Abstract

Acute pain is among the most common reasons that people consult primary care physicians, who must weigh benefits versus risks of analgesics use for each patient. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is a first-choice analgesic for many adults with mild to moderate acute pain, is generally well tolerated at recommended doses (≤4 g/day) in healthy adults and may be preferable to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that are associated with undesirable gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular effects. Although paracetamol is widely used, many patients and physicians still have questions about its suitability and dosing, especially for older people or adults with underlying comorbidities, for whom there are limited clinical data or evidence-based guidelines. Inappropriate use may increase the risks of both overdosing and inadequate analgesia. To address knowledge deficits and augment existing guidance in salient areas of uncertainty, we have researched, reviewed, and collated published evidence and expert opinion relevant to the acute use of paracetamol by adults with liver, kidney, or cardiovascular diseases, gastrointestinal disorders, asthma, or/and who are older. A concern is hepatotoxicity, but this is rare among adults who use paracetamol as directed, including people with cirrhotic liver disease. Putative epidemiologic associations of paracetamol use with kidney or cardiovascular disease, hypertension, gastrointestinal disorders, and asthma largely reflect confounding biases and are of doubtful relevance to short-term use (<14 days). Paracetamol is a suitable first-line analgesic for mild to moderate acute pain in many adults with liver, kidney or cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disorders, asthma, and/or who are older. No evidence supports routine dose reduction for older people. Rather, dosing for adults who are older and/or have decompensated cirrhosis, advanced kidney failure, or analgesic-induced asthma that is known to be cross-sensitive to paracetamol, should be individualized in consultation with their physician, who may recommend a lower effective dose appropriate to the circumstances.

Introduction

People worldwide use paracetamol (acetaminophen) more than any other analgesicCitation1–3; besides being readily available over-the-counter (OTC), its popularity rests on being generally well tolerated and considered safer than other analgesics when taken as directed, especially in high-risk users such as older people or adults with comorbiditiesCitation1–6. Accordingly, international guidelines and medical experts consistently recommend paracetamol for first-line treatment of acute mild/moderate painCitation6–8.

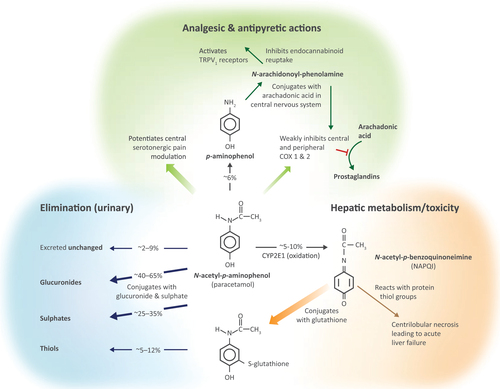

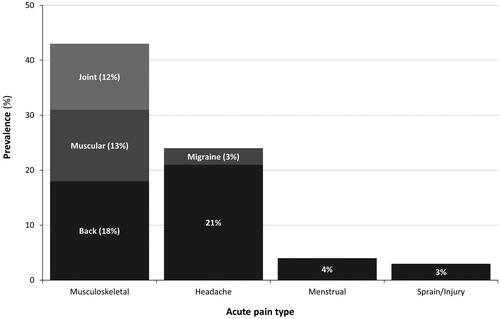

Paracetamol has antipyretic and analgesic effects (), with complex mechanisms that distinguish it from non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioidsCitation1,Citation2,Citation6,Citation9. Its most common everyday uses in adults include headaches, and musculoskeletal, or menstrual painCitation7; musculoskeletal pain and sprains/injury account for 45% of pain episodes for which adults may use OTC or prescription analgesics ()Citation10. The standard adult dose of paracetamol is 0.5–1.0 g, taken as needed at least 4–6 h apart, to a maximum of 4 g/day; it is recommended to use the lowest dose that relieves symptoms, taken for the shortest possible treatment durationCitation8,Citation11,Footnotei.

Figure 1. Paracetamol (N-acetyl-p-aminophenol) pharmacotherapeutic mechanisms, metabolism, and toxicity. Abbreviations. TRPV, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V; CYP2E1, cytochrome P450 2E1; COX, cyclooxygenase.

Figure 2. Pain episodes from 6527 diary entries by adults aged 18–65 years. Data source: Hersch et al.Citation10.

Paracetamol very rarely has adverse effects in healthy adults who take ≤4 g/day in episodic useCitation2,Citation12,Footnoteii and as directed by the label, but doses exceeding the recommended daily maximum may be harmful due to the accumulation of a toxic metabolite, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI), that can cause liver failure ()Citation2,Citation4,Citation12. Although some epidemiological studies have also implied that paracetamol use may contribute to kidney or cardiovascular disease (CVD), gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, and asthma, especially among chronic users, these findings remain inconclusive and of unproven relevance to episodic acute useCitation2,Citation4,Citation13,Citation14. Nevertheless, such observations have raised questions about the suitability of paracetamol for people with underlying comorbidities or who are elderly, and whether dose reduction might be appropriate in certain circumstancesCitation4,Citation14–16.

Such concerns compound widespread lack of awareness, especially among older people, which conduces to inappropriate use that may increase the likelihoods of both accidental overdose and inadequate pain managementCitation3,Citation5,Citation17,Citation18. Many overdoses are unintentional, because people do not know the recommended maximum dose or are unaware of the presence or amount of paracetamol as an ingredient of numerous OTC medicationsCitation2,Citation7,Citation17. On the other hand, some adults take doses lower than are recommendedCitation8 and inadequate pain relief may lead them to use stronger analgesics with well-documented side effectsCitation5,Citation12.

Acute pain is one of the most common reasons that people use primary care servicesCitation7,Citation10 and despite available consumer information, many still have questions about paracetamol, especially regarding its safety and dosing for people with specific health concernsCitation3. In a survey of adults with liver disease, 60.5% said they would ask a physician before choosing an OTC analgesic containing paracetamolCitation17. Physicians recommending any analgesic must be confident that its benefit will outweigh potential harmsCitation2,Citation7,Citation14. This necessitates thorough appraisal of each patient’s circumstances, based on which they can be advised which treatment options may be suitable, and on what dose to take. Healthcare professionals should be best placed to do this but may themselves be uncertain about the appropriate use of paracetamol, especially for patients with special health concerns, for whom there are limited clinical data or specific dosing instructionsCitation3,Citation5,Citation16,Citation17. Pertinently, patient information cautions people with liver or kidney disease, or who have aspirin-sensitive asthma, to consult their physician before using paracetamol, but does not specify whether or how dosing should be adjustedCitation11,Citation19.

To address knowledge gaps and augment existing guidance, we have reviewed published evidence and expert opinion pertaining to the acute use of paracetamol by adults with liver or kidney disease, CVD, GI disorders, asthma, or who are older. Briefly, independent researchers shortlisted articles retrieved from PubMed searches that combined the terms “paracetamol” or “acetaminophen” with others chosen to retrieve articles relevant to each of the aforementioned areas of potential health concern, which the authors had prespecified. The authors checked that selected articles were within the scope of their review and suggested others based on their specialist knowledge. Reference lists of reviewed articles were perused to identify additional sources. Although this review discusses the use of GlaxoSmithKline products in this context, the authors strove to remain impartial and produce an objective, evidence-based summary that reflects the current consensus of scientific expertise in these areas. We encourage physicians and other healthcare professionals to use this resource to help people make informed choices about pain management.

Liver disease and hepatotoxicity

Many patients and physicians do not know whether paracetamol is suitable for people with liver disease – potential hepatotoxicity is a particular concernCitation17,Citation20–22. Paracetamol is almost entirely metabolized by the liver (): ∼80% is eliminated as inactive glucuronide (40–65%) and sulphate (25–35%) conjugates but 5–10% is oxidized by cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) to generate NAPQI, a highly reactive intermediate that is normally rapidly neutralized by conjugation with glutathione, which is constantly replenishedCitation4,Citation12,Citation22–24. However, if NAPQI accumulates faster than it is detoxified (e.g. due to paracetamol overdose or, hypothetically, in glutathione-depleted states) it can cause acute necrotic liver failureCitation4,Citation6,Citation23,Citation24. Theoretically, pathologies that affect this pathway could increase the risk of paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicityCitation25,Citation26; for example, hyperglycemia and starvation induce CYP2E1 activityCitation27, and malnutrition may deplete hepatic glutathione, potentially abating NAPQI detoxificationCitation23,Citation25. Expert reviewers, however, maintain that paracetamol at therapeutic doses generates insufficient NAPQI to exhaust glutathione, and that there is no convincing clinical evidence that malnourished individuals who use paracetamol as directed are at increased risk of hepatotoxicityCitation23,Citation25. Despite the lack of good-quality evidence, some precautionary guidance nevertheless suggests that people weighing <50 kg should take paracetamol at lower doses (contrary to the drug label)Citation25. Studies on how diabetes influences paracetamol metabolism found limited effects on its conjugation and clearance pathways and there has been no suggestion that people with diabetes should use a lower doseCitation28,Citation29.

Perceived risk of hepatotoxicity may lead patients and physicians either to believe incorrectly that paracetamol is absolutely contraindicated in liver disease and opt for other drugs that may be less appropriate (e.g. NSAIDs), or use too low a dose to relieve pain satisfactorilyCitation12,Citation17,Citation20–22. The challenges of pain management in patients with liver disease are compounded by the dearth of prospective studies of analgesic pharmacology and safety in this population and lack of specific evidence-based dosing recommendations. As a result, prescribing and usage practices vary considerably and pain may be undertreatedCitation12,Citation17,Citation19–22.

Reappraisal of reported paracetamol poisoning cases has suggested that acute hepatotoxicity is much rarer when used as its label recommends than was commonly supposedCitation4; in retrospect, many purported cases can actually be attributed to unrecognized overdosing, which is mostly unintentional and often occurs in the context of alcoholismCitation4,Citation12,Citation20,Citation24,Citation30,Citation31. Nonetheless, there has been conjecture as to whether hepatotoxicity at therapeutic doses of paracetamol might be more likely in people with liver diseaseCitation12,Citation20,Citation22,Citation32, especially chronic alcoholics, who may have depleted glutathione reserves and potentiated oxidation to NAPQICitation4,Citation12,Citation20,Citation22,Citation23. Relevant research over 40 years has consistently shown negligible risk of hepatotoxicity from short-term use of paracetamol at standard doses up to 4 g/day by patients with liver disease, including moderate to heavy drinkers ()Citation12,Citation21–23,Citation32–35. Although patients with severe liver disease who took single doses of either 1 g or 1.5 g paracetamol had a longer plasma half-life versus controls, there was no evidence of impaired glutathione conjugation or clinical hepatotoxicity, nor of drug accumulation after taking 3 g/day for 5 daysCitation33,Citation36. Likewise, there were neither accumulation nor evidence of hepatotoxicity in patients with stable chronic liver disease who took 4 g/day paracetamol for 5 days consecutively, and no clinically significant changes after 13 days continuous useCitation32. In patients with cirrhosis, including recent alcohol users, episodic doses of ≤3 g/day paracetamol during the previous month were not associated with acute hepatic decompensation (ascites, variceal bleeds, encephalopathy, jaundice)Citation37. In other studies, there was no evident liver damage in newly abstinent chronic alcoholics who took 4 g/day paracetamol for 3 daysCitation35, or in moderate drinkers who took 4 g/day for 10 daysCitation34.

Table 1. Effects of short-term use of standard oral doses of paracetamol in adults who have liver disease, including alcoholic cirrhosis.

Collectively, these findings constitute persuasive evidence that short-term use (<1–2 weeks) of up to 4 g/day paracetamol is an appropriate treatment for mild to moderate pain in patients with cirrhotic liver disease, even moderate to heavy drinkersCitation12,Citation20,Citation22,Citation38. No high-quality evidence supports reducing the maximum recommended dose of paracetamol (4 g/day) for short-term use by patients with compensated cirrhosisCitation19. It is difficult to make dosing recommendations for people with decompensated alcoholic liver disease due to insufficient data on this group − 3–4 g/day short-term for acute pain may be reasonableCitation12. Experts also concur that 2–3 g/day may be more prudent if used by alcoholics for more than 14 days, without significantly compromising analgesiaCitation12,Citation19–22,Citation38.

The potential risks and benefits of paracetamol for patients with liver disease must be weighed against those of alternative treatment options, such as NSAIDs or opioidsCitation4,Citation21,Citation23. Given its established safety profile and lack of sedating or nephrotoxic effects, paracetamol is the analgesic of choice irrespective of liver disease etiology, whereas NSAIDs are best avoided due to increased risk of GI bleeding, renal failure, and antiplatelet effectsCitation4,Citation12,Citation17,Citation21,Citation22,Citation38.

Cardiovascular disorders

People with CVD or cardiovascular (CV) risk factors account for a significant proportion of the primary care caseloadCitation39,Citation40. To relieve musculoskeletal pain in such patients, the American Heart Association has advocated stepwise escalation that starts by using analgesics with the least associated risk of adverse CV effects, usually paracetamol or aspirin at the lowest effective dose, and suggested paracetamol initially for people at risk of GI bleedingCitation41. If first-line treatment is ineffective or poorly tolerated, a non-selective NSAID or cyclo-oxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitor may be considered but should be used cautiously, due to increased risks of serious CV or GI complicationsCitation39,Citation41–44. Contrastingly, there is no conclusive evidence associating paracetamol with increased risk of CV events in patients with or at risk of CVDCitation39,Citation42,Citation45. Many patients with CV comorbidities require polypharmacy, which substantially increases the likelihood of drug-drug interactions; using paracetamol instead of NSAIDs has been recommended to avoid potential interactions that may warrant avoiding a combination or modifying therapyCitation40. Accordingly, CVD patients worldwide often use paracetamol for pain reliefCitation43,Citation46.

The pharmacology of paracetamol differs from NSAIDs and has only recently become better understoodCitation2,Citation6,Citation9. Given such widespread use, even slightly increased risk to potentially vulnerable patients would raise concernCitation13,Citation45,Citation47; however, studies of CV-related outcomes in paracetamol users have produced inconsistent resultsCitation43,Citation48. In particular, there are insufficient high-quality data to assess hypothetical CV risks associated with paracetamol in typical episodic useCitation49. Further studies, especially randomized controlled trials (RCTs), may help to resolve remaining uncertaintiesCitation43,Citation45,Citation49.

Hypertension

Although some observational studies have associated paracetamol use with elevated blood pressure (BP)Citation14, there is inconclusive evidence of clinically significant hypertensive effects from episodic acute useCitation49,Citation50. Reported epidemiological associations between chronic/frequent paracetamol use and incident hypertensionCitation51–53, may be attributable in part to confounding factorsCitation49; for example, the more often people are prescribed analgesics by a physician, the likelier they are to have their BP measured and to have hypertension diagnosedCitation13. Other investigators have found no association between paracetamol and hypertensionCitation54,Citation55. A retrospective cohort of adults with hypertension who were first prescribed NSAIDs had a 2 mmHg increase in systolic BP at 1-year follow-up relative to new paracetamol users, who were matched by propensity scores for baseline BP, age, and cardiometabolic comorbiditiesCitation56. Besides clearly increasing BP and the risk of serious CV events in both normotensive and hypertensive individuals, NSAIDs directly interfere with the actions of many antihypertensive and diuretic agents, whereas paracetamol does not appear toCitation39,Citation42,Citation49,Citation52,Citation57; reassuringly, there is no signal that hypertensive paracetamol users have increased risks of myocardial infarction or strokeCitation45, which have been associated with BP elevation by just a few mmHg during follow-up studiesCitation39,Citation49. In this context, it is noteworthy that the sodium salts in soluble paracetamol products can significantly raise BPCitation58,Citation59, which may partly explain apparent associations between paracetamol use and hypertensionCitation60; healthcare professionals should advise hypertensive patients to use sodium-free formulationsCitation59.

Small prospective RCTs have also investigated whether paracetamol affects BPCitation14,Citation49. The earliest found a 4 mmHg rise in systolic BP in 20 hypertensive patients who took 3 g paracetamol per day (two 500 mg tablets, 8-hourly for 4 weeks)Citation61. However, subsequent RCTs found no significant BP changes in people with mild/moderate hypertensionCitation57,Citation62,Citation63. In another RCT, 33 patients with coronary heart disease who took 1 g paracetamol thrice-daily for 2 weeks had significantly increased ambulatory BP, which raised concern about using paracetamol in such patientsCitation49,Citation64; however, the validity and clinical relevance of this study have been challengedCitation47. To augment this limited and conflicting evidence, a recent British RCT investigated the effect of giving 110 people with hypertension paracetamol 1 g four times per day for 14 consecutive days, typifying the dosing schedule used to treat chronic painCitation65. Uninterrupted use of 4 g/day paracetamol increased systolic BP by 4.7 mmHg versus placebo, suggesting that regular long-term use of paracetamol may be inadvisable for people with risk factors for CVDCitation65; notably, however, the authors saw no grounds for such concern about short-term episodic use in this settingCitation66.

CV endpoints

The CV safety of widely used analgesics has become a major public health concern, especially given evidence accrued since 2011 that NSAIDs which are still often used by patients with CVD have no risk-neutral treatment window; even at low doses for <7 days, non-aspirin NSAIDs have been associated with increased risk of thrombotic CV eventsCitation44. A Swedish national study found heart failure to be associated with NSAIDs but not paracetamolCitation67. Among 70,971 United States (US) female nurses without known CVD, occasional paracetamol use (1–21 days/month) was not associated with increased CV risk; although women who took paracetamol frequently (≥22 days/month) were increasingly likely to have CV events compared with non-users, with greatest risk at ≥15 tablets/weekCitation48, the analytic methodology has been criticizedCitation13. A 2016 meta-analysis also reported a dose-response relationship between paracetamol and adverse CV eventsCitation15 but its findings too have been disputed, particularly concerning inadequate treatment of potential biasesCitation13,Citation68. A 10-year follow-up study of 10,878 British hypertensive patients found no relationship between paracetamol use or exposure and the risk of any CV event or strokeCitation45. In a recent cohort of frail nursing home residents with multimorbidity and polypharmacy, neither paracetamol use nor dosing affected CV mortality, although participants with diabetes had increased stroke riskCitation69.

Available evidence does not indicate that episodic use of paracetamol at recommended doses is associated with any additional risk of major CV eventsCitation43,Citation45; it can therefore be considered the first-choice analgesic for mild to moderate acute pain in most people with CV risk factors, especially those liable to NSAID-related GI bleedingCitation6,Citation39,Citation41.

Gastrointestinal disorders

Paracetamol is generally accepted to have excellent GI tolerability and is consequently an analgesic of choice for patients at risk for adverse GI eventsCitation4,Citation6,Citation70. Unlike aspirin and some other NSAIDs that reportedly increase the risk of GI bleeding at any doseCitation71, paracetamol appears to have negligible risk of causing or exacerbating GI ulcers or related complicationsCitation6,Citation70. Prospective studies have shown that paracetamol does not damage the GI tractCitation4, and a meta-analysis found no significant effect of paracetamol at any dose on upper GI bleedingCitation72. Epidemiological studies of health records have produced conflicting results; although some found no association between paracetamol use and GI bleedingCitation70, others have suggested that the incidence of adverse GI reactions may increase dose-dependentlyCitation73–75. However, these positive associations must be interpreted cautiously, as they could reflect inherent biases and confounding factors that may invalidate inferences about causality. A likely explanation is that physicians recommend paracetamol preferentially over NSAIDs to patients at high risk for gastropathy because they consider paracetamol to be safer (confounding by indication), while widespread use of paracetamol means it is often the first-line treatment for GI pain due to a pre-existing condition (protopathic bias)Citation4,Citation70. For example, observations that paracetamol users sometimes experience dyspepsiaCitation75 probably reflect that paracetamol is the preferred analgesic for patients with GI risk factorsCitation70. A recent analysis of the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report (JADER) pharmacovigilance database affirmed that paracetamol causes less GI injury than NSAIDsCitation1.

Based on evidence that paracetamol lacks major GI toxicity in short-term use and has GI safety superior to that of many NSAIDsCitation1,Citation4,Citation6,Citation70, paracetamol can be recommended as a first-line treatment for mild to moderate acute pain in patients at risk of GI ulceration or bleedingCitation6,Citation70.

Nevertheless, it is important for physicians to be aware of how GI disorders such as gastric dysmotility, which is a common complication of type 2 diabetesCitation76, GI ulcers, or other conditions, may affect the absorption and/or pharmacokinetics of paracetamolCitation77. Absorption of orally administered paracetamol depends on its dissolution in the stomach and the gastric emptying rateCitation78. A rapid-dissolving oral paracetamol formulation that enables faster absorption with less inter/intra user variability, may be more suitable than standard paracetamol tablets for people with delayed gastric emptyingCitation79,Citation80. Sixteen patients with gastric or duodenal ulcers had prolonged and increased absorption of 1 g paracetamol relative to healthy controls and slower clearance, particularly among those with duodenal ulceration, suggesting that reduced paracetamol dosing may be appropriateCitation81; however, larger studies would be needed to corroborate this provisional evidence. Conversely, people with ulcerative colitis had no difference versus healthy controls in the clearance of 1 g peroral paracetamol or its metabolitesCitation82, which would support these patients using a standard dose. The jejunum is the major site of paracetamol absorption, and people with short bowels are likely to have impaired uptake of oral dosesCitation77; a rectal paracetamol suppository may be administered in such cases but will have slower, less complete absorption and a less predictable effect compared with an oral doseCitation2,Citation6,Citation77.

Kidney disease

Many people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) need pain relief; some 40–60% of those receiving dialysis and 60–70% or more with advanced/end-stage renal disease are reported to suffer pain, predominantly musculoskeletalCitation83,Citation84. However, high-quality evidence in this setting is limited, and diverse prescription practices suggest uncertainty as to the most expedient pharmacotherapeutic approachCitation85. Consequently, pain management is suboptimal in many such patients, which diminishes their quality of life and imposes additional healthcare burdensCitation83,Citation86.

There has been speculation that paracetamol may be associated with renal impairmentCitation87,Citation88. Historically, realization that classic analgesic nephropathy was caused by phenacetin overuse raised concerns that paracetamol, its primary metabolite, might have similar injurious renal effectsCitation88,Citation89; however, this hypothesis has been dismissedCitation88–91. Although acute nephrotoxicity has been documented in rodents given paracetamol doses of ≥500 mg/kg and following overdoses in a few clinical casesCitation87,Citation90,Citation91, there is no evidence that episodic use of paracetamol alone at recommended doses causes renal damage, nor that cumulative lifetime doses exacerbate advanced CKDCitation83,Citation87,Citation88,Citation90–92.

Epidemiologic inferences that paracetamol may increase users’ risk of developing CKD are contentious; contradictory findings of observational studies suggest that putative associations might be due to protopathic bias and/or confounding by indication rather than signifying underlying causationCitation4,Citation87,Citation88,Citation90,Citation93. In particular, first-line use of paracetamol in preference to other analgesics by people with early renal impairment may lead to spurious associations with incident CKD in observational studiesCitation13,Citation87. Conversely, besides increasing the risk of GI bleeding, NSAIDs have proven nephrotoxic class effects and should be avoided where possible in patients with symptoms of renal impairment, as should COX-2 inhibitors which induce similar adverse effectsCitation83,Citation84,Citation86,Citation90,Citation94. Unlike COX-2 inhibitors, there have been no reports that therapeutic doses of paracetamol are associated with acute renal failureCitation95. Analysis of the large real-world JADER pharmacovigilance database supports the acute renal safety of paracetamol versus NSAIDsCitation1.

Prevailing guidance from the US Kidney Foundation and other nephrology experts, advocates stepwise escalation of analgesia, starting with non-opioids for mild pain, and recommends paracetamol as the preferred first-line analgesic for episodic treatment of mild pain in patients with renal dysfunction, CKD, and/or requiring dialysisCitation83,Citation84,Citation86,Citation90,Citation92,Citation95. Concordantly, a recent meta-analysis found paracetamol to be the mainstay of treatment for mild to moderate pain in CKD patientsCitation85. Dose modification is not necessary for patients on dialysis, who may take 1 g orally 3–4 times per dayCitation86. Among CKD patients on hemodialysis, 500 mg peroral paracetamol has been used to treat headaches, shivering, or feverCitation96. However, dose minimization may sometimes be warrantedCitation84; for example, a maximum of 3 g/day has been recommended for patients with advanced kidney failureCitation83.

Asthma

Several studies over the years have investigated the hypothesis that adulthood asthma might be related to paracetamol useCitation97–105; however, almost all were non-interventional association studies ()Citation106, and only one analyzed whether occasional use of paracetamol affects symptom severity in adults with established asthmaCitation101. Consequently, there is a paucity of high-quality clinical evidence on which to base guidanceCitation107.

Table 2. Reported associations between frequency of paracetamol exposure and asthma incidence or prevalence.

Epidemiological studies have consistently shown that paracetamol is associated with asthma incidence/prevalence, especially with more frequent exposureCitation97,Citation99,Citation101–104. These positive associations do not prove causality and may be partly attributable to confounding factors or biases, particularly people with asthma avoiding NSAIDs and preferentially using paracetamol. Nevertheless, accruing evidence supports a weak association between having asthma and frequent paracetamol useCitation14,Citation99,Citation101–104,Citation106,Citation108,Citation109. Asthma etiology hypothetically involves depletion of glutathione, an antioxidant that abates airway inflammationCitation101,Citation102,Citation108,Citation109, though some doubt that this is significant at standard therapeutic doses of paracetamolCitation23. Glutathione depletion also suppresses T-helper 1 production, thus favoring allergenic T-helper 2 responsesCitation102,Citation108. Other biologically plausible mechanisms are antigenic effects of paracetamol that stimulate immunoglobulin E responses, and COX inhibition that increases leukotriene levels and reduces prostaglandin E2 productionCitation14,Citation99,Citation104,Citation108.

On the other hand, epidemiological studies found no significant associations with asthma among the least frequent paracetamol users ()Citation97,Citation99,Citation101,Citation103. In one study, increasing asthma severity was associated with weekly or daily paracetamol use, whereas monthly users were no more likely to have asthma compared with never usersCitation101. However, in the only RCT to date in adults, 1 g paracetamol taken twice daily for 12 weeks had no statistically significant effect on the severity or control of stable mild to moderate asthma, probably ruling out overt morbid effects with short-term, low-dose useCitation105.

Analgesic-induced asthma

Aspirin and other NSAIDs provoke bronchospasm and exacerbate asthma in up to ∼20% of asthmatics who are hypersensitive to COX inhibitors; these acute reactions may be severe, even life-threateningCitation1,Citation107–111. Although most people with asthma tolerate paracetamol well, its weak COX inhibitory action has dose-dependent bronchospastic effects in 20–30% of individuals with aspirin-induced asthma (AIA) who are cross-sensitive to paracetamolCitation107,Citation109. In one study, 17 of 50 patients with AIA had bronchospastic reactions to paracetamol challenges of 1 g/day or 1.5 g/dayCitation112. However, less than 2% of asthmatics overall are hypersensitive to paracetamol, and such reactions are generally mild, occur at high doses, and are not known to have caused fatalitiesCitation107,Citation109,Citation111,Citation112. Most people with asthma, even those with AIA, have little risk of bronchospasm at paracetamol doses of <650 mgCitation112. The JADER database showed little sign of asthma induction with real-world use of paracetamol compared with NSAIDsCitation1.

Given the risks of hypersensitivity and GI bleeding associated with NSAIDs, paracetamol may be preferable for short-term treatment of mild to moderate pain in people with asthmaCitation6,Citation14,Citation99,Citation101,Citation107,Citation110,Citation111. Although there are no RCTs on the respiratory effects of short-term standard doses of paracetamol in adults with established asthma, available evidence suggests that episodic paracetamol use does not exacerbate respiratory symptomsCitation1,Citation14,Citation99,Citation105,Citation109. However, people with AIA that is known to be cross-sensitive to paracetamol should use the lowest effective single dose, for example, ≤500 mg per dosing occasionCitation14,Citation109,Citation110,Citation113.

Older age

Pain is considerably more common among people older than 60 versus younger adults and affects up to half or more of older community-dwellers, with even higher prevalence in elderly care home residentsCitation114,Citation115. But despite older adults being among the highest users of analgesics, their pain is often inadequately treated and significantly impairs their quality of lifeCitation5,Citation114–120. Managing pain in older people is often complicated by comorbidities, potential drug-drug interactions from polypharmacy, and age-related physiological and pharmacokinetic/dynamic changesCitation5,Citation119–122; however, a “start low and go slow” approach may make physicians over-cautious about up-titrating analgesic dosing as necessary, leading to undertreatmentCitation118. In such circumstances, paracetamol may be the first choice for treating mild to moderate acute painCitation6,Citation16,Citation69,Citation122, especially musculoskeletalCitation115, and is often prescribed to avoid using NSAIDs associated with increased risks of GI bleeding and renal dysfunction in older peopleCitation5,Citation16,Citation118,Citation121.

Drug interactions

Paracetamol may alter the International Normalized Ratio of oral anticoagulants, notably warfarin, potentially increasing the risk of bleedingCitation25,Citation122–124. There is no convincing evidence that other potential drug interactions with paracetamol are clinically significant ()Citation25,Citation124.

Table 3. Potential drug interactions with paracetamol and their clinical relevance.a

Paracetamol pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in older people

Although some guidance advocates reduced dosing of paracetamol for older people, there is limited supporting evidence, because this population is under-represented in clinical trials and the pharmacodynamics of paracetamol in older people have not been studied systematicallyCitation5,Citation118,Citation120. Consequently, questions about whether or how therapeutic doses should be adapted for both frail and robust older people remain unresolvedCitation120,Citation125. Understanding the pharmacology of paracetamol in older people can help to improve pain managementCitation118.

Conjecture that gastric emptying slows with advancing age is based largely on indirect findings or small cohorts of aged people with related comorbidities (e.g. Parkinson’s disease, diabetes) and/or medication useCitation126,Citation127. Healthy older people, however, generally have gastric emptying rates within the normal range, and modestly slower emptying than in younger people is unlikely to be clinically significantCitation126–128. Paracetamol absorption was not impaired in healthy older study subjects and time to maximum plasma concentration also appeared unaffected by age ()Citation120,Citation128–131,Citation133; however, exposure to a 1 g intravenous dose increased with age because paracetamol had a longer elimination half-lifeCitation130 and somewhat slower clearance in older people compared with young adultsCitation130–133, with creatinine clearance rather than age determining the clearance rateCitation129. Paracetamol users aged 84–95 years who took three 1 g doses per day for 5 days consecutively had no drug accumulationCitation132, and although frail inpatients older than 70 who took 3–4 g/day for 5 days did have higher plasma concentrations than younger patients, none had abnormally elevated serum alanine aminotransferase, which suggests that slower clearance of therapeutic paracetamol doses in geriatric patients may not necessarily increase the risk of hepatotoxicityCitation117. A study of 36 inpatients ≥80 years old who received 3 g/day paracetamol (concomitant with other analgesics), found wide inter-individual variations in all pharmacokinetic metrics; however, only seven had an average plasma concentration above the predefined analgesic target of 10 mg/LCitation125. Pharmacokinetic analyses in 30 fit, older people given 1 g intravenous paracetamol after knee surgery also found large (unexplained) variability; in population simulations, 1 g/6 h achieved a steady state of 10 mg/L on average, whereas a longer dosing interval of 1 g/8 h resulted in underdosing for most patientsCitation134.

Table 4. Studies comparing paracetamol absorption, concentration, and elimination in older versus younger adults.

Despite decreasing volume of distribution and clearance of paracetamol with advancing ageCitation16,Citation118, most older people tolerate 1 g/6 h per day well, with no need for dose reduction provided physicians have carefully considered patient-specific risk factors such as liver disease, heavy alcohol intake, or renal insufficiencyCitation16,Citation119,Citation121. Although liver damage from standard therapeutic doses (0.5–1 g/4–6 h, max ≤4 g/day) rarely occurs in healthy older peopleCitation16, it may nevertheless be prudent to consider lower or less frequent doses in those with risk factors for hepatotoxicity, which include weighing <50 kg, renal insufficiency, concomitant medications inducing liver enzymes, hepatitis or chronic alcohol use, or glutathione-depleted statesCitation16; 0.5 g four times per day or 1 g thrice daily may be suitable for such patientsCitation16.

Speculation that paracetamol could increase the risk of hypothermia in vulnerable older adults remains unsubstantiatedCitation135–137. Rare case reports have linked pediatric hypothermia to therapeutic doses of paracetamolCitation135 and limited experimental data suggest that paracetamol (20 mg/kg lean body mass) may impair thermogenesis in adult subjects during cold stress, but not in thermoneutral conditionsCitation136,Citation137. However, the mechanisms are not well understood and there is currently no evidence that paracetamol at a standard dose is a factor in adult cold-related hypothermia deathsCitation135–137.

In summary, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that reduced paracetamol clearance with age is clinically significant, or to support routine dose reduction for older patientsCitation119,Citation120,Citation133. Although some guidelines provide general dosing advice, specific recommendations for managing acute pain in older people are lackingCitation16,Citation120. Based on pharmacokinetic data, adjusting the dose of paracetamol is generally unnecessaryCitation131,Citation133. A dose of 0.5–1 g every 4–6 h (maximum of 4 g/day) is probably appropriate for healthy older people, while it may be advisable for very elderly or frail people or those otherwise at increased risk for hepatotoxicity to take the lowest effective dose, not exceeding 3 g/dayCitation16,Citation132.

Conclusions and recommendations

Notwithstanding prevalent self-treatment with non-prescription OTC analgesics, acute pain is still among the most common reasons for visits to primary care physiciansCitation7,Citation10. Before recommending any analgesic, physicians must first weigh the potential risks versus benefit for each patientCitation2,Citation7,Citation14. Although paracetamol is very widely used, many patients and some physicians have misconceptions about its suitability and dosing, especially for people with underlying comorbidities or who are olderCitation3,Citation5,Citation17. Such uncertainties are compounded by under-representation of these patient populations in clinical studies and consequent lack of evidence-based guidance, particularly specific dosing recommendations, which results in inconsistent prescription and usage practicesCitation3,Citation5,Citation16,Citation17,Citation19,Citation22,Citation85,Citation118. While it is important to educate people that the maximum recommended dose of paracetamol for healthy individuals is 4 g/day, people should also avoid using too low a dose to relieve pain, which may lead them to use stronger, less safe, analgesicsCitation2,Citation5,Citation12,Citation17,Citation21,Citation22,Citation83. Given a lack of large-scale RCTs of paracetamol involving users with health concerns such as liver disease, older age and others reviewed herein, it becomes necessary to make recommendations based on pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic data, observational studies, expert opinion, and real-world pharmacovigilanceCitation1,Citation12,Citation19,Citation118. Considering this, it is important to bear in mind that because the perceived safety of paracetamol makes it the first-choice analgesic for many patients with comorbidities, epidemiological associations between paracetamol and hypertension, GI disorders, renal disease, and asthma could be largely attributable to protopathic bias and/or confounding by indicationCitation4,Citation13.

The weight of evidence accrued over many years indicates that adults who take paracetamol episodically (<14 days) at recommended doses have almost negligible risk of serious adverse effectsCitation2,Citation4,Citation6,Citation12; accordingly experts concur that paracetamol should still be considered a first-line analgesic for acute mild to moderate pain in patients with liver or kidney disease, CVD, GI disorders, asthma, and/or who are olderCitation6,Citation7,Citation14,Citation16,Citation20,Citation21,Citation24,Citation38,Citation39,Citation70,Citation83,Citation84,Citation99,Citation107,Citation110,Citation111,Citation115. Dose reduction is generally unnecessary but may be warranted in certain circumstances (); therefore, advice on appropriate dosing for paracetamol users with comorbidities or who are older should be based on careful consideration of relevant individual-specific factorsCitation16,Citation19.

Table 5. First-line analgesia for acute mild to moderate pain in adults with special health concerns.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare. GlaxoSmithKline authors conceived the review and were involved in establishing its terms of reference, and selected literature. GlaxoSmithKline employees reviewed manuscript drafts and suggested revisions, but the authors were independent in deciding which content and recommendations to include in their final version.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

John Alchin has received honorarium payments for serving as a member of the GlaxoSmithKline Global Pain Faculty. Arti Dhar and Kamran Siddiqui are employees of GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare. Paul J. Christo has received honorarium payments for serving as a member of the GlaxoSmithKline Global Pain Faculty, has also been a consultant/advisor to Eli Lilly and Y-mAbs Therapeutics, Inc., and undertakes paid media work via Algiatry, LLC; he receives grant funding from the US National Institute on Aging. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

AD and KS conceived the review. JA and PC advised on the review scope and literature search parameters. All authors revised manuscript drafts for important intellectual content and approved the final version submitted.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Yen-May Ong and Huw Williams PhD of MIMS, Singapore, and David Neil PhD, (affiliated to MIMS, Singapore, at time of writing), for providing medical writing support, which was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Notes

i Based on package leaflet for Panadol optizorb, 500 mg film-coated tablets Paracetamol. GlaxoSmithKline Dungarvan Ltd., Ireland. Users should read their own package leaflet, as exact recommendations vary between countries and products.

ii This review defines “episodic” as, short-term use as needed to treat intermittent acute pain episodes (e.g. headache, menstrual), as opposed to uninterrupted long-term use to treat chronic pain conditions (e.g. osteoarthritis).

References

- Ishitsuka Y, Kondo Y, Kadowaki D. Toxicological property of acetaminophen: the dark side of a safe antipyretic/analgesic drug? Biol Pharm Bull. 2020;43(2):195–206.

- Jóźwiak-Bębenista M, Nowak JZ. Paracetamol: mechanism of action, applications and safety concern. Acta Pol Pharm. 2014;71(1):11–23.

- Lau SM, McGuire TM, van Driel ML. Consumer concerns about paracetamol: a retrospective analysis of a medicines call centre. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e010860.

- Graham GG, Scott KF, Day RO. Tolerability of paracetamol. Drug Saf. 2005;28(3):227–240.

- The Gerontological Society of America. An interdisciplinary look at recent FDA policy changes for acetaminophen and the implications for patient care. In: From publication to practice. The Gerontological Society of America. 2011. [cited 2022 Feb 6]. https://secure.geron.org/cvweb/cgi-bin/msascartdll.dll/ProductInfo?productcd=1946_Acetaminophen.

- Klotz U. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) - a popular and widely used nonopioid analgesic. Arzneimittelforschung. 2012;62(8):355–359.

- Hunt RH, Choquette D, Craig BN, et al. Approach to managing musculoskeletal pain: acetaminophen, cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, or traditional NSAIDs? Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(7):1177–1184.

- Gaul C, Eschalier A. Dose can help to achieve effective pain relief for acute mild to moderate pain with over-the-counter paracetamol. Open Pain J. 2018;11(1):12–20.

- Graham GG, Davies MJ, Day RO, et al. The modern pharmacology of paracetamol: therapeutic actions, mechanism of action, metabolism, toxicity and recent pharmacological findings. Inflammopharmacology. 2013;21(3):201–232.

- Hersch C, Denis C, Sugar D. Frequency, nature and management of patient-reported severe acute pain episodes in the over-the-counter setting: results of an online survey. Pain Manag. 2019;9(4):379–387.

- GlaxoSmithKline Dungarvan Limited. Package leaflet: Panadol optizorb, 500 mg film-coated tablets Paracetamol. GlaxoSmithKline Dungarvan Ltd. County Waterford, Ireland 2019. [cited 2022 Feb 6]. https://www.ravimiregister.ee/Data/PIL_ENG/PIL_26938_ENG.pdf.

- Hayward KL, Powell EE, Irvine KM, et al. Can paracetamol (acetaminophen) be administered to patients with liver impairment? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;81(2):210–222.

- Battaggia A, Lora Aprile P, Cricelli I, et al. Paracetamol: a probably still safe drug. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(9):e57.

- McCrae JC, Morrison EE, MacIntyre IM, et al. Long-term adverse effects of paracetamol - a review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(10):2218–2230.

- Roberts E, Delgado Nunes V, Buckner S, et al. Paracetamol: not as safe as we thought? A systematic literature review of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(3):552–559.

- British Medical Journal. What dose of paracetamol for older people? Drug Ther Bull. 2018;56(6):69–72.

- Saab S, Konyn PG, Viramontes MR, et al. Limited knowledge of acetaminophen in patients with liver disease. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016;4(4):281–287.

- Wolf MS, King J, Jacobson K, et al. Risk of unintentional overdose with non-prescription acetaminophen products. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(12):1587–1593.

- Schweighardt AE, Juba KM. A systematic review of the evidence behind use of reduced doses of acetaminophen in chronic liver disease. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2018;32(4):226–239.

- Chandok N, Watt KDS. Pain management in the cirrhotic patient: the clinical challenge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(5):451–458.

- Imani F, Motavaf M, Safari S, et al. The therapeutic use of analgesics in patients with liver cirrhosis: a literature review and evidence-based recommendations. Hepat Mon. 2014;14(10):e23539.

- Bosilkovska M, Walder B, Besson M, et al. Analgesics in patients with hepatic impairment: pharmacology and clinical implications. Drugs. 2012;72(12):1645–1669.

- Lauterburg BH. Analgesics and glutathione. Am J Ther. 2002;9(3):225–233.

- Benson GD, Koff RS, Tolman KG. The therapeutic use of acetaminophen in patients with liver disease. Am J Ther. 2005;12(2):133–141.

- Caparrotta TM, Antoine DJ, Dear JW. Are some people at increased risk of paracetamol-induced liver injury? A critical review of the literature. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74(2):147–160.

- Massart J, Begriche K, Fromenty B. Cytochrome P450 2E1 should not be neglected for acetaminophen-induced liver injury in metabolic diseases with altered insulin levels or glucose homeostasis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2021;45(1):101470.

- Lee SS, Buters JT, Pineau T, et al. Role of CYP2E1 in the hepatotoxicity of acetaminophen. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(20):12063–12067.

- Kamali F, Thomas SH, Ferner RE. Paracetamol elimination in patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;35(1):58–61.

- Stachowiak A, Szałek E, Karbownik A, et al. The influence of diabetes mellitus on glucuronidation and sulphation of paracetamol in patients with febrile neutropenia. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2019;44(2):289–294.

- Prescott LF. Therapeutic misadventure with paracetamol: fact or fiction? Am J Ther. 2000;7(2):99–114.

- Prescott LF. Paracetamol, alcohol and the liver. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49(4):291–301.

- Benson GD. Acetaminophen in chronic liver disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;33(1):95–101.

- Andreasen PB, Hutters L. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) clearance in patients with cirrhosis of the liver. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1979;624:99–105.

- Heard K, Green JL, Bailey JE, et al. A randomized trial to determine the change in alanine aminotransferase during 10 days of paracetamol (acetaminophen) administration in subjects who consume moderate amounts of alcohol. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(2):283–290.

- Kuffner EK, Green JL, Bogdan GM, et al. The effect of acetaminophen (four grams a day for three consecutive days) on hepatic tests in alcoholic patients–a multicenter randomized study. BMC Med. 2007;5:13.

- Forrest JA, Adriaenssens P, Finlayson ND, et al. Paracetamol metabolism in chronic liver disease. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1979;15(6):427–431.

- Khalid SK, Lane J, Navarro V, et al. Use of over-the-counter analgesics is not associated with acute decompensation in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(9):994–999.

- Dwyer JP, Jayasekera C, Nicoll A. Analgesia for the cirrhotic patient: a literature review and recommendations. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29(7):1356–1360.

- Hillis WS. Areas of emerging interest in analgesia: cardiovascular complications. Am J Ther. 2002;9(3):259–269.

- Kovačević M, Vezmar Kovačević S, Miljković B, et al. The prevalence and preventability of potentially relevant drug-drug interactions in patients admitted for cardiovascular diseases: a cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pract. 2017;71(10):e13005.

- Antman EM, Bennett JS, Daugherty A, et al. Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an update for clinicians: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;115(12):1634–1642.

- Fanelli A, Ghisi D, Aprile PL, et al. Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risk with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors: latest evidence and clinical implications. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2017;8(6):173–182.

- White WB, Kloner RA, Angiolillo DJ, et al. Cardiorenal safety of OTC analgesics. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2018;23(2):103–118.

- Schjerning AM, McGettigan P, Gislason G. Cardiovascular effects and safety of (non-aspirin) NSAIDs. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(9):574–584.

- Fulton RL, Walters MR, Morton R, et al. Acetaminophen use and risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in a hypertensive cohort. Hypertension. 2015;65(5):1008–1014.

- Shorog EM, Alburikan KA. The utilization of nonprescription medications in Saudi patients with cardiovascular diseases. Saudi Pharm J. 2018;26(1):120–124.

- Nguyen QV. Letter by Nguyen regarding article, “Acetaminophen increases blood pressure in patients with coronary artery disease”. Circulation. 2011;123(25):e645.

- Chan AT, Manson JE, Albert CM, et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and the risk of cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2006;113(12):1578–1587.

- Turtle EJ, Dear JW, Webb DJ. A systematic review of the effect of paracetamol on blood pressure in hypertensive and non-hypertensive subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75(6):1396–1405.

- Montgomery B. Does paracetamol cause hypertension? BMJ. 2008;336(7654):1190–1191.

- Curhan GC, Willett WC, Rosner B, et al. Frequency of analgesic use and risk of hypertension in younger women. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(19):2204–2208.

- Forman JP, Rimm EB, Curhan GC. Frequency of analgesic use and risk of hypertension among men. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(4):394–399.

- Dedier J, Stampfer MJ, Hankinson SE, et al. Nonnarcotic analgesic use and the risk of hypertension in US women. Hypertension. 2002;40(5):604–608.

- Dawson J, Fulton R, McInnes GT, et al. Acetaminophen use and change in blood pressure in a hypertensive population. J Hypertens. 2013;31(7):1485–1490.

- Kurth T, Hennekens CH, Stürmer T, et al. Analgesic use and risk of subsequent hypertension in apparently healthy men. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(16):1903–1909.

- Aljadhey H, Tu W, Hansen RA, et al. Comparative effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on blood pressure in patients with hypertension. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2012;12:93.

- Pavličević I, Kuzmanić M, Rumboldt M, et al. Interaction between antihypertensives and NSAIDs in primary care: a controlled trial. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;15(3):e372–382.

- Ubeda A, Llopico J, Sanchez MT. Blood pressure reduction in hypertensive patients after withdrawal of effervescent medication. Pharmacoepidem Drug Safe. 2009;18(5):417–419.

- Benitez-Camps M, Morros Padrós R, Pera-Pujadas H, et al. Effect of effervescent paracetamol on blood pressure: a crossover randomized clinical trial. J Hypertens. 2018;36(8):1656–1662.

- Jarrett DR. Paracetamol and hypertension: time to label sodium in drug treatments? BMJ. 2008;336(7657):1324.

- Chalmers JP, West MJ, Wing LM, et al. Effects of indomethacin, sulindac, naproxen, aspirin, and paracetamol in treated hypertensive patients. Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1984;6(6):1077–1093.

- Furey SA, Vargas R, McMahon FG. Renovascular effects of nonprescription ibuprofen in elderly hypertensive patients with mild renal impairment. Pharmacotherapy. 1993;13(2):143–148.

- Radack KL, Deck CC, Bloomfield SS. Ibuprofen interferes with the efficacy of antihypertensive drugs. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ibuprofen compared with acetaminophen. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107(5):628–635.

- Sudano I, Flammer AJ, Périat D, et al. Acetaminophen increases blood pressure in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2010;122(18):1789–1796.

- MacIntyre IM, Turtle EJ, Farrah TE, et al. Regular acetaminophen use and blood pressure in people with hypertension: the PATH-BP trial. Circulation. 2022;145(6):416–423.

- The University of Edinburgh. Regular paracetamol use linked to raised blood pressure [press release]. The University of Edinburgh. Latest news. 2022 Feb 8. [cited 2022 Feb 10]. https://www.ed.ac.uk/news/2022/regular-paracetamol-use-linked-to-high-blood-press.

- Merlo J, Broms K, Lindblad U, et al. Association of outpatient utilisation of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and hospitalised heart failure in the entire Swedish population. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;57(1):71–75.

- Schwarz ES, Mullins ME. Paracetamol: is all the concern valid? Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(8):e48.

- Girard P, Sourdet S, Cantet C, et al. Acetaminophen safety: risk of mortality and cardiovascular events in nursing home residents, a prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(6):1240–1247.

- Bannwarth B. Gastrointestinal safety of paracetamol: is there any cause for concern? Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2004;3(4):269–272.

- Weil J, Colin-Jones D, Langman M, et al. Prophylactic aspirin and risk of peptic ulcer bleeding. BMJ. 1995;310(4):827–830.

- Lewis SC, Langman MJ, Laporte JR, et al. Dose-response relationships between individual nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NANSAIDs) and serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis based on individual patient data. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54(3):320–326.

- Savage RL, Moller PW, Ballantyne CL, et al. Variation in the risk of peptic ulcer complications with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(1):84–90.

- Garcia Rodríguez LA, Hernández-Díaz S. The risk of upper gastrointestinal complications associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, acetaminophen, and combinations of these agents. Arthritis Res. 2001;3(2):98–101.

- Rahme E, Pettitt D, LeLorier J. Determinants and sequelae associated with utilization of acetaminophen versus traditional nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in an elderly population. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(11):3046–3054.

- Krishnasamy S, Abell TL. Diabetic gastroparesis: principles and current trends in management. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9(Suppl 1):1–42.

- Severijnen R, Bayat N, Bakker H, et al. Enteral drug absorption in patients with short small bowel: a review. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(14):951–962.

- Kelly K, O’Mahony B, Lindsay B, et al. Comparison of the rates of disintegration, gastric emptying, and drug absorption following administration of a new and a conventional paracetamol formulation, using gamma scintigraphy. Pharm Res. 2003;20(10):1668–1673.

- GlaxoSmithKline. A two part pivotal pharmacokinetic study to evaluate the exposure and variability in absorption of paracetamol from a fast-dissolving tablet. In: GSK study register. GSK. 2005 [cited 2022 Feb 6]. https://www.gsk-studyregister.com/en/trial-details/?id=A1900265#documents-section.

- GlaxoSmithKline. A proof-of-principle study to evaluate the absorption of paracetamol in a gastric dysmotiliy model. In: GSK study register. GSK. 2006 [cited 2022 Feb 6]. https://www.gsk-studyregister.com/en/trial-details/?id=A1900385#documents-section.

- Wójcicki J, Gawrońska-Szklarz B. Pharmacokinetics of paracetamol in patients with gastric and duodenal ulcers. Pol J Pharmacol Pharm. 1984;36(1):59–63.

- Haderslev KV, Sonne J, Poulsen HE, et al. Paracetamol metabolism in patients with ulcerative colitis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46(5):513–516.

- Davison SN. Clinical pharmacology considerations in pain management in patients with advanced kidney failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(6):917–931.

- Pham PC, Khaing K, Sievers TM, et al. 2017 Update on pain management in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J. 2017;10(5):688–697.

- Davison SN, Rathwell S, George C, et al. Analgesic use in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2020;7:2054358120910329.

- Smyth B, Jones C, Saunders J. Prescribing for patients on dialysis. Aust Prescr. 2016;39(1):21–24.

- Park WY. Controversies in acetaminophen nephrotoxicity. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2020;39(1):4–6.

- Evans M, Fored CM, Bellocco R, et al. Acetaminophen, aspirin and progression of advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(6):1908–1918.

- Mihatsch MJ, Khanlari B, Brunner FP. Obituary to analgesic nephropathy–an autopsy study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(11):3139–3145.

- Henrich WL, Agodoa LE, Barrett B, et al. Analgesics and the kidney: summary and recommendations to the Scientific Advisory Board of the National Kidney Foundation from an Ad Hoc Committee of the National Kidney Foundation. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;27(1):162–165.

- Blantz RC. Acetaminophen: acute and chronic effects on renal function. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28(1 Suppl 1):S3–S6.

- Hiragi S, Yamada H, Tsukamoto T, et al. Acetaminophen administration and the risk of acute kidney injury: a self-controlled case series study. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:265–276.

- Barrett BJ. Acetaminophen and adverse chronic renal outcomes: an appraisal of the epidemiologic evidence. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28(1 Suppl 1):S14–S19.

- Harris RC, Breyer MD. Update on cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(2):236–245.

- Graham GG, Graham RI, Day RO. Comparative analgesia, cardiovascular and renal effects of celecoxib, rofecoxib and acetaminophen (paracetamol). Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8(12):1063–1075.

- Suprapti B, Nilamsari WP, Rachmania , et al. Medical problems in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing hemodialysis and their therapy. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2019;30(6):jbcpp-2019-0250.

- Barr RG, Wentowski CC, Curhan GC, et al. Prospective study of acetaminophen use and newly diagnosed asthma among women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(7):836–841.

- Thomsen SF, Kyvik KO, Skadhauge L, et al. Intake of paracetamol and risk of asthma in adults. J Asthma. 2008;45(8):675–676.

- Kelkar M, Cleves MA, Foster HR, et al. Prescription-acquired acetaminophen use and the risk of asthma in adults: a case-control study. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(12):1598–1608.

- Davey G, Berhane Y, Duncan P, et al. Use of acetaminophen and the risk of self-reported allergic symptoms and skin sensitization in Butajira, Ethiopia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(4):863–868.

- Shaheen SO, Sterne JA, Songhurst CE, et al. Frequent paracetamol use and asthma in adults. Thorax. 2000;55(4):266–270.

- Shaheen S, Potts J, Gnatiuc L, et al; GA2LEN. The relation between paracetamol use and asthma: a GA2LEN european case-control study. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(5):1231–1236.

- McKeever TM, Lewis SA, Smit HA, et al. The association of acetaminophen, aspirin, and ibuprofen with respiratory disease and lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):966–971.

- Etminan M, Sadatsafavi M, Jafari S, et al. Acetaminophen use and the risk of asthma in children and adults: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2009;136(5):1316–1323.

- Ioannides SJ, Williams M, Jefferies S, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled study of the effect of paracetamol on asthma severity in adults. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e004324.

- Weatherall M, Ioannides S, Braithwaite I, et al. The association between paracetamol use and asthma: causation or coincidence? Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(1):108–113.

- Levy S, Volans G. The use of analgesics in patients with asthma. Drug Saf. 2001;24(11):829–841.

- Lourido-Cebreiro T, Salgado FJ, Valdes L, et al. The association between paracetamol and asthma is still under debate. J Asthma. 2017;54(1):32–38.

- Karakaya G, Kalyoncu AF. Paracetamol and asthma. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003;4(1):13–21.

- Ichinose M, Sugiura H, Nagase H, et al. Japanese guidelines for adult asthma 2017. Allergol Int. 2017;66(2):163–189.

- Jenkins C, Costello J, Hodge L. Systematic review of prevalence of aspirin induced asthma and its implications for clinical practice. BMJ. 2004;328(7437):434.

- Settipane RA, Schrank PJ, Simon RA, et al. Prevalence of cross-sensitivity with acetaminophen in aspirin-sensitive asthmatic subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96(4):480–485.

- American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology. Aspirin-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease (AERD). In: AAAAI library articles: asthma. AAAAI. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 6]. https://www.aaaai.org/Tools-for-the-Public/Conditions-Library/Asthma/Aspirin-Exacerbated-Respiratory-Disease-(AERD).

- Herr KA, Garand L. Assessment and measurement of pain in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2001;17(3):457–478.

- Abdulla A, Adams N, Bone M, et al. Guidance on the management of pain in older people. Age Ageing. 2013;42(Suppl 1):i1–i57.

- Gnjidic D, Murnion BP, Hilmer SN. Age and opioid analgesia in an acute hospital population. Age Ageing. 2008;37(6):699–702.

- Mitchell SJ, Hilmer SN, Murnion BP, et al. Hepatotoxicity of therapeutic short-course paracetamol in hospital inpatients: impact of ageing and frailty. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;36(3):327–335.

- McLachlan AJ, Bath S, Naganathan V, et al. Clinical pharmacology of analgesic medicines in older people: impact of frailty and cognitive impairment. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71(3):351–364.

- Aubrun F, Marmion F. The elderly patient and postoperative pain treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2007;21(1):109–127.

- Mian P, Allegaert K, Spriet I, et al. Paracetamol in older people: towards evidence-based dosing? Drugs Aging. 2018;35(7):603–624.

- Falzone E, Hoffmann C, Keita H. Postoperative analgesia in elderly patients. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(2):81–90.

- Kaas Oldenburg LI, Dalhoff KP, Sandoval LØ, et al. The risk of drug-drug interactions with paracetamol in a population of hospitalized geriatric patients. J Pharm (Cairo). 2020;2020:1354209.

- Sharma CV, Mehta V. Paracetamol: mechanisms and updates. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2014;14(4):153–158.

- Toes MJ, Jones AL, Prescott L. Drug interactions with paracetamol. Am J Ther. 2005;12(1):56–66.

- Hias J, Van der Linden L, Walgraeve K, et al. Pharmacokinetics of 2 oral paracetamol formulations in hospitalized octogenarians. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(3):1020–1030.

- Horowitz M, Maddern GJ, Chatterton BE, et al. Changes in gastric emptying rates with age. Clin Sci (Lond). 1984;67(2):213–218.

- Soenen S, Rayner CK, Horowitz M, et al. Gastric emptying in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 2015;31(3):339–353.

- Gainsborough N, Maskrey VL, Nelson ML, et al. The association of age with gastric emptying. Age Ageing. 1993;22(1):37–40.

- Triggs EJ, Nation RL, Long A, et al. Pharmacokinetics in the elderly. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1975;8(1):55–62.

- Liukas A, Kuusniemi K, Aantaa R, et al. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous paracetamol in elderly patients. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50(2):121–129.

- Divoll M, Abernethy DR, Ameer B, et al. Acetaminophen kinetics in the elderly. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1982;31(2):151–156.

- Bannwarth B, Pehourcq F, Lagrange F, et al. Single and multiple dose pharmacokinetics of acetaminophen (paracetamol) in polymedicated very old patients with rheumatic pain. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(1):182–184.

- Miners JO, Penhall R, Robson RA, et al. Comparison of paracetamol metabolism in young adult and elderly males. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;35(2):157–160.

- Mian P, van Esdonk MJ, Olkkola KT, et al. Population pharmacokinetic modelling of intravenous paracetamol in fit older people displays extensive unexplained variability. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(1):126–135.

- Agier MS, Chollet N, Bediou E, et al. Transient major hypothermia associated with acetaminophen: a pediatric case report and literature review. Arch Pediatr. 2019;26(6):358–360.

- Foster J, Mauger A, Thomasson K, et al. Effect of acetaminophen ingestion on thermoregulation of normothermic, non-febrile humans. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:54. Erratum in: Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:93.

- Foster J, Mauger AR, Govus A, et al. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) induces hypothermia during acute cold stress. Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37(11):1055–1065.