Abstract

Objective

To quantify the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and economic burden of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Methods

Studies were searched through Embase, MEDLINE, PubMed, and Cochrane Library, as well as conference abstracts (1 January 2000–2 June 2019).

Results

Overall, 12 and 17 primary studies were included in the HRQoL and economic burden reviews, respectively. Patients with CLL reported impairment in various quality of life domains when compared with healthy controls, including fatigue, anxiety, physical functioning, social functioning, depression, sleep disturbance, and pain interference. Key factors associated with a negative impact on the HRQoL burden of CLL included female gender, increased disease severity, and the initiation of multiple lines of therapy. Economic burden was assessed for patients with CLL based on disease status and the treatment regimen received. The main cost drivers related to CLL were outpatient and hospitalization-related costs, primarily incurred as a result of chemo/chemoimmunotherapy, adverse events (AEs), and disease progression. Treatment with targeted agents, i.e. ibrutinib and venetoclax, was associated with lower medical costs than chemoimmunotherapy, although ibrutinib was associated with some increased AE costs related to cardiac toxicities. Cost studies of targeted agents were limited by short follow-up times that did not capture the full scope of treatment costs.

Conclusions

CLL imposes a significant HRQoL and economic burden. Our systematic review shows that an unmet need persists in CLL for treatments that delay progression while minimizing AEs. Studies suggest targeted therapies may reduce the economic burden of CLL, but longer follow-up data are needed.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common form of leukemia in the Western hemisphere, representing 37% of all leukemia cases in the United States in 2019Citation1. It has an estimated prevalence of 48.0 per 100,000 personsCitation2 and an age-adjusted incidence of 4.5 per 100,000/year in the United StatesCitation3. CLL is most often diagnosed in the elderly (median age at diagnosis: 68 years), and the incidence is nearly twice as high in men as in womenCitation3.

As CLL is an indolent disease, a “watch and wait” approach is recommended for patients with asymptomatic, early-stage CLL, and treatment is initiated in patients with symptomatic, active diseaseCitation4,Citation5. Treatments are non-curative and depend on individual diagnosis and progressionCitation6,Citation7. Until recently, the standard of care for first-line and relapsed/refractory (R/R) treatment of CLL has been chemoimmunotherapy regimens such as fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR); bendamustine + rituximab (BR); or chlorambucil + obinutuzumabCitation6,Citation8. Novel targeted therapies, in the form of Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors (ibrutinib and acalabrutinib) and venetoclax, a BCL2 inhibitor, have revolutionized the CLL treatment landscape and are fast becoming standard of care options in CLLCitation9,Citation10.

With a fast-evolving treatment landscape, it is important to understand the burden of CLL on patients and healthcare systems, as well as the impact of therapy. The objective of this review was to summarize the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and economic burden of CLL published in observational studies through a systematic review of the literature.

Methods

An electronic search for relevant publications was performed using Embase, MEDLINE, PubMed, and Cochrane Library. Conference abstracts were searched to retrieve the latest studies that have not yet been published. Comprehensive search strategies, developed in accordance with the systematic searching best practice guidance published by the Cochrane CollaborationCitation11, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines NetworkCitation12, and health technology assessment agencies (e.g. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], Scottish Medicines Consortium [SMC], and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ]), were used to identify all relevant studies (Supplementary Information).

To be included in the review, studies had to meet the following criteria: observational studies of adult patients (≥18 years) with CLL and published between 1 January 2000 and 2 June 2019. For the HRQoL review, cohort studies reporting HRQoL or patient-reported outcome data were included. For the economic review, cost consequence studies, cost studies, surveys, and analyses; database studies collecting cost data (e.g. claims databases and hospital records); and resource surveys were included. Pharmacoeconomics studies and non-English studies were excluded but there was no restriction on countries where the study was conducted.

This systematic review was performed according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-AnalysesCitation13.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently assessed the eligibility of all identified citations using a three-step process. Any discrepancies between reviewers were reconciled by a third independent reviewer. Citations were first screened based on the abstract supplied. Citations that did not match the eligibility criteria were excluded; where unclear, citations were included. Full-text copies of all references that could potentially meet the eligibility criteria were obtained. The eligibility criteria were then applied to these; data presented in the studies included after this stage were extracted into data-extraction grids. Where more than one publication was identified describing a single trial, data were compiled into a single entry in the data-extraction table to avoid double counting of patients and studies. Each publication was referenced in the table to recognize that more than one publication may have contributed to the entry.

Results

HRQoL burden of CLL

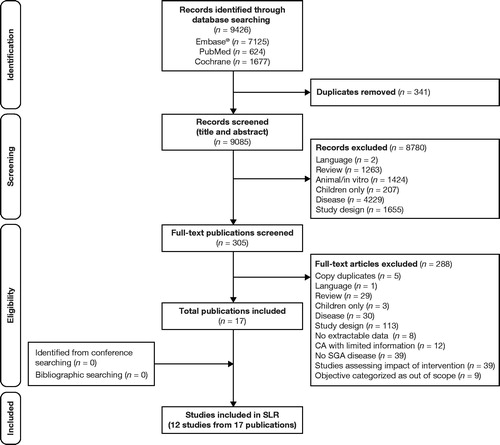

The initial screening retrieved 9426 citations, and following the data-extraction process, 12 primary studies (reported in 17 publications) were included in the HRQoL burden review (). The 12 studies differed in terms of design, study populations, and the instruments used to measure HRQoL burden ()Citation14–30. The majority of studies were conducted in the United States (n = 6) and Europe (n = 3); study populations included both treated and untreated patients, as well as those with R/R disease. Only one of the instruments used to measure HRQoL, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Leukemia (FACT-Leu) questionnaire, has been validated in patients with CLLCitation31 (). HRQoL outcomes were categorized based on the comparison of these patients with other populations, baseline variables, and active versus “watch and wait” treatment. Notably, only one study identified examined HRQoL in family caregivers of patients with leukemia (not limited to CLL) in ChinaCitation14. The study found lower EQ-5D-3L scores in caregivers than in the general population, indicating poorer HRQoLCitation14.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart of the HRQoL burden review of CLL. Abbreviations. CA, conference abstract; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; SGA, subgroup available; SLR, systematic literature review.

Table 1. Overview of studies included in the HRQoL burden review of CLL.

Table 2. Instruments used to assess HRQoL in patients with CLL.

HRQoL of patients with CLL versus other populations

Comparison with the general population

Four studies compared HRQoL outcomes among patients with CLL with those among general population norms ()Citation15–17,Citation19. Overall, patients with CLL had substantially worse HRQoL than the general population in terms of fatigue, anxiety, physical functioning, social functioning, depression, sleep disturbance, and pain interferenceCitation15,Citation16,Citation19.

In Austria, a 1-year prospective survey of HRQoL in patients with CLL found that global HRQoL (assessed using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment Quality of Life Questionnaire [EORTC QLQ-C30]) was statistically similar between these patients and age- and gender-matched healthy controls (n = 76 and n = 152, respectively)Citation15. The median age of patients with CLL in the survey was 68 years, compared with 67 years in healthy controls; 56% had not been exposed to treatment. Despite similarities in global HRQoL scores, patients with CLL reported lower HRQoL in almost all domains, which was significant in the areas of physical (p < .001) and role (p < .01) functioning, and made more complaints regarding fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and appetite loss, than healthy controls (all p < .001)Citation15. Separately, a web-based survey by Shanafelt et al. conducted across 34 countries reported comparable or improved physical, social/family, functional, and overall HRQoL by EORTC QLQ-C30 scores for patients with CLL (N = 1482) compared with general population normsCitation16. The median age of patients in the survey was 59 years and the majority (60.7%) were untreated, suggesting a population of healthy patients with less severe CLL disease. Emotional wellbeing FACT-General (FACT-G) scores were dramatically lower for patients with CLL than in the general population (p < .001), indicating a psychological burden of CLL even in patients who might be in good physical health. Patients with CLL also reported greater fatigue than the general population (Brief Fatigue Inventory [BFI] scores 2.8 vs. 2.2, respectively; p < .001)Citation16.

Other studies have identified HRQoL deficits among patients with CLL compared with the general populationCitation17,Citation19. In a Netherlands-based study, patients with CLL showed compromised HRQoL across all stages of treatment – including at pre-treatment – compared with age- and gender-matched healthy controlsCitation17. This Dutch cohort of patients with CLL scored statistically worse than healthy controls on the visual analog scale (VAS) and EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D) utility scores, all of the EORTC QLQ-C30, and in symptoms of fatigue, dyspnea, sleeping disturbance, appetite loss, and financial difficultiesCitation17. A cross-sectional study of 134 patients with CLL enrolled in a US cancer registry used the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS-29 v2.0) to assess the distress associated with CLL and its impact on HRQoL across seven domains, comprising physical function, anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbance, ability to participate in social roles and activities, and pain interferenceCitation18,Citation19. Patients with high-risk CLL (risk level captured through patient recall of physician’s explanation of their estimated risk) had significantly higher levels of overall distress (mean [standard deviation (SD)] 31 [23]) than patients with low- or intermediate-risk CLL (21 [16]; p = .029)18. Over a third (37%) of patients were undergoing a “watch and wait” approach, 6% were receiving their first treatment, 12% were in active second or subsequent therapy, and 29% were in remissionCitation19. Compared with the general US population, patients with CLL reported substantially worse HRQoL in terms of anxiety, fatigue, physical functioning, social functioning, depression, sleep disturbance, and pain interferenceCitation19.

Comparison with other cancer types

Studies comparing the impact of CLL on HRQoL with that of other cancers suggest that CLL may compromise certain aspects of HRQoL more than other cancersCitation16,Citation20. While total HRQoL scores on the EORTC QLQ-C30 were broadly similar across cancer types (CLL, Hodgkin’s disease, breast cancer, and bone marrow transplantation) in a single-center Austrian study, patients with CLL had significantly lower physical functioning (73 vs. 85–89) and role functioning (68 vs. 75–87) scores, and lower FACT scores, than patients with other cancersCitation20. Emotional functioning was also more impeded among patients with CLL, compared with published data from other cancer patients, across all stages of disease (p < .001)Citation16.

HRQoL of patients with CLL with active treatment versus untreated patients

Two studies compared outcomes between patients on active treatment versus “watch and wait”. In a US-based cross-sectional study in 107 patients with CLL, Levin et al. found no statistical differences in depression (Beck Depression Inventory [BDI]-II), anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory [BAI]), and physical/mental quality of life (QoL) (Short Form Health Survey-36 [SF-36]) scores between “watch and wait” patients and those in active treatment periods, despite the latter having later-stage diseaseCitation21. Younger “watch and wait” patients (≤60 years) reported more depression (BDI-II; p = .014), worse emotional (FACT-G; p = .0001) and social QoL (FACT-G; p = .002), and higher levels of anxiety (BAI; p = .052) than older patients (>60 years) on active treatmentCitation21. Notably, 25% of patients in the “watch and wait” population were taking anxiety medications compared with 15% of patients on active treatment, although the reasons for being on these medications were not elucidated in the publication. A longitudinal study in the Netherlands found that the “watch and wait” approach was associated with better HRQoL outcomes, in terms of EQ-5D VAS and utility scores, emotional and social functioning, fatigue, dyspnea, losing weight, changes in temperature, feeling apathetic, lack of energy, respiratory infections, and risk of infections, compared with active treatment (e.g. chlorambucil)Citation17. However, the majority of “watch and wait” patients in this study (95%) had low-risk CLL (i.e. Binet Stage A) compared with 68% of active-treatment patientsCitation17.

Shanafelt et al. also reported that patients who had received CLL treatment (chemotherapy and/or monoclonal antibody) had higher fatigue scores (based on BFI) than untreated patients (3.2 vs. 2.5 [p < .001] and 3.8 vs. 2.7 [p < .001], respectively)Citation16. Active treatment was significantly associated with worse anxiety, whether first-line or subsequent therapy (both p < .05) in a US-based survey of patients with CLLCitation19. Second- or subsequent-line therapy was significantly associated with worse physical (p < .05) and social functioning (p < .05), and higher levels of fatigue (p < .01), depression (p < .05), and sleep disturbance (p < .01) in patients with CLLCitation19. An association between HRQoL decline and additional lines of therapy was reported in a prospective analysis of US registry data where FACT-Leu total scores of 136.3, 133.4, and 129.8 were observed in patients initiating first-, second-, and higher-line therapy, respectively (p < .05)Citation22.

We did not find any real-world studies that described HRQoL in patients receiving targeted therapies.

Impact of gender, age, and disease stage on HRQoL

Across studies included in the review, the mean age of patients with CLL ranged from 59–70 yearsCitation15–18,Citation21,Citation23,Citation26–29 and the proportion of male patients varied from 46% to 70%Citation15,Citation17,Citation21,Citation23,Citation26–28. Four primary studies investigated the impact of genderCitation15,Citation16,Citation21,Citation26 and four investigated the impact of ageCitation15,Citation16,Citation21,Citation24 on HRQoL in patients with CLL. Only three studies reported CLL staging of the populations examinedCitation15,Citation16,Citation23.

In the four studies that evaluated the impact of gender on HRQoL in CLL, the data generally suggested that females with CLL experienced greater levels of fatigue and poorer functioning in physical and/or emotional domains than their male counterpartsCitation15,Citation16,Citation25,Citation26, although gender was not always a reliable predictor of HRQoL outcomesCitation21. In Austria, a 1-year longitudinal study of HRQoL in patients with CLL found that females reported substantially lower HRQoL than males in each EORTC QLQ-C30 functioning subscale (including fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain, appetite loss, constipation, and financial impact)Citation15. The HRQoL effect size was largest for emotional functioning (1.04) and smallest for cognitive functioning (0.35)Citation15. These findings were echoed in a US CLL registry study of 1140 patients with CLL. Females reported higher levels of fatigue (BFI global scores: 4.6 vs. 4; p < .0001) and problems with pain/discomfort (p = .0077), usual activities (p = .0015), anxiety/depression (p = .0117), and worse overall fatigue (p < .0001), fatigue severity (p < .0001), and fatigue-related interference (p = .0005) on the EQ-5D scale within 2 months following treatment initiationCitation26. No significant differences were observed in the EQ-5D domains of mobility and self-care or in mean overall general HRQoL as measured by the EQ-5D VASCitation26. In contrast, in a US-based cohort of patients with CLL, Levin et al. did not find that gender predicted any of the QoL outcomes examined in their analysis, including SF-36, FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lymphoma (FACT-Lym), BAI, and BDI-IICitation21.

Four studies in our analysis evaluated the effect of age on HRQoL, with mixed outcomes across domains/subscalesCitation15,Citation16,Citation21,Citation24. EQ-5D results from a US prospective observational registry study showed impaired mobility in patients with CLL aged ≥75 years compared with younger patients (p < .0001), while usual activities (p = .0009) and pain/discomfort (p < .0001) were worse in those <65 and ≥75 years compared with those aged 65–74 yearsCitation24. Notably, patients aged 65–74 years had higher FACT-Leu scores than those aged <65 years and ≥75 years indicating better self-reported overall HRQoL. A US cross-sectional study by Levin et al. showed that younger patients (≤60 years) performed better in terms of the SF-36 physical component score (p = .0001) and physical functioning (p = .009) component scores but worse on mental health component scores, including depression, emotional, and social domainsCitation21. A longitudinal study in Austrian patients with CLL found that older patients reported lower HRQoL over 1 year than younger patients in the EORTC QLQ-C30 physical functioning and role functioning scalesCitation15. In a multivariate analysis, Shanafelt et al. found FACT-G scores for emotional and overall wellbeing were associated with older age in patients with CLLCitation16.

We identified three studies that evaluated the impact of disease stage (assessed by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] or Rai/Binet scores) on HRQoLCitation15,Citation16,Citation23. Shanafelt et al. reported that FACT-G scores for physical, functional, and overall wellbeing were significantly lower among patients with CLL with more advanced diseaseCitation16, while Pashos et al., using US-based registry data, found that EQ-5D total and domain scores (pain/discomfort, mobility, and usual activities) worsened with ECOG severityCitation23. Similarly, BFI scores increased with disease severity, suggesting fatigue increases with disease severityCitation15,Citation16,Citation23.

Economic burden of CLL

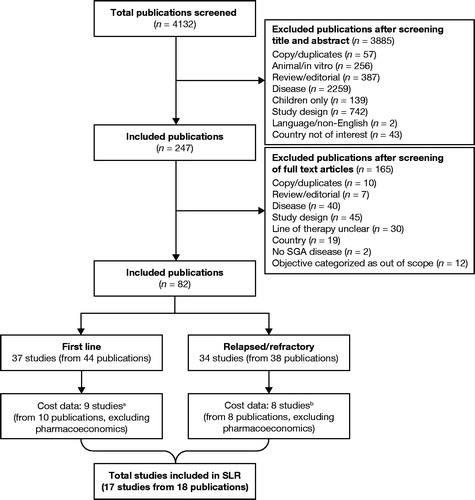

The initial screening process retrieved 4132 citations on the economic burden of CLL. Following the data-extraction process, 17 primary studies were included in the review (), of which nine assessed the burden among first-line patients and eight assessed R/R patients.

Figure 2. Flowchart of the economic burden review of CLL. aIncludes one studyCitation7 that analyzed data from a mixed population of patients with CLL with treatment failure. bIncludes one studyCitation41 that analyzed data from a mixed population of patients who had received ≥1 CLL-directed treatment. Abbreviations. CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; SGA, subgroup available; SLR, systematic literature review.

Costs related to frontline CLL therapy

Of the nine studies reporting cost and resource use among patients with CLL receiving first-line treatment, eight were conducted in the United States ()Citation7,Citation32–40.

Table 3. Overview of studies reporting cost and resource use data among first-line patients with CLL.

Direct costs incurred during frontline CLL therapy

A US claims-based study by Matasar et al. examined total healthcare costs over a 9-month period in 707 patients with CLL (mean age, 70 years) and at least one claim for a National Comprehensive Cancer Network-recommended systemic cancer therapy between 2013 and 2015Citation32. The most common frontline regimens included BR (26%), ibrutinib (14%), FCR (9%), and chlorambucil + obinutuzumab (7%). Mean duration of therapy varied according to the regimen, the longest being 6.7 months for ibrutinib (standard deviation 4.8 months), as a result of continuous treatmentCitation32. The overall treatment costs were highest for FCR (mean cost per patient, US$125,839) and lowest for chlorambucil + obinutuzumab (mean cost per patient, US$67,119)Citation32.

Another US database study compared health resource utilization (HRU) in 1795 patients with CLL treated with BR (n = 944) or FCR (n = 843) between 2005 and 2015Citation33. Despite being significantly older (mean age, 66 years for BR vs. 60 years for FCR) and having more frequent comorbid conditions (mean Charlson comorbidity score, 3.1 for BR vs. 2.7 for FCR), the BR cohort experienced significantly fewer outpatient visits (14.1 vs. 17.0, respectively; p < .05), and was less likely to experience an emergency room (ER) visit (odds ratio [OR]: 0.66; p < .05) or a hospitalization (OR: 0.60; p < .05) than patients receiving FCRCitation33. The study concluded that patients aged ≥70 years and receiving FCR experienced significantly more hospitalization days, outpatient visits, and ER visits than patients of the same age who were treated with BRCitation33.

A retrospective analysis of claims data from a National US database (2007–2013) examined 946 patients receiving systemic anticancer therapy in first-line treatment of CLL (mean age, 68 years; 63% males)Citation34. The most commonly used regimens were FCR (19%), rituximab monotherapy (19%), and BR (18%). HRU was markedly lower among patients receiving rituximab monotherapy compared with FCR and BR (67% vs. 83% and 83% [outpatient visits]; 21% vs. 32% and 37% [ER visits]; and 15% vs. 25% and 33% [inpatient stays] for rituximab, FCR, and BR, respectivelyCitation34.

Delgado et al. used a chart review to assess HRU in fludarabine-ineligible patients treated with chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy in three countries between 2011 and 2012 (n = 94, n = 127, and n = 121 in the UK, Spain, and Italy, respectively)Citation35. Chlorambucil monotherapy was the most commonly prescribed regimen given to these patients (59.6%, 38.6%, and 30.6% of patients in the UK, Spain, and Italy, respectively), with BR the next most common regimen in the UK and Italy (17.0% and 23.1%, respectively) and chlorambucil + rituximab in Spain (18.9%)Citation35. Hospitalizations were found to be the highest drivers of cost with the UK and Spain reported to have the highest rates of hospitalization (40% per country) while Italy had the lowest (27%)Citation35. However, UK and Spanish patients tended to be older than Italian patients (mean age, 76, 77, and 74 years, respectively)Citation35.

Economic impact of targeted therapy on frontline CLL

Three studies assessed the economic impact of frontline CLL treatment using targeted agentsCitation36–38. All three studies were US-based and evaluated the impact of ibrutinib on HRU and costs. A database study by Wang et al. assessed HRU over a 24-month follow-up period in patients initiating treatment with either ibrutinib (n = 322), chemoimmunotherapy (n = 839), or BR (n = 455)Citation36. Patients were reported to be similar in baseline characteristics (no data provided)Citation36. Single-agent ibrutinib resulted in a net reduction in overall healthcare costs compared with BR (monthly reduction of US$5569; p < .0001), despite higher pharmacy costs (mean monthly cost difference of US$7002; p < .0001), as a result of lower medical costs (mean monthly cost difference of US$12,571; p < .0001)Citation36. Similarly, ibrutinib resulted in a reduction in net monthly total healthcare costs of US$3766 compared with chemoimmunotherapy (p < .0001)Citation36. A large database study analyzed HRU in 8008 patients with CLL, including 4368 treated with ibrutinib, 1464 treated with chemotherapy, and 2176 treated with chemoimmunotherapy treated between 2014 and 2017. Ibrutinib-treated patients tended to be slightly younger than chemotherapy-treated patients (mean age at diagnosis, 66 vs. 68 years) but older than chemoimmunotherapy patients (mean age at diagnosis, 62 years). Patients receiving chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy had significantly higher mean medical costs compared with ibrutinib for office visits (US$190 vs. US$304 vs. US$515 for ibrutinib, chemotherapy, and chemoimmunotherapy, respectively; p < .0001) and outpatient visits (US$1373 vs. US$1614 vs. US$2753, respectively; p < .0001)Citation37. ER visits were also statistically significantly higher for chemotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy than ibrutinib (numbers not reported)Citation37. However, ibrutinib was associated with higher rates of atrial fibrillation than chemoimmunotherapy (4.4% vs. 2.7% (p = .0005)Citation37. A separate database study of 1086 patients with CLL receiving front-line therapy between 2014 and 2016 found that ibrutinib-treated patients (n = 178) had lower inpatient costs per month (US$1480 vs. US$1981; p = .004) and fewer office visits per month (1.8 vs. 5.7; p < .0001) compared with those receiving chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy (n = 908) after the first cycle of therapy.Citation38 Ibrutinib-treated patients in this study were reported to be similar to chemotherapy- and chemoimmunotherapy-treated patients in age (median, 65 years), gender (64% males) and geographic location.

A linked analysis of the claims-based study by Matasar et al.Citation32 found no significant differences in mean costs associated with ER visits (US$389–526) and inpatient stays (US$4360–10,016) between ibrutinib and chemoimmunotherapy agents over a 9-month periodCitation39. Overall treatment costs were lower with ibrutinib (mean [SD], US$96,861 [38,568]) than with FCR (US$126,019 [88,896]) and BR (US$101,072 [$51,510]) but higher than with chlorambucil + obinutuzumab (US$67,429 [54,080])Citation39. Ibrutinib costs were driven by drug costs as a result of continuous therapy, whereas treatment costs for finite intravenous therapies stabilized over the 9-month follow-up period (range US$25,721–43,184)Citation39.

Economic burden of adverse events

The economic burden associated with managing specific adverse events (AEs) associated with commonly used first-line CLL treatment regimens (FCR, BR, chlorambucil, fludarabine + rituximab, or rituximab) was found to be substantial in a retrospective US claims data analysis (N = 2035) from 2005 to 2012Citation40. Specific AEs included infusion reactions (40%), anemia (35%), infection (26%), dyspnea (9%), neutropenia (8%), febrile neutropenia (5%), thrombocytopenia (2%), and leukopenia (1%)Citation40. An analysis of AE costs adjusting for patient baseline characteristics found that infusion reactions (mean [95% confidence interval (CI)], US$4482 [4141–4862]), myelotoxicity (neutropenia [US$5406 (4629–6367)], thrombocytopenia [US$12,621 (8933–18,651)], anemia [US$8894 (8267–9586)], collectively) and infection (US$7163 [6648–7733]) were the most costly AEs from diagnosis to end of therapyCitation40. A separate US claims database analysis of 7639 patients with CLL treated between 2012 and 2015 found that the risk of inpatient admission was seven times greater in patients who experienced three to five AEs during first-line CLL treatment. BR was the most common frontline regimen (28%) while ibrutinib was the most commonly used second- and third-line regimen (21% and 26%, respectively)Citation41. The most commonly reported AEs in BR-treated patients were neutropenia (58%), infections (36%), and anemia (35%), while infections (38%), anemia (35%) and dyspnea (25%) were the most commonly reported AEs in ibrutinib-treated patientsCitation41. AEs that resulted in significantly higher monthly all-cause costs in first-line therapy, compared with the absence of respective AEs, included anemia (cost ratio [95% CI], 1.70 [1.48–1.96]), infection (1.17 [1.0–1.36]), neutropenia (1.18 [1.02–1.37]), and pneumonia (1.32 [1.02–1.72])Citation41. The AE cost ratios for second- and third-line therapy were not reportedCitation41. Finally, Nabhan et al. reported that ibrutinib-treated patients with cardiovascular events had higher HRU than ibrutinib-treated patients without cardiovascular events (outpatient visits: 3.9 vs. 3.5 [p < .0001]; office visit: 1.0 vs. 0.9 [p < .0048]; and length of inpatient stay 3.2 vs. 2.6 [p < .0001])Citation37.

Costs related to patients with R/R CLL

Of the eight observational studies that reported cost and resource use among patients with R/R CLL, six were conducted in North America ()Citation41–48.

Table 4. Overview of studies reporting cost and resource use data among R/R patients with CLL.

HRU data were collected in a retrospective study of medical chart data from 86 patients with R/R CLL (mean age, 65 years; 69% males) undergoing treatment in two facilities in Canada between 2002 and 2012Citation42. Of the total population studied, 44.2% (38/86) were receiving fludarabine-based treatments and 48.8% (42/86) were receiving chlorambucil-based CLL treatments. Over a mean follow-up period of 4.7 years, the mean total cost per patient (regardless of follow-up) in Canadian dollars (CAN$) was CAN$25,736 with costs highest for patients with Rai Stage IV diseaseCitation42. Chlorambucil-treated patients had higher mean costs per patient than fludarabine-treated patients (CAN$15,783 vs. CAN$5770), which was attributed to chlorambucil-treated patients remaining on treatment longerCitation42.

In another Canada-based study, HRU was examined in an analysis of previously treated patients (N = 60) with R/R CLL diagnosed with CLL between 2006 and 2012 (median age at diagnosis, 65 years; 71% male)Citation43. CLL treatment costs and AEs accounted for nearly half the total costs reported (per-patient costs of CAN$11,248 and CAN$11,170, respectively). Male patients had higher costs CAN$24,926 (vs. CAN$17,938 for female patients), and those with more advanced disease (Rai Stage IV) or p53 mutations also had higher associated treatment costs (CAN$43,927 per patient and CAN$40,840 respectively)Citation43. Previous treatment with fludarabine in first-line was credited with driving up treatment costs in these patients compared with previous treatment with chlorambucil (CAN$27,940 vs. CAN$17,201, respectively)Citation43.

In a Europe-based chart review conducted in centers across France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom, HRU between 2002 and 2008 was examined in 37 patients with fludarabine-refractory CLL who were also refractory to, or ineligible for, alemtuzumab treatmentCitation44. Over 24 months of follow-up, patients made an average of 0.8 ER visits and 1.9 inpatient stays lasting for an average of 11.2 daysCitation44. The most common single-agent treatment regimens were alemtuzumab (38%) and methylprednisolone (19%); combination therapies were most often rituximab (43%) in combination with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone; 16%), fludarabine/cyclophosphamide (11%), and bendamustine (8%)Citation44. Data from a 2009 medical chart review in a subgroup of 12 Spanish patients with CLL refractory to fludarabine- or alemtuzumab-containing regimens found that these patients incurred substantial direct medical costs (EUR 46,613 per patient)Citation45. Hospital stays and physician visits were identified as key drivers of total costs, accounting for 48% of total costsCitation45.

In a retrospective cohort analysis of US claims data from a pre-treated, elderly patient population with CLL (N = 275; mean age, 75 years; >60% male), bendamustine monotherapy was compared with BR combination therapy when given as a second- or later-line of therapyCitation46. Total, all-cause healthcare costs (including inpatient, ER, outpatient, and CLL drug costs) that incurred during relapsed treatment with bendamustine-based regimens were high and broadly comparable across regimens (US$14,520 and US$13,125 per patients per month [PPPM] for BR and bendamustine cohorts, respectively) with a large portion driven by comorbidity and/or AE-related costs (58–67%)Citation46.

Treatment costs in patients with R/R CLL were also examined in a US-based analysis of the Truven Health MarketScan database. The study cohort comprised patients with CLL diagnosed between 2004 and 2013 who were unfit for chemotherapy (n = 18,776), of whom 1109 were both unfit and relapsed (U/R) (i.e. treated with ≥2 lines of antineoplastic therapy where the second line represented a change in therapy)Citation47. U/R patients were mostly male (63%) with a mean age of 63 yearsCitation47. The most commonly prescribed first-line regimens in U/R patients included rituximab ± prednisone/dexamethasone (24.0%), BR ± prednisone/dexamethasone (9.6%), and FCR ± prednisone/dexamethasone (7.2%)Citation47. First- and second-line PPPM total costs (SD) were considered substantial for U/R patients at US$15,907 ($19,893) and US$18,506 ($36,977) for unfit and relapsed patients, respectivelyCitation47.

In an aforementioned US claims analysis of 7639 patients with CLL, ibrutinib was the most commonly used second-line treatment optionCitation41. Ibrutinib was associated with higher per-patient costs than chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy (mean [SD] monthly per-patient cost, US$21,766 [US$36,140] for ibrutinib monotherapy, US$14,640 [US$12,925] for BR, US$12,742 [US$15,994] for FCR, and US$12,575 [US$18,072] for rituximab monotherapy)Citation41. The study reported that per-patient costs were driven by care setting, treatment regimen, and the number of AEs, but did not elucidate the exact contribution of each of these factors to per-patient costsCitation41.

Finally, a US database study compared the economic impact of venetoclax (n = 154) vs. chemotherapy (n = 121) and chemoimmunotherapy (n = 110) in patients with R/R CLL between 2016 and 2018Citation48. Patients were reported to be similar in age (mean, 64–70 years) and gender (no data provided)Citation48. The median follow-up from initiation of second-line treatment was significantly shorter for venetoclax-treated patients compared with chemotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy groups (7.7 months vs. 16.2 and 18.6 months, respectively; p < .0001)Citation48. The total medical costs were significantly higher in both the chemotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy groups compared with venetoclax (US$6076 and US$5515, respectively, vs. US$2440; p < .0001), mainly because of higher inpatient and outpatient costsCitation48. Drug-related costs were not included in this analysisCitation48.

Discussion

Pfeil et al. reported that the number of hospitalizations and referrals in patients with CLL in the United Kingdom has increased significantly over a 13-year periodCitation49. In the United States, Lafeuille et al. reported that the average lifetime Medicare cost per patient with CLL was US$40,000 higher than the lifetime cost of a patient without cancerCitation50. Our systematic review found that CLL continues to impose a significant burden on patients and healthcare systems, with standard of care chemoimmunotherapeutic agents doing little to alleviate the burden. Patients with CLL experienced worse HRQoL than the general population across several domains, including symptoms (e.g. fatigue and sleep disturbances), as well as physical and mental functioningCitation15–17,Citation19. Although CLL mostly afflicts men, women appeared to experience worse HRQoL than menCitation15,Citation16,Citation26. The impact of age on HRQoL in these patients was unclear, with the elderly performing worse in physical functioning across studies but better than younger patients in mental functioning in some studiesCitation15,Citation16,Citation21,Citation24. However, HRQoL was clearly worse with an increase in disease severity, regardless of ageCitation15,Citation16,Citation23.

We found that, even among asymptomatic patients who were not considered eligible for treatment, CLL can impose a significant psychological burden that results from anxiety of having disease or likelihood of eventual treatment. Nevertheless, treatment with chemotherapy and/or chemoimmunotherapy did not seem to improve HRQoL, and in fact seemed to get worse with multiple lines of therapy. A worsening of HRQoL despite treatment was likely indicative of treatment failure or perhaps reflected intolerable AEs. With standard of care moving away from chemoimmunotherapy, longitudinal studies that analyze the impact of targeted agents on HRQoL are necessary.

Economic burden was assessed in patients with CLL based on disease status (those receiving first-line therapy and those with R/R disease) and treatment regimen received. The main cost drivers were outpatient and hospitalization-related costs, which were incurred mainly as a result of chemotherapy, chemoimmunotherapy, AE management, and disease progressionCitation32,Citation33,Citation40,Citation41. It follows, therefore, that CLL therapies that effectively slow disease progression while minimizing AEs could reduce the economic burden of CLL.

We found only four real-world studies (all conference abstracts) that described the economic impact of targeted agents on CLLCitation36–38,Citation48. Three studies analyzed frontline use of ibrutinib while one study analyzed the economic impact of venetoclax in R/R CLLCitation36–38,Citation48. Continuous treatment with ibrutinib was associated with overall cost savings when compared with chemoimmunotherapyCitation36–38. Cost savings for ibrutinib resulted from lower overall healthcare costs despite higher drug costs than chemoimmunotherapy. However, the ibrutinib studies were characterized by short follow-up times (≈6 months), which may not have captured the full cost of treatment with continuous therapyCitation36–38. Ibrutinib was associated with a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation than chemoimmunotherapy, and ibrutinib-treated patients with cardiac events incurred higher costs of treatment than ibrutinib-treated patients without cardiac eventsCitation36–38. Venetoclax was also associated with lower medical costs than chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy, albeit venetoclax-treated patients were observed over a much shorter period than the chemotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy groupsCitation48. In addition, costs related to AEs were not reportedCitation48. Long-term evidence is needed to fully understand the impact of targeted CLL therapies on healthcare systems. The Platform for Haemotology in EMEA: Data for Real World Analysis (PHEDRA) project, for example, has been developed with the goal of understanding real-world treatment patterns and outcomes related to ibrutinib in a large cohort of patients with CLLCitation51. Similar initiatives should be considered for venetoclax and next-generation BTK inhibitors, such as acalabrutinib.

A majority of economic studies on ibrutinib were studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness and budget impact of ibrutinib versus chemoimmunotherapyCitation52–55. These models reported that while ibrutinib offered significant efficacy advantages over chemoimmunotherapy, such benefits came at a high cost to payers as a result of continuous therapy. Of note, the cost of ibrutinib used in these models was based on list prices, not net prices negotiated between payers and manufacturersCitation56. Net prices are typically not publicly available, resulting in the application of list prices in economic models that overestimate drug costs to payers. Concerns around high treatment costs as a result of continuous BTK inhibitor treatment should nonetheless be addressed in order to ensure patient access to treatment. Value-based pricing, managed-entry agreements, and tendering are examples of tools used by payers to improve treatment affordabilityCitation57. In addition, ongoing clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of finite BTK inhibitor therapy could, if positive, make these agents more affordable by shortening the duration of treatment (NCT03462719 and NCT03836261).

Notable limitations of the literature include a paucity of studies on caregiver burden, incomplete capture of line of therapy especially in HRQoL studies, and, as already mentioned, the impact of targeted agents on HRQoL. We also noted that, of the 11 instruments used to quantify HRQoL, only the FACT-Leu questionnaire has been validated in patients with CLL, and only a further three instruments were designed specifically for patients with cancer. The studies included in the economic burden analysis were typically of short duration and reported only direct costs. Availability of longer-term data, especially on the impact of targeted therapies, as well as data pertaining to indirect costs (such as absenteeism, loss of productivity, transportation-related costs, and costs incurred by caregivers) would be of interest. Finally, as our understanding of the mutational landscape of CLL evolves, and availability of prognostic and predictive biomarkers influences treatment choice, it would be of interest to understand the economic and HRQoL burden of CLL better in patients with high-risk genetic mutations.

Conclusions

Our systematic review expands upon the body of evidence examined in earlier reviews of a similar natureCitation6 and shows that CLL continues to pose a significant burden to patients.

Treatment with chemoimmunotherapy (whether first-line or in R/R disease) was associated with a significant burden due, in part, to treatment failure and the occurrence of AEs. As CLL progresses, and multiple lines of treatment are added, patients experience a further decline in HRQoL, and the economic burden associated with disease management increases. Novel therapies that delay time to progression and offer improved safety could help to mitigate the burden of CLL.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This systematic literature review was sponsored by AstraZeneca.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

CW is an employee of AstraZeneca. SK, SS, and NM are employees of Parexel International. A peer reviewer on this manuscript discloses that their institution has received research funding from AstraZeneca, TG Therapeutics, and BeiGene. The remaining peer reviewers have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

CW was involved in the conception, design, and interpretation of the data. SK, SS, and NM were involved in the design, analysis, and interpretation of the data. All authors revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content, approved the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (74 KB)Acknowledgements

Editorial and writing support was provided by Christina Campbell, Eleanor Finn, and Benjamin Ricca of Parexel International and was funded by AstraZeneca.

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2019. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2019.

- Orphanet Report Series. Prevalence and incidence of rare diseases: bibliographic data. [cited 2019 Sep 18]. Available from: https://www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/Prevalence_of_rare_diseases_by_alphabetical_list.pdf.

- SEER. Cancer Stat Facts: NHL – chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL). [cited 2019 Oct 29]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cllsll.html

- Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111(12):5446–5456.

- Hallek M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2020 update on diagnosis, risk stratification and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(11):1266–1287.

- Frey S, Blankart CR, Stargardt T. Economic burden and quality-of-life effects of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a systematic review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(5):479–498.

- Wang S, Lafeuille MH, Lefebvre P, et al. Economic burden of treatment failure in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(6):1135–1142.

- Chen PH, Ho CL, Lin C, et al. Treatment outcomes of novel targeted agents in relapse/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2019;8(5):737.

- Brown JR, Hallek MJ, Pagel JM. Chemoimmunotherapy versus targeted treatment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: when, how long, how much, and in which combination? Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016; 36:e387–e98.

- Wierda WG, Byrd JC, Abramson JS, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, version 4.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(2):185–217.

- Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic review of interventions. The Cochrane collection. 5.1.0 ed. Oxford: Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

- SIGN. Search filters. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. 2019. [cited 2019 Sep 18]. Available from: https://www.sign.ac.uk/search-filters

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–341.

- Yu H, Zhang H, Yang J, et al. Health utility scores of family caregivers for leukemia patients measured by EQ-5D-3L: a cross-sectional survey in China. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):950.

- Holzner B, Kemmler G, Kopp M, et al. Quality of life of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results of a longitudinal investigation over 1 yr. Eur J Haematol. 2004;72(6):381–389.

- Shanafelt TD, Bowen D, Venkat C, et al. Quality of life in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an international survey of 1482 patients. Br J Haematol. 2007;139(2):255–264.

- Holtzer-Goor KM, Schaafsma MR, Joosten P, et al. Quality of life of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in the Netherlands: results of a longitudinal multicentre study. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(12):2895–2906.

- Buzaglo JS, Miller MF, Karten C, et al. Distress and perceived impact on well-being for low- or intermediate-risk and high-risk patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Blood. 2016;128(22):5970.

- Buzaglo JS, Miller MF, Zaleta AK, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia patient reported outcomes and quality of life: findings from the cancer experience registry. Blood. 2017;130:2122.

- Holzner B, Kemmler G, Sperner-Unterweger B, et al. Quality of life measurement in oncology-a matter of the assessment instrument? Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(18):2349–2356.

- Levin TT, Li Y, Riskind J, et al. Depression, anxiety and quality of life in a chronic lymphocytic leukemia cohort. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(3):251–256.

- Kay NE, Flowers C, Weiss M, et al. Variation in health-related quality of life by line of therapy of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2012;120(21):3926.

- Pashos CL, Flowers CR, Weiss M, et al. Variation in health-related quality of life by ECOG performance status and fatigue among patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2011;118(21):4591.

- Pashos CL, Flowers CR, Weiss M, et al. Variation in health-related quality of life by age among patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Value Health. 2012;15(4):A226.

- Pashos CL, Flowers CR, Weiss M, et al. Association of health-related quality of life with gender in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:S242.

- Pashos CL, Flowers CR, Kay NE, et al. Association of health-related quality of life with gender in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(10):2853–2860.

- McCarrier KP, Bull S, Simacek KF, et al. Online social networks-based qualitative research to identify patient-relevant concepts in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Value Health. 2014;17(3):A196.

- Hahn M, Dietrich S, Hegenbart U, et al. Quality of life (QoL) assessment in patients allografted for poor-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:S422.

- Williams A, Yarosh R, Clark J, et al. Correlates of anxiety and depression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(7_suppl):153.

- Mudondo NP, Parry HM, Damery S, et al. Psychological wellbeing amongst early stage chronic lymphocytic leukaemia patients: a comparative study of primary versus secondary care follow up. Br J Haematol. 2014;165:58.

- Cella D, Jensen SE, Webster K, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in leukemia: the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Leukemia (FACT-Leu) questionnaire. Value Health. 2012;15(8):1051–1058.

- Matasar MJ, DaCosta Byfield S, Blauer-Peterson C, et al. What are the health care costs for chronic lymphocytic leukemia? J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8_suppl):15.

- Gabriel S, Szabo E, Lo-Coco F, et al. Differences in healthcare utilization in CLL patients treated with BR versus FCR. Blood. 2016;128(22):2406.

- Schenkel B, Ellis L, Korrer S, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and health care resource utilization (HRU) among patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) by regimen. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(7_suppl):15.

- Delgado J, Rossi D, Forconi F, et al. Characterising the burden of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in fludarabine-ineligible patients in Spain, Italy, and the United Kingdom (UK): a retrospective observational study. Blood. 2014;124(21):2646.

- Wang S, Emond B, Romdhani H, et al. Front-line ibrutinib treatment is associated with longer time to next treatment, net total cost reduction, and lower healthcare resource utilization compared to chemoimmunotherapy in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2018;132(Supplement 1):2306.

- Nabhan C, Nero D, Hyung Lee C, et al. Cost-effectiveness comparison between ibrutinib, chemotherapy, and chemoimmunotherapy in front-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Blood. 2018;132(Supplement 1):4757.

- Nabhan C, Mato AR, Kish JK, et al. Comparison of costs and health care resource utilization (HRU) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients treated with front-line ibrutinib or chemoimmunotherapy. Blood. 2017;130(Supplement 1):2111.

- DaCosta BS, Blauer-Peterson C, Dawson K, et al. What are the health care utilization and costs associated with patients newly initiating anti-cancer systemic therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia?. J Managed Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24:S29.

- Monberg MJ, Shukla A, Le HV, et al. Economic cost of adverse events per course of therapy with commonly used first-line regimens for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Value Health. 2014;17(3):A79.

- Kabadi SM, Near A, Wada K, et al. Treatment patterns, adverse events, and economic burden in a privately insured population of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the United States. Cancer Med. 2019;8(17):7174–7110.

- Hassan S, Seung SJ, Cheung MC, et al. Examining the medical resource utilization and costs of relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia in Ontario. Curr Oncol. 2017;24(1):e50–e54.

- Hassan S, Seung SJ, Bannon G, et al. Health care resource utilization in the management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in two cancer centres in Ontario. Value Health. 2014;17(3):A79.

- De Cock E, Haiderali A, Wasiak R, et al. The natural history of fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients who fail alemtuzumab or have bulky lymphadenopathy – a European perspective. Value Health. 2011;14(7):A456.

- Parrondo Garcia J, Loscertales Pueyo J, Roldán Acevedo C, et al. Burden of illness of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia that are refractory to fludarabine and alemtuzumab-containing regimens in Spain: Average cost estimation by Monte Carlo simulation. Haematologica. 2014;99:218.

- Reyes C, Gauthier G, Schmerol L, et al. Healthcare cost of Medicare patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2017;102:717.

- Varker H, Meyer N, Gregory S, et al. Treatment patterns, mortality, and costs of care in unfit patients (pts) with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15_suppl):7105.

- Nabhan C, Mato AR, Kish JK, et al. Comparison of costs and health care resource utilization (HRU) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients treated with venetoclax (VEN) or chemotherapy (CT)/chemoimmunotherapy (CIT). Blood. 2018;132(Supplement 1):4758.

- Pfeil AM, Imfeld P, Pettengell R, et al. Trends in incidence and medical resource utilisation in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: insights from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). Ann Hematol. 2015;94(3):421–429.

- Lafeuille MH, Vekeman F, Wang ST, et al. Lifetime costs to Medicare of providing care to patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53(6):1146–1154.

- Garside J, Healy N, Besson H, et al. PHEDRA: using real-world data to analyze treatment patterns and ibrutinib effectiveness in hematological malignancies. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7(1):29–38.

- Chen Q, Jain N, Ayer T, et al. Economic burden of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of oral targeted therapies in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(2):166–174.

- Sinha R, Redekop WK. Cost-effectiveness of ibrutinib compared with obinutuzumab with chlorambucil in untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with comorbidities in the United Kingdom. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18(2):e131–e42.

- Barnes JI, Divi V, Begaye A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of ibrutinib as first-line therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia in older adults without deletion 17p. Blood Adv. 2018;2(15):1946–1956.

- Sorensen SV, Peng S, Dorman E, et al. The cost-effectiveness of ibrutinib in treatment of relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Health Econ Outcome Res. 2016;02(03):121.

- Hernandez I, San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Good CB, et al. Changes in list prices, net prices, and discounts for branded drugs in the US, 2007–2018. JAMA. 2020;323(9):854–862.

- Vogler S, Paris V, Ferrario A, et al. How can pricing and reimbursement policies improve affordable access to medicines? Lessons learned from European countries. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(3):307–321.