Abstract

Background

Cough is one of the most common health issues for which medical attention is sought. A chronic cough (CC) is understood as a cough that lasts longer than 8 weeks. CC encompasses two subsets referred to as refractory chronic cough (RCC) and unexplained chronic cough (UCC). This study aims to assess the current understanding and perceptions of a RCC and UCC, from a physician’s perspective in Switzerland and how this understanding and practical work leads to the relevant diagnosis and treatment.

Methods

In October 2020, 549 GPs and 338 pulmonologists in Switzerland, received an invite to participate in the online-based quantitative survey. Data collection was carried out through a 25-minute online survey. The questionnaire was based on structured questions, and conducted on a randomized sample of doctors (general practitioners -GPs and pulmonologists) in the German- and French-speaking part of Switzerland.

Results

Overall, 33 pulmonologists and 52 GPs participated in the online survey. Only 39% of GPs, but 73% of pulmonologists, defined chronic cough as a cough lasting 8 weeks or longer. The majority of physicians (72%), especially pulmonologists (88%), perceived a clinical gap regarding the treatment of persistent cough. 74% of the sampled physicians agreed that persistent cough is a high burden of disease for patients. Based on the answers, the annual number of new patients with RCC and UCC in Switzerland is estimated at 9322 patients.

Conclusions

Results of this study have highlighted differences in the terminology used to describe CC (RCC and UCC), in the diagnostic tests used and, in the treatments used between GPs and pulmonologists. These findings suggest the need to align the current language regarding the disease to facilitate a standardized approach for diagnosis and treatment and towards improving patient care and reduce burden of disease for CC (RCC and UCC) patients.

Introduction

A chronic cough is one of the most common health issues for which medical attention is soughtCitation1. In a systematic review and a meta-analysis conducted by Song et al., the global prevalence of a chronic cough was estimated at around 9.6%Citation2. Sapaldia study for Switzerland showed a prevalence of chronic cough in current smoker as 9.2%, and in never smokers as 3.3%Citation3. Current guidelines define chronic cough as a cough, which lasts longer than 8 weeks in adults and 4 weeks in childrenCitation4. Chronic cough can manifest itself in different ways, often disrupting patients in their everyday lives, resulting in a cough with varying frequencies. Such varying frequencies make the definitions difficult that are based on temporal scales.

Likewise, the varied aetiology of a chronic cough can further complicate defining the condition, diagnosing patients and treating them appropriately. In more than 80% of the cases, one of the following underlying causes may be present, as associated conditions: upper airway cough syndrome (UACS), bronchial asthma or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)Citation5,Citation6. Other causes of chronic cough can include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, lung cancers, drug induced (e.g. ACE inhibitors), and cigarette smokingCitation4. It is vital to understand the process of diagnosis and treatment, so that patients can be managed and treated according to their specific condition.

Refractory chronic cough (RCC) and unexplained chronic cough (UCC) are subsets of chronic cough.

RCC is characterised by a persisting cough despite thorough investigation and adequate treatment for the diagnosed underlying condition, according to published practice guidelinesCitation4. Previous literature has used idiopathic chronic cough and unexplained chronic cough (UCC) interchangeably to describe another particular form of chronic cough, for which no underlying condition has been identifiedCitation7. Diagnosis of UCC requires that all other etiologies are excluded, and refers to the circumstance in which no diagnosable cause for cough has been found (despite extensive assessment for common and uncommon causes)Citation6,Citation8. Although both RCC and UCC present a CC, the difference between both lies in the diagnosis and the adequate treatment.

A study, looking at the diagnosis and treatment of RCC and UCC from the perspective of the patient, found that only 30% of the subjects felt that “their doctor had dealt with their cough thoroughly” and the medication was judged as having limited (57%) or no effect (36%)Citation9. The results of the two mentioned studies are significant enough to warrant further investigation into the perspective and practice of physicians in the diagnosis of RCC and UCC, also as some of the treatments used may have a higher risk of adverse events, and carry a safety riskCitation4. Specifically for UCC, P2X3 antagonists could be the new first treatment option; for RCC, P2X3 could be a solution if prior treatment was unsuccessfulCitation10.

The aim of this study was to describe and understand the knowledge, attitudes and perception of chronic cough, particularly RCC and UCC, from a physician’s perspective in Switzerland. In addition, it aimed to investigate the physician’s professional perspective on the extent to which RCC and UCC can affect the patient’s quality of life, as well as to estimate the incidence of RCC and UCC in Switzerland. GPs and pulmonologists were chosen to participate in this research, because chronic cough is predominantly managed in the primary care setting during the initial stages and by specialists in later stages, making both groups of physicians relevant to the study. The findings of this study are focused on exploring and describing clinical practice and highlight that there is a lot of discrepancy in the management of these CC patients, without prior hypothesis on finding gaps in treatment practice. Gaps in the diagnosis and treatment were also highlighted by the study by Slovarp who investigated the length of time and the number of physicians affected patients consult before receiving a diagnosis of and appropriate treatment for chronic coughCitation11.

Methods

Selection and description of participants

Participants were recruited by QualiproCitation12, using their existing database of registered physicians in Switzerland. The survey included participants from the German and French-speaking regions of Switzerland. Eligible participants for the survey were identified through a screening questionnaire at the beginning of the survey. To ensure respondents had sufficient knowledge and experience in managing patients with chronic cough, the screener only allowed participants to proceed to the survey stage if they had 2 years of specialist experience as a pulmonologist or 5 years of experience as a GP (i.e. the participant provided non-specialist medical assistance in primary care settings) and had seen a minimum of 5 adult patients with chronic cough in the past 3 months.

In October 2020, 549 GPs and 100% of registered pulmonologists (n = 338) in Switzerland, received an invite to participate in an online-based quantitative questionnaire study. The first 85 physicians who completed the screening questions and passed the screening criteria were considered for inclusion; it was the maximum sample size with the available resources. Overall response rate was 9.5%. Physicians who participated gave their informed consent to collect and use their data.

Data collection

In a preliminary step, 4 GPs and 4 pulmonologists were interviewed by telephone using a qualitative discussion guide. The qualitative interviews covered questions on knowledge, experience, and perception of CC in general and RCC and UCC in particular, as well as patient characteristics and perceived patient quality of life impairment. The aim of the qualitative interviews was to use the information collected to validate the questionnaire for the quantitative online survey.

Data collection was carried out through a 25-minute online questionnaire. This was conducted on a randomized, layered sample of doctors (GPs and pulmonologists) in the German- and French-speaking part of Switzerland. The questionnaire concerned adult patients and consisted of exclusively closed-type questions or statements, on which the level of agreement was measured using a 5-point Likert scale.

Estimated number of new patients with RCC and UCC in Switzerland

The online questionnaire inquired about the number of patients with CC visiting the physician, as well as their status (new or retreated), and the estimated share of RCC and UCC patients among all CC. Based on the responses from only pulmonologists, we have estimated the number of new patients per year with RCC and UCC in our sample and extrapolated to the total population in Switzerland by considering the total number of pulmonologists in the countryCitation13 We did not take into consideration the number of patients of the GPs because the size of the GPs sample was not representative of the GPs in the country.

The survey was designed to be exploratory, therefore, no formal hypothesis was set. Answers obtained are shown as descriptive information in the results. The varying perspectives of GPs and pulmonologists, as present in their answers were compared and noted as observations in the study.

Results

Characteristics of study population

Baseline characteristics of the study participants are presented in . Overall, 33 pulmonologists and 52 GPs participated in the online questionnaire.

Table 1. Response and background characteristics.

Terminology used and associated conditions in chronic cough

This study examined how physicians tend to define and understand the cough of patients. In total, 37% of GPs suggested they “sometimes/often” diagnose patients with chronic cough without underlying pathology (i.e. patients in which no underlying condition has been found despite thorough testing, and in which the cough is persistent) compared to 54% of pulmonologists ().

Table 2. Frequency of underlying diseases in patients with CC.

To understand respondents’ awareness of the definition of “chronic cough,” participant physicians were asked to indicate when they use the term “chronic cough” for a diagnosis in a patient with a cough based on five possible answer options. Overall, 52% of participants mentioned, that chronic cough is defined as a cough lasting over 8 weeks, a figure driven by 73% of pulmonologists (). However, only 39% of GPs defined chronic cough as a cough lasting 8 weeks or longer.

Table 3. Physicians’ definition of “chronic cough.”

Participants used different terms to define a chronic cough that persists after treatment of underlying causes. A larger number of GPs referred to this cough as: “chronic persistent cough” (69%) and “idiopathic cough” (52%). Pulmonologists preferred the terms “refractory chronic cough” (55%), “chronic persistent cough” (45%) and “cough hypersensitivity syndrome” (45%) (). Similarly, a cough without an identified underlying condition, despite thorough investigation (i.e. UCC), is most often referred by GPs as “chronic persistent cough” (62%) and “idiopathic cough” (62%), while pulmonologists tend to refer to it as “unexplained chronic cough” (58%) and “cough hypersensitivity syndrome” (48%) ().

Table 4. Terms used for CC patients where cough is persistent even after treatment of a potential underlying cause.

Table 5. Terms used for CC patients where no underlying condition has been found, despite thorough investigation (UCC).

This study also found that 76% of pulmonologists follow clinical guidelines for management and treatment of CC, compared to only 44% of GPs. In particular, GPs expressed uncertainty about the guidelines that should best be consulted. The GOLD/GINA guidelines for Asthma, COPD and COPD Overlap SyndromeCitation14 was the only guideline spontaneously mentioned by GPs, and followed by 13% of GPs. The other GPs relied on medical magazines, collaborations with specialists, and clinical directives. On the other hand, pulmonologists consulted the ERS (European Respiratory Society) guidelines (48%) and the DGP (German Respiratory Society) guidelines (24%).

Diagnosis and treatment for RCC and UCC

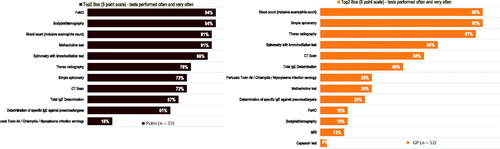

90% of GPs reported performing often/very-often a blood count or a simple spirometry to a new patient with CC symptoms; 87% and 65% of GPs reported performing a thorax radiography and a spirometry with bronchodilation test respectively (). On the other hand, 94% of pulmonologists reported performing often/very-often a FeNO testing and also a body plethysmography; 91% mentioned performing also a blood count (inclusive eosinophile count) or a methacholine test. No questions were asked on how physicians ruled out potentially underlying causes such as GERD.

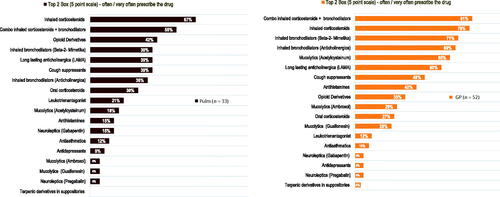

81% of GPs reported to prescribe often/very-often for the treatment of persistent cough a combination of inhaled corticosteroids and bronchodilators; 79% prescribed inhaled corticosteroids and 71% prescribed inhaled bronchodilators (). On the other hand, 67% of pulmonologists prescribed often/very-often inhaled corticosteroids, 55% prescribed often/very-often a combination of inhaled corticosteroids and bronchodilators, and 42% prescribed opioids and their derivatives, such as codeine (). The majority of physicians (72%), especially pulmonologists (88%), perceived a clinical gap regarding the treatment of persistent cough. 79% of pulmonologists, as well as 62% of GPs, suggest that there is a need for new innovative drugs when it comes to the treatment of RCC and UCC.

Figure 2. Treatments prescribed (often and very often) for chronic cough not related to any underlying condition.

On average, pulmonologists reported seeing in average 191 patients per month, 128 patients presented with a respiratory condition, of which in average 56 had cough and 32 showed to have a CC. GPs reported receiving in average 285 patients each month, in average 59 had respiratory conditions, of which 43 presented a cough and 17 had CC.

Estimated number of new patients with RCC and UCC

On average, pulmonologists reported that among the 32 patients with CC, 54% were new in average per month, and 44% were retreated. Subsequently, over one year, one pulmonologist could approximately see 207 new patients with CC ((32 × 54%) × 12 = 207.36) (). Considering that there are 338 registered pulmonologists in the country, then we inferred that there could be approximately 70,088 patients with CC in the country over one year (207.36 × 338 = 70,088)Citation11. Finally, pulmonologists reported that on average 13.3% of the CC patients develop RCC and UCC. Hence, the estimated number of new patients with persistent cough – RCC and UCC- in Switzerland seems to be 9322 per year (70,088 × 13.3% = 9322) ().

Table 6. Estimated number of new patients with RCC and UCC in Switzerland. Detailed factors used for the estimation of incidence of RCC and UCC.

Burden of disease and clinical care gaps

Pulmonologists and GPs reported about the impact of a persisting cough on the social, emotional and physical wellbeing of patients. 74% of the sampled physicians agreed that persistent cough is in general a high burden of disease for patients. More specifically, the impact of a persistent cough was classed as very high in social life, emotional sphere and work activity by more than 70% of pulmonologists. About three quarters of physicians perceived that persistent cough affects patients’ quality of life as much as asthma and migraine.

Discussion

This study, based on a standard questionnaire to GPs and pulmonologists, explored the understanding and perception of physicians about diagnosis, treatment, and burden of disease of chronic cough, particularly RCC and UCC. Results of this study have highlighted very relevant differences and gaps for the diagnosis and treatment of RCC and UCC between GPs and pulmonologists.

The physician’s opinion on the definition for chronic cough vary. While there seems to be a consensus about the correct definition of chronic cough among the majority (73%) of pulmonologists, most GPs (61%) are apparently not aware that a cough is classified as chronic once it lasts for more than 8 weeks. Comparable results were found in a similar study in SpainCitation15. GPs are more likely to consider CC as a symptom of a different underlying disease, compared to pulmonologists who consider CC as a standalone disease. Recognizing CC, including RCC and UCC, as a distinct disease is important to induce more harmony in diagnosis, treatment, reducing diagnosis delay, and improve patient care and reduce the length of burden of diseaseCitation6.

There is a clear lack of consensus amongst physicians regarding terminology for a cough that persists despite treatment of potential underlying causes or without an underlying condition. While most GPs (69%) refer to it as “Chronic Persistent Cough,” over half (55%) of pulmonologists prefer to use the term “Chronic Refractory Cough.” Most GPs (62%) state they refer to chronic cough without an underlying condition as “chronic persistent cough” or “idiopathic” cough, whereas most pulmonologists (58%) claim to use the term “unexplained cough.” Our findings are in line with McGarvey et al. (2019) who have explained the variety in the terminology and the difficulties that this generates for patient careCitation6. These findings suggest the need to align the current language regarding the disease to facilitate a standardized approach towards improving patient care. As shown in our results and in line with McGarvey, the term I(diopathic)CC is still used by physicians, however, a cough that remains unresolved after a thorough diagnostic and treatment approach might be the preferable and more accurately referred to as UCC. Furthermore, despite the term “cough hypersensitivity syndrome” is still be used by 33% of GPs in our sample and 45% of pulmonologists in our sample, literature suggests it does not adequately define the coughCitation16.

Most frequently performed tests on new patients presenting with chronic cough symptoms vary slightly between GPs and pulmonologists: The vast majority of GPs report doing a blood count, simple spirometry and thorax radiography, whilst almost all pulmonologists report they often perform FeNO testing and also a body plethysmography. These tests are also recommended by and consistent with ERS and Chest guidelines. These results differ slightly from the study in Spain, where GPs and pulmonologists use mostly chest x-ray, and do not use blood countCitation17. Although FeNO testing seems to be widely used in Switzerland, it is worth noting that its clinical usefulness for the diagnosis of chronic cough has not yet been systematically investigatedCitation18.

Inhaled corticosteroids, either given alone or in combination with bronchodilators are reported as the most frequently prescribed treatments for chronic cough that is not related to any underlying condition; similar treatment patterns are followed also in SpainCitation19. Opioid derivates, such as codein, are more often prescribed by pulmonologists compared with GPs. According to pulmonologists, opioid derivates are the most effective option for treating this kind of cough, whereas GPs perceive inhaled corticosteroids, either alone or in combination with bronchodilators, as the most effective option. Conversely, the Spanish study found little use of opioid derivatives despite their perceived effectiveness probably due to the safety profile. But, evidence supporting most currently recommended treatments is still limited or weak, as some of these are still experimental and can produce adverse events, as a recent review summarizesCitation19.

Indeed, our study revealed that the majority of physicians perceived there is a clinical gap in terms of effective and specific treatments of RCC and UCC, especially pulmonologists. The increased understanding of the pathways of cough and of the abnormalities underlying RCC and UCC has made possible to develop innovative drugs that block these pathways, such as sodium channel blockersCitation20, transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 antagonists (TRPV1)Citation21, and P2X3 receptor antagonistsCitation22; the latter showing better impact on RCC and UCC.

Almost all interviewed physicians in Switzerland agree that the burden of disease for patients with persistent cough is high. About three quarters of physicians perceive that persistent cough affects patients’ quality of life as much as asthma and migraine. These perceptions of physicians interviewed confirm recent studies showing that patients with CC, RCC and UCC report many physical and psychological effects, which prolongs burden of disease and further impairs their quality of life; in addition, it poses a significant economic burden for the patient and healthcare systemsCitation12.

The multifactorial nature of a chronic cough, as well as the varying professional perspective and therapeutic outcomes has generally resulted in discrepancies on the estimated incidence and prevalence in the general population. The prevalence of chronic cough in published literature is estimated to be approximately 10% globally, with regional variations providing an estimate of 12.7% of total population in Europe, and a recent study in Austria showing 9%Citation2,Citation23,Citation24. Estimation of incidence of chronic cough is scarcer. A recent Canadian study, estimated that incidence of CC in Canada is 3.58–5.70 per 100 person-years; whereas in the Rotterdam study incidence is estimated at 1.6 per 100 person-yearsCitation23,Citation25. The estimation of the prevalence and incidence of the smaller sub-group of persisting cough, such as RCC and UCC, is more difficult to assess. Our study allowed to estimate the number of newly diagnosed patients of RCC and UCC in Switzerland. Our results show an estimated number of new patients of RCC and UCC of 9322 patients annually. We recognize that our estimate might be an underestimation because it focuses on the answers of only pulmonologists.

The diversity in the criteria used could result in different levels of care offered to patients across the territory. The results of this study showed that 6% and 16% of total patients received by GP and pulmonologist respectively are CC patients. For GPs it is still a high percentage of attended patients, when considering that the prevalence of asthma in adult population is 5%. Common language, diagnosis and treatment criteria among GPs and pulmonologists will help improve the burden of disease of an important share of the population and the personal needs of the patient.

Our study is subject to the limitations of a survey. First, given the methodology of recruitment, the survey may have been completed by those physicians that were more interested in CC, and not necessarily to the universe of GPs and pulmonologists in Switzerland. The survey participation of GPs was lower than the number of pulmonologists who participated, therefore, data may be biased in favour of the pulmonologists, who are better represented in the study’s sample. Although participants declared a minimum of CC patients, their answers could not be representative of other colleagues. Any future studies should increase the sample of GPs and should include participants from the Italian speaking part of Switzerland, this will allow to be more representative of the cultural makeup of the country. Secondly, as the study partially focused on the use of the physician’s language in diagnosing and treating a RCC and UCC, it gained an important insight into how the physician’s mother tongue may influence their professional language use. Third, this study is based on physician’s perceptions and opinions (i.e. stated preferences), as opposed to a systematic analysis of patient record forms or chart review, so there was no data source verification. Any future studies may include both the physician’s correlation and patient record forms/chart reviews to note any correlations, as well as exploring the reason behind the lack of alignment amongst physicians. This implies also that the study findings are relevant only to this cohort. Fourth, the study is subject to the inherent weaknesses of a cross-sectional analysis at a specific point in time, besides sampling errors could have affected the precision and interpretation of the results, and it does not allow an interpretation of developments or trends over time. Finally, the questionnaire used for the survey study was not a validated questionnaire.

Conclusion

Chronic Cough is one of the most common health related reasons to seek for medical attention. However, in Switzerland little is known about how physicians manage, diagnose and treat CC, RCC and UCC, their perceptions on patients’ quality of life, and about the quantity of patients suffering from these conditions. This research, based on a selected sample of physicians in the French and German-speaking parts of Switzerland, reports differences in the terminology used to describe CC (RCC and UCC), in the diagnostic tests used and, in the treatments used between GPs and pulmonologists. The differences observed likely originate from the lack of scientific evidence or clear standardized protocols to diagnose and treat chronic cough. Results indicate the need to homogenize the language, diagnostic and treatment criteria among different physicians regarding RCC and UCC in order to improve the care for CC patients. National and international guidelines should be uniform to guide physicians treating RCC and UCC. This effort is likely to support earlier diagnosis for patients and therefore reduce burden of disease.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by MSD Merck Sharp & Dohme AG Switzerland.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

PG, DK and AFB are employees of MSD Merck Sharp & Dohme AG Switzerland. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests. External experts Prof. Leuppi and Prof. Zeller have consulting contracts with MSD Switzerland. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

Patrik Guggisberg was involved in designing the study, interpreting the data and in writing the manuscript. Daniel Koch was involved in designing the study, collecting and analysing the data and in writing the manuscript. Andrea Favre-Bulle was involved in writing the manuscript. Matteo Fabiani was involved in interpreting the data and writing the manuscript. Sabina Heinz was involved in interpreting the data and writing the manuscript. Prof. Dr. Med Jörg Leuppi was involved in interpreting and writing and the manuscript. Prof. Dr. Med. Andreas Zeller was involved in interpreting and writing.

Ethics statement

The ethical committee was consulted but their review and approval were not required in accordance with the local legislation (Swiss federal law on research on humansCitation26. Participating physicians had to give their informed consent before filling out the online questionnaire (see additional file 1).

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank all physicians for participating in our survey study. We would also like to acknowledge Mrs. Zahra Pasha’s assistance in writing the article.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Mahashur A. Chronic dry cough: diagnostic and management approaches. Lung India. 2015;32(1):44–49.

- Song WJ, Chang YS, Faruqi S, et al. The global epidemiology of chronic cough in adults: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(5):1479–1481.

- Zemp E, Elsasser S, Schindler C, et al. Long-term ambient air pollution and respiratory symptoms in adults (SAPALDIA study). The SAPALDIA TeamAm J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(4 Pt 1):1257–1266.

- Morice AH, Millqvist E, Bieksiene K, et al. ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(1):1901136.

- Kaplan AG. Chronic cough in adults: make the diagnosis and make a difference. Pulm Ther. 2019;5(1):11–21.

- Mello CJ, Irwin RS, Curley FJ. Predictive values of the character, timing, and complications of chronic cough in diagnosing its cause. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(9):997–1003.

- McGarvey L, Gibson PG. What is chronic cough? Terminology. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(6):1711–1714.

- Iyer VN, Lim KG. Chronic cough: an update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(10):1115–1126.

- Chamberlain SA, Garrod R, Douiri A, et al. The impact of chronic cough: a cross-sectional European survey. Lung. 2015;193(3):401–408.

- McGarvey LP, Birring SS, Morice AH, et al. Efficacy and safety of gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist, in refractory chronic cough and unexplained chronic cough (COUGH-1 and COUGH-2): results from two double-blind, randomised, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. The Lancet. 2022;399(10328):909–923.

- Slovarp L, Loomis BK, Glaspey A. Assessing referral and practice patterns of patients with chronic cough referred for behavioral cough suppression therapy. Chron Respir Dis. 2018;15(3):296–305.

- QualiPro. 2020; [cited 2021 March]. Available from: https://qualipro.ch/index.html.

- FMH Ärztestatistik, 2020. https://www.fmh.ch/themen/aerztestatistik/fmh-aerztestatistik.cfm.

- GOLD/GINA, Diagnosis of diseases of chronic airflow limitation: Asthma, COPD and Asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS), 2015.Available from: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/GOLD_ACOS_2015.pdf.

- Dominguez-Ortega J, Molina París J, Trigueros JA, et al. Use of clinical guidelines and protocols for the management of chronic cough by Spanish physicians and its influence on the diagnosis of chronic cough. Allergy. 2021;76(Suppl. 110):583–637 ABSTRACT 691.

- Morice AH, Millqvist E, Belvisi MG, et al. Expert opinion on the cough hypersensitivity syndrome in respiratory medicine. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(5):1132–1148.

- Maestu P, et al. A survey of physicians’ perception of the use and effectiveness of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in chronic cough patients. Lung. 2021; 199:507–515.

- Sadeghi MH, Wright CE, Hart S, et al. Phenotyping patients with chronic cough: evaluating the ability to predict the response to anti-inflammatory therapy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(3):285–291.

- Morice A, Dicpinigaitis P, McGarvey L, et al. Chronic cough: new insights and future prospects. Eur Respir Rev. 2021;30(162):210127.

- Smith JA, McGarvey LPA, Badri H, et al. Effects of a novel sodium channel blocker, GSK2339345, in patients with refractory chronic cough. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;55(9):712–719.

- Belvisi MG, Birrell MA, Wortley MA, et al. XEN-D0501, a novel transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 antagonist, does not reduce cough in patients with refractory cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(10):1255–1263.

- Muccino D, Green S. Update on the clinical development of gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist for the treatment of refractory chronic cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2019;56:75–78.

- Arinze J, de Roos E, Karimi L, et al. Prevalence and incidence of, and risk factors for chronic cough in the adult population: the Rotterdam study. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(2):00300–2019.

- Abozid H, Baxter CA, Hartl S, et al. Distribution of chronic cough phenotypes in the general population: a cross-sectional analysis of the LEAD cohort in Austria. Respir Med. 2022;192:106726.

- Satia I, Mayhew AJ, Sohel N, et al. Prevalence, incidence and characteristics of chronic cough among adults from the Canadian longitudinal study on aging. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7(2):00160-2021.

- Swiss Confederation, 2013. Federal law concerning the research of human beings (Human Law LRUm – RU 2013 3215); [cited 2021 May 20]. Available from: https://www.admin.ch/opc/de/official-compilation/2013/3215.pdf.