Abstract

Objective

This real-world study evaluated biologic treatment patterns in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis (UC).

Methods

IQVIA PharMetrics, IBM MarketScan, and Optum Clinformatics were pooled to identify UC patients with ≥1 claim for UC and ≥1 claim for adalimumab (ADA), golimumab (GOL), infliximab (IFX), or vedolizumab (VDZ). The index date for each biologic was the first claim for that biologic. Patients could be included in >1 cohort if they switched biologics during the identification period. Continuous eligibility for medical/pharmacy benefits was required for 12 months before (baseline) and after (follow-up) the index date. Patients lacking claims for any biologic during baseline were categorized as bio-naïve; those with any biologic claim were categorized as bio-experienced. Persistence was defined as the proportion of patients that remained on the index biologic without a gap between claims of >28 days for ADA, >56 days for GOL, and >112 days for IFX and VDZ. Dose titration was assessed among patients with ≥2 maintenance doses during follow-up among ADA, GOL, and VDZ patients.

Results

In total, 6,106 bio-naïve UC patients and 1,027 bio-experienced UC patients were identified. Patients treated with VDZ and IFX had the highest persistence followed by ADA and GOL patients for bio-naïve and bio-experienced, respectively. ADA patients had a numerically higher proportion of patients with 50% dose escalation, followed by VDZ and GOL; 50% dose reduction was observed in ≤1% patients.

Conclusions

In this descriptive study of UC patients without confounder adjustment, VDZ persistence was numerically highest followed by IFX, GOL, and ADA across both populations.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic, idiopathic disorder characterized by inflammation and ulcerations of the colonic mucosaCitation1. In addition to bloody diarrhea, urgency, and abdominal pain, patients may also experience manifestations of extraintestinal inflammation involving the eyes, joints, skin, and liverCitation2. UC and Crohn’s disease (CD), collectively referred to as inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), are characterized by a dysregulated immune response to commensal gut organisms in genetically susceptible individualsCitation2. The main goals of UC management are the induction and maintenance of clinical and endoscopic remissionCitation3,Citation4. Control of the inflammation not only re-establishes quality-of-life but also prevents complications (such as anemia, excess use of corticosteroids, thromboembolism, and colorectal cancer), hospitalizations, and colectomyCitation5. Treatment options for UC include mesalamine (oral and rectal formulations); corticosteroids (systemic and rectal); thiopurines; anti-tumor necrosis factor α (anti-TNFα) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) (adalimumab [ADA; Abbvie], golimumab [GOL; Janssen Biotech, Inc.], infliximab [IFX; Janssen Biotech, Inc.]); vedolizumab (VDZ; Takeda), a mAb directed against the integrin α4β7; ustekinumab, a mAb antibody that targets interleukin-12 and interleukin-23; and tofacitinib, a JAK inhibitorCitation6. Unfortunately, medical therapies are not uniformly effective. A particular challenge with mAbs is their pharmacokinetic variability due to many factors including the inflammatory burden and the development of anti-drug antibodiesCitation7. As a result, a significant proportion of initial responders lose response and require dose escalation or a switch in therapy. The high rates of dose escalation and loss of response limit the cost-effectiveness of biologics therapiesCitation8.

Examining biologic persistence, adherence, and dose titration in patients with UC provides insight into their effectiveness in real-world use and may help inform treatment decisions and initiatives focused on quality improvement. Most studies to date have not evaluated bio-naïve and bio-experienced patients separately, perhaps due to the small sample size for products such as GOL and VDZCitation9–13. In light of this, this study examined patients with UC treated with ADA, GOL, IFX, and VDZ with an emphasis on stratifying results among bio-naïve and bio-experienced patients in three large US commercial databases.

Methods

Data sources

This retrospective observational study used data from the IBM MarketScan (IBM; January 1, 2014–September 30, 2018), Optum Clinformatics Data Mart (Optum; January 1, 2014–March 31, 2019), and IQVIA PharMetrics Plus (IQVIA; January 1, 2014–December 31, 2018) databases. These databases contain medical and pharmacy claims for commercial populations in the US and are generally representative of the US population with employer-provided healthcare insurance. The medical claims were coded using either the International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), ICD-10-CM (10th revision, implemented on October 1, 2015), or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes; the pharmacy claims were coded using National Drug Code (NDC) or Health Care Common Procedure Coding Systems (HCPCS). All databases used were independent and contained no personally identifiable information.

Patient selection

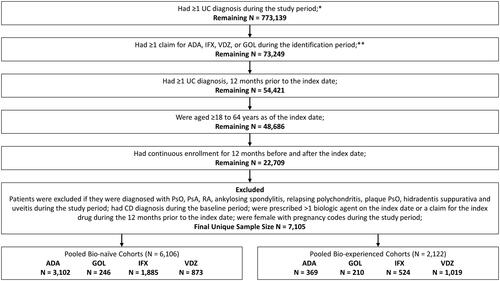

Adult patients (≥18 years) with ≥1 medical or pharmacy claim for ADA, GOL, IFX, or VDZ between January 1, 2015 to the end of the identification period (Optum: March 31, 2018, IQVIA: December 31, 2017; IBM: September 30, 2017) were included in the study. The index date was defined as the date of the first medical or pharmacy claim for any biologic (“index biologic”) treatment during the identification period. Patients were required to have continuous health plan enrollment and medical and pharmacy benefits 12 months prior to (baseline period) and 12 months after (follow-up period) the index date. Patients were required to have ≥1 UC diagnosis (ICD-9-CM: code 556 or ICD-10-CM code K51) during the baseline period. Patients ≥65 years on index date or with Medicare as primary payer were excluded to limit the study population to patients with commercial insurance. Additional selection criteria are listed in .

Figure 1. Flow-chart for patient inclusion criteria. *IBM Study Period: January 1, 2014–September 30, 2018; Optum Study Period: January 1, 2014–March 31, 2019; IQVIA Study Period: January 1, 2014–December 31, 2018. **IBM Identification Period: January 1, 2015–September 30, 2017; Optum Identification Period: January 1, 2015–March 31, 2018; IQVIA Identification Period: January 1, 2015–December 31, 2017.

Patients were placed into one or more of the four biologic treatment cohorts (ADA, GOL, IFX, or VDZ) based on their biologic usage during the identification period. Ustekinumab and tofacitinib were not included in the study since they were not approved for the treatment of UC during either the identification or study period. For each treatment cohort, patients were further divided into bio-naïve and bio-experienced cohorts. UC patients were considered bio-naïve if they did not have a claim for any biologic (ADA, GOL, IFX, or VDZ) during the baseline period. All remaining patients were classified as bio-experienced and could be present in multiple bio-experienced cohorts based on all biologics they received during the identification period.

Study measures and statistical methods

During the baseline period, patients in each cohort were evaluated for baseline characteristics, such as age, sex, US geographic region, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, and baseline comorbidities.

Persistence was defined as the proportion of patients that remained on their index biologic without a gap of 28 days for ADA, 56 days for GOL, and 112 days for IFX and VDZ (based on two times the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA]-labeled frequency of the maintenance dose) between the “run-out date” (last date of days of supply) of the previous prescription and the start date of the next prescription. Patients that were not persistent were classified as discontinuers. The discontinuation date was defined as the run-out date of the last biologic except when a switch (administration of a non-index biologic) occurred. If a switch occurred before the run-out date, the switch date was the discontinuation date. Patients who discontinued a biologic were further classified into three groups: restarters were patients that restarted their index biologic after their discontinuation date; switchers were patients who had administration of a non-index biologic anytime during their follow-up period; all remaining patients that neither switched nor restarted their index biologic were classified as true discontinuers. Days of supply for each claim can be identified using NDC claims, which have a variable identifying days of supply, whereas HCPCS claims have no indication. Therefore, imputation for days of supply was performed using the gap between two biologic claims: if the gap between two claims was <38 days, then days of supply was assumed to be 30 days. If the gap between two claims was between 38 and 46 days, then 42 days was imputed as the days of supply. Finally, if the gap between two claims was >46 days, 56 days was imputed as the days of supply. Since the gap between two ADA claims was generally 30 days and only the quantity dispensed varyied, no imputation was conducted for ADA. Similarly for GOL, the two claims were generally 56–60 days apart and hence no imputation was conducted.

To evaluate the robustness of the findings, a fixed discontinuation gap of 90 days was used to evaluate persistence and discontinuation among bio-naïve and bio-experienced patients. It is most common to see a 30 day supply per claim for ADA claims. Therefore, a 60-day gap for ADA was used as another sensitivity analysis (two times the most common days supplied observed on claims).

Medication adherence was quantified by assessing the Medication Possession Ratio (MPR) which was defined as the sum of days of supply for either ADA, GOL, IFX, or VDZ divided by the total number of days in a 12-month follow-up period. Patients with MPR ≥0.8 were considered adherent.

Dose titration was classified as either dose escalation or dose reduction and was determined for any patient who had two or more maintenance doses in the follow-up period. The start of the maintenance period was defined based on FDA label (ADA: the claim must be the third claim and ≥22 days from the index date; GOL: the claim must be the third claim and ≥ 33 days from the index date; IFX & VDZ: the claim must be the fourth claim and ≥78 days from the index date). The overall average maintenance dose (including ± 20% variation around the dose per label) was calculated starting with the first maintenance dose and censoring at the earliest of discontinuation date (using a fixed 90-day gap) or end of follow-up. Patients with a mean maintenance dose ≥50% or ≥100% above the FDA-labeled maintenance dose were classified as ≥50% or ≥100% dose escalation, whereas patients with a mean maintenance dose ≥50% below the FDA-labeled maintenance dose were classified as ≥50% dose reduction. A 20% variation threshold definition was also used to identify mean maintenance doses within, above, or below the 20% allowable variation from the FDA-labeled maintenance dosing (FDA-labeled maintenance dosing for ADA: 40 mg/2 weeks, GOL: 100 mg/4 weeks, VDZ: 300 mg/8 weeks). Being within ±20% was considered within label while anything >20% above was considered dose escalation (ADA: >48 mg/2 weeks, GOL: >120 mg/4 weeks, VDZ: >360 mg/8 weeks thresholds for >20% dose escalation above label) and anything >20% below was considered dose reduction (ADA: <32 mg/2 weeks, GOL: <80 mg/4 weeks, VDZ: <240 mg/8 weeks thresholds for >20% dose reduction below label). Claims databases do not have information on the weight of the patient. Hence, IFX was excluded from the dose titration analyses as dosing is weight-dependent, complicating assessment of dose titration for the IFX cohort from claims data.

Descriptive analyses were conducted separately for the three data sources and patient populations were pooled to increase the sample size. All analyses were conducted in the pooled population. Means and standard deviations were provided for continuous variables, whereas counts of patients and percentages were provided for categorical variables.

Results

After applying the study inclusion and exclusion criteria, 6,106 patients were categorized as bio-naïve, and 2,122 patients were categorized as bio-experienced. Among the biologic cohorts, anti-TNF biologic cohorts (ADA, IFX, GOL) had a higher proportion of bio-naïve patients than bio-experienced patients [ADA (89.4% vs 10.6%), GOL (53.9% vs 46.1%), and IFX (78.2% vs 21.8%)], whereas VDZ had a lower proportion of bio-naïve patients (46.1% vs 53.9%), respectively (). The mean age of patients was consistent across bio-naïve and bio-experienced patients and ranged from approximately 39–41 years (). More than half of the patients were males (57–61%) residing in the south part of the country (38–50%) (). The mean CCI ranged between 0.6 and 0.8, with anemia the most frequently observed co-morbidity (ADA 26.5%, 25.5%; GOL 24.4%, 30.0%; IFX 34.7%, 35.9%; VDZ 27.1%, 31.5%; for bio-naïve and bio-experienced cohorts, respectively).

Table 1. Descriptive baseline characteristics for pooled bio-naïve and bio-experienced patients.

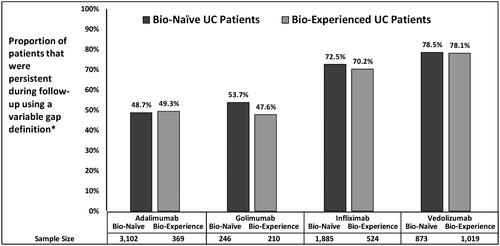

Using a variable gap definition, bio-naïve and bio-experienced patients exhibited similar persistence to treatment over the 12-months of follow-up across all four biologics (). Trends were generally similar across the three databases. Patients treated with VDZ (78.5%, 78.1%) and IFX (72.5%, 70.2%) had the highest persistence followed by ADA (48.7%, 49.3%) and GOL (53.7%, 47.6%) patients for bio-naïve and bio-experienced groups, respectively (). Among bio-experienced patients, discontinuation without restart or switch to another biologic was observed in 19.5% of patients on ADA, 26.7% of patients on GOL, 14.7% of patients on IFX, and 14.4% of patients on VDZ. In contrast, 18.2% of bio-naïve ADA patients, 22.0% of bio-naïve GOL patients, 11.4% of bio-naïve IFX patients, and 6.1% of bio-naïve VDZ patients discontinued and switched to another biologic. (). To check the robustness of these findings, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using a fixed gap definition of 90 days for all cohorts. As delineated in , similar trends for treatment patterns were observed when using the fixed gap, specifically the relative degree of persistence and discontinuation across the biologics. In addition, a separate sensitivity analysis using a 60-day gap was conducted for ADA since a higher proportion of ADA (∼16%) re-started their initial biologic using the variable gap definition. Using the 60-day gap definition, ∼59% patients treated with ADA were persistent to their treatment, ∼5% restarted ADA (their index biologic), and ∼19% patients discontinued without switching or restarting another biologic.

Figure 2. Unadjusted persistence rates among UC Patients during 12-month follow-up period using variable gap definition*. *Variable definition for ADA was 28 days; GOL was 56 days; IFX and VDZ was 112 days.

Table 2. Treatment patterns for pooled bio-naïve and bio-experienced patients.

During the 12-month follow-up period, the proportion of patients that were adherent (MPR ≥0.8) to their treatment was similar across bio-naïve and bio-experienced patients, with VDZ (64.4%, 71.8%) patients most adherent, followed by IFX (62.1%, 67.0%), ADA (57.5%, 57.7%), and GOL (52.4%, 45.2%; ). To evaluate dose titration, patients were required to have ≥2 maintenance doses during the follow-up period, and only ADA, GOL, and VDZ patients were included in the analysis (IFX was excluded from the dose titration analysis since dosing is weight-dependent, complicating assessment of dose titration). The final sample size for dose titration calculation was as follows: bio-naïve (ADA: 2599; GOL: 187; VDZ: 582) and bio-experienced (ADA: 217; GOL: 77; VDZ: 365) patients. During follow-up, bio-naïve patients had a relatively lower number of patients with ≥50% dose escalation than bio-experienced patients across ADA (13.0% vs 16.1%), VDZ (8.1% vs 9.9%), and GOL (1.6% vs 2.6%; ); a ≥50% dose reduction was observed in <1% of both bio-naïve and bio-experienced patients. When allowing for a 20% variation from US label maintenance dose, a similar trend was observed – a numerically lower proportion of bio-naïve patients had a dose escalation than bio-experienced patients across all cohorts (ADA: 19.1% vs 21.2%; GOL: 4.3% vs 6.5%; VDZ: 16.3% vs 20.0%). However, bio-naïve patients had a higher proportion of dose reduction relative to bio-experienced patients for GOL (9.5% vs 6.5%) and VDZ (3.3% vs 2.5%) based on the 20% variation threshold ().

Table 3. Dosing titration for pooled bio-naïve and bio-experienced patients.

Discussion

The retrospective claims-based analyses presented in this report provide a current summary of the real-world use of four commonly prescribed biologics for UC. Using three databases, we obtained large sample sizes to study biologic persistence, adherence, and dose titration of the biologics for the treatment of UC. Among UC bio-naïve patients treated with a biologic, more patients received ADA and IFX than VDZ and GOL, likely reflecting their position as more established treatments. In contrast, ADA and IFX were prescribed much less frequently among bio-experienced patients. Baseline characteristics, including mean age, age distribution, sex, geographic distribution, comorbidities, and CCI, were similar across all cohorts.

In the current analysis, the measurements of persistence and adherence generally showed comparable results in bio-naïve and bio-experienced cohorts. However, the four biologics differed in the degree to which patients persisted on their treatment regimen with infusion-based biologics (VDZ and IFX) showing numerically higher persistence (70–78%) than subcutaneous biologics that can be self-administered (ADA and GOL; 47–53%). Similar results have been reported in the literature – a retrospective study reported that only 57% of UC patients that initiated biologics (ADA, CZP, GOL, IFX, natalizumab) were persistent to their therapyCitation9. Another retrospective study that evaluated discontinuation among bio-naïve UC patients reported that 45% of IFX and 52% of ADA patients discontinued their index biologic within 12 months (translating into 55% and 48% persistence, respectively)Citation14. Smith et al.Citation16reported that 60.7% (56.9% for ADA, 63.8% for GOL, 64.8% for IFX, and 70.9% for VDZ) of patients were persistent after 1 year. In another study, Comerford et al.Citation15 reported similar persistence results for ADA, IFX, and VDZ, but slightly lower results for GOL (56.2% ADA, 44.1% GOL, 64.9% IFX, 69.4% VDZ).

Adherence to medication is an ongoing challenge while treating UC patients who frequently require long-term treatment to maintain remission. A single-center, retrospective cohort analysis of patients reported that 87% of UC patients on biologics were adherent to their therapy (MPR >0.86)Citation17. Another retrospective study using the MarketScan database reported that 61–69% of IBD patients that initiated treatment with IFX or VDZ were adherent to their treatmentCitation18. In the current study, adherence ranged between 57–72% and was largely similar for bio-naïve and bio-experienced patients treated with ADA, IFX, and VDZ, suggesting that adherence is minimally affected by line of therapy for these three biologics. The differences in adherence across studies could be attributed to differences in study design (intent to treat vs on treatment approach), data sources (singe center vs commercial databases), patient characteristics (UC vs IBD or mean age), different measures of adherence (MPR vs PDC), and the use of different thresholds to evaluate adherence (0.80 vs 0.86).

Since non-adherence to therapy is associated with an increased risk of relapse and cost of care, our findings reaffirm an ongoing need for improvement in adherence rates across the treatment options studied or for new treatments that may improve adherenceCitation19.

It bears emphasizing that adherence and persistence depend not only on the specific characteristics of the agent used (such as mode and frequency of administration and safety during pregnancy), but also on patient, provider and healthcare system factors as wellCitation20. The patient’s expectations on effectiveness, perception of safety and out-of-pocket costs must be considered when selecting therapy. Membership in an IBD patient organization is associated with better adherence. Adherence/persistence will be lower if the provider has selected an agent less likely to be effective in the specific patient, has not adequately explained risks and benefits of treatment, is unable to regularly monitor the patient for toxicity, or is unable to bear the administrative burden of prescribing biologicsCitation21,Citation22. Finally, several aspects of the health care system influence adherence, including availability of teaching for self-injecting patients and insurance policies on dose escalation.

Dose escalation has been reported as an indicator of suboptimal biologic therapy in UC patientsCitation7. In our analyses, bio-naïve patients had a relatively lower number of patients with ≥50% dose escalation than bio-experienced patients across ADA, VDZ, and GOL, whereas ≥50% dose reduction was observed in <1% of both bio-naïve and bio-experienced patients. Similar results were observed when a 20% variation from US label maintenance dose was evaluated – a lower proportion of bio-naïve patients had a dose escalation than bio-experienced patients across all cohorts, though dose reduction was slightly more common based on the >20% variation for US label threshold, ranging from 2.5 to 9.6% and was also slightly higher in bio-naïve patients. A similar relatively low rate of dose escalation for GOL-treated patients was observed in another study of administrative claims (9.9% had dose escalation by the 12-month post-index point)Citation16. Dose escalation within the first year was observed 3–4 times more frequently among patients treated with ADA (19–21%) and VDZ (16–20%). These levels are generally comparable to a recent literature review of four studies published in 2014–2017 that found 8–35% of patients experienced dose escalation of the index biologic in the first year, and an analysis of a 2005–2013 claims database that found 28% of UC patients receiving a first-line biologic required a dose escalation within 12 months and 40% within 24 months of follow-upCitation18.

More recent therapies such as ustekinumab and tofacitinib add treatments with new mechanisms of action for the treatment of patients with UC. So far real-world evidence for these two biologics in UC has been limited to registry, cohort, and single- and multicenter studiesCitation23–25. Future real-world studies are needed to evaluate biologic treatment patterns adjusted for potential confounders to inform clinical decisions in UC.

This study did not aim to make comparisons across bio-naïve and bio-experienced treatment groups. Rather, results for the two cohorts were presented separately for the purpose of understanding some of the inherent variability between patients in each group. As discussed in the Introduction section, these biologic therapies are not uniformly effective across patients, and a significant proportion of initial responders lose response and require dose escalation or a switch in therapy. This is a likely contributor to the large number of patients in the bio-naïve cohorts (relative to bio-experienced) for older biologic agents (ADA, IFX) that have been indicated for treating patients with UC for many years. In contrast, the most recently approved biologic for UC examined in our study (VDZ) had a larger number of patients that were bio-experienced relative to bio-naïve. This is not surprising given that newer agents are frequently used initially in patients that have failed prior therapies, particularly if they represent a new mechanism of action from older agents. Our results also indicate that the four biologics seem to differ in the degree to which patients persisted on their treatment regimen. Additionally, relatively higher proportions of bio-experienced patients had dose escalation. Understanding some of these variations across bio-naïve and bio-experienced UC patients may help inform future comparative studies where adjustment for confounders and baseline differences is conducted to assess differences in treatment patterns across the biologics. Such analyses would likely be performed for bio-naïve or bio-experienced patients separately due to the inherent bias introduced from prior biologic treatment exposure and potential non-response or failure that led to initiation of a new biologic therapy.

Limitations of the analyses presented here are those regularly reported for analyses using administrative claims databases. This was an observational, retrospective study, and as such causality cannot be inferred. In addition, because claims databases are designed for reimbursement purposes, reasons for treatment discontinuation, switching, and dose titration cannot be obtained from the claims database. Additionally, this study did not adjust for baseline characteristics or confounders so results should be interpreted with this in mind. Adherence was measured using MPR which may overestimate adherence, as overlapping administrations are not accounted for in the calculation. In addition, insurance medical claims do not indicate the number of days the medication was dispensed for, and the dispensed date on pharmacy claims does not necessarily correspond to the date the medication was administered to or by the patient. Therefore, data imputation (discussed in the Methods section) was conducted to identify the days of supply for each medical and pharmacy claim which may result in over- or under-representation for persistence and dose titration rate for biologics that are intravenous infusions (IFX and VDZ). Patients that hold or miss doses may contribute to changes in mean maintenance dosing in addition to patients that actually have dose titration. This is a limitation of using claims databases for this analysis and, hence, dose titration results should be interpreted with caution. As IFX dosage is weight-based, and information on patient weight was not available in the claims data, dose titration among the IFX cohort was not evaluated. It is important to note that infliximab is the only agent included in the study that is recommended for hospitalized patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous corticosteroids in the AGA guidelines, thus may impact some of the descriptive results presentedCitation26. Furthermore, as these analyses were based only on commercially insured claims databases (i.e. data from patients with private insurance), the results may not be generalizable to patients with Medicare, Medicaid, or those who are uninsured.

Conclusions

This real-world study of UC patients provides further insight into the treatment patterns of the biologics approved for UC during the study period. While these analyses were descriptive in nature, our findings suggest that there is room for improvement in adherence rates across the treatment options studied. Additionally, relatively higher proportions of bio-experienced patients had dose escalation compared to bio-naïve patients. Future studies adjusting for confounders and baseline differences are needed to evaluate the differences in treatment patterns across the biologics.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Janvi Sah and Cynthia Gutierrez were employed at STATinMED Research, which is a paid consultant to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, at the time of study execution. Amanda Teeple and Erik Muser are paid employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. Themistocles Dassopoulos has no conflicts of interest to declare. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

None.

Data availability statement

Due to data user agreement between the authors and the data vendor, data cannot be made publicly available.

References

- Ordás I, Eckmann L, Talamini M, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2012;380(9853):1606–1619.

- Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1756–1770.

- Kornbluth A, Sachar DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American college of gastroenterology, practice parameters committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(3):501–523.

- Naganuma M, Sakuraba A, Hibi T. Ulcerative colitis: prevention of relapse. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;7(4):341–351.

- Armuzzi A, Liguori G. Quality of life in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis and the impact of treatment: a narrative review. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53(7):803–808.

- Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. ACG clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):384–413.

- Lucas AT, Price LSL, Schorzman AN, et al. Factors affecting the pharmacology of antibody–drug conjugates. Antibodies. 2018;7(1):10.

- Chao Y-S, Visintini S. Biologics dose escalation for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a review of clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and guidelines. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2018.

- Patel H, Lissoos T, Rubin DT. Indicators of suboptimal biologic therapy over time in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in the United States. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175099.

- Naegeli A, Hunter T, Grabner M, et al. Identifying inadequate response among ulcerative colitis patients on an advanced therapy in a real-world administrative claims database. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(Supplement_1):S20–S21.

- Armuzzi A, DiBonaventura MD, Tarallo M, et al. Treatment patterns among patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis in the United States and Europe. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0227914.

- Helwig U, Mross M, Schubert S, et al. Real-world clinical effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab and anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha treatment in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease patients: a German retrospective chart review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20(1):211.

- Mantzaris G, Bressler B, Kopylov U, et al. DOP55 a real-world comparison of the effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab and anti-TNF therapies in early treatment initiation with first-line biologic therapy in ulcerative colitis: results from EVOLVE. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(Supplement_1):S092–S094.

- Null KD, Xu Y, Pasquale MK, et al. Ulcerative colitis treatment patterns and cost of care. Value Health. 2017;20(6):752–761.

- Comerford E, DiBonaventura M, Smith T, et al. P024 treatment patterns of biologic therapies used to treat ulcerative colitis: a retrospective database analysis in the United States. Am JGastroenterol. 2019;114:S7.

- Smith TW, DiBonaventura M, Gruben D, et al. Dose escalation and treatment patterns of advanced therapies used to treat ulcerative colitis: a retrospective database analysis in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(Supplement):S353.

- Shah NB, Haydek J, Slaughter J, et al. Risk factors for medication nonadherence to self-injectable biologic therapy in adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(2):314–320.

- Moran K, Null K, Huang Z, et al. Retrospective claims analysis indirectly comparing medication adherence and persistence between intravenous biologics and oral small-molecule therapies in inflammatory bowel diseases. Adv Ther. 2019;36(9):2260–2272.

- Agrawal M, Spencer EA, Colombel JF, et al. Approach to the management of recently diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease patients: a user’s guide for adult and pediatric gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(1):47–65.

- Chan W, Chen A, Tiao D, et al. Medication adherence in inflammatory bowel disease. Intest Res. 2017;15(4):434–445.

- Bewtra M, Fairchild AO, Gilroy E, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease patients’ willingness to accept medication risk to avoid future disease relapse. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(12):1675–1681.

- Bewtra M, Reed SD, Johnson FR, et al. Variation among patients With Crohn’s disease in benefit vs risk preferences and remission time equivalents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(2):406–414.e7.

- Gutiérrez A, Rodríguez-Lago I. How to optimize treatment with ustekinumab in inflammatory bowel disease: lessons learned from clinical trials and real-world data. Front Med. 2021;8:640813.

- D'Amico F, Parigi TL, Fiorino G, et al. Tofacitinib in the treatment of ulcerative colitis: efficacy and safety from clinical trials to real-world experience. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819848631.

- Weisshof R, Aharoni Golan M, Sossenheimer PH, et al. Real-world experience with tofacitinib in IBD at a tertiary center. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(7):1945–1951.

- Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee, et al. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1450–1461.