Abstract

Background

Aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency is a rare neurological condition, with an estimated global prevalence of 1:32,000 to 1:90,000 live births. AADC deficiency is associated with a range of symptoms and functional impairments, but these have not previously been explored qualitatively. This study aimed to understand the symptoms of AADC deficiency and its impact on individuals’ health-related quality of life.

Methods

Qualitative interviews were conducted with caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency in Italy, Spain, Portugal and the United States. An interview guide was developed with input from clinical experts and caregivers, and explored the symptoms and impacts of AADC deficiency. Interviews were conducted by telephone and were recorded and transcribed. Data were analysed using thematic analysis and saturation was recorded.

Results

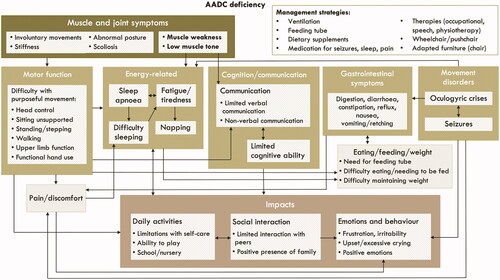

Fourteen caregivers took part, who provided care to 13 individuals with AADC deficiency aged 1–15 years. All individuals had impaired motor function, which was attributed to low muscle tone and muscle weakness. The level of motor function varied considerably, ranging from no motor function (no head control) to being able to take a few steps without support. Other impairments included cognitive impairment, communication difficulties, movement disorders (e.g. oculogyric crises), gastrointestinal symptoms, eating difficulties, fatigue and sleep disruption. Most individuals were completely dependent on their caregivers for all aspects of their lives. This limited function had a negative impact on their ability to socialise with their peers and on their emotional wellbeing. These concepts and relationships are illustrated in a conceptual model, and moderating factors (e.g. physiotherapy and medication) are discussed.

Conclusion

This is the first qualitative study to report on the experience of living with AADC deficiency. Caregivers report individuals with AADC deficiency experience a wide range of symptoms and functional impairments, which have a substantial impact on their health-related quality of life.

Introduction

Aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency (MIM number #608643) is a rare, autosomal recessive neurometabolic disorder that leads to a severe deficiency of serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine and epinephrine [Citation1]. The prevalence of AADC deficiency varies globally, but has been estimated at between 1:64,000 and 1:90,000 births in the USA, 1:116,000 in the European Union, 1:162,000 in Japan and 1:32,000 in Taiwan [Citation2–4]. AADC deficiency is associated with severe developmental delay, resulting in a range of symptoms and functional impairments [Citation1,Citation5]. Symptoms typically present during the first year of life [Citation6], but due to the rarity of the disease, diagnosis requires genetic testing and at least two of three key diagnostic tests to be positive [Citation1].

There are no FDA approved treatments specifically for AADC deficiency, however, the current recommended treatment currently includes dopamine agonists, monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors, and vitamin B6 [Citation1,Citation7]. This is typically supplemented with symptomatic treatment of movement disorders or sleep disturbance [Citation1,Citation7]. In addition, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy may help improve symptoms and functional impairments [Citation8]. Clinical trials are currently evaluating the efficacy of gene therapy [Citation9], which aims to deliver a functional copy of the dopa decarboxylase (DDC) gene, the faulty gene in individuals with AADC deficiency [Citation1]. Previous research has shown that gene therapy can improve the motor function of individuals with AADC deficiency [Citation10–12], and may also improve physiological and cognitive functioning.

Although the symptoms of AADC deficiency have been described in the literature [Citation1], limited research has been conducted with patients or caregivers. A survey of physicians and caregivers, with data on 63 individuals with AADC deficiency, found that 70% had profound motor impairment, and other commonly reported symptoms included hypotonia, developmental delay, oculogyric crises (sustained dystonic, conjugate and upward deviation of the eyes lasting from seconds to hours) [Citation13], sleep disturbance, irritable mood, and feeding difficulties [Citation5]. A recent vignette study, which included groups discussions with caregivers (N = 3), identified additional caregiver-reported symptoms, including gastrointestinal, autonomic and respiratory symptoms, and seizures [Citation14].

Qualitative research allows for an in-depth exploration of the impact of a disease from the perspective of the participant, such as a patient or caregiver. In qualitative research, participants are given the opportunity to speak freely about their experiences outside the constraints of closed question surveys or questionnaires. This generates rich data which can highlight symptoms and impacts that were previously unknown. This is particularly important in rare diseases, as it enables a deeper understanding of the burden of disease and provides patients and caregivers with a voice. Qualitative research can also highlight important concepts to measure when evaluating new treatments in patient-centred clinical trials.

No qualitative studies have been conducted with individuals with AADC deficiency or their caregivers. The aim of this study was to explore the caregiver perspective of the symptoms, functional impairments and impacts experienced by individuals with AADC deficiency who are treated with standard of care.

Methods

Design and participants

Qualitative interviews were conducted with caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency in Italy, Portugal, Spain and the United States. The aim of the interviews was to explore the symptoms and impacts of AADC deficiency. The interviews were conducted with informal (unpaid) caregivers, as the individuals with AADC deficiency were too severely impaired to participate in an interview. Participant inclusion criteria were (i) being the main caregiver (providing at least 50% of daily care) of an individual with AADC deficiency, (ii) willing and able to provide informed consent, (iii) aged 18 years or over, (iv) live in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, France, Italy, Spain or Portugal. In addition, in order for caregivers to be eligible, the individuals needed to have a confirmed diagnosis of AADC deficiency based on at least two of the three tests: 1) cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) neurotransmitter analysis, 2) molecular genetic testing of the DDC gene, 3) blood AADC enzyme activity. Caregivers of individuals who had been treated with gene therapy were excluded.

Study materials

A semi-structured interview guide was developed based on the published literature on the health-related quality of life of individuals with AADC deficiency, consultation with clinical experts and informal interview discussions with caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency in Spain (N = 2). The interview guide comprised mainly of open-ended questions on the individual with AADC deficiency’s diagnosis and symptoms, as well as the impacts on their daily life and health-related quality of life, and the impacts on their caregiver (caregiver results are reported elsewhere).

A background questionnaire was developed to collect information on socio-demographics and the individual with AADC deficiency’s disease background and treatment.

Ethics review and approval

This study was submitted for ethical review by the WIRB-Copernicus Group Independent Review Board and was granted an exemption (tracking number: #1-1327023-1).

Recruitment and interviews

Participants were recruited by a specialist recruitment agency using a variety of sources including social media, patient support groups and clinician referrals. Participants were sent an information sheet about the study along with a background questionnaire to complete and return by email. The interviews in the United States were conducted in English by two study authors (KW and HS), both with PhDs in psychology and more than 15 years combined qualitative research experience. The remaining interviews were conducted by trained interviewers in each study country in the local language. None of the participants were known to the interviewers. All interviews were conducted by telephone/videoconference between September and December 2020. Verbal informed consent was taken at the start of the interview, then the interviews followed the semi-structured interview guide and lasted around an hour. Interviews were recorded and transcribed, then translated into English for analysis by a specialist translation vendor.

Analyses

Data from the background questionnaire were summarised using descriptive statistics. Data from the interviews were analysed using thematic analysis in MAXQDA. Two researchers (KW and HS) read all the transcripts and developed a coding framework based on the topics covered in the interview guide. One researcher (HS) then coded a sample of transcripts, and these were reviewed by a second researcher (KW) and discrepancies were discussed. The coding framework was revised following this discussion, and the remaining transcripts were coded. Additional data-driven amendments were made to the coding framework throughout the coding process.

The codes were then grouped into themes to describe the experience of living with AADC deficiency. A conceptual model was developed to illustrate the relationship between these themes. The symptoms and impacts were described in boxes, and arrows were used to indicate the direction of the relationships between these symptoms and impacts. These relationships were based solely on the qualitative data.

Best practice in qualitative research is to keep conducting interviews until data saturation is reached. Data saturation has been defined as the point at which no new insights are obtained, or no new themes are identified in the data [Citation15]. Saturation matrices were used to monitor the frequency of reported concepts across the interviews, where the concepts were listed in rows and the columns were the interviews in order of completion [Citation16].

Results

Sample characteristics

Fourteen interviews were conducted with caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency, including 10 mothers, two fathers, one brother and one aunt. Two caregivers were parents of the same individual. The caregiver characteristics are shown in and the characteristics of the individuals with AADC deficiency are shown in . The saturation matrices indicated that saturation had been reached, with 94% (16/17) concepts being spontaneously reported in the first 50% of interviews and no new concepts spontaneously reported in the final interview ().

Table 1. Caregiver characteristics (N = 14)a.

Table 2. Characteristics of individuals with AADC deficiency (N = 13).

Table 3. Data saturation matrix for symptoms, function and impacts.

Overview symptoms, function and impacts of AADC deficiency

In summary, muscle and joint symptoms, particularly muscle weakness and low muscle tone, had a direct impact on motor function, energy-related symptoms and communication. Other symptoms and functional impairments included impaired cognitive function, gastrointestinal symptoms, issues with eating/feeding and weight, movement disorders and pain. These symptoms and functional impairments were related to each other and also had a wider impact on the individual’s daily activities, social interaction, and emotions and behaviour. These symptoms, functional impairments and impacts are described in further detail in the sections below and illustrated in a conceptual model ().

Figure 1. Conceptual model illustrating the relationships between symptoms and impacts of AADC deficiency. The conceptual model is designed to be read from the top, where there are the most proximal symptoms and functional impairments, to the bottom, where there are more distal impacts. The arrows show the relationships between the concepts, which are either unidirectional or bidirectional (for example, gastrointestinal symptoms impact eating and vice versa). Some relationships are between the larger external boxes, for example, all muscle and joint symptoms were reported to impact motor function. Other relationships are between the internal boxes, for example, muscle weakness and low muscle tone were reported to impact communication, but not cognitive function.

Symptoms and function

Muscle and joint symptoms

Nearly all caregivers stated that the individual they care for had severe muscle weakness across their entire body. They described how this muscle weakness limited their motor function, including their ability to hold their head up, sit unsupported, stand, walk and use their upper limbs. Others reported that this muscle weakness made the individual tired or fatigued, or affected their ability to talk. Muscle weakness was sometimes attributed to the individual having low or no muscle tone. Some described them as being like a “rag doll” or “floppy” and explained how this made it very difficult for them to control their muscles and prevented them from making purposeful movements. As well as struggling to make purposeful movements, some caregivers described how the individuals made involuntary movements, such as muscle twitches or spasms. A few caregivers also mentioned that the individual sometimes experienced muscle or joint stiffness, or had a rigid or abnormal posture, which was sometimes attributed to scoliosis.

Motor function

All caregivers reported that the individual they cared for had impaired motor function. This was generally attributed to muscle weakness and low muscle tone, which prevented the individual from making purposeful movements.

He has no muscle tone and this doesn’t help him, he cannot control his head, his arms, his legs, he cannot control his motion - 10 years (203)

The level of motor function varied, with some participants reporting that the individual was unable to hold their head, and others reporting that they were able to walk.

Around half of the caregivers reported that the individual with AADC deficiency was able to control their head and hold it level, although most explained that this ability depended on their energy level or muscle strength at the time. The remaining caregivers said the individuals they cared for were unable to hold their head. Fewer than half of caregivers reported that the individual was able to sit unsupported, although again this depended on their energy levels. Even if they were able to, most caregivers said they do not leave them to sit unsupported for any period of time due to concerns about their safety and ability to maintain their muscle strength. The remaining caregivers described how the individuals they cared for were unable to sit unsupported.

She can't sit…if I would just sit her on the ground, she would, like, fall to the side. I have to have the boppy pillow or I have to have her in her bamboo chair at all times. Something around her, positioning her up - 1 year (604)

The majority of caregivers reported that the individual with AADC deficiency was able to stand when fully supported. This included some participants who also said that the individual did not have head control. As with head control and sitting, the individual’s ability to stand was reported to vary depending on their energy levels, muscle strength and mood. One caregiver reported that the individual they cared for was able to stand with minimal support when they were younger, but had regressed and were no longer able to do this. Less than a third of caregivers reported that the individual had some ability to walk short distances with minimal or no support.

He probably could take a good, 10 footsteps, maybe with no support, going very slow…I'm more, holding him with a hand to give some strength, but I'm not supporting him to walk. I guess it's more something to lean on, kind of something in the event, it's a comfort measure - 601 (6 years)

Most described how they would walk at a slow pace and would need to take rests. The furthest reported distance that an individual was able to walk was around 20 feet or around 10 steps with support. Again, this was reported to vary according to the individual’s energy levels.

Muscle weakness and low muscle tone also had an impact on upper limb function. Most caregivers reported that the individual with AADC deficiency was unable to raise their arms above their head, which limited their ability to reach for objects.

If I put a toy within her reach to see if she grasps it, she is not able to do that - 15 years (301)

Some also described how the individual had limited functional hand use, which meant they had difficulty grasping, holding and manipulating objects, such as toys. Others explained that the individual was able to handle large objects which were easier to hold onto and grab, for example, larger crayons. Some of these individuals were also reported to be able to pick up finger foods or hold a spoon.

Fatigue and tiredness

The majority of caregivers reported that the individual with AADC deficiency experienced fatigue and tiredness. This was generally reported to occur at the end of a long day, but for some it was described as constant. The fatigue was attributed to muscle weakness, which made even the simplest movement or activity a huge effort for the individual.

Imagine you have just run a marathon and you're exhausted and tired, so, you take a few steps, and you want to lean for support. That's kind of imagining living a life like this. The fatigue is always extreme and it's doing everything in very small doses…everything is in small increments, a lot of rest is needed, fatigue is huge - 6 years (601)

Sleep disturbance

Several caregivers reported that the individual they cared for had sleep apnoea and around half required ventilation at night in order to support their breathing and maintain their oxygen levels. One of these individuals also required ventilation during the day. Some reported that the ventilation helped them sleep and made them less tired the following day. Even with ventilation, most caregivers described how the individual with AADC deficiency had difficulty getting to sleep. The reasons for this were not always clear, but some caregivers thought it may be due to pain or discomfort, or because they sometimes had seizures at night. Several caregivers reported that they gave the individual melatonin to help them sleep. Some caregivers described how the individual they cared for often napped during the day, and this was attributed to their fatigue and tiredness.

Communication and cognitive function

Most caregivers described the individual’s cognitive function as extremely limited. For example, one caregiver of a 10 year old described how the individual was like a baby and had a schooling level of zero. Although their cognitive function was limited, several were described as being able to recognise objects, sounds and people. This recognition was usually determined by the caregiver noticing non-verbal cues, for example, some described how the individual would smile in recognition when they saw their teddy bear or a particular character on television. Similarly, others described how the individual would respond to familiar voices, such as their parent or sibling. Most caregivers said the individual’s cognitive function would vary depending on whether they were having a good day or a bad day.

Some caregivers described how they thought the individual’s difficulties were due to limitations with communication rather than a lack of cognitive ability.

It's not necessarily that they're mentally incapable or that they don't understand, because they do understand. I think I honestly believe that he does understand. It's more that he can't, it, it's stuck there, and it can't come out. So, he, I believe I see in his eyes that he recognizes and knows things more than he can use and communicate to me… I believe the memory is there…other than misfiring the signals and maybe not having the capacity to control the muscles. I feel that his memory and recognition is, is there. I believe that - 4 years (602)

None of the individuals were able to communicate verbally using full sentences, but some caregivers reported that they were able to say short phrases or words in order to respond to questions or express themselves. However, most caregivers reported that the individual they cared for could not speak, but would make sounds, or use eye movements, facial expression or body gestures (e.g. tapping) to communicate. Several caregivers reported that the individual’s ability to communicate varied from day to day. One caregiver attributed the individual’s lack of verbal communication to their muscle weakness.

She is not able to talk because she has muscle weakness but she communicates with us with her eyes - 15 years (301)

Gastrointestinal symptoms

Most caregivers reported that the individual with AADC deficiency experienced gastrointestinal symptoms, including problems with digesting food, diarrhoea, constipation, reflux, nausea and vomiting. The most commonly reported symptom was diarrhoea, which was generally attributed to the type of food (e.g. sugary fruits) or the consistency of food (e.g. pureed). Several caregivers mentioned that they tried to manage the individual’s gastrointestinal symptoms by providing foods high in fibre and protein or by using a feeding tube to manage their food intake.

He has trouble with digestion, that’s why the doctor also put him on the feeding tube… it seemed like he was getting tummy troubles, like his stomach would hurt after eating – 2 years (605)

Eating, feeding and weight

Five caregivers reported that the individuals they cared for ate through a feeding tube. Some individuals ate all of their food this way because they were unable to eat by mouth or were at risk of choking due to a lack of head control. Other caregivers described how the individual did not have a good appetite and lacked interest in food, so they had a feeding tube to ensure they got enough nutrients and to help them maintain their weight. Others had a feeding tube to help manage their gastrointestinal symptoms, with one caregiver saying that the individual no longer experienced gastrointestinal symptoms after the feeding tube had been inserted. Some individuals who had a feeding tube also ate some food by mouth. These caregivers explained that this was mainly for the individual’s enjoyment because they got pleasure from eating. The remaining caregivers said that the individuals ate all of their food by mouth, but some had to be spoon fed as they were unable to feed themselves. These caregivers described how they gave the individuals baby food, or blended their meals to make it easier for them to eat. Other caregivers described how the individual was able to eat “finger foods”, but needed help with utensils.

Oculogyric crises

The majority of caregivers reported that the individual experienced episodes of oculogyric crises or described symptoms of such episodes. These episodes were reported to affect the whole body and included characteristics such as eyes rolling back in the head, staring upwards, stiffness, shivering, pain, and involuntary movements.

The first thing I notice is her stare. Her eyes seem empty, she seems to be in another world. Her eyes roll upward a lot. For instance, the iris comes forward and she “buries” it, I do not know how to explain it. And she chews her tongue a lot. She starts moving, the arms also start to tremble and she shivers. It is hard to control, it is difficult - 15 years (301)

Some caregivers also described after effects of episodes of oculogyric crises, including fatigue, nausea and changes in mood. The frequency of these episodes varied between individuals, with some caregivers reporting that they occurred multiple times per week and others every few months. Similarly, the length of the episodes varied from a few minutes to several hours. None of the caregivers reported any triggers of oculogyric crises, and they were considered to be a part of the AADC deficiency pathophysiology. It was noted that the term oculogyric crisis was not well understood by all caregivers and was often used interchangeably with seizures.

Seizures

Most caregivers reported that the individual had experienced seizures at some point in their lives. Similar to oculogyric crises, these seizures were described as affecting the whole body and included symptoms such as shivering, involuntary movements and fatigue. Seizures were reported to occur both during the day and at night, and there were no reported triggers. Several caregivers reported that the individual’s seizures were controlled by medication.

Pain and discomfort

Most caregivers said that they thought the individual they care for experienced pain and discomfort. Although most individuals were unable to communicate their pain verbally, caregivers considered excessive crying as an indicator of pain or discomfort. Muscle and joint pain were most commonly reported, and these were attributed to the individual sitting or lying in the same position for long periods of time due to their inability to move. As a result, caregivers reported that they needed to keep changing the individual’s position to keep them comfortable. Other caregivers said that the individual appeared to be in pain and discomfort during episodes of oculogyric crises. A few caregivers said that the individual experienced stomach pain or discomfort after eating or as a result of constipation or diarrhoea.

Impacts on daily life and health-related quality of life

All caregivers talked about the severely limiting nature of AADC deficiency and how the individual was unable to do any of the usual activities of other children their age.

He doesn’t have a normal daily life…I can’t even imagine what things feel like being him. That’s the truth…there are no happy baby moments during the day. The best I hope for is no issues - 1 year (607)

Daily activities

The individual’s level of motor function had an impact on their ability to carry out their daily activities. Some individuals had no motor function and were therefore completely dependent on their caregivers for all aspects of their self-care, including washing, dressing and moving around. Those with some motor function were able to perform some of these tasks with assistance, including bathing, cleaning their teeth and choosing which clothes to wear.

Most caregivers described how the individuals were extremely limited in their leisure activities, particularly those with very limited motor function.

A typical day, that is not normal, is more or less this. From the bed to the pushchair, watching cartoons. She does nothing else - 15 years (301)

Caregivers also described how they would take the individual for walks in the park in a wheelchair so they could be around other children. Some individuals were able to play with toys to a limited extent, but would usually need the help of their caregiver because of their physical limitations.

I help him build a tower for example, I guide his arm, I make him hold the construction, we get the orange piece and we put it on the blue piece. I guide him so that he can complete the action, but he wouldn’t be able to do it alone. - 204 (8 years)

Those who were less physically limited were also less restricted in their daily activities, with some being able to play in the park, play with animals, do colouring and go swimming. However, these individuals still required a lot of assistance and constant monitoring by their caregivers and were not able to do these things independently.

Around half of the caregivers reported that the individuals attended school or nursery. This included both specialists schools and mainstream schools with specialist support. They described how the individuals mainly worked with their teachers on some limited activities, rather than doing the same activities as other children. Several caregivers said that the main reason for the individual attending school was for their enjoyment and to be around other children. Some children only attended school or nursery part-time and others did not attend at all.

Social interaction

More than half of caregivers said that the individual was unable to play or interact with other children because of their impaired motor and cognitive function.

He can’t play with other children, because he can’t really walk, he can’t, hold his head up, so no… he can’t like actively participate with other toddlers his age - 2 years (605)

Others described how the individual had some interaction, but they were restricted to certain activities because of their limitations. Most described how the individual would need to be supervised while playing with other children, and some said they were concerned that other children would not understand what they were going through. This had led some caregivers to limit the individual’s social interaction to family members.

Emotions and behaviour

Several caregivers described the emotional impact of AADC deficiency on the individual. The most commonly reported emotion was frustration, with caregivers describing how the individual would become frustrated when they wanted something but were unable to do it themselves or communicate their needs to others.

It can be really frustrating with the inability to verbalise or the inability to engage in something physical - 4 years (606)

Several caregivers said they would know the individual was frustrated because they would cry excessively or be irritable in certain situations. Some reported that this was particularly common when they were tired and would often improve after a nap or a night’s sleep.

Some caregivers reported that they thought the individual was sometimes sad because they would cry excessively. However, most acknowledged that it was difficult to tell because it was common for individuals of their age to cry and they were unable to communicate their feelings. In contrast, several caregivers described the individuals as happy, relaxed and calm and reported that they would smile a lot. This was attributed to them not knowing any other life or knowing what they were missing out on.

Management of AADC deficiency

Caregivers described a range of management strategies that they used to help the individuals manage their AADC deficiency. As described above, some individuals received support from a ventilator or feeding tube to help manage their symptoms. Several caregivers mentioned that they used a pushchair or a wheelchair to help the individual get around. Some caregivers reported that the individual took medications to manage sleep, pain and seizures, and others received therapies to help improve their symptoms or functional impairments. Most individuals worked with a physiotherapist to help build up their muscle strength, and some caregivers had noticed this improved their motor function. Others had occupational therapy to help with their hand function or speech therapy to help with their verbal communication skills.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study conducted with the caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency. The results provide insights into the symptoms, impacts and challenges experienced by individuals with AADC deficiency from the perspective of caregivers. Caregivers reported that muscle weakness and low muscle tone were core symptoms of AADC deficiency and that these were associated with limitations in motor function, fatigue and communication. Other important symptoms and functional impairments included limitations with communication, impaired cognitive function, gastrointestinal symptoms, eating and feeding challenges, movement disorders, and pain. These symptoms and functional impairments were reported to have a wide-ranging impact on the lives of individuals with AADC deficiency, including on daily activities, social interaction and emotional wellbeing. Overall, the findings highlight a substantial burden of living with AADC deficiency and significant unmet need.

Although some of the symptoms and functional impairments have previously been reported in the literature [Citation5,Citation14], this is the first study to provide qualitative data on the experience of AADC deficiency from the perspective of caregivers. Our findings highlight the wide-ranging experience of individuals; for example, some had no motor function, required ventilation and were fed through a feeding tube, and others were able to walk and feed themselves. This is also the first qualitative with caregivers study to describe the broader life experience of individuals with AADC deficiency, highlighting the experiences they are able to have and those which they miss out on.

The patient-centred conceptual model extends these findings by showing how the reported symptoms, functional impairments and impacts relate to each other. Given the many relationships between the concepts, this highlights how a potential improvement or worsening in one area can have a knock-on effect on other symptoms and areas of life. The conceptual model also provides a useful tool for informing the development of patient-centred measurement strategies for clinical trials of new treatments. This includes both identifying concepts that may be important to measure, validating existing caregiver-reported questionnaires [Citation17], and informing the development of new questionnaires.

Although this study provides novel insights, it also has some limitations. Recruitment was conducted through a specialist recruitment agency and diagnosis of AADC deficiency was self-reported. In addition, participants were screened using pre-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria, but this method is not as robust as clinician-confirmed diagnosis. Participants were sought from countries across Europe and North America, but the majority of participants were recruited from the United States and Italy. However, as AADC deficiency is an extremely rare disease, recruitment relies on a limited pool of individuals agreeing to take part. The data saturation matrix indicated that saturation had been reached, but given the heterogeneity in the reported symptom experience, it is possible that additional interviews may have identified new concepts. Although qualitative research is not designed to be representative, the sample were predominantly White and university educated, so the findings may vary in other populations. While this paper provides a comprehensive overview of the symptoms and impacts experienced by individuals with AADC deficiency, it is also important to explore the impact on caregivers. The findings on the impact of caring for an individual with AADC deficiency will be presented separately. Future research could also explore the experience of individuals with AADC deficiency by disease severity or other sub-groups.

Conclusions

Individuals with AADC deficiency experience a range of symptoms and functional impairments, which have a substantial impact on their daily life and health-related quality of life. As a result, they require round the clock care or support from a caregiver to perform their daily activities. Treatments which improve function and symptoms have the potential to improve the daily lives and health-related quality of life of these individuals.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by PTC Therapeutics International Ltd.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

KW, HS and SA are employees of Acaster Lloyd Consulting Ltd. CW, SO’N and KB are employees of PTC Therapeutics. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design of the study. The study materials were developed by KW, HS and SA and all authors provided feedback. The English language interviews were conducted by KW and HS. The analysis was conducted by KW and HS and the conceptual model was developed by KW, HS and SA. KW and HS drafted the manuscript and all authors provided feedback. All authors approved the final submitted version.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the caregivers who took part in the study.

References

- Wassenberg T, Molero-Luis M, Jeltsch K, et al. Consensus guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency. Orphanet J Rare Dis. (1)2017;12:12.

- Whitehead N, Schu M, Erickson SW, et al. Estimated prevalence of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency in the United States, European Union, and Japan. Proceedings of the Poster session resented at: Annual Congress of the European Society Gene and Cell Therapy; 2018 Oct 16–19; Lausanne.

- Hyland K, Reott M. Prevalence of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency in at-risk populations. Pediatr Neurol. 2020;106:38–42.

- Chien YH, Chen PW, Lee NC, et al. 3-O-methyldopa levels in newborns: result of newborn screening for aromatic L-amino-acid decarboxylase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. (4)2016;118:259–263.

- Pearson TS, Gilbert L, Opladen T, et al. AADC deficiency from infancy to adulthood: symptoms and developmental outcome in an international cohort of 63 patients. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2020;43(5):1121–1130.

- Brun L, Ngu LH, Keng WT, et al. Clinical and biochemical features of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Neurology. (1)2010;75:64–71.

- Fusco C, Leuzzi V, Striano P, et al. Aromatic L-amino Acid Decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency: results from an Italian modified Delphi consensus. Ital J Pediatr. 2021;47(1):13.

- Physiotherapy for AADC Deficiency [Internet]. AADC News; 2019 [cited 2021 Mar 1]. Available from: https://aadcnews.com/physiotherapy-for-aadc-deficiency/.

- A single-stage, adaptive, open-label, dose escalation safety and efficacy study of AADC deficiency in pediatric patients (AADC). [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2021 Mar 22]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02852213?cond=AADC+Deficiency&draw=1&rank=1.

- Hwu WL, Muramatsu SI, Tseng SH, et al. Gene therapy for aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(134):134ra61.

- Chien YH, Lee NC, Tseng SH, et al. Efficacy and safety of AAV2 gene therapy in children with aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: an open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2017;1(4):265–273.

- Kojima K, Nakajima T, Taga N, et al. Gene therapy improves motor and mental function of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Brain. 2019;142(2):322–333.

- Barow E, Schneider SA, Bhatia KP, et al. Oculogyric crises: etiology, pathophysiology and therapeutic approaches. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2017;36:3–9.

- Hanbury A, Smith AB, Buesch K. Deriving vignettes for the rare disease AADC deficiency using parent, caregiver and clinician interviews to evaluate the impact on health-related quality of life. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2021;12:1–12.

- Bowen GA. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: a research note. Qual Res. 2008;8(1):137–152.

- Kerr C, Nixon A, Wild D. Assessing and demonstrating data saturation in qualitative inquiry supporting patient-reported outcomes research. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(3):269–281.

- AADCd Symptom Questionnaire. [Internet]. AADC Research Trust. [cited 2021 Mar 2]. Available from: https://www.aadcresearch.org/aadcd-symptom-questionnaire.