Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate the time use and both direct and indirect costs associated with subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) for adults with allergic rhinitis (AR) and caregivers of children with AR in the US.

Methods

We conducted a survey to assess the retrospective time use and direct costs of SCIT. The populations surveyed included adults and caregivers of children (aged 5–17) with symptomatic AR of moderate or higher severity who are currently receiving or have previously started allergy immunotherapy (AIT). The retrospectively collected, self-reported time consumption and direct costs per clinic visit when receiving SCIT were assessed as well as the productivity loss associated with SCIT. Data were analyzed using univariate descriptive statistics.

Results

The study included 106 adults with AR and 191 caregivers of children with AR. We found that the median time spent per visit to the clinic was 50 min for both groups, including travel time and time at the clinic. The direct costs related to each visit included parking fees, road tolls and other costs. Adults spent $10 on parking, $9 on tolls and $10 on other costs. Finally, a median of 4 h of work was missed for both the adult patients and the adults accompanying a child.

Conclusions

We found that SCIT is associated with substantial direct patient costs and productivity loss for both adults with AR and caregivers of children with AR.

Introduction

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is an immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated non-infectious inflammatory disease that affects the nasal mucous membranes. AR is often classified by the severity of the symptoms and is induced by seasonal allergens (e.g. pollen from timothy grass, ragweed, tree) or perennial allergens (e.g. house dust mite)Citation1.

In the US, an estimated 10%–20% of adults and close to 40% of children have ARCitation1,Citation2. Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey revealed that the US population is most commonly sensitive to house dust mites (27.5%), perennial rye (26.9%) and ragweed (26.2%)Citation3.

Comorbidities of AR include atopic dermatitis, allergic asthma and conjunctivitisCitation4,Citation5. Studies have shown that AR affects work productivity, concentration, sleep and quality of lifeCitation4,Citation6. A pooled analysis from a systematic review of 19 observational and 9 interventional studies revealed that 35.9% of patients experienced impairment of at-work performance due to ARCitation7.

AR can be managed pharmacologically with symptom-relieving medication (e.g. antihistamine and intranasal corticosteroids), by allergen avoidance, or with allergy immunotherapy (AIT)Citation1,Citation8. AIT can be administered as subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) or as sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) (drops or tablets)Citation9 and is indicated for people who have AR that is not controlled by symptomatic therapy and who have confirmed IgE-mediated diseaseCitation6,Citation10,Citation11. The long-term disease-modifying effect has been demonstrated after three to five years of AIT, due to the modification of the immunologic pathways causing the allergic responseCitation12–14.

Cox et al.Citation15 estimated that 2%–9% of people with AR in the US receive AIT. Increased use of SLIT has occurred during the last decade, due to FDA approving four SLIT-tablets. However, the vast majority of patients are still initiated on SCITCitation16,Citation17.

Both monoallergic and polyallergic patients can benefit from SCITCitation18, Polyallergic patients can be treated either with parallel single-AIT formulations or with mixed formulations that include two or more allergens. However, mixtures containing allergens that do not belong to the same homologous group must always be justifiedCitation19. In the US, mixed-formulation SCITCitation18 is the common approach for treating poly allergic patientsCitation16.

SCIT is administered in medical settings by a healthcare professional in two phases: a buildup phase and a maintenance phase. During the buildup phase, the injections contain progressively greater amounts of allergensCitation20,Citation21. The starting dose is 1000 to 10,000 times lower than the maintenance dose. The buildup phase normally consists of 12 weeks of twice-weekly injections or 28 weeks of once-weekly injections, for a total of 24 or 28 visits, respectively, to the clinic. An accelerated buildup—either cluster immunotherapy or rushed immunotherapy—can be used to reach the maintenance dose sooner. In cluster immunotherapy, the patient receives multiple shots per visit for four to eight weeks; in rushed immunotherapy, the patient receives incremental doses at intervals of 15–60 min over 1 to 3 d until the maintenance dose is reachedCitation10. A study conducted in the US and Canada found that the average buildup phase comprised injections once or twice a week for 25 weeks, which indicates that on average, patients have 25 to 50 clinic visits during the buildup phaseCitation22. In the maintenance phase, patients receive injections every second or fourth weekCitation10,Citation20,Citation21. The recommended duration of the entire SCIT treatment course is 3 to 5 yearsCitation1,Citation8. It is recommended that the patient is monitored in the first 30 min after the injections due to the risk of anaphylactic shockCitation1,Citation10.

Blume et al.Citation22 investigated the administration and burden of SCIT in the US and Canada. The study enrolled 376 patients from 6 sites in the US. The results revealed that patients in the US and Canada received an injection every 3 to 4 weeks during the maintenance phase for an average of 4 years, for a total of 45 to 61 visits during this phase, and that patients on average spent 80 min per visit for a SCIT injection. The patients waited on average from 5 to 10 min before the injection (depending on the site), and the time in the examination room ranged from 1 to 6.5 min. Patients then waited approximately 30 min after the injection for observation, as recommended, due to the risk of anaphylactic shockCitation1,Citation10. Patients spent about 17 to 25 min traveling to the clinic, each wayCitation22. SCIT treatment is hence time-consuming for patients. In fact, the burden of time and travel on patients has been reported as the most cited reason for discontinuing SCITCitation23. In addition to the time use, patients incur direct costs such as travel expenses and, in some cases, lost earnings resulting from the patient’s time off from work.

The aim of this study was to investigate the time use and direct costs associated with SCIT of adults with AR and caregivers of children with AR in the US. Whereas Blume et al.Citation22 focused on time use and costs associated with the waiting time before injection, the time spent in the exam room, the waiting time after the injection, and travel time, here we estimated the total patient cost associated with SCIT, including direct costs related to the clinic visit and costs related to lost productivity. These costs are important because patient costs are relevant inputs for decision-makers in charge of treatment guidelines, reimbursement or regulatory approval.

Methods

We conducted an electronic survey among adults and caregivers of children (aged 5–17 years) with symptomatic AR of moderate or higher severity, who are currently receiving or have previously started AIT. To ensure accurate recollection in this retrospective study, we restricted the population of respondents with previous AIT to only those who have stopped/completed the treatment in the past 5 years (2015 or later). Caregivers answered the survey on behalf of the children with AR.

The questionnaire included sociodemographic questions and allergy-specific questions to determine respondents’ (or children’s) specific allergies, symptoms, and medication use and frequency; to determine whether they had an asthma diagnosis; to assess their quality of life (using EQ-5D-5L and VAS), and to evaluate their AIT course.

The self-reported time consumption and direct costs per clinic visit when receiving SCIT were assessed, and the respondents were asked to think back to their last time receiving SCIT. The caregivers were first asked whether their child was accompanied to the clinic, and if so, whether the respondent, their partner or another adult accompanying the child. Both the adults and the caregivers were asked to specify the mode of transport they used to get to the clinic, the travel time (one way), the total time of the visit, how long they waited after the AIT, and what other transportation costs the visit entailed, such as parking or tolls or other costs (for example gasoline or wear and tear of the car).

The survey assessed respondents’ productivity loss by asking them whether they had missed work, either partly or completely, to obtain AIT. If the caregivers did not accompany their child to the clinic themselves, they were asked whether the adult who did accompany the child missed work to do so. Furthermore, the respondents were asked how many hours of work they missed receiving AIT. The caregivers were also asked whether their child received SCIT during school hours.

The survey was approved by IntegReview IRB, Texas, USA. Adults with AR and caregivers of children with AR were invited to answer the questionnaire through email panels in collaboration with Kantar/Gallup. Data collection was financed by ALK. Two of this article’s authors are employees at ALK.

Data were collected from July 22 to November 7, 2020.

Pilot study

A pilot study was carried out in July 2020 with 9 adults and 10 caregivers to test the accuracy and relevance of the survey. Because the survey was modified following the pilot phase, the respondents from the pilot were not included in the final analysis.

Exclusion and data validation

Survey responses were checked for errors and consistency before being included in the statistical analysis. Respondents who had received or were receiving SLIT and those finishing SCIT before 2015 were excluded.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using univariate descriptive statistics (means, medians, frequencies and standard deviation).

Means are reported for the results of the descriptive statistics. The time use and cost results are reported as medians, as these are less sensitive to outliers than are the means.

Results

Sample

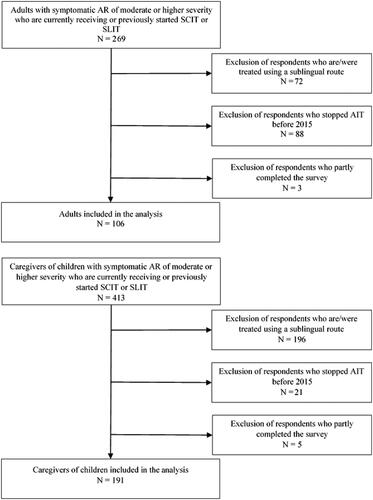

A total of 269 adults with AR and 413 caregivers of children with AR started the survey. Of those, 163 adults and 222 caregivers were excluded because they only partly completed the survey, they had stopped AIT before 2015, or had received AIT administered sublingually. Thus, 106 adults and 191 caregivers were included in the analysis. A flowchart of the inclusion of the study population is shown in . 84% of the adults and 82% of the children were currently receiving AIT, the remaining have previously received AIT and stopped after 2015. Of the 17 adults who have previously received AIT, 8 completed the treatment, 7 stopped before it was complete and 2 do not know why they stopped. Of the 34 children who have previously received AIT, 29 completed the treatment and 5 stopped before it was complete.

The respondents’ demographics and disease-specific characteristics are shown in and , respectively. The mean age of the adult respondents was 42 years; 68% were male, and the median EQ-5D score was 0.77. The mean age of the caregivers was 38 years, and 59% were male. The mean age of the children was 11 years, and 73% were male. The median household income category was $75,000 to $99,999 for both adults and caregivers. Of both the adults and children, 65% had an asthma diagnosis in addition to their allergy. The median EQ-5D scores for the adults with asthma and without asthma were 0.74 and 0.82, respectively. The majority of both the adults and the children used oral antihistamines, decongestants, nasal sprays and drops, and eye drops. Of the respondents using oral antihistamines, 68% of the adults and 59% of the children took the medication every day. More than three-quarters of both the adults and the children were polyallergic.

Table 1. Demographics.

Table 2. Disease-specific characteristics.

Time consumption and cost related to SCIT

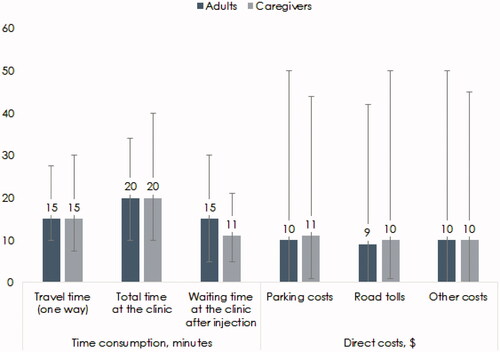

The median time consumption and the direct costs related to SCIT at a clinic are shown in . The children were accompanied by the caregiver answering the survey (92%), the caregiver’s partner (20%) or another adult (2%). The caregivers were asked to check all that applied.

Figure 2. The time consumption and direct costs associated with one visit at the clinic for subcutaneous immunotherapy, median, inter quantile range.

Table 3. Time consumption and costs related to SCIT.

Both adults and adults accompanying a child spent 15 min traveling (one way) (inter quantile range (iqr) 10–28 min). The total time spent at the clinic was 20 min for both adult patients (iqr 10–34 min) and adults accompanying a child (iqr 10–40 min). Of these 20 mins, the waiting time after injection was higher for the adults alone, at 15 min (iqr 5–30 min) than for adults accompanying a child, who spent only 11 min waiting (iqr 5–21 min). The waiting time after the injection reported in this study is lower than the recommended 30 min after receiving SCITCitation1. In total, the time spent per visit was 50 min for both groups, including both travel time and time at the clinic.

The direct costs related to each visit included parking fees, road tolls and other costs. Adults spent $10 (iqr $0–$50) on parking, $9 (iqr $0–$42) on tolls and $10 (iqr $0–$50) on other transportation-related costs (for example gasoline or wear and tear of the car). This resulted in a total (median) direct cost per visit of $29. The person accompanying the child to the clinic spent $11 (iqr $0–$44) on parking fees, $10 (iqr $0–$50) on road tolls and $10 (iqr $0–$45) on other transportation-related costs, for a total (median) of $31 per visit.

Two-thirds of the adults either completely or partly missed the workday to receive SCIT. Of those, the majority missed work completely for the treatment. The same was found for the adults accompanying children to the clinic. A median of 4 h of work was missed for both the adult patients and the adults accompanying a child. The majority of both the adult patients and the adults accompanying a child were transported to the clinic by car. In addition, most of the children missed school hours; 86% of the children received SCIT either fully or partly during school hours ().

Discussion

In this study, we found that patients receiving SCIT spent a total of 50 min per SCIT visit, including transportation time and time spent at the clinic. This is lower than the time found by Blume et al. Citation22, who reported that patients on average spent 80 min per SCIT visit. This difference was mainly caused by differences in the reported waiting time. Specifically, the respondents investigated by Blume et al.Citation22 waited 30 min after the injection before leaving the clinic, whereas the adults and children in this study reported themselves that they waited 15 min and 11 min, respectively. The recommended waiting time due to the risk of systemic reactions is 30 minCitation1,Citation10. The difference in self-reported actual waiting time could be explained by the fact that patients included in the study by Blume et al.Citation22 were observed as they waited after treatment, and so may have been more compliant. This could indicate that when patients are not observed, they are less adherent to treatment guidelines and leave sooner after receiving the injection. The difference between the self-reported waiting time and the recommended waiting time could also be the result of recall bias, as the respondents were asked to think of the last time they received treatment or an agreement between the patient and the clinic.

We found that the median respondent missed a total of 4 h of work per clinic visit. Multiplying that time by the number of treatments shows that the total productivity loss was about $7036 for a full SCIT course consisting of 91 visits, assuming a median hourly wage of $19.33Citation24. Similarly, we found that the total direct patient costs associated with a visit to the clinic were $29 for adults and $31 for caregivers of children with AR, resulting in a total direct cost of $2639 and $2821, respectively, for the full treatment course. Nearly half of the direct patient costs and productivity loss—49.9%—are incurred in the first year of SCIT because of the more frequent visits during the buildup phase.

If 15% of US adults between 18 and 65 years of age have AR, 6% of those with AR are receiving AIT, 93% of those treated with AIT are receiving SCIT, and assuming all of those patients complete the full 4-year treatment course, approximately 1,543,263 US adults of working age receive a full course of SCIT. This implies that these patients incur a total annual productivity loss of $1.85 billion as well as annual direct patient costs of $1.02 billion.

Similarly, these estimates give an annual productivity loss of $1.79 billion as well as additional annual direct patient costs of $1.05 billion for caregivers if everyone in the estimated population of 1,494,381 children receiving SCIT completed their full 4-year treatment course.

Moreover, although most patients do not complete a full treatment course with SCIT, the majority of the estimated productivity loss and direct patient costs will occur during the buildup phase due to the shorter time between the injections.

SLIT-tablets are an alternative to SCIT. SLIT-tablets can be administered by the patients themselves every day at home except for the first dose, which should be received at the clinic followed by an observation period of 30 minCitation1. SLIT-tablets therefore greatly reduces the number of visits to a clinic for administration of therapy, and thereby would reduce the productivity loss and patient costs compared with SCIT. However, some patients receiving SLIT tablets might need to travel to a pharmacy to receive their prescription. The frequency of the visits depends on the pack size and number of packages prescribed at a time.

We found that respondents with AR who had received AIT have a lower quality of life than what has previously been found among the general US population. Adult respondents indicated a utility of 0.77 as measured by EQ-5D-5L, which is 0.162 utility points lower than the score for the general population in the US between the ages of 35 and 44 yearsCitation25. The adult subpopulation of those with AR with asthma had an even lower utility, of 0.74. This emphasizes the importance of offering effective treatment to this population with AR. Additionally, it can explain patients’ willingness to invest a significant amount of time and money to relieve their allergies.

Limitations

The respondents in the study were asked to recall their last visit to the clinic, but as some of the respondents could have finished their treatment five years prior to the survey, it is possible that their recollections were not accurate.

The respondents were not asked whether they were on a standard, rush or cluster schedule or how many injections they had received until this point in time. Furthermore, the reasons for stopping treatment before finishing were not explored.

The gender distribution in this study differs from that of previously published studies. A large retrospective cohort study from Germany found that 48% of adults receiving SCIT were maleCitation26, and a real-world study in the US found that 43% of patients with any AIT claim were maleCitation27. We believe that the gender composition does not affect the results of this study, as the time and direct costs spent per clinic visit are not gender-specific.

Conclusion

We found that SCIT is associated with substantial direct patient costs and productivity loss for both adults with AR and caregivers of children with AR. We also suggest that SCIT may have a negative impact on educational attainment for children with AR.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by ALK, Hørsholm, Denmark.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

M Tankersley is a speaker and consultant for ALK. T Winders discloses that Allergy & Asthma Network and Global Allergy & Airways Patient Platform receive funding for unbranded disease awareness and education. M Aagren and Henrik Brandi Pedersen are employees at ALK, Denmark. M Bøgelund, MH Pedersen and AS Ledgaard Loftager are employees at Incentive Denmark, which is a paid vendor of ALK, Denmark. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Authors’ contributions

All authors have made a significant contribution to the work whether in conception and design; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting/revision of the manuscript; revising it critically for intellectual content or in all these areas. All authors have approved the final version to be published and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- Seidman MD, Gurgel RK, Lin SY, et al. Clinical practice guideline: allergic rhinitis executive summary. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(2):197–206.

- Meltzer EO, Blaiss MS, Derebery MJ, et al. Burden of allergic rhinitis: results from the pediatric allergies in America survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(3 Suppl):S43–S70.

- Arbes SJ Jr, Gergen PJ, Elliott L, et al. Prevalences of positive skin test responses to 10 common allergens in the US population: results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(2):377–383.

- Cingi C, Gevaert P, Mösges R, et al. Multi-morbidities of allergic rhinitis in adults: European academy of allergy and clinical immunology task force report. Clin Transl Allergy. 2017;7:17.

- Scadding GK, Kariyawasam HH, Scadding G, et al. BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of allergic and non-allergic rhinitis (revised edition 2017; first edition 2007). Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47(7):856–889.

- Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA(2)LEN and AllerGen). Allergy. 2008;63 Suppl 86:8–160.

- Vandenplas O, Vinnikov D, Blanc PD, et al. Impact of rhinitis on work productivity: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(4):1274–1286.e9.

- Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guideline: Non-infectious rhinitis – treatment for allergic rhinitis [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jan 25]. Available from: https://www.icsi.org/guideline/respiratory-illness/non-infectious-rhinitis-treatment-for-allergic-rhinitis/

- Tankersley M, Han JK, Nolte H. Clinical aspects of sublingual immunotherapy tablets and drops. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124(6):573–582.

- Cox L, Nelson H, Lockey R, et al. Allergen immunotherapy: a practice parameter third update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(1 Suppl):S1–S55.

- Canonica GW, Durham SR. Allergen Immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis and asthma: a Synopsis [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2020 Nov 13]. Available from: https://www.worldallergy.org/education-and-programs/education/allergic-disease-resource-center/professionals/allergen-immunotherapy-a-synopsis

- Jutel M, Akdis CA. Immunological mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotherapy. Allergy. 2011;66(6):725–732.

- Bachert C, Larché M, Bonini S, et al. Allergen immunotherapy on the way to product-based evaluation – a WAO statement. World Allergy Organ J. 2015;8(1):29.

- Sheikh J. Allergic rhinitis [Internet]. medscape.com. 2018. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/134825-guidelines

- Cox L, Calderon MA. Subcutaneous specific immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a review of treatment practices in the US and Europe. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(12):2723–2733.

- Cox L, Jacobsen L. Comparison of allergen immunotherapy practice patterns in the United States and Europe. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103(6):451–460.

- Sivam A, Tankersley M. Perception and practice of sublingual immunotherapy among practicing allergists in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122(6):623–629.e2.

- Passalacqua G. The use of single versus multiple antigens in specific allergen immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis: review of the evidence. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;14(1):20–24.

- Demoly P, Passalacqua G, Pfaar O, et al. Management of the polyallergic patient with allergy immunotherapy: a practice-based approach. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2016;12:2.

- AAAAI. American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2020 Nov 12]. Available from: https://www.aaaai.org

- Elliott J, Kelly SE, Johnston A, et al. Allergen immunotherapy for the treatment of allergic rhinitis and/or asthma: an umbrella review. CMAJ Open. 2017;5(2):E373–E385.

- Blume SW, Yeomans K, Allen-Ramey F, et al. Administration and burden of subcutaneous immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis in U.S. and Canadian clinical practice. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(11):982–990.

- Cox LS, Hankin C, Lockey R. Allergy immunotherapy adherence and delivery route: location does not matter. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(2):156–160.e2.

- Gould E. State of Working America Wages; 2019 [Internet]. [cited 2021 Feb 24]. Available from: https://www.epi.org/publication/swa-wages-2019/

- Jiang R, Janssen MFB, Pickard AS. US population norms for the EQ-5D-5L and comparison of norms from face-to-face and online samples. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(3):803–816. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Feb 23]. Available from: http://link.springer.com/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02650-y

- McDonell AL, Wahn U, Demuth D, et al. Allergy immunotherapy prescribing trends for grass pollen-induced allergic rhinitis in Germany: a retrospective cohort analysis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2015;11(1):19.

- Stone B, Rance K, Waddell D, et al. Real-world mapping of allergy immunotherapy in the United States: the argument for improving adherence. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2021;42(1):55–64.