Abstract

Objective

To perform a systematic literature review and indirect treatment comparison (ITC) to identify, summarize and quantify randomized controlled trial (RCT) evidence evaluating combination anticoagulant or P2Y12 inhibitor with low-dose aspirin versus low-dose aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events in patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and/or peripheral artery disease (PAD).

Methods

We performed an updated search of CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE through 23 August 2021 to identify RCTs of adult patients with chronic CAD and/or PAD that compared combination anticoagulant or P2Y12 inhibitor with low-dose aspirin to low-dose aspirin alone. Outcomes of interest included major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) including cardiovascular death, stroke, or myocardial infarction (MI) and bleeding. When needed, outcomes were pooled using random-effects models to generate hazard or risk ratios (HRs or RRs) and accompanying 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Adjusted ITCs using subsequent pooled HRs/RRs were then performed.

Results

Six publications reporting the results of two unique RCTs (one evaluating clopidogrel + aspirin vs. aspirin alone and the other rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily + aspirin vs. aspirin alone) were analyzed. The ITC suggested that rivaroxaban + aspirin was associated with a lower risk of MACEs compared with clopidogrel + aspirin (HR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.68–0.98). When looking at the individual components of MACE, rivaroxaban + aspirin was associated with lower risk of cardiovascular death (HR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.57–0.98) and stroke (RR = 0.67, 95 CI = 0.49–0.93) and similar risk of MI (RR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.70–1.23) versus clopidogrel + aspirin. No evidence of a difference in moderate-to-severe bleeding, fatal bleeding or intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) was seen between the two treatment strategies.

Conclusions

Compared to clopidogrel + low-dose aspirin, the use of rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily + low-dose aspirin reduced the risk of MACE, CV death and stroke including ischemic stroke in patients with or at high risk for chronic CAD and/or PAD. These benefits of rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily + low-dose aspirin compared to clopidogrel + low-dose aspirin appear to be achieved without significantly increasing patients’ risk of moderate-to-severe bleeding, including ICH or fatal bleeding.

Introduction

Despite the frequent use of aspirin to prevent major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) in stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and/or peripheral artery disease (PAD), patients’ risk for cardiovascular (CV) death, ischemic stroke or myocardial infarction (MI) remains considerableCitation1–7. Clinical guidelinesCitation8,Citation9 endorse the use of either rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) or a P2Y12 platelet inhibitor in combination with daily low-dose (75–100 mg) aspirin in patients who are at moderate-to-high risk of atherothrombotic events but not high risk for bleeding. The relative efficacy and safety of these competing strategies is unclear due a paucity of head-to-head randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparisons.

We performed a systematic literature review and indirect treatment comparison (ITC) to identify, summarize and quantify RCT evidence evaluating combination anticoagulant or P2Y12 inhibitor with low-dose aspirin versus low-dose aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events in patients with stable CAD and/or PAD.

Methods

This manuscript was written to conform to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statementCitation10.

Information sources and search strategy

Bauersachs et al.Citation11 previously performed a systematic review addressing a similar (though somewhat broader) key question with their literature search extending through February 2018. We updated the Cochrane CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE searches (Supplemental Table S1) of Bauersachs et al. from 1 March 2018 through 23 August 2021. The search was not limited by language.

Table 1. Study characteristics.

Our review included RCTs of adult patients with chronic CAD and/or PAD that compared combination anticoagulant or P2Y12 inhibitor with low-dose aspirin (75–162 mg/day) versus low-dose aspirin alone. Further, included studies had to report data for both MACEs (CV death, stroke or MI) and bleeding. After removing duplicates, two investigators (C.I.C., W.L.B.) screened titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible studies. We subsequently reviewed full-text publications if both reviewers agreed they were eligible. All studies included in the prior systematic review by Bauersachs et al.Citation11 were screened for inclusion. Backward citation tracking of all included papers was performed to find additional studies that might be eligible.

Data collection and risk of bias assessment

Two investigators (C.I.C., W.L.B.) extracted data from each included study using a common data collection tool with disagreements resolved by discussion. The following was collected: (1) first author and publication year; (2) study characteristics (i.e. study sample size, design, setting and duration); (3) baseline demographics (i.e. age, sex, comorbidities); (4) details of the interventions; and (5) outcome data. Risk of bias (RoB) was assessed using the Cochrane RoB Tool, Version 2Citation12. This tool assesses RoB in five domains: the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome and selection of the reported result. Responses to each result in judgements of “low”, “some”, or “high” RoB.

Outcomes

Our primary efficacy outcome was MACEs while the primary safety outcome was bleeding. We also assessed individual components of MACEs (CV death, stroke, MI) and all-cause death. Because we anticipated that bleeding outcome definitions might vary across trialsCitation13 and that these bleeding definitions may differ in the types and severity of bleeds includedCitation14, we analyzed bleeding in our ITC using each trial’s primary definition, by individual subtypes (fatal bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) and, when possible, by severity.

Synthesis methods

When available, data for each outcome reported as hazard ratios (HR) and accompanying 95% confidence intervals (CI) were pooled. When only raw event data was available, risk ratios (RRs) and accompanying 95% CIs were calculated and utilized. Traditional pairwise, random effects model pooling was planned when analyses included three or more RCTs. As this threshold was not met, no pooled analyses were conducted. Adjusted ITCs of pairwise effect estimates were then performed according to the methods described by Bucher et al.Citation15 using R version 4.0.3 (The R Project for Statistical Computing).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

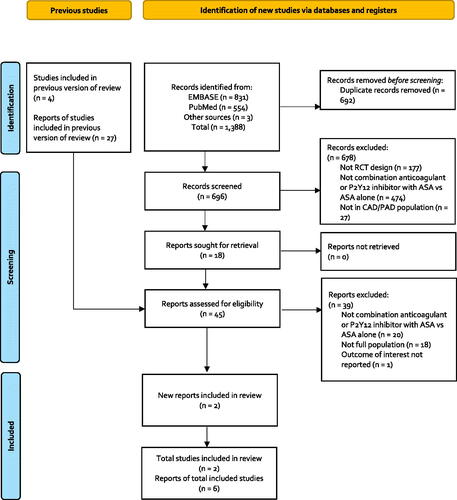

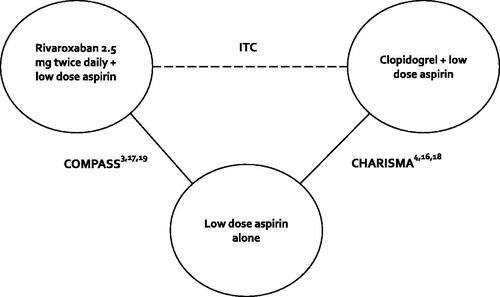

depicts the results of our literature search. Our updated search identified 1388 non-duplicate records, of which 18 required full-text review following title and abstract screening. After screening studies included in Bauersachs et al.Citation11, we include a total of six publicationsCitation3,Citation4,Citation16–19 reporting the results of two unique RCTsCitation3,Citation4. The two RCTs included in this analysis were the Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance (CHARISMA) trialCitation4 and the Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulation Strategies (COMPASS) trial ()Citation3.

Figure 1. Flowchart of included citations. Abbreviations. ASA, Acetylsalicylic acid; CAD, Coronary artery disease; PAD, Peripheral artery disease; RCT, Randomized controlled trial.

Figure 2. Diagram of the indirect treatment comparison. Abbreviations. CHARISMA, Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance; COMPASS, Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulation Strategies; ITC, Indirect treatment comparison.

The CHARISMA trialCitation4 enrolled 15,603 participants at high risk for a cardiovascular event if they were ≥45 years old with any of the following: multiple atherothrombotic risk factors, documented coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease or symptomatic PAD. Participants were then randomized to receive the combination of clopidogrel (75 mg/day) + aspirin (75–162 mg/day) versus placebo + aspirin (75–162 mg/day) for a median follow-up of 28 months. The COMPASS trial enrolled 27,395 participants with stable atherosclerotic vascular disease defined as established CAD, PAD or bothCitation3. Study participants <65 years old were also required to have documented atherosclerosis in ≥2 vascular beds or have ≥2 additional risk factors. Participants were randomized to receive rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice/day) + aspirin (100 mg/day), placebo + aspirin alone (100 mg/day) or placebo + rivaroxaban alone (5 mg twice/day) for a mean follow-up of 23 months. For the purposes of this analysis, only data from the rivaroxaban + aspirin and aspirin alone arms are included as the rivaroxaban 5 mg twice/day regimen has not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

shows some of the comparative characteristics of the included trials. The CHARISMA trial enrolled individuals either with or at risk for a cardiovascular event, with three quarters having established cardiovascular diseaseCitation4. This includes nearly half of individuals with documented coronary disease, nearly 23% with PAD, just over a third with a previous myocardial infarction (MI) and a quarter with a history of stroke. The COMPASS trial enrolled individuals with established stable CAD and/or PADCitation3. This includes over 90% with CAD, just over a quarter with PAD, over 60% with a previous MI and 4% with a history of stroke.

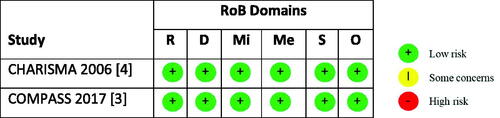

RoBs for the included RCTs are shown in . Both included trials were assessed to have a low RoB across each of the five domains.

Figure 3. RoB assessment. Abbreviations. R, Risk arising from the randomization process; D, Bias due to deviations from intended interventions; Mi, Bias due to missing outcome data; Me, Bias in measurement of the outcome; S, Bias in selection of the reported result; O, Overall risk of bias; CHARISMA, Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance; COMPASS, Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulation Strategies; RoB, Risk of bias.

Efficacy outcomes

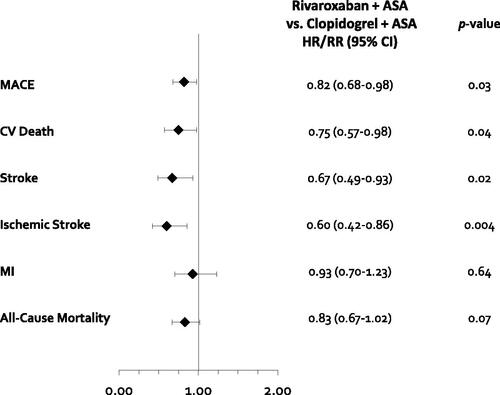

As only two RCTsCitation3,Citation4 met inclusion criteria, one evaluating clopidogrel + aspirin vs. aspirin aloneCitation4 and the other rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily + aspirin vs. aspirin aloneCitation3, no pairwise random effects model meta-analysis was needed. Pairwise comparison results for rivaroxaban + aspirin versus aspirinCitation3 and clopidogrel + aspirin versus aspirinCitation4 are shown in . Results of the ITC suggested that rivaroxaban + aspirin is associated with a lower risk of MACE (CV death, stroke or MI) compared with clopidogrel + aspirin (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.68–0.98) (). When looking at the individual components of the MACE composite, rivaroxaban + aspirin is associated with lower risk of CV death (HR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.57–0.98) and stroke (RR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.49–0.93) and similar risk of MI (RR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.70–1.23) versus clopidogrel + aspirin. No evidence of a difference in all-cause mortality (HR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.67–1.02) was seen, but rivaroxaban + aspirin was associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke versus clopidogrel + aspirin (RR = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.42–0.86).

Figure 4. Results of efficacy outcomes for the indirect treatment comparison. Abbreviations. CI, Confidence interval; CV, Cardiovascular; HR, Hazard ratio; ICH, Intracranial hemorrhage; MACE, Major adverse cardiovascular event; MI, Myocardial infarction; RR, Risk ratio.

Table 2. Results of efficacy outcomes for the indirect treatment comparison.

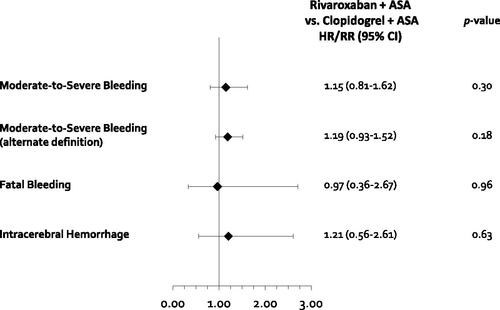

Safety outcomes

Results of the ITC suggested that there was no evidence of a difference in moderate-to-severe bleeding between rivaroxaban + aspirin (which used a modified International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis [ISTH] major bleeding definition)Citation3 and clopidogrel + aspirin (which used the Global Utilization of Strategies to Open Occluded Arteries [GUSTO] definition for moderate and severe bleeding) (HR = 1.15, 95% CI = 0.81–1.62)Citation4,Citation18 (, ). When an alternate definition of moderate-to-severe bleeding was analyzed (whereby additional data on severity by clinician assessment was used for the COMPASS trial effect sizeCitation17) a similar result was seen (RR = 1.19, 95% CI = 0.93–1.52). No evidence of a difference in fatal bleeding (HR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.36–2.67) or ICH was seen between the two treatment strategies (HR = 1.21, 95% CI = 0.56–2.61).

Figure 5. Results of safety outcomes for the indirect treatment comparison. Abbreviations. CI, Confidence interval; CV, Cardiovascular; HR, Hazard ratio; ICH, Intracranial hemorrhage; MACE, Major adverse cardiovascular event; MI, Myocardial infarction; RR, Risk ratio. *Calculated using moderate/severe bleeding per clinician evaluation collected from Eikelboom et al., Citation17.

Table 3. Results of safety outcomes for the indirect treatment comparison.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and ITC comparing the vascular dose of rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) along with a low-dose aspirin daily to clopidogrel + low-dose aspirin in patients with or at high risk for chronic CAD and/or PAD. It demonstrated that rivaroxaban + low-dose aspirin was associated with an 18% relative hazard reduction for MACEs versus clopidogrel + low-dose aspirin. This reduction in MACE risk was driven by a 25% reduction in the hazard of CV death and a 33% reduction in the risk of stroke (including a 40% reduction in ischemic stroke) with rivaroxaban + aspirin. While all-cause death had a HR of 0.83 (favoring rivaroxaban + aspirin) the 95% CIs crossed the line of unity (0.67–1.02). No difference in stable CAD and/or PAD patients’ risk of MI was observed. The benefits observed with rivaroxaban + aspirin versus clopidogrel + aspirin were achieved without significant increases in patients’ risk of moderate-to-severe, fatal or ICH bleeding.

The CHARISMA and COMPASS trialsCitation3,Citation4 underpinning this ITC utilized common but different definitions of bleeding. CHARISMA’sCitation4 primary bleeding outcome was severe GUSTO bleeding (ICH or bleeding resulting in substantial hemodynamic compromise requiring treatment), while COMPASS utilized a modified ISTH major bleeding definition (fatal or symptomatic critical organ bleeding, bleeding into a surgical site requiring reoperation, or bleeding requiring hospitalization)Citation3. Prior antithrombotic trial analyses have suggested the GUSTO severe and ISTH major bleeding definitions are not in close agreement regarding bleed severity, with only ∼25% of ISTH major bleeds categorized as GUSTO severeCitation11,Citation17. To address this issue, we utilized supplemental data from both RCTs, enabling us to compare a combined moderate-to-severe GUSTO bleeding outcome from CHARISMACitation18 to either an a priori modified ISTH bleedingCitation3 or an adjudicated, investigator severity-ranked moderate-to-severe bleeding definition for COMPASSCitation17. The similarity in “recalibrated” moderate-to-severe bleeding rates for the aspirin only (control) arms (2.5% for CHARISMA versus 1.9–2.3% for COMPASS) should reassure readers that “like” definitions of bleeding were used in this ITC. It should also reassure clinicians that our ITC’s findings of similar moderate-to-severe bleeding rates between rivaroxaban + aspirin and clopidogrel + aspirin (using either COMPASS definition) are less likely to be biased due to differing outcome definitions.

Our ITC was unable to assess the comparative efficacy of rivaroxaban + aspirin versus clopidogrel + aspirin on the key outcomes of need for lower limb revascularization or amputation due to a lack of reporting of such outcomes in CHARISMACitation4. The potential impact of these two strategies on major adverse limb events (MALEs) does however merit some discussion here. A subanalysis of PAD patients enrolled in the COMPASS trial (∼27% of all randomized) demonstrated that rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily + low-dose aspirin was associated with a 46% (95% CI = 18–65%) reduction in MALEs including the need for major amputationCitation20. The benefits of the vascular dose of rivaroxaban with aspirin in PAD patients is further supported by the results of the Vascular Outcomes Study of Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) Along with Rivaroxaban in Endovascular or Surgical Limb Revascularization for PAD (VOYAGER PAD) trialCitation21 which evaluated 6564 patients who had recently undergone lower-extremity revascularization. VOYAGER PADCitation21 demonstrated that rivaroxaban at a dose of 2.5 mg twice daily + aspirin was associated with a lower incidence of acute limb ischemia, major amputation for vascular causes, MI, ischemic stroke, or CV death compared to aspirin alone (HR = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.76–0.96), albeit at the cost of a small increase in ISTH major bleeding (5.94% vs. 4.06%; HR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.10–1.84). These data are in contrast to the Clopidogrel and Acetylsalicylic acid in bypass Surgery for PAD (CASPAR) trialCitation22 that failed to show that clopidogrel 75 mg/day + aspirin reduced the risk of the composite outcome of index-graft occlusion or revascularization, above-ankle amputation of the affected limb, or death compared to aspirin alone when administered to patients undergoing below-knee bypass grafting (HR = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.78–1.23).

Adjusted ITC is a commonly employed method that can be informative when head-to-head trial evidence is not availableCitation15,Citation23,Citation24. However, concerns with using this method to indirectly compare the efficacy and safety of combination anticoagulant or P2Y12 inhibitor with low-dose aspirin versus low-dose aspirin alone in stable CAD and/or PAD include potential bias due to cross-RCT differences in patient populations and duration of follow-up, sensitivity to modeling assumptions, and differences in outcome definitionsCitation15,Citation23,Citation24. In addition to the differences in bleeding outcomes discussed above, CHARISMACitation4 and COMPASSCitation3 also notably varied in the proportion of patients who had only vascular risk factors compared to established vascular disease, as well as the proportion of patients with a prior history of stroke. Guidance for interpreting ITCCitation23 suggests that some relative variation in the patient populations may be desirable for comparative effectiveness reviews such as ours, as they may more adequately reflect routine clinical practice. However, the results from this ITC should be interpreted in the light of these limitations; and would ideally be confirmed using another study design to reduce cross-trial differences such as a head-to-head RCT (less likely), individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis (requires access to IPD for both RCTs) or matching-adjusted indirect comparisons (MAICs) (IPD from one RCT can be combined with published aggregate data for the other)Citation23,Citation24.

Conclusions

Compared to clopidogrel + low-dose aspirin, the use of rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily with low-dose aspirin is associated with a lower risk of MACEs, CV death and stroke including ischemic stroke in patients with or at high risk for chronic CAD and/or PAD. These benefits of rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily + low-dose aspirin compared to clopidogrel + low-dose aspirin appear to be achieved without significantly increasing patients’ risk of moderate-to-severe bleeding including ICH or fatal bleeding.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC, Titusville, New Jersey.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

C.I.C. has disclosed that he has received research funding and honoraria from Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC, Bayer AG and Alexion Pharmaceuticals. A.A.K. and B.B. have disclosed that they are Janssen Pharmaceuticals employees. No potential conflict of interest was reported by W.L.B. CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors had a role in study design; data collection, analysis and interpretation of data; writing the report; and approved the manuscript for submission.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.9 KB)Acknowledgements

Ethical approval: This systematic review and indirect treatment comparison used aggregate data only and was deemed exempt for IRB oversight.

References

- Bhatt DL, Eagle KA, Ohman EM, et al. ; REACH registry investigators. Comparative determinants of 4-year cardiovascular event rates in stable outpatients at risk of or with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2010;304(12):1350–1357.

- Miao B, Hernandez AV, Alberts MJ, et al. Incidence and predictors of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with established atherosclerotic disease or multiple risk factors. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(2):e014402.

- Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Bosch J, et al. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in stable cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1319–1330.

- Bhatt DL, Fox KAA, Hacke W, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(16):1706–1717.

- Leeper NK, Ting W, Kharat A, et al. Incidence of major adverse cardiovascular and/or limb events among patients using aspirin for secondary prevention. Adv Card Res. 2020;3(2):266–274.

- Berger A, Simpson A, Bhagnani T, et al. Incidence and cost of major adverse cardiovascular events and major adverse limb events in patients with chronic coronary artery disease or peripheral artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2019;123(12):1893–1899.

- Berger A, Simpson A, Leeper NJ, et al. Real-world predictors of major adverse cardiovascular events and major adverse limb events among patients with chronic coronary artery disease and/or peripheral arterial disease. Adv Ther. 2020;37(1):240–252.

- Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, et al. ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(34):3227–3337.

- American Diabetes Association. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes – 2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(Suppl 1):S125–S150.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

- Bauersachs R, Wu O, Briere JB, et al. Antithrombotic treatments in patients with chronic coronary artery disease or peripheral artery disease: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Cardiovasc Ther. 2020; 2020:3057168.

- Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

- Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the bleeding academic research consortium. Circulation. 2011;123(23):2736–2747.

- Bergmark BA, Kamphuisen PW, Wiviott SD, et al. Comparison of events across bleeding scales in the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. Circulation. 2019;140(22):1792–1801.

- Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, et al. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(6):683–691.

- Berger PB, Bhatt DL, Fuster V, et al. Bleeding complications with dual antiplatelet therapy among patients with stable vascular disease or risk factors for vascular disease. Results from the clopidogrel for high atherothrombotic risk and ischemic stabilization, management, and avoidance (CHARISMA) trial. Circulation. 2010;121(23):2575–2583.

- Eikelboom JW, Bosch JJ, Connolly SJ, et al. Major bleeding in patients with coronary or peripheral artery disease treated with rivaroxaban plus aspirin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(12):1519–1528.

- Berger JS, Bhatt DL, Cannon CP, et al. The relative efficacy and safety of clopidogrel in women and men. A sex-specific collaborative meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(21):1935–1945.

- Eikelboom JW, Bhatt DL, Fox KAA, et al. Mortality benefit of rivaroxaban plus aspirin in patients with chronic coronary or peripheral artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(1):14–23.

- Anand SS, Bosch J, Eikelboom JW, et al. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in patients with stable peripheral or carotid artery disease: an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10117):219–229.

- Bonaca MP, Bauersachs RM, Anand SS, et al. Rivaroxaban in peripheral artery disease after revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1994–2004.

- Belch JJ, Dormandy J, CASPAR Writing Committee, et al. Results of the randomized, placebo-controlled clopidogrel and acetylsalicylic acid in bypass surgery for peripheral arterial disease (CASPAR) trial. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52(4):825–833, 833.e1-2.

- Jansen JP, Fleurence R, Devine B, et al. Interpreting indirect treatment comparisons and network meta-analysis for health-care decision making: report of the ISPOR task force on indirect treatment comparisons good research practices: part 1. Value Health. 2011;14(4):417–428.

- Signorovitch JE, Sikirica V, Erder MH, et al. Matching-adjusted indirect comparisons: a new tool for timely comparative effectiveness research. Value Health. 2012;15(6):940–947.