Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to describe treatment sequencing and healthcare costs among chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) patients treated with venetoclax in a US managed care population.

Methods

CLL/SLL patients initiating venetoclax between 04/11/2016 and 06/30/2019 were selected from Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics Data Mart Database. Costs per-patient-per-month were described during the first 60 days of venetoclax-based treatment (initiation phase) and subsequent post-initiation phase. Based on venetoclax prescribing information, clinical event-related costs were identified through claims for tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) diagnosis, monitoring, prophylaxis, immunoglobulin treatment, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, infection, renal impairment, hypertension, or cardiac arrhythmia. Statistical testing was not conducted due to small sample size.

Results

Twenty-five, 30, and 66 patients initiated venetoclax as their first observed regimen (1L), second observed regimen (2L), and third or later observed regimen (3L+), respectively. Most 2L (56.7%) and 3L+ (74.2%) venetoclax recipients previously received ibrutinib. Mean monthly all-cause costs during the initiation phase were $26,429 (1L cohort), $19,580 (2L cohort), and $23,918 (3L + cohort). Among the 2L cohort, mean monthly all-cause [clinical event-related] (including TLS) costs during initiation and post-initiation phases of venetoclax treatment were $15,506 [$6368] (initiation phase) and $14,318 [$5273] (post-initiation phase; median duration: 3.7 months) for patients receiving 1L ibrutinib, and $24,908 [$12,198] (initiation phase) and $16,905 [$7066] (post-initiation phase; median duration: 3.0 months) for patients not receiving 1L ibrutinib.

Conclusions

In this descriptive study, highest mean costs were observed during venetoclax initiation phase. Venetoclax patients previously receiving ibrutinib had lower mean total all-cause and clinical event-related (including TLS) costs during their venetoclax line of therapy than those previously receiving non-ibrutinib therapy.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) is a hematological neoplasm characterized by the accumulation of clonal, mature B-cells in the blood, bone marrow, and spleen [Citation1,Citation2]. It is the most prevalent leukemia among adults in the United States (US) and is projected to cause 4060 deaths in 2020 [Citation3]. Given the prevalence and long survival with this disease, the economic burden of CLL is substantial, with monthly per-patient all-cause costs estimated at $17,442 for recipients of systemic therapy [Citation4].

Seminal advances in the therapeutic management of CLL/SLL have considerably improved patients’ prognosis. The advent of anti-CD20-based chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) was followed by the introduction of targeted therapies, starting with the approval of ibrutinib, which has shown long-term clinical benefits in trials, and followed by the approval of venetoclax and acalabrutinib in first-line (1L) and among patients who received ≥1 prior line of therapy (LOT), and idelalisib and duvelisib among patients who received ≥1 prior LOT [Citation5–12]. The BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of CLL/SLL as single agent in patients with 17p deletion who received ≥1 prior LOT on 04/11/2016 [Citation13], in combination with rituximab in patients who received ≥1 prior LOT on 06/08/2018 [Citation14], and in combination with obinutuzumab as 1L therapy on 05/15/2019 [Citation7]. The efficacy and safety of venetoclax were evaluated in several clinical studies in which it was administered as a single agent [Citation15–19] or in combination with other agents such as obinutuzumab [Citation20–22], rituximab [Citation23–25], and ibrutinib [Citation26].

However, venetoclax is associated with a significant risk of tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), a life-threatening complication of anticancer treatment triggered by the sudden and simultaneous death of cancer cells [Citation27]. Per venetoclax US prescribing information, it is recommended to use a dose ramp-up schedule, TLS prophylaxis, and other monitoring measures (e.g. in-hospital monitoring for patients with medium tumor burden and creatinine clearance rate <80 ml/min or with high tumor burden) to manage the risk of TLS among patients treated with venetoclax [Citation7,Citation27]. In early phase 1 studies conducted with a 2–3 week dose ramp-up schedule, TLS occurred in as many as 13% of patients [Citation7,Citation16,Citation18], whereas the current 5-week dose ramp-up schedule was associated with a TLS risk of ∼2% in subsequent clinical trials [Citation15,Citation17,Citation20,Citation22,Citation25]. A recent real-world study reported a 13.4% rate of TLS even though the vast majority of patients were reportedly managed with adequate TLS prophylaxis, as defined by venetoclax US prescribing information (i.e. allopurinol for all patients regardless of risk category, oral hydration and intravenous normal saline for high risk patients, and rasburicase for patients with elevated baseline uric acid) [Citation7,Citation28]. Phase 2 studies also suggest that ibrutinib single agent prior to initiating venetoclax dose escalation could reduce the risk of TLS after venetoclax initiation. Both studies have shown that following three cycles of ibrutinib prior to venetoclax initiation, the proportion of patients at high risk of TLS was significantly reduced from 13% to 3% and from 24% to 2%, respectively [Citation26,Citation29].

The risk of TLS requires careful dose escalation and monitoring as well as treatment if it occurs, which may increase the cost on top of venetoclax drug cost. According to a recent study, CLL/SLL-related hospitalizations with a diagnosis of TLS were associated with 39% higher healthcare costs than hospitalizations without a TLS diagnosis [Citation30]. However, the real-world treatment patterns and healthcare costs of patients with CLL/SLL treated with a venetoclax-based regimen remain largely unknown. Therefore, this study sought to assess treatment sequencing, dosing patterns, laboratory testing, and healthcare costs among patients with CLL/SLL treated with venetoclax-based regimens in a US managed care population.

Methods

Data source

Claims from Optum’s de-identified ClinformaticsFootnotei Data Mart Database were used to identify patients initiated on venetoclax-based regimens between 04/11/2016 and 06/30/2019. This database includes claims from both commercial and Medicare Advantage plans for 13 million annual lives in all census regions of the US. It also contains data on patient demographics, dates of eligibility, date of death (month/year), claims for inpatient and outpatient visits, costs of services, and laboratory tests and results.

Data were de-identified and complied with the patient confidentiality requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. As this was an analysis of administrative claims data, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not required, for two reasons: (1) it is a retrospective analysis of existing data (hence no patient intervention or interaction); (2) no patient-identifiable information is included in the claims dataset [Citation31].

Study design

A retrospective longitudinal cohort design was used. To identify the start of the first observed LOT (referred to as 1L), the first claim for an antineoplastic agent after a 12-month washout period without any claims for antineoplastic agents was identified. A window of 28 days was then used to determine all agents included in the 1L treatment regimen, except for patients treated with venetoclax + rituximab, where a window of 90 days was used to make sure the start of rituximab was captured as part of the same LOT, since it is recommended to initiate rituximab following the initial 5-week venetoclax ramp-up period. Each subsequent LOT was defined by the initiation of a new antineoplastic agent that was not part of the prior regimen or re-initiation with the same regimen after a treatment gap of more than 90 days.

The index date was defined as the date of initiation of the first venetoclax-based LOT. For combination regimens, the index date was anchored on the date of initiation of the first agent in the combination. The baseline period was defined as the 12-month period preceding the index date. Study measures were evaluated during the first 60 days of venetoclax therapy (initiation phase) and the subsequent post-initiation phase, with the latter period spanning from day 61 until the initiation of a new LOT, death, end of insurance eligibility, or end of data availability, whichever occurred first. Sixty days were used instead of the 5 weeks recommended for the duration of the ramp-up period [Citation7] to account for potentially longer ramp-up periods and for potential delays between the date of the first claim for venetoclax and the actual treatment start date.

Study population

Patients were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: initiated on venetoclax-based regimen between 04/11/2016 and 06/30/2019 (including venetoclax combination regimens, but excluding investigational combination therapies such as ibrutinib + venetoclax); ≥2 claims with a CLL/SLL diagnosis ≥30 days apart, including ≥1 claim with a CLL/SLL diagnosis prior to the initiation of 1L treatment; ≥18 years old at the index date; ≥12 months of continuous insurance eligibility pre-index date; and ≥30 days of continuous insurance eligibility post-index date. Patients were excluded if they had ≥1 claim with a diagnosis for end-stage renal disease at any time or ≥2 claims with a diagnosis for acute myeloid leukemia ≥30 days apart prior to the initiation of 1L therapy. Patients with end-stage renal disease were excluded because they require dialysis or kidney transplant and often have very high costs, which are not necessarily related to their CLL treatment. Therefore, these patients may skew the results significantly, especially in small sample sizes as in the current study. Additionally, venetoclax should not be used in this population due to the risk for TLS and therefore any patients receiving it would not have been getting customary or standard care. Patients with acute myeloid leukemia were excluded because venetoclax was also approved for the treatment of this disease and the focus of the current study was on patients with CLL/SLL.

Patients were classified into three mutually exclusive cohorts based on when venetoclax-based regimen (either single agent or in combination with other agents) was initiated: the 1L cohort (i.e. the first observed regimen is venetoclax-based), the second-line (2L) cohort (i.e. the second observed regimen is venetoclax-based), and the third- or later-line (3L+) cohort (i.e. the venetoclax-based regimen is observed after at least two prior regimens). Among the 2L cohort, the following subgroups were also considered: 2L venetoclax recipients previously treated with 1L ibrutinib, and 2L venetoclax recipients previously not treated with 1L ibrutinib.

Study measures

For treatment sequencing, the proportion of patients using each type of treatment in observed 1L, 2L and 3L + was reported. For the 3L + cohort, treatment regimens were only described for the subset of patients who received venetoclax as 3L therapy. Venetoclax dosing patterns were also evaluated, including the proportion of patients who used the venetoclax starting pack and the proportion of patients who followed the recommended dosing increase up to 400 mg. In addition, the number of blood and metabolic tests were evaluated and reported per patient per month (PPPM) during the baseline period, the initiation phase, and the post-initiation phase. All-cause healthcare costs (i.e. amounts paid by the plan) during the index venetoclax LOT were evaluated; specifically, costs related to pharmacy claims (including venetoclax and non-venetoclax pharmacy costs), outpatient services, inpatient admissions, emergency room (ER) visits, and other services (i.e. services other than inpatient, outpatient, and ER services received by patients, such as home care, durable medical equipment, and independent laboratory services) were assessed PPPM during the baseline period, the venetoclax initiation phase, and the venetoclax post-initiation phase.

Clinical event-related costs were also evaluated and defined as claims that may be associated with TLS diagnosis, monitoring, prophylaxis, or other clinical events. Monitoring was captured through claims for imaging (ultrasound, computed tomography, and positron emission tomography scans), blood/urine tests (blood: potassium, uric acid, phosphorus, lactate dehydrogenase, calcium, creatinine; urine: creatinine clearance), and other monitoring (claims for enlarged lymph node and hepato or splenomegaly). Prophylaxis was captured through claims for hydration infusions; anti-hyperuricemics including allopurinol, febuxostat, and rasburicase; and G6PD testing. Other clinical events were captured through claims for immunoglobulin treatment, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, infection, renal impairment, hypertension, and cardiac arrhythmia. These health events were selected based on a thorough review of venetoclax prescribing information [Citation7].

Statistical analysis

Given the relatively recent approval of venetoclax, the sample size in each cohort was limited. Therefore, results were descriptive, i.e. means and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables, and frequencies and proportions were reported for categorical variables, and no a priori hypotheses were made. Consequently, the priority in interpreting results was given to clinical meaningfulness assessed with the effect size (i.e. standardized difference [std. diff.] ≥ 10.0%) rather than statistical significance and p-values [Citation32–34] when comparing laboratory testing rates and healthcare costs between the 1L, 2L, and 3L + cohorts and between subgroups of the 2L cohort. Analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

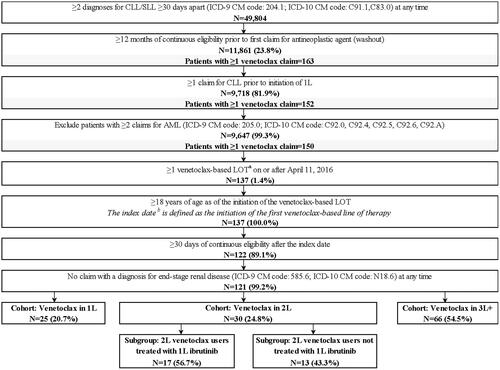

Among a total of 11,861 treated patients with CLL/SLL identified in Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics Data Mart Database, 121 (1.0%) were initiated on a venetoclax-based regimen and met all study selection criteria (). Among these patients, 25 patients had a venetoclax-based regimen as their first observed regimen (1L cohort), 30 patients had a venetoclax-based regimen as their second observed regimen (2L cohort), and 66 patients had a venetoclax-based regimen as their third or later regimen (3L + cohort). Among patients in the 2L cohort, 17 were previously treated with 1L ibrutinib.

Figure 1. Sample selection flowchart. Abbreviations. AML: acute myeloid leukemia; CLL: chronic lymphocytic leukemia; ICD-9 CM: International Classification of Disease, 9th revision, Clinical Modification; ICD-10 CM: International Classification of Disease, 10th revision, Clinical Modification; LOT: line of therapy; SLL: small lymphocytic lymphoma; 1L: first-line; 2L: second-line; 3L+: third- or later-line. (a) Patients with an ibrutinib + venetoclax LOT at any moment were removed from study sample. (b) For patients with more than one line of venetoclax-based therapy, the index date was considered to be the date of the start of the first venetoclax-based LOT.

Of note, only a subset of patients had sufficient observation post-index (i.e. >60 days of follow-up) to be evaluated during the post-initiation phase (1L: N = 20 out of 25, 2L: N = 22 out of 30, 3L+: N = 55 out of 66, 2L venetoclax recipients treated with 1L ibrutinib: N = 12 out of 17, 2L venetoclax recipients not treated with 1L ibrutinib: N = 10 out of 13). Among patients with a post-initiation phase, the median duration of the post-initiation phase was 4.5, 3.1, and 3.4 months for the 1L, 2L, and 3L + cohorts, respectively. Among 2L venetoclax recipients, those who previously received 1L ibrutinib had a median venetoclax post-initiation phase duration of 3.7 months, while those who did not receive ibrutinib in 1L had a median venetoclax post-initiation phase duration of 3.0 months. A minority of patients evaluated during the post-initiation phase progressed to a subsequent regimen: (1L: 3 patients [15.0%], 2L: 7 patients [31.8%], 3L+: 11 [20.0%], 2L venetoclax recipients treated with 1L ibrutinib: 4 patients [33.3%], 2L venetoclax recipients not treated with 1L ibrutinib: 3 patients [30.0%]). The majority of patients who did not progress to a subsequent line of therapy had their regimen end due to the end of data availability (1L: 16 patients [94.1%], 2L: 12 patients [80.0%], 3L: 28 patients [63.6%], 2L venetoclax recipients treated with 1L ibrutinib: 5 patients [62.5%], 2L venetoclax recipients not treated with 1L ibrutinib: 7 patients [100.0%]); the remaining left their managed care plan (1L: 1 patient [5.9%], 2L: 3 patients [20.0%], 3L: 16 patients [36.4%], 2L venetoclax recipients treated with 1L ibrutinib: 3 patients [37.5%], 2L venetoclax recipients not treated with 1L ibrutinib: 0 patients [0.0%]).

Patient baseline characteristics

Patients had a mean age of 72.8 years in the 1L cohort, 70.3 years in the 2L cohort, and 71.8 years in the 3L + cohort (). The proportion of male patients ranged between 64.0% (1L cohort) and 73.3% (2L cohort). The mean Quan-Charlson comorbidity index (Quan-CCI) score was 4.8 for patients in the 1L and 2L cohorts, and 4.6 for those in the 3L + cohort; 16.0% (1L cohort), 40.0% (2L cohort), and 22.7% (3L + cohort) of patients had renal impairment at baseline. The mean number of blood and metabolic tests at baseline was 3.1, 4.4, and 5.6 PPPM in the 1L, 2L, and 3L + cohorts, respectively. The mean total all-cause healthcare costs during baseline were $9006 PPPM (1L cohort), $12,849 PPPM (2L cohort), and $12,704 PPPM (3L + cohort). Among 2L venetoclax recipients, those who previously received 1L ibrutinib had a mean age of 74.0 years and a mean Quan-CCI of 5.1, while those who did not receive ibrutinib in 1L had a mean age of 65.5 years and a mean Quan-CCI of 4.5.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics during the 12-month baseline period prior to the initiation of venetoclax-based therapy.

Treatment sequencing

The mean duration of venetoclax-based treatment (including any treatment-free gaps before the initiation of the next LOT) was 7.7 months in the 1L cohort, 5.5 months in the 2L cohort, and 7.3 months in the 3L + cohort; the mean duration of 2L venetoclax treatment was 5.3 months among patients previously treated with 1L ibrutinib and 5.8 months among patients not previously treated with 1L ibrutinib.

In the 2L and 3L + cohorts (N = 96), 68.8% of patients were treated with ibrutinib before their first venetoclax-based therapy (2L: 56.7%, 3L+: 74.2%). In the 1L, 2L, and 3L + cohorts (N = 121), 8.3% re-initiated venetoclax-based therapy in a subsequent LOT (1L: 8.0%, 2L: 13.3%, 3L+: 6.1%).

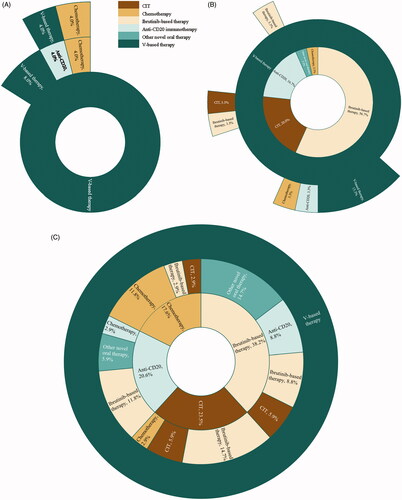

Among patients in the 1L cohort, 13 (52.0%) received venetoclax single agent, and 12 (48.0%) received venetoclax in combination with other agent(s). Four (16.0%) out of 25 patients received 2L therapy, including 2 with venetoclax-based combination therapy, 1 with anti-CD20 immunotherapy, and 1 with chemotherapy (). Among patients in the 2L cohort, 24 (80.0%) received venetoclax single agent and 9 (30.0%) subsequently received 3L therapy, including 4 who initiated another venetoclax-based regimen (). Among recipients of a 3L venetoclax-based regimen (N = 34), 20 (58.8%) received single agent venetoclax. Ibrutinib-based therapy was the most common 1L regimen (13 patients [38.2%]), followed by CIT (8 patients [23.5%]), anti-CD20 immunotherapy (7 patients [20.6%]), and chemotherapy (6 patients [17.6%]). Ibrutinib-based therapy was also the most common 2L regimen in these patients (13 patients [38.2%]; ).

Figure 2. Treatment sequencing among patients who received venetoclax (A) as 1L treatment (N = 25) (B) as 2L treatment (N = 30) and (C) as 3L treatment (N = 34)a. Abbreviations. CIT: chemoimmunotherapy; V: venetoclax; 1L: first-line; 2L: second-line; 3L: third-line. (a) Each concentric ring represents one line of therapy, with the most inner circle representing 1L therapy, the intermediate ring representing 2L therapy, and the outer ring representing 3L therapy.

Dosing patterns

With regard to dosing patterns, the proportion of patients who used the venetoclax starting pack was highest in the 2L cohort (93.3%), followed by the 3L+ (90.9%) and 1L cohorts (72.0%). The 2L cohort had the highest proportion of patients who followed the recommended dosing increase to 400 mg after completing the venetoclax starting pack (75.0%), followed by the 1L and 3L + cohorts (50.0% in each cohort).

Laboratory testing

The mean number of blood and metabolic tests during the initiation and post-initiation phases were 17.2 and 4.6 PPPM (1L cohort), 13.6 and 7.8 PPPM (2L cohort), and 19.5 and 9.2 PPPM (3L + cohort). In the subgroup of 2L venetoclax recipients, the mean number of blood and metabolic tests during the initiation and post-initiation phases was 12.6 and 8.3 PPPM (patients previously treated with 1L ibrutinib) and 14.9 and 7.2 PPPM (patients not previously treated with 1L ibrutinib).

Although statistical testing was not conducted due to the small sample size, patients in the 2L cohort appeared to have a lower mean number of blood and metabolic tests during the initiation phase than those in the 1L cohort (13.6 versus 17.2 PPPM), while those in the 3L + cohort had higher mean number of tests (19.5 PPPM; all std. diff. ≥10.0%). Relative to patients in the 1L cohort (4.6 PPPM), those in the 2L (7.8 PPPM) and 3L+ (9.2 PPPM) cohorts appeared to have higher mean monthly number of blood and metabolic tests during the post-initiation phase (all std. diff. ≥10.0%). The mean monthly number of blood and metabolic testing during the initiation phase appeared to be lower among 2L venetoclax recipients previously treated with 1L ibrutinib than those not previously treated with 1L ibrutinib (12.6 versus 14.9 PPPM; std. diff. ≥10.0%; Tables S1 and S2).

Healthcare costs

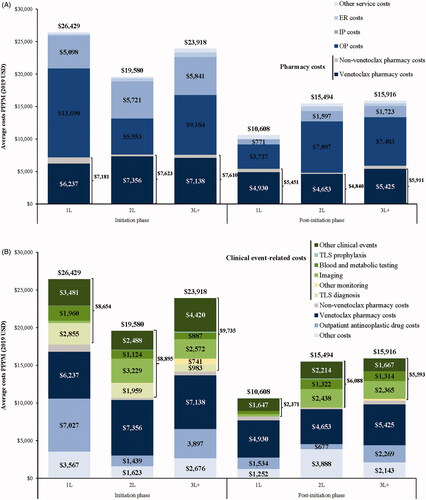

Mean total all-cause healthcare costs during the venetoclax initiation and post-initiation phases were $26,429 and $10,608 PPPM (1L cohort), $19,580 and $15,494 PPPM (2L cohort), and $23,918 and $15,916 PPPM (3L + cohort; and Tables S1 and S2). Although statistical testing was not conducted due to the small sample size, mean total all-cause healthcare costs incurred during the venetoclax initiation phase appeared to be lower in the 2L and 3L + cohorts relative to the 1L cohort (all std. diff. ≥10.0%). Differences in mean total all-cause healthcare costs were primarily driven by treatment costs (including pharmacy and outpatient antineoplastic drug costs) during the initiation phase (1L: $14,208 PPPM, 2L: $9062 PPPM, 3L+: $11,507 PPPM; and Tables S1 and S2). More specifically, mean total pharmacy costs [venetoclax pharmacy costs] during the venetoclax initiation and post-initiation phases were $7181 [$6237] and $5451 [$4930] PPPM (1L cohort), $7623 [$7356] and $4840 [$4653] PPPM (2L cohort), and $7610 [$7138] and $5911 [$5425] PPPM (3L + cohort; and Table S1). Among the 2L cohort, mean total pharmacy costs [venetoclax pharmacy costs] during the 2L venetoclax initiation and post-initiation phases were $7712 [$7485] and $4767 [$4514] PPPM (patients previously treated with 1L ibrutinib) and $7508 [$7186] and $4929 [$4819] PPPM (patients not previously treated with 1L ibrutinib; and Table S2).

Figure 3. (A) All-cause healthcare costs by place of service among 1L, 2L, and 3L + venetoclax recipients, (B) all-cause healthcare costs by clinical event among 1L, 2L, and 3L + venetoclax recipients, (C) all-cause healthcare costs by place of service among 2L venetoclax recipients treated or not treated with ibrutinib in 1L, and (D) all-cause healthcare costs by clinical event among 2L venetoclax treated or not treated with ibrutinib in 1L. Abbreviations. ER: emergency room; IP: inpatient; OP: outpatient; PPPM: per patient per month; TLS: tumor lysis syndrome; USD: United States dollars; 1L: first-line; 2L: second-line; 3L+: third- or later-line.

Mean total clinical event-related costs during the venetoclax initiation and post-initiation phases were $8654 and $2371 PPPM (1L cohort), $8895 and $6088 PPPM (2L cohort), and $9735 and $5593 PPPM (3L + cohort; and Tables S1 and S2). Although statistical testing was not conducted due to the small sample size, mean total clinical event-related costs incurred during the initiation phase appeared to be similar between the 1L cohort and the 2L or 3L + cohorts (all std. diff. <10.0%). During the venetoclax initiation phase, patients in the 1L cohort appeared to incur higher mean TLS diagnosis costs than those in the 3L + cohort (mean: $2855 versus $983 PPPM, std. diff. ≥10.0%). Mean TLS diagnosis costs were null or near zero during the venetoclax post-initiation phase across all LOT cohorts. Higher mean imaging costs were observed in the 2L (initiation phase: $3229 PPPM, post-initiation phase: $2438 PPPM) and 3L + cohorts (initiation phase: $2572 PPPM, post-initiation phase: $2365 PPPM) relative to the 1L cohort (initiation phase: $307 PPPM, post-initiation phase: $314 PPPM; all std. diff. ≥10.0%).

Although statistical testing was not conducted due to the small sample size, mean total all-cause healthcare costs during both the venetoclax initiation and post-initiation phases appeared to be lower among 2L venetoclax recipients previously treated with 1L ibrutinib relative to 2L venetoclax recipients not previously treated with 1L ibrutinib (initiation phase: $15,506 versus $24,908 PPPM; post-initiation phase: $14,318 versus $16,905 PPPM; all std. diff. ≥10.0%; and Tables S1 and S2). In addition, mean total clinical event-related costs during both the venetoclax initiation and post-initiation phases appeared to be lower among 2L venetoclax recipients previously treated with 1L ibrutinib relative to 2L venetoclax recipients not previously treated with 1L ibrutinib (initiation phase: $6368 versus $12,198 PPPM; post-initiation phase: $5273 versus $7066 PPPM; all std. diff. ≥10.0%; and Tables S1 and S2). During the venetoclax initiation phase, 2L venetoclax recipients previously treated with 1L ibrutinib appeared to have lower mean TLS diagnosis costs ($1222 versus $2924 PPPM, std. diff. ≥10.0%) and costs related to other clinical events ($1170 versus $4210 PPPM, std. diff. ≥10.0%) than 2L venetoclax recipients not previously treated with 1L ibrutinib.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of patients with CLL/SLL treated with venetoclax as a single agent or in combination therapy, the analysis of treatment sequencing showed that the most common sequence observed was ibrutinib followed by venetoclax. Following the first venetoclax-based LOT, a substantial proportion of patients re-initiated venetoclax in a subsequent LOT, indicating potential treatment disruption with venetoclax in the real-world given the limited duration of treatment observed for each LOT in the current study [Citation35], which was lower than what was observed in venetoclax clinical trials [Citation15–26].

Moreover, during the venetoclax index LOT, the mean number of blood and metabolic tests performed during the 60-day venetoclax treatment initiation phase was higher than during the post-initiation phase, which is consistent with the risk of TLS being highest during the ramp-up period. This observation is also consistent with the prescribing information of venetoclax, which recommends to increase the frequency of blood chemistry monitoring and consider hospitalization in patients with a high tumor burden, or in those with a medium tumor burden and a creatinine clearance rate <80 ml/min (patients are considered as having normal renal function when their creatinine clearance rate is ≥80 ml/min) [Citation7].

A real-world study by Mato et al. found that compliance with TLS prophylaxis measures was excellent among venetoclax recipients with CLL/SLL [Citation28]. Yet, Mato et al. also found that TLS occurred in 13% of CLL/SLL patients treated with venetoclax (18 patients had laboratory TLS, of whom 6 had clinical TLS). Koelher et al. reported a similar proportion of patients with TLS (13%; 6 patients had laboratory TLS, of whom 3 had clinical TLS) among patients treated with venetoclax in routine clinical practice [Citation36]. These proportions are considerably higher than the values reported in clinical trials (∼2%) [Citation15,Citation17,Citation20,Citation22,Citation25] (see Table S3 for a summary of clinical and real-world studies reporting TLS rates). While TLS risk (i.e. tumor burden) could not be assessed with claims to determine how risk status compares to clinical trials, it was observed that 16.0–40.0% of patients included in the current study had baseline renal impairment, which is a major risk factor for TLS [Citation27]. Therefore, it is likely that part of the discrepancy between the incidence of TLS reported in the real world and that reported in prior clinical studies of venetoclax can be attributed to the presence of additional TLS risk factors in real-world patient populations, such as a higher proportion of patients with renal impairment, resulting in potentially higher proportion of patients at high risk for TLS [Citation37].

In the current study, the mean number of blood and metabolic tests, total all-cause healthcare costs, and clinical event-related costs (including TLS diagnosis costs) during the 60-day venetoclax treatment initiation phase were higher than during the subsequent post-initiation phase for all cohorts. This is expected given the need to monitor and treat TLS during this timeframe and the decrease in required testing and lower risk of TLS after the initiation phase.

Our study also provides evidence that patients treated with ibrutinib prior to venetoclax may have lower all-cause and clinical event-related healthcare costs during venetoclax initiation phase than those who did not receive ibrutinib previously. This observation may be a consequence of patients initiating venetoclax shortly after ibrutinib discontinuation, to avoid potential rapid tumor flare associated with discontinuation [Citation38]. To mitigate this risk, treating physicians may attempt to minimize the gap between an ibrutinib-based LOT and a subsequent LOT, so that patients may initiate their next LOT with a lower disease burden. This lower disease burden also implies a reduced risk of TLS at the time of initiating venetoclax therapy, which may lower the use of intensive care measures. Indeed, rigorous TLS prevention protocols (including prophylaxis and TLS risk stratification) should be considered as potential strategies to reduce the incidence of TLS, and more intensive measures – including hospitalization – can be necessary as TLS risk increases [Citation7,Citation39] Therefore, the decision to use ibrutinib before the initiation of venetoclax treatment should be clinically driven based on the information available to the treating physician. It should also be noted that the lower costs observed in the current study during venetoclax treatment following the use of ibrutinib do not take into account the costs associated with the previous use of ibrutinib.

The fact that ibrutinib was approved before venetoclax, may also partially explain the high proportion of patients who used ibrutinib prior to venetoclax in the current study. Indeed, more than half of 2L (56.7%) and 3L+ (74.2%) venetoclax recipients had previously received ibrutinib. With additional follow-up and sample size allowing for the inclusion of more patients treated with newly approved venetoclax combinations in earlier LOTs (including venetoclax + obinutuzumab in 1L), future studies comparing cohorts of patients treated with 1L ibrutinib prior to 2L venetoclax and patients treated with 1L venetoclax prior to 2L ibrutinib will help understand how treatment sequencing of ibrutinib and venetoclax can affect patient outcomes.

Limitations

The present study is subject to some limitations. First, this study was descriptive in nature due to limited sample size; therefore, adjustments for differences in patient characteristics between cohorts could not be performed. However, results reported in the current study can help inform future comparative analyses of outcomes between treatment sequences or between earlier and later venetoclax LOTs, adjusting for potential confounders such as disease severity and/or mutation status (which could not be evaluated with the current data). Second, results of this study may not be generalizable to all patients with CLL/SLL, since only a limited number of managed care patients were included. Third, claims data may contain omissions and inaccuracies, including the fact that a claim may not imply that a given medication was immediately taken as prescribed, which may lead to inaccuracies in assessments of dosing patterns and gaps in treatment. However, this is expected to equally affect all cohorts and should have no impact on the overarching conclusions of this study. Fourth, the reason for switching or re-initiating treatment was not available in this claims data; therefore, LOT identification was based on observed claims and not on patients’ response to treatment. Fifth, despite the use of a 12-month washout period to ascertain the identification of 1L therapy, some patients in remission for an extended period of time may have been inadvertently included; therefore, LOT number may not have been appropriately identified in these patients, resulting in potential differences between observed 1L therapy and true 1L therapy, especially since the data available for the analysis (04/11/2016–06/30/2019) was mostly before the approval of venetoclax in 1L in combination with obinutuzumab (05/15/2019). Lastly, due to venetoclax being recently approved for treatment in CLL patients (04/11/2016), the observation period was limited; therefore, not all patients had at least 60 days of treatment and could be observed during the post-initiation phase. Furthermore, the entire post-initiation phase may not have been captured for patients who had an observable post-initiation phase. In addition, since data available for this study captured less than two months during which venetoclax was approved in combination with obinutuzumab as 1L therapy (from 05/15/2019 to 06/30/2019), results should be interpreted in the context of the use of venetoclax largely prior to its approval in combination with obinutuzumab. Future studies with longer observation periods will allow to capture more CLL patients treated with venetoclax (including more patients treated with venetoclax + obinutuzumab in 1L), thus allowing for adjusted statistical comparisons.

Conclusions

In this descriptive study of patients with CLL/SLL treated with venetoclax-based regimens, ibrutinib followed by venetoclax was the most common treatment sequence among venetoclax recipients who had at least one previous observed regimen. Furthermore, mean laboratory testing rates, all-cause healthcare costs, and clinical event-related costs were the highest during the first 60 days of venetoclax treatment, overlapping with the required dose ramp-up period for TLS risk management. During the venetoclax initiation phase, patients for whom venetoclax was the first observed regimen had higher mean all-cause healthcare costs than those who were treated with venetoclax after a previous regimen. In addition, venetoclax recipients previously treated with ibrutinib incurred lower mean all-cause and – in particular – clinical event-related (including TLS diagnosis) costs than venetoclax recipients not previously treated with ibrutinib, suggesting pre-treatment with ibrutinib may reduce costs associated with subsequent venetoclax treatment.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The sponsor was involved in all steps of the present work, including the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

K.A.R. reports the following disclosures: research funding from Genentech, AbbVie, Novartis, and Janssen (not for the present study), consulting for Acerta Pharma, AstraZeneca, Innate Pharma, Pharmacyclics, Genentech, and AbbVie, and travel funding from AstraZeneca. B.E., A.M.M., F.K., M.H.L., and P.L. are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript. Q.H. is an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. and stockholder of Johnson & Johnson. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from CMRO for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Previous presentation

Part of the material in this manuscript was accepted as an abstract for the 2020 ASCO Annual Meeting, held 29 May–2 June 2020.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (51.6 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Samuel Rochette and Loraine Georgy, employees of Analysis Group, Inc. The authors would also like to acknowledge Kay Sadik, Zhongyun Zhao, and Sarah Lamberth from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC for contributing to the interpretation of the results and for providing critical comments over the course of the study.

Notes

i Optum Clinformatics, Eden Prairie, MN, USA.

References

- Hallek M, Shanafelt TD, Eichhorst B. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Lancet. 2018;391(10129):1524–1537.

- Kipps TJ, Stevenson FK, Wu CJ, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:16096.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA A Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30.

- Matasar MJ, Dacosta Byfield S, Blauer-Peterson C, et al. Real-world health care utilization and costs among patients newly initiating systemic therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in the United States. Blood. 2016;128(22): 5928.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing Information – CALQUENCE (acalabrutinib). Accesssed on April 17 2020. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/210259s006s007lbl.pdf.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing Information – IMBRUVICA (ibrutinib). Accesssed on April 17 2020. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/205552s029,210563s004lbl.pdf.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing Information – VENCLEXTA (venetoclax) (Revised 05/2019). Accesssed on April 17 2020. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/208573s011s014s015lbl.pdf.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing Information – ZYDELIG (idelalisib). Accesssed on April 17 2020. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/205858s013lbl.pdf.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing Information – GAZYVA (obinutuzumab). Accesssed on April 17 2020. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/125486s025lbl.pdf.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing Information – COPIKTRA (duvelisib). Accesssed on April 17 2020. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/211155s001lbl.pdf.

- Burger JA, Barr PM, Robak T, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with CLL/SLL: 5 years of follow-up from the phase 3 RESONATE-2 study. Leukemia. 2020;34(3):787–798.

- Byrd JC, Hillmen P, O’Brien S, et al. Long-term follow-up of the RESONATE phase 3 trial of ibrutinib vs ofatumumab. Blood. 2019;133(19):2031–2042.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing Information – VENCLEXTA (venetoclax) (Revised 04/2016). Accesssed on April 17 2020. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/208573s000lbl.pdf.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing Information – VENCLEXTA (venetoclax) (Revised 06/2018). Accesssed on April 17 2020. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/208573s004s005lbl.pdf.

- Jones JA, Mato AR, Wierda WG, et al. Venetoclax for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia progressing after ibrutinib: an interim analysis of a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(1):65–75.

- Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, et al. Targeting BCL2 with venetoclax in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):311–322.

- Rogers KA, Huang Y, Ruppert AS, et al. Phase 1b study of obinutuzumab, ibrutinib, and venetoclax in relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2018;132(15):1568–1572.

- Stilgenbauer S, Eichhorst B, Schetelig J, et al. Venetoclax in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(6):768–778.

- Stilgenbauer S, Eichhorst B, Schetelig J, et al. Venetoclax for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia with 17p deletion: results from the full population of a phase II pivotal trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(19):1973–1980.

- Cramer P, von Tresckow J, Bahlo J, et al. Bendamustine followed by obinutuzumab and venetoclax in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL2-BAG): primary endpoint analysis of a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(9):1215–1228.

- Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Fink AM, et al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2017;129(19):2702–2705.

- Flinn IW, Gribben JG, Dyer MJS, et al. Phase 1b study of venetoclax-obinutuzumab in previously untreated and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2019;133(26):2765–2775.

- de Vos S, Swinnen LJ, Wang D, et al. Venetoclax, bendamustine, and rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory NHL: a phase Ib dose-finding study. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(9):1932–1938.

- Kater AP, Seymour JF, Hillmen P, et al. Fixed duration of venetoclax-rituximab in relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia eradicates minimal residual disease and prolongs survival: post-treatment follow-up of the MURANO phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(4):269–277.

- Seymour JF, Kipps TJ, Eichhorst B, et al. Venetoclax-rituximab in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1107–1120.

- Jain N, Keating M, Thompson P, et al. Ibrutinib and venetoclax for first-line treatment of CLL. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(22):2095–2103.

- Tambaro FP, Wierda WG. Tumour lysis syndrome in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia treated with BCL-2 inhibitors: risk factors, prophylaxis, and treatment recommendations. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(2):e168–e176.

- Mato AR, Thompson M, Allan JN, et al. Real-world outcomes and management strategies for venetoclax-treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients in the United States. Haematologica. 2018;103(9):1511–1517.

- Wierda WG, James DF, Ninomoto J, et al. Ibrutinib (Ibr) plus venetoclax (Ven) for first-line treatment of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (SLL): results from the MRD cohort of the phase 2 CAPTIVATE study. Blood. 2019;134(Suppl 1):35–35.

- Aroke H, Cirincione A, Kogut S. Length of stay, hospitalization cost, and in-hospital mortality associated with tumor lysis syndrome among patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Value in Health. 2018;21 (Suppl 1):S23–S24.

- Department of Health and Human Services. 45 CFR Subtitle A. Accesssed on January 7, 2021. Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2016-title45-vol1/pdf/CFR-2016-title45-vol1-part46.pdf.

- Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat – Simul Comput. 2009;38(6):1228–1234.

- Sullivan GM, Feinn R. Using effect size-or why the P value is not enough. J Graduate Med Educ. 2012;4(3):279–282.

- Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. The ASA statement on p-values: context, process, and purpose. Am Statistician. 2016;70(2):129–133.

- Kabadi SM, Goyal RK, Nagar SP, et al. Treatment patterns, adverse events, and economic burden in a privately insured population of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the United States. Cancer Med. 2019;8(8):3803–3810.

- Koehler AB, Leung N, Call TG, et al. Incidence and risk of tumor lysis syndrome in patients with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) treated with venetoclax in routine clinical practice. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61(10):2383–2388.

- Mato AR. Predicting TLS in venetoclax-treated CLL patients. Video J Hematol Oncol. 2019;25:4264–4270.

- Hampel PJ, Ding W, Call TG, et al. Rapid disease progression following discontinuation of ibrutinib in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated in routine clinical practice. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60(11):2712–2719.

- Anderson MA, Seymour JF. Tumor lysis syndrome: still the Achilles heel of venetoclax in treatment of CLL? Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61(10):2286–2283.