Abstract

Objective

The objective of this post-hoc analysis was to assess the impact of lurasidone monotherapy on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in adults with bipolar depression.

Methods

Data were analyzed from a 6-week randomized, double-blind (DB), placebo-controlled trial of lurasidone monotherapy (NCT00868699) and a 6-month open label extension (OLE; NCT00868959). Patients who received lurasidone monotherapy or placebo during the DB trial were eligible to continue or switch to lurasidone monotherapy during the OLE. The 16-item Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-Short Form (Q-LES-Q-SF) was collected at DB baseline, DB week 6/OLE baseline, OLE month 3, and OLE month 6. Effect size (ES) and mean changes from baseline were reported for Q-LES-Q-SF total and item scores during the DB trial and OLE, respectively.

Results

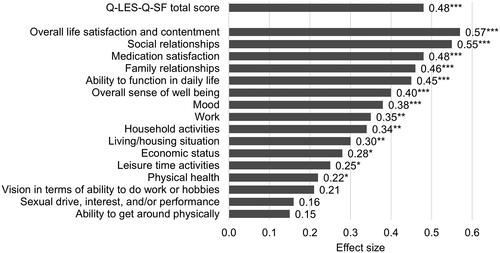

Of 485 patients in the DB trial (lurasidone monotherapy: n = 323; placebo: n = 162), 316 patients continued or switched to lurasidone monotherapy during the OLE. Significant improvements in Q-LES-Q-SF scores in lurasidone vs. placebo were reported for 13 of 16 items (all p < .05) at DB week 6. The greatest improvements were overall life satisfaction (ES = 0.57), social relationships (0.55), medication satisfaction (0.48), family relationships (0.46), and ability to function in daily life (0.45, all p < .001). Improvements in Q-LES-Q-SF total and item scores were sustained at OLE month 6.

Conclusions

Treatment with lurasidone provided a significant improvement across HRQoL items including overall life satisfaction, social and family relationships, medication satisfaction, and ability to function in daily life. Improvements were sustained during the 6-month OLE.

Introduction

Bipolar disorder is a chronic mood disorder characterized by recurring manic or hypomanic episodes alternating with depressive episodesCitation1. The annual prevalence of the bipolar disorder among adults in the US is 2.8%Citation2. Patients with bipolar I disorder spend, on average, 70% of the symptomatic time in a depressed state (bipolar depression)Citation3. Mental disorders, including bipolar disorders, are a substantial burden to disability worldwideCitation4.

Bipolar depression is characterized by depressed mood and/or anhedonia and other symptoms such as changes in sleep, appetite/weight, energy, psychomotor activity, concentration, thought content (guilt and worthlessness), and suicidal intentCitation5. Depressive symptoms are often associated with decreased functioning in patients with bipolar disorderCitation6. Both depressive symptoms and functional impairment contribute to decreased health-related quality of life (HRQoL)Citation6,Citation7.

Five drugs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of bipolar depression in adults: lurasidone, cariprazine, olanzapine-fluoxetine, quetiapine, and most recently lumateperoneCitation1,Citation8. The placebo-controlled clinical trials and/or extensions for lurasidone, lumateperone, and quetiapine included HRQoL assessment as a secondary outcome using the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-Short Form (Q-LES-Q-SF), a commonly used assessment of HRQoL and well-beingCitation9–12.

The Q-LES-Q-SF total score for lurasidone has been previously reportedCitation9,Citation12. However, scores for individual items provide a more detailed view of the impact of treatment effects on patients’ lives. The purpose of this post-hoc analysis was to evaluate the effect of lurasidone monotherapy on the individual items of Q-LES Q-SF at both DB week 6 and OLE month 6.

Methods

Data source

Data from the 6-week randomized, double-blind (DB), placebo-controlled trial of lurasidone monotherapy (20–60 mg/day or 80–120 mg/day) for the treatment of bipolar depression (NCT00868699) and the 6-month open label extension (OLE; 20–120 mg/day) (NCT00868959) were analyzed to assess the impact of lurasidone on HRQoL. The analysis of the DB data used the intention-to-treat population, and the analysis of the OLE data used the safety population. The details of the DB trial and OLE have been previously publishedCitation12,Citation13.

DB trial participants were adults (18–75 years old) with bipolar I disorder who were experiencing a major depressive episode (DSM-IV-TR criteria, ≥4 weeks and <12 months in duration), with or without rapid cycling, without psychotic features, and with a history of at least one lifetime bipolar manic or mixed manic episode who were treated in an outpatient settingCitation13. A Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score ≥20 and a Young Mania Rating Scale score ≤12 were required at both screening and baselineCitation13. Exclusion criteria were a decrease of ≥25% in MADRS total score between screening and baseline; a score ≥4 on MADRS item-10 score (suicidal thoughts) at screening or baseline; a history of nonresponse to an adequate (6-week) trial of three or more antidepressants (with or without mood stabilizers) during the current depressive episode; or a demonstrated imminent risk of suicide or injury to self, others, or propertyCitation13. Treatment with all prior psychotropic medications (e.g. antipsychotic agents, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers) was discontinued, using a washout period of at least 3 days prior to randomization in the DB trialCitation13. Treatment with anticholinergic agents, propranolol, or amantadine was permitted as needed (but not prophylactically) for movement disorders, and treatment with lorazepam, temazepam, or zolpidem (or their equivalent) was permitted during screening and for weeks 1 to 3 as needed (but not prophylactically) for anxiety or insomnia but not within 8 h of any psychiatric assessmentCitation13.

DB trial completers were eligible to enroll in the OLE if they were judged by the Investigator to be suitable for participation, were able to comply with the protocol, were not at imminent risk of suicide or injury to self or others, and had a MADRS item-10 score (suicidal thoughts) ≤3 at OLE baselineCitation12. During the OLE, patients could be treated concomitantly with benzodiazepines, mood stabilizers (e.g. lithium, Divalproex, or lamotrigine), or antidepressants at the Investigator’s discretion, but monoamine oxidase inhibitors and antipsychotic medications other than lurasidone were prohibitedCitation12. Only patients who completed the DB trial and continued (from lurasidone monotherapy) or switched (from placebo) to lurasidone monotherapy during the OLE were included in the analysis of the OLE data.

The DB trial and the OLE were approved by Institutional Review Boards at each study center. The studies were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practices guidelines and with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. An independent data and safety monitoring board reviewed and monitored both studies. All patients provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Outcomes and other variables

Q-LES-Q-SF is a patient-reported 16-item instrument that measures the degree of enjoyment and satisfaction in daily life over the past weekCitation14. Q-LES-Q-SF items consist of physical health; mood; work; household activities; social relationships; family relationships; leisure time activities; ability to function in daily life; sexual drive, interest, and/or performance; economic status; living/housing situation; ability to get around physically without feeling dizzy or unsteady or falling; vision in terms of ability to do work or hobbies; an overall sense of well-being; medication satisfaction; and overall life satisfaction and contentment. Individual items are rated on a scale from 1–5 (‘very poor’, ‘poor’, ‘fair’, ‘good’, or ‘very good’). The Q-LES-Q-SF total score is the sum of the first 14 item scores (i.e. excluding medication satisfaction and overall life satisfaction and contentment) with a higher score indicating greater satisfaction (range = 14–70). The percentage maximum possible score is calculated as the difference between the raw total score and minimum possible score divided by the difference between the maximum possible raw score and minimum possible score (=(raw total score-14)/56; range = 0–100%). The Q-LES-Q-SF was collected at DB baseline, DB week 6/OLE baseline, OLE month 3, and OLE month 6.

The MADRS total score was the primary endpoint for the DB trialCitation13. Other variables were patient demographic and clinical characteristics at DB baseline including age, sex, race, ethnicity, geographic region, age at onset of bipolar I disorder, duration of bipolar depression from the onset of current episode, and previous medications (benzodiazepines, antidepressants, mood stabilizers). Concomitant medications were reported during the DB trial (benzodiazepines) and OLE (benzodiazepines, antidepressants, mood stabilizers).

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics of patient characteristics at DB baseline included means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables and counts and proportions for categorical variables. Mean and SD of the Q-LES-Q-SF total and item scores used observed cases and were calculated at DB baseline, DB week 6/OLE baseline, OLE month 3, and OLE month 6. Least squares (LS) mean change and standard error (SE) for Q-LES-Q-SF total and item scores from DB baseline to DB week 6 were evaluated using an analysis of covariance model with fixed effects for the treatment group, pooled study center, and baseline score as covariates. Cohen’s d effect sizes (ES; small = 0.2, moderate = 0.5, large = 0.8) were also evaluated for Q-LES-Q-SF total and item scores from DB baseline to DB week 6Citation15. Among patients who continued or switched to lurasidone monotherapy during the OLE, the mean change and 95% confidence interval (CI) for Q-LES-Q-SF total and item scores from OLE baseline to OLE month 6 were calculated. Only patients with observed values at both time points were included in the mean change calculation. All analyses were conducted using SAS software v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was reported at a p-value < .05. No multiple comparison adjustments were used because of the exploratory nature of the post-hoc analysis.

Results

Patient characteristics

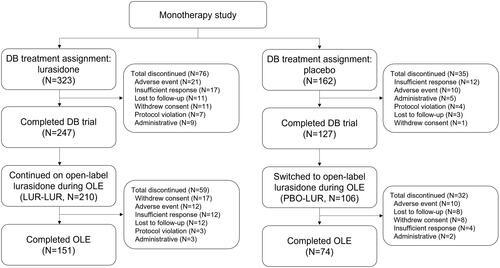

The DB trial included 323 and 162 patients in the lurasidone monotherapy and placebo groups, respectively (). Of those patients, 316 continued or switched to lurasidone monotherapy during the OLE. The average age of participants was 41.7, 41.2, and 42.0 years old at DB baseline in the lurasidone monotherapy during DB trial, placebo during DB trial, and lurasidone monotherapy during OLE cohorts, respectively (). Over half of the patients were female (lurasidone monotherapy during DB trial = 58.5%, placebo during DB trial = 53.7%, lurasidone monotherapy during OLE = 55.7%) and approximately two-thirds of patients were White (65.9%, 66.0%, 68.0%). Patients were, on average, 27.7, 27.4, and 27.8 years old at the initial onset of bipolar I disorder in the lurasidone monotherapy during DB trial, placebo during DB trial, and lurasidone monotherapy during OLE cohorts, respectively. Patients in the DB trial had previously been treated with benzodiazepines (lurasidone monotherapy during DB trial = 17.6%, placebo during DB trial = 22.2%), antidepressants (29.1%, 29.0%) and mood stabilizers (14.6%, 14.2%).

Figure 1. Patient flow diagram. Abbreviations: DB, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial; N, number of patients; OLE, open-label extension.

Table 1. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics at 6-week DB trial baseline.

6-Week DB trial

Among patients in the DB trial, 14.6% of the patients in the lurasidone monotherapy group were treated with a concomitant benzodiazepine, and 21.0% in the placebo group. The improvement in the Q-LES-Q-SF total score was significantly greater for lurasidone vs. placebo (LS mean change = 12.8 vs. 8.5, ES = 0.48, p < .001) at DB week 6 (). The LS mean change in the percentage maximum possible score was 22.8% in the lurasidone group vs. 15.2% in the placebo.

Table 2. Mean changes in Q-LES-Q-SF total and item scores during the 6-week DB trial.

Thirteen of the 16 Q-LES-Q-SF items demonstrated significantly greater improvement for lurasidone vs. placebo at DB week 6 (). The largest effect was in overall life satisfaction and contentment (ES = 0.57, p < .001) followed by social relationships (ES = 0.55, p < .001), medication satisfaction (ES = 0.48, p < .001), family relationships (ES = 0.46, p < .001), ability to function in daily life (ES = 0.45, p < .001), and overall sense of well being (ES = 0.40, p < .001). Additional significant improvements included mood (ES = 0.38, p < .001), work (ES = 0.35, p < .01), household activities (ES = 0.34, p < .01), living/housing situation (ES = 0.30, p < .01), economic status (ES = 0.28, p < .05), leisure time activities (ES = 0.25, p < .05), and physical health (ES = 0.22, p < .05).

6-Month OLE

Among patients who completed the DB trial and continued or switched to lurasidone monotherapy for the OLE, 7.6%, 5.4%, and 2.8% of patients were treated with a concomitant benzodiazepine, antidepressant, or mood stabilizer, respectively. The Q-LES-Q-SF total score continued to improve during 6 months of treatment (mean change = 5.3) (). The equivalent change in the percentage maximum possible score was 9.6%. All 16 of the Q-LES-Q-SF items improved significantly at OLE month 6. The greatest change was in mood (mean change = 0.7, percent change = 23% [=0.7/3.1]) followed by overall life satisfaction and contentment (0.6, 19% [ = 0.6/3.2]) and ability to function in daily life (0.6, 19% [ = 0.6/3.2]).

Table 3. Mean changes in Q-LES-Q-SF total and item scores among patients being treated with lurasidone monotherapy during 6-month OLE.

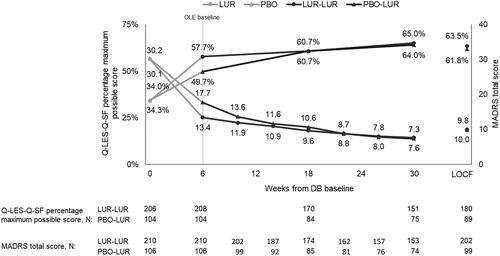

The improvement in the percentage maximum possible score was sustained during the OLE for patients who continued lurasidone monotherapy, and the score for the patients who switched to lurasidone monotherapy converged on the score for those who continued by OLE month 3 (). Improvements at OLE month 3 for patients who switched to lurasidone monotherapy were sustained through OLE month 6. A similar trend was seen for the Q-LES-Q-SF total and item scores. Improvements in the MADRS total score occurred along with improvements in the Q-LES-Q-SF percentage maximum possible score ().

Figure 3. Q-LES-Q-SF percentage maximum possible score and MADRS total score in patients who continued or switched to lurasidone monotherapy for OLE. Abbreviations: DB, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial; LOCF, last observation carried forward; LUR, lurasidone; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; N, number of patients; OLE, open-label extension; PBO, placebo; Q-LES-Q-SF, Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-Short Form. Notes: LOCF at OLE month 6 reported for comparison to mean using observed cases at OLE month 6.

Discussion

The current post-hoc analysis adds to the existing evidence by reporting individual item scores from the Q-LES-Q-SF in adults with bipolar depression who were treated with lurasidone monotherapy. At 6 weeks compared to placebo, patients treated with lurasidone had significant improvement in the Q-LES-Q total score and 13 of 16 item scores. The greatest improvements in individual items at 6 weeks were in overall life satisfaction, social relationships, medication satisfaction, family relationships, and ability to function in daily life.

Additionally, this is the first study in bipolar depression to report individual Q-LES-Q-SF items at 24 weeks. For patients continuing lurasidone or switching to lurasidone in the OLE, improvements from the OLE baseline to week 24 were reported in the Q-LES-Q total score and all 16 item scores. The greatest improvements in individual items at 24 weeks were in the mood, overall life satisfaction and contentment, and the ability to function in daily life.

Individual Q-LES-Q-SF item scores have been published for one other atypical antipsychotic indicated for bipolar depression. In a post-hoc analysis of 8-week trial data for quetiapine, significant improvement was observed in 9 of 16 items for quetiapine 300 mg/day (n = 225) and 14 of 16 items for quetiapine 600 mg/day (n = 196) at day 57Citation16. The authors reported ‘notable’ effects for household activities (300 mg/day ES = 0.26; 600 mg/day ES = 0.57), work (300 mg/day ES = 0.32; 600 mg/day ES = 0.53), daily life (300 mg/day ES = 0.25; 600 mg/day ES = 0.47), and overall sense of well-being (300 mg/day ES = 0.32; 600 mg/day ES = 0.46) (ES approximated using DigitizeIt software (DigitizeIt; Braunschweig, Germany))Citation16. Consistent with the present study, one of the highest effect sizes (approximately 0.4) for both the 300 mg/day and 600 mg/day doses of quetiapine was in social relationships. Lurasidone was further associated with significant improvements in additional items such as medication satisfaction.

Previous post-hoc analyses of the lurasidone DB trial data have focused on the Q-LES-Q-SF total score. A study using path analysis, a method to assess the causal pathways and effects of multiple variables on an outcome, reported that the effect of lurasidone on the Q-LES-Q-SF total score primarily occurs indirectly through a decrease in depressive symptomsCitation9. The minimally clinically important difference (MCID) for Q-LES-Q has been reported to be 8.9–15.6Citation17,Citation18. This suggests that the improvement in the Q-LES-Q-SF total score (LS mean change = 12.8) for lurasidone in this study was a clinically meaningful difference. Future research on the Q-LES-Q-SF could examine the relationship between individual item scores and depression symptoms as well as mixed features and anhedonia.

Lurasidone monotherapy vs. placebo significantly improved Q-LES-Q-SF items related to functions such as the ability to function in daily life and social and family relationships. Significant improvement in HRQoL related to functioning at DB week 6 could suggest a recovery beyond depressive symptom remission for patients treated with lurasidone monotherapy. Consistent with these findings, a post-hoc analysis of the same DB trial found significant improvement in functional impairment in patients treated with lurasidone monotherapyCitation19. These findings are particularly relevant as functional improvement is one of the main goals of bipolar disorder treatmentCitation20.

There were several limitations to this study. First, the Q-LES-Q-SF is a patient-reported instrument which requires patients to recall HRQoL in the past week. As such, the findings may be affected by recall bias. Another limitation of subjective HRQoL instruments is the potential for social desirability bias. Third, results may have been different if a different HRQoL instrument had been used. Finally, the follow-up period of the OLE was 24 weeks. Longer term data would be required to understand the impact of lurasidone on HRQoL beyond 24 weeks.

Conclusions

Treatment with lurasidone monotherapy provided a significant improvement across HRQoL items, with the greatest improvements in overall life satisfaction, social and family relationships, medication satisfaction, and ability to function in daily life. Improvement in Q-LES-Q-SF total and item scores were sustained for patients in the 6-month OLE study.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This post-hoc analysis was funded by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

C. Dembek, Y. Mao, K. Laubmeier, and M. Tocco are employees of Sunovion. Q. Fan and X. Niu were employees of Sunovion when the work was conducted. V.R. Anupindi is an employee of IQVIA, which received funding from Sunovion to conduct this analysis. A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they have received manuscript or speaker’s fees from Astellas, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Elsevier Japan, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Yakuhin, Lundbeck Japan, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Shire, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tsumura, Wiley Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and research grants from Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma and Shionogi. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the design of the post-hoc analysis, data analysis, interpretation of results, drafting of the manuscript, and providing final review.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank the participants of this study as well as the members of the Lurasidone Bipolar Disorder Study Group. We also thank Barbara Blaylock, PhD from Blaylock Health Economics LLC for providing medical writing support.

Data availability statement

This post-hoc analysis used confidential clinical trial data, which are not publicly available.

Previous presentations

An earlier version of this work was presented as a poster at the 2021 Neuroscience Education Institute Congress (Colorado Springs, CO; November 4–7, 2021) and the 2021 US Psych Congress (San Antonio, TX; October29–November 1, 2021).

References

- Carvalho AF, Firth J, Vieta E. Bipolar disorder. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(1):58–66.

- Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(3):241–251.

- Forte A, Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, et al. Long-term morbidity in bipolar-I, bipolar-II, and unipolar major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2015;178:71–78.

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137–150.

- Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) and international society for bipolar disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97–170.

- Miller S, Dell'Osso B, Ketter TA. The prevalence and burden of bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2014;169(Suppl 1):S3–S11.

- Morton E, Murray G, Michalak EE, et al. Quality of life in bipolar disorder: towards a dynamic understanding. Psychol Med. 2018;48(7):1111–1118.

- Intra-Cellular Therapies announces U.S. FDA approval of CAPLYTA® (lumateperone) for the treatment of bipolar depression in adults. New York: Globe Newswire; December 20; 2021. Available from: https://ir.intracellulartherapies.com/news-releases/news-release-details/intra-cellular-therapies-announces-us-fda-approval-caplytar.

- Rajagopalan K, Bacci ED, Ng-Mak D, et al. Effects on health-related quality of life in patients treated with lurasidone for bipolar depression: results from two placebo controlled bipolar depression trials. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:157.

- Calabrese JR, Durgam S, Satlin A, et al. Efficacy and safety of lumateperone for major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder: a phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial. AJP. 2021;178(12):1098–1106.

- Endicott J, Rajagopalan K, Minkwitz M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I and II depression: improvements in quality of life. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;22(1):29–37.

- Ketter TA, Sarma K, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone in the long-term treatment of patients with bipolar disorder: a 24-week open-label extension study. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(5):424–434.

- Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(2):160–168.

- Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, et al. Quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29(2):321–326.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York, NY: Routledge Academic; 1988.

- Endicott J, Paulsson B, Gustafsson U, et al. Quetiapine monotherapy in the treatment of depressive episodes of bipolar I and II disorder: improvements in quality of life and quality of sleep. J Affect Disord. 2008;111(2–3):306–319.

- Calabrese J, Rajagopalan K, Ng-Mak D, et al. Effect of lurasidone on meaningful change in health-related quality of life in patients with bipolar depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;31(3):147–154.

- Rush AJ, South C, Jain S, et al. Clinically significant changes in the 17- and 6-item Hamilton rating scales for depression: a STAR*D report. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:2333–2345.

- Niu X, Dembek C, Fan Q, et al. The impact of lurasidone on functioning and indirect costs in adults with bipolar depression: a post-hoc analysis. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):152–159.

- Léda-Rêgo G, Bezerra-Filho S, Miranda-Scippa Â. Functioning in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis using the functioning assessment short test. Bipolar Disord. 2020;22(6):569–581.