Abstract

Objective

The ObserVational survey of the Epidemiology, tReatment, and Care Of MigrainE study in Japan (OVERCOME [Japan]) aimed to provide an up-to-date assessment of migraine epidemiology in Japan.

Methods

OVERCOME (Japan) was a cross-sectional, population-based web survey of Japanese adults recruited from consumer panels. People with active migraine (met modified International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition [ICHD-3] criteria or had a self-reported physician diagnosis of migraine) answered questions about headache features, physician consultation patterns, and migraine medication use. The burden and impact of migraine were assessed using Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment scales.

Results

In total, 231,747 respondents accessed the screener, provided consent, and were eligible for the survey. The migraine group included 17,071 respondents (mean ± SD age 40.7 ± 13.0 years; 66.5% female). ICHD-3 migraine criteria were met by 14,033 (82.2%) respondents; 9667 (56.6%) self-reported a physician diagnosis of migraine. The mean number of monthly headache days was 4.5 ± 5.7 and pain severity (0–10 scale) was 5.1 ± 2.2. In the migraine group, 20.7% experienced moderate to severe migraine-related disability (MIDAS score ≥ 11). Work productivity loss was 36.2% of work time missed, including 34.3% presenteeism. Only 57.4% of respondents had ever sought medical care for migraine/severe headache. Most respondents (75.2%) were currently using over-the-counter medications for migraine; 36.7% were using prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and only 14.8% were using triptans. Very few (9.2%) used preventive medications.

Conclusions

Unmet needs for migraine health care among people with migraine in Japan include low rates of seeking care and suboptimal treatment.

Introduction

Migraine is a chronic neurological disease associated with substantial functional and quality-of-life impactsCitation1,Citation2. In 2019, migraine was second among the world’s leading causes of years lived with disability, and first among women aged 15–49 yearsCitation3. In Japan, migraine affects 6.0–8.4% of the populationCitation4,Citation5. The functional, quality-of-life, and economic impacts of migraine in Japan are beginning to be recognizedCitation6.

To date, only two population-based studies of migraine have provided evidence of prevalence rates, impact on individuals, and healthcare options for Japanese people with migraineCitation4,Citation5. Both studies revealed a high proportion of people who experienced a substantial impact of migraine on their daily activities; despite this, many people with migraine had not sought medical care for their headachesCitation4,Citation5. However, each of these studies had fewer than 6000 respondents and took place in 1997Citation4 and 1999Citation5, prior to the approval of triptans for migraine treatment in Japan (in 2000Citation7). More recently, the Adelphi Migraine Disease Specific Programme (data collected in 2014) showed that among adult migraine patients, lack of efficacy of their current therapy was a common concernCitation8. However, the Adelphi study was small (fewer than 1000 respondents), and data were collected from physicians and their adult patients with migraine, rather than being a population-based study. In another recent analysis, data from the 2017 Japanese National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS) indicated that people with migraine had poorer quality of life and greater work productivity impairments than matched controls, but again, the study sample size was small (just 378 migraine patients, with ≥4 headache days per month)Citation9. Thus, there is a lack of up-to-date knowledge of migraine prevalence, medical care and treatment, and the impact of migraine in the Japanese population. A comprehensive survey of a large representative sample of the Japanese population is needed to fill knowledge gaps and identify barriers to better healthcare outcomes for Japanese people with migraine.

The objectives of the ObserVational survey of the Epidemiology, tReatment, and Care Of MigrainE study in Japan (OVERCOME [Japan]) were to assess symptomatology, healthcare professional (HCP) consultation patterns, diagnosis, treatment, and impact of migraine in a representative sample of Japanese people. OVERCOME (Japan) is a cross-sectional observational study similar to the OVERCOME (US) studyCitation10, an ongoing longitudinal survey of migraine in a large representative sample of people in the United States. Here we summarize the study design and report on the broad-scale epidemiological data from OVERCOME (Japan).

Materials and methods

Study design

OVERCOME (Japan) was a cross-sectional, population-based web survey of adults with and without a migraine in Japan. Patients were enrolled in the study from July to September 2020. The study was approved by the Research Institute of Healthcare Data Science Ethical Review Board (ID: RI2020003), and all respondents provided informed consent.

The study comprised three stages. In Stage I, individuals from consumer panels were screened to construct a sample demographically matched to Japanese census data. In Stage II, eligible respondents from Stage I received a Migraine Diagnostic Module to identify those with migraine. The Migraine Diagnostic Module used modified criteria for migraine based on International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) criteriaCitation11, as validated in the American Migraine Study (AMS) and the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) StudyCitation12. People with migraine had active headaches in the past 12 months, and either screened positive for migraine on the Migraine Diagnostic Module or had a self-reported physician diagnosis of migraine. During this stage, quota sampling was used to identify a control group of individuals without active migraine in the past 12 months and no self-reported diagnosis of migraine or migraine symptomatology; this group was demographically matched to Japanese census data. In Stage III, a Migraine Assessment Survey was administered to people with migraine. The Migraine Assessment Survey characterized their headaches and assessed patterns of medical consultation, diagnosis, treatment patterns, and impact/burden of migraine. The control group identified during Stage II was administered a separate survey that focused on patterns of medical consultation and their perceptions of people with migraine.

Study population and selection criteria

Stage I: demographic screening survey

Stage I identified a respondent sample representative of the Japanese population using preset demographic sample size quotas for sex, age, and geographic region. Age and sex quotas were based on data for Japan retrieved from the US Census Bureau International Data BaseCitation13 on 12 December 2019. Geographic region quotas were set using regional population distribution data from the Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications of JapanCitation14, accessed in April 2019. As the quota targets were achieved, the random sample selection process was refined to target only panelists matching those demographic characteristics whose quotas had not yet been reached.

Participants for the study were members of a Kantar Profiles (Lightspeed) global panel and its panel partners. These are online survey double opt-in panels that use multiple methods to recruit panelists. Panelists receive a nominal number of points for completing a survey, and points accumulated over time can be redeemed for online gift certificates. An online screener was included in the web-based survey, which screened participants according to these inclusion criteria: aged 18 years or older, residence in Japan, member of online survey panel, access to the internet, ability to read and write Japanese, and ability to provide electronic informed consent. This resulted in 231,747 respondents who were eligible to progress to Stage II ().

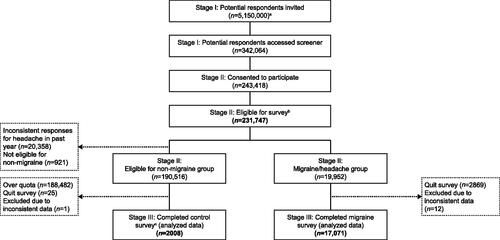

Figure 1. Patient flow chart. aTargeted sampling to represent the Japanese adult population in terms of key demographic characteristics (age, sex, and geography) were applied. bThe diagnostic stage involved those who passed the screener stage and represented the Japanese census adult population. cA quota of 2000 was set for the non-migraine group, thus the majority of respondents who were eligible for the non-migraine group were over quota. Note. Eligible respondents who quit the survey or had inconsistent data were not included in the final analyses.

Stage II: migraine diagnostic module

Stage II identified people with active migraine. People with migraine reported at least one headache in the past 12 months not associated with an illness, a head injury, or a hangover, and either screened positive for migraine on the Migraine Diagnostic Module (based on modified ICHD-3 criteria) or self-reported a physician diagnosis of migraine. A sample of 19,952 respondents met the above criteria () and was invited to complete the Migraine Assessment Survey (Stage III). Of those who were eligible for the non-migraine group, 2008 respondents completed the control survey ().

Stage III: Migraine Assessment Survey

Stage III assessed migraine symptoms, impact/burden, and healthcare patterns in the migraine group.

Measurements

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics

Respondent-reported demographic data in the current manuscript (collected in Stage I) include age, sex, geographic region of current residence, marital status, and employment status.

Clinical features of migraine and patient-reported outcomes

Migraine-related assessments from the Migraine Assessment Survey (Stage III) reported in the current manuscript include clinical features (age at migraine diagnosis [only for those who reported being diagnosed], number of monthly headache days), migraine attack features (presence/absence of visual symptoms associated with headache [“aura”], the timing of migraine attacks), and duration of most recent migraine/severe headache.

The impact of migraine, including average headache pain severity, was assessed using the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) scaleCitation15,Citation16. The MIDAS quantifies headache-related disability over a 3-month period and consists of five items that reflect days an individual missed or experienced reduced productivity at work, home, or social events. Higher MIDAS scores indicate more days with disability. Four categorical grades are often reported based on the total MIDAS score: Grade I: 0–5 = Little or No Disability; Grade II: 6–10 = Mild Disability; Grade III: 11–20 = Moderate Disability; and Grade IV: ≥21 = Severe DisabilityCitation15,Citation16. The MIDAS has demonstrated reliability and validity, and MIDAS scores are correlated with physicians’ assessments regarding the need for medical careCitation15,Citation16; the Japanese language version has been validatedCitation17. The average headache pain severity is patient-reported using an 11-point numerical rating scale, from 0 (no pain at all) to 10 (pain as bad as it could be).

Impacts on work productivity were assessed using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment for Migraine (WPAI-M) QuestionnaireCitation18. The questionnaire measures impacts on work productivity and regular activities over the past 7 days attributable to a specific health problemCitation18. The WPAI-M scale contains six items that measure employment status, hours missed from work due to the health problem, hours missed from work for other reasons, hours actually worked, the degree to which health affected work productivity, and the degree to which health affected productivity in regular unpaid activities. Four scores are calculated from the responses: absenteeism, presenteeism, work productivity loss, and activity impairment. Scores are calculated as impairment percentages, with higher numbers indicating greater impairment and less productivity, that is, worse outcomesCitation18.

Healthcare professional consultation

The Migraine Assessment Survey also measured HCP consultation patterns for migraine or severe headaches. Firstly, lifetime consultation with an HCP by specialty type was indicated by marking “yes” to every HCP type that applied. Secondly, respondents reported the number of HCP visits (by HCP type) for migraine/severe headache in the past 12 months and the number of HCP visits by specialty for any reason in the past 12 months. HCP types listed in the survey (terminology not formally validated) were internist/primary care, general neurologist (not a headache specialist), neurosurgeon, headache specialist, pain specialist, obstetrician-gynecologist, emergency room (emergency room at a hospital or urgent care center), occupational health physician located in the workplace, pharmacist at a pharmacy, or other types of doctor/specialist.

Medication use

The Migraine Assessment Survey included questions on lifetime and current use of medications specifically for migraine. Current use was defined as “currently using or typically keep on hand” for acute medications and “taken or used in the last 3 months” for preventives. Medications for acute treatment of migraine (including prescription and over-the-counter [OTC]) listed in the survey included specific names (brand/generic) of triptans, ergotamine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and simple/combination analgesics. Among the acute medications, lifetime use was only asked for OTC medications and triptans. Preventive medications for migraine listed in the survey included specific names (brand/generic) of antidepressants, antiseizure medications, and antihypertensive medications. Of note, non-medication strategies, such as medical devices, were not included since any medical devices were not regulatory approved for migraine treatment in Japan.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed on the migraine group data to provide an assessment of the epidemiology and burden of migraine. Specific attention was paid to clinical features of migraine, healthcare delivery, and medication use. Means and standard deviations (SDs) were reported for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Comparisons of measures between the non-migraine (control) and migraine groups were conducted using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Missing data were noted and reported as their own category; however, missing data were minimized by requiring a response to most survey questions and including response options such as “don’t know” and “prefer not to answer.” No imputation strategy was employed. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics

A total of 5,150,000 potential respondents were invited to participate in OVERCOME (Japan) (). Of these, 243,418 accessed the survey screener and consented to participate. The 231,747 respondents eligible for the diagnostic stage were a demographically representative sample of Japanese adults (Supplemental Table 1). Among eligible respondents completing the Migraine Diagnostic Module, 19,952 met the criteria for migraine (8.6% of those eligible). After removing eligible respondents who quit the survey (2869 respondents) or had inconsistent data (12 respondents), the final analyses were conducted on a migraine group size of 17,071 respondents.

The mean (SD) age of the migraine group was 40.7 (13.0) years, and approximately two-thirds (66.5%) were female (). The most common lifetime comorbidities in the migraine group were allergies/hay fever (49.4% of respondents), depression (15.4%), asthma (15.3%), and acid reflux/gastroesophageal reflux disease (14.5%; Supplemental Figure 1). Additional comorbidities reported by both the migraine and non-migraine groups are shown in Supplemental Figure 1.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of survey respondents.

Diagnosis, clinical features of migraine, and patient-reported outcomes

In total, 14,033 respondents (82.2% of the migraine group) met the ICHD-3 criteria for migraine, and 9667 (56.6%) self-reported a diagnosis of migraine (). Among those diagnosed, the mean (SD) and median (interquartile range) ages at diagnosis were 26.4 years (11.7) and 25 years (18–33 years), respectively. Interestingly, 7404 (43.4%) respondents met the ICHD-3 criteria but had not been diagnosed (). Diagnosed headache/migraine subtypes included tension-type headache (18.0%), stress headache (15.3%), and menstrual headache/migraine (10.6% of female respondents). On average, the migraine group had experienced 4.5 monthly headache days in the 90 days before the survey; 5573 respondents (32.6%) experienced 4 or more headache days per month (). Aura, defined as the presence of visual symptoms associated with headache, was experienced at least once by 7318 respondents (42.9%); 1116 people (6.5%) experienced aura during every or almost every migraine attack. More than half of respondents (9706; 56.9%) reported that their most recent headache lasted more than 4 h. Most respondents (42.8%) reported that their migraine attacks began between 12.00pm (noon) and 5.59pm.

Table 2. Diagnosis of migraine in survey respondents.

Table 3. Clinical features of migraine and patient-reported outcomes in the survey respondents.

The mean (SD) pain severity was 5.1 (2.2) on a 0–10 scale (). Moderate to severe migraine-related disability (defined by a MIDAS score of 11 or greater) was reported by 20.7% of respondents. The mean WPAI-M absenteeism score, representing the percentage of work time missed in the past 7 days, was 4.2% (). The mean presenteeism score, representing the percentage of work time impaired by migraine in the past 7 days, was 34.3%. Work productivity loss (total percentage of the missed time) was 36.2%, and the impairment in daily activities was 35.9%.

Healthcare professional consultation

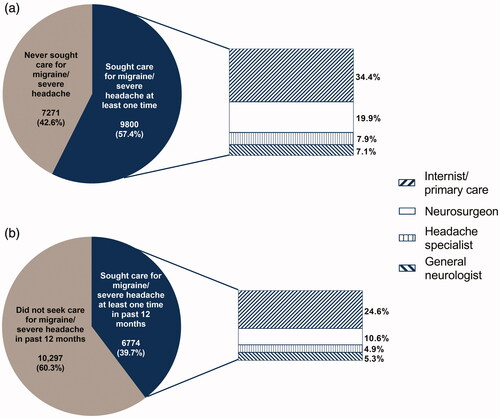

Only 57.4% of the people with migraine surveyed had ever sought medical care for migraine or severe headache (). The most common settings for lifetime consultation were internist/primary care (34.4%), neurosurgeons (19.9%), headache specialists (7.9%), and general neurologists (7.1%). Consultation at emergency or urgent care rooms was uncommon (2.6%). Lifetime consultation for migraine was also uncommon in a pharmacy setting (3.3%), with an obstetrician/gynecologist (3.0%), or with an occupational physician (1.8%). Within the past 12 months, an even smaller proportion (39.7%) of the migraine group had sought medical care for migraine/severe headache (). Again, the most common settings for HCP consultation were internist/primary care (24.6%), neurosurgeons (10.6%), headache specialists (4.9%), and general neurologists (5.3%). Similar proportions of people with and without migraine consulted HCPs for any reason in the past 12 months (control group data not shown). As expected, settings for HCP consultation differed between the two groups, with a larger proportion of the migraine group visiting neurosurgeons, headache specialists, and general neurologists (control group data not shown). Among the migraine group, the mean (SD) number of visits to an HCP in the past 12 months for any reason was 4.7 (9.8), with an average of 1.8 (5.8) visits for migraine or severe headache ().

Figure 2. HCP consultation patterns for the migraine group (N = 17,071). (a) Proportion of the migraine group who sought care for migraine/severe headache during their lifetime, and the four most common HCP types consulted. (b) Proportion of the migraine group who sought care for migraine/severe headache during the past 12 months, and the four most common HCP types consulted. Note. Pain specialist, emergency room, pharmacist, obstetrician/gynecologist, and occupational physician categories are not shown in this figure because of low consultation rates (≤3.3%) for lifetime care in the migraine group. Abbreviation. HCP, healthcare professional.

Table 4. Consultation and medication use in the migraine survey respondents.

Medication use

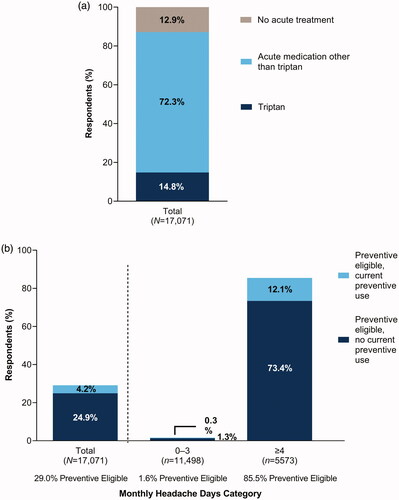

Most respondents (80.4%) had ever used an OTC acute medication, whereas 20.1% had ever used a triptan (). Approximately half (53.2%) of respondents currently used acute prescription medication, mostly NSAIDs (36.7%). Only 14.8% of respondents reported currently using triptans (; ).

Figure 3. Current medication use among Japanese people with migraine (N = 17,071). (a) Acute medications. (b) Preventive medication use among those eligible for preventive treatment. Preventive eligibility considered monthly headache days and MIDAS disability grade based on the American Headache Society consensus statementCitation22. Eligibility was defined three ways: ≥ 6 monthly headache days, 4–5 monthly headache days with at least some disability (MIDAS ≥ 6), or 3 monthly headache days with severe disability (MIDAS ≥ 21). “Current” defined as “currently using or typically keep on hand” for acute medications and “taken or used in the last 3 months” for preventive medications. Abbreviation. MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment.

Only 10.2% of respondents had ever used preventive treatment for migraine (). The current use of migraine preventive medication was even lower, at 9.2% (). Similar proportions of people with migraine were currently using antidepressants, antiseizure medications, or antihypertensives as a preventive treatment for migraine (∼5% of respondents each; ). Overall, 29% of respondents were eligible for preventive migraine treatment, but only 4.2% of eligible respondents were currently using preventives (). Among those with 4 or more headache days per month, 85.5% of respondents were preventive eligible, but only 12.1% were currently using preventives ().

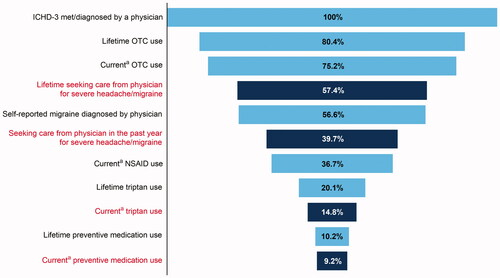

A visual summary of the current status of migraine diagnosis, HCP consultation, and medication use in Japan is provided in .

Figure 4. Current situation of migraine treatment in Japan (N = 17,071). a“Current” defined as “currently using or typically keep on hand” for acute medications and “taken or used in the last 3 months” for preventive medications. Abbreviations. ICHD-3, International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OTC, over-the-counter.

Discussion

OVERCOME (Japan) is the first nationwide, population-based, demographically representative survey to describe migraine diagnosis, physician consultation, and treatment patterns in Japan. Although the survey sample was demographically matched to the Japanese population, respondents with migraine were predominantly female and aged under 50 years. A substantial proportion of the individuals who met the diagnostic criteria for migraine had never consulted an HCP for migraine care or received a migraine diagnosis. In addition, many people with migraine were not receiving prescription acute or preventive medication. The results of the OVERCOME (Japan) survey will help clinical, scientific, and/or policy leaders to identify areas of unmet need and make informed decisions to address and improve migraine care in Japan.

The migraine prevalence and demographic profile of OVERCOME (Japan) support evidence from earlier population-based studies in Japan and elsewhere. Prevalence was estimated at 8.6% of respondents, similar to prevalence estimates from previous population-based studies in JapanCitation4,Citation5 but lower than the estimated global prevalence (14.4%Citation19). It is well known that more women than men live with migraine, and this was reflected in the survey results, with the migraine group being 66.5% female. This was a lower proportion of women than in previous population studies of migraine in Japan (79.2–81.6%Citation4,Citation5) but equivalent to the proportion of female patients with migraine in the 2017 Japan National Health and Wellness Survey (66.6%), which also used consumer survey panelsCitation20. The lower-than-expected proportion of women may in part be due to the slight male bias in the respondents eligible to participate in the OVERCOME (Japan) survey compared with the Japanese population as a whole (52 vs. 48%; Supplemental Table 1); possibly this is a limitation of the panel-based web survey design. With respect to the age of people with migraine in Japan, both in OVERCOME (Japan) and in a previous population studyCitation5, ∼50% of people with migraine were between the ages of 30 and 49 years. This is also consistent with the age profiles of migraine populations elsewhere in the worldCitation1,Citation21–23.

Clinical features of migraine in the OVERCOME (Japan) respondents were also consistent with previous population-based studies in Japan. However, respondents in OVERCOME (Japan) reported more frequent migraines than respondents in previous Japanese studies. The mean frequency for OVERCOME (Japan) respondents was 4.5 headache days per month, with 32.6% experiencing 4 or more headache days per month. In western Japan in 1999, most respondents reported the frequency of their headaches as “several times a year” (32–39%) or “1–2 times per month” (24–34%), although, among respondents who experienced aura, 32% experienced headaches one to two times per week or moreCitation5. The migraine frequency data from OVERCOME (Japan) indicate that many people with migraine in Japan may be candidates for preventive medications, recommended for those with frequent attacks that significantly interfere with daily routines despite acute treatmentCitation24. Among those who experienced ≥4 monthly headache days, 85.5% were eligible for preventive medication, but only 12.1% were currently using preventive medication; this highlights an unmet need for improved treatment options in this population. Undertreatment of eligible patients with preventive medication has also been noted in many other countries, including the US, Korea, and ItalyCitation23,Citation25,Citation26, and may in part be related to headache specialists who lack confidence in managing patients with treatment-resistant migraine (50.2% of respondents in a recent international surveyCitation27).

In the OVERCOME (Japan) study, 56.9% of respondents reported headache durations of 4 or more hours for their most recent headache, slightly more than the proportion experiencing headaches of this duration in 1999 (44–48%Citation5). OVERCOME (Japan) respondents also reported a mean pain severity of 5.1 (2.2) (scale maximum 10). These duration and severity data indicate that there may be an unmet need in Japanese people with migraine for more optimal acute treatment. Japanese clinical practice guidelines recommend stratified acute treatment of migraine according to headache severity and migraine-related disability: whereas NSAIDs are recommended for mild to moderate headache, triptans are recommended for moderate to severe headache and mild to moderate headache when NSAIDs have proven ineffectiveCitation28. As only 14.8% of OVERCOME (Japan) respondents were currently using triptans, despite long headache durations and moderate pain severity being common, there appears to be scope for improved stratified acute treatment of migraine in Japan.

Moderate to severe migraine-related disability (based on MIDAS scores) was experienced by 20.7% of OVERCOME (Japan) respondents. Although this is a relatively low disability rate for a migraine group, it is clear that many people with migraine in Japan experience a substantial disability burden. Moderate to severe migraine-related disability measured using MIDAS was reported by 36.0% of participants in a previous study of Malaysian banking sector employeesCitation29 and 49.8% of respondents in the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS)Citation30, which included participants from Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It is possible that lower rates of disability in the Japanese population may reflect Japanese cultural norms that expect presence at work and/or social events even when unwell. In the current study, the mean percentage of work time missed (absenteeism) was 4.2% compared with 14.4% in a European population with migraineCitation31. Culturally, we might expect presenteeism to have a greater impact in Japan than elsewhere, but the presenteeism score of 34.3% was in fact similar to that in the European population (35.2%Citation31) and slightly lower than in Malaysian banking sector employees (39.1%Citation29). However, in an analysis of data from the Japanese NHWS, the WPAI-M presenteeism score was 40.2% for people with ≥4 monthly migraine headache daysCitation9; this suggests that Japanese cultural norms fostering presenteeism may have a greater impact at higher headache frequencies. Lower MIDAS scores would be expected in a migraine group with few missed work or social events, even if they experience reduced productivity. This is consistent with the 1997 Japanese survey, in which respondents were asked to rate their daily impairment from “mild” (mild or no impairment) to “severe” (requiring bed rest always or frequently) and their disability in social activity from “mild” (slight or no impairment) to “severe” (canceling work or appointments always or frequently)Citation4. Using these scales, over 70% of respondents reported moderate or severe impairment of daily activity, but only 4.5% self-reported “severe” and 27.5% self-reported “moderate” disability in terms of reduced societal activityCitation4.

The OVERCOME (Japan) survey highlighted that a substantial proportion (42.6%) of Japanese people who meet the ICHD-3 criteria for migraine have never consulted an HCP for migraine/headache. This shows some improvement in patients seeking care since 1997 when 69.4% of survey respondents with migraine had never consulted an HCP for headacheCitation4, and in 1999 when 61.0% of those who had migraine with aura and 71.8% of those who had migraine without aura had never consulted an HCPCitation5. It is also concerning that 43% of those who met ICHD-3 criteria had never received a migraine diagnosis. Again, this is an improvement in previous studies. Only 11.6% of respondents who met diagnostic criteria for migraine in the 1997 survey were confident that they had been diagnosed with migraine by an HCPCitation4. It is clear that consultation and diagnosis rates in Japan could still be improved. Educating patients and physicians about migraine may be one way to improve consultation and diagnosis rates.

In the OVERCOME (Japan) survey, the most common settings for lifetime healthcare consultation for migraine/severe headache were internists/primary care (34%), neurosurgeons (20%), and neurologists (both headache specialists and general neurologists; 15%). In the IBMS, primary care doctors were consulted by up to 48%, and neurologists by up to 24%, of respondents, respectively; neurosurgeons were not consulted enough to be included in the reported resultsCitation30. The prevalence of Japanese patients consulting neurosurgeons reflects the unique structure of health care in Japan, where it is possible to access specialist HCP care without a referral from a primary care physician, and patients with headaches typically attend hospitals and/or neurosurgery clinics with computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging facilities for headache diagnosis and treatment. The easy access to specialist HCP care in Japan may also partially explain the relative rarity of seeking emergency care (<3% of respondents in OVERCOME [Japan]). In the IBMS, 5–8% of respondents reported seeking treatment at emergency departments in the 3 months before the surveyCitation2.

Both current and lifetime use of OTC medications was high (75 and 80% of the migraine group, respectively), there was moderate use of acute prescription medication, and both current and lifetime use of preventive medication was low (9 and 10%, respectively; ). Over 50% of the respondents in OVERCOME (Japan) were currently taking acute prescription medications, whether alone or in combination with OTC medication. However, only 14.8% of respondents were currently using migraine-specific acute medication (triptans). Triptans were first approved for acute treatment of migraine in Japan in 2000Citation7, so respondents in previous population-based studies did not have access to this acute treatment option. Comparing acute prescription medication use more generally, there has been some improvement since 1997 when only 24% of the surveyed respondents were taking prescription medication, whether alone or in combination with OTC medicationCitation4. However, as Sakai et al.Citation4 report only whether respondents were using OTC, prescription, or both types of medication, the types of acute prescription medications in use by these respondents are unknown but would not have included triptans.

The OVERCOME (Japan) study provides the first comprehensive epidemiological data on migraine in Japan for over 20 years. The strengths of the study include reducing selection bias by the inclusion of respondents who were not currently seeking migraine care from HCPs, and drawing from a demographically representative Japanese sample that included respondents with a large range of headache frequencies and migraine burden. The inclusion of patient-reported outcomes provided data that cannot be easily captured in other real-world evidence study methodologies (e.g. claims or electronic medical records data). In addition, validated measures were used wherever possible (e.g. AMS/AMPP diagnostic screener, MIDAS, and WPAI-M). Finally, the survey connected the respondents who sought medical care with their HCP settings, which gives a more complete picture of their use of the healthcare system.

There were also several important limitations to the OVERCOME (Japan) study. These were the reliance on self-reported data, the cross-sectional design, the low participation rate, and the sampling method. Because survey data were self-reported, they may be susceptible to recall bias. The cross-sectional nature of the data precludes the ability to make any causal inferences between any variables measured, for example, migraine symptomatology and health consultation patterns. There was the potential for participation bias because of both respondent self-selection and the low participation rate (∼7% of those invited). The participation rate may partially explain the lower-than-expected proportion of women with migraine and the overall lower-than-expected prevalence of migraine. Finally, although a quota sampling method was used to construct a sample that approximated the demographics of the Japanese population, there were differences in demography between the eligible survey respondents and the Japanese population. For example, women and individuals aged 65 years or over were underrepresented (see Supplemental Table 1; differences ∼5–10 percentage points). These patterns were likely related to general limitations of any online population survey (e.g. older adults are less likely to access and complete online surveys).

Conclusions

The results of the OVERCOME (Japan) survey show that despite significant impact on the population, many people with migraine in Japan have never consulted an HCP for migraine or severe headache and/or are not receiving potentially effective acute or preventive medication. These results highlight the considerable unmet need for migraine health care among people with migraine in Japan.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company and operated by Kantar Health. Eli Lilly and Company was involved in the study design, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. Kantar Health, the study operator, was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

KH received research funding from the Japanese Ministry for Health, Labour and Welfare and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development and has received personal fees from Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Eisai Co., Ltd., Pfizer Japan Inc., Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., MSD K.K., and Amgen Astellas BioPharma K.K. KU and MK are employees of Eli Lilly Japan K.K. and own minor shares in Eli Lilly and Company. AJZ, AMN, and YH are employees of, and own minor shares in, Eli Lilly and Company. At the time of the study, KJS was also an employee and minor shareholder of Eli Lilly and Company. DHJ is an employee of Kantar Health; Kantar Health received research funding for this study from Eli Lilly and Company. YM received personal consultancy fees from Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Amgen Astellas BioPharma K.K. during the conduct of the study. TT received personal fees from Eli Lilly Japan K.K., AbbVie GK, Amgen Astellas BioPharma K.K., Asahi Kasei Corporation, Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd., Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd., FUJIFILM Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd., Kowa Company, Ltd., Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Pfizer Japan Inc., Sawai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Lundbeck Japan K.K., Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co. Ltd., UCB Japan Co. Ltd, and Novartis Pharma K.K. during the conduct of the study, and personal fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited outside the submitted work. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in the interpretation of study results, and in the drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. KH, KU, MK, AJZ, KJS, AMN, DHJ, YM, and TT were involved in the study design. DHJ was an investigator in the study and was involved in data collection and statistical analysis. YH and AJZ also conducted the statistical analysis.

Hirata_et_al_OVERCOME__Japan__Supplemental_material.docx

Download MS Word (198 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Koa Webster, PhD, and Rebecca Lew, PhD, CMPP, of ProScribe – Envision Pharma Group, and was funded by Eli Lilly Japan K.K. ProScribe’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice (GPP3). The authors would like to thank all study participants. The authors sincerely thank Louise Lombard, formerly of Eli Lilly and Company, for her critical review of earlier versions of this manuscript.

References

- Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Kolodner K, et al. The family impact of migraine: population-based studies in the USA and UK. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(6):429–440.

- Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the Second International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS-II). Headache. 2013;53(4):644–655.

- Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, et al. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):137.

- Sakai F, Igarashi H. Prevalence of migraine in Japan: a nationwide survey. Cephalalgia. 1997;17(1):15–22.

- Takeshima T, Ishizaki K, Fukuhara Y, et al. Population‐based door‐to‐door survey of migraine in Japan: the Daisen study. Headache. 2004;44(1):8–19.

- Takeshima T, Wan Q, Zhang Y, et al. Prevalence, burden, and clinical management of migraine in China, Japan, and South Korea: a comprehensive review of the literature. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):111.

- Shimazawa R, Ando Y, Hidaka S, et al. Development of triptans in Japan: bridging strategy based on the ICH-E5 guideline. J Health Sci. 2006;52(4):443–449.

- Ueda K, Ye W, Lombard L, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and patient-reported outcomes in episodic and chronic migraine in Japan: analysis of data from the Adelphi Migraine Disease Specific Programme. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):68.

- Kikui S, Chen Y, Todaka H, et al. Burden of migraine among Japanese patients: a cross-sectional national health and wellness survey. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):110.

- Lipton RB, Araujo AB, Nicholson RA, et al. Patterns of diagnosis, consultation, and treatment of migraine in the US: results of the OVERCOME study. Headache. 2019;59(S1):2–3.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1–211.

- Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, et al. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41(7):646–657.

- US Census Bureau [Internet]. International Data Base (IDB): Japan 2020. Suitland (MD): US Census Bureau; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 12]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/idb/#/country?YR_ANIM=2019&FIPS_SINGLE=JA&COUNTRY_YEAR=2019&dashPages=BYAGE&ageGroup=1Y

- Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications of Japan [Internet]. National census: basic tabulation of population. Tokyo (Japan): Statistics Bureau; 2021 [cited 2021 May 7]. Available from: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?layout=datalist&cycle=0&toukei=00200521&tstat=000001080615&tclass1=000001089055&tclass2=000001089056&tclass3val=0&stat_infid=000031473211

- Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, et al. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology. 2001;56(6 Suppl 1):S20–S28.

- Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner K, et al. Reliability of the migraine disability assessment score in a population-based sample of headache sufferers. Cephalalgia. 1999;19(2):107–114.

- Iigaya M, Sakai F, Kolodner KB, et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire. Headache. 2003;43(4):343–352.

- Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–365.

- Stovner LJ, Nichols E, Steiner TJ, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):954–976.

- Igarashi H, Ueda K, Jung S, et al. Social burden of people with the migraine diagnosis in Japan: evidence from a population-based cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e038987.

- Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68(5):343–349.

- Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–1222.

- Kim BK, Chu MK, Yu SJ, et al. Burden of migraine and unmet needs from the patients’ perspective: a survey across 11 specialized headache clinics in Korea. J Headache Pain. 2021;22(1):45.

- American Headache Society. The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59(1):1–18.

- Silberstein S, Loder E, Diamond S, et al. Probable migraine in the United States: results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(3):220–229.

- Piccinni C, Cevoli S, Ronconi G, et al. A real-world study on unmet medical needs in triptan-treated migraine: prevalence, preventive therapies and triptan use modification from a large Italian population along two years. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):74.

- Sacco S, Lampl C, Maassen van den Brink A, et al. Burden and attitude to resistant and refractory migraine: a survey from the European Headache Federation with the endorsement of the European Migraine & Headache Alliance. J Headache Pain. 2021;22(1):39.

- Araki N, Takeshima T, Ando N, et al. Clinical practice guideline for chronic headache 2013. Neurol Clin Neurosci. 2019;7(5):231–259.

- Wong LP, Alias H, Bhoo-Pathy N, et al. Impact of migraine on workplace productivity and monetary loss: a study of employees in banking sector in Malaysia. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):68.

- Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia. 2011;31(3):301–315.

- Vo P, Fang J, Bilitou A, et al. Patients’ perspective on the burden of migraine in Europe: a cross-sectional analysis of survey data in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):82.