Abstract

Introduction

A multidisciplinary panel of physicians was convened to gain understanding of the relationship between thromboembolic events (TEs) and immune-mediated diseases (IMDs). The primary objective of the panel was to assess areas of consensus on the IMD most prone to TE as well as modifiable and unmodifiable factors that might exacerbate or mitigate the risk of TEs.

Methods

Thirteen nationally recognized physicians were selected based on their contributions to guidelines, publications and patient care. The modified Delphi panel consisted of four rounds of engagement: (1) a semi-structured interview, (2) an expert panel questionnaire, (3) an in-person panel discussion, and (4) a consensus statement survey.

Results

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease were identified as two of four IMDs with the highest TE risk. Consensus was reached on several non-modifiable and modifiable characteristics of high-risk. Approaches to reduce TE incidence were identified such as altering treatment, requiring the monitoring of patients for TEs and modifying patient behaviors. Janus kinase inhibitors and corticosteroids were identified as therapies that required further evaluation given their potential TE risk.

Discussion

The panel reached a consensus that several IMDs are at an elevated risk of TEs. Physicians are unable to control most patient level risk factors but can control the therapies being used. Consequently, physicians should consider the specific IMD, be aware of TE risk factors, and take into account risk factors in selecting the therapies to optimally manage their conditions and to reduce the risk of TEs in this population.

1. Introduction

In the United States, the estimated prevalence of immune-mediated diseases (IMDs) is 5–8% of the populationCitation1,Citation2. Approximately 15–20 million individuals are affected by an IMD and taken altogether IMDS are the third leading cause of illness and mortalityCitation3–5. Given the chronic nature of most IMDs, they have a significant burden on healthcare resource utilization as well as economic and societal burdensCitation6. The estimated average total costs for treating IMDs in 2015 ranged between $20,000 and $28,000 USD per patientCitation7.

IMDs are characterized by chronic inflammation, which may lead to platelet aggregation and clot developmentCitation8. Thus, individuals with an IMD have a higher risk of developing thromboembolic events (TEs), which refer to the formation of a clot (thrombus) that breaks loose and is carried by the blood stream to plug another vessel, including deep venous thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), myocardial infarction (MI) and ischemic strokeCitation9,Citation10. In addition, the risk is higher especially among individuals with select IMDs such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, plaque psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)Citation10–12. In fact, the risks of stroke and MI among patients with IBD and RA are respectively 25% and 52% greater compared to those without an IMDCitation12,Citation13. It is important to highlight that the overall costs and challenges of managing patients with IMDs significantly increase when patients have multiple risk factors for developing TEs. Depending on the condition, the estimated annual treatment costs of treating venous thromboembolism (VTE) range from $7 to more than $12 billionCitation14,Citation15.

While studies have suggested IMDs as an independent risk factor for developing TEs, the potential relationship between IMDs and TEs is largely impacted by patient factors (e.g. age and sex) and medical historiesCitation8,Citation16. Individuals with IMDs generally have a baseline increased risk for TEs as they often present with complex comorbidities. Common comorbidities include smoking, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and physical inactivity, which further contribute to developing TEs as underlying risk factorsCitation16,Citation17. In addition, patients with a prior history of TEs carry an even greater risk of developing another TECitation17. The use of specific immunomodulatory medications, including certain Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKinibs), has been identified as an additional increased risk factor for TECitation18.

Given the growing prevalence of IMDs and the burdens they place, coupled with the added risk these patients face for a TE, it is important to our collective societal benefit to be thoughtful in managing these patients. To manage these patients, additional insights are needed particularly from physicians who have a great deal of experience treating IMD patients. Consequently, a modified Delphi panel was convened to gain the insights from a multidisciplinary group of physicians regarding their, as well as their colleagues’, understanding and awareness about the relationship between TE and IMD. Specifically, the panel addressed a number of questions including the following. Are there specific IMDs that are most prone to TEs? What can be done to reduce the risk of TEs in patients with IMD?

2. Methods

A modified version of the Delphi technique, a method for consensus-building that uses an iterative approach, was conducted among a group of physicians with expertise across multiple disciplinesCitation19. A modified Delphi study is derived from the original Delphi methodCitation19–22, which includes multiple rounds where participants respond to a questionnaire and return it to the researcher, after which the researcher edits and returns to every participant a statement of the position of the whole group and the participant’s own opinionCitation20. The respondents are then encouraged to reconsider their initial judgements about the information or questions provided in previous iterations. A common modification, which was used in the current study, is the introduction of a face-to-face meeting to facilitate discussion among the panelistsCitation21,Citation22. This hybrid approach combines the advantage of a structured Delphi approach with the advantages of a group discussion, namely the incorporation of many perspectives and clarification of the reasons for different perspectivesCitation23.

2.1. Panel selection

The multidisciplinary panel was recruited from a list totaling 162 healthcare providers (HCPs). This list was generated by identifying lead and senior author publications containing specific scientific keyword searches (“Venous Thromboembolism,” “VTE,” “Thromboembolic,” “JAK,” “TNF,” “S1P”) across seven specialties: gastroenterology, neurology, rheumatology, cardiology, pulmonology, hematology/oncology and dermatology. Additional ad-hoc searches were conducted via PubMed looking at national/international phase 3 clinical trials in the aforementioned specialties. Potential panelists were contacted and those with the relevant expertise and interest were invited to participate.

2.2. Rapid evidence review

A rapid evidence review (RER) was conducted that included a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH terms, [mh]) and key words (words in the title or abstract, [tiab]) related to autoimmune diseases and the drugs of interest (e.g. Janus Kinases/antagonists & inhibitors [mh], Embolism and Thrombosis [mh], “TNF inhibitor” [tiab]), and specific question areas such as prevalence or costs (e.g. epidemiology [mh]) or costs (e.g. Costs and cost analysis [mh], economics [mh], utilization [tiab]). All searches were conducted between June and August 2019. Given the volume of literature and the narrow time frame for the review, a “best evidence” approach was used, relying on better quality systematic reviews and meta-analyses where possible and supplementing with randomized trials or higher quality studies (e.g. large observational studies, databases analyses/”real world” analyses with larger, representative populations) where appropriate. A brief report was developed based on the RER and was sent to all panelists prior to the semi-structured interview.

2.3. Modified Delphi procedure

The modified Delphi technique comprised four iterative steps; each step informed the subsequent step. A brief description of these steps is provided below.

2.3.1. Semi-structured individual interviews

Semi-structured individual interviews via web-calls were conducted to collect qualitative insights from each panel member. Panel members were asked several open-ended questions including: (a) their experience with IMD patients; (b) their preferred treatment modalities; and (c) whether they thought IMD patients were at an increased risk of TE. The complete semi-structured interview guide is available in Supplementary Online Appendix A. Information received from the interviews was used to develop the Multidisciplinary Panel Questionnaire.

2.3.2. Multidisciplinary panel questionnaire

After the completion of the semi-structured interviews, panelists were sent a link to a questionnaire designed to further capture and quantify the insights provided in the interviews. As can be seen in Supplementary Online Appendix B, the questions assessed the panelists beliefs regarding the IMD patient population and risk of TEs, risk factors for TEs, and open-ended questions asking what steps could be taken to reduce the risk of TEs in the IMD patient population.

2.3.3. Multidisciplinary panel in-person meeting

An in-person meeting was convened which all panelists attended. At this meeting panelists were presented with an overview of the RER as well as the results from the multidisciplinary panel questionnaire. Large and small group discussion focused on the following topics: (a) IMDs most at risk for TEs; (b) modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for TEs; (c) current therapies for IMDs; and (d) TE risk associated with IMD therapies.

2.3.4. Consensus statement questionnaire

Following the in-person meeting, all panelists received a questionnaire that was completed online and contained 13 proposed consensus statements (See Supplementary Online Appendix C) based on the discussions that took place at the in-person meeting. Panelists indicated the extent they agreed with each statement using a Likert-type scale ranging from “1” (Strongly Disagree) to “5” (Strongly Agree). The consensus statements were developed based on the discussions during, and the themes that emerged from, the panel in-person meeting. The purpose was to determine whether the experts agreed with the statements and consensus could be reached.

3. Results

3.1. Panel characteristics

The multidisciplinary panel consisted of a total of 13 nationally recognized physicians from the fields of cardiology (n = 1), dermatology (n = 2), gastroenterology (n = 2), neurology (n = 2), pulmonology (n = 3) and rheumatology (n = 3).

3.2. Pre-meeting questionnaire

When asked if they agreed with the statement that all IMD patients were at a higher risk of TE compared to the general population, 62% (8 of the 13) of panelists either agreed or strongly agreed (mean = 2.85; SD = .80). When asked if all IMD patients across disease areas have a similar risk for TE only 15% (2 of 13) of the panelists agreed or strongly agreed.

With respect to the perceived risk of TE by disease area, both systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and ulcerative colitis (UC) had the greatest risk. In fact, 62% of the panelists indicated that SLE patients were at a “high risk” for TE while 55% indicated that UC patients were at a very high risk. Interestingly, when examining risk by specialty area (autoimmune experts n = 8; hematology experts) 100% of the clot experts rated SLE as high risk compared to 37% of the autoimmune experts. Similarly, 80% of the clot experts rated UC as a high risk for TE compared to 37% of the autoimmune experts.

Descriptive results for the items assessing risk of TE by specific patient characteristics indicated that patients that had a prior DVT or PE were both considered at the greatest risk for another TE. In fact, 85% (11 of 13) of the experts rated prior DVT or PE as a “high risk”. Other patient characteristics rated as relativity high included recent surgery, paralytic patients, cancer and limited mobility.

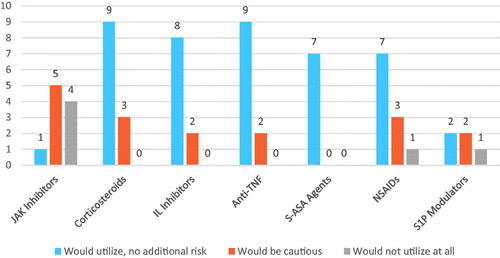

Finally, the descriptive results for the question assessing likelihood of utilization of different therapeutic agents in IMD patients is presented in . The majority of panelists indicated that that they would use corticosteroids, interleukin inhibitors, TNF inhibitors, 5-ASA agents and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Interestingly, 9 of the 10 panelists that answered the question indicated that they would be cautious when using JAKinibs.

3.3. Multidisciplinary panel in-person meeting

At the beginning of the in-person meeting, panelists nominated diseases they believed with the greatest chance for treatment to reduce the incidence of TEs, and the top four diseases nominated were SLE, RA, UC and Crohn’s disease.

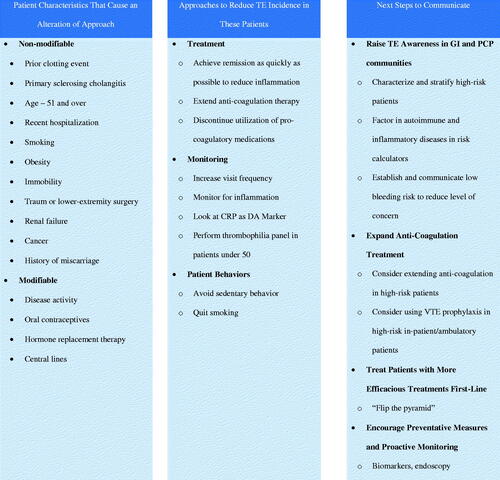

3.3.1. Discussion of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

With respect to UC and Crohn’s the panelists discussed (a) patient characteristics that would influence their treatment approach to minimize a TE; (b) approaches to reduce TE incidence in these patients; and (c) steps needed to communicate this risk to other HCPs (see for a summary). For patient characteristics, the experts identified a number of non-modifiable and modifiable characteristics. On the non-modifiable side, the most salient were prior clotting event, age, smoking and obesity. Modifiable risk factors included disease activity, the use of oral contraceptives, the use of hormone replacement therapy and central line use. For approaches to reduce TE incidence, the panelists recommended three broad approaches: (a) reduce risk through treatment of the underlying IMD and anti-coagulation therapy; (b) increased monitoring of patients; and (c) altering certain patient behaviors. Finally, panel experts recommended communication steps that included raising awareness of the TE in the gastrointestinal and primary care physician communities. They also suggested that the expansion of anti-coagulation treatment be suggested to the broader medical community. Experts also strongly suggested that more efficacious treatments of IMDs be used as first-line therapy. Finally, the experts suggested that physicians be encouraged to use more preventative measures and proactive monitoring of TEs.

3.3.2. Systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis

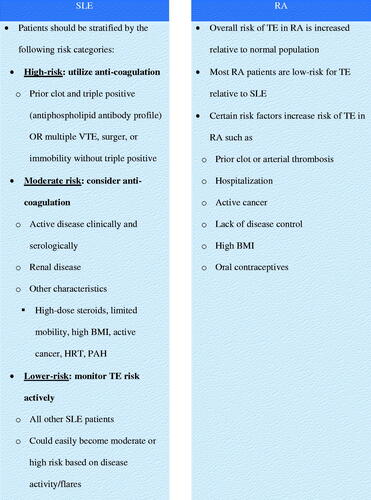

contains a summary of the expert panel discussion on SLE and RA. For SLE, the panel identified characteristics of patients that placed them at a high, moderate or low risk of TE. For high risk the most salient was a prior clot and triple positive (antiphospholipid antibody profile) as well as multiple VTEs, surgery, or immobility without triple positive. Patients at moderate risk were defined as those with clinically active IMD or renal disease. Low-risk patients included any other SLE patients, but it was noted that with the presence of active disease these patients could easily move to the moderate- or high-risk categories. For RA, the panel of experts recognized that this patient population was already at a significantly increased risk of a TE relative to the general population, but still at a lower risk than SLE patients. Additional patient characteristics that were identified include prior clot, hospitalization, cancer, active disease, obesity and immobility.

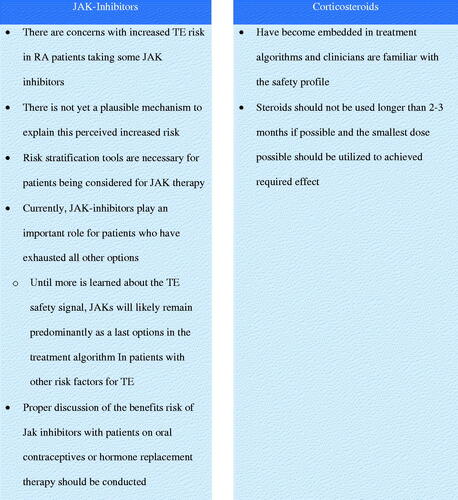

3.3.3. Treatment modalities that require closer evaluation

After discussing the various IMDs and their associated risk of TEs, discussion turned to identifying therapies for IMDs that might need a closer examination in light of potential TE risk (see ). A number of therapeutic approaches were mentioned including steroids, NSAIDs, P-glycoprotein (PGP) inhibitors and inducers, CYP3A inhibitors and inducers, JAKinibs, TNF-is, sIL-6R inhibitors. The panel agreed that both JAKinibs and corticosteroids were the two most important classes of drugs that needed further evaluation. The primary takeaway point from this discussion was that the mechanism linking JAKinibs to an increased TE risk is still unknown. Furthermore, JAKinibs are typically given as a later line therapy and that approach should remain until more is known about their TE risk. With respect to corticosteroids, the panel commented that even though they are linked to a higher risk of TE, they have been used for so long that they are embedded in the treatment algorithms. In addition, since their use is so ubiquitous, physicians know their safety profile and feel comfortable using them to treat many IMDs.

3.3.4. Consensus statements questionnaire

The results of the Consensus Statement Questionnaire are provided in . There was a high degree of agreement (>91%) across all the proposed consensus statements. In particular, 100% of the experts on the panel agreed that patients with an IMD are at a higher risk of TE compared to the general population, and certain classes of medications are associated with a higher risk of TE. Interestingly, most of the experts (93%) agreed that caution should be exercised when using certain classes of medications such as JAKinibs, but 100% said JAKinibs were a viable option for IMD patients and have a role in treatment algorithms particularly in patients when other options have been exhausted.

Table 1. Results from proposed consensus statement questionnaire.

4. Discussion

This paper presents the findings from the first modified Delphi panel technique to examine the risk of TEs in patients diagnosed with an IMD. Given that prevalence of IMDs is steadily increasing coupled with the fact that IMD patients are at a high risk for TEsCitation9,Citation24,Citation25, there is a growing need to further understand the connection between IMD and TEs.

The modified Delphi technique employed here provided a number of important insights. First, this panel of experts identified SLE, RA, UC and Crohn’s disease as the top IMDs where the risk of TE could be lowered. Interestingly, there were some differences between panelists with expertise in autoimmune disease and those with expertise in thrombolic disorders, Namely, the proportion of clotting experts that considered SLE and UC patients at high risk of TE was larger than the proportion of autoimmune experts that considered those patients high risk for TE. Second, prior DVT and PE were both considered by most experts as characteristics that placed patients at a particularly high risk for TE. Third, 50% of panelists stated they would be cautious when using JAKinibs and 40% would not use JAKinibs at all to treat IMD patients. JAKinibs and corticosteroids were two therapies that could benefit from additional research pertaining to their risk of TE. Fourth, experts placed emphasis on modifiable risk factors, particularly the selection of different therapies, in an attempt to mitigate the risk of TE. They also championed the notion that the risk of TE in these patient populations should be communicated more broadly across the medical field. Fifth, patient and disease characteristics that placed SLE and RA patients at varying degrees of TE risk were identified. Prior thromboembolic episode and uncontrolled disease activity were both identified as placing these patients at a higher risk for TE.

Results from the consensus statement questionnaire that panelists completed after the in-person meeting confirmed the themes that emerged throughout the previous steps of the modified Delphi technique. Specifically, the panelists agreed that the risk of TE is significantly higher in IMD patients and is particularly greater in specific IMDs such as SLE, IBD and RA. Furthermore, the panelists agreed that that certain therapies such as JAKinibs should be used with caution given their increased TE risk; however, all of the experts still maintained that they would continue to use JAKinibs despite this risk, particularly for patients who have exhausted other options.

While the results of this modified Delphi panel are important, they should be considered alongside some potential limitations. Though there is no generally agreed upon standard for sample sizes in Delphi studiesCitation26, a larger sample of experts would increase the reliability and generalizability of the study results. However, it is important to note that the current sample size does fall within the range of 10 to 18 panelists per domain of expertiseCitation27,Citation28. In addition, voting on consensus statements would have been ideally conducted at the in-person panel meeting, but due to logistical issues this was not possible. However, given the ease and prevalence of online questionnaires the panelists were able to complete the survey at home. While the experts included in this study all had experience with TEs, the panel did not included a hematologist which may have further deepened the study conclusions. The experts on this panel did not discuss whether the risk of TE is the same for JAKinibs. Future research will certainly have to explore this possibility in greater detail. Finally, this study did not include additional measures that could be used to establish the convergent or divergent validity of the consensus statement questionnaire.

With these limitations in mind it is still important to note that this modified Delphi panel has highlighted the need for additional research to examine the risk of TE in IMD patients. Robust, real-world data analysis using claims or medical record data is needed to further examine the link between TEs and various therapies such as JAKinibs and whether this link is moderated by specific IMDs. In addition, a better understanding of the basic epidemiology of TE and IMD is greatly needed. In addition, for patients with IBD, patients need prophylaxis when mobility is limited and especially in the setting of an admission with acute symptoms and a higher inflammatory burden. After an episode of DVT, long term anticoagulation should be considered, especially if there is a thrombophilia.

5. Conclusions

Patients with an IMD demonstrate an inherent higher risk of developing TE, which could be related to the systemic IMD and the complex association of inflammation with thromboembolic pathway. Potentially due to their intensive and extensive systemic impact some IMDs, such as SLE, RA, UC and CD, have been observed to have higher risk of TE than the others.

While physicians cannot control patient level risk factors, they can control what therapy is being used to minimize the risk of TE in the IMD patient population. There are clearly ways to mitigate the risks of TE that range from patient characteristics to using/changing therapy. Consequently, physicians need to have a heightened awareness of IMD patients with additional unmodifiable risk factors and should account for these risks factors when making their treatment decisions, particularly when considering therapies shown to add to the baseline risk of TEs.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Arena Pharmaceuticals.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

S.C. has disclosed that he has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Lilly and Gilead Pharmaceuticals. J.C. has disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Arena Pharmaceuticals. V.S. has disclosed that she has received consulting fees from Abbvie, Amgen Corporation, Arena, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Blackrock, Bioventus, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celltrion, Concentric Analgesics, Crescendo/Myriad Genetics, EMD Serono, Equilium, Eupraxia, Flexion, Galapagos, Genentech/Roche, Gilead, GSK, Horizon, Ichnos, Inmedix, Janssen, Kiniksa, Kypha, Lilly, Merck, MiMedx, MyoKardia, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Samsung, Samumed, Sandoz, Sanofi, Scipher, Servier, Setpoint, Tonix and UCB. J.W. has disclosed that he has received consulting fees and research support from AbbVie. A.Y. has disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Takeka and Arena Pharmaceuticals. No potential conflict of interest was reported by N.A., F.C., T.F., M.H., V.T. or A.W. CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (472.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jason Allaire PhD of Generativity Solutions Group for his assistance with editing the paper.

References

- Hayter SM, Cook MC. Updated assessment of the prevalence, spectrum and case definition of autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11(10):754–765.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) Autoimmune Diseases Coordinating Committee. Progress in Autoimmune Diseases Research (Publication No. 05–5140). Washington (DC); 2005.

- Wang L, Wang FS, Gershwin ME. Human autoimmune diseases: a comprehensive update. J Intern Med. 2015;278(4):369–395.

- Thomas SL, Griffiths C, Smeeth L, et al. Burden of mortality associated with autoimmune diseases among females in the United Kingdom. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2279–2287.

- Rose NR. Prediction and prevention of autoimmune disease in the 21st century: a review and preview. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183(5):403–406.

- Roberts MH, Erdei E. Comparative United States autoimmune disease rates for 2010–2016 by sex, geographic region, and race. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(1):102423.

- Schroeder KM, Gelwicks S, Naegeli AN, et al. Comparison of methods to estimate disease-related cost and healthcare resource utilization for autoimmune diseases in administrative claims databases. ClinicoEcon Outcomes Res. 2019;11:713–727.

- Ogdie A, Kay McGill N, Shin DB, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a general population-based cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(39):3608–3614.

- Borjas-Howard JF, Leeuw K, Rutgers A, et al. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in autoimmune diseases: a systematic review of the literature. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2019;45(2):141–149.

- Zöller B, Li X, Sundquist J, et al. Autoimmune diseases and venous thromboembolism: a review of the literature. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;2(3):171–183.

- Yuan M, Cao WF, Xie XF, et al. Relationship of atopic dermatitis with stroke and myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Medicine. 2018;97(49):e13512.

- Schieir O, Tosevski C, Glazier RH, et al. Incident myocardial infarction associated with major types of arthritis in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(8):1396–1404.

- Sun HH, Tian F. Inflammatory bowel disease and cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality: a meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25(15):1623–1631.

- Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56–e528.

- Grosse SD, Nelson RE, Nyarko KA, et al. The economic burden of incident venous thromboembolism in the United States: a review of estimated attributable healthcare costs. Thromb Res. 2016;137:3–10.

- Gregson J, Kaptoge S, Bolton T, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors associated with venous thromboembolism. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(2):163–173.

- Nagy G, Németh N, Buzás EI. Mechanisms of vascular comorbidity in autoimmune diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30(2):197–206.

- Verden A, Dimbil M, Kyle R, et al. Analysis of spontaneous postmarket case reports submitted to the FDA regarding thromboembolic adverse events and JAK inhibitors. Drug Saf. 2018;41(4):357–361.

- Yousuf MI. Using experts’ opinions through Delphi technique. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12(4):1–8.

- Hsu C-C, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12(10):1–8.

- Caporali R, Carletto A, Conti F, et al. Using a modified Delphi process to establish clinical consensus for the diagnosis, risk assessment and abatacept treatment in patients with aggressive rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35(5):772–776.

- Eubank BH, Mohtadi NG, Lafave MR, et al. Using the modified Delphi method to establish clinical consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with rotator cuff pathology. BMC Med Res Method. 2016;16(1):56.

- World Health Organization. WHO handbook for guideline development. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

- Dean SM, Abraham W. Venous thromboembolic disease in congestive heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2010;16(4):164–169.

- Sejrup JK, Børvik T, Grimnes G, et al. Myocardial infarction as a transient risk factor for incident venous thromboembolism: results from a population-based case-crossover study. Thromb Haemost. 2019;119(8):1358–1364.

- Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2:i–iv,1–88.

- Okoli C, Pawlowski S. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inform Manage. 2004;42(1):15–29.

- Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–1015.