Abstract

Objective

The objective was to investigate the severity of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency (AADCd) as reported in the published literature and to collate evidence of the clinical manifestations of AADCd, and the impact of the disease on patients, caregivers, and healthcare systems.

Methods

Published articles reporting severity of disease or disease impact were eligible for inclusion in this review. Articles were searched in MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane CENTRAL, TRIP medical, and CRD databases in October 2021. The quality of the included studies was investigated using a modified version of the grading system of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM). Descriptive data of the literature was extracted and a narrative synthesis of the results across studies was conducted. This review is reported according to the PRISMA reporting guidelines for systematic reviews.

Results

The search identified 970 unique reports, of which 59 met eligibility criteria to be included in the review. Of these, 48 included reports provided details on the clinical manifestations of AADCd. Two reports explored the disease impact on patients, while four described the impact on caregivers. Five reports assessed the impact on healthcare systems. Individuals with AADCd experience very severe clinical manifestations regardless of motor milestones achieved, and present with a spectrum of other complications. Individuals with AADCd present with very limited function, which, in combination with additional complications, substantially impact the quality-of-life of individuals and their caregivers. The five studies which explore the impact on the healthcare system reported that adequate care of individuals with AADCd requires a vast array of medical services and supportive therapies.

Conclusions

Irrespective of the ambulatory status of individuals, AADCd is a debilitating disease that significantly impacts quality-of-life for individuals and caregivers. It impacts the healthcare system due to the need for complex coordinated activities of a multidisciplinary specialist team.

Introduction

Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency (AADCd) is an extremely rare and severe autosomal recessive disorder. Prevalence is uncertain and current predictions suggest birth rates of 1:90,000 in the US, 1:118,000 in Europe, and 1:182,000 in JapanCitation1. The prevalence in the US population at risk is approximately 0.112% or 1:900, and the estimated new-born incidence in an at-risk population is approximately 1:41,000 to 1:68,000 birthsCitation2. AADCd is caused by mutations in the dopa decarboxylase (DDC) gene that encodes the enzyme aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC). AADC is a critical enzyme for the synthesis of the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin, which are essential mediators in the synthesis of melatonin, epinephrine, and norepinephrineCitation3. An insufficient or complete lack of synthesis of these neurotransmitters leads to a phenotypic spectrum. In the majority of cases, signs and symptoms present during the first months of life resulting in severe motor and cognitive impairments that do not improve over timeCitation4. AADCd is a life-threatening condition for individuals without direct and dedicated caregiver support. For individuals with access to dedicated caregiver support, the management of AADCd requires consistent and lifelong careCitation5. In routine clinical management, only symptomatic treatment is available, and response to treatment varies substantially among patientsCitation5. Novel gene therapies, using viral vectors containing the human DDC gene to substitute the defected gene, are emergingCitation6,Citation7.

In 2017, Wassenberg et al.Citation5 published an evidence-based clinical guideline for diagnosing and treating AADCd based on a literature search conducted in December 2015. Over the past 7 years, there have been several advancements in investigational gene therapies, and several case reports of individuals with AADCd have been published. Therefore, it is the objective of this systematic literature review to produce an up-to-date review of evidence and to classify the clinical manifestations of AADCd by disease severity as the data allow. In addition, this systematic literature review aims to gain a clearer understanding of the impact of the disease on quality-of-life for individuals, their caregivers, and the utilization of resources within healthcare systems.

Methods

This systematic literature review follows best practice in conducting and reporting standards and was conducted in accordance with relevant chapters in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of InterventionsCitation8, the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s guidance for undertaking systematic reviews in healthcareCitation9, and is reported according to the PRISMA 2020 guidelinesCitation10. The PRISMA checklist is reported in Supplementary Table S8.

The search strategy was conducted in the following bibliographic databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane CENTRAL. In addition, due to the rarity of the disease, the Turning Research Into Practice (TRIP) medical database was searched. TRIP searches guidelines, ongoing clinical trials, and systematic reviews. The Centre for Review and Dissemination (CRD) database was also searched specifically for economic and quality-of-life studies. Further to this, an extensive search of grey literature sources was conducted, including: the International HTA database, Open Grey, Open Access Theses and Dissertations, and E-thesis online service (EThOS). Citation analysis, or spider-searching, of included studies was conducted with the literature mapping tool Connected PapersCitation11. The databases were searched on 13 October 2021, and a hand search of grey literature and citation analysis was conducted on 14 January 2022. Search strategies are provided in Supplementary Tables S1–S6. Studies identified across sources were collated and de-duplicated in EndNote.

Two independent reviewers (MD and BĐ) were assigned to screen references for eligibility by title/abstract and full text; any conflicts were resolved by consensus (VV). presents the eligibility criteria for study inclusion. The publication date was limited to December 2015 and onwards to capture peer-reviewed journal articles that have been published since Wassenberg et al.Citation5. When full text screening was complete, validation of all excluded studies was conducted (VV, KB, and RZ). Screening was conducted using Rayyan (https://rayyan.qcri.org). Following screening, the additional step of identifying papers was completed iteratively. This process is sometimes referred to as citation searching or “snowballing” and has been shown to be more sensitive to specific outcome measures than to standard keyword searches. The initial search results were used to retrieve relevant papers, which were, in turn, used in the following ways to identify missed papers:

Table 1. Eligibility criteria for study inclusion and exclusion in the systematic literature review.

The bibliographies of the relevant papers were checked for articles missed by the first search.

The evidence-mapping software tool www.connectedpapers.com was used to screen the Semantic Scholar database for research connected to the already identified papers. This was an additional check for potentially missed papers that were not present in the included papers’ reference list.

A standardized form for data extraction was developed and used to extract and tabulate results. Two reviewers (KB and RZ) performed data extraction on a pre-specified data extraction form: study design, country, sample size, year of publication, intervention, ambulatory status, clinical manifestations, quality-of-life outcomes, and healthcare resource utilization. To better characterize the severity of the disease, a matrix was created to categorize the clinical manifestations reported on non-ambulatory, ambulatory, and mixed (both ambulatory and non-ambulatory) patient populations. For this systematic literature review, we defined ambulatory patients as individuals who can walk (without or with limited assistance and do not require full support). All other individuals were classified as non-ambulatory. All included studies were assessed for quality using a modified version of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) grading systemCitation12. Systematic reviews of n-of-1 trials and observational studies with dramatic effects were considered “high” level of evidence; non-randomized controlled cohort/follow-up studies were considered "moderate” level of evidence; and case-series, case-control studies or historically controlled studies, and mechanism-based reasoning were considered “low” level of evidence.

Results

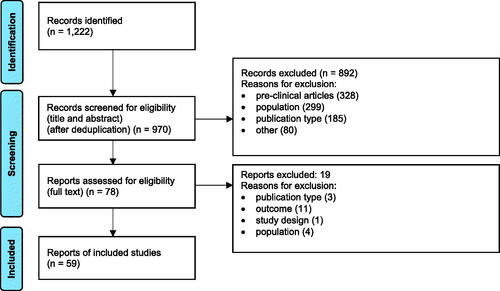

The searches identified 970 unique records, of which 59 reports were included: 48 reported signs and/or symptoms of individuals with AADCd, two reported on the impact of disease on patients, four described the impact of disease on caregivers, and five reported the disease impact on healthcare systems. The PRISMA Flow Diagram is reported in . Reasons for exclusion after full text review are reported in Supplementary Table S9.

Clinical manifestations

Clinical signs and symptoms of all patients, irrespective of ambulatory state, were described in 32 studies and reported in 48 independent reports (24 journal articles and 24 conference abstracts). As shown in , most of the studies were case reports/series or before–after study designs. More precisely, the review identified 25 case series and case reports (52%), 15 before and after studies (31%), three prospective cohort studies (6%), three cross-sectional studies (6%), and two retrospective cohort studies (4%). The number of patients was low, ranging from single cases to studies reporting clinical manifestations of 64 patients. The majority of studies (75%) did not explicitly report patients’ country of residence. Of the studies that reported study country location, the most frequent countries were Taiwan (five studies), China and Italy (two studies), and Brazil, France, and multinational (one study each, respectively).

Table 2. Characteristics of identified studies concerning AADCd clinical manifestations.

Clinical manifestations of AADCd were heterogenous across the identified studies and formed nine categories, as followsCitation5,Citation32,Citation58: (i) motor function, (ii) autonomic dysfunction, (iii) central nervous system (CNS) and mental status disorders, (iv) behavioural problems, (v) sleep disorders, (vi) respiratory problems, (vii) endocrine problems, (viii) ophthalmological problems, and (ix) gastrointestinal problems. presents the categorization of the signs and symptoms and the number of patients that reported with signs and symptoms. Most individuals were non-ambulatory with a broad spectrum of other disease-related disorders. For studies reporting ambulatory status, ambulatory patients had fewer reported disease manifestations compared to studies reporting disease severity in non-ambulatory and mixed populations ( details all included studies presented in Supplementary Table S7). The three most frequent clinical manifestations identified were dystonia, hypotonia, and oculogyric crises.

Table 3. Clinical manifestations per category.

Table 4. Clinical manifestations per ambulatory ability.

Health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL)

Studies reporting HRQoL in AADCd can be divided into two broad categories: studies reporting the (i) quality-of-life of individuals and (ii) quality-of-life of caregivers. None of the identified studies reporting on HRQoL divided results by disease severity category (i.e. ambulatory, non-ambulatory), although studies emphasized the need for such research in the future. One study (results reported as a conference abstractCitation59 and peer-reviewed journal articleCitation60) was conducted with the primary objective to measure the quality-of-life of 13 individuals with AADCd. The impact of quality-of-life on caregivers was also investigated in one study and reported in four publications (). Studies were conducted in Europe (Italy, Spain, and Portugal) and the US by telephone interviews with caregivers.

Table 5. Identified studies reporting health-related quality-of-life of patients and caregivers.

The study by Skrobanski et al.Citation61 reported a mixed population and aimed to show the spectrum of different clinical manifestations (motor function, cognition/communication, gastrointestinal symptoms, and movement disorders) affect on individuals’ quality-of-life in terms of daily activities, social interactions, emotions, and behaviour. The study reported that all individuals with AADCd are entirely dependent on their caregivers in every aspect of their day-to-day lives. This dependency leads to the inability to socialize with peers which was reported, in particular, to severely affect individuals’ emotional wellbeing.

The study reporting impact on caregivers of individuals with AADCd categorized HRQoL impact as proximal, distal, and familyCitation61. Proximal impact includes limited time for other activities, the need for very detailed planning and scheduling, emotional and physical exhaustion, and sleep disturbance. Distal impact was described as difficulties connected to finance (health-related spending and reduced income), work (changing job or need for flexible work time), social/leisure activities (reduction or absence), and relationship quality with the partner and family. Proximal and distal impacts combined have a subsequent impact on the familyCitation61,Citation62. A separate analysis and report of this study focused more on the distal impact of caregiver HRQoL. The authors reported that direct and indirect activities related to caring for a child with AADCd totalled, on average, 109 h per week, with additional unpaid support from the partner of 37 h per weekCitation64. In addition to loss of work income, individuals required support of paid nurses for an average of 27 h per week. Supplemental nursing support is not always paid from a national service and is often an out-of-pocket expense for families. According to the study results, 43% of the primary caregivers reported that they stopped working outside of the home and 29% reported having reduced their paid working hours. An additional 14% of caregivers reported that their partners also reduced their working hoursCitation64.

In one of the analyses, the EQ-5D instrument was tested for adequacy in capturing the quality-of-life of caregivers of individuals with AADCdCitation63. The report concluded that EQ-5D may not sufficiently capture the HRQoL of caregivers, especially with regards to usual activities, as caregivers’ perceptions of these are so far removed from that of the general population.

Impact on the healthcare system

We have identified three studies published in five reports that described resource utilization in individuals with AADCd living in the USCitation65, the UKCitation66, and Europe (Spain, Italy, and France)Citation67. The European study reported subgroup analyses in FranceCitation68 and ItalyCitation69, respectively. The total number of reported patients was 32. All three studies generate evidence concerning resource utilization from clinician interviews and from electronic health records of individuals with AADCd ().

Table 6. Characteristics of identified studies concerning AADCd healthcare resource utilization and impact on the healthcare system.

According to these studies (), there is no difference between ambulatory and non-ambulatory patients regarding utilization of biochemical tests and initial medical procedures. However, in other categories, such as use of the medical devices, frequency of healthcare professionals’ visits, hospitalizations, and paramedical support, there is an evident trend of much higher resource consumption among non-ambulatory patients. The majority of non-ambulatory patients require hospitalization, with repeated hospitalization occurring up to twice a year in ItalyCitation69, and three times per year in FranceCitation68. On average, individuals with AADCd use six medications.

Table 7. Annual healthcare resource utilization per category per ambulatory/non-ambulatory patient.

Quality assessment of included studies

Fifty-nine included studies were assessed for their quality with a modified version of the grading system of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM). Thirty-eight studies were considered “low” level of evidence (case-series, case-control studies, or historically controlled studies, and mechanism-based reasoning studies). In contrast, 21 studies were considered “moderate” level of evidence (non-randomized controlled cohort/follow-up study). Randomized trials or n-of-1 trials and observational studies with a dramatic effect or “high” level of evidence studies were not identified.

Discussion

AADCd is a rare and severe genetic disorder that is well documented to cause a broad spectrum of clinical signs and symptoms that seriously impact the daily lives of affected individuals and requires multidisciplinary careCitation5,Citation59,Citation61. This comprehensive systematic literature review has identified evidence related to diagnosis and management of individuals with AADCd published since December 2015. The updated findings are consistent with previous results demonstrating that individuals with AADCd are severely impacted by their disease.

The main strength of this study is that it is an updated and comprehensive review of the evidence base, which has allowed, in part, for the stratification of patients by severity (ambulatory status). These findings demonstrate that the disease is severe regardless of ambulatory status. Furthermore, this study reported on the broad spectrum of clinical manifestations of AADCd beyond gross motor impairment. Additionally, this systematic review also captured the disease burden on a wider scale to include quality-of-life aspects of both patients and their caregivers. Healthcare resource utilization burden was also identified to comprehensively demonstrate the considerable impact of the disease. Finally, this is a systematic review, which differs from a scoping review. Per Munn et al.Citation70, scoping reviews have the purpose to identify knowledge gaps within a field of literature, clarify concepts and investigate research methodology, while our systematic literature review provides an extensive and up-to-date analysis of evidence concerning clinical manifestations of the disease, as well as the impact of the disease on patients, caregivers, and the healthcare system. This systematic literature review explored two other research questions not previously reviewed: (1) the impact of AADCd on HRQoL among both affected individuals and their caregivers, and (2) healthcare resource utilization. This review found that the impact of AADCd on individualsCitation60, their caregivers, and families’Citation61 HRQoL is substantial. While these studies are considered of lower quality, it is consistently reported that the HRQoL of affected individuals is seriously reduced regardless of disease phenotype. In addition, individuals with AADCd are entirely dependent on their caregiver for all essential activities, including feeding. As a result, caring for an individual with AADCd significantly modifies typical daily activities for caregivers and families, resulting in the inability of caregivers to socialize and work outside of the home, impacting their quality-of-lifeCitation61.

All included studies reporting healthcare resource utilization were published in the last 2 years. This emerging evidence provides insight on the necessary reliance of individuals with AADCd on the healthcare system. The findings suggest that healthcare resource utilization for all individuals with AADCd is high and is higher when treating non-ambulatory patients.

There are several limitations with this systematic literature review. This systematic review was restricted to English publications only to allow evaluation of the included studies in detail. This could have led to some patients being missed in the review. Primary research studies of rare diseases, present methodological challenges including small sample sizesCitation71 and weaker study designs which are classified as low level evidence in standard evidence-based medicine hierarchy, specifically, case reports, case series, and before–after studies. Due to these reasons, the internal validity and precision of included studies is impacted. As the analysis in this review does not attempt analytical inference but rather reports a descriptive summary of the humanistic and economic burden of AADCd, the conclusions of this review are not substantially affected by these limitations. All reports detailing clinical manifestations of disease, quality-of-life, and resource utilization add value in understanding AADCd as a rare disease. Additionally, the systematic review does not have a prospective registration (i.e. PROSPERO).

Similarly, given the small number of individuals included in primary studies, there is a risk of some patients being described/studied in multiple studies. Repeat reporting on individuals across reports cannot be entirely resolved without access to patient-level data. Furthermore, most of the studies did not report year of data collection, which also adds to this challenge. Bergkvist et al.Citation72 published a systematic review about the natural history of AADCd and attempted to delineate individual patients by using information from different published studies to re-create patient-level data and develop the database. This synthesis did not utilize this approach; however, the review team did work to minimize the impact of this risk by identifying co-publications and noting characteristics across studies that clearly identify an overlap in individuals or caregivers.

This systematic literature review attempted to group patients by ambulatory and non-ambulatory status. As there are currently no consistent definitions across primary study reports reviewed, judgement was needed for classification based on the details reported in the primary studies. As such, this may have introduced some level of imprecision, however, we do not consider this to change the overall conclusions of this review.

The findings of this review have implications for clinical practice, public health policy, and future research on the management of AADCd. Although health professionals treating individuals with AADCd are well aware of the severity and outcomes of the disease, results of this systematic literature review provide additional insight into the quality-of-life of individuals, their caregivers, and their challenges. In addition, this review provides new insight into the differences in disease severity and healthcare utilization between ambulatory and non-ambulatory patients and demonstrates, irrespective of the phenotype, that AADCd is a severe condition.

As highlighted by this analysis, all patients, regardless of severity, require significant care and resource consumption, and their disease causes a substantial HRQoL and economic burden to their caregivers. All affected individuals, before the introduction of investigational genetic therapy, were only receiving supportive care and symptomatic treatment. Future therapies with the potential to lessen severity could considerably impact affected individuals’ HRQoL and that of their caregivers. The summary of the HRQoL and resource utilization studies should further inform the broader organization of care of individuals with AADCd and provide insight in unmet support needs for caregivers.

The rarity of this condition requires detailed and clear instructions of how individuals and caregivers should be supported in their communities. Due to the limited number of healthcare professionals with experience with this rare disease, managing individuals with AADCd requires centralized diagnostic and therapy prescription in the high-volume centres which support similar conditions. Education for health professionals with less experience in diagnosis and treatment of AADCd should be provided. Further research is needed in the HRQoL of individuals and caregivers. A need exists for HRQoL stratification between ambulatory and non-ambulatory patients. Stratification would allow for a better understanding in the benefits that potential treatments can be more precisely quantified, such as a treatment that can modify a patient’s motoric disorder from a non-ambulatory to an ambulatory condition. To support consistency of data collection, a validated HRQoL questionnaire needs to be validated and mapped into the appropriate generic HRQoL instrument from which utilities can be generated for health economic models.

Conclusion

In conclusion, irrespective of the ambulatory status, AADCd has severe clinical manifestations and leads to significant quality-of-life reduction and impacts the healthcare system due to the need for complex and coordinated activities of a multidisciplinary specialist team. However, it is evident that a non-ambulatory health state leads to more severe clinical manifestations, a more significant impact on the quality-of-life for both patients and their caregivers, and a higher utilization of healthcare resources.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored and funded by PTC Therapeutics.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

KB, RZ, KS, and AR are employees of PTC Therapeutics. VV, LT, MD, and BD received funding from PTC Therapeutics through Core Models Limited to conduct the research and develop the manuscript. PTC Therapeutics had no influence on the study conduct, analyses, or interpretation of results, and authors carried out the study according to appropriate systematic literature review guidelines. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

AADCdseverity_supplemental_file_CLEAN.docx

Download MS Word (170.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Greg Fuest, former PTC Therapeutics employee, for his invaluable contributions to this project and manuscript.

References

- Whitehead N, Croxford J, Erickson S, et al. Estimated prevalence of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency in the United States, European Union, and Japan. Annual Congress of the European Society for Gene and Cell Therapy; 2018; Lausanne: Biology; 2018.

- Hyland K, Reott M. Prevalence of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency in at-risk populations. Pediatr Neurol. 2020;106:38–42.

- Palma J-A, Norcliffe-Kaufmann L, Fuente-Mora C, et al. 154. Disorders of the autonomic nervous system: autonomic dysfunction in pediatric practice. In: Swaiman KF, Ashwal S, Ferriero DM, Schor NF, Finkel RS, Gropman AL, editors. Swaiman's pediatric neurology. 6th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2017. p. 1173–1183.

- Himmelreich N, Montioli R, Bertoldi M, et al. Aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: molecular and metabolic basis and therapeutic outlook. Mol Genet Metab. 2019;127(1):12–22.

- Wassenberg T, Molero-Luis M, Jeltsch K, et al. Consensus guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):12.

- Pearson TS, Gupta N, San Sebastian W, et al. Gene therapy for aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency by MR-guided direct delivery of AAV2-AADC to midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):4251.

- Tai C-H, Lee N-C, Chien Y-H, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of eladocagene exuparvovec in patients with AADC deficiency. Mol Ther. 2022;30(2):509–518.

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, et al., editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.3. (updated February 2021). London: Cochrane; 2022.

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic reviews: CRDs guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. 2009. Available from: https://www.york.ac.uk/crd/guidance/.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

- Connected Papers. 2022. [cited 2022 Jan 25]. Available from: https://www.connectedpapers.com/.

- OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. The Oxford levels of evidence 2. 2021. [cited 2021 Oct 08]. Available from: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence.

- Bankiewicz K, Pearson T, Grijalvo-Perez A, et al. Restoring AADC enzyme synthesis in AADC deficiency: MRI-guided delivery of AAV2-hAADC gene therapy to the midbrain. Movement Dis. 2019;34:S229.

- Chien Y-H, Lee N-C, Tseng S-H, et al. AGIL-AADC gene therapy results in sustained improvements in motor and developmental milestones over 5 years in children with AADC deficiency. Neurology. 2019;92(15):P4.6-058.

- Chien Y-H, Lee N-C, Tseng S-H, et al. Efficacy and safety of AAV2 gene therapy in children with aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: an open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2017;1(4):265–273.

- Tseng CH, Chien YH, Lee NC, et al. Gene therapy improves brain white matter in aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Ann Neurol. 2019;85(5):644–652.

- Chien Y-H, Hwu PW-L, Lee N-C, et al. Improved motor function in children with AADC deficiency treated with eladocagene exuparvovec (PTC-AADC): interim findings from a phase 2 trial. Mol Ther. 2020;28(4):560.

- Chien Y-H, Hwu PW-L, Lee N-C, et al. Improved motor function in children with aromatic L-Amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency treated with eladocagene exuparvovec (PTC-AADC): interim findings from a phase 2 trial. 2021. Neurology. 2021;96(15 Supplement):2366.

- Cordeiro D, Garrett B, Cohn R, et al. Outcome of patients with inherited neurotransmitter disorders. Can J Neurol Sci. 2018;45(5):571–576.

- Gowda VK, Vegda H, Nagarajan BB, et al. Clinical profile and outcome of Indian children with aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: a primary CSF neurotransmitter disorder mimicking as dyskinetic cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Genet. 2021;10(2):85–91.

- Gupta N, Pearson T, Imamura-Ching J, et al. Gene therapy for the treatment of primary l-aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency in children. J Neurosurg. 2020;132(4):99.

- Hasegawa Y, Nishi E, Mishima Y, et al. Novel variants in aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: case report of sisters with mild phenotype. Brain Dev. 2021;43(10):1023–1028.

- Kuseyri Hübschmann O, Mohr A, Friedman J, et al. Brain MR patterns in inherited disorders of monoamine neurotransmitters: an analysis of 70 patients. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2021;44(4):1070–1082.

- Hwu PW-L, Chien Y-H, Lee N-C, et al. Safety and improved efficacy outcomes in children with aadc deficiency treated with AGIL-AADC gene therapy: results from three clinical trials. Ann Neurol. 2019;86:S148–S49.

- Hwu PW-L, Pachelli PE, Chien YH, et al. Safety and improved efficacy outcomes in children with AADC deficiency treated with eladocagene exuparvovec gene therapy: results from three clinical trials. Cytotherapy. 2021;23(4):33.

- Hwu PW-L, Chien Y-H, Lee N-C, et al. Improved motor function in children with AADC deficiency treated with eladocagene exuparvovec (PTC-AADC): interim findings from a phase 1/2 study. Mol Ther. 2020;28(4):272.

- Hwu PW-L, Chien Y-H, Lee N-C, et al. Improved motor function in children with AADC deficiency treated with eladocagene exuparvovec (PTC-AADC): interim findings from a phase 2 trial. 46th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuropediatrics; 2021; Virtual: Neuropediatrics; 2021.

- Hwu PW-L, Chien Y-H, Lee N-C, et al. Improved motor function in childrenwith aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency treated with eladocagene exuparvovec (PTC-AADC): compassionate use study. Neurology. 2021;96(15):2387.

- Hwu PW-L, Chien Y-H, Lee N-C, et al. Improved motor function in children with AADC deficiency treated with eladocagene exuparvovec (PTC-AADC): compassionate use study. Mol Ther. 2020;28(4):270–271.

- Hwu W-L, Chien Y-H, Lee N-C, et al. Natural history of aromatic l-Amino acid decarboxylase deficiency in Taiwan. In: Morava E, Baumgartner M, Patterson M, Rahman S, Zschocke J, Peters V, editors. JIMD reports. Vol. 40. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2018. p. 1–6.

- Kojima K, Anzai R, Ohba C, et al. A female case of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency responsive to MAO-B inhibition. Brain Dev. 2016;38(10):959–963.

- Saberian S, Rowan P, Hammes F, et al. POSA192 disease burden of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency: signs and symptoms. Value Health. 2022;25(1):S124.

- Le Dissez C, Jocelyn D, Hammes F, et al. PRO2 burden of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency (AADC-D) in France with a FOCUS on patient symptoms and motor milestones development. Value Health. 2021;24:S197.

- Fernández-Cortés F, Saberian S, Patel P, et al. POSC8 burden of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency in Italian patients from symptomatology and motor development perspective. Value Health. 2022;25(1):S33–S34.

- Longo C, Montioli R, Bisello G, et al. Compound heterozygosis in AADC deficiency: a complex phenotype dissected through comparison among heterodimeric and homodimeric AADC proteins. Mol Genet Metab. 2021;134(1–2):147–155.

- Lotha K, Green L, Pope S, et al. Oculogyric crisis… don't forget the neurotransmitters! A rare case of AADC deficiency. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61:83.

- Marchese F, Faedo E, Vari MS, et al. Atypical presentation of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency with developmental epileptic encephalopathy. J Pediatr Epilepsy 2021;10(03):124–127.

- Mastrangelo M, Baglioni V, Cesario S, et al. Neurocognitive and motor outocome in five patients with aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. J Inherited Metab Dis. 2019;42:277.

- Mastrangelo M, Cesario S, Baglioni V, et al. Mild adaptive impairment and treatable diarrhea as novel phenotypic signs of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. J Inherited Metab Dis. 2019;42:277.

- Micallef J, Stockler-Ipsiroglu S, van Karnebeek CD, et al. Recurrent dystonic crisis and rhabdomyolysis treated with dantrolene in two patients with aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Neuropediatrics. 2020;51(3):229–232.

- Monteleone B, Hyl K. Case report: discovery of 2 gene variants for aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency in 2 African American siblings. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):12.

- Montioli R, Battini R, Paiardini A, et al. A novel compound heterozygous genotype associated with aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: clinical aspects and biochemical studies. Mol Genet Metab. 2019;127(2):132–137.

- Kojima K, Nakajima T, Taga N, et al. Gene therapy improves motor and mental function of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Brain. 2019;142(2):322–333.

- Onuki Y, Ono S, Nakajima T, et al. Dopaminergic restoration of prefrontal cortico-putaminal network in gene therapy for aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Brain Commun. 2021;3(3):fcab078.

- Onuki Y, Ono S, Nakajima T, et al. Persistent and efficient transduction of the putamen following gene therapy for aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Mov Dis. 2021;36:S580.

- Pappan KL, Kennedy AD, Magoulas PL, et al. Clinical metabolomics to segregate aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency from drug-induced metabolite elevations. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;75:66–72.

- Pearson T, Gilbert L, Opladen T, et al. AADC deficiency from infancy to adulthood: symptoms and developmental outcome in an international cohort of 63 patients. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2020;43(5):1121–1130.

- Gilbert L, Black K, Opladen T, et al. The natural history of AADC deficiency: a retrospective study. Ann Neurol. 2019;86:S97–S98.

- Pearson T, Gupta N, Grijalvo-Perez A, et al. Gene therapy for AADC deficiency: MRI-guided delivery of AAV2-hAADC to the midbrain. Ann Neurol. 2019;86(S23):S84.

- Portaro S, Gugliandolo A, Scionti D, et al. When dysphoria is not a primary mental state: a case report of the role of the aromatic L-aminoacid decarboxylase. Medicine. 2018;97(22):e10953.

- Segantini TG, Spini GR, Gianchini-Segantini T, et al. Unraveling AADC deficiency: natural history in a Brazilian cohort of patients. J Inherited Metab Dis. 2019;42:382–383.

- Spitz MA, Nguyen MA, Roche S, et al. Chronic diarrhea in L-Amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency: a prominent clinical finding among a series of ten French patients. JIMD Rep. 2017;31:85–93.

- Viviani C, Buelli E, Fierro G, et al. Anesthesia management for cesarean delivery in a woman with aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: a case report. A A Pract. 2020;14(10):e01275.

- Dai W, Lu D, Gu X, et al. Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency in 17 mainland China patients: clinical phenotype, molecular spectrum, and therapy overview. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020;8(3):e1143.

- Wen Y, Wang J, Zhang Q, et al. The genetic and clinical characteristics of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency in mainland China. J Hum Genet. 2020;65(9):759–769.

- Dai L, Ding C, Fang F. A novel DDC gene deletion mutation in two Chinese mainland siblings with aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Brain Dev. 2019;41(2):205–209.

- Yardi N, Yardi R. Cases of AADC deficiency need detection as a treatable cause of dystonia and persistent upward deviation of eyes masquerading as seizures. J Neurol Sci. 2019;405:77.

- Bakidou A, Werner C, Buesch K. PRO8 age at onset and frequency of clinical signs and symptoms in patients with AADC deficiency: a systematic literature review. Value Health. 2020;23:S691.

- Williams K, Skrobanski H, Werner C, et al. Symptoms and impact of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency: a qualitative study and the development of a patient-centred conceptual model. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(8):1353–1361.

- Williams K, Skrobanski H, Werner C, et al. PRO53 symptoms and impact of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency (AADCd): a qualitative study. Value Health. 2021;24:S206–S207.

- Skrobanski H, Williams K, Werner C, et al. The impact of caring for an individual with aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency: a qualitative study and the development of a conceptual model. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(10):1821–1828.

- Skrobanski H, Williams K, Werner C, et al. PRO52 a qualitative study on the impact of caring for an individual with aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency (AADCd). Value Health. 2021;24:S206.

- Williams K, Skrobanski H, Buesch K, et al. PRO46 measuring carer utility in rare paediatric disease: a mixed methods case study in aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency (AADCd). Value Health. 2021;24:S205.

- Buesch K, Williams K, Skrobanski H, et al. PRO51 caring for an individual with aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency: analysis of reported time for practical and emotional care and paid/unpaid help. Value Health. 2021;24:S206.

- DiBacco ML, Hinahara J, Goss TF, et al. Burden of illness in aromatic L amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency. ISPOR 2021; Virtual; 2021.

- Boehnke A, Balman L, Davidson I, et al. Aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency in UK – burden of disease. ISPOR 2022. Washington (DC): USA Area and Virtual; 2022.

- Saberian RP, Patel P, Fernandez-Cortes F, et al. Disease burden of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency: healthcare resource use (HCRU) overall and by motor milestone achievement. Virtual ISPOR Europe 2021; Virtual; 2021.

- Le Dissez C, Jocelyn D, Hammes F, et al. PRO28 healthcare resource use (HCRU) of patients with aromatic L-Amino acid decarboxylase deficiency (AADC-D) in France. Value Health. 2021;24:S202.

- Fernández-Cortés F, Saberian S, Patel P, et al. POSC69 healthcare resource consumption associated with aromatic L-Amino acid decarboxylase deficiency (AADC-D) in Italy. Value in Health. 2022;25(1):S99–S100.

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

- Mitani AA, Haneuse S. Small data challenges of studying rare diseases. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e201965–e65.

- Bergkvist M, Stephens C, Schilling T, et al. Aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency – a systematic review. ICIEM 2021, Sydney, Australia; 2021.