Abstract

Objective

To evaluate efficacy and tolerability of the nonbenzodiazepine antispasmodic pridinol (PRI), as an add-on treatment in patients with muscle-related pain (MRP).

Methods

Exploratory retrospective analysis of depersonalized routine data provided by the German Pain e-Registry (GPeR) focusing on pain intensity, pain-related disabilities in daily life, wellbeing, and drug-related adverse events (DRAEs).

Primary endpoint based on a global response composite of (a) a clinically relevant analgesic response (relative improvement ≥50% and/or absolute improvement ≥ the minimal clinical important difference) for pain intensity and disability in combination with (b) an improvement in wellbeing (all at end of treatment vs. baseline), and (c) lack of any DRAEs.

Results

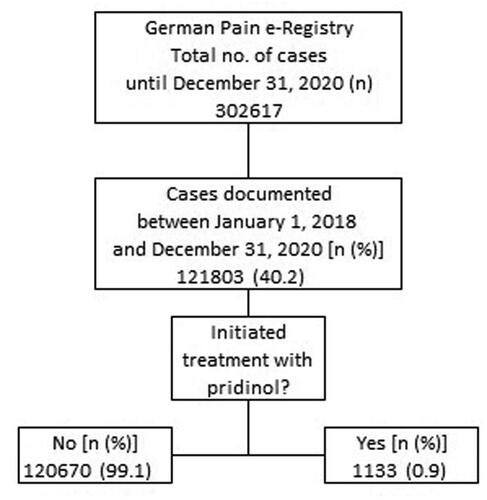

Between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2020, the GPeR collected information on 121,803 pain patients of whom 1133 (0.9%; 54.5% female, mean ± SD age: 53.9 ± 11.8 years) received add-on PRI for the treatment of (mostly acute) MRP originating predominantly in the (lower) back (43.2%), lower limb (26.4%), or should/neck (21.1%). Average daily dose was 7.8 ± 1.8 (median 9, range 1.5–13.5) mg, duration of treatment 12.0 ± 10.2 (median 7, range 3–63) days. In total, 666 patients (58.8%) reported a complete, 395 (34.9%) a partial, and 72 (6.4%) patients no response – either because of lack of efficacy (n = 2, 0.2%) or DRAEs (n = 70, 6.2%). In response to PRI, 41.7% of patients documented a reduction of at least one other pain medication and 30.8% even the complete cessation of any other pharmacological pain treatments.

Conclusion

Based on this real-world data of the German Pain e-Registry, add-on treatment with PRI in patients with acute MRP under real-world conditions in daily life was well tolerated and associated with an improvement of pain intensity, pain-related disabilities, and overall wellbeing.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Muscle pain is one of the most common pain problems worldwide.

In the majority of cases, muscle pain is temporary, transient, and benign in nature. However, people affected may still experience severe pain and significant pain-related disabilities in daily life activities that may require temporary drug treatment – also to be able to undertake the non-drug treatment measures necessary to prevent recurrence.

Current treatment recommendations for muscle pain are largely “non-specific” and limited to symptomatic pain-relieving measures (e.g. NSAIDs), whereas muscle relaxants are currently not recommended (primarily due to insufficient efficacy data from controlled clinical trials) but are nevertheless frequently prescribed.

In our analysis of depersonalized data from the German Pain e-Registry, the add-on treatment with pridinol proved to be effective and well tolerated in patients with muscle pain who have so far responded only insufficiently to recommended analgesic and adjuvant therapies

The available real-world evidence data on efficacy and tolerability of PRI show a beneficial and clinically relevant activity, but confirmation by active or placebo-controlled clinical studies is still lacking.

Background

Acute muscular pain of the postural and locomotor system in general as well as acute myofascial pain in the narrower sense are among the most frequent reasons for pain-related presentations in medical practice and are responsible for the majority of pain causes in patients with so-called non-specific (low) back painCitation1,Citation2. Due to a recent representative cross-sectional analysis of the Robert-Koch Institute, the one-year prevalence of non-specific (low) back pain in Germany is 61.3% of the total population (females: 66.0% vs. males: 56.4%)Citation3, and in approximately 85% of these patients back pain is classified as non-specificCitation4.

Despite the mostly self-limiting and generally benign nature of acute muscle-related painCitation5–8, the individual physical burden for those affected is frequently high and the pain-related impairments in daily life considerable, which is why many patients seek specific medical helpCitation5,Citation6. The aim of such consultations is – after the exclusion of serious specific causes (so-called red flags) with the need for immediate countermeasures – to inform affected persons about the benign and the self-limiting course of their complaints as well as the rapid reduction of the individual burden through suitable non-pharmacological procedures and complementary pharmacological therapiesCitation6,Citation7.

Although the international scientific recommendations for activating non-pharmacological methods are largely consistent with those that are implemented in daily practice, there is a considerable discrepancy between guideline recommendations and practical implementation of pharmacological therapiesCitation5,Citation8–10. This is reflected internationally in different prescribing patterns across countries and nationally in discrepancies between various health care sectorsCitation8,Citation11–19.

Across all guidelines, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are considered the drugs of first choice for the symptomatic treatment of acute muscular pain, whereas muscle tone-reducing agents – mostly justified by insufficient evidence and the risk of possible side effects (usually with reference to the side effect spectrum and the abuse potential of benzodiazepines) – are not recommended there or at best only of tertiary importanceCitation6,Citation7. However, from a pathophysiological point of view, the use of so-called antispasmodics – at least of those out of the group of non-benzodiazepine muscle relaxants – seems to make more sense for a cause-oriented treatment of patients with muscular pain versus the predominantly symptomatic mode of action of NSAIDs.

In Europe, the spectrum of available antispasmodics has been significantly narrowed in recent years due to several risk-benefit assessments published by the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and consecutive extensions of the official product characteristic and the inclusion of new side effects (tizanidine)Citation20, restrictions on approval (tolperisone)Citation21, the temporary suspension (tetrazepam)Citation22, or even withdrawal (flupirtine) of marketing authorizationCitation23. Nevertheless, certain antispasmodics – such as pridinolCitation24, which was reapproved in Germany in 2018 and has been subsequently approved in other countries of the European Union as well – are proving very popular in daily practice, with increasing prescription numbersCitation25.

In light of this – and due to the facts that (a) the national German reference guideline for non-specific low back pain gives a negative recommendation for all muscle relaxants in general and (b) the published scientific evidence for pridinol is neglectable – the German Pain Association initiated the non-interventional research project PriMePain to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of pridinol (PRI) in patients with musculoskeletal/muscle-related pain (MRP) under real-life conditions of the German health care system.

Methods

Study design

PriMePain was a retrospective, non-interventional, single-cohort study of patients with MRP who received a treatment with PRI as part of routine care. For this purpose, real-world data originally prospectively documented for routine purposes via the German Pain e-Registry (GPeR) – a national web-based pain treatment registry developed in collaboration with the German Pain Association—were analyzed.

To relativize the disadvantages of the noninterventional study approach and the methodological limitations associated with the use of real-life data from routine care, this evaluation followed a predefined statistical analysis concept and a specific endpoint analysis with respect to considerations relevant to everyday life – focusing on efficacy (pain intensity and pain-related disabilities), tolerability (overall wellbeing), and safety (drug-related adverse events).

Study objective

The objective of this study was the evaluation of safety, tolerability, and efficacy of PRI in patients with MRP under conditions of daily life.

Study medication

PRI, a nonbenzodiazepine muscle relaxant acting via cholinergic antagonism of muscarinergic acetylcholine receptorsCitation24,Citation25 has been reauthorized in Germany for the treatment of central and peripheral muscle spasms, torticollis, lumbago, and general muscle pain in adult patients end of 2017 and first time approved in 2020 in further European countries such as the United Kingdom, Poland, and Spain. At present, pridinol is one of only two muscle relaxants approved for the treatment of peripheral muscle spasms associated with (low) back pain in GermanyCitation26.

After oral administration, PRI reaches its maximum plasma concentration within 1 h (regardless of whether it was taken before, with or after meal) and distributes evenly in different body tissuesCitation27. PRI is primarily metabolized via cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C19 and 2B6 to 4-hydroxypridinol, its main metaboliteCitation28, and renally excreted with a median elimination half-life of 18.3 h either unchanged or as glucuronidated/sulfoconjugated drugCitation27–29.

Recommended maintenance dose is ½ to one tablet (1.5–3 mg) TID and one to two tablets at bedtime for the interval prophylaxis of nocturnal cramps. Treatment with PRI evaluated in this study followed medical requirements according to the shared/mutual decisions of physicians and their patients and based exclusively on individual patient needs and the recommendations given in the current Summary of Product CharacteristicsCitation24.

Study population

Due to the retrospective study approach, the evaluation was neither based on a formal case number calculation nor on specific in- and exclusion criteria. The statistical analysis based on data which were recorded between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2020, on any patients with MRP who received a treatment with PRI for the first time and who reported their experiences with this treatment using the standardized self-disclosure instruments of the German Pain Questionnaire and the German Pain Diary.

Information on current pain medication was an essential component of these patient questionnaires and reported dates of first and last dose of PRI were taken for the calculation of the length of the individual treatment evaluation periods, of which all were included in the evaluation (i.e. without a priori specifications regarding the duration of treatment).

Data source

This analysis based exclusively on routine data of the GPeR. All analyses have been carried out retrospectively, exclusively using the data already available at the time of the cut-off date (i.e. 1 January 12021) and after complete depersonalization concerning patient and institution or treating physician.

The GPeR was developed to provide patients and physicians with a standardized electronic documentation program named iDocLiveFootnotei to gather, evaluate and compare patient reported information on demographics, medical history, pretreatment, pain characteristics, and treatment response in daily practice. Data were prospectively self-reported by patients as part of routine use of the electronic documentation tools provided by the online service iDocLive and controlled as well as complemented by related information of the physicians where appropriate and needed. End of December 2021, the GPeR network consisted of 825 pain specialists, 836 physicians and 2710 non-medical pain experts (e.g. psychotherapists and physiotherapists), who cared for approx. 240,000 patients per quarter in 237 pain centres throughout Germany.

Study assessments

Evaluation of effectiveness

The questionnaires used by GPeR were those developed and recommended by national pain associations and patient organizations and capture a wide range of relevant patient and treatment informationCitation30,Citation31. Instruments are recommended and validated by the German Pain Association and the German Pain League for the routine documentation within the framework of the quality assurance agreement Special Pain Therapy according to § 135 para. 2, book V of the German Social Conduct of LawCitation32.

Assessment of the effectiveness of PRI as part of this study based solely on patient perceptions and patient-reported information on pain intensity, pain-related disabilities in daily life activities, and overall wellbeing as reported in the German Pain Questionnaire. Pain intensity was measured using the average 24-h pain intensity index (PIX), calculated as arithmetic mean of the lowest, median, and highest 24-h pain intensities reported by patients on a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS; 0 = “no pain” and 100 = “worst pain conceivable”)Citation33,Citation34. MRP-related disabilities in daily life were assessed using a modified version of the pain disability index (mPDI), which recorded the degree of functional restrictions in daily life activities on a 100 mm VAS (with 0 = “none” and 100 = “worst conceivable”) with respect to seven distinct domains (related to home and family activities, recreation, social activities, occupation, self-care/personal maintenance, sleep, and overall QoLCitation34. The Marburg Questionnaire on Habitual Health Findings (MQHHF) was used to evaluate overall wellbeing (an essential ingredient in the quality-of-life concept of pain patients) with a seven-item scale for predominantly positive skills on which the patients rated their general wellbeing [using a 5-step numerical rating scale (NRS5): 0 = “not true at all” and 5 = “applies very much”] in the last weekCitation34,Citation35.

After baseline evaluation, patients completed standardized pain diaries (containing identical sets of validated instruments as the German Pain Questionnaire) using the online application iDocLive and provided information on their current health status and their response to the medication according to individual patient needs and/or established routines.

Data were entered by patients and practice staff via the electronic documentation tool iDocLive using standardized and authorized terminal devices (desktop computers, notebooks, or tablets) either directly in the pain centers participating in the GPeR (e.g. at baseline – before start of treatment as well as during follow-up) or from home (only during follow-up). To ensure a standardized presentation of the different questionnaire instruments (especially the visual analogue scales) on different screen sizes, automatic adjustments were made by the electronic documentation systemCitation35.

All data and patient information collected using the aforementioned procedures and processes complied with the specifications of the two German Pain Societies and the recommendations of the German Pain League as the responsible patient organization. To guarantee the correctness and completeness of the data, the patients in the participating pain medicine facilities were familiarized with the handling of the input devices by trained staff and informed about the structure of the self-report instruments and their processing.

All information documented by the patients were 100% checked by the treating physicians and approved prior entry into the German Pain e-Registry.

Concomitant medication

Since patients were treated according to their individual needs, no specifications were in place on the use of pridinol or concomitant medications. Physicians were able to prescribe, and patients were free to take any medications and/or non-pharmacological measures necessary to provide adequate supportive care for any condition required, however were asked to report any treatment changes to the registry.

Safety and tolerability measures

Safety analyses were based on patient reports on drug-related adverse event (DRAE), collected via specific questionnaires provided by the GPeR. For this analysis, DRAEs were defined as any patient-reported adverse reaction to PRI and did not necessarily have to be causally related to the treatment under evaluation. Adverse events reported were classified according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA, version 23.0, 2021).

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using the complete set of anonymized data provide by the GPeR for patients who fulfill the above-mentioned criteria and based on a modified intent-to-treat (ITT) approach, i.e. data from all patients who took at least one dose of pridinol and who had at least one post-baseline/post-dose measure were evaluated. Linear interpolation was used to impute intermittent missing scores and the conservative last observation carried forward (LOCF) method to impute missing scores after discontinuation. The corresponding completed data set formed the basis for all analyses.

According to the exploratory non-interventional concept, available data were retrospectively evaluated and appropriate descriptive statistical methods were used. For categorical data, the absolute and relative (where necessary adjusted) frequencies were calculated, and cumulative frequencies for ascending/descending scale levels were analyzed for defined limit ranges. Interval-scaled data were evaluated through their mean value, standard deviation, median, range (minimum – maximum) and 95% confidence intervals. Where sensible and possible, cut-off values were grouped categorically and provided with corresponding frequency analyses. The use of biometric test procedures (Wilcoxon’s signed rank test or Student t-test for continuous variables with a non- or normal distribution, and McNemar’s test for paired categorial parameters) served exclusively for the post hoc evaluation of treatment-related changes at the end of treatment versus baseline and not for the confirmation of predefined hypotheses. All relevant test procedures were evaluated with a significance level of 0.05 and test procedures were adapted to the scale level of the variables to be analyzed. Since all the test procedures were exploratory in nature, the use of biometric correction procedures for their repeated application was dispensed. Complementary effect size analyses for repeated (pre- to posttest) measures were performed according to the recommendations of Morris and DeShon to gain further insights into the clinical relevance of observed treatment effectsCitation36,Citation37.

Safety and tolerability analyses were carried out under consideration of frequency/spectrum of reported DRAEs, and DRAE-related treatment discontinuations.

Primary endpoint

Beyond descriptive data evaluations, a primary endpoint analysis has been performed on patients who reported a beneficial effect in response to PRI with respect to (a) pain intensity (PIX) and (b) pain-related disabilities in daily life (mPDI), each with an absolute improvement equal to or even greater than the minimal clinical important difference (MCID) and/or ≥50%, and who reported (c) an improvement in their overall wellbeing (as assessed via the MQHHF), each at end-of-treatment versus baseline. Patients who fulfilled all of the mentioned efficacy response criteria (a–c) without any PRI-related DRAEs were classified as complete responders, those who fulfilled at least one efficacy criterium without any DRAEs were rated as partial responders, and the remaining ones (i.e. those who fulfilled none of the efficacy criteria and/or who reported at least one DRAE in response to PRI) were rated as non-responders.

Due to the exploratory nature of this study, no a priori hypotheses were made for this primary endpoint analysis.

Ethics

This non-interventional data evaluation followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant national and regulatory requirements. The study concept has been approved by the ethics committees of the German Pain League and registered in the electronic data base of the European Medicine Agency for non-interventional studies (ENCEPP: EUPAS identifier 45869). Both, patients as well as physicians provided written informed consent prior participation in the GPeR and agreed to the use of their anonymized data for health care research purposes. All analyses based exclusively on completely anonymized data to comply with national guidelines on protection of data privacy and the EU General Data Protection Regulation and all analytical procedures were defined in a statistical analysis plan prior start of data evaluation. The use of the electronic documentation platform iDocLive and access to the GPeR was free of charge for members of the German Pain Association as well as for any patients regardless of their insurance status.

Results

Patient disposition

Between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2020, 121,803 patients actively participated in the GPeR and reported information about their individual pain problems and their response to treatment (see ). Of these, 1133 patients (0.9% of the registry population) suffered from MRP and reported information on a treatment with PRI, which were the starting point of the present analysis.

Patient characteristics

Demographics and baseline data characterized a cohort of patients suffering predominantly from acute MRP (see and ). Mean age (±SD) was 53.9 ± 11.8 (median: 54, range: 18–85) years and 54.5% (n = 617) of patients were female. Average pain duration was 20.3 ± 77.4 (median: 6, range: 2–1679) days, with 691 patients (61.0%) of the sample reporting a pain duration of one week or less prior baseline. About 1073 patients (94.7%) graded their pain severity as stage 1 or 2 according to the von Korff grading scale, and 1020 patients (90.0%) were classified to suffer from acute pain due to the Mainz Pain Staging System. On average, patients reported a pre-treatment history of 1.8 ± 0.9 (median: 2, range: 1–5) analgesic medications and five out of 10 patients (51.8%) recorded the use of two or more pain treatments prior PRI. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were the most prevalently used analgesics, taken by 83.7% of patients, followed by nonopioid analgesics (NOPA, 53.2%), mild opioid analgesics (MOA, 9.5%), antidepressant drugs (ADD; 4.9%), antiepileptic drugs (AED, 2.4%), and strong opioid analgesics (SOA, 1.2%). With 16.4% (n = 186), less than two of 10 patients received or used a non-pharmacological pain treatment. Of the patients who received such a treatment, physiotherapy was the most frequently mentioned therapy procedure (11.4%), followed by transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS, 4.8%), massage (4.2%), physical measures (3.9%), and others.

Table 1. Patient demographics.

Table 2. Baseline pain characteristics.

Concomitant disorders were frequent and affected 83.1% of patients (n = 941). All in all, patients recorded 1.5 ± 1.1 (median: 1, range: 0–5) concomitant diseases, most prevalently allergies (20.6%) and cardiovascular diseases (19.8%).

Primary reason for treatment with PRI was MRP of the (lower) back (43.2%), hip/leg (26.4%), shoulder/neck (21.1%), and arm (2.0%). In 46 patients (4.1%), no information was provided on the location of the muscle pain, and in 36 cases (3.2%) PRI was used to treat a primary muscle disease.

Baseline scores for lowest (LPI), average (API), and highest (HPI) 24-h pain intensities were 19.3 ± 19.0 (median: 12), 62.8 ± 12.0 (median: 60), as well as 79.8 ± 15.9 (median: 84) mm VAS, and the corresponding 24 h. pain intensity index (PIX) score was 54.0 ± 10.2 (median: 52) mm VAS (see ). Percentage of patients with a moderate/strong/extreme MRP (corresponding to PIX scores 31–50/51–70/>70 mm VAS) at baseline was 36.4/55.4/7.3%.

Pain-related disabilities with respect to daily life activities were recorded to be 61.3 ± 15.8 (median 63) mm VAS on average, and 74.7% of patients (n = 847) presented with mPDI scores ≥50 mm VAS, indicating strong restrictions. Reported degree of disability varied according to the life domain evaluated: strongest impairments were reported for the domain of homework/occupation (75.8 ± 21.6; median 81 mm VAS), whereas lowest impairments were found for the area of self-care and personal maintenance (37.6 ± 25.8, median 31 mm VAS). Percentage of patients with moderate/strong/extreme pain-related disabilities in daily life (corresponding to mPDI scores 31–50/51–70/>70 mm VAS) at baseline were 22.8/43.3/31.4%.

As a consequence of the aforementioned pain and pain-related impairments, the overall well-being of the patients evaluated in this study was significantly impaired. The average MQHHF score was 1.9 ± 1.0 (median 2) and the percentage of patients with moderate (average NRS5 score ≤3.0) or even severe impairments (≤1.5) was 49.3 respective 39.9%.

Dosage and duration of treatment

On average patients reported a treatment with 2.6 ± 0.6 (median 3, range 0.5–4.5) tablets per day, corresponding to a daily dose of 7.8 ± 1.8 (median 9, range 1.5–13.5) mg PRI. Average treatment duration was 12.0 ± 10.2 (median 7, range 3–63) days, and the corresponding cumulative dose exposure was 96.3 ± 89.1 (median: 60, range: 6.0–567) mg PRI on average ().

Treatment response

Pain intensity and pain-related disability

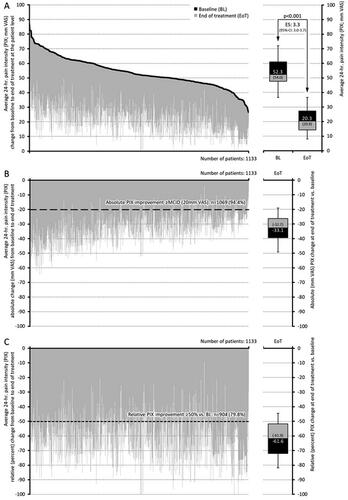

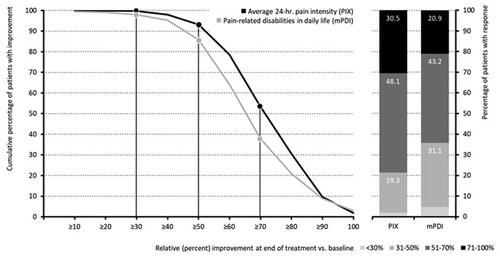

The add-on treatment with PRI led to a significant decrease in pain intensity (see and ). The average 24-h pain intensity index (PIX) improved from 54.0 ± 10.2 (median: 52.3) mm VAS at baseline to 20.9 ± 9.0 (median: 20.3) mm VAS at end of treatment (p < .001), translating into an absolute improvement of −33.1 ± 9.4 (median −32.7) mm VAS (p < .001; effect size: 3.3, 95% CI: 3.0–3.7). Relative improvement was independent of baseline pain intensity and reported to be −61.6 ± 14.5 (median −61.9) percent versus baseline. The percentage of patients who reported either an absolute improvement equal to or even greater than the minimal clinical important difference (MCID, i.e. ≥20 mm VAS) or a relative improvement ≥50 percent versus baseline was 94.4% (n = 1069) and 79.8% (n = 904) respectively. In line with this, the proportion of patients who reported no or only low-intensity pain increased from 0.9% (n = 10) at baseline to 83.6% (n = 947; p < .001 for all comparisons).

Figure 2. Change from baseline to end of treatment for the average 24-h pain intensity (PIX). (a) The black lines represent baseline values for each individual patient, sorted by severity. Individual grey lines represent the change from baseline at end of treatment for each individual patient. The pre (baseline; BL) and end of treatment (EoT) boxplots show median (middle horizontal line in the box), and quartiles 25% and 75% (bottom and top lines of the box); whiskers correspond to the 5–95% quantiles; numbers given in boxplots are median (mean). (b, c) Show the absolute (mm VAS) and relative (percent) changes versus baseline for each individual, sorted by severity (i.e. identical to figure a) and boxplots show the corresponding median, 25–75%, and 5–95% quantiles as well as median (mean). Abbreviations. PIX, pain intensity index; VAS, visual analogue scale; CI, confidence interval; BL, baseline; EoT, end of treatment; ES, effect size; 95% CI: 95 percent confidence interval.

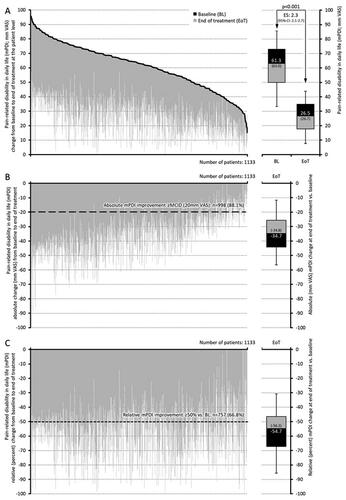

Figure 3. Change from baseline to end of treatment for pain-related disabilities in daily life (mPDI). (a) The black lines represent baseline values for each individual patient, sorted by severity. Individual grey lines represent the change from baseline at end of treatment for each individual patient. The pre (baseline; BL) and end of treatment (EoT) boxplots show median (middle horizontal line in the box), and quartiles 25% and 75% (bottom and top lines of the box); whiskers correspond to the 5–95% quantiles; numbers given in boxplots are median (mean). (b,c) Show the absolute (mm VAS) and relative (percent) changes versus baseline for each individual, sorted by severity (i.e. identical to figure a) and boxplots show the corresponding median, 25–75%, and 5–95% quantiles as well as median (mean). Abbreviations. mPDI, modified pain disability index; VAS, visual analogue scale; CI, confidence interval; BL, baseline; EoT, end of treatment; ES, effect size; 95% CI: 95 percent confidence interval.

Figure 4. Response (percent improvement between baseline and end of treatment) to pridinol. Notes: Left panel: cumulative proportion of patients with percent improvement for the average 24-h pain intensity (black) and the pain-related disabilities in daily life (grey). Right panel: categorial groups of patients with defined degrees of response to pridinol at end of treatment versus baseline.

Table 3. Response to treatment.

In parallel treatment with PRI induced a significant improvement with respect to pain-related disabilities of daily life activities. The mPDI score improved from baseline to end of treatment from 61.3 ± 15.8 to 26.5 ± 11.3 mm VAS, according to an absolute/relative improvement of −34.8 ± 13.8/−56.8 ± 17.2 (median −34.7/−54.7) mm VAS/percent (p < .001; effect size: 2.3, 95% CI: 2.1–2.7). Proportions of patients with an absolute/relative improvement ≥ MCID/50% versus baseline were 88.1/66.8% (n = 998/757), and the percentage of patients with mild or even no disability increased from 2.5% (n = 28) at baseline to 60.1% (n = 681) at the end of treatment (p < .001 for all comparisons and changes).

shows a correlation analysis of the absolute (mm VAS) improvements of pain intensity and pain-related disabilities as a consequence of the analgesic medication with PRI. Treatment effects on both parameters are closely related – as proven by the coefficient of determination (r2) score >0.8, suggesting that the effects of PRI go beyond purely symptomatic analgesia.

Figure 5. Scatterplot of the improvements for the average 24-h pain intensity index (PIX; x-axis) and the pain-related disabilities in daily life (mPDI; y-axis) at the end of treatment [each given as absolute (mm VAS) improvement versus baseline]. Notes: Dotted diagonal shows the linear correlation trend (incl. the coefficient of determination R2). Abbreviations. PIX, pain intensity index; mPDI, modified pain disability index; VAS, visual analogue scale.

![Figure 5. Scatterplot of the improvements for the average 24-h pain intensity index (PIX; x-axis) and the pain-related disabilities in daily life (mPDI; y-axis) at the end of treatment [each given as absolute (mm VAS) improvement versus baseline]. Notes: Dotted diagonal shows the linear correlation trend (incl. the coefficient of determination R2). Abbreviations. PIX, pain intensity index; mPDI, modified pain disability index; VAS, visual analogue scale.](/cms/asset/c333b89b-5020-4d2f-bd53-02f08ddf1ffa/icmo_a_2077579_f0005_b.jpg)

Analyses of the differential efficacy of PRI showed no evidence of a relevant dependence of the extent of the observed pain relief or the reduction of pain-related impairments from the individual pre-existing duration of complaints. Corresponding subgroup analyses showed no significant differences between patients with different duration of symptoms, neither for the parameter pain relief (PIX; p = .836), nor for the reduction of pain-related impairments in everyday life (mPDI: p = .692).

Overall wellbeing

Based on the analysis of the MQHHF, treatment with PRI resulted in significant improvement of the overall wellbeing of patients in this study versus baseline. MQHHF scores increased from 1.9 ± 1.0 at baseline to 2.5 ± 1.0, and percentages of patients with minor or without any impairments of their overall wellbeing increased from 10.8% (n = 122) at baseline to 28.8% (n = 326) at end of treatment (p < .001; effect size 0.6, 95% CI: 0.5–0.7). All in all, overall wellbeing improved with PRI in 817 patients (72.1%).

Analyses of the dependency of the documented changes in overall well-being from the individual pre-existing duration of symptoms showed no evidence of a significant difference in response between patients with different pain duration (p = .716).

Concomitant analgesic medication

The add-on treatment with PRI allowed a significant decrease of analgesic medications (see ). Average ± SD (median) number of analgesic and co-analgesic medications used at baseline versus end of treatment with PRI decreased from 1.8 ± 0.9 (2) to 1.1 ± 1.1 (1; p < .001). With 473 (41.7%), 4 out of 10 patients reported the termination of at least one other analgesic medication in response to PRI, and 349 patients (30.8%) even reported the complete termination of any other pain medication used prior onset of PRI).

Table 4. Changes in analgesic medication.

Safety and tolerability

Overall, PRI treatment was well tolerated and safe. As shown in , only 6.2% of patients (n = 70) documented a DRAE of which nine events (0.8%) led to a premature termination of the treatment. Most prevalent PRI-related DRAEs were headaches, reported by 1.4% (n = 16), followed by dizziness, nausea, abdominal pain, and somnolence (each in 0.7%), peripheral circulatory response (0.5%), hypotension (0.4%), tachycardia, dry mouth, and weakness (each 0.3%), as well as restlessness (0.2%). Dizziness was the DRAE most frequently followed by termination of treatment (n = 3), followed by peripheral circulatory response (n = 2), headaches, hypotension, tachycardia, and restlessness (with each n = 1).

Table 5. Drug-related adverse events.

Adverse drug reactions manifested between the 3rd and 28th day of treatment, affected both women and men equally, and were independent of patient age. However, the average daily dose of PRI in patients who had to discontinue treatment early due to an adverse event was significantly higher than that of patients with DRAEs who were able to continue treatment. (3.7 ± 0.7 vs. 3.2 ± 0.6 mg; p = .045). And both doses, in turn, were significantly higher than those of patients with no side effects (2.6 ± 0.6 mg; p < .001).

Primary endpoint

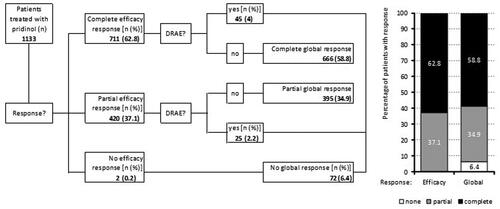

summarizes the results of the primary endpoint analysis. Overall, 711 patients (62.8%) fulfilled the definition of a complete efficacy response at the end of their PRI treatment [i.e. they reported (a) either an absolute improvement ≥ MCID and/or a relative improvement ≥50% vs. baseline for pain intensity and pain-related disabilities, as well as (b) an improvement in their overall wellbeing], 420 patients (37.1%) reported a partial response (i.e. they fulfilled at least one of the aforementioned efficacy criteria), and only two patients (0.2%) were classified as non-responder (i.e. they failed to fulfill any of the described efficacy criteria).

Figure 6. Summary of efficacy and tolerability information relevant for the primary endpoint calculation. DRAE: drug-related adverse event.

Of the 711/420 patients with a complete/partial efficacy response, 45/25 (4.0/2.2%) documented an adverse drug reaction due to PRI, resulting in a total of 72 patients (6.4%) with a global nonresponse (when combined with the two patients without any evidence of efficacy mentioned above), 395 patients (34.9%) with a partial, and 666 (58.8%) with a complete global response.

Discussion

This exploratory real-world cohort study of de-identified data of the German Pain e-Registry on the efficacy and tolerability of pridinol – the worldwide largest non-interventional study on this component – evaluated 1133 patients with predominantly acute MRP, who reported a moderate to severe pain intensity as well as significant pain-related restrictions with respect to all dimensions of their daily life activities despite analgesic treatment (predominantly with NSAIDS and NOPA). In this patient cohort, treatment with PRI over a variable length of 3 to 63 days was generally well tolerated and followed by a significant and clinically relevant improvement of pain intensity, pain-related disabilities, and overall wellbeing in the majority of treatment cases. Only 6.4% of patients who reported on their experience with PRI were classified as global treatment failures (either due to an inadequate analgesic response or DRAEs), whereas 34.9% reported a partial and 58.8% even a complete global response without any DRAEs.

This effectiveness reported by patients under real-world conditions contrasts with the recommendations for the use of antispasmodics as published in current guidelinesCitation10,Citation11 but reflects the experienced popularity of the agent among German physicians – especially in view of the insufficient availability of appropriate (i.e. causally effective) alternativesCitation25. In our study, pridinol was prescribed exclusively to patients who had already received symptomatic pain therapy predominantly with NSAIDs (83.7%), but had not shown sufficient effect on these analgesics, although NSAIDs are recommended as first-line option in current guidelines for the treatment of acute MRP.

In addition, three of four patients in our study cohort treated with NSAIDs (74.1%, n = 702) reported the presence of at least one, 43.7% even the simultaneous presence of two or more of known risk factors for the use of these agents (i.e. older age ≥65 years, history of gastrointestinal-bleeding or peptic ulcer, cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, renal failure, cirrhotic liver disease, use of aspirin or other nonaspirin antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants, corticosteroids or serotonin reuptake inhibitors)Citation38, so the documented use of NSAIDs in this patient population has been not only ineffective but also dangerous.

In view of this, the tolerability and efficacy observed in our study on a short-term treatment with PRI appear surprisingly good and (especially against the background of the aforementioned risk factors and the purely symptomatic approach of NSAIDs) at least raise questions regarding the recommendations given in current treatment guidelines, which are predominantly based on the results of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Formally, the data based on these RCTs indeed support the current positioning of NSAIDs as first-line agents for the treatment of acute muscular pain. However, from a practical point of view the insufficient efficacy of NSAIDs in non-inflammatory nociceptive pain (such as MRP), their risks of use in elderly and comorbid patients, and the subsequent limitations in terms of dosing (lowest effective dose) and duration of treatment (shortest duration of time) cause major problems in daily practice, resulting in both the need and the ongoing search for (better? or causally?) effective and, above all, safer alternatives.

Based on the analyses of the documented adverse drug reactions and the additional analyses carried out by us regarding possible hidden indications of treatment-related tolerability problems, no new information on previously unknown or frequently occurring tolerability problems was found in comparison to the current product descriptions. Overall, treatment with pridinol proved to be (very) well tolerated with few side effects – which should be emphasized as quite positive news in view of the known mechanism of action (inhibition of muscarinic M1 acetylcholine receptors), since acetylcholine receptor antagonists otherwise tend to be among the less well tolerated agents with a considerable potential for side effects (especially in elderly). This favorable side effect profile is confirmed in a current review of the so-called acetylcholine burden score of various active substances, in which pridinol is attributed an overall low risk with regard to the development of acetylcholinergic side effectsCitation39.

Based on the present results of our analysis of real-world data on efficacy and tolerability, there are promising prospects for a wider use of pridinol for the relief of MRP. Unfortunately, the number of published studies conducted with orally administered PRI in patients with MRP is limited. A corresponding web-based literature research identified only one "controlled" study in MRP patients on PRI as oral add-on therapy (in addition to physical measures) for up to four weeks, published in German in 1975 in an orthopedic journal without peer reviewCitation40 which reports a significantly better analgesic effect for patients who received PRI in comparison to those without (p < .05). However, the methodological quality of this study is – for a number of reasons (i.e. no demographic and baseline data, unclear randomization process, insufficient information on study procedures and control mechanisms, no data on concomitant analgesic medication or treatment discontinuations, etc.) – questionable and the data reported far too incomplete to comprehend the results independently.

Due to the lack of current data from methodologically valid and numerically sufficiently large, controlled studies, the reported analyses on the efficacy and tolerability of PRI under conditions of routine care allow only a superficial insight into the effects actually to be expected (and causally attributable to the evaluated active substance). This does not fundamentally question the therapeutic rationale for its use, nor the desired effects or undesired side effects observed, but puts them into perspective to the extent that they urgently require some kind of confirmation (ideally through a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial or at least by a matched parallel cohort study under everyday conditions).

Strengths and limitations

Since this evaluation is based on a retrospective analysis of observational and open-label real-world data gathered via an electronic treatment registry as part of daily routine care, several limitations should be considered.

The most obvious (and in this case also the most important) limitation of this analysis is the lack of a control (active or placebo) group, which makes it impossible to differentiate between effects that are the direct consequence of the treatment under evaluation versus those that are related to other unrecognized, and uncontrolled factors. However, the fact that pridinol is not legally subject to patent protection makes it considerably more difficult to conduct a prospective randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Furthermore, it is foreseeable that the duration of such a study with pridinol contrasts the urgently needed timely clarification of the benefits and risks of its current use. For this reason, controlled retrospective analyses of comparable patient collectives using established treatment registries (such as the GPeR) would certainly be a good [and especially fast(er)] alternative.

High spontaneous remission of acute myofascial pain is – especially for an evaluation relying on uncontrolled routine data like the present one – a significant limitation. However, despite intensive efforts, we have not been able to find any specific, usable references to data on the extent of spontaneous remissions that would allow a comparison with the data presented by us. Because of methodological differences, data on the placebo response from controlled studies cannot really be used, and the otherwise rumored speculations on the (high) extent of spontaneous remission are neither scientifically comprehensible nor applicable to our data, so that we cannot make any statements in this regard.

In principle, there is also a certain risk that the available data are subject to a selection bias due to their generation via the online documentation service iDocLive and that the evaluations based on them are not representative. However, the GPeR network with its 840 pain specialists, 852 physicians, and 2733 non-medical pain specialists mirrors the whole spectrum of medical and associated disciplines involved in pain management. Furthermore, the 239 interdisciplinary pain centers are uniformly distributed among Germany, representing about 25% of all pain facilities in the country, with different sizes and settings (urban, rural), which minimizes the risk of geographical or other systemic patient selection biases.

Patient selection and treatment decisions were based solely on the discretion of the physicians and their clinical judgments, eliminating any form of selection bias as far as possible. Nevertheless, it should be considered that MRP patients treated by these specialists may differ from patients who consult general practitioners or other primary care physicians.

Another potential limitation of this analysis was the inclusion of multiple MRP etiologies resulting in a considerable data heterogeneity – an issue that can be easily solved within the already mentioned (and recommended) controlled studies or registry analyses by appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria.

A formal issue interfering with common Good Clinical Practice (GCP) standards for conducting clinical trials and non-interventional studies is that none of the patient-reported data derived from the GPeR for evaluation purposes like this study allowed a confirmation via paper records or other sources, laboratory results or treatment schedules, simply due to the fact that the direct electronic data entry performed under the conditions of daily routine care does not provide evaluable materials for independent source data verification processes. Moreover, German data protection laws, the EU General data protection regulation, and the GPeR standard operating procedures require to perform all analyses with completely anonymized data sets only, which excludes any possibilities for backward tracing or the identification of individual patients, pain management centers, or pain specialists.

On the other hand, this special design is a unique strength of our analysis, as it focuses almost exclusively on patient-relevant and especially patient-reported outcomes, sampled as part of an electronic routine data registry established to improve patient care under real-life conditions.

Limitations with respect to the range of variables collected was – in comparison to most other routine data collecting systems and registries – not really a problem, as most of the information generated by administrative and clinical GPeR processes was based on standardized documentation tools (e.g. German Pain Questionnaire and German Pain Diary) mutually developed, agreed and recommended for routine use by respective medical associations in Germany (the German Pain Association and the German Pain Society) and the German Pain League (Germanys largest umbrella group for self-regulating communities of pain and palliative care patients) in 2006Citation30,Citation31. Both tools cover a broad range of validated self-assessment instruments sensitive for baseline as well as follow-up evaluations during the longitudinal course of a pain treatment and fulfil all official requirements for a quality assured standard documentation tool for pain medicine as defined by the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance PhysiciansCitation32.

The most important factors in favor of this registry-based treatment evaluation are that in contrast to usual studies (interventional or not), neither physicians nor patients received any type of compensation for their data collection activities. All data recorded via the registry were only entered to improve patient-physician interaction – two factors eliminating any data entry motivated by financial incentive. GPeR participation and the disposal of the online documentation tool iDocLive is complimentary for physicians who are members of the German Pain Association and free of charge for all patients – irrespective of their health insurance coverage.

Conclusion

Although acute muscular pain has a high spontaneous remission rate and usually passes on its own, many patients require a temporary pharmacotherapy to alleviate both pain and accompanying physical impairments. NSAIDs are listed as first-line options in current guidelines; however, their effects are limited in noninflammatory muscular pain, and their use associated with considerable risks for adverse effects. Therefore, rational (i.e. causally effective) and especially better tolerated (as well as safer) treatment alternatives are urgently needed. Based on the present analysis of de-identified routine data of the GPeR, a short-term treatment with the muscle relaxant pridinol over a period of up to nine weeks seems to be an effective and well-tolerated treatment option for patients with acute myofascial pain – even though current data from methodologically high-grade controlled studies are still lacking to independently confirm these effects.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The concept for this evaluation of routine data provided by the German Pain e-Registry was developed by M.A.U. at the Institute of Neurological Sciences (IFNAP) on behalf of the German Pain Association (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schmerzmedizin, DGS) and the German Pain League (Deutsche Schmerzliga, DSL) and its realization has been funded by an unrestricted scientific grant from Strathmann GmbH & Co. KG, Germany. Neither Strathmann as a company, nor any of its employees exerted any influence on the data acquisition, the conduct of this analysis, or on the interpretation and publication of the results.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

M.A.U., G.H.H.M.-S., and J.H. are physicians and independent of any significant/relevant financial or other relationship to the sponsor, except for minor reimbursements for occasional lecture or consulting fees. All are current (M.A.U., J.H.) or former (G.H.H. M.-S.) honorary members of the management board of the German Pain Association, M.A.U is also honorary member of the management board of the German Pain League.

The German Pain e-Registry is hosted by an independent contract research organization by order of the German Pain Association and under control of the Institute of Neurological Sciences and collects standardized real-world data from daily routine medical care since January 2000.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript to be published. M.A.U. takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to the finished article.

Acknowledgements

Preliminary results of this analysis have been presented at the annual Congress of the German Chapter of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), 21–23 October, 2021, Mannheim, Germany.

Notes

i iDocLive is a registered trademark of O.Meany-MDPM GmbH, Nürnberg, Germany.

References

- GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–1259.

- Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, et al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(6):2028–2037.

- von der Lippe E, Krause L, Porst M, et al. Prävalenz von rücken- und nackenschmerzen in deutschland. Ergebnisse der Krankheitslast-Studie BURDEN 2020. J Health Monit. 2021;6(S3):2–14.

- O’Sullivan P. Diagnosis and classification of chronic low back pain disorders: maladaptive movement and motor control impairments as underlying mechanism. Man Ther. 2005;10(4):242–255.

- Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(5):363–370.

- O’Sullivan P. It’s time for change with the management of non-specific chronic low back pain. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(4):224–227.

- National Institute of Health. Low Back Pain Fact Sheet. 2019; [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/patient-caregiver-education/fact-sheets/low-back-pain-fact-sheet.

- O’Sullivan PB, Caneiro JP, O’Sullivan K, et al. Back to basics: 10 facts every person should know about back pain. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(12):698–699.

- Di Iorio D, Henley E, Doughty A. A survey of primary care physician practice patterns and adherence to acute low back problem guidelines. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(10):1015–1021.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Clinical efficacy assessment subcommittee of the American College of Physicians; American College of Physicians; American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478–491.

- Bundesärztekammer (BÄK), Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftli-chen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF). Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Nicht-spezifischer Kreuzschmerz – Langfassung, 2. Auflage. Version 1. 2017; [cited 2002 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.leitlinien.de/themen/kreuzschmerz/2-auflage.

- Schers H, Braspenning J, Drijver R, et al. Low back pain in general practice: reported management and reasons for not adhering to the guidelines in The Netherlands. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50(457):640–644.

- Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(11):2791–2803.

- Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Schiller M, et al. Real-world practice patterns, health-care utilization, and costs in patients with low back pain: the long road to guideline-concordant care. Spine J. 2011;11(7):622–632.

- Bishop PB, Wing PC. Knowledge transfer in family physicians managing patients with acute low back pain: a prospective randomized control trial. Spine J. 2006;6(3):282–288.

- Piccoliori G, Engl A, Gatterer D, et al. Management of low back pain in general practice – is it of acceptable quality: an observational study among 25 general practices in South Tyrol (Italy). BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:148.

- Williams CM, Maher CG, Hancock MJ, et al. Low back pain and best practice care: a survey of general practice physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(3):271–277.

- Di Gangi S, Pichierri G, Zechmann S, et al. Prescribing patterns of pain medications in unspecific low back pain in primary care: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(7):1366.

- Back-Report Switzerland. 2020. Rheumaliga Schweiz Juli 2020; [cited 2022 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.rheumaliga.ch/assets/doc/CH_Dokumente/blog/2020/rueckenreport-2020/Rueckenreport-2020.pdf.

- [cited 2022 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.bfarm.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Arzneimittel/Pharmakovigilanz/PSUSAS/s-z/tizanidin_beschluss_cmdh.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2.

- [cited 2022 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/press-release/european-medicines-agency-recommends-restricting-use-tolperisone-medicines_en.pdf.

- [cited 2022 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/press-release/recommendation-suspend-tetrazepam-containing-medicines-endorsed-cmdh_en.pdf.

- [cited 2022 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/referral/prac-recommends-marketing-authorisation-painkiller-flupirtine-be-withdrawn_en.pdf.

- Pridinol. Myopridin® 3 mg tablets (Strathmann) summary of product characteristics, last updated Aug 2019.

- Pridinol – central and peripheral muscle spasms, lumbalgia, torticollis and general muscle pain. Article in German; [cited 2022 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.kbv.de/media/sp/WirkstoffAktuell_4-21_Pridinol.pdf.

- GKV-Arzneimittelindex im Wissenschaftlichen Institut der AOK (WIdO): Deutsches Institut für Medizinische Dokumentation und Information (DIMDI) (Hrsg.): Anatomisch-therapeutisch-chemische Klassifikation mit Tagesdosen. Amtliche Fassung des ATC-Index mit DDD-Angaben für Deutschland im Jahre 2021. Berlin: DIMDI, 2021.

- Forth W, Henschler D, Rummel W, et al. [Allgemeine und spezielle pharmakologie und toxikologie], 6th edition. Mannheim, Leipzig, Wien, Zurich: BI‐Wissenschaftsverlag; 1992.

- Stock B, Spiteller G. Metabolism of antiparkinson drugs. An example of competitive hydroxylation. Arzneimittelforschung. 1979;29(4):610–615.

- Richter M, Donath F, Wedemeyer RS, et al. Pharmacokinetics of oral pridinol: results of a randomized, crossover bioequivalence trial in healthy subjects. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;59(6):471–477.

- Deutsche Schmerzgesellschaft. Deutscher Schmerzfragebogen [German pain questionnaire]; [cited 2022 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.dgss.org/deutscher-schmerzfragebogen. (German).

- Deutsche Schmerzgesellschaft. Handbuch zum Deutschen Schmerzfragebogen [Manual for the German pain questionnaire]; [cited 2022 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.dgss.org/fileadmin/pdf/12_DSF_Manual_2012.2.pdf. (German).

- Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung. Qualitätssicherungsvereinbarung zur schmerztherapeutischen Versorgung chronisch schmerzkranker Patienten gem. § 135 Abs. 2 SGB V. (Qualitätssicherungsvereinbarung Schmerztherapie); [cited 2022 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.kbv.de/media/sp/Schmerztherapie.pdf. (German).

- Tait RC, Chibnall JT, Krause S. The pain disability index: psychometric properties. Pain. 1990;40(2):171–182.

- Basler HD. Marburger fragebogen zum habituellen Wohlbefinden – Untersuchung an patienten mit chonischem schmerz [the marburg questionnaire on habitual health findings – a study on patients with chronic pain]. Schmerz. 1999;13(6):385–391. German.

- Überall MA. DGS-PraxisRegister schmerz. Von der pflicht zur kür – standardisierte dokumentation in der schmerzmedizin. Schmerzmed. 2016;32(4):36–56.

- Morris SB, DeShon RP. Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):105–125.

- Morris SB. Estimating effect sizes from pretest-posttest-control group designs. Organizational Res Meth. 2008;11(2):364–386.

- Lanas A, Garcia-Tell G, Armada B, et al. Prescription patterns and appropriateness of NSAID therapy according to gastrointestinal risk and cardiovascular history in patients with diagnoses of osteoarthritis. BMC Med. 2011;9:38.

- Ramos H, Moreno L, Pérez-Tur J, et al. CRIDECO anticholinergic load scale: an updated anticholinergic burden scale. Comparison with the ACB scale in Spanish individuals with subjective memory complaints. J Pers Med. 2022;12(2):207.

- Beyeler J. Zur therapie des paravertebralen hartspanns mit lyseen. Orthopädische Praxis. 1975;(XI):796.