Abstract

Objective

Serious mental illnesses (SMIs), including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder (MDD), are often treated with antipsychotic medications. Unfortunately, medication non-adherence is widespread and is associated with serious adverse outcomes. However, little real-world data are available describing adherence, compliance, or other medication-taking–related discussions between providers and patients. This study described these communications in ambulatory care.

Methods

Commercially insured patients having acute (emergency or inpatient) behavioral health (BH) events were included by specific criteria: age 18–65 years; diagnoses of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or MDD; continuous health insurance coverage 6 months before to 12 months after the first claim (index) date during 01/01/2014‒12/31/2015; and prescribed antipsychotic medication. Medical charts were abstracted for ambulatory visits with a BH diagnosis through 12 months after the acute event, describing any treatment compliance discussions that occurred. BH-related healthcare utilization and costs were measured via insurance claims. Results were analyzed by observation of an antipsychotic medication taking-related (i.e. compliance or adherence) discussion at the initial abstracted visit.

Results

Ninety patients were included: 62% female, mean age 41 years. Only 58% had antipsychotic compliance discussions during the first abstracted ambulatory visit. A total of 680 BH-related visits were abstracted for the 90 patients. Providers frequently discussed any psychotropic medication use (97% of all visits abstracted); however, discussion of compliance with BH talk therapies was less common (49% of visits among patients with a first visit antipsychotic discussion and 23% without, p < .001). Follow-up BH-related healthcare utilization and costs were not significantly different by cohort. Patients with ≥2 compliance discussions had a significantly lower risk of follow-up acute events, which are the costliest components of healthcare for SMI (p = .023).

Conclusion

Increasing the frequency of antipsychotic treatment-related adherence/compliance discussions may represent an opportunity to improve the quality of care for these vulnerable patients and reduce the overall economic burden associated with the treatment of SMI diagnosis.

Introduction

Among the most costly and debilitating health conditions are serious mental illnesses (SMIs), including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder (MDD), which contribute substantially to disability and premature mortalityCitation1. The global total costs of mental illness in 2010 were $2.5 trillion (greater than the costs of cancer, diabetes, and respiratory diseases combined) and that burden is expected to rise to $6.0 trillion by 2030Citation2. In the US alone, for the more than 10 million adults who have an SMI diagnosis, the total direct and indirect economic burden is as high as $500 billion per yearCitation3–5.

Treatments for SMIs are most effective when patients are actively engaged in the management of their condition, including regular interaction with a clinical professional and adherence to (or compliance with) the prescribed treatment regimenCitation6–8, which often includes antipsychotic medication. Unfortunately, medication non-adherence is widespread among patients with SMI, with prevalence estimates ranging from 35% to 75% among systematic reviewsCitation9–11. The likelihood of poor medication adherence among patients with SMI may be increased by cognitive impairment, comorbid psychiatric conditions, and unpleasant side effects of psychotropic medicationsCitation12–14. Whatever the reasons for non-adherence, it has been associated with serious adverse outcomes, including relapse and reduced treatment response, and increased hospitalization risk, in addition to higher cost of careCitation15–19. Interventions that address non-adherence in this patient population may improve clinical outcomes. In clinical practice, provider insight into patient compliance with the treatment regimen influences treatment decisions. A full understanding of patient compliance with pharmacotherapy may prevent unnecessary therapy augmentations or allow ineffective medications to be switched more quicklyCitation20,Citation21.

Although results from modeling studies suggest that improving medication-related treatment compliance and increasing providers’ understanding of adherence among their patients with SMI could lead to substantial healthcare cost savingsCitation22,Citation23, little real-world data are available regarding the economic effects of treatment compliance–related discussions between providers and patientsCitation24. The purpose of this study was to describe the relationship between observation of documented provider/patient communication regarding medication treatment adherence or compliance on healthcare resource utilization and costs among patients being treated for SMI.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This was a retrospective study conducted using healthcare claims data from the Optum Research Database (ORD) linked with abstracted medical chart data to form an analytic dataset that included administrative and clinical data. The ORD is geographically diverse across the United States (US) and contains de-identified medical and pharmacy claims data with linked enrollment information for commercially insured individuals. Medical claims include diagnosis and procedure codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revisions, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM); Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes; site of service codes; and paid amounts. Pharmacy claims include drug name, National Drug Code (NDC), dosage, drug strength and form, fill date, number of days’ supply, and financial information for outpatient pharmacy services. This study was approved by the New England Institutional Review Board (#120170201), including a waiver of authorization under CFR164.512i.

Patient selection

Commercially insured patients with evidence of acute behavioral health (BH) treatment (identified by an emergency department [ED] visit or inpatient hospitalization) were identified using data from 01 January 2014 through 31 December 2015 (identification period).

Patients were included based upon the following criteria: Their age was 18–65 years during the identification period; they had claims-based evidence of an ED visit or inpatient hospitalization (acute event) with a diagnosis code of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or MDD () during the identification period; and they were continuously enrolled in health insurance coverage with medical and pharmacy benefits during the baseline and follow-up periods (meaning there were no gaps in health insurance coverage and all submitted and reimbursable medical and pharmacy services were observable for inclusion in the study).

The date of the first eligible acute BH treatment claim during the identification period was defined as the event index date. The baseline period was defined as the 6 months immediately prior to the index date. The follow-up period was defined as the 12 months following and including the index date for claims data, and up to 12 months after the first abstracted office visit for medical chart data. The observation period was unique to each patient.

In addition, patients were required to have at least 1 claim for an antipsychotic medication (aripiprazole, asenapine maleate, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, chlorpromazine, clozapine, droperidol, fluphenazine, haloperidol, iIoperidone, loxapine, lurasidone, mesoridazine besylate, molindone, olanzapine, paliperidone, perphenazine, pimavanserin tartrate, pimozide, prochlorperazine, promazine, quetiapine fumarate, risperidone, thioridazine, thiothixene, trifluoperazine, and ziprasidone) during the baseline period and within 60 d after the index date (minimum of 2 claims). Multiple claims were not required to be for the same medication. These inclusion criteria were selected specifically to identify patients with severe symptoms (with diagnosed MDD, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia) for whom treatment compliance was critical to avoid future acute events. Patients were not excluded if claims for alternative classes of psychotropic therapies, such as antidepressants were also observed.

Exclusion criteria were applied as follows: Patients with a primary diagnosis of interest but no evidence of follow-up ambulatory treatment were excluded. In order to select patients for whom SMI was the primary focus, patients were excluded by the presence of claims for substance abuse treatment in the baseline period or evidence of substance abuse treatment in the medical chart during 90 d prior to the index event. Patients with residential BH treatment on or within 2 d after the index event were also excluded because their medication adherence would have been controlled by the treatment program.

Medical chart abstraction and cohort assignment

Providers of patients meeting the study criteria were contacted for participation in the medical chart abstraction process. Medical chart data supplied by participating providers were abstracted, starting from the date of the first ambulatory visit with a BH diagnosis through up to 12 months follow-up. Provider participation in the medical chart abstraction process was voluntary and not all providers who were contacted opted to participate by providing the chart for inclusion. All visits in the chart that included BH treatment during the follow-up period were abstracted for each patient.

Antipsychotic medication taking, adherence or compliance-related discussions were identified from abstracted medical chart data using predetermined specific terms (“compliance,” “persistence,” and “adherence”), as well as nonspecific or general words and phrases identified as relating to compliance, persistence, and adherence (e.g. “continue taking medications” or “take medications as directed”). For purposes of this study, adherence/compliance/persistence are used interchangeably throughout to describe discussions. Patients were assigned to study cohorts (compliance not discussed vs compliance discussed) based on whether there was documentation in the patient’s medical chart of a medication-taking-related discussion, specific to antipsychotic medication taking, during the first abstracted visit after the index date. While cohort assignment was established using the first observed visit after the index date, medication-taking-related discussions that occurred during subsequent visits were also captured.

The abstracted medical chart data included all BH-related encounters between the patient and the provider of interest during the observation period. Analyses considered only the visit that occurred most proximal to the index event for each patient (first abstracted visit after the index event) and all abstracted visits (all visits). The analysis was stratified in this manner to enhance understanding of the patient experience soon after an acute event versus provider encounters that may occur later.

Study measures

Patient characteristics obtained from claims as of the index date included demographic information (age, sex and geographic location). Clinical characteristics obtained from claims were obtained for the 6-month baseline period, including the Quan–Charlson comorbidity scoreCitation25, which represents a method of measuring the burden of disease originally created to predict in-hospital mortality. Comorbid conditions of interest were identified using the Clinical Classifications Software managed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)Citation26. This measure generates indicator variables for specific disease conditions based on ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes. The most frequent comorbid conditions, as well as pre-specified conditions highly comorbid with SMI and antipsychotic therapies (such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia and heart failure), were presented. Finally, a count of the number of unique BH diagnoses was determined for the baseline and follow-up periods. These were counted by seven diagnosis categories (Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders [ADD/ADHD], adjustment disorder, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, depressive disorder, personality disorder, and schizophrenia), not by individual ICD-9/ICD-10 diagnosis codes. For example, a patient may have had two different depression diagnoses (e.g. F322 and F339), however, these would only count as 1 BH condition. The range for this count variable was 0–7.

The characteristics of abstracted office visits were obtained from chart data: these included the reason for visit; types of treatment discussed (antipsychotic medication or other treatments); treating provider specialty (for any visit); consultation with other providers; changes to the treatment regimen during the visit (occurrence and type); and instruction to return for a future visit. From medical charts, the time to first abstracted visit (the number of days from the end of the index event [for example, hospitalization discharge] to the date of the first visit abstracted) was determined.

Finally, characteristics of compliance/adherence to treatment-related discussions observed in medical chart documentation during abstracted office visits were recorded. These included count and proportion of visits at which treatment adherence/compliance was discussed using specific or nonspecific terms as described in the Methods. Treatment adherence/compliance-related discussions were characterized at the patient level and the visit level.

Outcomes

BH-related healthcare resource utilization and costs were measured for the baseline and follow-up periods with data obtained via claims. BH-related healthcare resource utilization was calculated for ambulatory visits, ED visits, inpatient admissions, and the pharmacy fill. BH-related visits and admissions were identified on the basis of claims with a BH-related diagnosis code (ADD/ADHD, adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorders, depressive disorders, personality disorders, and schizophrenia) in the primary diagnosis position. These codes intentionally represent a broader set of diagnoses than the three specified in the initial inclusion criteria, in order to capture all BH-related healthcare use and costs after the index event. Claims with diagnosis codes for cognitive (e.g. Alzheimer's disease and other dementias) and/or developmental disorders were excluded from the BH-related definition.

BH-related medication use was identified on the basis of pharmacy claims with NDCs and HCPCS codes for psychotropic medications (antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and anti-anxiety medications). BH-related healthcare costs for ambulatory visits, ED visits, inpatient admissions, other medical costs, and pharmacy use were calculated as combined health plan– and patient-paid amounts adjusted to 2017 US dollars using the annual medical care component of the Consumer Price IndexCitation27.

Statistical analysis

Results were stratified by study cohort (patients with antipsychotic adherence/compliance discussed vs. not discussed, at initial post-index visit), with frequency (n) and proportion (%) provided for categorical variables and means and standard deviations (SDs) provided for continuous variables. Between-cohort differences in patient characteristics and study outcomes were analyzed using t-tests and Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate.

A Cox proportional-hazards regression model was constructed to analyze time to a subsequent BH-related acute event (inpatient admission or ED visit with a BH primary diagnosis). The model examined time to first post-index acute BH event observed in the claims data. Time to the post-index event in days was measured for each patient. The primary time-dependent covariate was the count of antipsychotic medication compliance discussions which was modeled as a binary variable. Different cut points for the count of discussions were evaluated in the model independently, with the final model based on a cut point of 2 or greater discussions. The presence of a BH-related inpatient stay in the baseline period was included as a secondary covariate to control for readmissions among a population at high risk for inpatient or ED careCitation28. Controlling for baseline acute care events enables a better understanding of the impact of compliance discussions among patients who are frequent utilizers of acute careCitation29. Multicollinearity diagnostics were assessed by examining the variance inflation factor; all values were <10. Hazard ratios, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values were calculated for each independent variable. Patients who remained event-free (no acute BH-related inpatient admissions or ED visits after the index event) were censored at the end of the study period.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

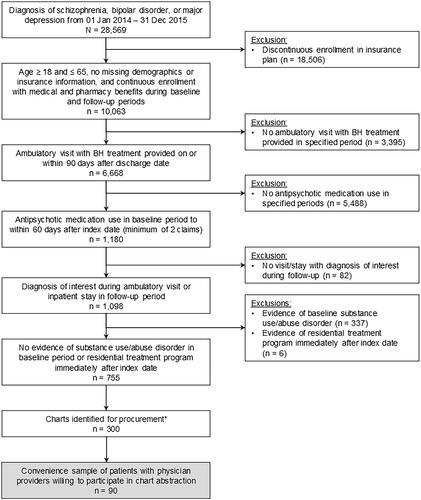

A total of 755 patients met the claims-based inclusion criteria (). Of those, a stratified sample of 300 patients was identified for medical chart procurement. The sample included all patients identified with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (n = 77) from the claims data; additional patients with diagnoses of bipolar disorder (n = 120) or MDD (n = 103) were randomly selected according to the natural distribution of patients with these diagnoses observed in the data to reach the planned sample of 300. Of the 300 identified whose providers were contacted for participation, the medical charts of 90 eligible patients were procured from the targeted providers, abstracted, and the abstracted chart data linked with administrative claims data.

Figure 1. Patient selection and attrition. *All patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia identified in the claims data (n = 77) were included in this selection. The remaining sample was selected from patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (n = 120) or major depression (n = 103). Abbreviations: BH = behavioral health.

More than half (62%) of patients included in the final analytic dataset were female, with a mean age of approximately 41 years (). Patients predominately resided in the South and Midwest regions of the United States. As expected, BH conditions represented the most common conditions identified from baseline claims: a mean and standard deviation (SD) of 1.4 (0.8) BH diagnoses were observed among all patients. In the abstracted medical chart data, bipolar disorder and MDD were the most common co-occurring diagnoses followed by generalized anxiety disorder/other anxiety disorders (63%) and attention deficit disorders (ADD/ADHD; 29%).

Table 1. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics from claims data.

Patients were stratified into cohorts by evidence of an antipsychotic medication-taking-related discussion during the first abstracted visit after the index date. Nearly 60% of patients (n = 52; 58%) had evidence of an antipsychotic treatment adherence/compliance-related discussion observed in the chart, using both general words for a medication-taking discussion and specific words (adherence, compliance and persistence), during the first abstracted visit.

Significant differences between cohorts were observed for key comorbid conditions. Among patients who did not have an antipsychotic medication use-related discussion, using general terms, at the first post-index visit, 39% had diagnoses of schizophrenia during the baseline period (vs. 17% among patients with such discussions; p = .029). Those who did not have medication use-related adherence/compliance discussion also had a higher rate of disorders of lipid metabolism (p < .05) and diabetes mellitus without complications (p < .05) than patients who did have such discussions. The cohorts were otherwise similar.

There were a total of 680 BH-related visits among the 90 patients’ abstracted medical chart data (). Overwhelmingly, visits included interaction with a physician (81%). When all abstracted visits were analyzed, treatment compliance was discussed more frequently among the cohort whose first visit included a discussion about antipsychotic medication, although the difference was not statistically significant (p = .058). A significant difference was observed in adherence/compliance discussions about behavioral health talk therapy after the first visit between those who did not (23%) and those who did (49%; p < .001) have an initial antipsychotic medication use-related adherence/compliance discussion.

Table 2. Characteristics of abstracted office visits occurring after the first post-index visit.

When antipsychotic treatment adherence/compliance was discussed during the first abstracted visit after index, the abstracted medical chart included numerically more visits (8.0 vs. 6.9, p = .230) and patients had a shorter mean (SD) time from the end of the index event to the first abstracted visit (29 [34] days vs. 45 [69] days, p = .202) although the differences were not statistically significant.

Patients whose first abstracted visit did not include an antipsychotic compliance discussion were more likely to experience a change in treatment (p = .003), including an increase in the dose of psychotropic medication (p = .040) when all abstracted visits were considered. These same patients were less likely to be told to return to their provider for a future visit (58% vs. 87%, p = .003 for first visits, 73.1% vs. 91.3%, p < .001 for all visits).

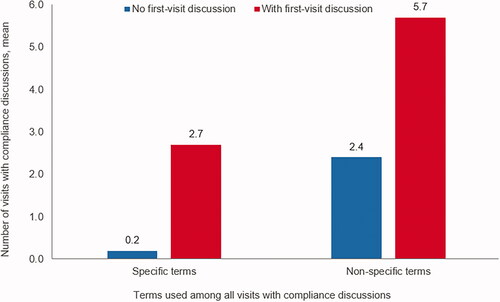

When antipsychotic medication use-related adherence/compliance was discussed with a patient during the first abstracted visit, the patient had more subsequent visits and those visits were more likely to include a compliance discussion. Patients without a compliance discussion during the first visit had significantly fewer subsequent visits with a treatment compliance discussion using specific terms (0.2 visits versus 2.7 visits, p < .001) or nonspecific terms (2.4 visits versus 5.7 visits, p < .001) ().

Figure 2. Number among all visits with medication compliance discussions, using specific or nonspecific terms, by the presence of first-visit compliance discussiona. aCompliance discussion = observation of general or specific words in the medical chart that indicate that discussion of medication-taking behavior was observed

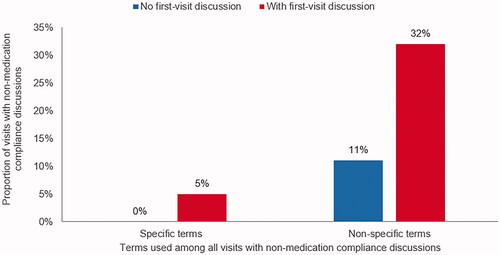

Among all abstracted visits, treatment compliance discussions regarding non-medication BH treatments were not common, even among patients whose first visit included a discussion of antipsychotic medication compliance: using specific compliance terms, only 5% (vs. 0% without first-visit compliance discussions); using nonspecific terms, 32% (vs. 11% without first-visit medication compliance discussions) ().

Figure 3. Proportion among all visits with non-medication treatment compliance, using specific or nonspecific terms, by the presence of first-visit medication compliance discussiona. aCompliance discussion = observation of general or specific words in the medical chart that indicate that discussion of medication-taking behavior was observed

BH-related utilization was high among the study population regardless of medication use-related discussion stratification, likely a result of the inclusion criteria which selected patients based on acute utilization of services. BH-related healthcare resource utilization did not differ during the 6-month baseline or the 12-month follow-up period ().

Table 3. Behavioral health-related healthcare resource utilization.

Like BH-related healthcare resource utilization, BH-related healthcare costs did not differ during the 6-month baseline or the 12-month follow-up period (). Among patients where compliance was discussed, however, costs were descriptively higher which is consistent with the higher number of abstracted visits among these patients.

Table 4. Behavioral health-related healthcare costs.

The relationship between antipsychotic treatment adherence/compliance-related discussions and follow-up acute BH-related events was tested using a Cox proportional-hazards regression model with >680 observations, adjusting for a baseline BH-related inpatient admission (). Patients with ≥2 compliance discussions had a 76% reduced risk of an acute event during the follow-up period, as compared to patients with fewer than 2 compliance discussions (HR = 0.239; 95% CI = 0.070–0.818; p = .023). Two patients with an event were excluded from the analysis because the event occurred prior to their first abstracted visit and consequently, the opportunity for a compliance-related discussion had not yet occurred.

Table 5. Cox proportional hazards analysis of time to first behavioral health-related inpatient admission or emergency room visit.

Discussion

Severe mental illnesses (SMIs) are often treated with antipsychotic medications, yet non-adherence to these medications is substantial and associated with increased healthcare use and costsCitation24 among a vulnerable population. The context of provider-patient interactions following an acute BH admission is an important setting to improve compliance with these medications, and ultimately, lower costs. This study employed a unique design including identification from a healthcare claims database, followed by abstraction of medical charts during outpatient care initiated after an acute BH-related event. Patterns of treatment with antipsychotic medication, documented provider discussions about compliance, and healthcare utilization and costs were compared based upon the presence or absence of a medication compliance discussion at the first observed visit after discharge.

During the first abstracted visit after the index event, 58% of patients had evidence of a discussion with the provider about antipsychotic medication compliance in the chart. The cohorts, defined by the presence of this initial compliance discussion, were largely similar in demographic and clinical characteristics. However, among patients having no such discussion at the first observed post-index visit, baseline diagnoses of schizophrenia were more common, as were conditions associated with schizophrenia and its treatment, than among patients who had a compliance discussion. This finding was counterintuitive, given the high published rates of non-adherence to antipsychotic medication among patients with schizophrenia.

One might expect an initial post-event visit would include a conversation about the importance of compliance with medication use. Patients who did not have evidence of a medication use-related compliance/adherence discussion at the first abstracted visit were significantly more likely to have a treatment change in the follow-up period. While treatment switching is not uncommon and may be necessary for SMI, it has been associated with earlier psychiatric relapse and increased HCRUCitation30. Until providers have greater access to reliable medication use (i.e. treatment adherence/compliance) data including individual reasons for non-complianceCitation20,Citation31, the impact of compliance-related discussions occurring after an acute event may not be fully understood. Nevertheless, evidence from this study suggests that early discussions about compliance are associated with a more consistent ongoing relationship between patient and provider and lower risk for a subsequent acute event.

Among those not having evidence of adherence/compliance discussions at the first visit, patients were less likely to be instructed to return to the provider for a future visit, and patients had fewer visits with the same provider, as compared with patients who did have a compliance discussion. In addition, patients not having first-visit compliance discussions had significantly fewer compliance discussions during all abstracted visits. Furthermore, compliance discussions about other forms of BH treatments (e.g. talk therapy) after the first visit were significantly fewer for patients who did not have initial medication compliance discussions. Our results reinforce studies that have demonstrated the importance of engaging patients in treatment decisionsCitation6–8.

While no statistically significant differences were observed in BH-related HCRU and costs generally, patients with ≥2 documented compliance discussions were at lower risk for subsequent costly BH acute events. However, BH-related HCRU and costs did not differ significantly in the baseline and follow-up periods based on the observation of a compliance discussion. Two factors may have contributed to these findings. First, the study selection criteria were intended to identify patients whose treatment history identified them as higher risk, increasing importance of stressing the compliance discussions. This same selection criterion, which is a strength for some study outcomes, may have inadvertently biased the sample by limiting the natural variability that would have been observed in a population with less restrictive inclusion criteria. Second, because healthcare costs are highly variable, the sample size may not have been sufficient to detect differences or results may have been skewed by patients with high costs, such as inpatient hospitalization costs.

Study limitations

Certain limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. All available BH visits in each medical chart were abstracted, and every effort was made to identify the provider most likely to provide continuing treatment for each patient. Nevertheless, the nature of service delivery may have necessitated that some patients receive treatment from more than one provider, including those whose first treatment after the index was not identified from the administrative claims data (as it may have been bundled into the acute event that defined the index date) or whose first visit after the index date was not with her or his “regular” provider because of scheduling challenges.

In addition, the data on compliance communication included in this analysis was only as good as the quality of the medical chart from which it was abstracted. The medical records included in this study represented a mix of hand-written progress notes as well as standard fields printed from electronic medical record applications. The results may have been skewed by the inclusion of standard electronic medical record text such as “take medications as directed,” which may not represent oral communication of treatment adherence/compliance. Furthermore, it is possible that adherence/compliance-related discussions took place but were not recorded in a manner detectable by the methods used to identify them in charts. Nevertheless, failure to include these data may have alternatively biased the results and not accurately represented the “real-world” treatment experience. This balance illustrates the challenges facing not only scientific investigators, but also patients, clinicians, and other stakeholders as the importance of matching patients with the most efficacious treatment is an ever-increasing component of service delivery.

The study included a small convenience sample size; however, the 90 included patients contributed more than 600 BH-related visits that were included in the analysis. Therefore, the number of patients was small, but the data they provided was robust. Nevertheless, it is possible the small sample was not truly representative of all US patients. The number of independent variables included in the Cox proportional hazards models was limited by the small number of patients with an acute BH event during follow-up. Larger sample size may have supported a more comprehensive model.

Finally, this study included only commercially insured patients with an observed high rate of compliance with follow-up ambulatory care visits. These results likely represent one end of the treatment spectrum and may not be generalizable to patients with other coverage types or those who are uninsured, especially among patients with a schizophrenia diagnosis. The study would have been strengthened by the inclusion of specific measures of adherence. Nevertheless, the low proportion of observed adherence/compliance-related discussions occurring amidst medication changes remains concerning in this sample of patients obtaining follow-up care, and represents an opportunity to enhance clinical practice for all patients.

Conclusion

Finding the ideal treatment regimen for patients with SMI requires a dialogue between the patient and provider that includes adherence and compliance to recommended therapies. Our findings suggest that patients with documented treatment adherence/compliance-related discussions may experience fewer changes to subsequent treatment, better follow-up with their provider, and lower risk for acute BH events in the future. Increasing the frequency of medication use-related treatment adherence/compliance discussions may represent an opportunity to improve the quality of care for these vulnerable patients and reduce the overall economic burden associated with the treatment of SMI diagnosis.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

At the time the study was conducted, authors FF and HW were employees of Otsuka, and authors CM, EK, JW, and AB were employees of Optum. Authors declare no other conflicts of interest. A peer reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed having received manuscript or speaker’s fees from Astellas, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Elsevier Japan, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Yakuhin, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Shire, Tsumura, Wiley Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and research grants from Eisai, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma and Shionogi. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Breanna Essoi of Optum and the Clinical Research Team at CIOX Health for their work in obtaining chart abstraction data. Medical writing services were provided by Yvette Edmonds and Caroline Jennermann, employees of Optum, as contracted by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization.

Data availability statement

Our database contains elements proprietary to Optum that cannot be disclosed publicly. Disclosure of data assumes data security and privacy protocols and a standard license agreement that possesses restrictive covenants about use of data.

References

- Mokdad AH, Ballestros K, Echko M, et al. The state of US health, 1990-2016: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US states. JAMA. 2018;319(14):1444–1472.

- World Economic Forum. The global economic burden of non-communicable diseases. 2011. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-economic-burden-non-communicable-diseases. Accessed 15 November 2018.

- Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(2):155–162.

- Cloutier M, Aigbogun MS, Guerin A, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2013. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(6):764–771.

- Cloutier M, Greene M, Guerin A, et al. The economic burden of bipolar I disorder in the United States in 2015. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:45–51.

- Dixon LB, Holoshitz Y, Nossel I. Treatment engagement of individuals experiencing mental illness: review and update. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(1):13–20.

- Easter A, Pollock M, Pope LG, et al. Perspectives of treatment providers and clients with serious mental illness regarding effective therapeutic relationships. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2016;43(3):341–353.

- Thompson L, McCabe R. The effect of clinician-patient alliance and communication on treatment adherence in mental health care: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:87.

- Semahegn A, Torpey K, Manu A, et al. Psychotropic medication non-adherence and its associated factors among patients with major psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):17.

- Desai R, Nayak R. Effects of medication nonadherence and comorbidity on health resource utilization in schizophrenia. JMCP. 2019;25(1):37–44.

- Forma F, Green T, Kim S, et al. Antispychotic medication adherence and healthcare services utilization in two cohorts of patients with serious mental illness. CEOR. 2020;12:123–132.

- Chapman SC, Horne R. Medication nonadherence and psychiatry. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(5):446–452.

- Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, et al. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:449–468.

- Mago R. Adverse effects of psychotropic medications: a call to action. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(3):361–373.

- Marcus SC, Olfson M. Outpatient antipsychotic treatment and inpatient costs of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(1):173–180.

- Novick D, Haro JM, Suarez D, et al. Predictors and clinical consequences of non-adherence with antipsychotic medication in the outpatient treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;176(2–3):109–113.

- Hong J, Reed C, Novick D, et al. Clinical and economic consequences of medication non-adherence in the treatment of patients with a manic/mixed episode of bipolar disorder: results from the European mania in bipolar longitudinal evaluation of medication (EMBLEM) study. Psychiatry Res. 2011;190(1):110–114.

- Offord S, Lin J, Mirski D, et al. Impact of early nonadherence to oral antipsychotics on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with schizophrenia. Adv Therapy. 2013;30(3):286–297.

- Offord S, Lin J, Wong B, et al. Impact of oral antipsychotic medication adherence on healthcare resource utilization among schizophrenia patients with Medicare coverage. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49(6):625–629.

- Shafrin J, Bognar K, Everson K, et al. Does knowledge of patient non-compliance change prescribing behavior in the real world? A claims-based analysis of patients with serious mental illness. CEOR. 2018;10:573–585.

- Shafrin J, May SG, Shrestha A, et al. Access to credible information on schizophrenia patients’ medication adherence by prescribers can change their treatment strategies: evidence from an online survey of providers. PPA. 2017;11:1071–1081.

- Shafrin J, Schwartz TT, Lakdawalla DN, et al. Estimating the value of new technologies that provide more accurate drug adherence information to providers for their patients with schizophrenia. JMCP. 2016;22(11):1285–1291.

- Predmore ZS, Mattke S, Horvitz-Lennon M. Improving antipsychotic adherence among patients with schizophrenia: savings for states. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(4):343–345.

- Jiang Y, Ni W. Estimating the impact of adherence to and persistence with atypical antipsychotic therapy on health care costs and risk of hospitalization. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35(9):813–822.

- Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–682.

- Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM/ICD-10/CM. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD [cited Accessed 2020 May 12]. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp; https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs10/ccs10.jsp.

- US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index. Medical Care. Series ID: SUUR0000SAM. 2017 [cited Accessed 2020 May 12]. Available at: http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost?su.2018.

- Weiss AJ, Barrett ML, Heslin KC, et al. Trends in Emergency Department Visits Involving Mental and Substance Use Disorders, 2006–2013. HCUP Statistical Brief #216. December 2016. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb216-Mental-Substance-Use-Disorder-ED-Visit-Trends.pdf

- Heslin KC, Weiss AJ. Hospital Readmissions Involving Psychiatric Disorders, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #189. May 2015. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb189-Hospital-Readmissions-Psychiatric-Disorders-2012.pdf

- Ayyagari R, Thomason D, Mu F, et al. Association of antipsychotic treatment switching in patients with schizophrenia, biopolar, and major depressive disorders. J Med Econ. 2019;26:1–9.

- Shafrin J, Forma F, Scherer E, et al. The cost of adherence mismeasurement in serious mental illness: a claims-based analysis. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(5):e156–e163.

Appendix

Table A1. Diagnosis codes used to identify schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, and major depressive disorder.