Abstract

Introduction

Individuals with bipolar depression often experience functional impairment that interferes with recovery. These analyses examined the effects of cariprazine on functional outcomes in patients with bipolar I disorder.

Methods

Prespecified analyses of data from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pivotal trial of cariprazine in bipolar I depression (NCT01396447) evaluated mean changes from baseline to week 8 in Functional Assessment Short Test (FAST) total score. Post hoc analyses with no adjustment for multiplicity evaluated FAST subscale scores, functional recovery and remission (FAST total score ≤11 and ≤20, respectively), and 30% or 50% improvement from baseline.

Results

There were 393 patients with bipolar I disorder (placebo = 132; cariprazine: 1.5 mg/d = 135, 3 mg/d = 126) in the FAST analysis population. Statistically significant differences were noted for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d versus placebo in mean change from baseline in FAST total score (p<.01) and on 5 of 6 subscale scores (p<.05); cariprazine 3 mg/d was significantly different than placebo on the Interpersonal Relationship subscale (p<.05). Rates of functional remission and recovery, and ≥30% or ≥50% improvement were significantly greater for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d versus placebo (p<.05 all); the percentage of patients with ≥30% improvement was significantly different for cariprazine 3 mg/d versus placebo (p<.05).

Conclusion

At week 8, statistically significant improvements in FAST outcomes were observed for cariprazine versus placebo in patients with bipolar I depression; more consistent results were noted for 1.5 mg/d than 3 mg/d. In addition to improving bipolar depression symptoms, these results suggest that cariprazine may improve functional outcomes.

Introduction

Bipolar I disorder is a serious and chronic mental disorder that is characterized by manic, depressive, and mixed mood episodes that are often accompanied by substantial functional impairment and reduced quality of lifeCitation1. Even between mood episodes, up to 60% of patients do not regain full social or occupational functioningCitation2, illustrating how functional recovery often lags behind remission of symptomsCitation3–7. Additionally, several clinical characteristics, including previous mixed episodes, subthreshold depressive symptoms, previous hospitalizations, and older age have been identified as factors that significantly contribute to overall poor functioning in bipolar disorderCitation8. Compared to manic symptoms, depressive symptoms are associated with greater social, familial, and occupational impairmentsCitation9–11; since a greater proportion of time is spent ill with depressive symptoms than with manic or mixed symptomsCitation1, patients with bipolar depression are especially vulnerable to problems across functional domains. In a national survey, 87% of patients with bipolar disorder and a past-year major depressive episode reported severe role impairment; in comparison, 57% of respondents with a past-year manic/hypomanic episode reported severe role impairmentCitation12. Further, in a global survey of individuals with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, people with bipolar disorder identified insufficient treatment of depressive symptoms and functioning/quality-of-life issues among their 3 top unmet treatment needsCitation13. Although the relationship between symptomatic and functional improvement is not fully understood, the substantial burden of illness associated with bipolar depression mandates that treatment should be collectively focused on functional recovery as well as symptom remission.

Poor functioning is a key driver of disability in patients with bipolar disorderCitation14, which is among the top 10 leading causes of worldwide disability for young adultsCitation15. Depressive symptoms are the most prominent factor associated with functional impairment in bipolar disorderCitation4,Citation5,Citation9,Citation11,Citation16–20, and although patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) also experience functional impairment, it is more severe in patients with bipolar disorder, as seen in higher rates of nonemployment and greater deficiencies in areas of social, household, and cognitive functioningCitation21–24. Importantly, neurocognitive impairment, which is a core feature of bipolar disorder, has also been increasingly recognized as a factor related to functional disability, with both cross-sectional and long-term studies reporting a link between cognitive impairment and disability in euthymic bipolar disorder patientsCitation9,Citation25,Citation26. Further, a link between impaired functioning and childhood abuse and maltreatment in individuals with psychiatric disorders, including bipolar disorder, has been suggested by an increased risk for self-injury and suicidal behavior, suggesting that negative preliminary life experiences may set the stage for subsequent functional difficultiesCitation27.

Although no consensus definition for psychosocial functioning exists, some recommend that the concept should include diverse behavioral domains, such as social function, occupational function, ability to live independently, and capacity for romance, recreation, and studyCitation6. As such, it is important that outcomes are measured across a range of domains since patients may function differently in different areas and recovery is described as the ability to function at a comparable level to what was actualized before the most recent prior episodeCitation28. This study utilizes the Functional Assessment Short Test (FAST)Citation7,Citation17, which is a validated 24-item clinician-rated scale that was designed to measure the areas of functional difficulty associated with bipolar disorder. The FAST is commonly used to assess functioning in bipolar disorder clinical trialsCitation29, with overall functioning and specific behavioral domains assessed via FAST total score and 6 subscales. Showing strong psychometric properties (e.g. internal consistency, concurrent validity, discriminant validity, test-retest reliability), the FAST was sensitive to different mood states (mania/hypomania, depression, or euthymia) in patients with bipolar disorderCitation7,Citation17. Items are measured according to levels of disability (from none to severe) and higher scores indicate more severe disability in specific areas of functioning that are commonly problematic for patients with bipolar disorder (e.g. problem solving, work, living alone, maintaining friendships, sexual relations)Citation7. Developed in consideration of the unique nuances and specific functional deficits associated with bipolar disorder, the FAST Scale may be considered the best instrument for measuring functional impairments in bipolar disorderCitation7.

Cariprazine is a dopamine D3-preferring D3/D2 receptor partial agonist with serotonin 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist properties that is approved to treat adult patients with acute mixed/manic (3–6 mg/d) and depressive (1.5 and 3 mg/d) episodes associated with bipolar I disorder. The efficacy of cariprazine in bipolar depression was demonstrated in one phase 2 b and two phase 3 fixed-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialsCitation30–32 where the primary efficacy parameter was change from baseline to week 6 in Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total scoreCitation33. The dopamine D3 receptor partial agonist characteristic of cariprazine is hypothesized to have potential benefits on neural pathways involved in both depressive and cognitive symptoms, which could lessen functional impairment. To explore this, we used data from the phase 2 b pivotal registration trialCitation30, which included the FAST as a prespecified additional efficacy measure and allowed us to investigate the effect of cariprazine on functioning in patients with bipolar depression.

Methods

Study design

This multinational, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, fixed-dose study included adult patients with bipolar I disorder and a current major depressive episode (NCT01396447); detailed methods of this study have been publishedCitation30. Briefly, the study consisted of a screening period of up to 14 days, 8-weeks of double-blind treatment, and a 1-week safety follow-up; per local clinical practice, patients could be hospitalized during screening and for up to 2 weeks of double-blind treatment. Patients were randomized (1:1:1:1) to placebo or cariprazine 0.75, 1.5, or 3 mg/d. All cariprazine patients initiated treatment at 0.5 mg/d, with dosage increased to 0.75 mg/d on day 3; in the 1.5 and 3 mg/d groups, dosage was increased to 1 mg and 1.5 mg on days 5 and 8, respectively, and in the 3 mg/d group, dosage was increased to 3 mg on day 15. Double-blind treatment was 8 weeks in duration, with the primary efficacy parameter (MADRS change from baseline) assessed at week 6 and FAST outcomes assessed at week 8 per the study protocol.

Male and female patients (18–65 years) met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria (in use at the time of the study) for bipolar I disorder without psychotic featuresCitation34, with a previously verified manic or mixed episode and a current major depressive episode ≥4 weeks’ and ≤12 months’ duration; patients with bipolar II disorder were not included in the primary study. Clinical inclusion criteria included a 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD17)Citation35 total score ≥20 and Item 1 (depressed mood) score ≥2, and a Clinical Global Impressions-Severity (CGI-S) score ≥4Citation36. Patients were excluded from participation if they had a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score >10Citation37, a principal DSM-IV-TR axis I diagnosis other than bipolar disorder, or 4 or more mood state episodes (i.e. depressive, manic, hypomanic, mixed) within 12 months before screening. Additionally, alcohol- or substance-related disorders (within 6 months), risk for suicide (investigator judged or rating scale assessment), and nonresponse to 2 or more treatment trials (adequate dose and duration) of an approved bipolar depression agent in the current depressive episode were exclusionary.

Outcome measures and statistical analysis

The 24-item FAST scale was administered at baseline and at week 8. The 6 subscales of the FAST assess specific areas of functioning, with items rated on a 4-point scale from 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty): Autonomy (4 items), Occupational Functioning (5 items), Cognitive Functioning (5 items), Financial Issues (2 items), Interpersonal Relationships (6 items), and Leisure Time (2 items). The FAST total score (range, 0–72) is calculated as the sum of each of the 24 item scores, with higher scores representing worse functionCitation7,Citation17. If more than 3 item scores were missing, the total score was set to missing; if any subscale item scores were missing, the subscale score was set to missing while the total score was calculated as the sum of each of the non-missing item scores.

Data were analyzed in 1.5 or 3 mg/d dose groups; since the 0.75 mg/d dose is outside the recommended dose range, it was not included in these analyses. FAST outcomes were analyzed in the modified intent-to-treat population (mITT; all patients in the safety population who had baseline and postbaseline FAST score assessments). Outcomes of interest were mean changes from baseline to week 8 in FAST total score (prespecified efficacy measure) and FAST subscales scores. In the original study, the analysis of LS mean change in FAST total score (and p values) was a prespecified additional efficacy measure, and analysis of mean changes in FAST subscale scores with descriptive statistics (no testing of p values) were also prespecified; inferential statistics were performed as post hoc analysis. Prespecified and post hoc FAST analyses were performed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with treatment group and pooled study center as factors and baseline FAST score value as a covariate. Last observation carried forward (LOCF) was used for imputation of data in cases where patients included in the FAST analysis population discontinued the study prior to week 8 and had a second FAST assessment at an early termination visit. p Values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons because these analyses were post hoc and exploratory in nature; in this type of analysis, adjustment for multiple comparisons is less practical and results could be misleadingCitation38.

Additional post hoc analyses were conducted to determine the percentage of patients who achieved functional remission (defined as a FAST total score of ≤20) and functional recovery (defined as a FAST total score ≤11) at week 8. These cut-off scores delineating clinically meaningful functional remission and recovery (Bonnín et al. 2018) were based on empirically determined FAST score categories of impairment severity (no impairment = 0–11; mild impairment = 12–20; moderate impairment = 21–40; severe impairment >40)Citation39. The percentage of patients who achieved ≥30% and ≥50% improvement in FAST total score versus the baseline value was also evaluatedCitation40. These responder analyses were analyzed by logistic regression with the placebo as the reference, and treatment group and corresponding baseline value as explanatory variables.

The study protocol complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines; written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Results

A total of 393 patients (placebo = 132; cariprazine: 1.5 mg/d = 135, 3 mg/d = 126) were included in the mITT population for FAST analyses; FAST total score could not be calculated in 5 patients due to missing FAST item scores. As expected based on the study’s entry criteria, mean MADRS (∼30) and HAMD17 (∼24) total scores at baseline indicated a population with at least moderate depressionCitation41. Mean FAST total score at baseline (∼39) indicated moderate-to-severe functional impairment ()Citation39. The vast majority of cariprazine-treated patients had moderate or severe functional impairment at baseline (no impairment [total score <12] = 11; mild impairment [total score 12–20] = 20; moderate impairment [total score 21–40] = 121; severe impairment [total score >40] = 136). The most severe baseline impairment was noted in the domains of occupational functioning, interpersonal relationships, and cognitive functioning; the least severe baseline impairment was seen in the area of financial issues.

Table 1. Baseline efficacy scores and functional impairment.

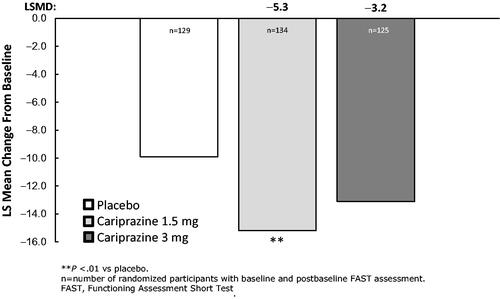

The least squares mean difference (LSMD) in FAST total score change from baseline to week 8 was statically significant in favor of cariprazine 1.5 mg/d versus placebo (p=.0051); numerical improvement was noted for cariprazine 3 mg/d versus placebo but the difference was not statistically significant (p=.0575) ().

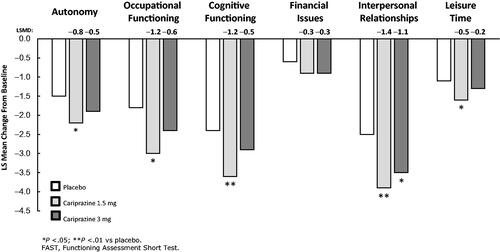

On the FAST subscales, the LSMD versus placebo was statistically significant in favor of cariprazine 1.5 mg/d for Autonomy, Occupational Functioning, Cognitive Functioning, and Leisure Time; on the Interpersonal Relationships subscale, the difference versus placebo was statistically significant for both cariprazine 1.5 and 3 mg/d (). Nonsignificant numerical improvement was noted on the Financial Issues subscale for both cariprazine doses.

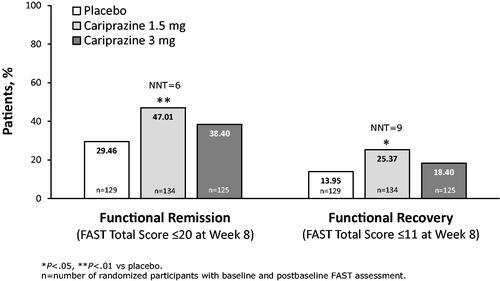

A significantly greater percentage of cariprazine 1.5 mg/d patients versus placebo patients achieved functional remission defined as a FAST total score ≤20 at week 8; the number needed to treat (NNT) indicated that 6 patients would need to be treated with cariprazine to achieve one additional outcome of remission versus placebo (). When the more stringent outcome of functional recovery (FAST total score ≤11 at week 8) was examined, a significantly greater percentage of cariprazine 1.5 mg/d patients also achieved this outcome versus placebo, with an NNT of 9 ().

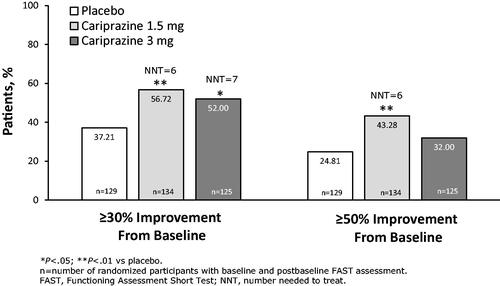

When response was evaluated using a threshold of ≥30% improvement from FAST total score at baseline, more than half of patients treated with cariprazine 1.5 and 3 mg/d achieved response, which was a significantly greater percentage for both cariprazine doses versus placebo; the NNTs were 6 and 7 for 1.5 and 3 mg/d, respectively (). Using the ≥50% improvement from baseline threshold, a greater percentage of patients treated with cariprazine 1.5 mg/d versus placebo again achieved response (NNT = 6); the percentage of patients with ≥50% improvement was numerically greater for cariprazine 3 mg/d versus placebo but the difference was not significant ().

Discussion

Even after remission of depressive symptoms, many patients with bipolar depression fail to achieve functional recovery, with impairment and reduced quality of life persisting during periods of euthymia despite adequate treatmentCitation42. In these analyses, patients with symptomatic bipolar I depression who were treated with cariprazine had significantly greater functional improvement across outcomes measured by the FAST than did patients treated with placebo. Namely, the differences in change from baseline in FAST total score and on 5 of 6 subscale scores were statistically significant for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d versus placebo, suggesting comprehensive improvement in functioning for this cariprazine dose. Beyond mean score changes, clinically relevant improvement was demonstrated by cariprazine 1.5 mg/d across measures of functional response, remission, and recovery, suggesting that cariprazine treatment played a role in restoring patient health and functioning. Of note, cariprazine 1.5 mg/d was consistently more effective than cariprazine 3 mg/d across FAST outcomes, suggesting a potential advantage for the lower dose in some patients.

Functional improvement characterized by changes in specific behavioral domains was evaluated by change from baseline on the subscales of the FAST. Across subscales measuring Autonomy, Occupational Functioning, Cognitive Functioning, and Leisure Time, statistically significant differences versus placebo were detected for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d; both cariprazine 1.5 and 3 mg/d were significantly different than placebo on the Interpersonal Relationships subscale. Numerical improvements without a significant difference from placebo were also seen for both cariprazine doses on the Financial Issues subscale, with mild baseline impairment in this domain potentially contributing to the lack of significant difference from placebo on this subscale. These results suggest that cariprazine-related improvement was seen across the functional areas of daily living that are relevant to recovery, including social functioning (i.e. maintaining interpersonal relationships, participating in social activities), occupational functioning (i.e. holding down a job, accomplishing responsibilities), and independent living (i.e. living on your own, taking care of yourself). Importantly, the FAST also assesses cognitive functioning, which is considered a therapeutic target to help improve functional outcomes in patients with bipolar disorder since cognitive deficits are experienced by 40%–60% of patientsCitation43. In this post hoc analysis, significant improvement in cognitive function was noted for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d versus placebo, suggesting treatment effects in cognitive areas that may be related to functional outcomes in bipolar disorder (e.g. verbal memory, attention, executive function)Citation9,Citation18,Citation25,Citation26,Citation44.

Rating scale-based response, remission, and recovery are commonly measured clinical trial outcomes in bipolar disorder, although empirical consensus definitions are lackingCitation45. In general terms, remission is generally conceptualized as the virtual lack of symptoms, while recovery is a far reaching concept that incorporates symptomatic remission, functional recovery, prevention of relapse or recurrence, and improved subjective quality of lifeCitation46. Researchers have emphasized the importance of recovery and the return to wellness as the most important outcome for patients with bipolar disorderCitation47. To enhance the relevance of our analysis, empirically evaluated and clinically meaningful cut-offs defined by Bonnin et al. were used to define mild, moderate, and severe functional impairment and functional recovery, remission, and improvementCitation39. Since functioning is not a static state and patients can improve with effective pharmacological or psychological intervention, it is useful to quantify functional remission and recovery in terms of decreased FAST total score and the corresponding downward flow into progressively less severe impairment categories (i.e. from severe, to moderate, to mild, to no impairment)Citation36. In our post hoc analysis, almost one half of cariprazine 1.5 mg/d patients (47%) and 38% of cariprazine 3 mg/d patients achieved functional remission (FAST total score ≤20 at week 8), suggesting that 43% of cariprazine-treated patients overall had only mild signs of impairment or better at the end of treatment. When the more stringent category of functional recovery (FAST total score ≤11 at week 8) was evaluated, 25% and 18% of cariprazine 1.5 mg/d and 3 mg/d patients, respectively, achieved this threshold, further suggesting that 22% overall had no impairment at the end of treatment. Given that our study population had moderate-to-severe functional impairment at baseline, the percentage of patients reaching these thresholds likely means that many patients achieved clinically meaningful improvement.

Further, improvement from baseline can also be evaluated by less stringent outcomes, including response. The traditional rating scale definition of response in clinical studies of depressive symptoms is ≥50% improvement from baselineCitation40, while partial response is defined as 30%–50% improvementCitation48. Although meeting these less stringent thresholds suggests that some symptomatic improvement has occurred, it remains likely that residual affective symptoms remain for many patients, which may increase the risk for relapse and worse functional outcomesCitation40,Citation48. In our analyses, 43% of cariprazine 1.5 mg/d patients and 32% of cariprazine 3 mg/d patients achieved ≥50% improvement from baseline in FAST total score and over half of patients in both treatment groups achieved ≥30% improvement from baseline, suggesting a less rigorous but still meaningful level of response for most patients. Across all remission and recovery analyses, single-digit NNTs, which represent a satisfactory treatment benefit in bipolar disorder, were noted for cariprazineCitation49, further supporting the clinical relevance of these findings.

Cariprazine has pharmacologic characteristics that include D3 and D2 receptor partial agonism and preference for the D3 receptor, 5-HT1A partial agonism, and 5-HT2B and 5-HT2A receptor antagonismCitation50. For cariprazine, this receptor binding profile may result in potential benefits on the neural pathways involved in both depressive and cognitive symptoms, which could in turn help to lessen functional impairment. It is interesting to note that greater treatment effect was observed for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d compared with 3 mg/d in these analyses, which suggests an apparent dose response for cariprazine in patients with functional symptoms. This observation is consistent with select findings from the primary study on which these analyses were basedCitation30. While significant reductions in depressive symptoms were seen in both dose groups, the treatment effect versus placebo in MADRS total score reduction (depressive symptoms) was greater in the 1.5 mg/d group (LSMD=-4) compared with the 3 mg/d group (LSMD=-2.5). It is unclear whether this slighter better efficacy in the 1.5 mg dose group was due to better tolerability and higher completion rates in this group versus the 3 mg/d group, or if the difference in treatment effect may alternatively be associated with differences in dopamine receptor occupancy for cariprazine at different dose levels. Namely, it has been shown that cariprazine at lower doses has a greater preference for occupying dopamine D3 receptors than dopamine D2 receptorsCitation51. Since similarly preferential findings for cariprazine 1.5 mg have also been observed in other bipolar depression analyses (e.g. symptom domains, tolerability) it is possible that dose response may be related to the unique pharmacology of cariprazine and higher levels of D3 occupancy at lower doses. Furthermore, since tolerability is an important aspect of a medication’s overall characterization, it is important to mention that a post hoc analysis of the clinical trials in bipolar depression has shown that cariprazine was generally safe and well tolerated in patients with bipolar depression, with high rates of study completion and low rates of discontinuation due to adverse eventsCitation52. Adverse events occurred in more cariprazine-treated patients (60%) than placebo-treated patients (55%), with nausea (8%) and akathisia (7%) occurring in ≥5% of cariprazine patients and twice the rate of placebo. Potential dose-response relationships were observed, with slightly lower rates observed for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d versus 3 mg/d for each event.

Limitations of these analyses include their post hoc nature and the lack of adjustment for multiple comparisons. Since the FAST was only administered at baseline and at week 8, no analysis of function over time was possible so we could not determine the point in treatment when change occurred. Further, since functioning is a complex concept, a rating scale assessment may not capture all aspects of functional change, and a domain-specific instrument (e.g. neuropsychological battery for cognition) might be more informative; moreover, functional remission and recovery may lag behind symptom improvement, and an 8-week study may not be sufficient to fully evaluate changes in function. Additionally, patients were required to meet strict inclusion and exclusion criteria to participate in the study, which may limit the ability to generalize these results to a more diverse bipolar disorder patient population (i.e. manic/mixed episodes, bipolar II) or to patients with other serious mental illnesses. Of note, patients with bipolar II disorder were not included in the primary study. Although cariprazine is also approved to treat schizophrenia and manic/mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder, further research is needed to determine if these preliminary results in bipolar depression are generalizable to other indications. Finally, the 8-week duration of the study suggests that a long-term study evaluating functioning in patients treated with cariprazine is warranted.

Conclusion

In this post hoc analysis of a single 8-week randomized, double-blind study in patients with bipolar depression, treatment with cariprazine was associated with statistically significant improvements over placebo across almost every FAST outcome evaluated, with more consistent results noted for the 1.5 mg/d dose than for the 3 mg/d dose. Consistently significant differences versus placebo in change from baseline suggest that cariprazine may reduce functional impairment (FAST total score), as well as the component individual behavioral domains (FAST subscales). Consistent with the observed LS mean changes from baseline, a significantly greater percentage of cariprazine-treated patients versus placebo-treated patients attained the thresholds that defined functional remission and recovery, with relatively low NNTs, suggesting that treatment with cariprazine may have produced functional changes that were clinically meaningful as well statistically significant. Since cariprazine is one of only 4 medications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat bipolar depression, these preliminary FAST outcomes suggest that cariprazine may be a beneficial treatment option to address the symptoms of bipolar depression and the associated functional impairment that often impedes recovery. While these results are promising, they were based on post hoc findings from a single clinical study; as such, they are not sufficient to make any firm conclusions about efficacy and should be interpreted with caution.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This manuscript was supported by funding from AbbVie. The authors had full control of the content and approved the final version

Declaration of financial/other relationships

EV has received grants from AB-Biotics, Abbott, Allergan (now AbbVie), Angelini, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, and Takeda; has served as consultant/advisor for AB-Biotics, Abbott, Allergan (now AbbVie), Angelini, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, and Takeda; and has served as a CME speaker unrelated to the present work for the following entities: AB-Biotics, Abbott, Allergan (now AbbVie), Angelini, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, and Takeda. JRC has received federal funding from the Department of Defense, Health Resources Services Administration and National Institute of Mental Health; research support from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Cleveland Foundation, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, NARSAD, Repligen, Stanley Medical Research Institute, Takeda, and Wyeth; has served on advisory boards of Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Dainippon Sumitomo, EPI Q, Inc., Allergan (now AbbVie), France Foundation, Gedeon Richter Plc., GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Merck, Neurosearch, OrthoMcNeil, Otsuka, Pfizer, Repligen, Schering-Plough, Servier, Solvay, Supernus, Synosia, Takeda, and Wyeth; and has provided CME lectures supported by AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, France Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Sanofi Aventis, Schering-Plough, Pfizer, Solvay, and Wyeth. MT has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Abbott, BMS, Lilly, GSK, J&J, Otsuka, Roche, Lundbeck, Elan, Allergan (now AbbVie), Alkermes, Merck, Minerva, Neuroscience, Pamlab, Alexza, Teva, Sunovion, Gedeon Richter, and Wyeth and was an employee at Lilly (1997 to 2008). His spouse is a former employee at Lilly (1998-2013). JW has been a consultant or key opinion leader for Sunovion, Allergan (now AbbVie), Neuocrine, Teva, Neuroflow, Jansen, and the ANCC. She has also served on the boards Nurse’s Against Violence Unite, the St. Louis Nurse’s in Advanced Practice, the Missouri Nurse’s Association. She has done CME presentations for the St. Louis Nurses in Advanced Practice, the Missouri Nurses Association, the Missouri Nurses in Advanced Practice and the Sinclair School of Nursing Annual Nursing Conference. She has also appeared in national ad campaigns for AbbVie and assisted with implementation of new online marketing promotion for AbbVie and Genomind; and has served as a speaker for Ostuska/Lundbeck, Neurocrine, Avanir, Genomind, Neurocrine, Cambridge Brain Sciences, Klara Telehealth, Athena Health, and Allergan (now AbbVie). WRE is an employee of AbbVie and is a shareholder of AbbVie, AstraZeneca, and Eli Lilly.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from CMRO for their review work. One of these reviewers has disclosed that they have received manuscript or speaker’s fees from Astellas, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Elsevier Japan, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Yakuhin, Lundbeck, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Shire, Tsumura, Wiley Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and research grants from Eisai, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma and Shionogi. The remaining reviewers have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Statistical analyses were conducted by Qing Dong of TechDataService Company LLC, a contractor of AbbVie. Writing and editorial assistance were provided by Carol Brown, MS, ELS, of Prescott Medical Communications Group (Chicago, IL, USA), a contractor of AbbVie. We wish to thank Mehul D. Patel (at AbbVie at the time of the study) for his contributions to this manuscript.

References

- Miller S, Dell'Osso B, Ketter TA. The prevalence and burden of bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2014;169 (Suppl 1):S3–S11.

- MacQueen GM, Young LT, Joffe RT. A review of psychosocial outcome in patients with bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103(3):163–170.

- Tohen M, Hennen J, Zarate CM, Jr, et al. Two-year syndromal and functional recovery in 219 cases of first-episode major affective disorder with psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(2):220–228.

- Tohen M, Waternaux CM, Tsuang MT. Outcome in mania. A 4-year prospective follow-up of 75 patients utilizing survival analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(12):1106–1111.

- Tohen M, Waternaux CM, Tsuang MT, et al. Four-year follow-up of twenty-four first-episode manic patients. J Affect Disord. 1990;19(2):79–86.

- Zarate CA, Jr., Tohen M, Land M, et al. Cognition in bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Q. 2000;71(4):309–329.

- Rosa AR, Sanchez-Moreno J, Martinez-Aran A, et al. Validity and reliability of the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) in bipolar disorder. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2007;3(1):5.

- Rosa AR, Reinares M, Franco C, et al. Clinical predictors of functional outcome of bipolar patients in remission. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(4):401–409.

- Bonnin CM, Martinez-Aran A, Torrent C, et al. Clinical and neurocognitive predictors of functional outcome in bipolar euthymic patients: a long-term, follow-up study. J Affect Disord. 2010;121(1–2):156–160.

- Calabrese JR, Hirschfeld RM, Frye MA, et al. Impact of depressive symptoms compared with manic symptoms in bipolar disorder: results of a U.S. community-based sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(11):1499–1504.

- Gitlin MJ, Mintz J, Sokolski K, et al. Subsyndromal depressive symptoms after symptomatic recovery from mania are associated with delayed functional recovery. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(05):692–697.

- Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):543–552.

- McIntyre RS. Understanding needs, interactions, treatment, and expectations among individuals affected by bipolar disorder or schizophrenia: the UNITE global survey. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(Suppl 3):5–11.

- Sanchez-Moreno J, Martinez-Aran A, Tabares-Seisdedos R, et al. Functioning and disability in bipolar disorder: an extensive review. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(5):285–297.

- Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC, et al. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9783):2093–2102.

- Kapczinski NS, Narvaez JC, Magalhaes PV, et al. Cognition and functioning in bipolar depression. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2016;38(3):201–206.

- Rosa AR, Reinares M, Michalak EE, et al. Functional impairment and disability across mood states in bipolar disorder. Value Health. 2010;13(8):984–988.

- Samalin L, Boyer L, Murru A, et al. Residual depressive symptoms, sleep disturbance and perceived cognitive impairment as determinants of functioning in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:280–286.

- Simon GE, Bauer MS, Ludman EJ, et al. Mood symptoms, functional impairment, and disability in people with bipolar disorder: specific effects of mania and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(08):1237–1245.

- Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Unutzer J, et al. Severity of mood symptoms and work productivity in people treated for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(6):718–725.

- Goldberg JF, Harrow M. Subjective life satisfaction and objective functional outcome in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders: a longitudinal analysis. J Affect Disord. 2005;89(1–3):79–89.

- Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Solomon DA, et al. Psychosocial disability and work role function compared across the long-term course of bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2008;108(1–2):49–58.

- Shippee ND, Shah ND, Williams MD, et al. Differences in demographic composition and in work, social, and functional limitations among the populations with unipolar depression and bipolar disorder: results from a nationally representative sample. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:90.

- van der Voort TY, Seldenrijk A, van Meijel B, et al. Functional versus syndromal recovery in patients with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):e809-14.

- Martinez-Aran A, Vieta E, Colom F, et al. Cognitive impairment in euthymic bipolar patients: implications for clinical and functional outcome. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(3):224–232.

- Martinez-Aran A, Vieta E, Torrent C, et al. Functional outcome in bipolar disorder: the role of clinical and cognitive factors. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(1–2):103–113.

- Serafini G, Canepa G, Adavastro G, et al. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:149.

- Wingo AP, Baldessarini RJ, Holtzheimer PE, et al. Factors associated with functional recovery in bipolar disorder patients. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(3):319–326.

- Chen M, Fitzgerald HM, Madera JJ, et al. Functional outcome assessment in bipolar disorder: a systematic literature review. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(3):194–214.

- Durgam S, Earley W, Lipschitz A, et al. An 8-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of the safety and efficacy of cariprazine in patients with bipolar I depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(3):271–281.

- Earley W, Burgess MV, Rekeda L, et al. Cariprazine treatment of bipolar depression: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):439–448.

- Earley WR, Burgess MV, Khan B, et al. Efficacy and safety of cariprazine in bipolar I depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Bipolar Disord. 2020;22(4):372–384.

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389.

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62.

- Guy W. The Clinical Global Impression Severity and Improvement Scales. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Rockville (MD): National Institute of Mental Health, US Department of Health, Education and Welfare publication (ADM); 1976. p. 218–222.

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, et al. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435.

- Althouse AD. Adjust for multiple comparisons? It's not that simple. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(5):1644–1645.

- Bonnin CM, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares M, et al. Thresholds for severity, remission and recovery using the functioning assessment short test (FAST) in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2018;240:57–62.

- Beyer JL. An evidence-based medicine strategy for achieving remission in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(Suppl 3):31–37.

- Muller MJ, Szegedi A, Wetzel H, et al. Moderate and severe depression. Gradations for the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale. J Affect Disord. 2000;60(2):137–140.

- Sanchez-Moreno J, Martinez-Aran A, Vieta E. Treatment of functional impairment in patients with bipolar disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(1):3.

- Sole B, Bonnin CM, Jimenez E, et al. Heterogeneity of functional outcomes in patients with bipolar disorder: a cluster-analytic approach. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;137(6):516–527.

- Jaeger J, Berns S, Loftus S, et al. Neurocognitive test performance predicts functional recovery from acute exacerbation leading to hospitalization in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(1–2):93–102.

- Tohen M, Frank E, Bowden CL, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) Task Force report on the nomenclature of course and outcome in bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(5):453–473.

- Harvey PD. Defining and achieving recovery from bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 9):14–18.

- Vieta E, Torrent C. Functional remediation: the pathway from remission to recovery in bipolar disorder. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(3):288–289.

- Berk M, Ng F, Wang WV, et al. The empirical redefinition of the psychometric criteria for remission in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;106(1–2):153–158.

- Ketter TA, Miller S, Dell'Osso B, et al. Balancing benefits and harms of treatments for acute bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2014;169(Suppl 1):S24–S33.

- Citrome L. Cariprazine for the treatment of schizophrenia: A review of this dopamine d3-preferring d3/d2 receptor partial agonist. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2016;10(2):109–119.

- Girgis RR, Slifstein M, D'Souza D, et al. Preferential binding to dopamine D3 over D2 receptors by cariprazine in patients with schizophrenia using PET with the D3/D2 receptor ligand [(11)C]–(+)–PHNO. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233(19–20):3503–3512.

- Earley WR, Burgess M, Rekeda L, et al. A pooled post hoc analysis evaluating the safety and tolerability of cariprazine in bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2020;263:386–395.