Abstract

Background: Current healthcare professional consensus-generating methodologies work by forcing consensus, which risks corrupting original opinions and often fails to assess prior expert knowledge awareness. Experience gained with a novel method in a progressive life-long rare disease, X-linked hypophosphataemia, which addresses these risks is presented here.

Methods: Four case-studies are reported, presenting a novel methodology comprised of two survey rounds. Round 1 generated a list of items from healthcare professionals in response to an open-ended research question, alongside systematic literature reviews (when appropriate). These responses were thematically coded into mutually exclusive items then used to develop a structured questionnaire (Round 2), for which each participant identified their level of agreement using Likert scales; all responses were analyzed anonymously. Item awareness, observed agreement, consensus and prompted agreement were objectively measured.

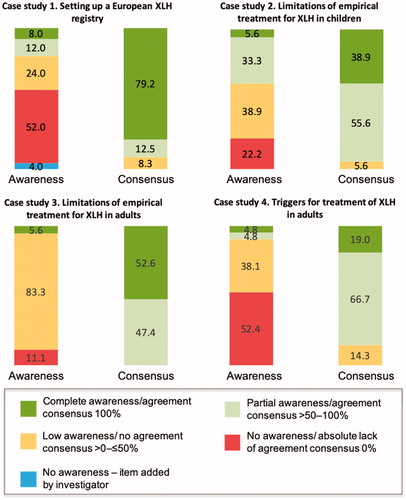

Results: The free-text responses to Round 1 tested the awareness of specific items regarding establishing a European registry for X-linked Hypophosphatemia (XLH), limitations of empirical treatment for XLH (adults and paediatrics), and triggers for treatment of XLH in adults. The four cases showed different levels of item awareness, observed consensus and degrees of prompted agreement. All participants agreed or strongly agreed with statements based on the most frequent items listed in Round 1. Less frequent Round 1 items had various degrees of prompted agreement consensus; some did not reach the consensus threshold of >50% participant agreement.

Conclusions: Observed proportional group awareness and consensus is quicker than the Delphi technique and its variants, providing objective assessments of expert knowledge and standardized categorization of items regarding awareness, consensus and prompting. Further, it offers tailored management of each item in terms of educational need and further investigation.

Introduction

In healthcare, consensus aligns opinion of experts and enables decisions to be made about a specific need or question, particularly when published evidence is either too extensive, confusing, or contradictory, or there is a dearth of evidence. Despite being the lowest quality of evidence, expert opinion consensuses often bridge the gap between no evidence and “some” evidence, consisting of anecdotal or case study reports subject to bias interpretation.

Methodologies or procedures used to gain consensus among healthcare professionals include the Delphi technique, modified Delphi techniques, and the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. The original Delphi technique, developed in the 1950s by the RAND Corporation to make predictions or for forecasting future events, has been refined and modified for use in many different areas, including government and healthcareCitation1. The core components of the Delphi technique, including many of its variations, comprise anonymity, iteration with controlled feedback, statistical group response, and expert inputCitation2. Where the Delphi technique and modified Delphi techniques differ is that the original Delphi technique starts with an open-ended questionnaire that is given to a panel of selected experts to solicit specific information about a subject or content areaCitation1. In contrast, a modified Delphi technique begins with a list of carefully pre-selected items, often using a systematic literature review as a starting pointCitation3. In this way, a modified Delphi consensus is based upon previously published evidence, the robustness of which can be readily assessed and categorized. The RAND/UCLA appropriate method was developed to combine the best available scientific evidence with the collective judgment of experts to yield a statement regarding the appropriateness of performing a procedure at the level of patient-specific symptoms, medical history, and test results; thus the resulting consensus is specific to one disease of an explicit severityCitation4.

There are several potential problems with the current procedures of consensus building in a healthcare setting, the first being that these methods all force a consensus and, as such, the original opinion may be corrupted through the consensus-generating process; often there is no way of knowing how closely the final consensus represents the original opinion of experts. Secondly, these methods do not measure or indicate awareness of items at the beginning of the process. Information or knowledge is required on which to base a consensus; a person cannot hold an opinion on something that they have no knowledge of. Furthermore, the selection of the expert panel may influence the final consensus, particularly as experts are usually invited to participate based on an assumption of knowledge prior to starting the consensus process. This assumption is typically based on the experts’ published research and/or current research interests. As such, an assessment of knowledge awareness prior to the consensus process would inform the reliability of the final consensus, yet this is rarely included as part of consensus reporting in a healthcare setting. Lastly, these consensus processes do not indicate prompting of item awareness, for example, the interaction between expert consensus and subject matter prompting.

Any process to obtain consensus from a group of experts would benefit from understanding awareness of items on which a later consensus is to be formed. The four case studies about X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH) are reported to demonstrate the principle of group “awareness” of items and its relationship with consensus on items retention. XLH is a rare, hereditary and progressive disorder affecting around 1 in 20–25,000 individuals and is characterised by phosphate wasting mediated through elevated levels of circulating fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 23, resulting from mutations in the phosphate regulating endopeptidase homolog, X-linked (PHEX) geneCitation5–8. Paediatric patients with XLH typically present with complications such as impaired and disproportional growth, progressive bowing of load bearing limbs and rickets, before developing issues such as osteomalacia, hearing deficits, musculoskeletal dysfunction and dental complications as adultsCitation9,Citation10.

Here, the novel methodology is described and the concept of proportional group knowledge awareness, prompted and observed consensus of items arising from list-generating questioning are further explored using these case studies.

Methods

The methodology employed within the case studies described below was developed by the author prior to case study conception.

Case studies

Four case studies designed by the author were used to define and confirm the methodology for assessing proportional group awareness and consensus of items arising from list-generating questioning. These case studies were chosen as they represented a range of questions and scenarios to fully explore the novel methodology ().

Table 1. Summary of case studies.

Participants

Participants, or experts, for each case study were recruited according to pre-specified criteria to confirm their experience in the area of interest relating to the research question (). For case study 1, recruitment was based on participants having a similar level of knowledge regarding an XLH registry, and exposure to the same project information prior to participation. Participants for case study 1 were recruited from the Medialis Real World Evidence Asset Management Division team of clinical study managers. The participants for case studies 2, 3 and 4 were recruited from a cohort of practicing doctors who treat patients with XLH in Europe; these participants were identified via publication history, clinical trial involvement, guideline writing committees and/or peer recommendation. Potential participants identified as above were contacted via email and/or phone and were recruited between October 2016 and March 2018. For each participant, relevant experience with regards to the inclusion criteria was recorded.

Study procedure and design

Item-generation questionnaire (round 1)

Surveys were constructed and distributed electronically via email using SurveyMonkeyCitation11. During Round 1, the item-generation round, participants were asked to complete an open-ended question, using up to 10 blank fields for their answers. For example, in case study 1, participants were asked to identify specific points which they would recommend other teams focusing on when running a registry for patients with rare diseases by answering a single open ended question: “With specific reference to your experience in setting up and implementing the XLH Registry, what recommendations would you make to other groups wishing to implement a similar European rare-disease registry?” The survey allowed for free text responses, and participants submitted their recommendations or responses using terms and phrases of their choosing. Each participant was given six hours to complete the exercise and asked to submit up to 10 recommendations. For the other case studies, participants were allocated a pre-agreed amount of time to complete Round 1. The timings were dictated by the urgency of the need for the results and the availability of the participants; case study 1 was “business critical” and therefore required a short turn-around, whilst case studies 2–4 included extremely busy clinicians and so time-frames were adjusted accordingly.

For each case study, responses to the item-generation round were collated into themes and developed into mutually exclusive items by the investigator. Responses to Round 1 were analyzed using a process of content analysis and open coding to categorize items into themes. This process was based upon internal modifications of thematic analysis principles and was conducted independently by the author and one other researcher trained in the methodologyCitation12,Citation13.

Item generating using literature reviews

Where appropriate, literature reviews were used to supplement item generation by the participants. Specific terms were used to search an online database (MEDLINE via PubMed; ). The search results were manually reviewed, and the abstracts of relevant articles were coded using the same technique as the participant responses to the list-generation question. Items generated from the literature review that were not identified by the participant responses to the Round 1 question were included in Round 2; the frequency of each item generated from the literature review was not recorded.

Structured questionnaire to observe consensus (round 2)

The compiled list of items/themes were reviewed and refined by the investigator and included in Round 2 as structured questionnaires (Supplementary Materials). The investigator had the opportunity to add items/themes not originally included as part of the response to Round 1 in order to test prompted agreement. Similarly, items from a systematic literature review could be added if not identified by the participants in their responses to the Round 1 question. Participants who completed Round 1 were asked to complete the Round 2 questionnaire; this survey was also compiled using SurveyMonkey and an access link was circulated via email. Each participant was asked to state his or her level of agreement with each statement on a five-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neither agree or disagree, disagree or strongly disagree). Responses to the structured questionnaire in Round 2 were used to determine observed consensus, proportional group awareness and the effect of prompting.

Analysis plan

Participants were asked to include their names in the surveys to ensure that all participants completed the relevant surveys. Responses to surveys were anonymized before analysis.

Four case studies were considered sufficient to test the methodology. Consensus was defined as agreement of more than half of the participants, i.e. a simple majority. Data from the item-generation round and the consensus round were exported from SurveyMonkey to a Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheet for analysis.

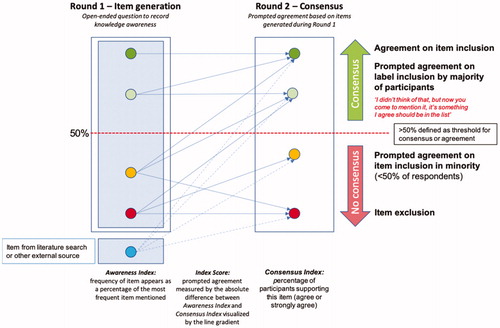

Awareness Index

The responses to the Round 1 questionnaire were used to assess knowledge awareness by calculating the frequency of each coded item in relation to the overall most frequently occurring coded item (the Awareness Index); a minimal awareness threshold was defined as an Awareness Index >50%. If items generated from a literature review were not mentioned by the participants’ responses in Round 1, then there was no awareness of the item by the participants ().

Figure 1. Overview of awareness and agreement consensus. The awareness and agreement consensus overview is categorized according to the Awareness Index (frequency of each coded item in relation to the overall most frequently occurring coded item in Round 1) and the Consensus Index (calculated using the percentage of participant agreement with each statement during the structured questionnaire in Round 2). Complete awareness of an item has an Awareness Index of 100% and complete agreement consensus has a Consensus Index of 100%. Partial awareness and consensus have indices >50–100%. Low awareness and no agreement consensus have indices 0–≤50%. XLH, X-linked hypophosphatemia.

Consensus Index

The Consensus Index was calculated as the percentage of participants who agreed or strongly agreed with each statement ().

Index score to measure prompting

The Index Score was used to measure prompting during Round 2. The concept of prompting was pre-specified to have occurred if the absolute difference between the Awareness Index (calculated using the item-generation responses in Round 1) and the Consensus Index (calculated using the percentage of participant agreement with each statement during the structured questionnaire in Round 2) was ≥0.05 (or 5%); a determination of no prompting was made if the absolute difference was <0.05 (or 5%). Unprompted consensus was defined when a majority of participants suggested an item during Round 1, and a majority of participants subsequently agreed or strongly agreed that the item was important in Round 2. Any item that was not suggested by the participants during Round 1, but which was agreed to be important in Round 2, was said to be completely prompted.

Results

The case studies were conducted between March 2017 and December 2019. The number of participants ranged between 3 and 10 for each case study. A description of the participants for each case study is summarized in .

Table 2. Case study participants.

In case study 1, 10 blank fields were used by the participants in Round 1; in all other case studies up to six blank fields were completed. Case study 1 was completed in 6 h, whilst case studies 2–4 were all completed within a period of 3 weeks.

Systematic literature review

Concurrent literature reviews were conducted in MEDLINE via PubMed in February 2018 for case studies 2 and 3. In total, 466 papers were identified, of which 72 passed all inclusion and exclusion criteria and were included in the study analysis. No additional items were generated for these case studies from the literature reviews when compared with the Round 1 survey results. The research question posed in case study 1 was too narrow and specific to be answered using currently published literature, so no literature review was performed in this case.

Responses to item-generation (round 1) and structured (round 2) questionnaires

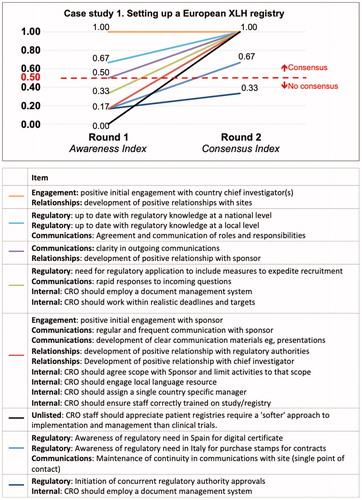

In Round 1 of case study 1 (recommendations for setting up a European XLH registry), five key areas were identified by the participants: engagement, regulatory, communications, relationships and internal procedures. The most frequently mentioned coded items were “positive initial investigator engagement” and “positive relationship with sites”; each of these items was mentioned twice by each participant in their free-text responses. The least frequently mentioned coded items were mentioned once each ().

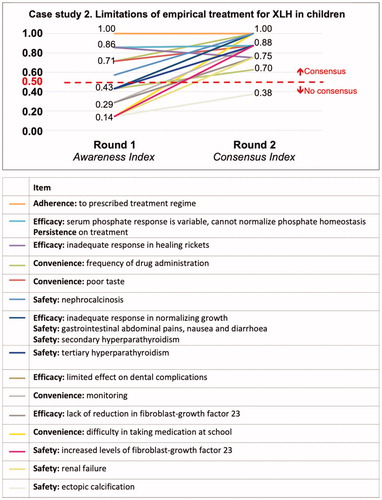

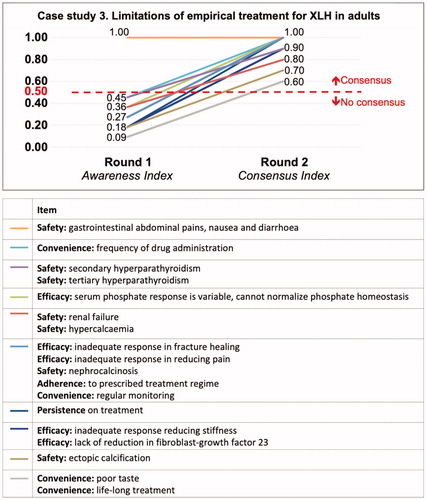

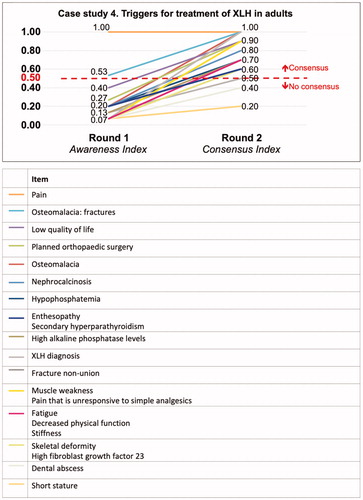

In case studies 2 and 3 (limitations of treatment for XLH in either children or adults), although there were differences in the frequency of each item in each area depending whether treatment referred to children or adults, the participants also identified five key areas in response to the Round 1 question: persistence of treatment, convenience, adherence, efficacy and safety ( and ). Case study 4 looked at triggers for treating XLH, which showed a spread of both item awareness and of consensus for each statement ().

Awareness (item generation) and prompted agreement (consensus)

When presented with the structured questionnaire in Round 2, many of the participants agreed or strongly agreed that the items generated during Round 1 were important with a majority of items having some degree of prompted agreement consensus. Participants were prompted to consider most items, as can be seen from the gradients of each line visualizing the absolute difference (Index Score) between the Awareness Index and the Consensus Index in . The Index Score for each item was also numerically calculated (data not shown).

Discussion

This series of case studies have shown how to methodically observe proportional group awareness and subsequent consensus of items arising from list-generating questioning. The free-text responses to the item-generation round tested the awareness of specific concepts or items regarding setting up a European XLH registry, the limitations of empirical treatment for XLH in children and adults, and triggers for treatment of XLH in adults. The purpose of this methodology is not to force a consensus, but to evaluate the current knowledge and opinions of the selected experts. It is unique in its objectiveness, its approach and interpretation compared with traditional consensus generating methodologies.

This method of observing proportional group awareness and consensus consists of two rounds of questionnaires. The first survey consists of an open-ended question for the experts to answer. Answers can be used to generate an item list and assess the awareness of the experts of a particular subject; it also allows the awareness of items to be recorded in an unprompted way. The structured questionnaire generated from the items identified during the first round can also have items added to it by the investigator(s). As such, the process of observing proportional group awareness and consensus is flexible, allowing the input of results from literature searches into the structured questionnaire in Round 2, thus providing the participants the benefit of reviewing items that may not have been suggested in their first round.

The selected case studies have also demonstrated that the minimum allowable number of participants for successful method implementation is three – two opposing positions and a final casting vote. Further, the potential for an unlimited number of coded in the Round 2 questionnaire – driven heavily by the improvements in time taken to complete the Likert-scales in Round 2, compared to traditional Delphi approaches – ensures that all expert opinions are equally evaluated and that a holistic understanding of the research question at hand is developed.

In case study 1, setting up a European XLH registry, recommendations and learns were elicited from a small number of experts with specific reference to a single project; the key aim of this case study was to inform best practices. The unprompted consensus items of a positive initial engagement with a country chief investigator and developing positive relationships with sites show that these are at the forethought of clinical study managers minds when designing and setting up a successful registry. Nevertheless, participants had minimal awareness of the majority of items identified during Round 1. The high number of items that were elicited with the minimum observed frequency may be driven by the low number of advisors (n = 3) and variation in individual opinion. Nevertheless, this case study demonstrated the ability to utilize a minimum of three advising participants, as well as capturing their response to the “test” item that was introduced.

The case studies for empirical treatment of XLH in both children and adults demonstrated the different levels of knowledge or awareness of treatment options. For treating children, the highest level of awareness of items generated indicated that the panel of experts focused on the same items, including adherence to treatment, problems of variable serum phosphate levels and inadequate response to healing rickets. The participants’ responses enabled a small number of clear items generated for empirical treatment of XLH in children. This may be due to good alignment in the level of experience of the experts or may indicate that the question is well defined, enabling a small number of items to be generated. This case also highlights the benefit of observing initial item awareness; items found to have an Awareness Index <50% may benefit from efforts to increase awareness through education, for example. In contrast, the same question asked about the treatment of adults demonstrated a low level of awareness of items identified by the expert participants. This may represent the diffuse knowledge of the subject, or genuinely disparate positions on the items to be included; in this particular case this appears representative of the current clinical pictureCitation9,Citation10. However, the participants did show a high level of agreement consensus during Round 2 in both cases 2 and 3.

In case study 4, awareness of triggers for treatment of XLH in adults was low except for pain, which had unprompted consensus as being an important trigger for treatment. A wide variation in opinion through divergent local practices or low familiarity with the subject matter may be responsible for the low awareness of other items generated. Again, in this particular case, the results mirror the current clinical landscape for adults with XLH and their cliniciansCitation9,Citation10.

In the case studies reported here, the first had participants with specific knowledge and experience setting up an XLH registry, whereas the other case studies all had participants who were experts in treating patients with XLH and had strong publishing records regarding XLH in peer-reviewed journals. For the purposes of this methodology, the level of expertise required depends upon the question being asked. As such, experts could be defined in a clinical setting by the number of patients they treat per year with a specific disease, the number of patients enrolled in a clinical trial, or other discerning attribute that makes the person an expert in their field and able to provide valuable insights to the question at hand.

In order to have an opinion from which to form a consensus, a group of experts must first be aware of the key aspects of the subject of interest – without one there cannot be the other. Whilst a threshold level of awareness of their subject matter would, by definition, qualify an individual as an expert, no-one can be omniscient and so it follows that being made aware of new material would inevitably require them to form an opinion on it that may influence the overall consensus. As such, there is necessarily internal (within the expert group) and external (sources outside the expert group) prompting when it comes to forming an opinion.

The expert responses to the structured questionnaire allow the investigator(s) to observe any consensus that arises, and determine whether it is prompted or unprompted. In these case studies, prompted agreement was pre-specified as a difference of 5% or more in the Index Score (the absolute difference between the Awareness Index and the Consensus Index for an item); traditionally, 5% has been considered a threshold for statistical significance. It was recognized that the prompting may be “coarse” given the small number of participants, particularly in case study 1; however, the observation of prompting could still be made on data collected during Round 1 and Round 2. The advantage of maintaining anonymity of the participating experts, both in terms of their responses and identities within the survey, is also evidenced here, as it mitigates the effect of dominant individuals, manipulation or compulsion to confer to certain viewpointsCitation14,Citation15. Moreover, anonymity preserves the independence in item generation during Round 1. It is also important to highlight that whilst some items may have significantly more support after prompting in Round 2, they may still fail to secure majority agreement, and therefore consensus, by the participants.

In these case studies, the lack of face-to-face meetings denied the opportunity to discuss pertinent topics, which may have been seen as a limitation; however, there is no reason why the process could not include a face-to-face discussion meeting, for example held after Round 1 and before the experts complete the Round 2 questionnaire.

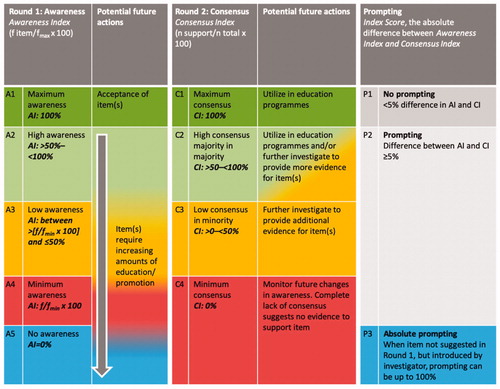

The ability to categorize items based on the difference between the Awareness Index and Consensus Index enables appropriate handling of these items (). For example, an item with both an Awareness Index and Consensus Index of 100% denotes complete awareness of an item with no prompting and which resulted in complete consensus; such an item can be considered well understood or common knowledge and, therefore, beyond challenge. For items with an Awareness Index < 50%, the degree of prompting observed in the performance of these items in Round 2 indicates how these items are appreciated when all experts are made equally aware of the item (as seen by the gradient of the slope between Round 1 and Round 2, or the Index Score). The performance of these items around the simple majority threshold of >50% provides insight into the “tipping” point of broad agreement. Items which are categorized as having a Consensus Index < 50% indicates a degree of education may be required in order to increase awareness of an accepted item (). Items gleaned from literature reviews or test suggestions which are introduced into Round 2 and subsequently prompted to <50% may indicate either a lack of threshold knowledge or awareness of the subject matter, or indeed a fundamental “challenge” to the norm; the latter may indicate an opportunity to redefine these norms. The consensus list can allow items to be utilized in further discussions without further investigation or used with a parallel investigation, or alternatively not used without formal investigation. Finally, in situations where there is no consensus in Round 2, the research team may simply opt to monitor these items and defer decision on active management until more is known about them.

Figure 6. Insights into stratifying knowledge awareness and prompted agreement. Interpreting differences between group awareness and consensus of items. Round 1 – Item Generation: Green circles represent group awareness of items identified during a list-generating question; orange circle represents items are possibly require more education about or represent a time-lag between expert awareness and the knowledge spreading to the wider academic community; red represents items that are possibly not as relevant to the study question; blue represents external source of item, for example, an item from a systematic literature review. Round 2 – Consensus: Green circles represent agreement or prompted agreement; orange circle represent prompted agreement but in the minority of participants, possibly because more research is required to provide more evidence; red circle represents agreement that item should be excluded. Arrows between Round 1 and Round 2 represent the level of prompted agreement with the steeper the slope the greater the level of prompted change of opinion. The Index Score represents the amount of prompted agreement between awareness (item-generating) and observed consensus.

Figure 7. Planning future actions based on awareness and consensus categories. Group awareness of items and prompted agreement consensus can be used to plan future actions according to pre-defined categories. Abbreviations. AI, Awareness Index; f, frequency of item reported by participants in their responses to Round 1 question; fmax, the number of times the most frequently mentioned item was mentioned in the responses to the Round 1 question; fmin, the number of times the least frequently mention item was mentioned in the response to the Round 1 question; CI, Consensus Index.

Observed proportional group awareness and consensus is typically a quicker process than the Delphi technique and its variants, which can be long and drawn out depending on the pre-specified level of agreement required. The Delphi technique often shows a change in participants’ views towards consensus and stability with each subsequent round, as indicated by an increase in percentage agreements, convergence of importance rankings, an increase in Kappa values and a decrease in comments as rounds progressedCitation16.

A potential limitation of the case studies reported here is that the Round 2 questionnaires were constructed in a way that encouraged agreement rather than disagreement, possibly leading to response biases; acquiescence bias, in particular. To mitigate this and test for acquiescence bias, in future studies Round 2 surveys could have a selection of questions that repeat the same concept or item but are reworded so that if the participant strongly agreed with the first statement, then they would be likely to strongly disagree with the repeated statement. For example, “Pain reported by the patient is the most important deciding factor with regards to treatment” and “Pain reported by the patient does not affect the type of treatment given”. However, there is currently some uncertainty about the level and impact of acquiescence bias, with some studies suggesting that strong acquiescence bias is only observed in very small proportions of participantsCitation17, whilst the applicability of reversed items to Likert rating scales is also questionable, with some studies suggesting that it may both negatively impact the precision and increase the variance of the conducted surveyCitation18.

Furthermore, specifically to this methodology, it may not be appropriate to negatively phrase statements in this way as the process is directed towards agreement consensus. The responses to the open-ended question in Round 1 are coded and lead to the statements listed in Round 2 and, as such, the participants who have suggested specific items in Round 1 are likely to agree with statements based on these items. In addition, the open-ended question asked in Round 1 needs to be carefully considered to ensure that with the objectives of the study will be able to be fulfilled.

The process of observing proportional group awareness and consensus takes account of knowledge awareness of the experts at the beginning of the consensus process, unlike the Delphi technique, modified Delphi and RAND/UCLA. Furthermore, there was no forced consensus, no attrition of participants, questionnaires were not sent to a wider group of experts who may not have the same level of knowledge and the process has been made more transparent with this new methodology. Although the Delphi technique is useful for determining judgement convergence, this does not necessarily mean that the resulting consensus is accurateCitation19. If participants fail to answer a question, or questions, in any particular round in Delphi, the results of that round may show a misleading bias towards agreementCitation16. Participants in the case studies reported here had similar levels of knowledge, so it was expected that they would have similar levels of prompted agreement for each item. Participants from different specialties would be more likely to have different levels of prompted agreement for each item identified during the list-generating round. Although the number of participants was relatively small in each case study, other studies have shown that only a small number of experts is required when assessing consensusCitation20.

The method of observing proportional group awareness and consensus could be used to answer any list generating question, for example, in therapy areas where higher level evidence is lacking, making us reliant on expert opinion (level 5 evidence) or in broader, non-healthcare related areas. Observing proportional group awareness and consensus would also be useful when a specific subjective interpretation is required to answer the research question, when assessing differing levels of knowledge and awareness of key information in order to develop education programmes, when assessing the time delay between expert knowledge and wider community knowledge, and in therapy areas in which randomized controlled trials are considered unethical (for example, some areas of obstetrics or oncology) thus limiting the quality of evidence available. This methodology could also be used to assess the level of knowledge of different groups of advisors who answer the same Round 1 question, which could be useful when developing regional education programmes. Similarly, repeating the Round 1 or Round 2 surveys would measure how knowledge about specific subjects changes over time. The value of observing proportional group awareness and consensus is that it elucidates unmet educational need, knowledge gaps, and the time-lag between expert knowledge (unpublished) and when it leaches to the broader academic community. Thus, the clear benefit of the unprompted list generation and group consensus methodology is that it helps assess the current level of understanding and the temporal lag between research and expert knowledge in a specific therapy area or topic. The difference between the unprompted awareness and the prompted agreement consensus identifies items or areas either where more education is required (in the case of items not listed by the participants, or listed by very few of them in Round 1) or where more research is required (in the case of no observed agreement consensus for a statement in Round 2).

Conclusion

In summary, the methodology described here to observe proportional group awareness and consensus provides an objective assessment of expert knowledge which is applicable to research areas where opinions may be subjective or based on limited evidence. It is especially useful in research areas where other consensus techniques may not be appropriate to apply. Standardized categorization of items regarding awareness, consensus and prompting offer the opportunity to manage each item or concept in a more tailored manner in terms of education and further investigation.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The case studies were conducted alongside but independent to paid services Medialis, Ltd was contracted to perform by one of its clients and the case studies themselves remain wholly funded by Medialis Ltd. Medical writing and editorial support were funded by Medialis, Ltd.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

RJ is the founder of Medialis, Ltd. Medialis conducted the case studies observing proportional group awareness and consensus. All study managers (AD, JM and JT) who were experts for the case study 1, are employees of Medialis. All other participants who took part in case studies 2, 3 and 4 were paid for their time. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

RJ was completely responsible for the conception, design of the work, the acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data and has drafted the work and substantively revised it. RJ has also approved the submitted version and has agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

MED_11_Casestudy_4.pdf

Download PDF (551.7 KB)MED_11_Casestudy_3.pdf

Download PDF (429.2 KB)MED_11_Casestudy_2.pdf

Download PDF (226.6 KB)MED_11_Casestudy_1.pdf

Download PDF (146.1 KB)Acknowledgements

Celia J Parkyn, PhD and Alexander T Hardy, PhD provided medical writing and editorial support for manuscript preparation. CJP was funded by Medialis, Ltd, and ATH is currently employed by Medialis Ltd. Jack Lambshead and Saiful Islam, both previous employees of Medialis Ltd, worked with the data used in the early case studies.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Hsu C-C, Sandford B. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2019;12:1–8.

- Goodman CM. The Delphi technique: a critique. J Adv Nurs. 1987;12(6):729–734.

- Custer RL, Scarcella JA, Stewart BR. The modified Delphi technique - a rotational modification. J Career Tech Educ. 1999;15(2):1–10.

- Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, et al. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual; 2001 [Accessed 2020 Jan 17]. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1269.html.

- Santos F, Fuente R, Mejia N, et al. Hypophosphatemia and growth. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28(4):595–603.

- Endo I, Fukumoto S, Ozono K, et al. Nationwide survey of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23)-related hypophosphatemic diseases in Japan: prevalence, biochemical data and treatment. Endocr J. 2015;62(9):811–816.

- Rafaelsen S, Johansson S, Raeder H, et al. Hereditary hypophosphatemia in Norway: a retrospective population-based study of genotypes, phenotypes, and treatment complications. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174(2):125–136.

- Beck-Nielsen SS, Mughal Z, Haffner D, et al. FGF23 and its role in X-linked hypophosphatemia-related morbidity. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):58.

- Carpenter TO, Imel EA, Holm IA, et al. A clinician’s guide to X-linked hypophosphatemia. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(7):1381–1388.

- Haffner D, Emma F, Eastwood DM, et al. Clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of X-linked hypophosphataemia. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15(7):435–455.

- SurveyMonkey, Inc. SurveyMonkey: The world’s most popular free online survey tool. San Mateo (CA): SurveyMonkey, Inc.; 1999.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11(4):589–597.

- Kirkley A, Alvarez C, Griffin S. The development and evaluation of a disease-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for disorders of the rotator cuff: The Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index. Clin J Sport Med off J Can Acad Sport Med. 2003;13(2):84–92.

- Walker AM, Selfe J. The Delphi method: a useful tool for the allied health researcher. Int J Ther Rehabil. 1996;3(12):677–681.

- Holey EA, Feeley JL, Dixon J, et al. An exploration of the use of simple statistics to measure consensus and stability in Delphi studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):52.

- Hinz A, Michalski D, Schwarz R, et al. The acquiescence effect in responding to a questionnaire. GMS Psycho-Soc Med. 2007;4:1–9.

- Suárez-Álvarez J, Pedrosa I, Lozano LM. Using reversed items in Likert scales: a questionable practice. Psicothema. 2018;30(2):149–158.

- Cousien A, Obach D, Deuffic-Burban S, et al. Is expert opinion reliable when estimating transition probabilities? The case of HCV-related cirrhosis in Egypt. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):39.

- Akins RB, Tolson H, Cole BR. Stability of response characteristics of a Delphi panel: application of bootstrap data expansion. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5(1):37.