Abstract

Objective

This study was conducted to capture the educational needs, perceptions, and perspectives of oncologists towards Compassionate Use Programs (CUPs) in Asia, with the aim of gathering insights related to unmet needs for physician and patient assistance.

Methods

The participants responded to a voluntary, self-administered, closed-ended questionnaire through an online platform between 29 April 2020 and 17 June 2020.

Results

A total of 111 oncologists provided informed consent to participate in the study. Of these, 102 respondents fully completed the questionnaire and were included in the analyses. Maximum respondents (35.3%) had 10–20 years of experience after specialization with 19.6, 23.5, and 21.6% respondents having <5, 5–10, and ≥20 years of experience, respectively. Practice type plays a statistically significant role in the awareness of the existing compassionate program (p = .0066). While many respondents seem clear on the application process for CUP set in place by pharmaceutical companies, a higher number of respondents are unclear about the country regulations and processes for applying to CUPs set in place by regulatory authorities. Most respondents (75.5%) reported that there are no resources or training provided to them regarding CUPs. There was a significant association between the clarity of the application process for CUP set in place by the sponsors and the number of applications submitted (p = .0321).

Conclusions

Our study brings light on various issues faced by physicians in accessing CUPs especially related to the lack of education and training on utilizing CUPs. There are significant unmet needs related to improving the clarity for the application process, providing resources and related training, particularly for oncologists who do not have previous experience with CUPs.

Background

Expanded access programs or early access programs (EAPs) comprise of legitimate and ethical routes for patients to access experimental drugsCitation1. Although the terminologies are often vague, in Asia, the term compassionate use program (CUP) generally refers to EAPs where the investigational product (IP) is provided free of cost by the sponsor to patients who do not have any commercially available viable treatment optionsCitation2,Citation3. These programs involve patients who do not have access to ongoing clinical trialsCitation3.

The eligibility criteria for CUPs are less rigorous compared with clinical trials and more aligned with the indication for which approval is soughtCitation4. These programs are usually implemented in the later stages of drug development, with most being initiated within six months preceding or following New Drug Application (NDA) submissionCitation5.

Compassionate use programs provide several benefits to key stakeholders. Terminally-ill patients can avail potentially life-saving drugs in an ethical and compliant mannerCitation6. A study conducted at a Cancer Centre in the United States showed that a significant proportion of patients who were accepted for EAP derived clinical benefit from experimental oncology medicationsCitation7. Hence, EAPs not only provide drug access to oncology patients but also hold promise for a possible cure for malignancies which are not responsive to available treatments. There is increasing evidence to suggest that novel matched therapies for these patients with tumors having specific alterations are associated with good clinical response. However, access to oncology experimental therapies is limited and often only through CUPsCitation8. EAPs also permit physicians to build considerable expertise on the IPCitation6.

Challenges to compassionate use programs

While pharmaceutical companies are under no legal obligation to arrange CUPs, many manufacturers do so on the grounds of humanity and public goodwillCitation9. However, in doing so, manufacturers attract considerable expense and impact on long-term commercial gains due to reduced third-party funding for accessCitation4. Apart from financial concerns, CUPs are fraught with several ethical, regulatory, and logistic challenges, including:

Cost of drugs: In CUP, the cost of the IP and running the program is borne entirely by the developerCitation10.

Lack of standard protocols: As guidance on patient selection is lacking, enrolment of patients is usually based on medical status, but sometimes even on a first-come, first-serve basisCitation11. Protocols are needed for safety reporting, data analysis, supply logistics, as well as a strategy to transition from IP to the commercial product.

Lack of information: While larger pharma companies have a CUP structure in place, and many others lack well-defined processesCitation12. It is seen that information regarding ongoing CUPs is hard to accessCitation13. Pharmaceutical companies are often in a dilemma on how to publicize CUPs without being accused of advertising for an unapproved productCitation14,Citation15. The CURE Act was legislated in the US to improve patient access to information on early access programs and improve transparency in the approval processCitation12.

Unequitable access: Patients are increasingly using online petitions and social media campaigns to gain access to experimental treatments, indirectly gathering attention expanded access policiesCitation12. Unfortunately, in the process, well-publicized campaigns get access while those who are not able to garner attention are left outCitation14.

Regulatory requirements: Country-specific regulations and requirements need to be considered while implementing CUPsCitation15. Though the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves more than 99% of the applications submitted for expanded access, there is a cumbersome regulatory process involvedCitation15. “Right to Try” law has been passed in several US states, which allows patients to bypass the FDA’s regulation to get access to experimental drugs in specific scenariosCitation12. There is a lack of specific regulations in Asia related to the compassionate use of drugs.

Physician responses: Awareness and perceptions of physicians towards CUP vary based on differences in culture and regulatory systems. Apart from the medical eligibility criteria, it is seen that physicians are frequently influenced by the administrative effort required, financial considerations, and their own perceptions of benefits and risksCitation16.

The way ahead for compassionate use programs

It has been suggested that CUPs should be planned as a part of the drug development process rather than being implemented based on needCitation13. There could be a reluctance to initiate CUPs in few instances as the incidence of adverse effects may affect the chances of regulatory approval, even though it is used in uncontrolled settingsCitation6,Citation13.

Obviously, there is no simple or standard solution to ensure scientific, ethical, and commercial harmony while planning and arranging CUPs. Engagement with stakeholders, e.g. clinicians involved in the process to understand the expectations, benefits, and limitations, can help to arrive at balanced solutionsCitation4. It is seen that physicians' attitudes play a significant role in the utilization of CUPs.

As CUPs are designed for medical conditions for which no feasible treatment options are commercially available, it is not surprising that almost 50% of approved expanded access programs involve oncologyCitation5. Hence, this study targets oncologists in particular, whose evaluations and inputs can play a crucial role in providing the relevant insights for targeted strategies to bridge physician needs and consequently benefit the patients. The objective of the study was to determine the educational needs, perception, and perspectives of oncologists related to compassionate use programs (CUPs) in selected countries from Asia.

Methods

Study population

The sample for the study was from oncologists from selected countries in Asia. Oncologists from Asia (Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand, and India) who have contacted Pfizer for information or interest in CUPs for any oncology-related programs. The scope of the study in Thailand was limited to participants from Siriraj hospital. The participants were selected at random for survey participation and were invited to fill out the self-administered questionnaire.

Inclusion criteria

Practicing oncologists who had contacted Pfizer for information or interest in CUPs.

Exclusion criteria

Inability to provide informed consent (e.g. language barriers and unavailability of an interpreter).

Incomplete/partially filled survey (exclusion was confirmed upon the discretion of the principal investigator).

Study procedure

Qualitative data were collected using an anonymous, online, structured, and self-administered closed-ended questionnaire rolled out using SurveyMonkey between 29 April 2020 and 17 June 2020. Frequent reminders were used to improve response rates and avoid non-response bias.

The survey questionnaire (Supplementary Appendix 1) consisted of a total of 13 items and comprised of three sub-scales: (i) “demographics and experience in practice and with CUP applications” (4 items), (ii) “educational needs” (3 items), and (iii) “perception and perspectives” (6 items).

Compliance with ethics of experimentation

The study was conducted in agreement with the guidelines and recommendations as defined by the 18th World Medical Assembly, Helsinki, 1964, and subsequent revisionsCitation17. The survey questionnaire (Supplementary Appendix 1) did not request any identifiable information, and all the data were collected anonymously. Potential study participants were appropriately informed about the purpose of the research survey and their scope of involvement. Participation was completely voluntary, and responses were collected anonymously with prior consent. Any form of financial incentives was not offered to study participants. The study falls under the general exemption for ethics committee (EC) approval in the countries where the study was conducted. The extracted guidance from country regulations regarding EC review is described below.

India: Research on anonymous or non-identified data/samples carries “less than minimal risk.” Research with less than minimal risk where there are no linked identifiers is exempted from the EC reviewCitation18.

Malaysia: Research involving the use of survey procedures (questionnaires), interview procedures, or observation of public behavior and with no collection of any identifiable private information is exempted from the EC reviewCitation19.

Singapore: Non-interventional studies with the use of non-identifiable data are outside the scope of “human biomedical research” and EC reviewCitation20.

Taiwan: Non-interventional studies without the involvement of an investigational product(s) are outside the scope of “clinical trial” and EC reviewCitation21.

Thailand: The scope of the study was limited to participants from Siriraj hospital. Our study falls outside the scope of types of research requiring EC approval for Siriraj hospitalCitation22.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed on the responses collected from the sub-scales on educational needs, perception, and perspectives. Additionally, “associations” between participants' “demographic data and experience” and the data collected from the last two sub-scales were assessed.

Statistical analysis

All data sets were categorical data. Descriptive statistics were carried out using frequency (percentage). Statistical significance for correlations of items in subscale 1 with items in subscale two and subscale three was derived using Fisher Exact test. All p-values were tested considering a 5% level of significance and considered as statistically significant for p ≤ .05. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS Software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

A total of 111 oncologists provided informed consent and agreed to participate in the study. Of these, 102 respondents from Singapore (16.67%), Malaysia (14.71%), Thailand (5.88%), Taiwan (16.67%), and India (46.08%) fully completed the questionnaire and were included in the analyses. The percentage of respondents working in public health, private healthcare and both were 38.24, 53.92, and 7.84%, respectively. Experience after specialization was <5, 5–10, 10–20, and ≥20 years in 19.61, 23.54, 35.29, and 21.57% of respondents, respectively. Response data for the key question items is as mentioned in .

Table 1. Response data for the key question items (N = 102).

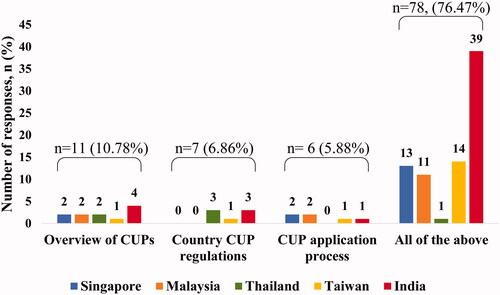

Most respondents (75.5%) reported that there were no resources or training provided to them regarding CUPs. While 73% of respondents seemed clear on the application process for CUP set in place by pharmaceutical companies, 55% reported clarity on country regulations and processes for applying to CUPs set in place by country’s regulatory authorities. The majority believe that a systematic educational model would be helpful. Within each country, the most common response from most of the countries was in favor of a complete educational model including an overview of compassionate use programs, country CUP regulations overview, and CUP application process ().

Figure 1. Country-wise preference for the content of educational modules. The majority (76.5%) of the respondents favored a complete educational module on CUPs, covering an overview of CUPs, country-specific CUP regulations, and the application process. Though country-wise response rates on preference for content were different, an inter-country comparison could not be performed as sample sizes across the countries were highly variable.

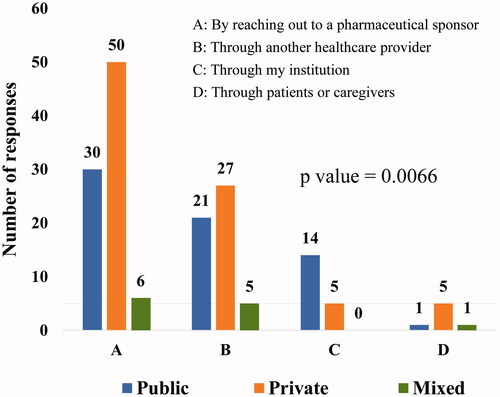

Practice type was found to play a statistically significant role in the awareness of existing CUPs (p = .0066). Among all the available sources of information about existing CUP, “by reaching out to the pharmaceutical sponsor” was the most common route for oncologists to get to know about an existing CUP. Physicians from practice in public healthcare seemed to be more aware of existing CUPs through their institutions than physicians from private or mixed practice ().

Figure 2. Source of awareness on existing CUPs based on the type of clinical practice. Type of clinical practice plays a statistically significant role in awareness regarding existing CUPs (p=.0066). Reaching out to a pharmaceutical sponsor was the most favored method of gaining awareness by oncologists across all types of clinical practices (multiple options were permitted for selection of the response). Public, public/government hospital/clinic; private, private hospital/clinic; mixed, both public and private hospitals/clinics

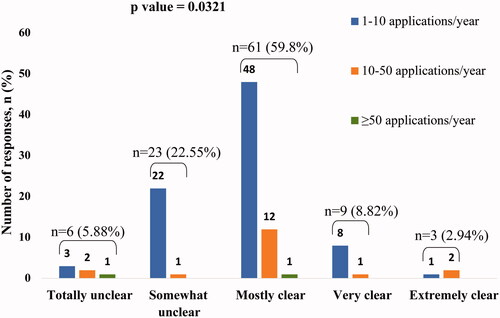

There was a significant association between the clarity of the application process for CUP set in place by the sponsors and the number of applications submitted (p = .0321). Participants with the response as “mostly clear” to the question on the clarity of application process set in place by pharmaceutical sponsors for applying for CUPs submitted the highest number of applications to pharmaceutical companies, over last 12 months ().

Figure 3. Association between clarity of application process and number of applications submitted for CUP over the last 12 months. The number of applications submitted was significantly associated with the clarity of the application process for CUP set in place by pharmaceutical sponsors (p=.0321). Participants with the response as "mostly clear" submitted the highest number of applications to pharmaceutical companies over the last 12 months.

Discussion

The results of our study bring forth the challenges faced by physicians in accessing CUPs. The key issue highlighted by respondents in the study was the lack of education and training on utilizing CUPs. There seems to be a need for the regulations and the processes to be set more clearly. Addressing the issue and improving physician awareness regarding the application process for CUPs can serve to improve the outreach of these programs and, eventually, patient access.

A similar study by Moerdler et al. evaluated the experiences of pediatric oncologists with applying for and obtaining access to CUPs. Access to CUPs is all the more critical in pediatric patients as most clinical trials do not enroll patients less than 18 years, even when there is a potential for efficacy. However, only 37% of respondents in the study considered themselves as competent or very competent in obtaining approval from pharmaceutical companies for the use of an investigational drug. The study concluded that participation in CUPs is influenced by physician's experience in clinical practice, size of institution, and availability of educational resources and administrative supportCitation23. The most common challenges to the utilization of CUPs reported were the inability to identify a drug with potential efficacy and lack of understanding and knowledge of the application processCitation23.

The importance of simplifying the application process and providing guidance on CUPs is demonstrated by the success of FDA initiatives in this regard. The FDA has been supportive of the compassionate use of drugs to eligible patients. In a step aimed at helping oncologists with the application process, Project Facilitate was launched on 31 May 2019. Under the aegis of this project, a call center was set up to guide oncologists through the expanded access process and collect data provided by oncologists on outcomes of expanded application. In the initial 3 months itself, there was a 20% increase in the number of applications for oncology drugs received by the agency compared to the same period in the previous year. Apart from Project Facilitate, the FDA.gov website also provides information, including relevant FDA contact information, to assist in applying for expanded access to investigational drugs in other disease areasCitation24. Similar initiatives may help other parts of the world.

The Moerdler study also showed an increased likelihood of success of the CUP process among physicians who had a point of contact at the pharmaceutical companyCitation23. Most pharmaceutical companies are increasingly making information and policies about their CUPs available on their websites in compliance with the “twenty first Century Cures Act” which was passed in December 2016. Transparency and access to information can significantly simplify the application process, ensuring wider access to CUPsCitation23.

There are examples where pharmaceutical companies are working towards making the CUP process more transparent by not only setting up an independent Compassionate Use Advisory Committee consisting of physicians, bioethicists, patients, and patient advocates but also including an appeal process for physicians whose requests for CUP were deniedCitation25.

However, despite the existing efforts by regulators and manufacturers, lengthy and cumbersome CUP application procedures, delayed timelines in approval often discourage physicians from applying for CUPs. This is especially relevant for cancer-related treatment where the tumor may have progressed by the time the CUP medication is approved, and the patient may then be ineligible to receive the approved CUP treatment. Services that help navigate through the complicated application process would also be welcomed by physicians who are often intimidated by the long-drawn process and lack of resources and time to invest in the sameCitation24. Eighty-three respondents of a survey reported that having a support service to take care of the paperwork and provide assistance with the use of CUP would be helpfulCitation23. The non-profit organization Kids v Cancer developed the Compassionate Use Navigator to assist physicians and families in applying for experimental drugs. It provides live assistance, templates, and guidance on the application process. It also offers relevant contacts at the FDA, pharmaceutical company, or the Institutional Review Boards. Further, it also collects outcomes data from physicians and families and provides physicians with resources on safety monitoring and adverse event reporting on using the drugCitation23,Citation26. With similar goals in focus, the FDA has launched the Expanded Access Navigator in partnership with patient advocacy groups, the pharmaceutical industry, and the federal government to provide clear guidance on single-patient EAPsCitation27. Services such as these offer a one-stop resource for navigating the application process for CUPsCitation26.

While the results of this study highlight the gaps in accessing CUPs encountered by physicians, it is limited by the relatively small sample size. Further, the study respondents were representative of only a few Asian countries. Of these, a disproportionately large subset was from India, which is burdened with a large population and an under-developed healthcare system. The high load of patients, lack of resources, and time-constraints might have contributed to bias in this subset. Hence, further surveys are warranted to elicit the challenges in the utilization of CUPs and mitigate them.

Though all the stakeholders involved in the CUP planning and execution are stepping up to resolve challenges to CUPs, a lot remains to be done. Requests for participating in CUP have been increasing in recent years, necessitating proper protocols to handle the increased demandCitation15. Physicians need to be educated on availability and processes in accessing CUPs through webinars and continuing medical education. Developers have been urged to make information on CUP programs, indications for IP and contact details of personnel handling CUP available on their websitesCitation13. Initiatives from all stakeholders can help to improve the accessibility of CUPs and extend their benefits to a larger number of eligible patients.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The study was funded by Pfizer. Data analytics and medical writing support were provided by Transform Medical Communications, which was also funded by Pfizer.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

All authors are employees of Pfizer. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work. The results and discussions in this article do not represent or reflect in any way the official policy or position of the current or previous employers of the authors. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material: Appendix 1 Questionnaire CUP Survey

Download MS Word (36.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely appreciate the medical writing support provided by Dr Sajita Setia, Executive Director, Transform Medical Communications, Auckland, New Zealand, and editorial support provided by Dr. Veena Angle, Singapore, on behalf of Transform Medical Communications.

References

- Iudicello A, Alberghini L, Benini G, et al. Expanded access programme: looking for a common definition. Trials. 2016;17(1):21.

- Jarow JP, Lurie P, Ikenberry SC, et al. Overview of FDA's expanded access program for investigational drugs. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2017;51(2):177–179.

- Setia S, Ryan NJ, Nair PS, et al. Evolving role of pharmaceutical physicians in medical evidence and education. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:777–790.

- Lewis JR, Lipworth W, Kerridge I, et al. Dilemmas in the compassionate supply of investigational cancer drugs. Intern Med J. 2014;44(9):841–845.

- Puthumana J, Miller JE, Kim J, et al. Availability of investigational medicines through the US Food and Drug Administration's expanded access and compassionate use programs. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180283.

- Patil S. Early access programs: benefits, challenges, and key considerations for successful implementation. Perspect Clin Res. 2016; 7(1):4–8.

- Feit NZ, Goldman DA, Smith E, et al. Use, safety, and efficacy of single-patient use of the US Food and Drug Administration Expanded Access Program. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(4):570–572.

- Fountzilas E, Said R, Tsimberidou AM. Expanded access to investigational drugs: balancing patient safety with potential therapeutic benefits. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2018;27(2):155–162.

- Mackey TK, Schoenfeld VJ. Going “social” to access experimental and potentially life-saving treatment: an assessment of the policy and online patient advocacy environment for expanded access. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):17.

- Miller JE, Ross JS, Moch KI, et al. Characterizing expanded access and compassionate use programs for experimental drugs. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):350.

- Caplan AL, Teagarden JR, Kearns L, et al. Fair, just and compassionate: a pilot for making allocation decisions for patients requesting experimental drugs outside of clinical trials. J Med Ethics. 2018;44(11):761–767.

- Mackey TK, Schoenfeld VJ. Going “social” to access experimental and potentially life-saving treatment: an assessment of the policy and online patient advocacy environment for expanded access. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):17.

- Medscape. How to improve access to compassionate-use drugs [Internet]. Medscape; 2015 [cited 2020 Oct 19]. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/854706.

- Raus K. An analysis of common ethical justifications for compassionate use programs for experimental drugs. BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17(1):60.

- Enterline L, Antoun M, Joines J. Access options for investigational products [Internet]; 2017 [cited 2020 Oct 19]. Available from: https://www.evidera.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Access-Options-for-Investigational-Products.pdf.

- Bunnik E, Aarts N, van de Vathorst S. Views and experiences of physicians in expanded access to investigational views and experiences of physicians in expanded access to investigational drugs. Clin Ther. 2017;39(8):e96.

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–2194.

- Indian Council of Medical Research. National ethical guidelines for biomedical and health research involving human participants [Internet]; 2017 [cited 2020 Oct 19]. Available from: https://main.icmr.nic.in/sites/default/files/guidelines/ICMR_Ethical_Guidelines_2017.pdf.

- Guidelines for ethical review of clinical research or research involving human subjects [Internet]. Medical Review and Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2006. [cited 2020 Oct 19]. Available from: http://www.nccr.gov.my/index.cfm?menuid=26&parentid=17.

- Human Biomedical Research Act [Internet]. Singapore Statutes Online; 2015 [cited 2020 Oct 19]. Available from: https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/HBRA2015.

- Regulations for good clinical practice [Internet]. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of China; 2014. [cited 2020 Oct 19]. Available from: https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=L0030056.

- A researcher handbook for SIRB approval [Internet]. Siriraj Institutional Review Board; 2014. Available from: https://www.si.mahidol.ac.th/sirb/Eng/index.html.

- Moerdler S, Zhang L, Gerasimov E, et al. Physician perspectives on compassionate use in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(3):e27545.

- Gerasimov E, Donoghue M, Bilenker J, et al. Before it's too late: multistakeholder perspectives on compassionate access to investigational drugs for pediatric patients with cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2020;40:1–e227.

- Caplan AL, Ray A. The ethical challenges of compassionate use. JAMA. 2016;315(10):979–980.

- Compassionate use navigator [Internet]. Washington: KidsvCancer; 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 19]. Available from: https://www.kidsvcancer.org/compassionate-use/.

- The EA navigator mission [Internet]. Washington: Reagan-Udall Foundation [cited 2020 Oct 19]. Available from: https://navigator.reaganudall.org/expanded-access-navigator.