Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to gather multi-stakeholder insights on key issues relating to plain language summaries (PLS) of company-sponsored medical research to inform future industry recognized guidelines.

Methods

We identified diverse stakeholders based on expertise, familiarity with PLS, and geographical location. A Working Group (n = 11) with extensive expertise in PLS developed an initial list of 14 questions relating to PLS, which were shared with stakeholders. We used a modified Delphi approach to prioritize the 10 key questions that were then used to structure stakeholder discussions to collect evidence on the key challenges and opportunities to inform best practice for PLS.

Results

Overall, 29 stakeholders took part in the study, representing different professional sectors and geographies. There was strong alignment among stakeholders on the priority questions for PLS, with high response rates for both surveys (69% and 90%). Moderated online sessions were attended by 27/29 stakeholders and opportunities to improve PLS uptake were highlighted: developing industry-wide PLS guidelines would help define and maintain quality, including having a clear directive for when publications should have a PLS; further advocacy is needed by target audiences to ensure PLS become an established part of company-sponsored research publications; a searchable repository could facilitate discoverability and broad dissemination of PLS to multiple target audiences.

Conclusions

Key issues identified by stakeholders provide broad insights into the real and perceived barriers relating to PLS uptake. Each emerging theme presents a possible action that could accelerate PLS uptake and facilitate sharing of new medical research with lay audiences.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

What do you need to know?

Plain language summaries (PLS for short) explain medical research in a clear and understandable way. We found ways to improve how PLS are developed to help people understand medical research publications. See Additional file 1 for a graphic PLS.

Why did we do this study?

Many people struggle to understand medical research because authors use complex words in research publications. Currently, PLS vary in style and format and most research publications do not have a PLS.

What did we do?

We invited 29 experts from various organizations who develop, publish, read, or fund PLS to take part in this study. We asked them what issues they thought are preventing research publications from having a PLS, and how we could solve these issues.

What did we find?

Most groups agreed on the top 10 issues we need to look at to improve PLS so that more publications have a PLS. There are several ways to improve how PLS are developed. Guidelines on which publications should have a PLS and what they should include are urgently needed. People who think PLS are important need to request them to help make sure they are regularly included in research publications. We also need clear ways to share PLS, so people with an interest in medical research can find and read them.

Introduction

The term plain language summary (PLS) refers to a short synopsis of a piece of research presented in a way that is accessible to a broad readership, including nonspecialist healthcare professionals (HCPs) and lay audiences, including patientsCitation1. Lay audiences are interested in medical developments and seek information from scientific journalsCitation2,Citation3. Evidence supports the use of PLS for effectively communicating research to these broader lay audiences and shows that PLS can improve understanding of research resultsCitation4–9. Understanding the implications of new data can help patients and their healthcare teams put research into context and can facilitate shared decision-makingCitation2. Effective communication through PLS may extend the reach of medical research, helping to avoid misunderstanding and misinterpretation of complex data and to counter misinformation.

This study focused on PLS associated with publications in peer-reviewed journals and presentations at scientific congresses (also known as conferences), and not lay summaries of clinical trials (to inform patients on trial results) that are mandatory in the European Union as part of the Clinical Trial Regulation EU No. 536/2014Citation10. There is growing interest in developing PLS of company-sponsored medical research, which covers research sponsored or supported by pharmaceutical, medical device, diagnostics, and biotechnology companies. Such companies are increasingly including PLS in their publication plans but with inconsistent approaches. Questions remain regarding how to develop PLS effectively. Furthermore, given the highly regulated environment in which pharmaceutical companies operate, some are concerned about the appropriateness of supporting publications that contain content that is directed at audiences beyond HCPs.

At the time of writing this article, there is no universal guidance to establish PLS as an appropriate enhancement for medical publications, although a minimum standard for PLS has recently been proposedCitation11. The absence of guidance is likely to be a contributing factor to the slow uptake of PLS by some companies and publishers, despite the benefits that PLS can bring to interested audiences. Organizations such as Cochrane have embraced this innovation in publications more readily, but have struggled to deliver consistent, high-quality PLSCitation12,Citation13. Further guidance is needed for authors, journal editors, publishers, peer-reviewers, pharmaceutical companies, and other groups to encourage PLS uptake and ensure best practice for developing and publishing these important summaries.

The objectives of this study were to provide multi-stakeholder perspectives on key issues relating to developing and publishing PLS of company-sponsored medical research. The study was endorsed by the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP), as a leading global authority on the ethical and effective communication of medical researchCitation14.

Our aim was to provide insights and build an evidence base that could be used to inform future relevant industry-wide guidelines that may provide direction on PLS, such as the forthcoming update of the Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelinesCitation15. We present the approach taken in this 2-part study to gain the views from diverse professional stakeholder groups and describe the key thoughts of these groups on how we can move PLS forward. In the first part of the study, we identified key questions to be addressed using a modified Delphi approachCitation16. In the second part, we identified key considerations and highlighted opportunities and potential barriers for developing PLS of company-sponsored medical researchCitation17,Citation18.

Methods

Study design

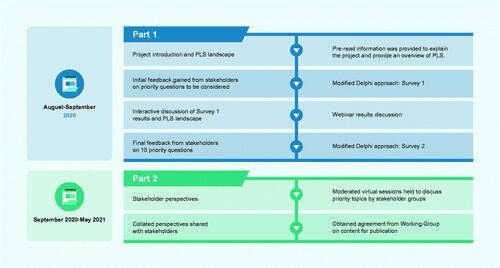

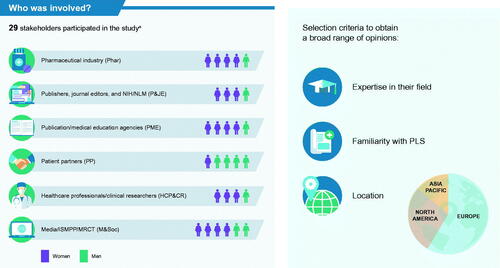

We established a Working Group (see acknowledgements) comprising experts with collective, extensive experience in PLS. We used a prospective, 2-part, mixed-method study design (). Invitations were sent by email to stakeholders representing 6 different professional sectors: pharmaceutical industry (Phar); publishers, journal editors, and National Institutes of Health/National Library of Medicine (P&JE); publication/medical education agencies (PME); patient partners (experienced patient advocates; PP); HCPs and clinical researchers (HCP&CR); media, ISMPP, and the multi-regional clinical trials center (M&Soc). We selected a diverse group of stakeholders based on expertise in their field, familiarity with PLS, and location, which allowed us to gather a broad range of opinions from different geographies. All participating stakeholders provided their own insights and were not representing any organizations. They all provided consent for their data to be published.

Part 1: modified Delphi approach

To initiate the study, we provided pre-read information presenting an overview of the study and the current PLS landscape (slide deck with audio) by email to the stakeholders in August 2020. This pre-read information provided all stakeholders with the same evidence-based summary on PLS, with the aim of giving them the confidence to actively participate in the stakeholder group discussions.

During an online discussion and subsequent email correspondence, the Working Group identified 14 key questions focused on the areas that need to be addressed to facilitate the development and publishing of PLS. These initial 14 questions were shared with the stakeholders and a modified Delphi approach was used to prioritize the 10 key questions. Stakeholders were also given the option of submitting additional questions for consideration by the Working Group. The first survey was carried out between 27 August and 8 September 2020. Following interactive online discussions of Survey 1 results and the PLS landscape (10 and 11 September 2020), stakeholders were given the opportunity to reconsider which questions they would prioritize. We carried out a second survey between 11 and 21 September 2020 to obtain final feedback from the stakeholders on the priority questions to be considered. Weighted average score was used to provide an average ranking for each answer choice to rank the survey questions in order of priorityCitation19. The prioritized 10-question framework was then used to structure the stakeholder discussions and to collate evidence on the key challenges and opportunities to inform best practice for PLS.

Part 2: stakeholder meetings

Between 23 September and 19 November 2020, we held virtual sessions with each stakeholder group, moderated by members of the Working Group (3 h; some split over 2 sessions), to discuss the priority questions. Separate group sessions were held to ensure each stakeholder group was able to clearly present their viewpoint, without influence from other stakeholders. Where it was deemed helpful to achieve consistency, the moderators provided some discussion prompts e.g. the ‘Type of Information’ list considered in question 1. Each group was also asked to consider what they thought were the 3 key opportunities for their sector to accelerate PLS uptake. Insights were collated and discussed within the Working Group to ensure agreement on the key findings for this publication.

Results

Overall, 29 stakeholders took part in the study, representing different professional sectors and geographies (). Response rates were high for both surveys: Survey 1 = 69%; Survey 2 = 90% (Supplemental Figure 1)Footnotei. There was strong alignment among the diverse stakeholders on the priority questions relating to PLS (Supplemental Figure 2). Eight respondents suggested additional questions, however, these were deemed by the Working Group either to be out of scope or already covered in the 14 pre-identified key questions. There were no major changes in question priority between the 2 surveys.

Figure 2. Expert stakeholders who participated in the study. aOne stakeholder accepted the invitation for the project but was not able to complete either survey or participate in the stakeholder discussion sessions. Abbreviations: HCP&CR, healthcare professionals and clinical researchers; M&Soc, media, International Society for Medical Publication Professionals, and the multi-regional clinical trials center; Phar, pharmaceutical industry; P&JE, publishers, journal editors, and National Institutes of Health/National Library of Medicine; PLS, plain language summary; PME, publication/medical education agencies; PP, patient partners.

Moderated virtual sessions to discuss priority questions were attended by 27 of 29 stakeholders (1 stakeholder from Phar and 1 stakeholder from PP did not participate). The topics are reported here in a linear format to align with the 10 priority questions. However, views are not verbatim from stakeholder discussions as groups often discussed elements of different questions at the same time or returned to questions throughout the discussions. Viewpoints captured are based on the consensus of the stakeholder group. Occasionally there were individual minority views within a stakeholder group.

Question 1: What information must, and must not, be included in a PLS?

Overall, the groups agreed that a PLS should be written as a standalone communication with its own structure and communication goals and with the primary target audience in mind—not as a teaser for the full publication. Items that stakeholders thought should be included in a PLS were discussed by each group (). From a patient perspective, the most important information to include in a PLS was results, conclusions, and recommendations. However, the content of the PLS will depend on the specific context (e.g. the study, type of data, what the condition is) so it may vary.

Table 1. Key information that should be included in a PLS.

There was broad agreement that only results from the study that are in the full publication should be included in the PLS. If additional interpretation of the data is required for patients, this should also be included in the main article. However, including information in the PLS to support health literacy and understanding of the context and meaning of the results for a lay audience could be helpful. For example, providing brief information on what is known about the therapy to date or explaining a complex mode of action were considered helpful additions by most groups. Standardized lexicons for medicines and therapy areas could help accelerate the PLS development process, provide consistency, facilitate discoverability, and improve understanding.

‘…PLS should standalone, not be a “teaser”’ HCP&CR

‘I think context is really important… but ALSO what are we adding with this knowledge?’ M&Soc

‘Patients want to know why the information is useful to them, and what can they do with it’ PP

Question 2: Who are the target audiences for PLS, and why?

Most stakeholders felt that patients and carers should be considered as the primary, but not only, audience for PLS (). Various perspectives were raised by different stakeholder groups.

Figure 3. Who are the key target audience for PLS? Abbreviations: HCP, healthcare professional; PAG, patient advocacy group; PLS, plain language summary.

It is key to differentiate between primary and secondary audiences, so PLS are written with the primary target audience in mind (PME).

Having multiple versions of tailored PLS for different audiences would be impractical, so a primary audience should be defined, and this should be patients/carers (PP, M&Soc).

Access to credible and understandable data is key for patients (HCP&CR).

Identifying patients as the target audience may raise compliance issues for some companies (Phar).

Patients accessing PLS are likely to be more educated and empowered patients (Phar).

There is a need to democratize data and provide results in a way that is accessible for broader patient populations such as research participants who should also be considered an audience for PLS (M&Soc).

Anyone who is online and who can perform an internet search for PLS is a potential audience (P&JE).

There was consensus from all groups on the value of PLS for other audiences beyond patients, including HCPs, the general public, and the media. HCPs often have limited time or may be non-specialists (e.g. in rare diseases) and scientific publications, including abstracts, often contain highly technical language (P&JE, Phar). Although not their primary purpose, PLS may pique interest by providing a snapshot, so HCPs then go on to read the full primary publication (HCP&CR). However, it was acknowledged that HCPs also have other ways to access data, such as short summaries and key points, so they should not be viewed as the primary target audience. In addition, PLS were viewed as having potential as a useful tool for facilitating improved communication and shared decision-making between HCPs and patients, as not all HCPs are well trained in lay communication skills (HCP&CR, PME). Finally, PLS were recognized as important to the media as a credible and comprehensible source for providing news to lay audiences and to help counter misinformation (HCP&CR).

‘Are patients a target audience? No, patients are the target audience. If it’s in plain language, anyone else should be able to understand it’ PP

‘I can’t think of anything a patient would want to see in a PLS that a journalist wouldn’t and vice versa’ M&Soc

‘If you don’t know who you’re writing for, how do you know what to say?’ HCP&CR

‘GPs are so time poor – PLS are a very valuable patient communication tool’ HCP&CR

Question 3: What is/are the optimal format(s) for a PLS?

Several key considerations were identified by the stakeholder groups when considering the optimal format for PLS.

Key factors when considering the optimal format for a PLS

• Health literacy best practices

• Structured PLS with a standardized question-and-answer format to make data accessible

• Specific target audience preferences/needs

– For example, pediatric audiences may prefer a cartoon format; audio options may be appropriate for people with visual impairments

• Need for translation into other languages

– Text-only PLS would be best option if translation is required

• Desire to share via social media

– Visuals are preferred to text-only formats for social media

• Journal or congress options/requirements

• Budget available

– Short text-only PLS are the most cost-effective

• Extent and type of data

– Different studies/data types may suit different PLS formats

There was general agreement among stakeholder groups that a mix of graphics with text is the optimal format for most PLS, rather than text or graphic only. The use of both graphics and text ensures that complex information is portrayed clearly (graphics), and that the content is easily retrieved through search engines (text). ‘Junk’ visuals that do not contribute to understanding should be avoided. 'Full infographic' formats were considered to be optimal for individuals to share on social media, as they are highly visual and can contain all the necessary information and context. Video formats were discussed, although it was noted that information within them can be difficult to find using an internet search engine unless a text script is also provided. Some groups noted that a good option would be to have a short text-only PLS (indexed on the PubMed database) along with a more visual detailed summary. The optimal length of these more detailed summaries was debated, but stakeholders were reluctant to provide specific recommendations as it will vary depending on the format, and purpose. The overall consensus was to ensure that all relevant content and context was included, whilst avoiding unnecessary detail. The PLS should be shorter than the manuscript itself, with between 1 and 3 pages proposed to fully describe the key content relevant to PLS audiences.

‘Relevant visuals can be helpful to bring data to life and help readers with lower literacy levels’ PP

‘It's good to have words on paper, but personally I also like infographics’ PP

‘Most researchers do tweet their papers and threads to summarise and if this was an easy graphic that’s great as it can be seen in its whole and in its context’ M&Soc

‘Important to have a step to think about the audience (for the PLS) and how the format will fit the audience’ PME

‘If hosted by a journal, format will probably be dictated by the journal’ HCP&CR

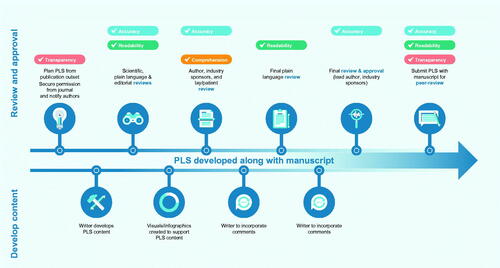

Question 4: What is the optimal PLS development/review/approval process?

When developing a manuscript, PLS should be considered from the outset, as this may influence the choice of target journal. Most stakeholders felt that PLS should be developed along with the manuscript and incorporated into the same journal submission, so it is included in the peer-review process. However, one group (Phar) thought that developing a PLS after manuscript acceptance was also appropriate, even if there were cost implications for managing an additional round of peer-review.

To ensure quality, support may be needed from individuals skilled in plain language writing and/or creating visuals, as many authors do not have specific lay writing skills. Cost implications of PLS (e.g. medical writing support and creating quality visuals) should be included up front in grant applications.

For standalone PLS (see question 10), at least one of the original authors should be involved in developing and reviewing the content to ensure accuracy of interpretation of the original publication. One group (Phar) felt that if there were no new data or interpretation then there should be no new authors on the PLS versus the original article. Co-authors of the original publication should be included on a courtesy review of the PLS.

All groups agreed that, as a minimum, the final PLS should be approved by the lead author of the original publication. For PLS developed post journal acceptance, this would help streamline the review process while still ensuring that the PLS reflects the content of the article. However, some groups (P&JE, PP) thought that all authors should approve the final PLS. All reviewers of the PLS (including industry and authors) should receive some training in health literacy principles to ensure best practice for PLS development. The more authors review and approve PLS routinely as part of the publications they develop, the more skilled they will become. It was considered important to include a review by a lay person or patient representative to check comprehension—these reviewers may or may not have the condition under discussion. Key factors to consider when identifying the ideal lay reviewer include the reviewer’s level of expertise and lived experience with a health condition. Lay reviewers should be offered appropriate payment for their expertise and time. Based on these insights we have developed an example process for PLS of journal publications that considers accuracy, transparency, comprehension, and readability ().

Figure 4. Overview of an example content development, review, and approval process for PLS of journal articles developed with medical writing support. Abbreviation: PLS, plain language summary.

‘It is an emerging area, journals are convincible’ [relates to flexibility of journals – even if the author guidelines don’t mention PLS its worth discussing with the journal editors] Phar

‘These are plain-language summaries of published journal papers or posters, essentially it’s research, we’re not looking actually to disseminate brand new information, we are looking to use a new form of explaining information that already exists, so for me you just put the new way alongside what already exists. I’m not trying to change all the produce available in a supermarket’ PP

Question 5: What is needed to ensure PLS are considered to be appropriate vehicles that accompany scientific publications, and are not medical educationFootnoteii or promotional materials?

Most groups indicated that perception of 'promotion or direct to consumer communications' represented the main barrier/risk to developing company-sponsored PLS. Discussions centered on ensuring PLS are credible, and that the process involved in developing PLS is transparent. Most groups felt that the traditional peer-review process is an important way to validate and confirm the accuracy and interpretation of the PLS content, and thereby avoid the perception of bias. Including PLS as part of the peer-review process could help differentiate these scientific summaries from promotional materials and overcome barriers such as PLS being considered promotional or subject to ‘cherry picking’ which publications have PLS. To enhance transparency, some groups (Phar, M&Soc) expressed a preference for PLS to undergo simultaneous peer-review by journals and be published alongside the research article. In the pharmaceutical industry setting, publication alongside the article can facilitate subsequent use and sharing of the PLS. PLS that are published separately from the related research publication/data should also undergo rigorous peer-review (see question 10). Although PLS should be visually appealing, it was considered important to avoid the use of product branding (e.g. company colors, logos) and links to commercial websites, which may be perceived as a step in the direction of promotion.

While there was some discussion on the potential value of the Congress Editorial Board review of abstract data, all stakeholders agreed that this did not constitute a full peer-review, as usually no specific comments on the content are provided. However, given the rapid and broad dissemination of scientific data via press release during a congress, the need for abstract PLS (APLS) of congress data that have not yet been fully peer-reviewed was recognized. APLS can provide timely information to lay audiences attending scientific congresses, particularly for those with a patient track. All stakeholders felt that APLS should be restricted to information in the abstract only, clearly stating that the data within are preliminary and that the findings have not been through the full peer-review process.

‘Need to consider why we are doing these. Is it to have another deliverable to the publication plan or to get timely and credible information (understandable and accessible) to patients and public’ PME

‘PLS associated with pharma will always be at risk of bias if not reviewed by a journal’ HCP&CR

Question 6: Where and how should PLS be published to ensure optimal reach and discoverability?

All groups agreed that PLS for journal articles should be free to access, even if the full paper is not open access, and linked to the original article. There was support for the PLS to sit alongside the abstract in PubMed (in addition to other options), although all groups acknowledged that PubMed is not an ideal repository for material aimed at lay audiences, as it is designed primarily for scientific audiences. Including a PLS within the article (as a figure or supplemental material) was viewed as a good option provided a clear easy-click link was included to highlight the presence of, and to provide direct access to, the PLS. If a journal does not have the facility to host PLS and if agreed by the journal editor, third-party platforms (such as Figshare) were viewed as a useful resource by multiple stakeholders. These platforms can provide a permanent and citable identification (digital object identifier, DOI), are free to post material to and share from, include options for tagging and sharing graphics, and are familiar to many lay audiences.

Social media was considered an important tool in the dissemination of PLS, but copyright restrictions and pharmaceutical industry guidelines relating to promotion need to be adhered to. Pharmaceutical industry employees are often restricted regarding social media use, and these stakeholders indicated that they need more guidance on using PLS in this regard. Journals, patient advocates, and academic authors often have greater opportunity to share information using social media channels.

Stakeholders supported access to APLS via QR codes or links on posters/oral presentations at congresses. The QR code on a poster linking to the APLS should be obvious (PP). All groups agreed that APLS should have a limited life span to prevent data inconsistencies with subsequent peer-reviewed publications. There was some debate on the use of company websites to host APLS. While some groups (Phar, HCP&CR) felt the companies have an obligation to share information, others had concerns over provision of preliminary non-peer reviewed information to non-HCP audiences (PME, M&Soc).

‘Disseminate [PLS] as widely as possible! Go for everything you can including a PLS repository if available!’ M&Soc

‘The journal article, the abstract and the PLS should be alongside each other online, so that the reader can select the one they would prefer to look at’ PP

‘What is the patient's ‘world’ - where would they go to find this information - how can it be searched for? This is where they should be stored’ Phar

Question 7: How can the reach, quality, and value of PLS be measured?

There was much debate within all stakeholder groups about how to assess the overall value of PLS. While all stakeholders agreed that some form of evaluation is needed, they recognized that value is multifactorial and therefore difficult to define and measure. Several different approaches were proposed to assess key attributes that contribute to value, including reach and quality.

Most groups suggested the use of available online metrics to measure the reach of PLS, including the Altmetric tool, Google metrics, and social media (e.g. Facebook, Twitter) mentions. It would be important to have a benchmark, so that metrics are compared against a control group. It was also noted that it is important to define the audience to find out if the ‘right people’ are reached. Metrics could be used to gauge discoverability—who is reading and who is sharing the PLS online/on social media. Additionally, some publishers generate heat maps to assess the value of publication enhancements, and these may be of use to determine what content people are accessing when the PLS and related article sit together. This information could also be used to understand the extent to which PLS are being accessed and to measure geographical reach.

Quality was discussed in terms of readability and ease of understanding. Most groups suggested some form of readability assessment could be used to assess quality, with most suggesting the use of online readability tools. However, one group (Phar) noted that there could be confidentiality concerns if non-licensed versions were used. Several groups noted that readability tools have flaws so should not be used as the only measure of quality, and caution should be taken if setting specific targets or scores. A few groups suggested asking readers directly to complete questions/ratings through a clickable link on the PLS. This link could help assess quality, query whether the PLS was understood or useful, or use a simple thumbs up/down 'voting' approach. A traffic light system was also considered a useful approach to clearly indicate the quality of the evidence within the PLS. Focus groups were also proposed as a way of obtaining more detailed feedback and assessing the level of understanding (M&Soc, Phar).

‘If the messages from the summary end up in the media then that is the sign that it is working’ M&Soc

‘Is the message being delivered the same as the one being received?’ HCP&CR

‘The outcome measures aren’t simple – you’re not trying to change their behaviour or believe a particular thing; you’re trying to inform them…and measuring how informed someone is isn’t a simple Altmetric type statistic’ M&Soc

‘Focus groups are quite useful. Won’t give you a sense of numbers but will give you some depth on how effective materials are’ M&Soc

‘Look at whole picture – don’t let specific scores dictate’ [relates to readability tools] PME

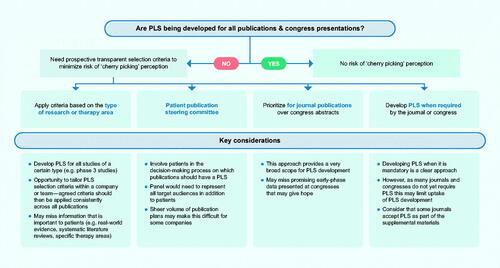

Question 8: What process should be followed to select publications that will have a PLS to avoid the perception of selection bias by the sponsor?

The stakeholders felt that, ideally, all publications should have a PLS mandated by the journal; however, all groups acknowledged the cost and resource implications of this approach. Journals have a role in encouraging PLS but are unlikely to make them mandatory in the foreseeable future due to demand and cost. All stakeholders agreed that there were no simple criteria, or single approach, for selecting which publications should have PLS that would work in all situations. Guidance on the factors that sponsors should consider to avoid the perception of 'cherry picking' would be welcome. Most groups thought that PLS for research publications should be prioritized over PLS for congress abstracts due to the credibility of the peer-reviewed data.

Potential approaches for selecting which publications should have PLS were considered but all of these had limitations (). Using criteria based on type of data (e.g. phase 3 studies) may miss information that is important to patients (e.g. real-world evidence, patient-reported outcomes, systematic literature reviews) and promising early-phase data that may give hope. Using criteria based on therapy area (e.g. only rare diseases) may miss important indications. If steering committees were used to guide the selection of publications for PLS, the committee should ideally include representatives from all key audiences, not just patients. Consequently, there were differing viewpoints on the feasibility of such steering committees: Phar indicated that a steering committee should represent all key lay audiences, whereas HCP&CR felt it would be difficult to get a representative group. M&Soc were in favor of steering committees, as this would provide an independent assessment and 'seal of approval’, but PP felt this was not an option due to the sheer volume of publication plan outputs.

Figure 5. Potential approaches to select which publications should include a PLS. Abbreviation: PLS, plain language summary.

The current unknown value of PLS was indicated by one group (PME) as a barrier for selecting which publications should have a summary, although it was noted that this evidence is starting to emerge. Cost was recognized as a barrier and even if guidance on selecting which publications should have a PLS becomes available it may be difficult to enforce (Phar). There was no consensus on which studies should have PLS mandated, and the difficulties of requiring PLS for all publications were acknowledged.

‘Strongly encourage – have a defined position on how and why they will do this in their process or SOP is key’ [Avoiding selection bias] PME

‘We don’t want to do anything that would be compulsory, but I do think it would be good to encourage it, eg, add PLS into abstract submission site and guidelines as an option’ P&JE

‘Can’t they be mandatory for everything? What we’ve been discussing sounds relatively achievable. As an author you’re spending hours writing it anyway so to add this isn’t a huge extra ask. If we make it easy to do then why can’t we mandate it?’ M&Soc

Question 9: How can PLS meet the needs of non-English–speaking audiences and account for different cultures?

The main issues identified by the stakeholder groups were optimizing the process for translating PLS and determining which languages should be prioritized. In neither case did the groups reach a clear consensus. Most groups identified that it was important to consider the process for translation. Owing to the wide variation in the quality of automated translation services, some groups (Phar, HCP&CR) recommended avoiding these tools. There is a need to check differences/nuances between common languages in different countries, which may not be picked up by automated services. Other groups (PP, P&JE) highlighted that if the text was truly in plain language, then this would facilitate translation into other languages and in future, automated translation of PLS may be possible.

There was no general agreement on which languages PLS should be translated into. However, if PLS are only published in a limited number of languages, possible options to consider were prioritizing languages of populations with high disease prevalence or where the topic is of relevance to a specific group, the study participants, and the region(s) in which the study was conducted.

Some groups discussed features to include in PLS to ensure they are easy to translate and culturally appropriate, for example, text is easier to translate than visuals. Appropriate icons and figures were viewed as important (Phar) but should be used carefully. HCP&CR suggested that neutral icons should be used in PLS. However, icons may require context and can be audience specific, so it is very difficult to develop guidelines around icon use and more research is needed (M&Soc). Working with local employees who have cultural awareness or with the target/end audience could help ensure that appropriate icons are used in PLS (PME). When considering budgets for PLS, one group (PP) believed it was more important to have more PLS, than to have translations or more diverse icons, as developing PLS in the first place is an important step to improving accessibility.

‘Making sure there are no barriers for translation is what the journals should do’ P&JE

Question 10: What criteria should be met for developing a PLS for an article already published?

In general, there was support for the idea of retrospective PLS for previously published articles. There were differing viewpoints on the peer-review process for this type of PLS, with some groups (Phar, PP) considering this essential, while others thought they could be reviewed by the journal editor (P&JE, PME). One group (M&Soc) suggested that peer-review may not be required if the original authors were involved and there were no new data or interpretation in the PLS. It is important that retrospective PLS are not tagged as errata in PubMed.

Key considerations for developing PLS for an article already published:

Include a link to original article

Involve the original authors

PLS should be peer-reviewed

Have objective criteria for selecting when to develop retrospective PLS

Standalone PLS that are published by Future Science GroupCitation20 were also discussed. These are regarded as a secondary publication per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) guidelines and require approval from the publisher of the original article, for courtesy and to avoid copyright issues. However, one group (Phar) raised concerns about the possibility of combining data from 2 or more prior publications into a standalone PLS.

‘Publishing a PLS post the original publication is NOT an erratum!’ PME

What are the key opportunities for your stakeholder group to progress PLS?

Each stakeholder group considered what the key opportunities were for their sector for progressing PLS (). While the potential value of PLS is well recognized, further advocacy is needed by target audiences to ensure PLS become an established part of publications describing company-sponsored research. PLS are recognized as being an acceptable publication enhancement, and having broad guidelines on PLS, potentially similar to ICMJECitation21 and GPPCitation15, could address potential risks and barriers for PLS. There is a lack of standardized procedures for PLS, for example, selection guidance on which publications should have a PLS and lack of clarity on optimal format and development/review process. A standard industry-wide quality checklist may be useful for PLS, but this would need to be quick and easy to use. Ideally, a more holistic approach should be taken rather than using specific cutoff values for assessments such as readability. One group (PP) suggested that a CONSORT-style checklist with best practice recommendations could maintain a consistent style and level of quality for PLS.

Table 2. Opportunities to overcome real or perceived barriers to the uptake of PLS.

Further dissemination of PLS is key to reach target audiences, however, there are limited platforms for ensuring dissemination of PLS. The ideal scenario would be to have a central, patient-friendly repository to house all PLS (with each linking back to its original article), but stakeholders acknowledged that this would be a huge task requiring extensive resources and funding.

‘Consistent industry-wide guidance needed. We know that people want that and it will be valuable’ PME

Conclusions

We obtained perspectives from a diverse group of stakeholders with significant expertise from different sectors on the key considerations, opportunities for, and potential barriers to driving PLS of publications detailing company-sponsored research. The data were generated using a robust, prospective methodology to provide an evidence base to help inform future guidance on PLS. Stakeholders identified and debated the top 10 questions relating to PLS. Although there were some differences in priority ranking of these questions between the stakeholder groups, there was also much alignment on how we can optimize PLS. The stakeholders identified several key considerations for PLS to ensure these are effective and nonpromotional. They also highlighted key opportunities to accelerate PLS uptake and provided a broad insight into the real and perceived barriers to PLS identified by each of the groups. Each emerging theme presents a possible action behind which stakeholders can mobilize towards the common goal of accelerating PLS uptake. We acknowledge that these findings reflect insights from a limited number of stakeholders (29 stakeholders; 19 women) and look forward to additional perspectives from a broader range of stakeholders involved in PLS to increase the frequency and value of these important summaries.

PLS are publications, be that as part of a research article or a standalone publication. The scientific rigor of their evidence can be gauged on whether they are peer-reviewed—some are, some are not. Publications/PLS are the authors’ (not the sponsor’s) communication of research findings to audiences via congress and journal channels that have been recognized for centuries as being appropriate for scientific exchange. Any sponsor wishing to further the reach and impact of their scientific research by encouraging authors to develop PLS should be applauded. Furthermore, sponsors are encouraged to consider their responsibility to translate science for broad use across multiple stakeholders, in support of use in healthcare decision-making and in line with equity, diversity, and inclusion principles. If all PLS are free to access and search engine optimized, then they would be discoverable by a broad range of audiences through a simple internet search. As authors, we suggest that to restrict scientific exchange to qualified HCPs is an outdated concept that perpetuates paternalistic approaches and is not consistent with equity, diversity, and inclusion in healthcare.

We hope that the key insights from this study will inform industry-wide guidelines on PLS and accelerate the generation of these important publications to facilitate sharing of medical research to broad audiences. While our study focused on PLS for company-sponsored medical research, we believe that many of the insights reported may also be relevant to PLS for research funded by other means.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by ISMPP, Envision Pharma Group, and McCann Health Medical Communications.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Dawn Lobban, Amanda Boughey, Lauri Arnstein Williams, and Anne-Clare Wadsworth are employees of Envision Pharma Group. Karen Woolley is a consultant for Envision Pharma Group. Jason Gardner, Mary Gaskarth, Jane Blyth, Andrea Plant, and Karen King are employees of McCann Health Medical Communications. Both companies are involved in providing medical writing support, including for PLS, for the pharmaceutical industry. Robert Matheis has no disclosures to declare.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, and critical review of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and provided final approval of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material: PLS Graphic

Download PDF (724.3 KB)Supplemental Material: PLS Perspectives

Download PDF (317.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the stakeholders who took part in this study for their valuable input, including those who agreed to be named here (4 were lost to follow-up). Phar: Avishek Pal, MSc (Novartis Oncology); Angela Sykes, MPhil (Pfizer); Linda Feighery, PhD (UCB Pharma); Maya Shehayeb, PharmD (Amgen Inc.). P&JE: Kelly Soldavin, BS (Taylor & Francis Group); Laura Dormer, BSc (Future Science Group); Professor Ana Marusic (Cochrane Croatia, University of Split School of Medicine); Nicholas Miliaras, PhD (U.S. National Library of Medicine). PME: Dan Bridges, PhD (Nucleus Global); Professor Karen Woolley, PhD (Consultant, Envision Pharma Group); Lauri Arnstein Williams, MD (Envision Pharma Group); Karen King, PhD (CMC Affinity, McCann Health Medical Communications); Andrea Plant, PhD (Caudex, McCann Health Medical Communications). PP: Richard Stephens, MA (Patient advocate and Co-Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Research Involvement and Engagement); Simon Stones, PhD (Patient advocate, Envision Pharma GroupFootnoteiii). HCP&CR: Lucas Litewka, MBA (Director USC Clinical Trials); Sandra Cornett, PhD (The Ohio State University College of Nursing); Professor Helen Reddel (The Woolcock Institute of Medical Research and The University of Sydney); Joanna Siegel, ScD (Director, Dissemination and Implementation, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute). M&Soc: Robert Matheis, PhD (ISMPP); Lynnette Hoffman, BSc (Australasian Medical Writers Association); Lawrence McGinty, BSc (Chair, Medical Journalists’ Association); Alexandra Freeman, DPhil (Winton Centre for Risk & Evidence Communication, University of Cambridge); Sylvia Baedorf Kassis, MPH (Multi-Regional Clinical Trials Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard); Jane Symons (journalist, media consultant, and vice chair of the Medical Journalists’ Association).

This study was led by the ISMPP PLS Perspectives Working Group: Dawn Lobban, Amanda Boughey, Lauri Arnstein Williams, Anne-Clare Wadsworth, and Karen Woolley of Envision Pharma Group; Jason Gardner, Mary Gaskarth, Jane Blyth, Andrea Plant, and Karen King of McCann Health Medical Communications, and Robert Matheis of ISMPP.

Data collection and medical writing support was provided by Jacqui Oliver, PhD, at Envision Pharma Group and was funded by Envision Pharma Group.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Dawn Lobban, upon reasonable request.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

i 2 of the 29 stakeholders had not yet enrolled when Survey 1 was issued.

ii This means materials that are developed by the company sponsor and require review and approval by the sponsor for communicating medical information directly to the intended audience.

iii Participant was not an employee of Envision Pharma Group when this research was conducted.

References

- FitzGibbon H, King K, Piano C, et al. Where are biomedical research plain-language summaries? Health Sci Rep. 2020;3(3):e175.

- Pushparajah DS, Manning E, Michels E, et al. Value of developing plain language summaries of scientific and clinical articles: a survey of patients and physicians. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2018;52(4):474–481.

- Georgieva A, Nuottamo N, McNamara M, et al. Patient information needs and relevant channels. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(sup1):23.

- Bredbenner K, Simon SM. Video abstracts and plain language summaries are more effective than graphical abstracts and published abstracts. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0224697.

- Chapman SJ, Grossman RC, FitzPatrick MEB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of plain English and visual abstracts for disseminating surgical research via social media. Br J Surg. 2019;106(12):1611–1616.

- Huang S, Martin LJ, Yeh CH, et al. The effect of an infographic promotion on research dissemination and readership: a randomized controlled trial. CJEM. 2018;20(6):826–833.

- Lindquist LA, Ramirez-Zohfeld V. Visual abstracts to disseminate geriatrics research through social media. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(6):1128–1131.

- Stricker J, Chasiotis A, Kerwer M, et al. Scientific abstracts and plain language summaries in psychology: a comparison based on readability indices. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231160.

- Kerwer M, Chasiotis A, Stricker J, et al. Straight from the scientist’s mouth—plain language summaries promote laypeople’s comprehension and knowledge acquisition when reading about individual research findings in psychology. Collabra: Psychology. 2021;7(1):18898.

- Clinical trials - Regulation EU No 536/2014. [cited 8 April 2021]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/human-use/clinical-trials/regulation_en.

- Rosenberg A, Baronikova S, Feighery L, et al. Open Pharma recommendations for plain language summaries of peer-reviewed medical journal publications. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021:1–2. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2021.1971185

- Cochrane Methods. Methodological expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews. Standards for the reporting of plain language summaries in new Cochrane Intervention Reviews 2013. [cited 25 June 2021]. Available from: https://methods.cochrane.org/sites/default/files/public/uploads/pleacs_2019.pdf.

- Jelicic Kadic A, Fidahic M, Vujcic M, et al. Cochrane plain language summaries are highly heterogeneous with low adherence to the standards. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:61.

- ISMPP. [cited 26 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.ismpp.org/.

- Battisti WP, Wager E, Baltzer L, International Society for Medical Publication Professionals, et al. Good publication practice for communicating company-sponsored medical research: GPP3. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):461–464.

- McMillan SS, King M, Tully MP. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(3):655–662.

- Gardner J, Lobban D, on behalf of ISMPP PLS Perspectives Working Group. Plain language summaries of publications: diverse stakeholders identify key opportunities to accelerate uptake [oral presentation]. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(sup1):15.

- Lobban D, Gardner J, Matheis R, et al. Plain language summaries of publications: what key questions do we need to address? Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(sup1):32–33.

- Ranking question. [cited 1 Oct 2021]. Available from: https://help.surveymonkey.com/articles/en_US/kb/How-do-I-create-a-Ranking-type-question.

- Dormer L, Walker J. Plain language summary of publication articles: helping disseminate published scientific articles to patients. Future Oncol. 2020;16(25):1873–1874.

- International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing, and publication of scholarly work in medical journals. [updated December 2019; cited 4 August 2021]. Available from: www.icmje.org/recommendations.