Abstract

The term “mixed pain” is increasingly applied for specific clinical scenarios, such as low back pain, cancer pain and postsurgical pain, in which there “is a complex overlap of the different known pain types (nociceptive, neuropathic, nociplastic) in any combination, acting simultaneously and/or concurrently to cause pain in the same body area.” Whether mixed pain is the manifestation of neuropathic and nociceptive mechanisms operating simultaneously or concurrently, or the result of an entirely independent pathophysiological mechanism – distinct from nociceptive, nociplastic and neuropathic pain – is currently unknown. At present, the diagnosis of mixed pain is made based on clinical judgement following detailed history-taking and thorough physical examination, rather than by formal confirmation following explicit screening or diagnostic criteria; this lack of formalized screening or diagnostic tools for mixed pain is problematic for physicians in primary care, who encounter patients with probable mixed pain states in their daily practice. This article outlines a methodical approach to clinical evaluation of patients presenting with acute, subacute or chronic pain, and to possibly identifying those who have mixed pain. The authors propose the use of nine simple key questions, which will provide the practicing clinician a framework for identifying the predominant pain mechanisms operating within the patient. A methodical, fairly rapid, and comprehensive assessment of a patient in chronic pain – particularly one suffering from pain with both nociceptive and neuropathic components – allows validation of their experience of chronic pain as a specific disease and, importantly, allows the institution of targeted treatment.

Introduction

Recently, many chronic pain management–related publications and other activities have focused on the opioid abuse and misuse crisis; however, perhaps insufficient attention has been focused on one of the most important aspects of chronic pain – the actual assessment and diagnostic approach to the person experiencing chronic pain. Within the last decade it has become increasingly clear that “chronic pain does not refer to only one underlying mechanism and cannot be assessed or even treated with a simple one-size-fits-all approach”Citation1. The original International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) terminology with the discrete pathophysiological classification of pain as being either purely nociceptive (pain caused by a damage of non-neural tissue) or purely neuropathic (pain caused by a lesion or disease of neural tissue) was augmented in 2017 with the third mechanistic descriptor, “nociplastic pain”Citation2. The term was included in the IASP Terminology to denote “pain that arises from altered nociception despite no clear evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage causing the activation of peripheral nociceptors or evidence for disease or lesion of the somatosensory system causing the pain”Citation3. Simplified, “nociplastic” is a descriptor for pain that is neither nociceptive nor neuropathic. In the current state of knowledge, “nociceptive” and “neuropathic” have moved beyond hypotheses of mechanism to more concrete bases, while confident demonstration of the altered nociceptive function thought to underlie “nociplastic” awaits further elucidation. However, just as the IASP taxonomy insists that “neuropathic” is a descriptor and not a diagnosis per se, so that same constraint applies to “nociplastic.” The term is now being utilized to describe conditions such as fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome type 1, and irritable bowel syndrome but it should not be used for all conditions “that cannot be better accounted for by another chronic pain condition.” In the absence of validated clinical criteria and pathophysiological correlations for identifying nociplastic pain, such a claim is premature.

And what about an overlap of the different known pain types in any combination? In particular, how should one denote a combination of nociceptive and neuropathic pain in clinical entities such as neck pain or low back pain with a neuropathic component, lumbar spinal stenosis, sciatica, cancer pain, osteoarthritis pain, and chronic postsurgical pain? For these specific clinical scenarios, the term “mixed pain” is increasingly recognized and accepted by pain cliniciansCitation1. Developed in the context of an absence of a formal IASP definition, a recently published attempt at a first definition is: “Mixed pain is a complex overlap of the different known pain types (nociceptive, neuropathic, nociplastic) in any combination, acting simultaneously and/or concurrently to cause pain in the same body area. Either mechanism may be more clinically predominant at any point of time. Mixed pain can be acute or chronic”Citation1.

Whether mixed pain is the manifestation of neuropathic and nociceptive mechanisms operating simultaneously or concurrently, or the result of an entirely independent pathophysiological mechanism – distinct from nociceptive, nociplastic and neuropathic pain – is currently unknown. However, that the mechanisms of mixed pain cannot be characterized as yet serves as an impediment to further research on mixed pain screening and diagnostic tools, as well as on specific treatments targeting mixed pain statesCitation4. At present, the diagnosis of mixed pain is made based on clinical judgement following detailed history-taking and thorough physical examination, rather than by formal confirmation following explicit screening or diagnostic criteria.

The lack of formalized screening or diagnostic tools for mixed pain is problematic for physicians in primary care, who encounter patients with probable mixed pain states in their daily practice. The aim of this article is to outline a methodical approach to clinical evaluation of patients presenting with acute, subacute or chronic pain, and to possibly identifying those who have mixed pain.

Nine questions: a framework for history-taking in suspected cases of acute, subacute or chronic mixed pain states

How should a primary care physician approach a pain patient? We describe as an example the diagnostic work-up in a short case scenario of a “typical” mixed pain patient presenting with chronic low back pain (). Despite the technological wizardry inherent in modern medicine, the most difficult diagnostic puzzles are often unraveled by a carefully conducted, patient-centered interview. In clinical practice, the interview is a collaborative effort between physician and patient and is most effective if tailored to the patient's individual cognitive and communication style.

Table 1. Patient case details.

Although we all agree that there is no “golden question” that reveals exactly the underlying pain type, answering the question, “what could be among the several structures potentially involved in this specific chronic low back pain patient” is already a key factor for successful management, since a diagnosis not based on the underlying pain type(s) can lead to therapeutic mistakes. Hence, there are at least some “essential key questions” which can provide the practicing clinician a conceptual framework and may thus serve as a basic structure for the medical interview to identify the predominant pain mechanisms operating within the individual patient.

Therefore, we propose the use of nine simple key questions, which will provide the practicing clinician a framework for identifying the predominant pain mechanisms operating within the patient. Asking questions of a patient will, in many cases, reveal their diagnosis; however, it is crucial that one asks the right questions, and understands and translates the answers appropriately.

The rationale for each question is described below, with a hypothetical answer to that question serving as a jumping-off point for discussion. It is clear that many more questions can be raised and, beyond doubt, based on the individual case, other issues might be of more importance. However, reading in between the answer lines of these questions might guide the clinician to find important puzzle stones that complement an essential detailed physical examination and, together with answers to a pain questionnaire, lead to a clearer diagnostic picture. Given that some patients become quite talkative during the examination as they feel more at ease than when sitting face to face during the interview, it might be the perfect time to ask these questions while running the bedside tests. Importantly, if the patient is experiencing more than one type of pain, the clinician should consider evaluating each pain separately using these questions.

Question 1. Where exactly do you feel your pain? please mark the painful areas in this pain drawing

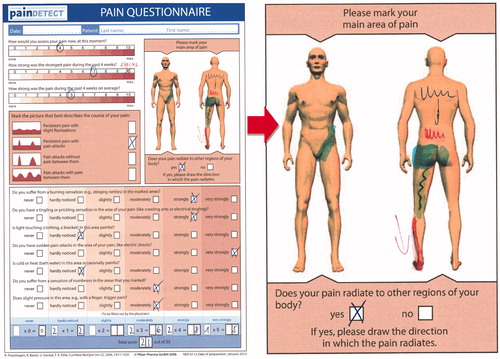

Patient’s answer: I feel it in the whole lower back, and it often radiates into the buttocks and down the back of my left thigh to the back of the knee. Over the past couple of weeks, I have been feeling it radiate down my left leg and foot, like an electric shock. Here is my pain drawing. ()

Figure 1. Pain diagram from the patient’s painDETECT questionnaire (enlarged right side). Final painDETECT Score: 20, indicating that a neuropathic pain component is likely (>90%).

Localization of painful areas is a cornerstone of pain diagnosis. While the patient’s verbal description of the location of pain is important, use of a pain drawing – a schematic of the human body on which the patient indicates the painful area – allows rapid visualization of these painful areas, facilitating the diagnostic processCitation5. painDETECT, a widely used, validated screening questionnaire for neuropathic pain, contains a pain drawing as a key componentCitation6. Pain in more than one body area, especially following a clear dermatomal pattern or neuroanatomical plausible distribution, is suggestive of a neuropathic component. Different neuropathic pain syndromes are characterized by specific pain localizations (e.g. low back pain with radiation down the lower limb for lumbar radiculopathy, “glove and stocking” pattern for painful diabetic polyneuropathy, single-dermatome pain for postherpetic neuralgia). A damaged nerve not infrequently can cause symptoms in many locations “downstream” from the damage, so that it appears more as a widespread type of pain. In contrast, pain not localized in a neuroanatomical distribution is likely associated with a nociceptive or nociplastic component.

Question 2. What words would you use to describe your pain?

Patient’s answer: I feel a constant sensation of a deep intense pressure in the buttock, like an ongoing tense cramp, and diffuse burning in the lower back. That’s what bothers me the most. Over the past few weeks my left leg feels occasionally hot and cold at once, accompanied by a feeling of numbness, as if it would fall asleep. Then suddenly, without any warning, I feel a stabbing, sometimes a shooting, electric shock down my leg. On other days it feels more like a hundred crawling ants on my foot, or like pins and needles.

Pain is essentially a subjective phenomenon described with patient-specific symptoms and expressed with a certain intensity. Therefore, it is crucial that patients describe their symptoms in as much detail as possible. Attentive listening is often more useful than jumping to direct examination, particularly when pain fluctuates and there is little in the way of objective signs.

Of note, although the quality of pain may be unique to each person, there are words that are commonly used by people experiencing a specific type of pain. Careful consideration of these pain descriptors enables the clinician to distinguish neuropathic pain from nociceptive pain. Burning, stabbing, shooting, prickling, tingling, numbness, pain in a numb area, or a pins-and-needles feeling, are descriptors commonly used by people experiencing a neuropathic type of pain. In addition, they often report spontaneous pain, pain that occurs without a trigger, evoked pain, or pain that is caused by events that are typically not painful (allodynia). Autonomic signs (e.g. cold or hot limbs) may indicate a direct consequence of a nerve injury, or a spinal/supraspinal reflex to the nociceptive input. In contrast, the descriptors aching, deep, and dull are often used to describe a nociceptive pain componentCitation7. More recently, the descriptors squeezing, internal pressure, and feeling of tense muscles have been shown to be typical nociceptive-like symptomsCitation8.

The distinction between neuropathic and nociceptive pain is not always straightforward, and even in patients categorized as having neuropathic pain, a nociceptive pain component can be present. The patient’s use of a combination of neuropathic pain descriptors and nociceptive pain descriptors points to a possible diagnosis of mixed pain.

Question 3. How long have you been experiencing your pain?

Patient’s answer: For the past 7 months I have been dealing with this pain in my lower back; for the past 4 weeks, it has been radiating into my left leg and foot.

Pain and related symptoms and signs may vary in relation to the temporal evolution of the painful disease, and to the comorbid psychological problems of the patient. In ICD-11, chronic pain is defined as persistent or recurrent pain lasting longer than 3 monthsCitation9. This new definition has the advantage of being clear and operationalized, thereby advancing the recognition of chronic pain as a specific health condition. Whether pain can become chronic at an earlier stage (sometimes called “subacute,” denoting pain that has been present for at least 6 weeks but less than 3 monthsCitation10) is a research question and not conclusively answered. Moreover, the presence of chronic pain should prompt the clinician to consider mixed pain at least as a differential diagnosis, as acute pain is typically associated with nociceptive pain and the majority of neuropathic pain conditions are usually chronic in nature. However, it must be kept in mind that all neuropathic pains obviously must have had a history of an acute phase.

Question 4. On a scale of 0–10, how intense is your pain at rest and during movement?

Patient’s answer: At rest it feels like maximum 5, minimum 3. During movement it is worse, so I would say maximum 7, minimum 3. But the electric shocks down to the left foot which I have very often now, can feel like 10. They are excruciating!

Use of an 11-point Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) – from 0 to indicate “no pain,” to 10 to indicate “pain as bad as it could be” – is often preferred due to its simplicity in administration, cross-cultural validityCitation11 and reliability. It should be noted, however, that pain intensity is a poor indicator of back pain ominousness. Some life-threatening causes of back pain (e.g. tumor) cause minimal levels of pain, especially in the early stages; conversely, many relatively benign etiologies (e.g. muscle cramps) can cause excruciating pain. Nevertheless, data from large cohorts of patients with chronic pain indicate that patients suffering from pain with neuropathic characteristics typically report higher pain scores at rest and at movement than those with nociceptive characteristicsCitation12–14. Moreover, neuropathic symptoms have been shown to strongly correlate with duration of daily pain;Citation15 it is hypothesized that neuropathic pain is not always recognized as such by primary care physicians, so that therapy is instituted that is aiming for nociceptive rather than neuropathic components, leading to insufficient pain reduction. A high index of suspicion for mixed pain should be maintained for any chronic pain patient reporting very high and long-lasting pain scores, which might fluctuate throughout the day.

Question 5. Do you feel pain constantly, more on movement or more at rest?

Patient’s answer: I feel pain in both instances, but it is probably a bit worse with movement. When I am sitting at my desk in front of my PC, I need to get up after around 15 min because it’s getting too painful and I can’t sit anymore. When I am driving, I have to stop the car every so often so I can get out of a sitting position and stretch my legs. On the other hand, the pain is exacerbated by prolonged standing and walking, particularly walking at a fast pace or for more than 30 min. Sleeping is a problem too – sometimes my left leg falls asleep and then, suddenly, I feel an electric shock down my foot. In the morning when I get out of bed, I feel completely stiff, as if my body were breaking into pieces in the first half-hour – this is usually the worst time of the day.

In the context of low back pain, natural degeneration of facets from normal aging leads to swelling, inflammation and pain. Pain associated with a facet joint syndrome is often called “referred pain” because symptoms do not follow a specific nerve root pattern. Local tissue pathology and inflammation can cause serious painful symptoms and disability, which are hallmarks of nociceptive pain. Inflamed facets can cause a powerful muscle spasm which can become continuous, fatiguing the involved back muscles which, in turn, repeats the cycle. Bursts of movement can aggravate symptoms. Nevertheless, each joint has a rich supply of tiny nerve fibres that provide a painful stimulus when they are injured or irritated by inflammatory mediators, which can lead to a local neuropathic type of pain.

Shooting pain that radiates like an electric shock from the lumbar spine to the buttocks and onwards to the back of the thigh and calf into the foot is the hallmark of sciaticaCitation16,Citation17. Sciatica most commonly occurs when a herniated disc, bone spur on the spine, synovial cysts or narrowing of the spine (spinal stenosis) compresses part of a spinal nerve, leading to pain and oftentimes numbness in the affected leg. Lumbar disc herniation is one of the most common causes of neuropathic lower back pain associated with shooting leg pain. Sciatica may occur spontaneously at rest, and prolonged sitting can aggravate symptoms (riding a car, sitting at a desk). Conversely, pain may be aggravated by coughing or sneezing, or movements such as bending, lifting and twisting.

Question 6. Is your pain related to any identifiable cause? How did it start and develop?

Patient’s answer: I think it may have developed because of my job, which entails 8 to 10 h of sitting a day. Also, I think it may be because I haven’t engaged in sports for over two years now – no more running, no more gym, no more tennis. My pain began gradually, then it progressively became worse over a few short months. I think the level of pain has stabilized somewhat, but it still affects my life quite a bit. The shooting pain down my legs, like electric shocks, is something that started spontaneously.

Nociceptive pain is usually acute and develops in response to a specific situation. It typically changes with movement, position and load, and tends to get better as soon as the affected body part heals. However, untreated nociceptive pain can become chronic; in this patient, facet-joint degenerative osteoarthritis, coupled with intervertebral disc degeneration, likely may have spurred the development of acute inflammatory pain that has then become chronic.

Neuropathic pain arises from damage to the central or peripheral nervous system. In addition, repetitive injury to tissue, muscles, or joints can cause lasting damage to nerves. While the injury may heal, the damage to, and consequent effect on, the nervous system may not. As a result, patients may experience persistent neuropathic pain many years after the injury and, thus, are unable to link the injury to the current pain. Importantly, neuropathic pain can be a symptom or complication of various diseases and conditions (e.g. diabetes, varicella zoster infection, surgery); however, patients are largely unaware of the link between these conditions and their pain. Mixed pain can be both acute and chronic.

In this patient, degenerative processes led primarily to an acute nociceptive type of pain, referred distally to the buttock and the trochanteric region, the groin and the thighs, ending above the knee, without neurological deficits (pseudo-radicular). Over time, this pain became overlapped by neuropathic symptoms which are often due to a nerve root impingement (in this patient, by a large synovial facet cyst), which causes radiculopathy. A patient’s pain sensation may change over time. The symptomatology here reflects a typical picture of a chronic mixed pain state.

Question 7. What have you done to treat your pain?

Patient’s answer: I started with ibuprofen and that was good for the first few weeks, but then I developed stomach pain and some acid reflux so I didn’t feel that I could take it any longer. Then I was prescribed celecoxib by my orthopaedic surgeon, which was a bit helpful and better for my digestion, but I stopped taking it when my prescription ran out. I did some physiotherapy, which was not helpful at all, then I got a steroid injection which relieved the pain, but only for two weeks. My doctor offered me lately tramadol, which I don’t want to take regularly – I am afraid of getting addicted so I only take it as needed, when I really need to function. It helps relieve my pain, although I feel a bit sick within the first few hours. As an alternative, he prescribed pregabalin. I only take it at night and I realize that I can sleep better, and the electric shocks are much less frequent now. However, it makes me a bit dizzy so I don’t take it when I work during the day.

Response to medication may offer some clues to the underlying pain type. Nociceptive pain states are responsive to over-the-counter analgesics and non-opioid prescription drugs, including nonspecific nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), paracetamol, muscle relaxants and COX2 inhibitors. Osteoarthritis of the spine involving the facet joints – a typical nociceptive, often inflammatory pain state – is responsive to injection of corticosteroids and local anaesthetics. Intra-articular, periarticular and medial branch infiltrations can be helpful for diagnosis, however, most guidelines do not recommend these invasive procedures for therapeutic management of chronic low back painCitation18. Pain reduction with alpha-2-delta ligands, tricyclic antidepressants, and serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors suggests pain with a neuropathic componentCitation19; of note, based on clinical experience, most pain physicians will also use drugs from these therapeutic classes for the treatment of mixed pain conditions. Classical opioids and tramadol are effective for both acute and chronic pain of either nociceptive or neuropathic originCitation20–22, hence, response to these agents is usually not helpful in discriminating between the two.

Question 8. Has your pain caused you psychological distress?

Patient’s answer: For the past several weeks, I have not been sleeping well. There are now more sick days when I really can’t work. Turning up to work under the influence of these drugs I’ve been given is impossible and so I’ve started thinking all these negative thoughts – that I’m damaged for the rest of my life, that I will probably end up with a disability pension. They are in my head 24/7. Occasionally I will think, I will get better someday, but these instances are rare.

The degree to which neuropathic and non-neuropathic pain conditions differ with respect to associated comorbidities is still largely unexplored. and it is impossible to correlate pain and comorbidity scores with the underlying pain type accordingly.

However, there is growing evidence to suggest that patients with chronic neuropathic pain experience worse health-related quality of life (QoL); greater psychological distress with higher levels of depression, anxiety and catastrophizing; increased interference with sleep; and loss of more workdays and productivity, compared with patients with chronic pain without neuropathic characteristicsCitation6,Citation12,Citation23–27. Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that mixed pain is associated with impairments in overall QoL, and that mixed pain is associated with lower physical and mental QoL than neuropathic pain aloneCitation28.

Question 9. Have you experienced any other symptoms or changes which have worried you?

Patient’s answer: I don’t know if this is important but I feel constant fatigue. At night I am tired, however, I hardly get any sleep, and I feel really groggy during the day. I have lost some weight but I think this is due to intermittent diarrhoea, which I’ve experienced over the past 2 months – I think this has something to do with my pain medication. When I was taking ibuprofen, I had a lot of acid reflux and abdominal pain – this has resolved.

The primary purpose of this question is to identify any red flags – signs and symptoms that may indicate a serious or life-threatening pathology. Numerous published guidelines support the use of red-flag questions to screen for serious pathology in patients with low back pain (i.e. malignancy, fracture, cauda equina syndrome, infection).

Secondarily, this question is aimed at eliciting further clues to the nature of the patient’s pain condition. A report of motor weakness, sensory deficits, saddle anaesthesia or bladder dysfunction indicates nervous system involvement, which suggests a neuropathic component; a report of symptoms that indicate acute or chronic inflammation points to a nociceptive component. Importantly, chronic inflammation presents with a varied symptomatology, including constant fatigue and insomnia, mouth sores, rashes, gastrointestinal complications (constipation, diarrhoea, acid reflux, abdominal pain), weight gain or loss, frequent infections, and mood disorders (depression, anxiety).

The clinician should keep in mind that a negative response to one or two red-flag questions does not meaningfully decrease the likelihood of a serious diseaseCitation29 and that none of these questions provides definitive diagnostic information on a particular type of pain.

summarizes the replies to key questions that would direct the clinician to consideration of nociceptive pain versus neuropathic pain versus mixed pain. It also includes a summary of the responses of our patient – the totality of which allows us to identify his pathology as an chronic mixed pain state.

Table 2. Answers to key questions that may help identify mixed pain.

General guidance on physical examination and diagnostics

A comprehensive diagnostic should include a general, symptom-directed and thorough neurological physical examination. Particularly when advanced degenerative changes are found in the lumbar spine, clinically relevant differential diagnoses must be ruled out as they can cause overlapping symptoms. A psychological evaluation is mandatory as a psychopathological component may turn out to be a relevant cause of the patient’s symptoms – this is particularly true for patients with neuropathic pain and mixed pain of prolonged duration.

The use of questionnaires for assessment of the location and type of the pain syndrome, as well as determination of important comorbid disorders, is recommended. The authors propose the use of the painDETECT questionnaire (or another validated neuropathic pain screening tool, such as the self-reported Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs [s-LANSS] or Douleur Neuropathique en 4 Questions [DN4]), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (a patient-reported instrument for screening, diagnosing and measuring the severity of depression) and the Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale (a patient-reported, non-disease-specific instrument for evaluating sleep outcomes) as brief and useful screening tools in the assessment of patients with chronic (low back) painCitation6,Citation30–33.

Laboratory tests can help rule out inflammatory aetiologies and can also provide evidence of an acute or chronic metabolic disturbance as the cause of symptoms.

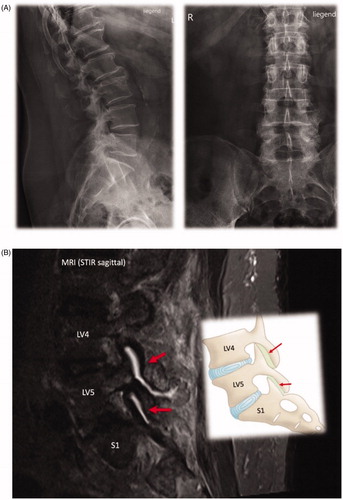

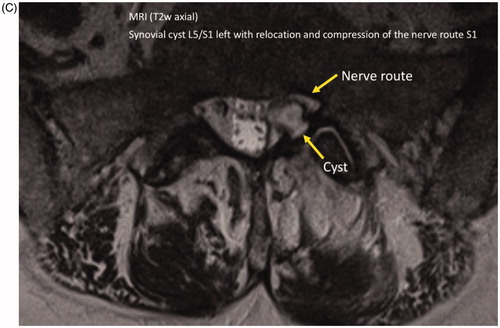

Imaging studies are important adjuncts in the diagnostic evaluation of acute and chronic pain conditions. However, they should only be performed if they are needed for treatment-planning or if they might lead to changes in a patient’s treatment. Conventional (plain) X-ray methods can predominantly determine pathological changes in the bone tissue itself. Magnetic resonance imaging is the standard procedure for demonstration of the degree of pathological changes in the soft tissue structures of the spinal canal and intervertebral discs. However, morphometric descriptions are defined by purely radiological criteria and lack any clinical correlation in themselves. Thus, they convey no more than auxiliary information to be considered in diagnosis and treatment planning.

and summarize the physical, laboratory and imaging findings of the patient described in .

Figure 2. Imaging findings. (A) Multisegmental osteochondrosis with anterior spondylosis of the thoracic 11/12 and lumbar 1/2/3. Caudally emphasized facet joint arthrosis. (B) Spondylarthrosis L3/4/5 and S1 (hypertrophic, destructive and activated as L4/5). (C) Synovial cyst L5/S1 left with relocation and compression of the nerve route S1 left.

Table 3. Patient case details (continued).

Conclusion

As depicted in , in our patient eight of the nine questions point to the direction of an underlying chronic mixed pain state. The patient’s problems started with a pseudo-radicular nociceptive type of pain most likely due to degenerative multisegmental osteochondrosis and a concomitant facet joint syndrome. Over time, a nerve root impingement by a large synovial facet cyst overlapped the nociceptive pain with neuropathic symptoms of radiculopathy.

Patients with pain problems which are yet not well understood, e.g. nociplastic pain or mixed pain, are still at a high risk of hearing that their pain is not real or “all in the head.” A methodical, fairly rapid, comprehensive assessment of a patient in chronic pain – particularly one suffering from pain with both nociceptive and neuropathic components – allows validation of their experience of chronic pain as a specific disease and, importantly, allows the institution of targeted treatment. For our patient, it is crucial to consider early treatment with a combination of agents targeting nociceptive and neuropathic pain mechanisms (multimodal analgesia), delivered as part of a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach; an inadequate response to early combination treatment will necessitate referral to and management by a pain specialist.

As currently the diagnosis of mixed pain is made based on clinical judgement following detailed history-taking and thorough physical examination, rather than by formal confirmation following explicit screening or diagnostic criteria (which are, as yet, not available), these nine questions can be used as a golden thread to approach this often very complex situation and to manage it accordingly. Since we would all likely agree that accurate assessment leads to accurate diagnosis, which in many medical conditions (such as cancers and infectious diseases) leads to better treatment, let us also agree that such an approach would benefit the treatment of people suffering from acute or chronic mixed pain. Thus, the authors advise: ask your patients and they may tell you in many cases their diagnosis. But always keep in mind, the right questions can make a difference!

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Medical writing and editing services were sponsored by P&G Health Germany GmbH.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

RF reports consultancy and speaker fees in the past 2 years from AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Grünenthal, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Pfizer, P&G Health and Scilex Pharmaceuticals, outside of the submitted work. RR reports consultancy and speaker fees in the past 2 years from Gador Argentina, Merck Argentina, Pfizer, P&G Health and Teva Argentina. CA reports consultancy and speaker fees in the past 2 years from Allergan, Daiichi Sankyo, Grunenthal, Pfizer, Flowonix, Vertex, Amgen, Novartis, Teva, Eli Lilly, Kaleo, and Theranica.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design of the manuscript. RF was responsible for drafting of the paper; all authors participated in revising it critically for intellectual content; and all authors gave the final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Harold Arevalo Parada, Dr Juythel Chen, Professor Freddy Javier Fernandez Villacorta, Professor Mariano Fernandez Fairen, Dr Kok Yuen Ho, Professor Argelia Lara-Solares, Dr Camilo Partezani Helito, Dr Maria Dolma Santos and especially Branislava Obradovic Zdero for participating in informal discussions, the outputs of which served as framework for the content of this manuscript. The authors also thank Dr Jose Miguel (Awi) Curameng of MIMS (Hong Kong) Limited for providing medical writing and editing support for this manuscript.

References

- Freynhagen R, Parada HA, Calderon-Ospina CA, et al. Current understanding of the mixed pain concept: a brief narrative review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(6):1011–1018.

- IASP Council Adopts Task Force Recommendation for Third Mechanistic Descriptor of Pain [Internet]. Washington (DC): International Association for the Study of Pain; 2018.

- IASP Terminology [Internet]. Washington (DC): International Association for the Study of Pain; 2018.

- Morlion B. Pharmacotherapy of low back pain: targeting nociceptive and neuropathic pain components. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(1):11–33.

- Hüllemann P, Keller T, Kabelitz M, et al. Pain drawings improve subgrouping of low back pain patients. Pain Pract. 2017;17(3):293–304.

- Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, et al. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(10):1911–1920.

- Marchettini P, Lacerenza M, Mauri E, et al. Painful peripheral neuropathies. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2006;4(3):175–181.

- Tolle TR, Baron R, de Bock E, et al. painPREDICT: first interim data from the development of a new patient-reported pain questionnaire to predict treatment response using sensory symptom profiles. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(7):1177–1185.

- Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain. 2019;160(1):19–27.

- van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions. Spine. 1997;22(18):2128–2156.

- Booker S, Herr K. The state-of-“cultural validity” of self-report pain assessment tools in diverse older adults. Pain Med. 2015;16(2):232–239.

- Bouhassira D, Lantéri-Minet M, Attal N, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain. 2008;136(3):380–387.

- Freynhagen R, Tölle TR, Gockel U, et al. The painDETECT project – far more than a screening tool on neuropathic pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(6):1033–1057.

- Spahr N, Hodkinson D, Jolly K, et al. Distinguishing between nociceptive and neuropathic components in chronic low back pain using behavioural evaluation and sensory examination. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2017;27:40–48.

- Berthelot JM, Biha N, Darrieutort-Laffite C, et al. Are painDETECT Scores in musculoskeletal disorders associated with duration of daily pain and time elapsed since current pain onset? Pain Rep. 2019;4(3):e739

- Jensen RK, Kongsted A, Kjaer P, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. BMJ. 2019;367:l6273.

- Ropper AH, Zafonte RD. Sciatica. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(13):1240–1248.

- Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, et al. Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(S2):S192–S300.

- Finnerup N, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(2):162–173.

- Freynhagen R, Geisslinger G, Schug SA. Opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. BMJ. 2013;346:f2937.

- Busse JW, Wang L, Kamaleldin M, et al. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;320(23):2448–2460.

- Hegmann KT, Weiss MS, Bowden K, et al. ACOEM practice guidelines: opioids for treatment of acute, subacute, chronic, and postoperative pain. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(12):e143–e159.

- Argoff CE. The coexistence of neuropathic pain, sleep, and psychiatric disorders: a novel treatment approach. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(1):15–22.

- Freynhagen R, Baron R. The evaluation of neuropathic components in low back pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(3):185–190.

- Mahn F, Hüllemann P, Gockel U, et al. Sensory symptom profiles and co-morbidities in painful radiculopathy. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e18018.

- Torta R, Ieraci V, Zizzi F. A review of the emotional aspects of neuropathic pain: from comorbidity to co-pathogenesis. Pain Ther. 2017;6(Suppl 1):11–17.

- Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Thompson T, et al. Pain and severe sleep disturbance in the general population: primary data and meta-analysis from 240,820 people across 45 low- and middle-income countries. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018;53:52–58.

- Gálvez R, Marsal C, Vidal J, et al. Cross-sectional evaluation of patient functioning and health-related quality of life in patients with neuropathic pain under standard care conditions. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(3):244–255.

- Verhagen AP, Downie A, Popal N. Red flags presented in current low back pain guidelines: a review. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(9):2788–2802.

- Bennett MI, Smith BH, Torrance N, et al. The S-LANSS score for identifying pain of predominantly neuropathic origin: validation for use in clinical and postal research. J Pain. 2005;6(3):149–158.

- Bouhassira D, Attal N, Alchaar HA, et al. Comparison of pain syndromes associated with nervous or somatic lesions and development of a new neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire (DN4). Pain. 2005;114(1–2):29–36.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613.

- Hays RD, Stewart AL. Sleep measures. In: Stewart AL, Ware JEJ, editor. Measuring functioning and well-being; the medical outcomes study approach Duke edition. Durham: Duke University Press; 1992. p. 235–259.