Abstract

Objectives

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare and severe, inflammatory skin disease. GPP is characterized by recurrent flares that consist of disseminated erythematous skin rash with sterile neutrophil-filled pustules that can result in an emergency department (ED) visit or hospital stay due to systemic complications. This study characterizes hospitalizations, ED visits, and inpatient treatment due to GPP in the United States (US).

Methods

A descriptive, retrospective cross-sectional analysis was conducted in Cerner Health Facts, a US electronic medical record database. Hospitalizations and ED visits were identified between 1 October 2015 and 1 July 2017. Visits were included in the study if they were GPP-related, defined as a GPP diagnosis (ICD-10-CM code: L40.1) in the first or second position at admission or discharge, and if the discharge date was within the study period. Hospitalizations and ED visits were the units of analysis. Demographics, comorbidities, medication use, and outcomes were characterized with descriptive statistics. Outcomes included length of stay, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and death.

Results

A total of 71 GPP-related hospitalizations and 64 GPP-related ED visits were included in the study. Other specified inflammatory skin conditions (OSICS)/skin and subcutaneous tissue infections (54%/34%), fluid and electrolyte disorders (46%), hypertension (30%), septicemia (24%), and acute renal failure (18%) were the most frequently coded conditions accompanying a GPP-related hospitalization. OSICS/skin and subcutaneous tissue infections (47%/42%) were the most commonly coded conditions accompanying a GPP-related ED visit. Medication use during GPP-related hospitalizations included topicals (triamcinolone (42%); clobetasol (17%)), systemic corticosteroids (prednisone (20%); methylprednisolone (11%)), and non-biologic and biologic immunosuppressants (cyclosporine (6%); methotrexate (4%); etanercept (1%)). Analgesics (acetaminophen 67%; morphine 24%), and antibiotics (vancomycin 21%) were also common. The median length of stay for hospitalizations was 5 days. Three hospitalizations included an ICU admission and two hospitalizations resulted in death.

Conclusions

The presence of concurrent immune-mediated conditions, and frequent prescribing of analgesics, including opioids, illustrate the burden of GPP in patients requiring acute and inpatient care.

Introduction

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare and severe inflammatory skin condition that can result in significant morbidity and mortality, and can co-occur with other inflammatory conditionsCitation1,Citation2. GPP is characterized by rapidly progressing diffuse dark erythematous patches with pustules that may coalesce to form lakes of pus distributed across the bodyCitation3. The skin is often painful and tender causing patient quality of life to be severely impaired during the course of a GPP flareCitation4,Citation5. Little is known about the prevalence or the incidence of GPP and published estimates range from 0.2 and 0.7 per 100,000 persons from separate studies in France and Japan, respectivelyCitation2,Citation6. GPP occurs most frequently between ages 40 and 60 yearsCitation7, and literature suggests that it is more prevalent among womenCitation8.

The clinical course of GPP is characterized by periods of disease quiescence and acute flares over the course of months and even yearsCitation4. Patients with flares experience systemic symptoms such as high fever, chills, malaise, diarrhea, arthralgia, and severe painCitation1,Citation2,Citation5. Flares are believed to be the main driver of healthcare resource use in GPP patients due to the risk of hospitalization, as they can lead to serious complications such as sepsis, renal failure, respiratory abnormalities, and even death in the inpatient settingCitation5,Citation9.

Existing treatments to manage signs and symptoms of GPP include topical and systemic therapy, and phototherapyCitation1,Citation10,Citation11. Although, there are currently no approved treatments for GPP in the United States (US), patients are treated similarly to plaque psoriasis patients and may receive cyclosporine or a biologic such as infliximab to stabilize their conditionCitation10,Citation11. Other therapies include adalimumab, etanercept, and combination of a systemic agent such as acitretin, cyclosporine, methotrexate, or apremilast and a biologicCitation10–12. In addition to these treatment options, there is limited evidence to support the use of newer biologics for treatment of GPP, including interleukin 17 (IL-17) and IL-23 targeted monoclonal antibodies, though their efficacy and safety have not been studied in randomized controlled trials involving GPP patientsCitation1,Citation10,Citation13,Citation14. Treatment response can vary due to the persistence of lesions, recurrence of flares, and the limited availability of clinical data about plaque psoriasis products highlighting unmet treatment need for GPP patientsCitation4,Citation15.

Despite the known severity of GPP and unmet treatment need, evidence is lacking about the frequency, duration and treatment of flares, and what proportion result in hospitalization. In a recent survey of dermatologists in North America, the majority of respondents (69%) reported their GPP patients averaged 0 to 1 flare annually, followed by one-third of respondents who reported an average of 2 to 3 flares annuallyCitation16. Dermatologists cited that steroid withdrawal (64%), infection (58%) and stress (50%) were the most common triggers for GPP flaresCitation16. GPP flares requiring hospitalization were reported as “very common/always required” by 21% of treating dermatologists with the most common durations for hospitalization ranging from 3 to 8 daysCitation16. Recent studies conducted in US administrative claims databases have found that GPP patients have increased healthcare utilizationCitation17 with higher rates of hospitalizations compared to the general populationCitation18. There is a need to characterize GPP patients who seek treatment in the hospital setting and better understand inpatient care for GPP in the US. This study describes hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits, and inpatient treatment for GPP in the US.

Methods

Data source

The US Cerner Health Facts (Cerner Corp., Kansas City, MO) database was used for this study. Cerner Health FactsFootnotei electronic medical record (EMR) data are derived from over 600 Cerner implementations throughout the United States. It contains clinical information for over 50 million unique patients with more than 10 years of records. Data in Health Facts are extracted directly from the EMRs of hospitals with which Cerner has a data use agreement. EMRs may include pharmacy, clinical, microbiology, laboratory, admission, and billing information from affiliated patient care locations. All admissions, medication prescribing and dispensing, laboratory orders, and specimens are date and time stamped, diagnoses and procedures are mapped to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, medication information includes national drug codes (NDCs), and laboratory tests are linked to their Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC).

Data available from 1 October 2015 to 1 July 2017 were used. The beginning of the study period, 1 October 2015, was selected to coincide with the implementation of the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) coding system in the US. The ICD-10 coding system includes a specific code for GPP (L40.1), while a specific code for GPP was not available in the ICD-9 coding system.

Study design and sample selection

A retrospective cross-sectional design was used for this descriptive study. The Cerner Health Facts EMR database was used to identify eligible hospitalizations and ED visits due to GPP between 1 October 2015 and 1 July 2017. Hospitalizations and ED visits were determined to be due to GPP (GPP-related) if a GPP diagnosis (ICD-10 code: L40.1) was documented as the primary or first secondary diagnosis during the encounter, suggesting that GPP was the reason for the visit (i.e. the diagnosis code was listed in the first or second position of the EMR at admission, discharge, or both). GPP-related visits were excluded if the discharge date was not available to ensure complete capture of services rendered during the hospitalization or ED visit.

Characterization of encounters

Demographics of the patients experiencing the GPP-related hospitalization or ED visit, including age at admission, sex, race (Caucasian, African American, Asian, Native American, Hispanic, Other), and US Census region (Midwest, Northeast, South, West) were reported.

Additional diagnoses coded during GPP-related hospitalizations and ED visits were also analyzed to understand comorbidities that were relevant to the hospital care. Diagnoses in the Cerner Health Facts EMR database were categorized using the clinical categories from the Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR) for ICD-10-CM formatCitation19. Skin-related disease classifications were further reported by their exact ICD-10 codes to understand relevant dermatologic diagnoses that accompanied a GPP diagnosis during the hospitalization or ED visit.

Study outcomes

The following outcomes were reported GPP-related hospitalizations: length of stay, death, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and medications prescribed. Length of stay was defined as the number of days between admission and discharge dates of the hospitalization. ICU admission was based on whether the patient’s location in the hospital or any service rendered during the visit took place in the ICU. Medication use was divided into two categories: (1) dermatologic and immunosuppressive, and (2) other frequently used medications by drug class. For each drug class, up to three of the most frequent medications prescribed were reported.

Statistical analyses

GPP-related hospitalizations and ED visits were the units of analysis. Descriptive statistics were reported to characterize patient demographics and comorbidities, as well as outcomes associated with each visit. Mean and standard deviations were reported to describe continuous variables; frequency and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Median and interquartile ranges were reported for continuous variables that were not normally distributed.

Results

Patient population and demographics

Out of a total of 2,461,749 hospitalizations and 8,285,559 ED visits identified during the study period, 71 hospitalizations and 64 ED visits met the eligibility criteria (). Of the 135 GPP-related visits, four patients had a second hospitalization and two patients had a second ED visit. The remaining patients had only one hospitalization or ED visit during the study period.

Table 1. Characteristics of all encounters meeting eligibility criteria.

GPP-related hospitalizations and ED visits were predominantly among Caucasian patients (68%; 59%), with a mean age of 51[standard deviation (SD): 22.6] and 41[SD: 15.5] years, respectively (). Males and females were evenly distributed among both visit types (males: 48%; females: 52%) ().

Primary diagnoses

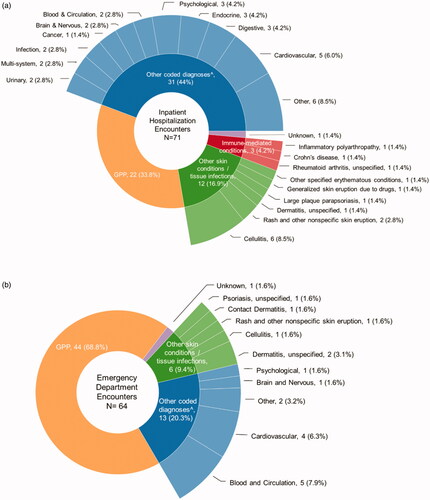

ED visits were more often coded with GPP as the primary diagnosis. GPP was the primary diagnosis in 34% of hospitalizations and 69% of ED visits (, ). Among the remaining visits where GPP was the first secondary diagnosis, 21% of hospitalizations and 25% of ED visits had a primary diagnosis of another skin condition including cellulitis, rash, dermatitis, or parapsoriasis (). Diabetes, hypertension, and septicemia were included among other coded primary diagnoses among hospitalizations (), while circulatory signs/symptoms and nonspecific chest pain made up the majority of other coded primary diagnoses among ED visits ().

Figure 1. (a) Primary diagnoses for GPP-related hospitalizations. (b) Primary diagnoses for GPP-related ED visits. ^Other coded diagnoses = Abnormal sputum; Acute kidney failure, unspecified; Acute on chronic systolic (congestive) heart failure; Acute post hemorrhagic anemia; Anal abscess; Anemia in other chronic diseases classified elsewhere; Calculus of ureter; Circulatory signs/symptoms; Diabetes; End-stage renal disease; Epilepsy, unspecified, not intractable, without status epilepticus; Fracture of unspecified part of neck of right femur, initial encounter for closed fracture; Hepatomegaly, not elsewhere classified; Hypertension; Hypocalcemia; Ileus, unspecified; Inflammatory polyarthropathy; Malignant neoplasm of unspecified part of unspecified bronchus or lung; Nonspecific chest pain, Other cirrhosis of liver; Other fatigue; Other pulmonary embolism without acute cor pulmonale; Other specified erythematous conditions; Pneumonia, unspecified organism; Respiratory failure, unspecified, unspecified whether with hypoxia or hypercapnia; Rheumatoid arthritis, unspecified; Septicemia, Tachycardia, unspecified; Unspecified atrial fibrillation; Unspecified dementia without behavioral disturbance

Comorbidities and skin-related conditions

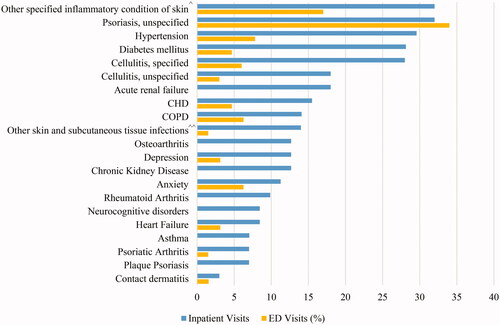

Other skin-related conditions documented during GPP-related hospitalizations included psoriasis, unspecified (32%), cellulitis (specified (28%) and unspecified (18%)), plaque psoriasis (7%), psoriatic arthritis (7%), and contact dermatitis (3%) (). Hypertension (30%), diabetes (28%), coronary heart disease (15%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (14%), chronic kidney disease (13%), and osteoarthritis (13%) were also frequently coded comorbidities among hospitalizations (). Depression and anxiety were documented in 13% and 11% of GPP hospitalizations, respectively (). Common comorbidities coded during ED visits for GPP included psoriasis, unspecified (34%), cellulitis (specified (6%) and unspecified (3%)), psoriatic arthritis (2%), and contact dermatitis (2%) ().

Figure 2. Proportion of GPP hospital encounters with coded comorbidities and other skin-related conditions. Abbreviations. CHD, Coronary heart disease; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ^Other specified inflammatory condition of skin includes: Other psoriasis; Seborrheic dermatitis, unspecified; Pruritus, unspecified; Erythema intertrigo; Bullous pemphigoid; Other specified erythematous conditions; Erythematous condition, unspecified; Sunburn of second degree; Other rosacea; Rosacea, unspecified; Hidradenitis suppurativa. ^^Other skin and subcutaneous tissue infections includes: Impetigo, unspecified; Pyoderma; Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome; Cutaneous abscess of neck; Cutaneous abscess of left lower limb; Cutaneous abscess of right foot; Cutaneous abscess, unspecified; Local infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, unspecified

Hospital outcomes

The average length of stay for GPP-related hospitalizations was 8.6 [SD: 14.0] days and the median length of stay was 5 [interquartile range: 3–9] days (). Three hospitalizations included an ICU admission and two separate hospitalizations resulted in death (). The average length of stay for the two hospitalizations that resulted in death was longer than the overall length of stay for GPP-related hospitalizations (14.5 days versus 8.6 days, respectively) ().

Table 2. Outcomes in GPP-related hospitalizations.

Medication use

Treatment during GPP-related hospitalizations included topicals, systemic corticosteroids, and immunosuppressants. Topicals included triamcinolone (42%) and clobetasol (17%), systemic corticosteroids included prednisone (20%) and methylprednisolone (11%), immunosuppressants included cyclosporine (6%) and methotrexate (4%) (). Etanercept was the only biologic reported and was used during one hospitalization (). Intravenous (IV) fluids (79%), analgesics (acetaminophen 67%; morphine 24%), and antibiotics (vancomycin 21%) were also common ().

Table 3. Top medications used for dermatologic treatment and immunosuppressive therapy.

Table 4. Other frequent medication usage during GPP hospitalizations.

Discussion

This study is the first to characterize GPP-related hospitalizations, ED visits, and inpatient treatment patterns in the US. GPP-related hospitalizations were associated with comorbidities and concurrent diagnoses of psoriasis, cellulitis, and other unspecified inflammatory skin conditions/infections which may add to the complexity of treating GPP patients. Other skin-related conditions and infections were found to be the primary diagnoses for some GPP-related hospitalizations and ED visits. These trends in admission and discharge coding may suggest uncertainty in diagnosing GPP due to its rarity, or may reflect the selection of more common conditions with approved therapies as the chief reason for the admission to justify treatment choice and reimbursement. It is important, however, that treating physicians can appropriately distinguish GPP from other dermatologic conditions as GPP may involve significant morbidity and potentially life-threatening complications such as sepsis, organ failure, or heart failure, requiring specific management strategies to optimize outcomesCitation12. Appropriate treatment could potentially reduce the length of hospital stay in GPP patients or avoid hospitalizations all together.

Three GPP-related hospitalizations led to ICU admission which suggests that some GPP patients require a higher level of care to manage complications associated with the visit. While there may be variability across hospitals in criteria for admission to the ICU, this finding in combination with the observation that two additional hospitalizations resulted in death, further demonstrates the potential seriousness of GPP when acute management is required.

Treatment during GPP-related hospitalizations commonly involved medications such as topicals and systemic corticosteroids, while in some cases other immunosuppressants were administered. The use of topical steroids and immunosuppressants was consistent with National Psoriasis Foundation recommendations to treat GPP, however, use of systemic corticosteroids as observed in this study, are not recommendedCitation11. Evidence suggests that the use and acute withdrawal of systemic corticosteroids to treat GPP can lead to an acute inflammatory process acting as a trigger for subsequent GPP flaresCitation1,Citation10,Citation11.

The prescribing of biologics for GPP was expected to be higher due to the assumption that the most severe cases of GPP require hospitalization and more intense therapy. We hypothesize that the low use of biologics may be due to a range of factors: there may have been an initial misdiagnosis of GPP upon admission or some patients may have already been on a biologic for a coexisting immune-mediated condition, or for GPP. Patients already treated with biologics, whether for GPP or for a coexisting immune-mediated condition – many of which were observed in this study, may not be eligible for additional doses or initiation of another biologic while in the ED or hospital. If a patient received a dose of their biologic near the admission date, they may need to wait weeks before receiving an additional dose depending on the timing of previous doses. In some cases, attending physicians in the inpatient setting may be reluctant to administer a biologic due to lack of experience treating GPP. Additional evidence would be necessary to test whether any of these hypotheses are plausible.

The pustulation, generalized erythema and desquamation seen in GPP are similar to the trauma observed in skin burnsCitation20. Among medications prescribed, frequent use of IV fluids and antiemetics was expected and known to be used for empiric treatment in the inpatient setting to stabilize patientsCitation21,Citation22. In patients with GPP, the use of these agents may reflect efforts to treat GPP flare systemic symptoms and complications such as dehydration or nauseaCitation1. These complications were reflected among the primary conditions recorded on the EMRs of hospitalizations where a GPP diagnosis was coded secondary. Frequent use of analgesics, including opioids during many GPP admissions were documented and suggest the need for significant pain management due to flaresCitation11. There was also common use of antibiotics which may have been due to the empiric treatment of suspected infection or may represent the frequency of infections occurring secondary to the breakdown of skin as a result of GPP.

There are limitations to this study. This was a cross-sectional study of hospitalizations and ED visits, and complete longitudinal patient-level data were not available from other encounters, such as those in other outpatient/office settings, making it challenging to adequately describe care prior to or after the encounter. Therefore, treatment patterns prior to the admissions were not known in this GPP patient population and may have affected inpatient treatment selection. This also may limit the completeness of comorbidities observed and the ability for this study to report on the outpatient medications that patients were treated with. Identification of comorbidities as well as the hospitalizations and ED visits included in this study relied on diagnosis codes which may misclassify encounters where an incorrect or nonspecific diagnosis was documented. One relevant example is impetigo herpetiformis, a rare pustular form of psoriasis, especially occurring in pregnancy with features of generalized pustular psoriasis. The Cerner EMR database used for this study also did not include free text physician notes. Without such notes to provide a detailed description of the care involved during hospitalizations or ED visits, it is not possible to confirm whether GPP patients were experiencing a flare at the time of the encounter. However, given the need for emergency care and inpatient admission in these patients and the documentation of a GPP diagnosis in the first or second position in the EMR, it is likely that they were seeking care for their flares. While the severity of GPP or the GPP flare could have affected treatment selection and the decision to admit a patient to the hospital instead of a discharge from the ED, severity could not be ascertained with these data. Another limitation is the generalizability of the study results. The study data set was derived from a sample of hospitals that use Cerner EMR systems. Thus, hospitals that subscribe to other EMR systems are not represented in the study data set and findings may not be representative of care during GPP encounters in those settings of care.

Conclusion

This study provides the first description of hospitalizations and ED visits for the treatment of GPP in the US. The presence of concurrent immune-mediated conditions, and frequent prescribing of analgesics, including opioids, illustrate the burden of GPP in patients requiring acute care. Future research using a longitudinal data set can provide much needed information about the course of GPP flares and how they are treated in inpatient and outpatient settings over a period of follow up.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This paper was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MLH, DS, SB, and WCV are or were employees of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. when the study was conducted. JJW is or has been an investigator, consultant, or speaker for AbbVie, Almirall; Amgen; Arcutis; Aristea Therapeutics; Boehringer Ingelheim; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Dermavant; Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories; Eli Lilly; Galderma; Janssen; LEO Pharma; Mindera; Novartis; Regeneron; Sanofi Genzyme; Solius; Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.; UCB; Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC; and Zerigo Health.

Author contribution

Study design and concept: DS, SB; Data analyses: DS, SB; Interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript: MLH, DS, SB, JW; All authors have read and approved the final draft of the manuscript submitted.

Previous presentations

Part of the results were presented in abstracts or posters at the 2020 European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology annual congress and the 2020 Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Nexus conference.

Acknowledgements

None

Notes

i Cerner HealthFacts (North Kansas City, MO) is a real-world, de-identified, HIPAA-compliant electronic health records database.

References

- Benjegerdes KE, Hyde K, Kivelevitch D, et al. Pustular psoriasis: pathophysiology and current treatment perspectives. Psoriasis. 2016;6:131–144.

- Augey F, Renaudier P, Nicolas JP. Generalized pustular psoriasis (Zumbusch): a French epidemiological survey. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16(6):669–673.

- Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983–994.

- Kharawala WH, Golembesky AK, Bohn RL, et al. The clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of generalized pustular psoriasis: a structured review. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16(3):239–252.

- Choon SE, Lai NM, Mohammad NA, et al. Clinical profile, morbidity, and outcome of adult-onset generalized pustular psoriasis: analysis of 102 cases seen in a tertiary hospital in Johor, Malaysia. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(6):676–684. Epub 2013 Aug 22.

- Ohkawara A, Yasuda H, Kobayashi H, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis in Japan: two distinct groups formed by differences in symptoms and genetic background. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996;76:68–71.

- Kalb RE. Pustular psoriasis: Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. UptoDate.com. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pustular-psoriasis-pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis. Jan 2019.

- Twelves S, Mostafa A, Dand N, et al. Clinical and genetic differences between pustular psoriasis subtypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(3):1021–1026.

- Borges-Costa J, Silva R, Goncalves L, et al. Clinical and laboratory features in acute generalized pustular psoriasis: a retrospective study of 34 patients. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12(4):271–276.

- Kearns DG, Chat VS, Zang PD, et al. Review of treatments for generalized pustular psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;15:1–3.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(2):279–288.

- Jeon C, Nakamura M, Sekhon S, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis treated with apremilast in a patient with multiple medical comorbidities. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3(6):495–497.

- Imafuku S, Honma M, Okubo Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: a 52-week analysis from phase III open-label multicenter Japanese study. J Dermatol. 2016;43(9):1011–1017.

- Wang W-M, Jin H-Z. Biologics in the treatment of pustular psoriasis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2020;19(8):969–980.

- Johnston A, Xing X, Wolterink L, et al. IL-1 and IL-36 are dominant cytokines in generalized pustular psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(1):109–120.

- Strober B, Kotowsky N, Medeiros R, et al. Unmet medical needs in the treatment and management of generalized pustular psoriasis flares: evidence from a survey of Corrona Registry Dermatologists. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(2):529–541.

- Kotowsky N, Gao R, Singer D, et al. PRO29 Healthcare Resource Utilization (HCRU) in patients with Generalized Pustular Psoriasis (GPP): a claims database study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2020:29(S3):5114.

- Hanna ML, Singer D, Valdecantos WC. Economic burden of Generalized Pustular Psoriasis and Palmoplantar Pustulosis in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(5):735–742.

- CCSR. Clinical Classifications Software Refined. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). November 2020. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccsr/ccs_refined.jsp.

- Varman K, Namias N, Schulman C, et al. Acute generalized pustular psoriasis, von Zumbusch type, treated in the burn unit. A review of clinical features and new therapeutics. Burns. 2014;40(4):e35–e39.

- Griddine A, Bush JS. Ondansetron. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020; [cited 2021 Jan]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499839/

- Malbrain M, Van Regenmortel N, Saugel B, et al. Principles of fluid management and stewardship in septic shock: it is time to consider the four D’s and the four phases of fluid therapy. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):66.