Abstract

Objectives

To help optimize triple therapy use, treatment patterns and disease burden were investigated in patients in Japan with persistent asthma who initiated multi-inhaler triple therapy (inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonist; ICS/LABA/LAMA).

Methods

This retrospective, observational cohort study using health insurance claims data included adults with persistent asthma who initiated triple therapy in 2016. Patients who were prescribed ICS/LABA in 2016 were included as an ICS/LABA-matched cohort. Patients were stratified into those with asthma only and those with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) codes (asthma-COPD overlap [ACO]). Patient data from 1-year prior to 1 year post index date were analyzed.

Results

For patients with asthma only in the triple therapy and ICS/LABA cohorts, baseline demographics were similar. A higher proportion of the triple-therapy cohort than the ICS/LABA cohort was receiving high-dose ICS at index (68.2% and 27.6%, respectively), and had experienced an exacerbation in the last year (64.0% and 29.4%, respectively). The proportion of patients with asthma only who developed any exacerbation was lower in the year following initiation of triple therapy compared with the year prior to initiation of triple therapy (45.8% vs 64.0%, respectively). For asthma only patients receiving triple therapy, the mean (standard deviation) proportion of days covered and medication possession ratio was 0.51 (0.36) and 0.86 (0.16), respectively. Similar trends were seen in patients with ACO in the triple-therapy and ICS/LABA cohorts.

Conclusion

Evidence from this study may serve as a reference for the use of inhaled triple therapy for asthma.

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease defined by symptoms such as wheeze, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough, together with variable expiratory airflow limitationCitation1. In 2015, asthma was the most common respiratory disease worldwide with a global prevalence of 358.2 millionCitation2. It is estimated that 1–18% of the global population are affected by asthmaCitation1, and in Japan, this figure is around 4%Citation3.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are commonly recommended for the treatment of asthma, with the concomitant use of other long-term management medications depending on severityCitation1. However, exact step-up guidelines differ slightly between regions. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2019 guidelines recommend a 5-step approach to asthma treatment: Step 1–as-needed low-dose ICS/formoterol; Step 2–daily low-dose ICS or as-needed low-dose ICS/formoterol; Step 3–low-dose ICS plus a long-acting β2-agonist (LABA); Step 4–medium-dose ICS-LABA, with add-on tiotropium bromide (tiotropium; a long-acting muscarinic antagonist [LAMA]) as another controller option; and Step 5–high-dose ICS-LABA plus an add-on therapy such as tiotropium depending on phenotypeCitation1. In Japan, as-needed low-dose ICS/formoterol is off-label and is not recommended by the Japanese Society of Allergology (JSA) guidelines. Otherwise, the JSA guidelines recommend a similar 4-step approach similar to that recommended by GINA: Step 1–low-dose ICS; Step 2–low- to medium-dose ICS plus an additional treatment if required (LABA, leukotriene receptor antagonist [LTRA], or theophylline); Step 3–medium- or high-dose ICS plus one or more additional treatments (including LAMA); Step 4–high-dose ICS plus two or more additional treatments (including biologics or oral corticosteroids [OCS]) as long-term management agents (basic treatment)Citation4. The 2018 JSA guidelines were updated to also include a LAMA as an additional treatment from Step 2 onwardsCitation5. ICS with the addition of LABA and/or LAMA as needed is also the recommended treatment for patients with persistent airflow limitation alongside several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPDCitation1,Citation4,Citation6, defined by the GINA guidelines as asthma-COPD overlap (ACO)Citation1.

ICS/LABA/LAMA (referred to here as triple therapy) is a potential Step 3 or Step 4 treatment option for moderate or severe persistent asthma, respectively. Triple therapy is not available as a single inhaler for asthma in Japan, meaning multiple devices must be used. The aim of this study was to describe the population of patients in Japan with persistent asthma who initiated multiple-inhaler triple therapy in 2016. Analyzing the characteristics of patients receiving triple therapy may help to optimize its use in the treatment of asthma.

Materials and methods

Study design

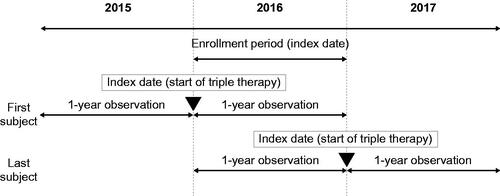

This retrospective, observational cohort study used medical and pharmacy claim data from the JMDC Claims Database (JMDC Inc., Minato-ku, Tokyo), which contains health insurance claims (medical [outpatient, inpatient] and pharmacy) and specific health check-up data provided by contract health insurance societies in Japan. As of December 2016, the JMDC database contained around 3.8 million people <75 years of age, including healthy individuals. Eligible patients who initiated triple therapy during 2016 (the enrollment period) were observed for a 2 year period (the observation period), which ran for 1 year prior to and 1 year after the start of triple therapy (the index date) ().

Ethics

This study complied with all applicable laws regarding subject privacy, Declaration of Helsinki, and Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects (partially amended on 28 February 2017). Prior to analysis start, the ethics committee of Kitamachi Clinic (Musashino-city, Tokyo) reviewed the protocol and approved this study on 17 July 2018.

Study population

Patients in the triple-therapy cohort were males and females ≥15 years of age on the index date with persistent asthma (≥4 asthma diagnoses in the year prior to the index date; asthma diagnosis by a physician is required for every prescription in Japan) who had initiated inhaled triple therapy (ICS/LABA combination and tiotropium) with two inhalers in 2016. The index date for the triple-therapy cohort was the triple therapy start date (i.e. the day on which both ICS/LABA combination and tiotropium were prescribed). In Japan, ICS/LABA combination is used more frequently than ICS alone or ICS plus LABA with two inhalers in patients with persistent asthma. Therefore, we considered triple therapy with three inhalers to be less common and included patients using two inhalers. Since tiotropium is the only LAMA approved for use in asthma, we included only tiotropium as LAMA for triple therapy. A reference cohort of patients ≥15 years of age with persistent asthma who had been prescribed an ICS/LABA combination (in a single inhaler) in the year prior to the index date was also included (ICS/LABA cohort). To be included in the ICS/LABA cohort, patients had to have received their ICS/LABA prescription in the same month as an index date prescription in the triple-therapy cohort. The index date for the ICS/LABA cohort was the date of ICS/LABA combination prescription. There could be multiple patients in the reference cohort with “matching” index date (i.e. in the same month) to the triple therapy cohort. To investigate differences in patient characteristics including age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, and comorbidities between triple therapy and ICS/LABA cohorts, we did not match these variables.

All eligible patients were enrolled in the JMDC Database from 1 year prior to and 1 year after the index date. Patients who were prescribed triple therapy in the 1 year prior to the index date (not including the index date itself) were excluded, and patients included in the triple-therapy cohort were excluded from the ICS/LABA cohort.

As age group, comorbidities, and treatment patterns are different between asthma and COPDCitation7, analyses were performed separately for patients with asthma only and those with ACO.

Outcomes

Data on the following variables were captured from the database: patient demographics at index (age, sex, BMI, current smoking status [BMI and current smoking status were collected in the year prior to the index date; if multiple data, the most recent was included for analysis]); comorbidities in the year prior to the index date (for diagnoses codes, see Supplementary Table S1); disease management in the year before and after the index date (for drug and other treatment codes, see Supplementary Table S2 and Table S3, respectively); disease burden in the year before index; and triple therapy persistence in the year after the index date.

Data were counted according to the presence or absence of COPD (including chronic bronchitis and emphysema). The presence or absence of COPD or other comorbidities was defined using the diagnosis in the claims. Comorbidities were regarded as “present” if they were diagnosed ≥2 times for COPD or other non-acute diseases (allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis, allergic conjunctivitis, allergic rhinitis, angina pectoris, angle-closure glaucoma, anxiety disorder, atopic dermatitis, atrial fibrillation, benign prostatic hyperplasia, chronic sinusitis, depression, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, food allergy, gastroesophageal reflux disease, hypertension, hyperuricemia/gout, lung cancer, myocardial infarction, nasal polyp, sleep disorder, valve disorder), or if they were diagnosed ≥1 time for acute diseases.

Disease management was characterized by the long-term asthma management medications (LTRAs, theophylline, biologics, other anti-allergics, transdermal LABA, oral LABA, long-term macrolides, and home oxygen therapy) prescribed in the 60 days prior to index, and the daily ICS dose at index. ICS doses considered to be low, medium and high use are shown in Supplementary Tables S4 and S5 where ICS daily dose (with fixed dose) could be specified. For long-term macrolides, those with 14- or 15-membered rings and a proportion of days covered (PDC) of ≥0.8 in the 60 days before the index were counted.

Disease burden was characterized by exacerbation and symptomatic asthma treatment (cough suppressants, expectorants, inhaled short-acting β2-agonist [SABA], injectable adrenaline, injectable corticosteroids, injectable SABA, injectable xanthines, OCS, oral SABA, oxygen inhalation, short-acting muscarinic antagonist [SAMA]) prescribed in the year prior to index, including the number of patients who experienced any exacerbation or an exacerbation requiring hospitalization. In the case of SABA use for which two inhalations per time of use was not standard, the number of inhalations was converted to the equivalent number for a two-inhalations-per-time SABA (Supplementary Table S6). As budesonide/formoterol is used for both long-term management and exacerbation treatment, budesonide/formoterol users were not counted in inhaled-SABA counts. OCS were calculated in terms of the amount equivalent to prednisolone (Supplementary Table S7). Disease burden was also captured for the year following index. Exacerbations that required a visit were counted when the following three conditions were satisfied: (1) asthma diagnosis (in the same month as condition 3); (2) prescription for respiratory preparations (ATC code: R03, R05, or R06) or systemic corticosteroids (on the same day as condition 3); (3) any of the following (a–d): (a) hospitalization; (b) late night, holiday, or emergency visit; (c) newly developing symptoms and prescription for asthma rescue medication (SABA inhalation solution by nebulizer or SAMA); (d) prescription for systemic corticosteroid (≤14 days) or xanthine injection. When condition 3c or 3d was satisfied, condition 2 was deemed to be satisfied. Fee codes for emergency visits are shown in Supplementary Table S8; the list of asthma exacerbation diagnoses is shown in Supplementary Table S9. Triple therapy persistence in the year after index was characterized by the proportion of patients adhering to triple therapy 3, 6, and 12 months after index date, the 1 year PDC, and medication possession ratio (MPR) during triple therapy. The allowable gap was 90 days.

Data analysis

A formal sample size calculation was not performed as this study was not hypothesis-based. Variables were analyzed descriptively and stratified by group/cohort. The data cut used for analysis was from January 2005 to August 2018. Quantitative variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Binary or categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. Since this study did not aimed to confirm effectiveness of triple therapy or its specific related factors, we did not perform any formal statistical analyses. Sample selection and creation of analytic variables were performed using the IHD platform (BHE, Boston, MA). Statistical analyses were undertaken with R, version 3.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Study population

Between January and December 2016, the database contained a total of 72,581 patients ≥15 years of age who had been diagnosed with asthma ≥4 times. Of these, 64,259 had asthma only and 8322 had ACO, of whom 326 and 579 patients, respectively, were triple therapy users (including those who initiated triple therapy in 2016 and continuous users from the previous year). For an overview of the 2015, 2016, and 2017 database populations, see Supplementary Table S10.

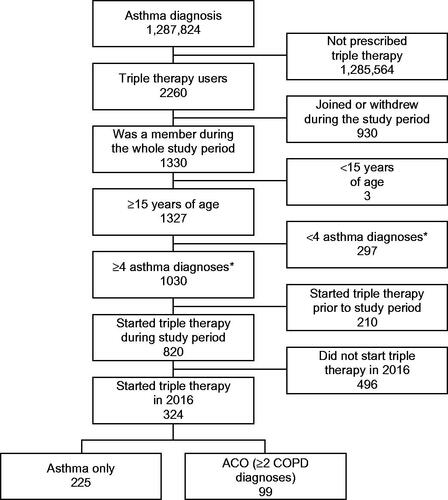

The cohort that initiated triple therapy in 2016 consisted of 324 patients who had received ≥4 asthma diagnoses in the 1 year before the index date. Of these, 225 had asthma only and 99 had ACO ().

Figure 2. Inclusion of the triple-therapy cohort. Abbreviations. ACO, asthma-COPD overlap; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. *In the year prior to the index date.

Additionally, 1321 patients with asthma only and 100 with ACO who were prescribed ICS/LABA combination in the same month of the index date in the triple-therapy cohort were included as an ICS/LABA-matched cohort to control the seasonal effect. The cohorts were not matched 1:1; there were >4 times more patients in the ICS/LABA cohort than the triple-therapy cohort.

For the asthma only group, 32.4% of index dates (starting triple therapy) fell during the autumn (September–November), making this the most frequent index season. The second most frequent index season was summer (June–August; 26.2%), followed by winter (December–February; 22.7%), and spring (March–May; 18.7%). A similar seasonal distribution was seen for the ACO group, but the differences between seasons were smaller; 27.3% in autumn, 25.3% each in summer and winter, and 22.2% in spring.

Baseline characteristics for the asthma-only and ACO groups, according to index date therapy type (ICS/LABA or triple therapy) are shown in . In general, baseline demographics were similar across therapy types within the asthma-only and ACO groups with the exception of the proportion of males in the ACO group, which was higher in the triple-therapy cohort than the ICS/LABA cohort, and mean age, which was slightly higher for the triple-therapy cohort than the ICS/LABA cohort in both the asthma-only and ACO groups ().

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Comorbidities

Comorbidities related to asthma and allergy that occurred in ≥3% of the triple-therapy cohort are shown in . Comorbidities occurring in a higher proportion (≥1.5 times) of patients in the triple-therapy versus ICS/LABA cohorts for both asthma-only and ACO groups, included gastroesophageal reflux (GERD; 27.1% vs 15.8% in the asthma-only cohort and 45.5% vs 26.0% in the ACO group) and pneumonia (8.9% vs 5.7% in the asthma-only cohort and 21.2% vs 9.0% in the ACO group). In the ACO group only, three additional comorbidities occurred in a higher proportion (≥1.5 times) of patients in the triple-therapy versus ICS/LABA cohorts: anxiety disorder (11.1% vs 7.0%, respectively), heart failure (12.1% vs 3.0%, respectively), and atopic dermatitis (11.1% vs 6.0%, respectively). Other common comorbidities, comorbidities related to asthma and allergy that occurred in <3% of the triple-therapy cohort, respiratory symptoms, and tiotropium contraindications, are shown in Supplementary Table S11.

Disease management

In most cases, triple therapy was initiated as a step-up from dual therapy, with most triple therapy initiators (99.6% with asthma only and 94.9% with ACO) using ICS and bronchodilators in the year prior to starting triple therapy (Supplementary Table 2). ICS/LABA was the most common previous treatment across both cohorts; for 99.6% of patients in the asthma-only group and 80.8% of patients in the ACO group it was the last treatment to be used in the year before index (). For both the asthma-only and ACO groups, the proportion of patients who had used high-dose ICS at index was higher in the triple-therapy cohort (asthma only, 68.2%; ACO, 59.1%) than the ICS/LABA cohort (asthma only, 27.6%; ACO, 24.5%) (). The proportion of patients receiving LTRA, theophylline, or any other anti-allergic in the 60 days prior to the index date was also higher for the triple-therapy cohort than the ICS/LABA cohort for both the asthma-only and ACO group.

Table 2. Asthma maintenance treatments in the year prior to initiating triple therapy.

The proportion of patients on twice-daily versus once-daily ICS/LABA in the triple-therapy cohort was lower than in the ICS/LABA cohort. In the triple-therapy cohort, ICS/LABA use at index was twice daily for 68.9% of patients with asthma only and 72.7% with ACO. For the ICS/LABA cohort, the proportion of patients receiving twice-daily ICS/LABA was 82.1% in the asthma-only and 81.0% in the ACO. Use of other medications/treatment is shown in Supplementary Table S11. In the ICS/LABA cohort, over half of all patients (700 patients [53.0%] with asthma only and 52 [52.0%] with ACO) had used LTRA or theophylline concurrently at index or experienced an exacerbation in the year before index.

Disease burden

The proportions of patients with either asthma only or ACO who experienced any exacerbation, who were hospitalized, or who used an exacerbation/symptomatic treatment in the 1 year prior to the index date was consistently higher in the triple-therapy versus ICS/LABA cohort (). Additional data on the use of exacerbation/symptomatic treatments in the year prior to index are shown in Supplementary Table S11.

Triple therapy persistence/adherence

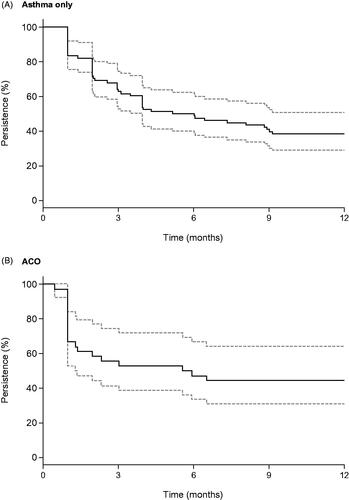

The persistence and PDC for triple therapy were calculated for 78 patients with asthma only and 36 with ACO (variable dose users were excluded, because the number of days of use could not be specified). For the MPR calculation, 57 patients with asthma only and 24 with ACO who were prescribed triple therapy twice or more were included. In the asthma-only group, 62.8% of patients continued triple therapy for ≥3 months, 50% for ≥6 months, and 38.5% for ≥1 year (). In the ACO group, 55.6%, 47.2%, and 44.4% of patients continued triple therapy for ≥3 months, ≥6 months, and ≥1 year, respectively (). The mean (SD) PDC was 0.51 (0.36) in the asthma-only group and 0.51 (0.56) in the ACO group, and the mean (SD) MPR during the triple-therapy period was 0.86 (0.16) in the asthma-only group and 0.92 (0.13) in ACO group.

Figure 3. Triple therapy persistence in the year following the index date. Abbreviations. ACO: asthma-COPD overlap; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Persistence was calculated as the proportion of patients continuing with treatment at a given time point. There was an allowable gap of 90 days. The solid line represents the Kaplan–Meier estimate and the dotted lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

Progress of asthma after starting triple therapy

The proportion of patients with asthma only who developed any exacerbation was lower in the 1 year following initiation of triple therapy compared with the 1 year prior to initiation of triple therapy (45.8% vs 64.0%, respectively), while the proportion of patients who were hospitalized was similar (5.8% vs 6.2%, respectively) (). Similar results were seen for the ACO group; the proportion of patients experiencing any exacerbation was lower in the 1 year following initiation of triple therapy compared with the 1 year prior to initiation of triple therapy (32.3% and 58.6%, respectively), as were the proportion of patients who were hospitalized (5.1% and 9.1%, respectively) (). The number of patients using an inhaled SABA, OCS, injected corticosteroid, injected xanthine or an expectorant was also lower in the year after initiation of triple therapy compared with the prior year (for both asthma only and ACO groups) (). Other medications taken prior to and after index are shown in Supplementary Table S12.

Table 3. Exacerbations, hospitalizations, and medication use before and after initiating triple therapy.

Discussion

In this retrospective, observational cohort study of adults with persistent asthma who initiated triple therapy in 2016, demographics were similar between the triple-therapy and ICS/LABA cohorts. Patients with persistent asthma who initiated inhaled triple therapy received a higher proportion of high-dose ICS and concurrent long-term management medication and had more frequent exacerbations in the year before index than patients with persistent asthma who were prescribed ICS/LABA combination therapy. Comorbidities were similar between the triple-therapy and ICS/LABA cohorts, with the exception of GERD and pneumonia, which were the only comorbidities to occur in a higher proportion of patients in the triple-therapy versus ICS/LABA cohorts in both the asthma-only and ACO groups. For adherence, MPR for triple therapy was relatively high in the subset of patients analyzed. Although persistence started higher in the asthma cohort compared with the ACO cohort, it also dropped by a larger proportion, therefore, after 1 year, persistence was lower for the asthma cohort than the ACO cohort. Finally, the proportion of patients experiencing exacerbations and hospitalizations decreased following initiation of triple therapy for both the asthma-only and ACO groups.

In most cases, triple therapy was initiated as a step-up from dual therapy, with most initiators of triple therapy (99.6% with asthma only and 94.9% with ACO) using ICS and bronchodilators in the year prior to starting triple therapy. Furthermore, around half of the patients in the ICS/LABA cohort had used LTRA or theophylline concurrently at index or experienced an exacerbation in the year before index suggesting a potential need for inhaled triple therapy. Exacerbation rate was high in the triple-therapy cohort, with many patients receiving OCS. This could be due to the inclusion criteria for this study; patients were required to have at least 4 asthma diagnoses in the last year, and patients with intermittent asthma and those who did not rely heavily on medications were excluded. Furthermore, as many patients received ICS/LABA prior to starting triple therapy, it is likely that an exacerbation led to the decision to add a LAMA. In contrast to previous studiesCitation8–10, an overuse of triple therapy for patients with comorbid COPD was not found. A previous retrospective studyCitation11 suggested that triple therapy was initiated for patients who are currently on bronchodilators and are at risk of exacerbations or have continued persistent symptoms, in accordance with accepted treatment recommendationsCitation12, and although the present study did not directly investigate the reasons for initiating triple therapy, the treatment and exacerbation history of patients prior to initiation of triple therapy appear to support these results.

A systematic review by Kew and Dahri investigating the addition of tiotropium to ICS/LABA treatment indicated small improvements in the number of exacerbations requiring OCS; however, these differences did not reach statistical significanceCitation13. These results from this study are consistent with these findings in that the percentage of patients with asthma only experiencing an exacerbation following initiation of triple therapy was 45.8%, compared with 64.0% in the ICS/LABA cohort. However, it should be noted that this study was not designed to investigate the effectiveness of triple therapy.

GERD and pneumonia were more frequently observed in the triple-therapy cohort compared with the ICS/LABA cohort. These comorbidities are known to frequently coexist with cough and exacerbationsCitation14–20, and thus their increased prevalence may be a result of more severe disease in the triple-therapy cohort. In a database study published in 2019, a higher prevalence of GERD and pneumonia was observed in a severe versus non-severe asthma cohortCitation21.

For adherence, MPR in triple therapy was generally high. A previous claims database analysis reported a mean (SD) PDC of 0.267 (0.315) and 0.219 (0.248) for asthma patients receiving fluticasone furoate/vilanterol and fluticasone propionate/salmeterol, respectivelyCitation22. In the present study, during the triple-therapy period, the mean (SD) PDC was 0.51 (0.36) in the asthma-only group and 0.51 (0.56) in the ACO group, and the mean (SD) MPR was 0.86 (0.16) in the asthma-only group and 0.92 (0.13) in ACO group. While the high PDC supports good adherence, the high MPR may indicate that there were no long intervals between prescriptions of triple therapy, which could be the result of the inclusion of patients who visited medical sites regularly. Furthermore, many patients in the triple-therapy cohorts had severe asthma, and it has been reported that patients with severe disease generally have better adherenceCitation23–27. It is also possible that physicians chose to prescribe triple therapy for patients with relatively good adherence on the basis that these patients may be more likely to adhere well to triple therapy. It is also worth noting that the treatment regimen may have been simplified for patients moving from dual to triple therapy (twice-daily to once-daily ICS/LABA on the addition of LAMA), which could have improved adherence. The proportion of patients continuing triple therapy, however, decreased from 62.8% at 3 months after index date to 38.5% at 12 months after index for patients with asthma, and from 55.6% to 44.4% for patients with ACO. Possible reasons for discontinuation may include de-escalation (step-down) due to the disease state becoming stable, adverse drug reactions, insufficient effectiveness, or poor adherence. In post marketing surveillance of tiotropium use in Japan, common reasons for discontinuation (available for 96 patients) included symptom improvement (32.3%), adverse events (21.9%), and ineffectiveness (16.7%).

ICS/LABA therapy is available for asthma in a single inhaler in Japan; however, single-inhaler ICS/LABA/LAMA therapy is only available for the treatment of COPD and not asthma. Tiotropium, the only LAMA approved for treatment of asthma (since 2014)Citation28, needs to be administered via a mist inhalerCitation29 in addition to ICS/LABA, which is supplied as either a dry powder inhaler or pressurized metered dose inhalerCitation30. GINA guidelines advise that the use of multiple devices should be avoided if possible, as it can make treatment use more difficult and lead to patient confusionCitation1, which may result in insufficient control of asthma if treatment is not administered correctlyCitation31. On top of the different treatment devices, some ICS/LABA formulations are used twice daily whilst tiotropium is used once daily, meaning the time at which each treatment is administered will differCitation29,Citation32. Furthermore, the number of inhalations may differ between treatments. For example, fluticasone furoate/vilanterol is one inhalation per use, while tiotropium is two inhalations per useCitation29,Citation32. These factors may further increase treatment complexity.

This study has a number of strengths. A large and widespread study population was investigated, which included patients who visited any physician (specialists or non-specialists) and any medical site (clinics, hospitals, or pharmacies). As of the end of 2018, the JMDC database contained approximately 5.7 million people nationwide. As all Japanese residents are obliged to join a health care insurance societyCitation33, and the benefits offered by the insurance societies included in the JMDC Claims Database do not differ from the benefits provided by other insurers, the database can be considered to be representative of the population.

Limitations of this study include those known to be associated with claims-linked studies. For example, the exclusion of patients who withdrew from the health insurance database may have resulted in the exclusion of patients who died due to severe asthma. However, as the number of deaths related to asthma was relatively low in Japan in the year 2016 (1454 deaths), this was considered unlikely to have had a large impactCitation34. As symptoms and examination values were not included in the database, true severity could not be evaluated. Instead, approximate severity was estimated using ICS daily dose, meaning that severity could only be approximated for patients on a fixed daily ICS dose, and not for patients on a variable ICS dose. Also, for this reason, PDC and MPR could not be calculated for those on a variable dose. Social economic status is not included, but universal health care insurance system in Japan allows all patients to use all drugs regardless of their incomes, ages, or insurers. The lack of information on vaccination and non-prescription drugs, and the accuracy of the diagnosis were also considered as limitations of the claims-linked studies.

Other limitations included the low proportion of elderly people included in the study, possibly because the JMDC database includes claims from employer-sponsored health insurance plans and is therefore likely to include employed patients rather than older retirees, and the lack of data on reasons for discontinuation or switch of treatment. Further studies collecting more detailed information, such as a prospective or medical record review, may be needed to explore these reasons. There were also some limitations regarding the counting of exacerbations; the algorithms used to account for the monthly reporting structure of the claims database meant that it was not possible to determine exactly when an exacerbation event started and ended. Lastly, the definition of triple therapy was restricted to prescription of an ICS, LABA, and LAMA on the same day.

Conclusions

Triple therapy is usually initiated as a step-up from dual therapy in patients with severe persistent asthma through a combination of ICS/LABA + LAMA. In this study of patients from Japan with persistent asthma, adherence after initiation of triple therapy was moderate to high compared with previously reported in real-world evidence studies. Disease control was also good after initiation of triple therapy, with a lower number of exacerbations in both the asthma-only and ACO groups in the year after triple therapy compared with the year prior. The evidence from this study may serve as a reference for the use of inhaled triple therapy for asthma.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The work presented here, including the conduct, conception and design of the study, data analysis and interpretation, was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) (GSK study ID: HO-18-18524). The sponsor was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as well as intellectual property considerations.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors met the criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. All authors are employees of GSK and JFB, KS and TK own stock in GSK. TK is a part-time employee of Shiga University of Medical Science. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Adoair, Diskus, Ellipta, Relvar and Sultanol are owned by or licensed to the GSK group of companies. Airomir is a trademark of Teva Pharmaceuticals International. Berotec is a trademark of Boehringer Ingelheim. Clickhaler is a trademark of M L Laboratories PLC. Flutiform is a trademark of Jagotec AG. Meptin and Swinghaler are trademarks of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Stmerin D is a trademark of Astellas Pharma Inc. Symbicort is a trademark of AstraZeneca AB.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design of the study, the data analysis and interpretation, and writing and reviewing of the manuscript, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (50.1 KB)Acknowledgements

Editorial support in the form of initial preparation of the outline based on input from all authors, and collation and incorporation of author feedback to develop subsequent drafts, assembling tables and figures, copyediting, and referencing was provided by Chloe Stevenson, MSci, of Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK, and was funded by GSK.

Data availability

GSK makes available anonymized individual participant data and associated documents from interventional clinical studies which evaluate medicines, upon approval of proposals submitted to www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com. To access data for other types of GSK sponsored research, for study documents without patient-level data and for clinical studies not listed, please submit an enquiry via the website.

References

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Fontana: GINA; 2019.

- GBD 2015 Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:691–706.

- Fukutomi Y, Nakamura H, Kobayashi F, et al. Nationwide cross-sectional population-based study on the prevalences of Asthma and Asthma Symptoms among Japanese Adults. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;153(3):280–287.

- Japanese Society of Allergology. Japanese guidelines for adult asthma 2017. Allergol Int. 2017;66:163–189.

- Japanese Society of Allergology. Japanese guidelines for adult asthma 2018. Tokyo: Kyowa kikaku Ltd.; 2018.

- Global Initiative for Asthma and Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. diagnosis of diseases of chronic airflow limitation: asthma copd gina gold. Fontana: GINA and GOLD; 2015.

- Yayan J, Rasche K. Asthma and COPD: similarities and differences in the pathophysiology, diagnosis and therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;910:31–38.

- Brusselle G, Price D, Gruffydd-Jones K, et al. The inevitable drift to triple therapy in COPD: an analysis of prescribing pathways in the UK. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2207–2217.

- Simeone JC, Luthra R, Kaila S, et al. Initiation of triple therapy maintenance treatment among patients with COPD in the US. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;12:73–83.

- Hurst JR, Dilleen M, Morris K, et al. Factors influencing treatment escalation from long-acting muscarinic antagonist monotherapy to triple therapy in patients with COPD: a retrospective THIN-database analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:781–792.

- Bogart M, Stanford RH, Reinsch T, et al. Clinical characteristics and medication patterns in patients with COPD prior to initiation of triple therapy with ICS/LAMA/LABA: A retrospective study. Respir Med. 2018;142:73–80.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Managament, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease – 2019 Report. 2019.

- Kew KM, Dahri K. Long‐acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) added to combination long‐acting beta2‐agonists and inhaled corticosteroids (LABA/ICS) versus LABA/ICS for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2016;2(1):CD011721.

- Ing AJ. Cough and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2004;17(6):403–413.

- Ioachimescu OC, Desai NS. Nonallergic triggers and comorbidities in asthma exacerbations and disease severity. Clin Chest Med. 2019;40(1):71–85.

- Jackson DJ, Sykes A, Mallia P, et al. Asthma exacerbations: origin, effect, and prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(6):1165–1174.

- Nordenstedt H, Nilsson M, Johansson S, et al. The relation between gastroesophageal reflux and respiratory symptoms in a population-based study: the Nord-Trøndelag health survey. CHEST. 2006;129(4):1051–1056.

- Novelli F, Latorre M, Vergura L, et al. Asthma control in severe asthmatics under treatment with omalizumab: a cross-sectional observational study in Italy. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2015;31:123–129.

- Shirai T, Mikamo M, Tsuchiya T, et al. Real-world effect of gastroesophageal reflux disease on cough-related quality of life and disease status in asthma and COPD. Allergol Int. 2015;64(1):79–83.

- Wedzicha JA, Seemungal TA. COPD exacerbations: defining their cause and prevention. Lancet. 2007;370(9589):786–796.

- Inoue H, Kozawa M, Milligan KL, et al. A retrospective cohort study evaluating healthcare resource utilization in patients with asthma in Japan. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2019;29:13.

- Atsuta R, Takai J, Mukai I, et al. Patients with Asthma prescribed once-daily fluticasone Furoate/Vilanterol or twice-daily fluticasone Propionate/Salmeterol as maintenance treatment: analysis from a Claims Database. Pulm Ther. 2018;4(2):135–147.

- Cramer JA, Bradley-Kennedy C, Scalera A. Treatment persistence and compliance with medications for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Can Respir J. 2007;14(1):25–29.

- Howell G. Nonadherence to medical therapy in asthma: risk factors, barriers, and strategies for improving. J Asthma. 2008;45(9):723–729.

- Latry P, Pinet M, Labat A, et al. Adherence to anti-inflammatory treatment for asthma in clinical practice in France. Clin Ther. 2008;30(Spec No):1058–1068.

- Laforest L, Licaj I, Devouassoux G, et al. Factors associated with early adherence to tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron Respir Dis. 2013;10(1):11–18.

- Tanaka K, Kamiishi N, Miyata J, et al. Determinants of long-term persistence with tiotropium bromide for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Copd. 2015;12:233–239.

- Asthma: Spiriva® (tiotropium) Respimat® becomes the only LAMA licensed in asthma care 2014. Available from: https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/news/27112/asthma-spiriva-tiotropium-respimat-becomes-lama-licensed-asthma-care/.

- Boehringer Ingelheim. SPIRIVA RESPIMAT prescribing information. Germany: Boehringer Ingelheim; 2004.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Pocket Guide for Asthma Management and Prevention. Fontana: GINA; 2019.

- Melani AS, Bonavia M, Cilenti V, et al. Inhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease control. Respir Med. 2011;105(6):930–938.

- Northern Ireland Formulary. 3.2b Compound ICS/LABA Preparations – [Asthma] 2018; [cited 2019 Aug 01]. Available from: http://niformulary.hscni.net/Formulary/Adult/3.0/3.2/3.2b/Pages/default.aspx.

- Sakamoto H, Rahman M, Nomura S, et al. Japan health system review. New Delhi: World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2018. 2018. en.

- Number of deaths by sex and rate according to the year-by-year classification of cause of death [Internet]. 2017; [cited 2019 Aug 02]. Available from: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/dbview?sid=0003214720.