thank all participants of the study, as well as the investigators and sites involved in conducting the SOLUTION study. No assistance in the preparation of this article is to be declared.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. The authors may be contacted for further data sharing.

Notes

Notes

i Brintellix, H. Lundbeck A/S, Valby, Denmark.

ii Effexor, Pfizer Inc., NY, USA.

References

- World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

- World Health Organization. WHO China Office Fact sheet. Beijing, China: World Health Organization; 2017.

- Hsieh CR, Qin X. Depression hurts, depression costs: the medical spending attributable to depression and depressive symptoms in China. Health Econ. 2018;27(3):525–544.

- Zhang M. Major depressive disorder treatment guidelines in China. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(Suppl E1):e06.

- Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, et al. Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder. Remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(9):851–855.

- Kelly K, Posternak M, Alpert JE. Toward achieving optimal response: understanding and managing antidepressant side effects. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10(4):409–418.

- Kikuchi T, Suzuki T, Uchida H, et al. Association between antidepressant side effects and functional impairment in patients with major depressive disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(1):127–133.

- Demyttenaere K. Risk factors and predictors of compliance in depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13:69–75.

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1357–1366.

- Citrome L. Vortioxetine for major depressive disorder: an indirect comparison with duloxetine, escitalopram, levomilnacipran, sertraline, venlafaxine, and vilazodone, using number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. J Affect Disord. 2016;196:225–233.

- Zimovetz EA, Wolowacz SE, Classi PM, et al. Methodologies used in cost-effectiveness models for evaluating treatments in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2012;10(1):1–1.

- Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB, Posternak MA, et al. Remission in depressed outpatients: more than just symptom resolution? J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(10):797–801.

- IsHak WW, Bonifay W, Collison K, et al. The recovery index: a novel approach to measuring recovery and predicting remission in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:369–374.

- IsHak WW, Greenberg JM, Cohen RM. Predicting relapse in major depressive disorder using patient-reported outcomes of depressive symptom severity, functioning, and quality of life in the individual burden of illness index for depression (IBI-D). J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):59–65.

- Solomon DA, Leon AC, Endicott J, et al. Psychosocial impairment and recurrence of major depression. Compr Psychiatry. 2004;45(6):423–430.

- Lam RW, McIntosh D, Wang J, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 1. Disease burden and principles of care. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):510–523.

- Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB, Posternak MA, et al. How should remission from depression be defined? The depressed patient’s perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):148–150.

- Demyttenaere K, Donneau A-F, Albert A, et al. What is important in being cured from depression? Discordance between physicians and patients (1). J Affect Dis. 2015;174:390–396.

- Thase ME, Mahableshwarkar AR, Dragheim M, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials of vortioxetine for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26(6):979–993.

- Baldwin DS, Chrones L, Florea I, et al. The safety and tolerability of vortioxetine: analysis of data from randomized placebo-controlled trials and open-label extension studies. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(3):242–252.

- Katona C, Hansen T, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced, fixed-dose study comparing the efficacy and safety of Lu AA21004 in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(4):215–223.

- Thase ME, Efficacy and tolerability of once-daily venlafaxine extended release (XR) in outpatients with major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(9):393–398.

- Thase ME, Entsuah AR, Rudolph RL. Remission rates during treatment with venlafaxine or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178(3):234–241.

- Wang G, Gislum M, Filippov G, et al. Comparison of vortioxetine versus venlafaxine XR in adults in Asia with major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(4):785–794.

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134(4):382–389.

- Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(Supplement 3):89–95.

- Llorca P-M, Lançon C, Brignone M, et al. Relative efficacy and tolerability of vortioxetine versus selected antidepressants by indirect comparisons of similar clinical studies. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(12):2589–2606.

- Thase ME, Danchenko N, Brignone M, et al. Comparative evaluation of vortioxetine as a switch therapy in patients with major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27(8):773–781.

- Florea I, Loft H, Danchenko N, et al. The effect of vortioxetine on overall patient functioning in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. 2017;7(3):e00622.

- McIntyre RS, Harrison J, Loft H, et al. The effects of vortioxetine on cognitive function in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of three randomized controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;19(10):pyw055.

- Baune BT, Brignone M, Larsen KG. A network meta-analysis comparing effects of various antidepressant classes on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) as a measure of cognitive dysfunction in patients with major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;21(2):97–107.

- Woo YS, Rosenblat JD, Kakar R, et al. Cognitive deficits as a mediator of poor occupational function in remitted major depressive disorder patients. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2016;14(1):1–16.

- Lam RW, Kennedy SH, McIntyre RS, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder: effects on psychosocial functioning and implications for treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(12):649–654.

- Langer J, Hunt B, Valentine WJ. Evaluating the short-term cost-effectiveness of liraglutide versus sitagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes failing metformin monotherapy in the United States. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(3):237–246.

- Christensen MC, Loft H, McIntyre RS. Vortioxetine improves symptomatic and functional outcomes in major depressive disorder: a novel dual outcome measure in depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2018;227:787–794.

- Cohen RM, Greenberg JM, IsHak WW. Incorporating multidimensional patient-reported outcomes of symptom severity, functioning, and quality of life in the individual burden of illness index for depression to measure treatment impact and recovery in MDD. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):343–350.

- Hawley CJ, Gale TM, Sivakumaran T. Defining remission by cut off score on the MADRS: selecting the optimal value. J Affect Disord. 2002;72(2):177–184.

- Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Spann ME, et al. Assessing remission in major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder clinical trials with the discan metric of the Sheehan disability scale. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(2):75–83.

- Jha MK, Minhajuddin A, Greer TL, et al. Early improvement in work productivity predicts future clinical course in depressed outpatients: findings from the CO-MED trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(12):1196–1204.

- Mauskopf JA, Simon GE, Kalsekar A, et al. Nonresponse, partial response, and failure to achieve remission: humanistic and cost burden in major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(1):83–97.

- Sheehan DV, Nakagome K, Asami Y, et al. Restoring function in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;215:299–313.

- Choi SE, Brignone M, Cho SJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of vortioxetine versus venlafaxine (extended release) in the treatment of major depressive disorder in South Korea. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16(5):629–638.

- Christensen MC, Munro V. Cost per successfully treated patient for vortioxetine versus duloxetine in adults with major depressive disorder: an analysis of the complete symptoms of depression and functional outcome. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(4):593–600.

- Soini E, Hallinen T, Brignone M, et al. Cost–utility analysis of vortioxetine versus agomelatine, bupropion SR, sertraline and venlafaxine XR after treatment switch in major depressive disorder in Finland. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;17(3):293–302.

- Eichler HG, Kong SX, Gerth WC, et al. Use of cost-effectiveness analysis in health-care resource allocation decision-making: how are cost-effectiveness thresholds expected to emerge? Value Health. 2004;7(5):518–528.

- McCabe C, Claxton K, Culyer AJ. The NICE cost-effectiveness threshold: what it is and what that means. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(9):733–744.

- WHO Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Macroeconomics and health: investing in health for economic development. Report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

- World Bank. 2017 [cited 2019 Apr 17]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ny.gdp.pcap.cd

- Chen W, Wang S, Wang Q, et al. Direct medical costs of hospitalisations for mental disorders in Shanghai, China: a time series study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e015652.

- Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(02):155–162.

- Knoth RL, Bolge SC, Kim E, et al. Effect of inadequate response to treatment in patients with depression. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(8):e188–e196.

- Birnbaum HG, Kessler RC, Kelley D, et al. Employer burden of mild, moderate, and severe major depressive disorder: mental health services utilization and costs, and work performance. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(1):78–89.