Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) burden associated with postpartum depression (PPD), determine the extent to which clinical response impacts HRQoL, and estimate the impact of PPD and clinical response on healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and productivity.

Methods

Patient data (n = 127) from two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of brexanolone injection in adults with PPD were employed for these posthoc analyses. HRQoL and health utility was assessed with the SF-36-v2 Health Survey (SF-36v2) acute version. The 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD-17) total score was used to identify clinical response (≥50% reduction in HAMD-17 total score). Baseline HRQoL burden was assessed by comparison to age- and gender-adjusted population normative data from the 2009 QualityMetric PRO Norming study. The impact of clinical response was evaluated by comparing day 7 and day 30 SF-36v2 scores between clinical responders and non-responders. Interpretations of the meaningfulness of clinical response were indirectly estimated via 2017 National Health and Wellness Survey data linking SF-36v2 mental component summary (MCS) scores to (HRU) and productivity.

Results

Baseline HRQoL of patients with PPD was significantly below normative values. Day 7 and day 30 clinical response were associated with large and statistically significant improvements in HRQoL, greater likelihood of meeting SF-36v2 responder definitions, and reduced impairment. MCS levels corresponding to those observed in clinical responders were linked to lower HRU and productivity loss relative to non-responders.

Conclusions

PPD places a substantial burden on HRQoL. Achievement of rapid clinical response (at day 7) and clinical response sustained several weeks following the end of treatment (day 30) led to significant improvement in HRQoL, suggesting the importance of identifying women with PPD and providing effective treatment options.

Introduction

Postpartum depression (PPD) is one of the most common medical complications during and after pregnancy, affecting an estimated 13.2% of women giving birth in the United States and 17.7% globallyCitation1–7. Up to 30% of women with PPD may have depressive symptoms persisting at least a year postpartumCitation8. Suicide is strongly associated with depressive symptoms and is a leading cause of pregnancy-related mortalityCitation9–16. Mothers with PPD may experience difficulties with functioning and bonding with their infantsCitation17,Citation18. The impact of PPD on offspring can be substantial, with long-term detrimental effects on cognitive, psychological and physical outcomes in children of women with PPDCitation19–22.

Fully capturing the burden of depression, its treatment, and actively evaluating the degree to which a new therapy alleviates this burden can be a challenge and must include more than only assessing changes in clinical symptoms. It has been shown that the impact of depressive clinical symptoms extends well beyond abnormalities in mood and neurovegetative symptoms to also include multiple aspects of psychological well-being, social and role function, and physical functioningCitation23–29. It is therefore crucial that clinical trials of new therapies for depression incorporate patient-reported outcomes (PROs) to systematically evaluate how treatment impacts patients’ overall functioning and well-being; PROs are increasingly used as endpoints in clinical trialsCitation30–33.

One of the most widely used PROs for measuring patient functioning and well-being is the SF-36 Health Survey (SF-36). The SF-36 is a general health status instrument that measures eight domains of functional health status and well-being, including physical, social and role functioning, general health status, vitality and psychological well-being. The instrument was constructed for use in health policy evaluations, general population surveys, clinical research and practice, other applications involving diverse patient populations, and can be scored as a preference-based measure to provide utility data for economic evaluationCitation34,Citation35. A systematic review of PROs used in randomized controlled clinical trials also found the SF-36 to be the most widely used instrument in registered clinical trialsCitation30. Initial development and validation studies of the SF-36 confirmed the extensive health-related quality of life (HRQoL) burden associated with depression when scores were compared with those of other chronic diseases and the general populationCitation36,Citation37. Significant and meaningful improvements in SF-36 scale and summary measure scores have been shown among patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) with clinical response and remission, including those who were determined to be responders and remitters as defined by improvement in the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17)Citation38–41. In these studies, responders and remitters showed significantly greater improvement in all or most SF-36 scales when compared to non-responders.

Similar to findings in MDD, PPD has been shown to produce significant impairment in many aspects of HRQoL as measured with the SF-36, including physical, social and role functioning, general health perceptions, vitality and psychological well-beingCitation20,Citation42–44. However, to our knowledge, no studies have investigated the impact of clinical response to PPD treatment on HRQoL. The present analysis sought to further define the HRQoL burden associated with PPD and to determine the extent to which a clinical response impacts HRQoL. Interpretation guidelines and indirect estimation of healthcare resource utilization and productivity loss were utilized to understand the meaningfulness of HRQoL burden and improvements associated with clinical response.

Methods

Sample

The data for this post-hoc analysis come from two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trials, conducted under breakthrough therapy designation, and designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of brexanolone injection in adults with moderate-to-severe PPD (NCT02942004 and NCT02942017). Details of the trial design and patient samples are described elsewhereCitation45. Women were eligible to participate if they were aged 18–45 years, 6 months postpartum or less at the time of the study, with a diagnosis of moderate to severe PPD and a qualifying HAMD-17 total score (Study 1: ≥26; Study 2: 20‒25). Individuals were excluded from the study if they had active psychosis, medical history of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or schizoaffective disorder, had attempted suicide during the current episode of postpartum depression, or a history of alcohol or drug abuse in the previous 12 months. Participants were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive a single intravenous injection of either brexanolone 90 µg/kg/hr, brexanolone 60 µg/kg/hr, or placebo for 60 h in Study 1 or (1:1) brexanolone 90 µg/kg/hr or placebo for 60 h in Study 2. The trials were conducted under an umbrella protocol allowing for integrated analysis; the integrated efficacy dataset, which includes patients who were randomized to either the recommended brexanolone 90 µg/kg/hr (BRX) dose or placebo, was employed herein.

Outcome measures

The primary efficacy outcome measure in both trials was the least-squares mean difference in the HAMD-17 total score from baseline to 60 h. The HAMD-17 is a clinician-administered instrument to assess the severity of depressionCitation46. Response (improvement in depression symptoms) was defined as having a 50% or greater reduction from baseline in HAMD-17 total score.

The SF-36v2 is a 36 item, self-report survey of functional health and well-beingCitation35,Citation47. In both brexanolone trials, the acute form of the SF-36v2 was administered, which has a 1-week recall period. Responses to 35 of the 36 items are used to compute an 8-domain profile of functional health and well-being scores. The 8-domain profile consists of the following subscales: Physical Functioning (PF), Role Limitations due to Physical Health (RP), Bodily Pain (BP), General Health Perceptions (GH), Vitality (VT), Social Functioning (SF), Role Limitations due to Emotional Problems (RE), and Mental Health (MH). Psychometrically-based physical and mental health component summary scores (PCS and MCS, respectively) are computed from the eight domain scores to give a broader metric of physical and mental HRQoL. The eight SF-36v2 scales and two summary measures are scored using norm-based methods that standardize the scores to a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 in the general US population, with higher scores indicative of better health status. Minimal important difference thresholds to evaluate the meaningfulness of group mean differences, as well as patient-level responder definitions, have previously been defined for each SF-36v2 domain and the component scoresCitation47. Lastly, a subset of items is used to derive 6 domains that are scored to produce a single health-state utility index, the SF-6DCitation34. Utility scores range from 0 (dead) to 1(full health); the SF-6D ranges from 0.301 to 1.

The SF-36v2 was added to the trials as an exploratory endpoint by protocol amendment, and therefore was completed by a subset of patients in the clinical trials. Both the HAMD-17 and SF-36v2 were administered at baseline, and days 7, 14, 21 and 30. The focus of these analyses will be on baseline and day 7 (the earliest post-treatment timepoint with both HAMD-17 and SF-36v2 assessment). Parallel analyses were also conducted on day 30, as the latest post-treatment timepoint available.

Statistical analyses

The analytic sample was comprised of all patients with available HAMD-17 and SF-36v2 at one or both of baseline or day 7. All analyses were conducted using all data available for the specific analysis and employing pooled data between the BRX and placebo study groups, in order to maximize the sample size available for analysis. Demographic and clinical characteristics for all clinical trial participants contributing any data were summarized using frequencies for categorical measures and means and standard deviations for continuous measures. Statistical significance was not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Health-related quality of life burden of postpartum depression

General population normative data used to estimate the burden of PPD on HRQoL came from the internet-based 2009 QualityMetric PRO Norming StudyCitation47. The sample was drawn from a national probability sample of US non-institutionalized adults drawn from the KnowledgePanelFootnotei, which was maintained by Knowledge Networks. The data from the norming study were adjusted to the age and gender of the PPD trial sample using separate least squares multiple regression models for each SF-36v2 scale and summary measure score. Student’s t-tests were conducted to test for statistical significance of differences in SF-36v2 scores between the BRX trial sample and the adjusted general population norms. Cohen’s effect size for standardized differences was calculated to help interpret the magnitude of the difference in mean scores between samplesCitation48. In addition, the percentage of patients with PPD who score meaningfully below the general population norm was determined. A patient’s baseline SF-36v2 score was considered below the norm if the score difference from the norm was greater than 1.96 standard errors of measurement (SEM), which represents the 95% confidence interval around an individual patient score. We hypothesized that patients with PPD would have SF-36v2 scale and summary measure scores significantly below the general population.

Health-related quality of life and clinical response

The impact of a clinical response on HRQoL was investigated in several ways to provide meaningful interpretations of outcomes. Clinical response was assessed at day 7 and day 30, and defined as a 50% improvement in HAMD-17 total score from baseline to the time of assessment. Day 7 was selected for evaluating the impact of a clinical response on HRQoL this was the earliest post-baseline timepoint with both HAMD-17 and SF-36v2 assessments available and therefore the data closest to the time point of the trials’ primary endpoint (60 h post-baseline). Day 30 analyses were also conducted to assess the longer-term impact of clinical response on HRQoL, as this was the latest post-treatment timepoint available (4 weeks post-treatment).

First, mean changes in SF-36v2 scale, summary measures and SF-6D scores from baseline to day 7 and from baseline to day 30 were compared within and between HAMD-17 responders and non-responders. Student’s t-tests were conducted to test for the statistical significance of the change from baseline to day 7 and day 30 and the differences in mean change scores between HAMD-17 responders and non-responders. Mean differences between these groups were interpreted in light of previously established minimal important difference thresholds. We hypothesized that HAMD-17 responders would show a significant change from baseline in SF-36v2 scale, summary measures and SF-6D scores at both day 7 and day 30, and significantly greater change as compared to non-responders. Analyses also were conducted on each of the SF-36v2 scales and summary measures and SF-6D using the responder definition established for each measure to examine group differences in the percentage of patients who showed a meaningful decline (change from baseline to day 7/day 30 ≤ −1*responder definition), meaningful improvement (change from baseline to day 7/day 30 ≥ responder definition), or no change (change from baseline to day 7/day 30 within ± responder definition)Citation47. Chi-square tests were conducted to assess whether the proportion of patients in each of these three SF-36v2 change score categories differed between HAMD-17 responder and non-responder groups. We hypothesized that a larger proportion of HAMD-17 responders would show meaningful improvement at both day 7 and day 30, as compared with non-responders.

The meaningfulness of clinical response was further evaluated by comparing mean SF-36v2 scores at day 7 and day 30 to age- and gender-adjusted population norms stratified by HAMD-17 response status, in order to assess the extent to which HAMD-17 responders would be more likely to achieve normal HRQoL levels compared to HAMD-17 non-responders. We hypothesized that mean SF-36v2 scores of HAMD-17 responders at both day 7 and day 30, would meet or exceed normal HRQoL levels, defined as being within the established minimal important difference thresholds of normative levels, whereas non-responders would not meet normal HRQoL levels.

To interpret the meaning of changes in HRQoL scores associated with clinical response in terms of their impact on patients’ daily functioning, responses to specific items of the SF-36v2 at baseline and day 7 as well as baseline and day 30 were compared between HAMD-17 responders and non-responders. Specifically, the percentages of patients whose item-level response indicated a high level of impairment (response options of “all of the time” or “most of the time”) at baseline and day 7/day 30 were compared for selected SF-36v2 scale items. All items selected for this analysis contribute to scales most related to mental health status (mental health, role emotional, social functioning and vitality), which were expected to be the most responsive to changes in depression status. We hypothesized that, despite similar levels of high impairment at baseline, a smaller percentage of HAMD-17 responders would show high impairment at both day 7 and day 30, as compared with non-responders.

Lastly, data from the 2017 National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS) were used to indirectly estimate differences in the utilization of psychiatrist/psychologist services and work productivity based on SF-36v2 MCS scores at baseline, and as observed for responders and non-responders at day 7 and day 30Citation49. MCS was selected since this measure represents the four SF-36v2 scales most related to mental health status, where the largest response in scores was observed in this study. A subset of the NHWS data that matched the brexanolone trial sample in terms of age, gender, and depression diagnosis was used. We hypothesized that higher levels of MCS would correspond to less utilization of psychiatrist/psychologist services and missed work, and further that a greater proportion of HAMD-17 responders would reach higher MCS levels at day 7 and day 30 as compared to non-responders.

Results

Overall 127 patients were included in the analytic sample, with a mean age of 27 years and a mean baseline HAMD-17 score of 25 (). In total, 87 patients were white (67%), 34 (27%) were black or African-American, and 21 (17%) were Hispanic or Latino. Over 40% of patients had a history of depression (44%) or anxiety (43%). Prior history of PPD was present in 39% of patients (64% with a prior birth), and 28% had a family history of PPD. A higher proportion of patients had onset of PPD during four weeks postpartum (75%) than during the third trimester (25%) and 26% of patients were taking concomitant antidepressants at baseline.

Table 1. Baseline demographics and characteristics for clinical trial patients with PPD contributing to analytic sample (n = 127).

Health-related quality of life burden of postpartum depression

Comparisons with age- and gender-adjusted general population norms revealed that the HRQoL of patients with PPD was significantly below normative values for all SF-36v2 scales, the mental summary measure, and the SF-6D (). Differences were greatest in the SF-36v2 domains of vitality, social functioning, role emotional and mental health, and the mental health summary measure, with scores 1 to 1.5 standard deviations below normative values, all large effect size differences (Cohen’s d > 0.8). Furthermore, more than 80% of patients with PPD scored meaningfully below the age- and gender-adjusted norm on each of these scales. Mean score differences on the physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain and general health scales between patients with PPD and general population norms were in the small (0.2 > Cohen’s d < 0.5) to moderate effect size range (0.5 > Cohen’s d < 0.8) and more than one-third of patients with PPD scored meaningfully below the normative values across these physical health scales.

Table 2. Comparison of baseline SF-36v2 Health Survey Scale scores between patients with PPD and adjusted general population norms.

Health-related quality of life and clinical response

Patients with PPD with HAMD-17 response at day 7 showed large and statistically significant improvements in all SF-36v2 scales, the mental summary measure and the SF-6D as did those with the response at day 30 (). Excluding the physical summary measure, the mean improvement in scores ranged from 4.76 to 25.44 points on day 7 and from 6.20 to 29.56 on day 30, which are all larger than the minimal important change in scores established for these SF-36v2 scales and score improvements of this magnitude are in the moderate to the large effect size range. Scales most related to mental health status showed the greatest mean score improvements, approaching or exceeding 2 standard deviations on the vitality, social functioning, role emotional, mental health, and mental summary scales. Meaningful improvement in scores was also observed on many of the SF-36v2 scales and the SF-6D for day 7 and day 30 HAMD-17 non-responders. Specifically, the mean improvement on the role physical, vitality, social functioning, role emotional and mental health scales, the mental summary measure and the SF-6D all exceeded the minimal important change established for these scales at both day 7 and day 30, as well as physical functioning at day 30. Significant differences in mean score improvement were observed between HAMD-17 responders and non-responders on the SF-36 v2 bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional and mental health scales, the mental summary measure and SF-6D at both day 7 and day 30. The mean differences between groups were most prominent on those SF-36v2 scales related to mental health status where mean differences were all in the large effect size range.

Table 3. Mean and categorical changes in SF-36v2 scale scores from baseline to day 7 and to day 30 by HAMD-17 clinical response status.

In both groups, a greater percentage of patients showed better outcomes than worse outcomes across all SF-36v2 scales, summary measures, and the SF-6D (). Significant differences in the categories of change favoring the responders were observed on the general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional and mental health scales, the mental summary measure, and SF-6D. For each of these scales, except the general health scale, more than 80% of responders had a better outcome, which was nearly double the percentage of better outcomes observed for the non-responders. On day 30, significant differences in the categories of change favoring the responders were observed on the bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, and mental health scales, the mental summary measure, and SF-6D ().

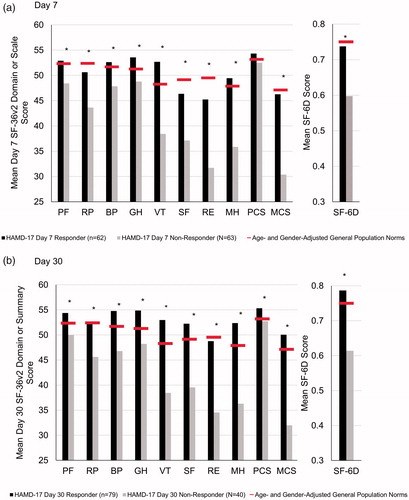

presents mean SF-36v2 scores at day 7 and day 30 for both groups compared to age- and gender-adjusted norms. As shown, day 7 SF-36v2 scores were significantly higher among HAMD-17 responders compared to non-responders across all scales except the physical summary measure, and day 30 scores were higher across all scales. The differences in scores were more pronounced among scales most related to mental health status. Scores of clinical responders met (within the established minimal important difference thresholds) or exceeded adjusted normative values on the physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, vitality, and mental health scales and the physical summary measure at day 7 and met or exceeded normative values for all scales at day 30. Where significant differences were observed, the SF-36v2 scores of non-responders remained well below adjusted normative values, with the exception of physical functioning and the physical health component summary at day 30.

Figure 1. Comparison of day 7 (A) and day 30 (B) SF-36v2 Health Survey scale scores between patients with PPD stratified by clinical response status and age- and gender-adjusted general population norms. *p < .05. Abbreviations. PF, physical functioning; RP, role physical; BP, bodily pain; GH; general health; VT, vitality; SF, social functioning; RE, role emotional; MH, mental health; PCS, physical component summary; MCS, mental component summary; HAMD-17, 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; PPD, postpartum depression

As a basis for interpreting the changes in HRQoL scores from baseline to day 7 and to day 30, the content of SF-36v2 items most related to mental health status was examined. As shown in , the percentage of HAMD-17 responders reporting “feeling tired” all or most of the time in the past week dropped from 88.3% at baseline to 29.0% at day 7. Comparatively, 93.4% of non-responders reported “feeling tired” all or most of the time in the past week at baseline, which only declined to 69.8% at day 7. Similar patterns were observed for being full of energy, health interfering with social activities, emotional health causing less productivity at work, feeling calm and peaceful, and feeling downhearted and depressed, with substantially larger declines in the proportion of patients showing high levels of impairment for responders as compared to non-responders. A similar pattern of results also was found at day 30 ().

Table 4. Item content-based interpretation of SF-36v2 scales most related to mental health status by HAMD-17 clinical response status.

presents the link between day 7 and day 30 SF-36v2 MCS score categories and health care utilization and missed days at work as derived from the 2017 NHWS. At baseline, 73% of patients in the brexanolone trials had MCS scores corresponding to the lowest category (<25) with a mean score of 20.8. This MCS level in the NHWS sample of young women (ages 18–45) with depressive symptoms in the US corresponded to 42.3% having 1 or more visits to a psychiatrist/psychologist in a 6 month period, with a mean number of visits of 10.9, and over one-quarter (26.0%) missing one or more days at work in the past 7 days (mean hours missed = 5.62). On day 7, 56% of HAMD-17 responders had scores of 45 or higher, with a mean score of 46.3, corresponding in the NHWS sample to a category of MCS scores where only 24.1% of young women in the US reported 1 or more visits to a psychiatrist/psychologist in the last 6 months (mean number of visits among those with at least one = 7.77) and only 5.6% reported missing one or more days at work in the past 7 days (mean hours missed = 1.18). In contrast, only 10% of day 7 HAMD-17 non-responders had MCS scores of 45 or above. At day 30, 74.7% of HAMD-17 responders had MCS scores of 45 or higher, with a mean score of 50.0, corresponding in the NHWS sample to a category of MCS scores where only 21.0% of young women in the US reported at least one visit to a psychiatrist/psychologist in the last 6 months (mean number of visits among those with at least one = 5.91) and 7.4% missed one or more days of work in the past 7 days (mean hours missed = 1.45). Among HAMD-17 non-responders at day 30, 20.0% had MCS scores of 45 or above.

Table 5. Estimates of baseline, day 7, and day 30SF-36v2 mental health component summary score distributions and corresponding estimates of visits to psychiatrist or psychologist in the last 6 months and missed work days.

Discussion

The results of this post-hoc analysis suggest that patients with PPD had a significantly lower HRQoL level than the general population and that those patients who respond to treatment experienced rapid improvement in HRQoL to levels similar to those observed in the general population, indicative of reductions in healthcare resource utilization and productivity loss.

Overall, prior to treatment, patients with PPD reported substantially diminished functioning and well-being, compared to age- and gender-adjusted general population norms for the SF-36v2 Health Survey. The burden of PPD was most pronounced on SF-36v2 measures of mental health status, including psychological distress, role limitations due to emotional health, social functioning, and vitality. However, a substantial burden was also observed on measures related to physical health status. Comparisons with other conditions suggest that the HRQoL burden of PPD observed in this study should be considered clinically significantCitation36,Citation37,Citation50. For example, the profile of SF-36v2 scores was equal to or worse than that of conditions with well-known morbidities, such as MDD, heart disease, chronic migraine headaches, and rheumatoid arthritisCitation24,Citation36,Citation37,Citation50,Citation51. These findings help to fill a gap in evidence documenting the HRQoL burden associated with PPDCitation20.

Analyses conducted to evaluate the HRQoL impact of clinical response as derived from changes in HAMD-17 scores showed those patients who met the clinical response criteria also recovered rapidly as measured by HRQoL. On day 7, the mean improvement in SF-36v2 scores among responders was significant and the magnitude of change was in the moderate to the large effect size range. Analysis of categorical changes in SF-36v2 scores also showed a significantly greater proportion of HAMD-17 responders getting “better” by an amount determined to be clinically meaningful for nearly all SF-36v2 scales compared to non-responders. More importantly, the SF-36v2 scores of HAMD-17 responders approached or exceeded age- and gender-adjusted general population norms at day 7 while the scores of non-responders remained considerably below the norms. A similar pattern of results found at day 30 suggests improvements in HRQoL can be sustained beyond the end of treatment.

Since the interpretation of change in HRQoL scale scores is not always intuitive, another strategy used to interpret the impact of a clinical response on HRQoL was the analysis of item-level response data. For example, more than 75% of patients at baseline reported accomplishing less at work during the past 7 days on an item from the SF-36v2 role emotional scale. On day 7, the percentage of HAMD-17 responders who reported accomplishing less at work dropped to 14.5%, while 47.6% of HAMD-17 non-responders continued to report accomplishing less at work. Similar trends were observed on other SF-36v2 items evaluated.

Lastly, indirect estimates associated with SF-36 MCS score categories, healthcare utilization, and missed days at work (as derived from the 2017 NHWS) were used to interpret the meaningfulness of clinical response in this study. The magnitude of improvement in MCS scores observed in this study among HAMD-17 responders was indicative of significant reductions in the likelihood of visits to a psychologist/psychiatrist and missed time at work.

Clinical implications

The profound improvement in HRQoL observed for HAMD-17 responders relative to non-responders highlights the importance of effectively treating patients with PPD. Approximately half of women with PPD go undiagnosed and over 80% go untreatedCitation52,Citation53, suggesting the substantial pre-treatment HRQoL burden observed in this study is unaddressed in most women experiencing PPD. Given the evidence suggesting that PPD symptoms commonly persist beyond the first postnatal year and can substantially impact children and familyCitation8,Citation21, this lack of treatment represents a significant public health concern. Furthermore, data presented herein suggest that women with PPD who receive effective treatment can experience improvement in HRQoL, and that this can extend beyond the end of treatment (day 30, 4 weeks post-treatment). These improvements may translate into not only a substantial reduction in the humanistic burden of depression but also reductions in healthcare resource utilization and productivity loss.

Clinicians including primary care physicians, obstetricians and gynecologists, and pediatricians can significantly improve the identification of PPD by using standardized, validated screening tools, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale or Patient Health Questionnaire 9 during prenatal and postnatal clinical interactions following recommendations by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the US Preventive Services Task ForceCitation54,Citation55. Once identified, management of the patient should follow a stepped-care approach, with treatment intensity matched to the severity of symptoms, the acuteness of presentation, and prior history of response to treatmentCitation56,Citation57.

A recent cost-effectiveness analysis indicates that treatment of adults with PPD symptoms with brexanolone is cost-effective, based on a United States health care payer perspective, over an 11-year time horizon, particularly for patients with severe symptomsCitation58. While this analysis accounted for improved health-related quality of life and cost savings from lower healthcare resource utilization associated with a reduction in PPD symptoms, it did not account for additional cost savings of reduced productivity loss, consideration of which would likely result in a lower cost-effectiveness ratio.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that the data come from randomized controlled clinical trials. Patients enrolled in these studies may not be representative of the broader population of women with PPD. As such, the HRQoL burden observed in this study may overestimate the HRQoL burden in the broader PPD population. Due to the extent of HRQoL burden observed at baseline in this study, the generalizability of the impact of a clinical response on HRQoL to a broader PPD population may also be limited. Another limitation related to the indirect estimates of resource utilization and productivity by MCS score categories is the assumption of no effect modification in the post-partum population compared to the general population of child-bearing age women used in this study. Finally, the indirect estimates of the impact of clinical response on healthcare resource utilization and productivity would benefit from a prospective evaluation.

Conclusion

To date, few studies have systematically evaluated the HRQoL burden associated with PPD. The findings from this study demonstrated that PPD places a tremendous burden on patients’ HRQoL. Patients’ physical and mental health status was observed to be well below general population norms and equal to or worse than diseases with more well-known morbidity. These findings address an important evidence gap in understanding the humanistic burden of PPD. Further, it was demonstrated that clinical response had a significant impact on HRQoL outcomes. In 7 days, the HRQoL profile of patients who achieved a clinical response was restored to normative levels, and at day 30, four weeks after the end of treatment, patients with a clinical response remained at normative HRQoL levels. Together these findings suggest the importance of identifying women with PPD and providing them with effective treatment options.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Sage Therapeutics, Inc. provided funding for this study.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MEG, MYH, VB, SJK, and AE-L are employees of Sage Therapeutics, Inc. and own stock or stock options in the company. PH was an employee of Sage Therapeutics, Inc. at the time the study was conducted. SM-B reports personal fees from MedScape and grants from Sage Therapeutics, Inc., awarded to the University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill, NC, USA) during the conduct of the brexanolone injection clinical trials and grants from Janssen, PCORI, and the NIH outside the submitted work. MK, SA, and MF are employees of Optum, Acaster Lloyd Consulting, Ltd. and AMF Consulting, respectively, which were paid by Sage Therapeutics to conduct the research reported in this manuscript. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

MEG, MK, SA, MF, AEL conceptualized the study. MF conducted the data analysis. SMB and SJK collected the data. SMB, MYH, VB, PH, and SJK provided critical feedback on design and findings. MEG and MK developed the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors have reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

None.

Notes

i now GfK Custom Research, LLC; http://www.knowledgenetworks.com/ganp/index.html

References

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, et al. Births: final data for 2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(13):1–47.

- Callaghan WM, Kuklina EV, Berg CJ. Trends in postpartum hemorrhage: United States, 1994-2006. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):353.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes during pregnancy. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2018 [cited 2020 March 31]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/diabetes-during-pregnancy.htm

- DeSisto C, Kim SY, Sharma AJ. Prevalence estimates of gestational diabetes mellitus in the United States, pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS), 2007–2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E104.

- Hahn-Holbrook J, Cornwell-Hinrichs T, Anaya I. Economic and health predictors of national postpartum depression prevalence: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of 291 studies from 56 countries. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:248.

- Roberts JM, August PA, Bakris G, et al. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122–1131.

- Bauman BL, Ko JY, Cox S, et al. Vital signs: postpartum depressive symptoms and provider discussions about perinatal depression - United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(19):575–581.

- Vliegen N, Casalin S, Luyten P. The course of postpartum depression: a review of longitudinal studies. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;22(1):1–22.

- Appleby L, Mortensen PB, Faragher EB. Suicide and other causes of mortality after post-partum psychiatric admission. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:209–211.

- Bodnar-Deren S, Klipstein K, Fersh M, et al. Suicidal ideation during the postpartum period. J Womens Health. 2016;25(12):1219–1224.

- Gressier F, Guillard V, Cazas O, et al. Risk factors for suicide attempt in pregnancy and the post-partum period in women with serious mental illnesses. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;84:284–291.

- Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):77–87.

- Mangla K, Hoffman MC, Trumpff C, et al. Maternal self-harm deaths: an unrecognized and preventable outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(4):295–303.

- Moses-Kolko EL, Hipwell AE. First-onset postpartum psychiatric disorders portend high 1-year unnatural-cause mortality risk. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):559–561.

- Palladino CL, Singh V, Campbell J, et al. Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings from the national violent death reporting system. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1056–1063.

- Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths. Report from nine maternal mortality review committees. 2018. Available from: https://reviewtoaction.org/sites/default/files/national-portal-material/ReportfromNineMMRCsfinal_0.pdf.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistcal manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Postpartum depression facts. Rockville (MD): NIMH; 2020 [cited 2020 March 31]. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/postpartum-depression-facts/index.shtml

- Koutra K, Chatzi L, Bagkeris M, et al. Antenatal and postnatal maternal mental health as determinants of infant neurodevelopment at 18 months of age in a mother-child cohort (Rhea Study) in Crete, Greece. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(8):1335–1345.

- Moore Simas TA, Huang M-Y, Patton C, et al. The humanistic burden of postpartum depression: a systematic literature review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(3):383–393.

- Netsi E, Pearson RM, Murray L, et al. Association of persistent and severe postnatal depression with child outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):247–253.

- Surkan PJ, Ettinger AK, Hock RS, et al. Early maternal depressive symptoms and child growth trajectories: a longitudinal analysis of a nationally representative US birth cohort. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:185.

- Coulehan JL, Schulberg HC, Block MR, et al. Treating depressed primary care patients improves their physical, mental, and social functioning. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(10):1113–1120.

- Gaynes BN, Burns BJ, Tweed DL, et al. Depression and health-related quality of life. J Nervous Mental Dis. 2002;190(12):799–806.

- Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, et al. Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(1):11–19.

- Revicki DA, Simon GE, Chan K, et al. Depression, health-related quality of life, and medical cost outcomes of receiving recommended levels of antidepressant treatment. J Family Pract. 1998;47(6):446–452.

- Sobocki P, Ekman M, Agren H, et al. Health-related quality of life measured with EQ-5D in patients treated for depression in primary care. Value in Health. 2007;10(2):153–160.

- Williams JW, Jr, Kerber CA, Mulrow CD, et al. Depressive disorders in primary care: prevalence, functional disability, and identification. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(1):7–12.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Linzer M, et al. Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders. Results from the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1995;274(19):1511–1517.

- Scoggins JF, Patrick DL. The use of patient-reported outcomes instruments in registered clinical trials: evidence from ClinicalTrials.gov. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30(4):289–292.

- Mercieca-Bebber R, King MT, Calvert MJ, et al. The importance of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials and strategies for future optimization. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2018;9:353–367.

- Vodicka E, Kim K, Devine EB, et al. Inclusion of patient-reported outcome measures in registered clinical trials: evidence from ClinicalTrials.gov (2007-2013). Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;43:1–9.

- Carroll J. Gottlieb tackles speculators, FDA transparency and the R&D gold standard in a last round of queries ahead of confirmation vote. Lawrence (KS): Endpoints News; 2017 [cited 2020 March 31]. Available from: https://endpts.com/gottlieb-tackles-speculators-fda-transparency-and-the-rd-gold-standard-in-a-last-round-of-queries-ahead-of-confirmation-vote/

- Brazier J, Usherwood T, Harper R, et al. Deriving a preference-based single index from the UK SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1115–1128.

- Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30(6):473–483.

- Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, et al. SF-36 Health Survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston (MA): The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993.

- Ware J, Kosinski M. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: a manual for users of version 1. Second ed. Lincoln (RI): QualityMetric Incorporated; 2001.

- Beusterien KM, Steinwald B, Ware JE, Jr. Usefulness of the SF-36 Health Survey in measuring health outcomes in the depressed elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1996;9(1):13–21.

- Doraiswamy PM, Khan ZM, Donahue RM, et al. The spectrum of quality-of-life impairments in recurrent geriatric depression. J Gerontol Series A, Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(2):M134–M137.

- Spijker J, Graaf R, Bijl RV, et al. Functional disability and depression in the general population. Results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110(3):208–214.

- Ware JE, Jr., Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, et al. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care. 1995;33(4):AS264–AS279.

- Da Costa D, Dritsa M, Rippen N, et al. Health-related quality of life in postpartum depressed women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(2):95–102.

- Darcy JM, Grzywacz JG, Stephens RL, et al. Maternal depressive symptomatology: 16-month follow-up of infant and maternal health-related quality of life. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(3):249–257.

- Sadat Z, Abedzadeh-Kalahroudi M, Kafaei Atrian M, et al. The impact of postpartum depression on quality of life in women after child’s birth. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(2):e14995.

- Meltzer-Brody S, Colquhoun H, Riesenberg R, et al. Brexanolone injection in post-partum depression: two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1058–1070.

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62.

- Maruish M, editor. User’s manual for the SF-36v2 Health Survey. 3rd ed. Lincoln (RI): QualityMetric Incorporated; 2011.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale (NJ): L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

- Buono JL, Carson RT, Flores NM. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and indirect costs among patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):35.

- Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: a user’s manual. Boston (MA): Health Assessment Lab; 1994.

- Blum SI, Tourkodimitris S, Ruth A. Evaluation of functional health and well-being in patients receiving levomilnacipran ER for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Affective Disord. 2015;170:230–236.

- Cox EQ, Sowa NA, Meltzer-Brody SE, et al. The perinatal depression treatment cascade: baby steps toward improving outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(9):1189–1200.

- Flynn HA, Blow FC, Marcus SM. Rates and predictors of depression treatment among pregnant women in hospital-affiliated obstetrics practices. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(4):289–295.

- ACOG Committee. ACOG committee opinion no. 757: screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(5):1314–1316.

- Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380–387.

- Gjerdingen D, Crow S, McGovern P, et al. Stepped care treatment of postpartum depression: impact on treatment, health, and work outcomes. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(5):473–482.

- Meltzer-Brody S, Howard LM, Bergink V, et al. Postpartum psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18022.

- Eldar-Lissai A, Cohen JT, Meltzer-Brody S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of brexanolone versus selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of postpartum depression in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(5):627–638.