Abstract

Objective

The robust enrollment in SPARTAN and SAMURAI provided the opportunity to present post-hoc descriptive details on migraine disease characteristics and treatment outcomes after treatment with lasmiditan, a selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonist, in racial and ethnic subgroups.

Methods

Descriptive data from racial (White [W](n = 3471) and Black or African American [AA](n = 792)) and ethnic (Hispanic or Latinx [HL](n = 775) and Non-Hispanic or Latinx [Non-HL](n = 3637)) populations are presented on pooled data from two double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized Phase 3 studies (SAMURAI [NCT02439320] and SPARTAN [NCT2605174]). Patients were treated with lasmiditan (50 (SPARTAN only), 100, or 200 mg) or placebo for a single migraine attack of moderate-to-severe intensity. Efficacy data were recorded in an electronic diary at baseline, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. Safety was evaluated and reported by occurrences of adverse events.

Results

Clinical characteristics were generally similar across populations. W participants had longer migraine history than AA participants, and Non-HL participants had more migraine disability than HL participants. In the lasmiditan single-attack studies, AA participants waited longer than W participants to take study drug. A higher proportion of HL participants rated baseline migraine severity as severe compared to Non-HL participants. Response to lasmiditan was similar across racial and ethnic groups, including pain response, freedom from most bothersome symptom and migraine-related disability, and safety and tolerability. Across multiple outcomes, AA and HL participants tended to report more positive outcomes.

Conclusions

There were few differences in demographic and clinical characteristics across racial and ethnic groups. Similar lasmiditan efficacy and safety outcomes were observed in AA versus W participants, and in HL versus Non-HL participants. Small observed differences may be driven by a tendency toward a more positive response observed across all treatment groups by AA and HL participants.

Introduction

Migraine is a common neurological disease characterized by moderate-to-severe head pain accompanied by symptoms including photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and vomitingCitation1. Migraine is a significant health burden and is ranked as the second highest cause of disability worldwideCitation2,Citation3. Despite the significant disease burden of migraine, the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study reported that more than 40% of patients with episodic migraine have significant unmet needs, such as high rates of headache-related disability and dissatisfaction with their current treatment regimenCitation4.

Data from the National Health Interview Survey from 2005 to 2012 suggest that prevalence of severe headache or migraine is highest among American Indian Alaskan Native (AIAN) patients (17.7%) followed by White (W) (15.5%), Latinx (14.5%), Blacks or African American (AA) (14.45%), and Asian (9.2%) patientsCitation5. Stewart et al.Citation6 found that in female patients migraine prevalence was significantly higher in W patients (20.4%) than in AA(16.2%) or Asian American (9.2%) patients. These differences have been attributed to factors associated with increased susceptibility to migraine, increased sensitivity to migraine triggers, or in the underdiagnosis of migraine in racial or ethnic Non-WhitesCitation6,Citation7. The potential for underdiagnosis is supported by a finding from the AMPP that demonstrated the prevalence of probable migraine is significantly higher in AA patients than in W patients, reflecting race-related disparity in symptom reportingCitation8.

Racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare have been well documented, including in the area of pain treatmentCitation9,Citation10. Within the area of migraine specifically, there is limited literature with few clear and replicated findings. Research findings suggest that AA patients are less likely to be prescribed acute migraine medication compared to W patientsCitation7. While preventive medications are generally underutilized, one report found that when prescribed, AA patients were slightly more likely to receive high-quality preventive medications compared to Hispanic or non-Hispanic White patientsCitation11. Similar outcomes were observed between racial and ethnic groups treated in real-world settings with acute (i.e. 6 mg of subcutaneous sumatriptan) and/or preventive treatmentsCitation9,Citation12. More patients in a diverse Non-White group (including patients identified as Black, Hispanic, or other) reported severe pain and clinical disability and also waited longer before treating headache pain compared to W patientsCitation12.

Lasmiditan is a selective serotonin (5-HT1F) receptor agonist (ditan)Citation13–15 approved for use in the United States for the acute treatment of migraine with or without aura in adults. Two Phase 3 trials (SAMURAI and SPARTAN) demonstrated that more participants who treated a migraine attack with lasmiditan were free from headache pain and free from their most bothersome symptom (MBS) at 2 h post-dose compared to participants treated with placeboCitation16,Citation17. Common treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) associated with lasmiditan were generally neurologic, mild to moderate in severity, and included dizziness, paresthesia, somnolence, fatigue, and nauseaCitation18. The efficacy of lasmiditan is generally similar across many patient groups, including by raceCitation19.

Healthcare disparities extend to participation in clinical trials, the foundation upon which drug approvals are based. Increased diversity in clinical trials is critical to ensure that medications are safe and effective for all patientsCitation20,Citation21. The lasmiditan Phase 3 program enrolled a significant sample of AA and Hispanic or Latinx (HL) participants, allowing for post-hoc examination of racial and ethnic differences in baseline demographics, migraine characteristics, and efficacy and safety responses to lasmiditan for treatment of a single migraine attack.

Materials and methods

Study design

Post-hoc analyses were conducted on pooled data from two double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, multi-center, Phase 3 studies of similar design in which participants with episodic migraine were treated with lasmiditan or placebo for a single attack of moderate-to-severe intensity. The studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and internationally accepted standards of Good Clinical Practice. All participants provided written informed consent. Detailed descriptions of the SAMURAI (NCT02439320) and SPARTAN (NCT02605174) study designs can be found in their primary reportsCitation16,Citation17.

The SAMURAI trial evaluated two doses of lasmiditan (100 and 200 mg), while the SPARTAN trial evaluated three doses (50, 100, and 200 mg). Participants were randomized to either treatment or placebo in the SAMURAI and SPARTAN trials (1:1:1 and 1:1:1:1, respectively). Participants were asked to treat a single migraine attack (at least moderate in severity, and not improving) within 4 h of headache onset. Participants recorded their response to the first dose over the next 48 h in an electronic diary. If the migraine did not respond to treatment within 2 h or if it resolved but recurred after 2 h, participants could take a second dose of the study drug up to 24 h after the onset of migraine. This post-hoc analysis is limited to discussion of outcomes among racial and ethnic groups at 2 h after the first dose only.

Trial population

The SAMURAI and SPARTAN trials were conducted in participants aged ≥18 years, diagnosed with migraine based on the International Classification of Headache Disorders-IICitation22,Citation23 with a history of migraine for ≥1 year, and with migraine onset before the age of 50. Participants were required to have at least moderate migraine disability (Migraine Disability Assessment Score ≥11) and to experience three to eight migraine attacks per month.

This post-hoc analysis focused on pooled racial and ethnic populations from the safety populations of the SAMURAI and SPARTAN trials. Analyses were conducted on W (n = 3471) and AA (n = 792) participants and, separately, on HL (n = 775) and Non-Hispanic or Latino (Non-HL) (n = 3637) participants.

Data collection and patient-reported outcomes

Participants self-reported ethnicity and race, with the ethnicity question limited to identification as either HL or Non-HL, consistent with regulatory guidanceCitation24.

Patient demographics, including CV history and risk, are reported. Cumulative count of cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs) of interest included the six variables that the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines concluded were the most robust variables for prediction of a first CV event ( and )Citation25,Citation26.

Table 1. Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics by race.

Table 2. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics by ethnicity.

An electronic diary was used to collect efficacy data at baseline; 30, 60, 90, and 120 min; and 24 and 48 h after treatment. Consistent with recommendations from the International Headache SocietyCitation27, outcome at 2 h was the primary objective. Data recorded in the diary captured the characteristics of the treated migraine attack, headache severity, headache pain, freedom from MBS, and level of migraine-related functional disability. Headache freedom was defined as a reduction in headache severity from mildCitation1, moderateCitation2, or severeCitation3 at baseline to none (0). MBS was self-identified by the patient from the associated symptoms of photophobia, phonophobia, or nausea. A full description of each of these measures has been described previouslyCitation28. The proportions of participants in each racial and ethnic population who reported headache pain freedom, freedom from MBS, headache pain relief, and freedom from migraine-related functional disability at 2 h are reported. Patients also recorded any unusual symptom (possible adverse event) experienced during the treatment period; these were reviewed and documented at an in-person assessment. A full description of safety data procedures is presented separatelyCitation18.

Statistical analysis

These studies were not designed or powered to make statistical comparisons to placebo within racial and ethnic groups. However, given relatively large samples of AA (n = 792) and HL (n = 775) patients enrolled in the lasmiditan Phase 3 program, post-hoc descriptive analyses are presented. Pain freedom and MBS freedom were analyzed in the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population ( and ), whereas pain relief and migraine-related disability were analyzed in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population ( and ). Full descriptions of participants within these populations can be found in the primary manuscripts for both studiesCitation16,Citation17. The proportion of patient-reported pain freedom, MBS freedom, headache pain relief, and freedom from migraine-related functional disability in each treatment group was computed.

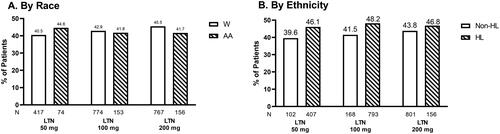

Figure 1. mITT population experiencing pain freedom at 2 h. Proportions of W and AA participants (A) and Non-HL and HL participants (B) in mITT population experiencing pain-freedom at 2 h following treatment with placebo, lasmiditan 50 mg, 100 mg, or 200 mg from post-hoc analyses of SAMURAI and SPARTAN studies. Denominators for calculating percentages are the counts of patients experiencing mild, moderate, or severe headache pain at baseline. Participants in SAMURAI did not take LTN 50 mg. Dashed bars indicate AA (A) and HL (B) participants. Abbreviations. AA, Black or African American; HL, Hispanic or Latinx; LTN, lasmiditan; mITT, modified intent-to-treat; Non-HL, Non-Hispanic or Latinx; PBO, placebo; W, White.

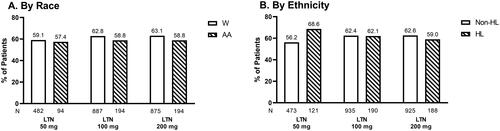

Figure 2. mITT population experiencing freedom from MBS at 2 h. Proportions of W and AA participants (A) and Non–HL and HL participants (B) in mITT population experiencing freedom from MBS 2 hours following treatment with placebo, lasmiditan 50 mg, 100 mg, or 200 mg from post-hoc analyses of SAMURAI and SPARTAN studies. Denominators for calculating percentages in each racial and ethnicity group is the counts of participants within each category divided by the number of participants in the analysis population. Participants in SAMURAI did not take LTN 50 mg. Dashed bars indicate AA (A) and HL (B) participants. Abbreviations. AA, Black or African American; HL, Hispanic or Latinx; LTN, lasmiditan; MBS, Most Bothersome Symptom; mITT, modified intent-to-treat; Non-HL, Non-Hispanic or Latinx; PBO, placebo; W, White.

Figure 3. ITT population experiencing pain relief at 2 h. Proportions of W and AA participants (A) and Non-HL and -HL participants (B) in ITT population experiencing pain relief 2 h following treatment with placebo, lasmiditan 50 mg, 100 mg, or 200 mg from post-hoc analyses of SAMURAI and SPARTAN studies. Denominators for calculating percentages in each racial and ethnicity group category is the counts of participants within each specific category divided by the number of participants in the analysis population. Participants in SAMURAI did not take LTN 50 mg. Dashed bars indicate AA (A) and HL (B) participants. Abbreviations. AA, Black or African American; HL, Hispanic or Latinx; ITT, intent-to-treat; LTN, lasmiditan; Non-HL, Non-Hispanic or Latinx; PBO, placebo; W, White.

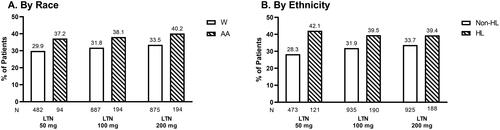

Figure 4. ITT population experiencing no migraine-related disability at 2 h. Proportions of White and AA participants (A) and Non-HL and HL participants (B) in ITT population experiencing no migraine-related disability 2 h following treatment with placebo, lasmiditan 50 mg, 100 mg, or 200 mg from post-hoc analyses of SAMURAI and SPARTAN studies. Denominators for calculating percentages are the counts of participants with non-missing assessment at baseline. Participants in SAMURAI did not take LTN 50 mg. Dashed bars indicate AA (A) and HL (B) participants. Abbreviations. AA, African American; HL, Hispanic or Latinx; ITT: intent-to-treat; LTN, lasmiditan; Non-HL, Non-Hispanic or Latinx; PBO, placebo; W, White.

Categorical measures were summarized with frequency and percentage, and continuous measures were reported using descriptive statistics.

Results

Disease characteristics and demographics

Study population by race

The pooled population included patients with an average age of 39 years (AA patients) and 43 years (W patients) with the majority of patients being female (80.8%, AA and 84.9%, W) (). Clinical characteristics were largely similar across both groups; however, W patients experienced a longer average duration of migraine history (20 years) compared to AA patients (14 years). Fewer AA patients reported concomitant use of preventive migraine medication (17.8%) compared to W patients (23.1%). Both populations presented with CVRFs, with AA participants (39.3%) and W participants (42.5%) having two or more CVRFs from a predefined list. In the AA population, there were higher proportions of participants reporting high blood pressure, diabetes (total), obesity, and smoking history (currently smoking) compared to W participants (). In contrast, the W population had higher proportions of participants aged >40 years, with high total cholesterol, and a family history of coronary artery disease (CAD) ().

Study population by ethnicity

The study population included participants with an average age of 48 years (HL) and 42 years (Non-HL), with the majority of the participants being female, (83.1%, HL and 84.1%, Non-HL) (). Clinical characteristics were similar across both groups, although a higher mean migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) score was reported in the Non-HL (32.9) compared to the HL population (27.8). Concomitant use of preventive migraine medication was also higher in Non-HL participants (23.1%) compared to HL participants (16.8%). Both populations reported having CVRFs, with 41.3% of HL and 41.2% of Non-HL participants reporting two or more CVRFs from a predefined list. There were higher proportions of HL participants with low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and with a history of diabetes mellitus (). Conversely, higher proportions of Non-HL participants reported being current smokers, being obese, having a history of migraine with aura, and having a family history of CAD ().

Characteristics of treated migraine

Observations by race

AA participants waited, on average, longer from the time of migraine pain start (2.1 h) before taking the study drug compared to W participants (1.7 h), and a greater proportion of AA participants (34.2%) reported severe pain at the time of dosing compared to W patients (27.8%) (Supplementary Table 1). In both cohorts, photophobia was most often identified as the MBS (53.9% of AA participants and 53.7% of W participants) (Supplementary Table 1).

Observations by ethnicity

While time to dosing from migraine pain onset was similar in HL participants compared to Non-HL participants, a higher proportion of HL participants rated their baseline migraine severity as severe (37.2%) compared to the Non-HL participants (27.0%) (Supplementary Table 2). In both cohorts, photophobia was most often identified as the MBS (54.1% of HL participants and 54.0% of Non-HL participants) (Supplementary Table 2).

Response to placebo

Observations by race

Across all 2-h efficacy outcomes, AA participants reported increased response to placebo relative to W participants (Pain freedom 26.8% vs. 16.8%; Freedom from MBS 41.4% vs. 29.7%; Pain relief 57.6% vs 42.8%; and No migraine-related disability 35.1% vs. 21.0%).

Observations by ethnicity

Across all 2-h efficacy outcomes, HL participants reported increased response to placebo relative to Non-HL participants (Pain freedom 28.0% vs. 16.3%; Freedom from MBS 43.4% vs. 29.0%; Pain relief 54.2% vs 43.1%; and No migraine-related disability 33.9% vs. 20.9%).

Pain-freedom at 2 h

Observations by race

In the AA population, the proportion of participants reporting pain freedom at 2 h post-dose was 37.3%, 31.4%, and 37.2% among participants treated with 50, 100, and 200 mg lasmiditan, respectively (). In the W population, the proportion of participants reporting pain freedom at 2 h post-dose was 26.8%, 29.5%, and 35.2% among participants, treated with 50, 100, and 200 mg lasmiditan, respectively ().

Observations by ethnicity

In the HL subpopulation, the proportion of participants reporting pain freedom at 2 h post-dose was 36.5%, 35.4%, and 41.3% of participants, treated with 50, 100, and 200 mg lasmiditan, respectively (). The proportion of Non-HL participants reporting pain freedom at 2 h post-dose was 26.5%, 29.0%, and 34.3% of participants treated with 50, 100, and 200 mg lasmiditan, respectively ().

MBS-free at 2 h

Observations by race

At 2 h post-dose, 44.6%, 41.8%, and 41.7% of AA participants treated with 50, 100, and 200 mg lasmiditan, respectively, reported freedom from MBS (). In the W population, 40.5%, 42.9%, and 45.5% of participants treated with 50, 100, and 200 mg lasmiditan, respectively, reported freedom from MBS at 2 h post-dose ().

Observations by ethnicity

Freedom from MBS at 2 h post-dose was reported by 46.1%, 48.2%, and 46.8% of HL participants treated with 50, 100, and 200 mg lasmiditan, respectively (). In the Non-HL population, freedom from MBS at 2 h post-dose was reported by 39.6%, 41.5%, and 43.8% of participants treated with 50, 100, and 200 mg lasmiditan, respectively ().

Headache pain relief

Observations by race

In the AA population, 57.4%, 58.8% and 58.8% of participants treated with lasmiditan (50, 100, and 200 mg, respectively) reported pain relief 2 h post-dose (). While in the W population, 59.1%, 62.8%, and 63.1% of participants treated with lasmiditan (50, 100, and 200 mg, respectively) reported pain relief 2 h post-dose ().

Observations by ethnicity

At 2 h post-dose, 68.6%, 62.1%, and 59% of HL participants treated with lasmiditan (50, 100, and 200 mg, respectively) reported pain relief (). Of the Non-HL population, 56.2%, 62.4%, and 62.6% of participants treated with lasmiditan (50, 100, and 200 mg, respectively) reported pain relief 2 h post-dose ().

Patient-reported freedom from migraine-related functional disability

Observations by race

In the AA population, 37.2%, 38.1% and 40.2% of participants treated with lasmiditan (50, 100, and 200 mg, respectively) rated their migraine-related disability as “none” (). Within W participants, 29.9%, 31.8%, and 33.5% treated with lasmiditan (50, 100, and 200 mg, respectively) reported their migraine-related disability as “none” at 2 h post-dose ().

Observations by ethnicity

At 2 h post-dose, 42.1%, 39.5%, and 39.4% of HL participants treated with lasmiditan (50, 100, and 200 mg, respectively) rated their migraine disability as “none” (). Within Non-HL participants, 28.3%, 31.9%, and 33.7% of Non-HL participants treated with lasmiditan (50, 100, and 200 mg, respectively) rated their migraine disability as “none” at 2 h post-dose ().

Safety overview

Observations by race

Few serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported with an overall incidence of 0.2% reported across the combined W and AA populations (). In both populations, the likelihood of experiencing TEAEs increased with higher doses. Additionally, across all doses of lasmiditan, the percentage individual patients reporting TEAEs was lower in the AA participant population compared to the W participant population (). In the AA population, TEAEs were reported in 13.5% placebo, and 15.1%, 27.4%, and 29.9% of participants treated with 50, 100, and 200 mg of lasmiditan, respectively. In the W population, TEAEs were reported in 13.9% of participants treated with placebo and 26.9%; 38%, and 43% of participants treated with 50, 100, and 200 mg of lasmiditan, respectively. The pattern of common TEAEs was similar in both populations with dizziness as the most frequently reported TEAE.

Table 3. Overview of safety by race (Safety population).

Observations by ethnicity

A similar trend was observed when safety was examined by ethnicity. Few SAEs were reported in either ethnic subgroup with an overall incidence of 0.3% of the combined HL and Non-HL populations (). In both populations, the likelihood of experiencing TEAEs increased in higher doses. Across all doses of lasmiditan, the percentage of reported TEAEs was lower in the HL population compared to the Non-HL populations (). In the HL population, TEAEs were reported in 13.9% of participants treated with placebo and 18.5%, 28.8%, and 26.8% of participants treated with 50, 100, and 200 mg of lasmiditan, respectively, compared to 13.7% of Non-HL participants treated with placebo and 27.0%, 37.8%, and 43.3% of Non-HL participants treated with 50, 100, and 200 mg of lasmiditan, respectively. The pattern of common TEAEs was similar in both populations.

Table 4. Overview of safety by ethnicity (Safety population).

Discussion

Racial and ethnic disparities in health care have received increasing attention in recent yearsCitation10 including the under-representation of diverse racial and ethnic populations in clinical trials. The reasons behind racial disparities in healthcare are numerous and complexCitation29 but may include differential disease characteristics, access to care, distrust of medical institutions, lack of representation in research, cultural differences, implicit and explicit biases, and social determinants of healthCitation30. Moreover, race is not inherently biological, but rather a social construct that act as a conduit for systemic racism that has significant impact on social determinants of health and health outcomesCitation31,Citation32.

The lasmiditan Phase 3 development program enrolled a sizeable sample of AA (n = 792; 19%) and HL (n = 775; 18%) participants. The commitment to improving the diversity and representation of all groups in the lasmiditan Phase 3 program allows for additional exploration and understanding of differences in characteristics of migraine pain, response to migraine symptoms, treatment needs, and lasmiditan treatment in these groups.

In our study population, W participants were slightly older and had a longer history of migraine compared to AA participants. While Charleston and BurkeCitation11 found that AA patients were more likely to be prescribed high-quality preventives, we found that overall fewer AA participants were prescribed preventive migraine medication than W participants. This finding was also observed for HL participants relative to Non-HL participants.

Migraine is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular diseaseCitation33,Citation34 and is associated with a number of CV eventsCitation35–40. Approximately two million women and 665,000 men in the United States have episodic migraine and a history of ≥1 CV event, condition, or procedure that may limit their use of triptans, which are a commonly prescribed acute treatment for migraineCitation41. Lasmiditan does not cause vasoconstriction in coronary arteriesCitation13, Citation42,Citation43 and does not have the same contraindications in patients with CV history as triptans. Our analysis suggests that AA and HL participants had similar levels of CV risk as W and Non-HL participants, although that risk presented differently across groups. As options for acute treatment of migraine attacks are limited in patients with prior history of CV and cerebrovascular diseases and CVRFs, lasmiditan may be a helpful addition to the treatment algorithm for these patients.

Consistent with one previous studyCitation12, AA participants waited longer from the onset of pain to take study drug, and both AA and HL participants were more likely to wait to treat until the pain was severe in comparison to W and Non-HL participants. While conclusions based on behavior in this single-attack clinical trial are limited, it is possible that AA patients and HL participants may age in a “high-coping” strategy in pain treatment, attempting multiple alternative interventions before taking medicineCitation44. The benefits of treating early (i.e. at the onset of pain) have been well documented but, despite this, 69% of patients with migraine report that they do not treat their migraine pain as soon as they feel painCitation45. The most common reason patients quote for not treating their pain at onset is the desire to reserve medication for a more severe migraineCitation46. It is possible that the behavior to reserve acute treatment, even in the clinical trial setting, may also be an artifact of delayed, inconsistent, or inadequate access to quality migraine treatment.

This report builds upon previous work showing that patient characteristics were not predictive of the efficacy of a single-dose lasmiditan as determined by headache pain freedom and MBS freedom at 2 h post-doseCitation19. In this descriptive report, there were no clearly meaningful differences in response to lasmiditan at doses of 50, 100, and 200 mg among racial or ethnic groups, with all groups experiencing benefits in pain freedom, pain relief, freedom from MBS, and a reduction in migraine-related disability, at 2 h after treatment. While rates of reported TEAEs differed slightly across groups, all racial and ethnic groups reported a similar pattern of TEAEs consistent with the known tolerability profile of lasmiditan. This report further documents the benefits of lasmiditan for acute treatment of migraine in multiple subsets of patients, including: patients of differing racial/ethnic backgrounds, patients reporting previous insufficient response to triptansCitation47 patients on migraine preventive drugsCitation48, patients with cardiovascular risk factorsCitation26, and patients with difficult to treat migraine disease or attacksCitation19.

Placebo effect in trials assessing acute treatments for migraine vary from 6% to 47%, highlighting the strong potential effect of placebo and other demand characteristics of the clinical trial settingCitation49. Placebo effects may also play a role in augmenting the reported effectiveness of treatmentCitation50. A systemic review of placebo response in clinical trials of neuropathic pain reported higher rates of placebo response in trials including non-W participantsCitation51. In the lasmiditan Phase 3 studies, AA and HL participants reported greater response to placebo than W and Non-HL participants in the outcomes of headache pain freedom and relief, freedom from MBS, and freedom from migraine-related disability. It is possible that this tendency for positive response may also explain small numerical advantages present for some treatment groups and efficacy outcomes in the AA populations and HL population. Similarly, AA and HL participants reported fewer TEAEs compared to W and Non-HL participants. Patient outcomes can be mediated by features of the clinical encounter, such as perceptions of clinician warmth, empathy, support, and interestCitation50. Research on health care disparities has documented that people of color may have less positive, supportive clinical encountersCitation50. It is possible that AA participants and HL participants were differentially impacted by the care provided in the clinical trial environment, and that may have contributed toward this observed trend to report more favorable outcomes. In any case, further work is needed to replicate and understand this finding.

These studies were designed to inform on the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of lasmiditan for the acute treatment of migraine in adults. As such, the studies did not include variables that might have been helpful to interpret our findings, such as detailed health care history, including consistent access to qualified providers and preventive and acute care, socioeconomic status, and metropolitan statistical area. This is a limitation of this report.

The efforts to recruit and enroll a diverse population in the lasmiditan Phase 3 program resulted in improved representation of AA and HL participants relative to historical trials. However, concerns regarding recruitment of diverse participants into clinical trials persist, with a recent study reporting that AA participants are less willing to participate in most types of studies when compared to non-Hispanic White participantsCitation52. Furthermore, Hispanic participants are less willing than W participants to participate in those studies that are perceived to be invasiveCitation52. Additionally, the lasmiditan Phase 3 program did not recruit and enroll sufficient proportions of other underrepresented ethnic groups in medicine, e.g. American Indian or Alaska Natives, or other racial/ethnic groups to enable meaningful analyses in these populations. Sponsors must continue to ensure that all populations have the opportunity to participate in clinical research, through expanded recruitment and retention efforts. Clinical trial sites should include diverse investigators and be located in communities convenient to diverse patient populations. Additionally, the use of virtual visits, acknowledgement and discussion of potential distrust, reduced study procedures, and making eligibility requirements more inclusive may help to address the disparitiesCitation53. While the lasmiditan Phase 3 program suggests that it is possible to achieve greater racial and ethnic diversity in clinical research, there is still much work to be done to continue to increase this trend.

Conclusions

The inclusion of historically underrepresented racial and ethnic groups in migraine research in the lasmiditan Phase 3 trials enabled assessment of migraine history and response to lasmiditan in W and AA participants and in HL and Non-HL participants. There were few differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, and efficacy and safety of lasmiditan across racial and ethnic groups. Small observed differences may be driven by a tendency toward a more positive response observed in AA and HL participants. Further work is needed to explore several observations found in this post-hoc analysis and to ensure increased representation of diverse groups in clinical trials.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA. The SAMURAI and SPARTAN clinical trials, which were the source of the data analyzed, were funded by CoLucid Pharmaceuticals, Inc. CoLucid is a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly and Company.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

LC has received personal compensation for serving as a consultant for Allergan/AbbVie, Alder/Lundbeck, Amneal, Biohaven, Satsuma and Teva; is on the advisory panel for Ctrl M Health (stock); received grant support from the Disparities in Headache Advisory Council; served as an Expert Witness for Vaccine Injury Compensation Program. He is a non-compensated associate editor for Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain and serves as a non-compensated Board Member-at-Large for the Alliance for Headache Disorders Advocacy and the Clinical Neurological Society of America. ED, Sonja B, Simin B are employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. BSE has no conflicting interests. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

Conception: LC, ED, Simin B; design: ED: data analysis: Simin B; interpretation of the data: all authors; drafting of the paper: all authors; critical revisions for intellectual content: all authors; final version approval to be published: all authors; all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplementary_Figure_1_PBO_population_response_at_2_hours.docx

Download MS Word (75.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study participants and investigators who participated in the lasmiditan studies. The authors would also like to express their gratitude to Sinéad Ryan (employee of Eli Lilly and Company) for medical writing support.

Data availability statement

Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

References

- Dodick DW. Migraine. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1315–1330.

- Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–1222.

- Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, et al. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):137.

- Lipton RB, Buse DC, Serrano D, et al. Examination of unmet treatment needs among persons with episodic migraine: results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache. 2013;53(8):1300–1311.

- Loder S, Sheikh HU, Loder E. The prevalence, burden, and treatment of severe, frequent, and migraine headaches in US minority populations: statistics from National Survey studies. Headache. 2015;55(2):214–228.

- Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Liberman J. Variation in migraine prevalence by race. Neurology. 1996;47(1):52–59.

- Nicholson RA, Rooney M, Vo K, et al. Migraine care among different ethnicities: do disparities exist? Headache. 2006;46(5):754–765.

- Silberstein S, Loder E, Diamond S, et al. Probable migraine in the United States: results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(3):220–229.

- Heckman BD, Holroyd KA, Tietjen G, et al. Whites and African-Americans in headache specialty clinics respond equally well to treatment. Cephalalgia. 2009;29(6):650–661.

- committee Iom. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2002 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.; 2003. (Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care).

- Charleston IL, Burke JF. Do racial/ethnic disparities exist in recommended migraine treatments in US ambulatory care? Cephalalgia. 2018;38(5):876–882.

- Burke-Ramirez P, Asgharnejad M, Fau-Webster C, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of subcutaneous sumatriptan for acute migraine: a comparison between ethnic groups. Headache. 2001;41(9):873–882.

- Nelson DL, Phebus LA, Johnson KW, et al. Preclinical pharmacological profile of the selective 5-HT1F receptor agonist lasmiditan. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(10):1159–1169.

- Rubio-Beltran E, Labastida-Ramirez A, Villalon CM, et al. Is selective 5-HT1F receptor agonism an entity apart from that of the triptans in antimigraine therapy? Pharmacol Ther. 2018;186:88–97.

- Clemow DB, Johnson KW, Hochstetler HM, et al. Lasmiditan mechanism of action - review of a selective 5-HT(1F) agonist. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):71–13.

- Kuca B, Silberstein SD, Wietecha L, et al. Lasmiditan is an effective acute treatment for migraine. Neurology. 2018;91(24):e2222–e2232.

- Goadsby PJ, Wietecha LA, Dennehy EB, et al. Phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of lasmiditan for acute treatment of migraine. Brain. 2019; Jul 1142(7):1894–1904.

- Krege JH, Rizzoli PB, Liffick E, et al. Safety findings from phase 3 lasmiditan studies for acute treatment of migraine: results from SAMURAI and SPARTAN. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(8):957–966.

- Tepper SJ, Vasudeva R, Krege JH, et al. Evaluation of 2-hour post-dose efficacy of lasmiditan for the acute treatment of difficult-to-Treat migraine attacks. Headache. 2020;60(8):1601–1615.

- Garnett T, Fitzgerald J. Four ways drug companies can ease racial disparities Politico2020. Available from: https://www.politico.com/news/agenda/2020/07/20/drug-companies-coronavirus-racial-disparities-372277.

- Woods-Burnham L, Johnson JR, Hooker SE, et al. The role of diverse populations in US clinical trials. Med. 2021;2(1):21–24.

- IHS. ICHD-II classification: parts 1–3: primary, secondary and other. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(1_suppl):23–136.

- IHS. The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629–808.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials. Washington: Office of Minority Health; 2016.

- Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25):2935–2959.

- Shapiro RE, Hochstetler HM, Dennehy EB, et al. Lasmiditan for acute treatment of migraine in patients with cardiovascular risk factors: post-hoc analysis of pooled results from 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):90.

- Tfelt-Hansen P, Pascual J, Ramadan N, et al. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine: third edition. A guide for investigators. Cephalalgia. 2012;32(1):6–38.

- Ashina M, Vasudeva R, Jin L, et al. Onset of efficacy following oral treatment with lasmiditan for the acute treatment of migraine: integrated results from 2 randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical studies. Headache. 2019;59(10):1788–1801.

- Charleston L. Headache disparities in African-Americans in the United States: a narrative review. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113(2):223–229.

- Charleston L, Spears RC, Flippen C, 2nd. Equity of African American men in headache in the United States: a perspective from African American headache medicine specialists (part 1). Headache. 2020;60(10):2473–2485.

- Ortega AN, Roby DH. Ending structural racism in the US health care system to eliminate health care inequities. JAMA. 2021;326(7):613–615.

- Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works - racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):768–773.

- Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Brindle P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2099.

- Mahmoud AN, Mentias A, Elgendy AY, et al. Migraine and the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events: a Meta-analysis of 16 cohort studies including 1 152 407 subjects. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e020498.

- Kurth T, Gaziano JM, Cook NR, et al. Migraine and risk of cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA. 2006;296(3):283–291.

- Kurth T, Winter AC, Eliassen AH, et al. Migraine and risk of cardiovascular disease in women: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2016;353:i2610.

- Becker C, Brobert GP, Almqvist PM, et al. Migraine and the risk of stroke, TIA, or death in the UK (CME). Headache. 2007;47(10):1374–1384.

- Sacco S, Ornello R, Ripa P, et al. Migraine and risk of ischaemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22(6):1001–1011.

- Peng KP, Chen YT, Fuh JL, et al. Migraine and incidence of ischemic stroke: a nationwide population-based study. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(4):327–335.

- Adelborg K, Szépligeti SK, Holland-Bill L, et al. Migraine and risk of cardiovascular diseases: Danish population based matched cohort study. BMJ. 2018;360:k96.

- Buse DC, Reed ML, Fanning KM, et al. Cardiovascular events, conditions, and procedures among people with episodic migraine in the US population: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Headache. 2017;57(1):31–44.

- Rubio-Beltran E, Labastida-Ramirez A, Van den Bogaerdt A, et al., editors. In vitro characterization of agonist binding and functional activity at a panel of serotonin receptor subtypes for lasmiditan, triptans and other 5-HT receptor ligands and activity relationships for contraction of human isolated coronary artery. Cephalalgia. 2017;37:363.

- Beltran ER, Kristian H, Labastida A, et al., editors. Lasmiditan and sumatriptan: comparison of in vivo vascular constriction in the dog and in vitro contraction of human arteries. Cephalalgia. 2016;36:104–105.

- James SA. John Henryism and the health of African-Americans. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1994;18(2):163–182.

- Foley KA, Cady R, Martin V, et al. Treating early versus treating mild: timing of migraine prescription medications among patients with diagnosed migraine. Headache. 2005;45(5):538–545.

- Golden W, Evans JK, Hu H. Migraine strikes study: factors in patients’ decision to treat early. J Headache Pain. 2009;10(2):93–99.

- Knievel K, Buchanan AS, Lombard L, et al. Lasmiditan for the acute treatment of migraine: Subgroup analyses by prior response to triptans. Cephalalgia. 2020;40(1):19–27.

- Loo LS, Ailani J, Schim J, et al. Efficacy and safety of lasmiditan in patients using concomitant migraine preventive medications: findings from SAMURAI and SPARTAN, two randomized phase 3 trials. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):84.

- Tfelt-Hansen P, Block G, Dahlöf C, et al. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine: second edition. Cephalalgia. 2000;20(9):765–786.

- Friesen P, Blease C. Placebo effects and racial and ethnic health disparities: an unjust and underexplored connection. J Med Ethics. 2018;44(11):774–781.

- Tuttle AH, Tohyama S, Ramsay T, et al. Increasing placebo responses over time in U.S. clinical trials of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2015;156(12):2616–2626.

- Milani SA, Swain M, Otufowora A, et al. Willingness to participate in health research among community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults: does race/ethnicity matter? J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(3):773–782.

- Tuckson RV. The disease of distrust. Science. 2020;370(6518):745.