Abstract

Aims

To compare adherence, rates of subsequent schizophrenia-related relapses, healthcare resource utilization, and healthcare costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia who initiated once-monthly paliperidone palmitate (PP1M) versus a new oral atypical antipsychotic (OAA) following a recent schizophrenia-related relapse.

Methods

Six-state Medicaid data (01/2009–03/2018) were used to identify adults with schizophrenia initiated on PP1M or OAA (index date) within 30 days following a schizophrenia-related relapse (defined as a schizophrenia-related inpatient or emergency room visit). Patients were required to have 12 months of continuous eligibility before (baseline) and after (observation) the index date. Differences in baseline characteristics between PP1M and OAA patients were accounted for using 1:3 matching.

Results

After matching, characteristics were well-balanced between PP1M (N=208, mean age=39 years, 35.6% female) and OAA patients (N=624, mean age=40 years, 34.6% female). During the 12-month observation period, the mean proportion of days covered for the index medication was 41.2% in the PP1M cohort and 34.7% in the OAA cohort (p=.008). Relative to the OAA cohort, PP1M patients were 33% (p=.013) less likely to have a subsequent relapse and had 29% (p=.004) fewer all-cause inpatient admissions per-patient-per-year (PPPY). Consequently, a significant mean reduction of $6273 in medical costs PPPY (p=.028) was observed, which fully offset the $4770 (p<.001) increase in pharmacy costs PPPY and resulted in a numerical but not statistically significant, decrease in total healthcare costs of $1503 PPPY (p=.621) relative to OAA patients.

Conclusions

Among patients with a recent schizophrenia-related relapse, PP1M was associated with a lower risk of subsequent relapse while remaining a cost neutral therapeutic option compared to OAAs.

Background

Schizophrenia is a chronic, highly incapacitating psychiatric disorder that typically manifests during young adulthoodCitation1,Citation2. The disease is characterized by a variety of psychopathological symptoms, such as delusions, hallucinations, and disorganization, that result in impairments in occupational and social functioningCitation1,Citation2. Schizophrenia is estimated to affect between 0.25 and 0.64% of the United States (US) populationCitation3.

One of the most distressing and costly outcomes associated with schizophrenia is symptomatic relapse. As many as 80% of patients who initially respond to antipsychotic (AP) treatment experience a relapse within 5 yearsCitation4. In addition to their serious, near-immediate effects (e.g. self-harm and loss of employment)Citation5,Citation6, there is evidence that relapses may lead to AP treatment resistance, thereby complicating disease managementCitation7. Furthermore, patients who relapse exhibit 2-4 times higher healthcare costs than those who never relapseCitation8,Citation9. Therefore, preventing relapses is of crucial importance in the clinical management of schizophrenia.

AP therapy is the cornerstone of schizophrenia treatmentCitation2 and has proven efficacious in preventing relapsesCitation10. However, the real-world effectiveness of oral atypical APs (OAAs) is hindered by low rates of adherenceCitation11–14. The American Psychiatric Association guidelines recommend the use of long-acting injectables (LAIs) in patients with recurrent relapses related to non-adherenceCitation2 and the Florida Medicaid guidelines recommend LAIs as initial treatment after trial of an OAA in monotherapy or among patients who are non-adherent or refractory to initial treatmentCitation15. Once-monthly paliperidone palmitate (PP1M) is an LAI approved for the treatment of adult patients with schizophreniaCitation16. Numerous real-world studies have shown that PP1M treatment is associated with improved adherence and reduced rates of hospitalizations relative to OAA treatmentCitation13,Citation14,Citation17–24, while poor adherence to OAAs has been shown to increase healthcare costs associated with schizophrenia managementCitation25,Citation26. In contrast, PP1M has been invariably associated with lower medical costs that fully offset higher pharmacy costs relative to OAAsCitation14,Citation17–20.

Patients who experience a recent relapse may be at particularly higher risk of having a subsequent relapse. Previous clinical studies have shown that PP1M was associated with a reduction in hospitalizations, longer time to treatment failure, and longer time to relapse relative to OAAsCitation22–24. Additionally, two previous real-world studies evaluating the occurrence of relapses/rehospitalizations among patients with a recent hospitalization initiated on PP1M versus OAA found that PP1M was associated with a reduction in relapses/rehospitalizations and costsCitation20,Citation21. However, both studies comprised patients covered by multiple types of health plans; hence, findings may not be generalized to patients with other types of plans, such as Medicaid. Therefore, the present study sought to compare adherence, rates of subsequent schizophrenia-related relapses, healthcare resource utilization (HRU), and healthcare costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia who initiated PP1M versus a new OAA following a recent schizophrenia-related relapse.

Methods

Elements pertaining to the methods of the study including the data source, study design, selection criteria, study measures, and statistical analysis were determined during the protocol phase, prior to conducting the analysis.

Data source

Medicaid data from Iowa (1998Q1-2017Q1), Kansas (2001Q1-2018Q1), Mississippi (2006Q1-2018Q1), Missouri (1997Q1-2018Q1), New Jersey (1997Q1-2014Q1), and Wisconsin (2004Q1-2013Q4) were used. The database includes information on enrollment eligibility, physician visits, hospitalizations, long-term care services, prescription drugs, and other services reimbursed by Medicaid. Medical claims available in the databases contain diagnosis and procedure information. Prescription drug claims contain information on the name, dosage, formulation, and days of supply of the medication. Cost information is pre-rebate and represents the actual amount paid by Medicaid for services rendered. Claims reimbursed by Medicare for patients with dual Medicare/Medicaid eligibility are available in the database; however, amounts paid by Medicare are not captured. Data were de-identified and comply with the patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Study design

A retrospective longitudinal cohort design was used. The first observed schizophrenia-related relapse (defined as having an inpatient or emergency room [ER] visit with a diagnosis for schizophrenia) followed by the initiation of PP1M (PP1M cohort) or an OAA (OAA cohort) ≤30 days post-discharge was used for cohort entry. The index date was defined as the date of initiation of PP1M or OAA within 30 days post-discharge from a schizophrenia-related relapse. Patients had to be newly initiated on their index treatment (i.e. no claim for the index treatment in the 12 months prior to the index date). Baseline characteristics were evaluated during the 12 months prior to the index date (baseline period). The follow-up period was defined as the 12-month period following the index date.

Selection criteria

Patients were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) ≥2 diagnoses for schizophrenia (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision: 295.XX; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision: F20.XX, F21, F25.X) during the period of continuous Medicaid eligibility, including ≥1 diagnosis during the baseline period; (2) ≥1 schizophrenia-related relapse; (3) initiation of PP1M or an OAA on or after January 1, 2010 and ≤30 days following discharge from a schizophrenia-related relapse; (4) ≥18 years of age on the index date; (5) ≥12 months of continuous Medicaid eligibility prior to and after the index date.

Patients were excluded if they had ≥1 claim for an LAI during the baseline period and ≥1 claim for clozapine on or prior to the index date. To capture the initiation of the specific OAA used on the index date, patients in the OAA cohort were excluded if they had ≥1 claim for the index OAA during the baseline period.

Study measures

Adherence was measured during follow-up using the proportion of days covered (PDC), which was defined as the sum of non-overlapping days of supply of the index medication divided by the duration of the observation period (i.e. 12 months). The proportion of patients with a subsequent schizophrenia-related relapse and the number of subsequent schizophrenia-related relapses were evaluated during follow-up. A relapse was defined as the occurrence of an inpatient admission or ER visit with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

All-cause HRU was assessed and included inpatient, ER, outpatient, and other services (which included long-term care admissions, mental-health institute admissions, one-day mental-health institute outpatient visits, home care, and other services). Total all-cause healthcare costs were assessed and broken down into pharmacy and medical costs. Medical costs were further broken down into inpatient, ER, outpatient, and other service costs. Study outcomes were reported per-patient-per-year (PPPY) during the 12-month follow-up period, and costs were adjusted to 2018 US dollars using the medical care component of the US Consumer Price Index.

Statistical analysis

Patients in the PP1M cohort were matched 1:3 to patients in the OAA cohort based on exact matching factors (i.e. 1, 2, 3, and ≥4 prior relapses) and propensity scores obtained from a logistic regression that included the following baseline covariates: age, sex, race, state, year of the index date, type of healthcare plan, Quan-Charlson Comorbidity Index (Quan-CCI) score, type of schizophrenia disorder, prevalent comorbidities (i.e. substance-related and addictive disorders, depression, hypertension, and diabetes), baseline treatment patterns (i.e. typical oral AP use, OAA use, number of AP claims, antidepressant use, anxiolytic use and mood stabilizer use), and baseline HRU (i.e. number of inpatient admissions and having ≥1 mental-health institute admission).

Comparison of baseline characteristics between matched study cohorts were performed using standardized differences. Characteristics with standardized differences <10% were considered balancedCitation27. HRU binary variables were compared during the observation period between matched cohorts using odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values obtained from logistic regressions. HRU count variables were compared during the observation period between matched cohorts using rate ratios obtained from Poisson regressions; 95% CIs and p-values were estimated from bootstrap procedures with 499 replications. Mean cost differences (MCD) PPPY were compared during the observation period between matched cohorts by calculating the difference in mean costs PPPY between the PP1M and OAA cohorts; 95% CIs and p-values were obtained from non-parametric bootstrap procedures with 499 replications.

Results

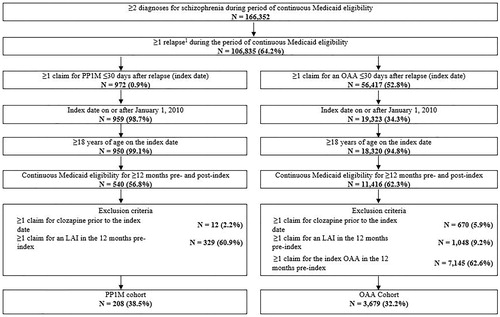

In total, 208 and 3679 patients met all selection criteria and were included in the PP1M and OAA cohorts, respectively (). The 208 patients in the PP1M cohort were matched to 624 patients in the OAA cohort.

Figure 1. Identification of the study population. Abbreviations: LAI, long-acting injectable; OAA, oral atypical antipsychotic; PP1M, once-monthly paliperidone palmitate Note:1Relapse was defined as an inpatient admission or emergency room visit with a diagnosis code for schizophrenia.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics between the matched PP1M and OAA cohorts were well-balanced ( presents baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, presents baseline HRU and costs). Mean age was 38.9 (standard deviation [SD]=14.3) in the PP1M cohort, and 40.5 (SD=14.0) and 39.9 (SD=14.2) years in the unmatched and matched OAA cohorts, respectively. A proportion of 35.6%, 47.5%, and 34.6% of patients were females in the PP1M cohort and in the unmatched and matched OAA cohorts, respectively. Mean Quan-CCI score was 0.9 in both matched cohorts and 1.2 among the unmatched OAA cohort. On average, patients in the matched PP1M and OAA cohorts had 3.2 (SD=12.9) and 2.7 (SD=3.8) schizophrenia-related relapses prior to the index date; patients in the unmatched OAA cohort had 2.4 (SD=3.7) schizophrenia-related relapses prior to the index date. In total, 55.8%, 60.5%, and 55.1% of patients in the PP1M cohort and the unmatched and matched OAA cohorts had depression, respectively, and 45.7%, 49.3%, and 47.1% had substance-related and addictive disorders, respectively.

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics in the overall and matched PP1M and OAA cohortsa.

Table 2. Healthcare resource utilization and healthcare costs PPPY during the 12-month baseline period.

Adherence

Mean PDC for the index medication at 6 months of follow-up was higher in the PP1M cohort (52.6%) than in the matched OAA cohort (46.2%, p=.013). A similar trend was observed at 12 months (mean PDC: 41.2% vs. 34.7%, p=.008).

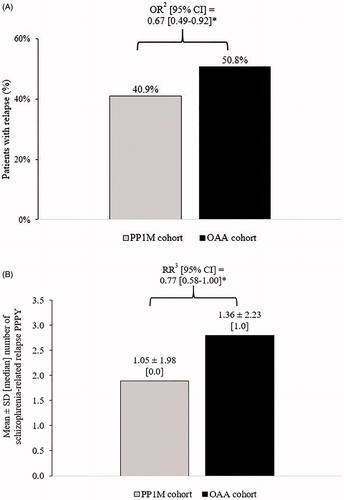

Subsequent relapses

The odds of having ≥1 subsequent schizophrenia-related relapse were 33% lower in the PP1M cohort relative to the matched OAA cohort (p=.013; ). The number of subsequent schizophrenia-related relapses was 23% lower in the PP1M cohort compared with the matched OAA cohort (p=.048).

Figure 2. Comparison of (A) the proportion of patients with subsequent schizophrenia-related relapses1 and (B) the number of subsequent schizophrenia-related relapses PPPY in the PP1M and OAA cohorts during the 12-month follow-up period. Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval; OAA, oral atypical antipsychotics; OR, odds ratio; RR, rate ratio; PPPY, per patient per year; PP1M, once-monthly paliperidone palmitate; SD, standard deviation. Notes. *Significant at the 5% level. 1Relapse was defined as an inpatient admission or emergency room visit with a diagnosis for schizophrenia. 2ORs (binary variables) including CIs and p-values were estimated using logistic regression models. 3RRs (count variables) were estimated using Poisson regression models. CIs and p-values for RRs were estimated from a non-parametric bootstrap procedure (N = 499).

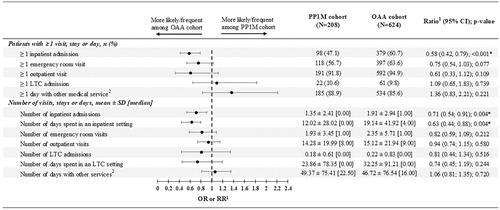

Healthcare resource utilization

Patients in the PP1M cohort had 42% lower odds of having ≥1 all-cause inpatient admission than those in the matched OAA cohort (p<.001; ). Relative to patients in the matched OAA cohort, those in the PP1M cohort had 29% fewer inpatient admissions PPPY (p=.004) and 37% fewer days spent PPPY in an inpatient setting (p=.004).

Figure 3. Comparison of all-cause healthcare resource utilization PPPY between PP1M and OAA cohorts. Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval; LTC, long-term care; OAA, oral atypical antipsychotic; OR, odds ratio; PPPY, per patient per year; PP1M, once-monthly paliperidone palmitate; RR, rate ratio; SD, standard deviation. Notes. *significant at the 5% level. 1Odds ratios (binary variables) including CIs and p-values were estimated using logistic regression models. Rate ratios (count variables) were estimated using Poisson regression models. CIs and p-values for rate ratios were estimated from a non-parametric bootstrap procedure (N = 499). 2Other services included mental-health institute admissions, one-day mental-health institute outpatient visits, home care, and other services.

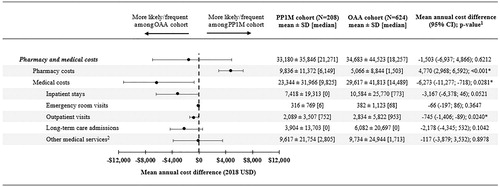

Healthcare costs

Patients in the PP1M cohort had significantly lower all-cause PPPY medical costs compared with those in the matched OAA cohort (MCD=−$6273; p=.028; ). This difference was driven by numerically lower all-cause PPPY inpatient costs (MCD=−$3167; p=.052), significantly lower all-cause PPPY outpatient costs (MCD=−$745; p=.024), as well as numerically lower all-cause PPPY long-term care costs (MCD=−$2178; p=.104). The difference in medical costs offset the $4770 higher PPPY pharmacy costs (p<.001) of patients in the PP1M cohort, resulting in a statistically non-significant difference in total healthcare costs between the two cohorts (MCD=−$1503 PPPY, p=.621).

Figure 4. Comparison of all-cause healthcare costs PPPY between PP1M and OAA cohorts. Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval; LTC, long-term care; MCD, mean cost difference; OAA, oral atypical antipsychotic; PPPY, per patient per year; PP1M, once-monthly paliperidone palmitate; SD, standard deviation; US, United States. Notes. *significant at the 5% level. 1Estimated using an ordinary least squares regression model. CIs and p-values were estimated from a non-parametric bootstrap procedure (N = 499). 2Other services included mental-health institute admissions, one-day mental-health institute outpatient visits, home care, and other services.

Discussion

In this retrospective observational study among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia who had a recent schizophrenia-related relapse, PP1M-treated patients exhibited significantly higher adherence to the index AP medication and had significantly fewer subsequent schizophrenia-related relapses than matched OAA-treated patients. The number of all-cause inpatient admissions was significantly lower among PP1M-treated patients relative to matched OAA-treated patients. PP1M-treated patients had significantly lower all-cause PPPY medical costs which offset the higher PPPY pharmacy costs, resulting in a statistically non-significant cost difference between the two cohorts.

These results are consistent with two previous real-world studies of adults with schizophrenia, although only Medicaid beneficiaries were included in the current studyCitation20,Citation21. A 2015 study reported that the risk of schizophrenia-related relapse was significantly reduced in PP1M-treated patients relative to OAA-treated patients 12 months after an index hospitalization (hazard ratio [95% CI]=0.68 [0.66–0.71])Citation20. In another more recent study by Pilon et al., PP1M-treated patients had significantly lower odds of experiencing a schizophrenia-related rehospitalization at 30, 60, and 90 days post-discharge (e.g. 90 days: OR [95% CI]=0.80 [0.71–0.91])Citation21. The effect size observed in the current study (OR [95% CI]=0.67 [0.49–0.92]) was larger than that observed by Pilon et al., which may be attributed to the definition of the outcome (i.e. rehospitalization only vs. rehospitalization or ER visit in the current study), differences in the study populations (patients with any health insurance type vs. Medicaid beneficiaries), and the different length of follow-up (Pilon et al.: up to 90 days, present study: 12 months)Citation21.

In the current study, the occurrence of inpatient admissions was 42% lower among PP1M-treated patients vs. OAA-treated patients. This result is corroborated by a study from Baser et al. which included veterans with schizophrenia (with or without a recent schizophrenia-related relapse)Citation19. In this study, the rates of inpatient admissions were significantly lower in the PP1M cohort than in the OAA cohortCitation19. However, two other studies that also focused on different populations (i.e. patients with any type of coverage, with or without a recent relapse) reported either more modest, or statistically non-significant differences in inpatient admissionsCitation14. This apparent discrepancy may be attributed to the particularly high risk of non-adherence in the present study population. In fact, nearly half of patients in both cohorts had substance-related and addictive disorders, which is one of the most consistently reported risk factors for non-adherence and relapseCitation11,Citation28,Citation29. Nevertheless, the mean PDC was significantly higher in the PP1M cohort than in the OAA cohort, which is consistent with the large body of evidence supporting that PP1M treatment is associated with better AP adherence than OAAsCitation14,Citation17,Citation18.

The present study’s findings are also consistent with the outcomes of two randomized controlled trialsCitation22–24. Among a population of patients with schizophrenia recently released from incarceration, PP1M demonstrated superiority over oral APs in terms of delayed time to first treatment failure, as well as reduced rates of treatment failure and institutionalizationCitation22,Citation23. Similar conclusions were drawn among a population of patients recently diagnosed with schizophrenia (i.e. within 1–5 years) with at least two schizophrenia-related relapses in the past 24 months, where the time to subsequent relapse was significantly longer among patients treated with PP1M compared to oral APsCitation24.

Limitations

The present study is subject to some limitations. First, the rates of subsequent schizophrenia-related relapses may have been underreported if relapses resulted in alternative consequences unobservable in medical claims data (e.g. incarceration) and because the reason for using APs (e.g. because of a relapse) was not available in the data. Second, the requirement of a fixed 12-month eligibility period post-index may have led to immortal time bias (i.e. patients with schizophrenia who were well-controlled may have been selected and patients with more severe symptoms who were lost to institutionalization may have been excluded). Third, while the current study contains data from six states, >75% of identified patients were from Missouri, which in addition to the small sample size, observational nature of the study, and the lack of representation of patients without health insurance or with non-Medicaid insurance plans limit the generalizability of findings. Fourth, claims databases may contain omissions and inaccuracies, but this limitation should not impact differences between cohorts. Fifth, analyses did not account for Medicaid rebates, which implies that the real pharmacy costs paid by Medicaid have been overestimated. Sixth, as with all claims database studies, prescription fills did not account for whether the dispensed medication was taken as prescribed, thereby potentially overestimating adherence. Seventh, PP1M or OAA initiations during an inpatient stay could not be observed in this claims database; therefore, it is possible that PP1M or OAA had been initiated during the relapse that occurred within 30 days prior to the index date. Lastly, this observational claims-based study may have been subject to residual confounding due to unmeasured confounders (i.e. information not available in claims was not captured in the current study). It may also be subject to confounding by indication, since patients may have been initiated on PP1M because of a lack of response to oral APs.

Conclusions

Consistent with findings in other patient populations, Medicaid beneficiaries treated with PP1M and having a recent schizophrenia-related relapse were significantly more adherent to their index AP medication and experienced significantly fewer subsequent schizophrenia-related relapses while remaining a cost neutral therapeutic option compared with those treated with OAAs. More specifically, relative to patients treated with OAAs, those treated with PP1M incurred significantly lower medical costs which fully offset higher pharmacy costs, resulting in a statistically non-significant difference in total healthcare costs.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The sponsor had a role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

BE, LM, MHL, and PL are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript. CP, DL, EK and KJ are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC and stockholders of Johnson & Johnson.

Author contributions

CP, BE, LM, MHL, PL, DL, EK and KJ contributed to the conception and design of the current study. Analyses were carried out by BE, LM, MHL, and PL. CP, BE, LM, MHL, PL, DL, EK and KJ were involved in interpreting the findings, drafting the manuscript, and approving the final version. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Samuel Rochette and Gloria DeWalt, employees of Analysis Group, Inc., which provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC to conduct this study.

Reviewer disclosures

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they received honoraria and/or research grants from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, MINECO, the Catalan Pons Balmes Grant, Fundació la Marató de TV3 of Catalonia, Janssen-Cilag, GlaxoSmithKline, Ferrer and ADAMED. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Previous presentations

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the US Psychiatric and Mental Health Congress 2019, held in San Diego, CA, October 3-6, 2019.

References

- Kahn RS, Sommer IE, Murray RM, et al. Schizophrenia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15067.

- Work Group on Schizophrenia. 2010. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia – second edition [cited 2019 Nov 27]. Available from: https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/schizophrenia.pdf.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia [cited 2019 Nov 28]. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia.shtml.

- Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):241–247.

- Emsley R, Chiliza B, Asmal L, et al. The nature of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:50.

- Kozma C, Dirani R, Canuso C, et al. Change in employment status over 52 weeks in patients with schizophrenia: an observational study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(2):327–333.

- Takeuchi H, Siu C, Remington G, et al. Does relapse contribute to treatment resistance? Antipsychotic response in first- vs. second-episode schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(6):1036–1042.

- Almond S, Knapp M, Francois C, et al. Relapse in schizophrenia: costs, clinical outcomes and quality of life. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:346–351.

- Hong J, Windmeijer F, Novick D, et al. The cost of relapse in patients with schizophrenia in the European SOHO (Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes) study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(5):835–841.

- Leucht S, Tardy M, Komossa K, et al. Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9831):2063–2071.

- Ascher-Svanum H, Faries DE, Zhu B, et al. Medication adherence and long-term functional outcomes in the treatment of schizophrenia in usual care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(3):453–460.

- Haddad PM, Brain C, Scott J. Nonadherence with antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: challenges and management strategies. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2014;5:43–62.

- Marcus SC, Zummo J, Pettit AR, et al. Antipsychotic adherence and rehospitalization in schizophrenia patients receiving oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics following hospital discharge. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(9):754–768.

- Pilon D, Muser E, Lefebvre P, et al. Adherence, healthcare resource utilization and Medicaid spending associated with once-monthly paliperidone palmitate versus oral atypical antipsychotic treatment among adults recently diagnosed with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):207.

- The University of South Florida. Florida Medicaid drug therapy management program sponsored by the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration; 2020. 2019–2020 Florida Best Practice Psychotherapeutic Medication Guidelines for Adults. [cited 2020 May 6]. Available from: http://floridabhcenter.org/2019-2020-treatment-of-adult-schizophrenia.html

- US Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing Information – INVEGA SUSTENNA [cited 2019 Nov 27]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/022264s029lbl.pdf.

- Pilon D, Tandon N, Lafeuille MH, et al. Treatment patterns, health care resource utilization, and spending in medicaid beneficiaries initiating second-generation long-acting injectable agents versus oral atypical antipsychotics. Clin Ther. 2017;39(10):1972–1985.e2.

- Kamstra R, Pilon D, Lefebvre P, et al. Treatment patterns and Medicaid spending in comorbid schizophrenia populations: once-monthly paliperidone palmitate versus oral atypical antipsychotics. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(8):1377–1388.

- Baser O, Xie L, Pesa J, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs of Veterans Health Administration patients with schizophrenia treated with paliperidone palmitate long-acting injection or oral atypical antipsychotics. J Med Econ. 2015;18(5):357–365.

- Lafeuille MH, Grittner AM, Fortier J, et al. Comparison of rehospitalization rates and associated costs among patients with schizophrenia receiving paliperidone palmitate or oral antipsychotics. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(5):378–389.

- Pilon D, Amos TB, Kamstra R, et al. Short-term rehospitalizations in young adults with schizophrenia treated with once-monthly paliperidone palmitate or oral atypical antipsychotics: a retrospective analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(1):41–49.

- Alphs L, Benson C, Cheshire-Kinney K, et al. Real-world outcomes of paliperidone palmitate compared to daily oral antipsychotic therapy in schizophrenia: a randomized, open-label, review board-blinded 15-month study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):554–561.

- Alphs L, Mao L, Lynn Starr H, et al. A pragmatic analysis comparing once-monthly paliperidone palmitate versus daily oral antipsychotic treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;170(2–3):259–264.

- Schreiner A, Aadamsoo K, Altamura AC, et al. Paliperidone palmitate versus oral antipsychotics in recently diagnosed schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;169(1–3):393–399.

- Dilla T, Ciudad A, Álvarez M. Systematic review of the economic aspects of nonadherence to antipsychotic medication in patients with schizophrenia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:275–284.

- Thieda P, Beard S, Richter A, et al. An economic review of compliance with medication therapy in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(4):508–516.

- Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation. 2009;38(6):1228–1234.

- Alvarez-Jimenez M, Priede A, Hetrick SE, et al. Risk factors for relapse following treatment for first episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Schizophr Res. 2012;139(1–3):116–128.

- Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(10):892–909.