Abstract

Objective

To examine the healthcare costs associated with colorectal cancer (CRC) screening and the frequency and costs of events potentially related to colonoscopy among average-risk adults.

Methods

In this cohort study, adults (ages 50–75 years) with CRC screening between 1/1/2014 and 6/30/2019 (index = earliest test) were selected from the IBM MarketScan Research databases. Individuals at above-average risk for CRC or with prior CRC screening were excluded. Frequency of utilization was reported by screening type: colonoscopy, fecal immunochemical test (FIT), fecal occult blood test (FOBT), multi-target stool DNA (mt-sDNA). For colonoscopy, frequency and costs of potential events were reported overall, by event type, and by an individual event in the 30 days after colonoscopy.

Results

Among the 333,306 average-risk adults, colonoscopy was the most common CRC screening modality (70.6%), followed by FIT (17.7%), FOBT (8.1%), and mt-sDNA (3.2%). The mean cost of a colonoscopy procedure was $2,125 and the mean out-of-pocket costs were $79. Serious gastrointestinal (GI) events were observed in 1.3% of individuals with colonoscopy, 1.9% had other GI events, and 1.2% had an incident cardiovascular event. Mean event-related costs were $2,631 among individuals with a serious GI event, $1,774 among individuals with any other GI event, and $4,234 among individuals with a cardiovascular event.

Conclusions

This study provides updated and more detailed information regarding the costs of CRC screening and potential colonoscopy events based on a comprehensive review of a robust claims dataset.

Introduction

In 2021, 149,500 incidents and 52,980 fatal colorectal cancers (CRCs) are projected, making this cancer the third most common and second most lethal type of malignancy in the United States (US)Citation1. CRC screening has been consistently shown to reduce disease-related morbidity and mortalityCitation2,Citation3. Therefore, national organizations, such as the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Cancer Society, recommend population-level CRC screening for average-risk adults, starting at age 45 or 50 and continuing through age 75 yearsCitation4,Citation5. Guidelines from the American Cancer Society provide a qualified recommendation to start screening at age 45 in order to interrupt or reverse the unfavorable trends emerging among younger adultsCitation5.

Options for average-risk CRC screening include colonoscopy every 10 years, CT colonography, double-contrast barium enema (DCBE), or flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) every 5 years, multi-targeted stool DNA testing (mt-sDNA) every 3 years, and fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) or fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) every year based differing attributes and acceptance of the endorsed modalitiesCitation5. For example, screening with colonoscopy allows for detection and removal of precancerous polyps and early-stage cancers; however, it is associated with unpleasant bowel preparation, high costs, and potentially serious gastrointestinal (GI) eventsCitation6–8. By contrast, stool-based tests are non-invasive and less costly but require colonoscopy follow-up for any positive resultCitation9,Citation10.

Given the multifactorial nature of CRC screening decision-making, this study sought to provide an updated analysis of the costs of average-risk screening to better inform planning and application of systematic early detection programs. More specifically, we identified a population of screen-eligible adults and examined the all-cause healthcare utilization and costs by screening modality, described the healthcare utilization and costs associated with screening colonoscopy with and without polypectomy and described the frequency and costs of serious GI and other GI events following a colonoscopy. A secondary analysis examined the frequency and costs of cardiovascular events following a colonoscopy.

Methods

Study design and data source

This observational cohort study used administrative claims from the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (Commercial) and Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits (Medicare Supplemental) databases from January 1, 2004 to June 30, 2019. The Commercial database contains the inpatient, outpatient, and outpatient prescription drug experience of employees and their dependents, covered under a variety of fee-for-service and managed care health plans between 1995 and 2019. The Medicare Supplemental database contains the same healthcare data for retirees with Medicare Supplemental insurance paid for by employers between 1995 and 2019. Individuals in these databases may be dual enrolled in both the commercial and Medicare Supplemental insurance plans. The Medicare Supplemental database captures both the Medicare-covered portion of the payment (represented as Coordination of Benefits amount) and the employer-paid portion, and thus reflects the patient's full interaction with the healthcare system. All database records are statistically de-identified and certified to be fully compliant with US patient confidentiality requirements set forth in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Because this study used only de-identified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, this study was exempted by the institutions from Institutional Review Board approval.

All variables used to define study outcomes were obtained using medical codes such as the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM), the Current Procedural Terminology fourth edition (CPT-4), and the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS).

Patient selection

A cohort of adults at average risk of CRC was identified in the Marketscan Databases using the codes listed in Supplementary Table 1. Individuals were included if they had evidence of CRC screening during the selection window (January 1, 2014 through June 30, 2019). Qualifying CRC screening procedures included a colonoscopy, CT colonography, DCBE, FS, FIT, FOBT, and mt-sDNA. The date of their earliest claim for CRC screening during the selection window was defined as the index date. Included individuals were required to have evidence of only one CRC test type on the index date.

In the initial selection, individuals were required to be 45–75 years old on the index date and have continuous enrollment with medical and pharmacy benefits for ten years prior to the index date (pre-period). This pre-period was used to exclude individuals who were not due for screening along with those who were at increased risk of CRC. Individuals with evidence of not being due for screening included those with any claims for colonoscopy (screening or diagnostic) during the 10 years prior to the index date, any claims for FS, DCBE, or CT colonography in the five years prior to the index date, any claims for mt-sDNA during the three years prior to the index date, or any claims for FIT or FOBT during the year prior to the index date. Evidence of being at above-average risk for CRC included any claims indicating a family history of GI cancer or non-diagnostic claims with a diagnosis of colorectal polyps, colorectal neoplasm (benign or malignant), or inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease). In addition, individuals with at least one non-diagnostic claim with a diagnosis of blood in the stool in the three months preceding the index date were excluded. Diagnostic claims are claims for services often used in ruling out conditions and are not reliable for identifying individuals with a specific diagnosis. In an effort to retain a representative sample of adults at average risk for CRC, we did not exclude individuals with co-existing conditions, such as other types of cancer. The final analysis was restricted to individuals who were at least 50 years of age on the index date to focus the analysis on those who had CRC screening according to the 2016 USPSTF guidelinesCitation4.

Outcomes

Demographic characteristics were abstracted from the index date and included age, sex, geographic region of residence, index year, and payer (commercial or Medicare Supplemental). The proportion dual-enrolled in commercial and Medicare Supplemental insurance during the study period was not reported. The Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index (DCI) was measured using data from the 1 year immediately preceding the index date. The DCI is an aggregate measure of comorbidity expressed as a numeric score based on the presence of select diagnoses for chronic medical conditions, each with specific weights ranging from one to six points. The proportion of individuals with each DCI condition during this 1-year period was also reported.

CRC screening test utilization was reported by screening type: colonoscopy, FIT, FOBT, mt-sDNA, FS, CT colonography, and DCBE. Due to low sample sizes, the FS, CT colonography, and DCBE cohorts were excluded from further analysis. To understand the frequency of follow-up colonoscopy screening, the proportion with a colonoscopy in the 30 days following the initial CRC screening test was also reported.

The cost of the non-invasive CRC screening test (mt-sDNA, FIT, FOBT) was the cost on the claim for the CRC screening test and was reported among those with >$0 total costs on the claim. Screening colonoscopy is the most common CRC screening procedure and contributes to the overall cost of non-invasive CRC screening following a positive non-invasive screening test; therefore, the components of the costs associated with screening colonoscopy were reported in detail. Costs associated with a screening colonoscopy were examined in the 30 days prior to and following the initial colonoscopy and included colonoscopy, pathology, anesthesia, and prescription bowel preparation costs. Only individuals with at least 30 days of continuous enrollment following the index date (inclusive of the index date) were included in the colonoscopy cost analyses. The generic names of medications used to identify anesthesia and bowel preparation claims are listed in Supplementary Table 2. The costs of colonoscopy were stratified by those with and without polyp removal and were reported as total, health plan paid, and out of pocket. Results are reported for all individuals whose index screening event was a colonoscopy, segmented by the payer. A subanalysis was done on the portion of individuals with claims for pathology, anesthesia, and prescription bowel preparation, as this was hypothesized to be the highest cost subgroupCitation11.

We investigated events potentially associated with colonoscopy by identifying these events during the 30 days following the initial colonoscopy screening (inclusive of the index date). A diagnosis and its associated costs were only included in the analysis if the patient did not have the same diagnosis during the 12 months preceding the index date. Events and their associated costs were reported overall, by event type, and by individual event. Examined events included serious GI events (perforation and bleeding) and other GI events (paralytic ileus, nausea/vomiting/dehydration, and abdominal pain). A secondary analysis examined cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction/angina, arrhythmia, heart failure, cardiac/respiratory arrest, syncope/hypotension/shock, stroke, and transient ischemic attack).

The costs associated with events following colonoscopy were measured in two ways. First, we measured the costs captured on claims with a diagnosis of the event of interest or the costs captured on pharmacy claims for the therapeutic class related to the event of interest in the 30 days following the initial colonoscopy screening among individuals with the event. The generic names of medications used to identify pharmacy claims are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Second, we measured the all-cause total costs in the 30 days following the initial colonoscopy screening among individuals with the event and included the cost of the colonoscopy procedure. Event-related and all-cause total costs were reported overall and by the event. The costs of events following colonoscopy were stratified by those with and without polyp removal and segmented by the payer.

Healthcare costs were based on paid amounts of adjudicated claims, including insurer and health plan payments, as well as patient cost-sharing in the form of copayment, deductible, and coinsurance. The costs for services provided under capitated arrangements were estimated using payment proxies based on paid claims at the procedure level using the MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases. All dollar estimates were inflated by the Medical Care Component of the Consumer Price Index for 2019Citation12.

Statistical analysis

This was a descriptive analysis of the costs associated with CRC screening, focusing on the costs associated with colonoscopy, and the frequency and costs of events potentially related to colonoscopy. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were reported for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Medians were also reported for cost variables. Tests of statistical significance were used to compare the cost of non-invasive CRC screening and to compare the cost of individuals with colonoscopy versus without polypectomy. For these comparisons, statistical significance was determined using Student's t-tests for continuous variables and using Chi-square tests for categorical variables. The alpha level for all statistical tests was 0.05; however, statistical significance should be interpreted in the context of large sample sizes. All data analyses were conducted using WPS version 4.2 (World Programming, United Kingdom).

Results

Patient characteristics

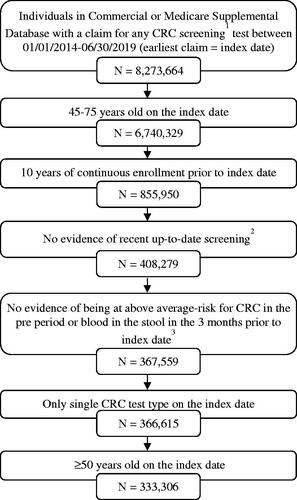

We identified 333,306 average-risk adults with CRC screening eligible for study inclusion (). The population of screened individuals had a mean (SD) age of 57.0 (6.1) years, and 53.0% were female (). The majority of screened individuals had commercial insurance (89.9%) on the index date, and 10.1% had Medicare Supplemental insurance. The mean (SD) DCI was 0.5 (1.2), and the most common DCI comorbid conditions were diabetes (13.2%) and chronic pulmonary disease (8.5%).

Figure 1. Cohort selection. 1CRC screening tests were mt-sDNA, colonoscopy, fecal immunochemical testing (FIT), fecal occult blood testing (FOBT), flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS), CT colonography and double-contrast barium enema (DCBE). 2FIT or FOBT in the year prior to the index date, no evidence of mt-sDNA test in 3 years prior to the index date, no evidence of other screening (FS, CT colonography or DCBE) in 5 years prior to the index date, and no evidence of colonoscopy in 10 years prior to the index date. 3Codes and conditions for identifying above-average risk adults can be found in supplementary files.

Table 1. Patient characteristics of average-risk adults with CRC screening.

Colonoscopy was the most common CRC screening procedure (70.6%), followed by FIT (17.7%), FOBT (8.1%), and mt-sDNA (3.2%). CT colonography, DCBE, and FS were used in less than 1% of screened individuals ().

Cost of non-invasive CRC screening

The mean (SD) total cost of mt-sDNA was $524 ($109), while the mean (SD) total cost of FIT and FOBT screening was $24 ($21) and $6 ($10), respectively (). Colonoscopy after a non-invasive CRC screening test may have contributed additional costs in these cohorts. Overall, 1.9% of individuals with mt-sDNA, 3.7% of those with FIT, and 5.2% of those with FOBT had a follow-up colonoscopy in the 30 days following the initial CRC screening ().

Table 2. Utilization and costs associated with CRC screening among average-risk adults.

Cost of screening colonoscopy and colonoscopy-related utilization

Among average-risk adults screened by colonoscopy with at least 30 days post-screening continuous enrollment (N = 228,409), 47.6% had a bowel preparation prescription within 30 days before or after the colonoscopy, 82.9% had an anesthesia claim, and 60.4% had a pathology claim (). Among individuals with colonoscopy, 57.3% had a polypectomy, and while the use of prescription bowel preparations (48.5% vs 46.3%) and anesthesia (83.0% vs 82.9%) was similar between individuals with or without polypectomy, the use of pathology services was much more common among individuals with polypectomy (96.9% vs 11.5%).

Table 3. Utilization and costs associated with colonoscopy in the 30 days prior to and following colonoscopy among average-risk adults (N = 228,409).

The mean (SD) cost of a colonoscopy was $2,125 ($1,369) for the colonoscopy procedure alone (). Mean colonoscopy costs increased to $2,543 ($1,575) among the 55,183 individuals who had claims for anesthesia, pathology, and bowel preparation, of which $120 ($282) were out-of-pocket costs. The mean cost of a colonoscopy was $604 higher for individuals with polypectomy compared to those without ($2,383 [$1,515] vs $1,779 [$1,049]). In addition, the cost of colonoscopy was higher for adults with commercial insurance compared to those with Medicare Supplemental insurance ($2,200 [$1,336] vs $1,486 [$1,474]) (Supplementary Table 3).

Events and costs following colonoscopy

Serious GI events, such as GI bleeding and perforation, were observed in 1.3% of those with colonoscopy, while 1.9% had other GI events (). The most common other GI event was abdominal pain, which occurred in 1.4% of individuals (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 4. Events following colonoscopy and costs associated with eventsa in the 30 days following colonoscopy among average-risk adults.

Mean (SD) event-related costs in the 30 days following a colonoscopy screening were $2,631 ($7,145) among individuals with a serious GI event and $1,774 ($5,470) among individuals with any other GI event (). Mean (SD) all-cause total costs in the 30 days following a colonoscopy screening, inclusive of the colonoscopy procedure, were $8,003 ($15,038) among individuals with a serious GI event and $9,497 ($18,120) among individuals with any other GI event (). The costliest GI events were perforations (event-related: $18,203 [$27,763]; all-cause: $38,806 [$39,113]); and paralytic ileus (event-related: $15,009 [$24,228]; all-cause: $36,000 [$48,092]) (Supplementary Table 4).

Serious GI events occurred more often in individuals with Medicare Supplemental insurance compared to those with commercial insurance (4.5% vs 1.0%), while other GI events occurred in 3.0% of individuals with Medicare Supplemental insurance but only 1.8% of those with commercial insurance (). However, the mean (SD) event-related costs in the 30 days following colonoscopy among individuals with a serious GI event were $3,201 ($8,444) for those with commercial insurance compared to $1,583 ($3,491) for those with Medicare Supplemental insurance. Mean (SD) all-cause total costs in the 30 days following a colonoscopy screening among individuals with a serious GI event were $8,987 ($16,376) for those with commercial insurance compared to $6,193 ($12,003) for those with Medicare Supplemental insurance.

For all individuals screened by colonoscopy, serious GI events occurred more often in those with polyp removal compared to those without polyp removal (Supplementary Table 4). Mean (SD) event-related costs associated with serious GI events were significantly higher among individuals with polyp removal compared to those without polyp removal (event-related: $2,958 [$7,432] vs $2,006 [$6,521], p < .001; commercial: $3,626 [$8,770] vs $2,417 [$7,753], p = .002; Medicare Supplemental: $1,772 [$3,814] vs $1,199 [$2,683], p = .011). Similar trends were observed with all-cause total costs.

In a secondary analysis of cardiovascular events in the 30 days following the screening, 1.2% of screened individuals had an incident cardiovascular event. Event-related and all-cause total costs of cardiovascular events following colonoscopy averaged $4,234 ($17,877) and $13,677 ($28,407), respectively, with stroke being the most costly (event-related: $10,713 [$42,975]; all-cause: $22,511 [$47,960]). The rates and costs of individual events can be found in Supplementary Table 4. Overall, GI or cardiovascular events following colonoscopy were relatively uncommon and observed in approximately 4.1% of the 228,409 individuals screened by colonoscopy ().

Discussion

In this large, claims-based analysis of CRC screening costs, the mean cost of colonoscopy was $2,200 for average-risk adults with commercial insurance compared to $1,486 among those with Medicare Supplemental insurance. GI and cardiovascular events following colonoscopies were infrequent but resulted in higher costs among impacted individuals. Our estimates are derived from robust analyses of data from a nationally representative sample and provide updated costs for CRC screening procedures and events following colonoscopy. These findings can inform decision-making and contemporary modeling of the economic considerations related to CRC screening. Moreover, some of the reported information may be useful in counseling patients on surprise charges, such as those for pathology and anesthesia, or the frequency of GI and cardiovascular events following colonoscopy.

The costs of colonoscopy were previously examined by Pyenson et al. using 2010 data from the MarketScan Commercial database and the Medicare 5% beneficiary sampleCitation8. In that study, the mean cost of a screening colonoscopy was $2,146 for adults with commercial insurance and $1,071 for adults with Medicare insurance. Notably, the out-of-pocket portion of costs reported by Pyenson et al. averaged $334 for adults with commercial insurance and $275 for adults with Medicare insurance compared to $79 and $81 dollars in this study. This difference is likely due to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, which has been associated with a reduction in out-of-pocket costs for both screening and therapeutic colonoscopiesCitation13. However, a recent study by Scheiman et al. reported that roughly 12% of commercially-insured adults who underwent elective colonoscopies with in-network endoscopists and facilities received surprise out-of-network claims from ancillary providers such as pathologists or anesthesiologistsCitation8. While the median out-of-pocket costs for all patients was $0, they estimated the median potential surprise out-of-pocket costs to be $418 dollars for patients with out-of-network claims. Consistent with this study, both Pyenson et al. and Scheiman et al. reported higher plan-paid and patient-paid costs for colonoscopy with the intervention compared to colonoscopy without interventionCitation8,Citation11.

The 30-day all-cause total costs of individuals with rare, serious GI events after colonoscopy (including colonoscopy procedure costs) averaged $8,003 and ran as high as $38,806 for GI perforation. Prior studies have reported 30-day event rates after screening colonoscopy of 0.24%–0.47% for serious GI events, 0.38%–0.58% for non-serious GI events, and 0.73%–0.99% for cardiac eventsCitation6,Citation14. By comparison, this study reports serious reported 30-day event rates of 1.3% for serious GI events, 1.9% for non-serious GI events, and 1.2% for cardiac events. The higher rates of events observed in this study may be due to variations in the codes sets used to identify events, differences in patient cohorts, and the inclusion of office visit data, which was not available to Wang et al. Importantly, the rates of the high-cost events, GI perforations (0.04%) and stroke (0.05%), were similar to the rates reported in the literatureCitation6,Citation7,Citation15, as was the rate of paralytic ileus in the Medicare population (0.07%)Citation16. The higher rates of events observed in the Medicare population compared to the commercial population is consistent with prior analysis showing that event rates increase with patient ageCitation16.

This study used a robust code set and large sample size to provide updated estimates of the costs associated with common colonoscopy screening procedures with a focus on colonoscopy. Costs are reported for average-risk adults with commercial insurance or Medicare Supplemental insurance going in for a standard screening procedure. Cost drivers for colonoscopy, such as the presence of polypectomy and events following colonoscopy were reported to facilitate the modeling of screening strategies. Indirect cost drivers, such as the cost of time off from work for individuals and caregivers, were not included in this analysis; however, indirect costs are an important component of the cost of colonoscopy and warrant inclusion in a comprehensive assessment of colonoscopy screening costs.

When examining events following colonoscopy, our analysis examined a wide range of GI and cardiovascular conditions that had been reported in the literature previously. Citation6,Citation7,Citation16 Some events like GI bleeding and perforation are commonly associated complications of colonoscopyCitation7, while others are only weakly associated with colonoscopy and may be independently occurring morbidities. In particular, the literature around cardiovascular events is conflicting,Citation6,Citation16 but cardiovascular events were included in this analysis because these events were reported to be rare but clinically relevantCitation6. As this study only examined events following colonoscopy and did not include a control group, we cannot infer what proportion, if any, of the events observed are potential complications of the procedure. Future work could address this gap by comparing event rates after different screening modalities while adjusting for systemic differences in the types of patients who utilize each modality.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, GI and cardiovascular events newly occurring within 30 days of the colonoscopy procedure were identified on inpatient and outpatient claims in any diagnosis position on the medical claim. We assumed these events were potentially related to the colonoscopy; however, it is possible that some of these events, particularly those events identified in the outpatient setting, maybe randomly occurring proximate events. The inclusion of these proximate events may have resulted in an overestimate of the true rate of GI and cardiovascular events following colonoscopy.

Second, our two estimates of the cost of an event following colonoscopy (i.e. event-related and all-cause costs) are likely an underestimate and an overestimate of the true cost of these events. The estimate which only included claims with a diagnosis of the event is an underestimate of the true cost as it does not include the cost of all outpatient prescriptions or the cost of claims which would have been less costly or not present had the event not occurred but which for a variety of reasons did not include the specific diagnosis in the claims record. The all-cause estimate is likely to be an overestimate of the true cost because it includes claims for services unrelated to the event such as the index colonoscopy. However, both estimates may underestimate true cost because some events following colonoscopy may not resolve within 30 days, while others may result in patient death and exclusion from our analysis due to the requirement of at least 30 days of continuous enrollment following colonoscopy.

Third, this analysis does not capture the cost of over-the-counter medications, such as those for commonly used non-prescription bowel preparation options. Fourth, there is potential for misclassification of covariates or study outcomes as individuals were identified through administrative claims data, which are subject to data coding limitations and data entry errors. Fifth, this study was limited to only those individuals with commercial health coverage or private Medicare supplemental coverage. Consequently, the results of this analysis may not be generalizable to individuals with Medicare without supplemental coverage, other insurance types, or without health insurance coverage.

Conclusions

This study provides updated and more detailed information regarding the costs of colonoscopy based on a comprehensive review of a robust administrative claims dataset. The findings from a large, nationally representative sample of individuals with commercial or Medicare Supplemental insurance will better inform analyses and assessments of endorsed CRC screening options.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Exact Sciences Corporation.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

NP and KW are employed by IBM Watson Health, which received funding from Exact Sciences Corporation to conduct this study. DAF was an employee of Duke University at the time the study was conducted but is currently an employee of Eli Lilly and Company; she was previously a consultant for Exact Sciences and Guardant Health and a site investigator for Freenome. LM is an employee of Exact Sciences Corporation. PL serves as Chief Medical Officer for Screening at Exact Sciences through a contracted services agreement with Mayo Clinic. PL and Mayo Clinic have contractual rights to receive royalties through this agreement. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in study design, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting and revising the paper and approving the final version of the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics approval and informed consent

All database records are statistically de-identified and certified to be fully compliant with US patient confidentiality requirements set forth in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Because this study used only de-identified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, this study was exempted from Institutional Review Board approval.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (110.5 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical Writing services were provided Jessamine Winer-Jones, PhD of IBM Watson Health. Programming services were provided by Steven Gelwicks of IBM Watson Health. Analytic services were provided by Kathryn DeYoung of IBM Watson Health at the time the analysis was conducted. Statistical services were provided by David Smith, PhD of IBM Watson Health. These services were paid for by Exact Sciences

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from IBM Watson Health. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA A Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30.

- Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O'Brien MJ, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(8):687–696.

- Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1106–1114.

- U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(23):2564–2575.

- Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(4):250–281.

- Wang L, Mannalithara A, Singh G, et al. Low rates of gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal complications for screening or surveillance colonoscopies in a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(3):540–555. e8.

- Reumkens A, Rondagh EJA, Bakker MC, et al. Post-colonoscopy complications: a systematic review, time trends, and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(8):1092–1101.

- Pyenson B, Scammell C, Broulette J. Costs and repeat rates associated with colonoscopy observed in medical claims for commercial and Medicare populations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):92.

- Adler A, Geiger S, Keil A, et al. Improving compliance to colorectal cancer screening using blood and stool based tests in patients refusing screening colonoscopy in Germany. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14(1):183.

- Simon K. Colorectal cancer development and advances in screening. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:967–976.

- Scheiman JM, Fendrick AM, Nuliyalu U, et al. Surprise billing for colonoscopy: the scope of the problem. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(3):426–428.

- Consumer Price Index details report tables [cited 2020 1 October]. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/home.htm

- Hamman MK, Kapinos KA. Affordable care act provision lowered out-of-pocket cost and increased colonoscopy rates among men in Medicare. Health Affairs. 2015;34(12):2069–2076.

- Andersen SW, Blot WJ, Lipworth L, et al. Association of race and socioeconomic status with colorectal cancer screening, colorectal cancer risk, and mortality in Southern US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1917995-e.

- Kothari ST, Huang RJ, Shaukat A, et al. ASGE review of adverse events in colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(6):863–876.e33.

- Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Mariotto AB, et al. Adverse events after outpatient colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(12):849–857.