Abstract

Objective

Describe symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects among adults with ADHD in the US and assess their impact on quality of life (QoL) and work productivity.

Methods

An online survey among adults receiving ADHD medications in the US was conducted to collect information relating to symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects. Participants were recruited from the panel of a well-established market research firm, Dynata, from 26 July to 30 July 2021 and were included in the study if they met the eligibility criteria and were willing to participate in the survey. Correlations between symptoms and key outcomes (QoL/employment/work impairment) were estimated using linear regression analyses.

Results

Of 585 participants, 95.2% experienced ≥1 symptom associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects in the past month (average = 5.8 symptoms). The number of symptoms was significantly correlated with reduced QoL, reduced probability of being employed, and increased work/activity impairment. Among subgroups with insomnia/other sleep disturbances and emotional impulsivity/mood lability, 50.4% and 44.7% reported their symptoms had “a lot” or “extremely” negative impact on their overall well-being, respectively.

Conclusions

Symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects are common and have a substantial negative impact on QoL and reduces patients’ probability of employment. Improved management of ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects and more tolerable treatment options have the potential to improve QoL and work productivity among adults with ADHD.

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a persistent neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by symptoms of inattention and/or hyperactivity–impulsivity that impair functioning and is estimated to affect 4.4% of adults in the United States (US)Citation1–3. ADHD medications have demonstrated high effectiveness with medium-to-high effect sizes in meta-analyses (e.g. standardized mean difference of 0.7–1.2), especially for stimulantsCitation4,Citation5. Frontline treatment for most adults with ADHD typically consists of pharmacological intervention with stimulants, which have been shown to be effective in reducing ADHD core symptomsCitation6,Citation7; other treatment options include non-stimulants as well as psychotherapyCitation6,Citation8.

Pharmacological treatments for ADHD are associated with adverse side effectsCitation1,Citation9. In the longest-running clinical trial of methylphenidate in adult ADHD to dateCitation10, a higher proportion of patients receiving methylphenidate (N = 205) vs. placebo (N = 209) had sleep-related problems (e.g. insomnia [8.8 vs. 4.8%], restlessness [10.2 vs. 2.9%]), loss of appetite (22.4 vs. 3.8%), dry mouth (14.6 vs. 4.8%), weight loss (6.3 vs. 1.9%), and emotional dysregulation (e.g. irritability [6.8. vs 5.3%], depressed mood [19.0 vs. 12.9%]). Another clinical trial among children with ADHD has shown that clinically significant physiological adverse side effects, including insomnia, occurred more frequently among those who stayed on stimulant medication compared to those off medicationCitation11. In addition, many of these adverse side effects can be associated with the disease itself and it is challenging to distinguish whether they are related to the treatment or not. Regardless of the underlying cause, these ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects may have important consequences on patients’ well-beingCitation12,Citation13.

Prior studies on the potential impact of these ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects have been conducted among children and adolescents (e.g. impact on overall functional impairment, school grades, health service utilization)Citation11,Citation14–18, but their impact on the quality of life and work productivity of adult patients is less well characterizedCitation19. Importantly, it has been shown that ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects may affect patients’ persistence and adherence to treatmentCitation20, which are crucial determinants of treatment outcomes. Thus, additional information on the impact of ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects on the daily living of adults with ADHD is needed to better understand the burden and potential consequences associated with these adverse side effects, which may help improve the clinical management of this population. The current study aimed to describe symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects experienced by adults with ADHD receiving pharmacological treatment in the US through an online survey and assess their impact on participants’ quality of life and work productivity using validated scalesCitation21,Citation22 and self-reported ratings.

Methods

Study design and data source

An online survey was conducted from 26 July to 30 July 2021 to collect de-identified, individual-level data from treated adults with ADHD living in the US. Participants were recruited from the panel of Dynata, a well-established market research firm. An invitation containing the survey link was sent to all US panel members who indicated having ADHD. The survey questionnaire comprised four sections: (1) Screening and informed consent form, which included questions to confirm respondent eligibility and willingness to participate in the study; (2) Core section, which included questions on individual characteristics and general outcomes; (3) Sleep disturbances–specific section, which included questions specific to insomnia and other sleep disturbances (completed by individuals who reported having symptoms of insomnia and other sleep disturbances during the past month); and (4) Emotional impulsivity–specific section, which included questions specific to emotional impulsivity/mood lability (completed by individuals who reported having symptoms of emotional impulsivity/mood lability during the past month). Prior to data collection, pilot testing was conducted with three eligible participants in the form of semi-structured virtual interviews to review the survey content, ensure comprehension, and refine questions as needed. This study was approved under the exemption category by the Western Copernicus Group Institutional Review Board.

Study population

Adults residing in the US were eligible to participate in this study if they were diagnosed with ADHD and were receiving a pharmacological therapy treatment approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of ADHD symptoms at the time of the study. To capture a study population that could more closely reflect patients with ADHD treated in the real world, patients on multiple medications and those with treatment-resistant ADHD (e.g. chronic patients) were not excluded. Participants must have been somewhat comfortable reading and understanding English.

Study measures and outcomes

Information on participants’ demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics (e.g. current and prior treatments, frequency and reasons for skipping or missing a dose of current pharmacological treatment), experiences with symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects in the past month (defined as undesirable symptoms experienced by patients while on treatment, which could be associated with the ADHD disease state or the ADHD treatment received; adverse side effects were identified from the FDA labels of various ADHD medications), and the reasons for whether or not the symptom(s) was discussed with a healthcare provider was collected. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL), employment status, and work productivity and activity impairment characteristics were also assessed. Specifically, HRQoL was assessed using the Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Quality-of-Life (AAQoL) scale. The 29-item AAQoL scale includes four subscales—life productivity, psychological health, relationships, and life outlookCitation21. The total and subscale scores ranged from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating greater HRQoL. Participants’ work productivity and activity impairment characteristics were measured using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment – Specific Health Problem (WPAI-SHP)Citation22. WPAI-SHP outcomes are expressed as impairment percentages, with higher numbers indicating greater impairment and less productivity.

For participants who reported experiencing insomnia and other sleep disturbances or emotional impulsivity/mood lability in the past month, information on the characteristics of the respective symptoms (e.g. duration, frequency, treatment received for symptom management) and the participants’ self-reported impact on quality of life and work productivity (based on the options of “not at all,” “a little,” “somewhat,” “a lot,” and “extremely”) were collected.

Statistical analyses

Information collected was reported descriptively overall and among subgroups of participants who experienced selected symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects (i.e. insomnia and other sleep disturbances; emotional impulsivity/mood lability). Means, medians, and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables; frequency counts and percentages were reported for categorical variables.

Linear regression analyses with stepwise variable selection were conducted to estimate the correlation between symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects and key outcomes of interest after adjusting for participant characteristics (i.e. gender, age, and education level). Specifically, ordinary least square regression models were used to estimate continuous response variables (i.e. the AAQoL score or the WPAI-SHP activity impairment score), and a logistic regression model was used to estimate a binary response variable (i.e. employment).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 585 eligible adults with ADHD completed the survey and were included in the analyses. The mean age of the participants was 34 years; 58.5% of the participants were female; 74.4% were White, 14.2% were African American or Black, and 11.1% were Hispanic or Latino. The participants were from across all US regions (South: 43.9%, Midwest: 21.5%, West: 20.3%, Northeast: 14.2%), 29.1% had a graduate degree, and 63.2% were in a relationship. Based on information reported by the participants, 37.9% were first diagnosed with ADHD as adults, 65.6% had comorbid anxiety disorder, and 52.0% had comorbid depression ().

Table 1. Participant demographic and clinical characteristics.

ADHD treatment characteristics

As per the study eligibility criteria, all participants were receiving a pharmacological treatment at the time of data collection, with 93.7% receiving stimulants, 17.9% receiving non-stimulants, and 38.6% receiving combination therapy, including 11.6% who were receiving both stimulants and non-stimulants; 56.9% of participants were treated with their current ADHD medication for more than 24 months (). Most participants (73.2%) reported at least sometimes skipping or missing a planned dose of their current pharmacological treatment, with 19.7% reporting skipping or missing a planned dose at least half of the time. Of those skipping or missing a planned dose, the main reported reasons were problems with obtaining prescription (54.4%), forgot to take it (51.4%), timing of dosing conflicts with daily routine and/or other activities (25.0%), and experienced or to avoid potentially experiencing undesirable effects (19.9%).

Table 2. Treatment characteristics.

The majority of participants (81.2%) were also receiving non-pharmacological treatments for their ADHD (e.g. psychotherapy interventions, academic or cognitive skills training, organizational skills training). Furthermore, 87.2% of participants had previously received other ADHD medications, including stimulants (81.4%) and non-stimulants (20.3%), and 81.9% had previously received non-pharmacological treatments ().

Symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects

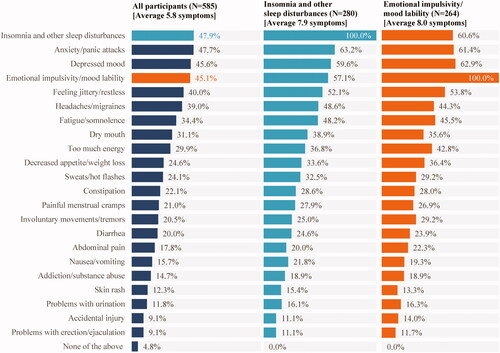

A vast majority (95.2%) of participants reported experiencing at least one symptom associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects in the past month, with an average of 5.8 symptoms per participant. Among the symptoms most frequently experienced by the participants were insomnia and other sleep disturbances (47.9%), anxiety/panic attacks (47.7%), depressed mood (45.6%), and emotional impulsivity/mood lability (45.1%). The subgroups of participants with insomnia and other sleep disturbances and with emotional impulsivity/mood lability had an average of 7.9 and 8.0 symptoms in the past month, respectively. More than half of participants in these subgroups also experienced anxiety/panic attacks, depressed mood, and feeling jittery/restless ().

Figure 1. Symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects experienced in the past month.

Among participants who experienced at least one symptom in the past month (N = 557), 35.7% did not discuss at least one symptom with their healthcare provider; this proportion was 17.5% among those with insomnia and other sleep disturbances and 19.3% among those with emotional impulsivity/mood lability. For participants who did not discuss at least one symptom with their healthcare provider, frequently reported reasons included symptoms were tolerable or not important enough to discuss (44.7%), choosing to manage the symptoms without the help of a healthcare provider (34.0%), thought it was more important to manage ADHD symptoms and/or other conditions (30.9%), planned to discuss the symptoms, but have not had time yet (28.7%), and did not want to take additional medications (25.5%).

HRQoL

Overall, the mean AAQoL score was 46.4 points among the participants, with a mean score ranging from 37.8 to 57.4 points in the four AAQoL domains (). Among subgroups, participants with insomnia and other sleep disturbances or emotional impulsivity/mood lability had numerically lower scores (42.9 and 42.6 points, respectively) than the overall sample in all AAQoL domains ().

Table 3. Impact of ADHD/treatment adverse side effects on HRQoL, employment, and work productivity and activity impairment.

The number of symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects was significantly correlated with a reduction in HRQoL. Specifically, each additional symptom experienced in the past month was associated with a decrease of 1.6 points in the total AAQoL score (p < .001; ). Of note, a reduction of ∼8 points is considered clinically important in adults with ADHDCitation23; this corresponds to ∼5 symptoms based on each symptom contributing to a 1.6-point decrease in the AAQoL score.

Employment

Overall, 67.4% of participants were employed and the average number of hours worked per week was 26.7 hours. Among subgroups, participants with insomnia and other sleep disturbances or emotional impulsivity/mood lability had a numerically lower rate of employment (60.0 and 60.2%, respectively) than the overall sample ().

The number of symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects was significantly correlated with a reduction in the probability of being employed. Specifically, each additional symptom experienced in the past month was associated with a 6% decrease in the likelihood of being employed (odds ratio: 0.94, p = .006; ).

Work productivity and activity impairment

Based on the WPAI-SHP scale, the average activity impairment due to health was 58.6% in the overall sample, and participants with insomnia and other sleep disturbances or emotional impulsivity/mood lability had a numerically higher rate of activity impairment (62.8 and 60.3%, respectively) ().

Among employed participants, average work impairment due to health was 60.7% (). Participants with insomnia and other sleep disturbances had a numerically higher rate of work impairment (62.5%) than the overall sample, but it was not the case for those with emotional impulsivity/mood lability (59.8%) ().

The number of symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects was significantly correlated with an increase in activity impairment due to ADHD. Specifically, each additional symptom experienced in the past month was associated with a 1.6-point increase in the percentage of activity impairment measured by the WPAI-SPH (p < .001; ).

Insomnia and other sleep disturbances—symptom characteristics and impact on quality of life and work productivity

Among the subgroup of participants who experienced insomnia and other sleep disturbances in the past month (N = 280), 47.9% had experienced the symptoms for more than 12 months (). The vast majority (91.4%) of participants experienced symptoms at least three times a week, including not being able to fall asleep within 30 min of going to bed (62.9%), difficulty falling asleep or sleeping through the night due to racing thoughts (54.6%), and waking up throughout the night and/or early morning (51.4%). Symptoms associated with insomnia and other sleep disturbances led to additional treatment, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological, in 80.7% of the participants, with 29.3% reported taking a prescribed medication at least three times a week ().

Table 4. Characteristics and management of insomnia and other sleep disturbances.

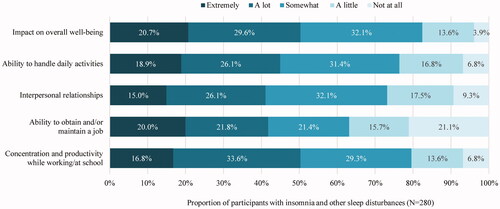

Over half (50.4%) of the participants in this subgroup reported that insomnia and other sleep disturbances had “a lot” or “extremely” negative impact on their overall well-being. Furthermore, the proportion of participants who reported insomnia and other sleep disturbances had “a lot” or “extremely” negative impact on their ability to handle daily activities, interpersonal relationships, ability to obtain and/or maintain a job, and concentration and productivity while working/at school activities ranged from 41.1 to 50.4% ().

Among employed participants who experienced insomnia or other sleep disturbances (N = 168), 44.6% reported missing at least one day of work in the past month due to these symptoms (). The mean number of workdays missed in the past month as a result of insomnia and other sleep disturbances was 2.5 days ().

Emotional impulsivity/mood lability—symptom characteristics and impact on quality of life and work productivity

Among the subgroup of participants who experienced emotional impulsivity/mood lability in the past month (N = 264), 43.2% had experienced the symptoms for more than 12 months (). The majority (80.3%) of participants experienced the symptoms often or very often, including feeling irritable and/or easily frustrated (67.8%), feeling overly emotional and/or agitated (63.6%), and having unpredictable mood and/or increased mood fluctuations (50.8%). Symptoms associated with emotional impulsivity/mood lability led to additional treatment, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological, in 84.1% of the participants, with 33.3% reported taking a prescribed medication at least three times a week ().

Table 5. Characteristics and management of emotional impulsivity/mood lability.

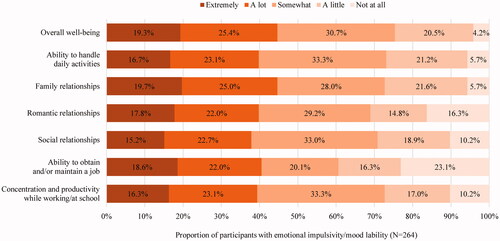

Almost half (44.7%) of the participants in this subgroup considered emotional impulsivity/mood lability as having “a lot” or “extremely” negative impact on their overall well-being. Furthermore, the proportion of participants who reported insomnia and other sleep disturbances had “a lot” or “extremely” negative impact on their ability to handle daily activities, interpersonal relationships, ability to obtain and/or maintain a job, and concentration and productivity while working/at school activities ranged from 37.9 to 44.7% ().

Among employed participants who experienced emotional impulsivity/mood lability (N = 159), 37.7% reported missing at least one day of work in the past month due to these symptoms (). The mean number of workdays missed in the past month as a result of emotional impulsivity/mood lability was 1.9 days ().

Discussion

The current online survey conducted among adults receiving ADHD medications in the US found that over 95% of the participants experienced at least one symptom associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects in the past month, and these symptoms imposed a substantial impact on the participants’ lives. Most participants in the subgroups who experienced insomnia and other sleep disturbances, or emotional impulsivity/mood lability symptoms perceived their symptoms as frequent, persistent, and had a lot or extremely negative impact on their quality of life and work productivity. Previous studies have shown that patients with ADHD experience multiple adverse side effects, some of which may be associated with treatmentsCitation1,Citation10. While existing studies have shown how ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects attributed to certain observed treatment outcomes (e.g. treatment changes, poor adherence) Citation24,Citation25, there is scant information on the impact of symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects on patients’ daily living. The current study quantified the effects of these symptoms and revealed their substantial impact that affected almost all adults with ADHD participating in this study. Specifically, each symptom was associated with a 1.6-point decrease in the overall AAQoL score, implying that the ∼8-point clinically important reduction in HRQoL would be reached in the presence of five or more symptomsCitation23, whereas the average number of symptoms experienced by the participants was 5.8 and was even higher among the subgroups. The number of symptoms was also found to be significantly correlated with a decreased likelihood of being employed and an increased rate of work and activity impairment. Notably, unemployment and productivity loss have previously been shown to constitute the largest proportion of total societal excess cost attributable to ADHD among adults in the US and accounted for US$96 billion in excess economic burdenCitation25. Considering that not all negative externalities can be translated into dollar amount, the actual burden imposed by these symptoms could be considerable. Meanwhile, it is reasonable to believe that not all symptoms have an equal impact on various outcomes. Although it may be challenging to delineate the effects of specific symptoms from the myriad of symptoms experienced by patients, this study showed that patients with insomnia and other sleep disturbances as well as those with emotional impulsivity/mood lability symptoms tended to have worse outcomes than the overall population, suggesting that the management of these symptoms may be crucial. Collectively, the findings of the current study demonstrate that symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects experienced by adults have a substantial impact on the quality of life and work productivity that could be of important clinical and economic consequences.

The frequency of symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects reported by participants of the current survey was substantially higher than the 40.3% found in a recent US chart review study among adult patients with ADHDCitation20. The apparent discrepancy is likely due to the assessment of these adverse side effects from the physician vs. patient perspective. It is important to note that the documentation of symptoms in medical charts depends largely on patients’ initiative to seek medical attention. However, the current survey found that almost a third of participants did not discuss at least one symptom with their healthcare provider for reasons such as decision to self-manage the symptoms, presumption that the healthcare provider could not help with the symptoms, and reluctance to take additional medications. The lack of discussion with physicians may explain the discrepancies between the physician and patient perspectives on patients’ experience during treatment and points to the considerable burden borne by patients in real life. The survey also found that patients tended to take additional medications (prescribed or over-the-counter) to manage the ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects. Polypharmacy not only increases costs and the complexity of the regimens, but also amplifies the risk of complicationsCitation26, all of which may lead to negative consequences in patient’s quality of life.

Relatively few studies have specifically assessed the impact of symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects on the quality of life and work productivity of adults with ADHD. In a post-hoc analysis among 206 adults with ADHD (medication status unknown), those with extreme deficient emotional self-regulation (DESR) symptoms (e.g. temper outbursts, emotional impulsivity) were found to have a lower quality of life, worse social adjustments, and were more likely to have never been married/divorced compared with those without extreme DESR symptomsCitation27. In a recent cross-sectional study that included 63 young adults with ADHD (71.4% receiving medication), emotional dysregulation was found to have a negative impact on HRQoL (measured by AAQoL) that was beyond that exerted by core ADHD symptomsCitation28. These studies illustrate that emotional symptoms can have a negative impact on the quality of life in adults with ADHD. The current study extends these findings by evaluating the impact of the most common symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects on the daily living of adults with ADHD and quantifying the burden exerted by these symptoms.

Considering that all symptoms in this study were captured over the month prior to data collection, the impact of symptoms described herein may represent only a tip of the iceberg in regard to the real burden experienced by patients over their ADHD journey, which often lasts for several years or even over the entire lifespan for some. Thus, it is imperative to address the unmet needs and alleviate patient burden by improving the current management of adult patients with ADHD. In this regard, enhanced physician–patient communication is crucial. There is a need for increased physician awareness to engage discussion with their patients regarding symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects and patient satisfaction during the entire treatment course. Patient education on how physicians can help manage these symptoms may also improve treatment experience and outcomes. This may be particularly important for adult ADHD patients, as they may have developed mechanisms over time to cope with these symptoms without seeking external help. Hence, it is important to foster patients’ trust in their physicians so that patients feel more comfortable discussing their problems, which will aid physicians in offering appropriate help. Additionally, even though some patients may not discuss certain symptoms with their physicians because they feel the symptoms are manageable, these adverse side effects are having a substantial impact on their quality of life, which may in turn affect their behavior (e.g. being less adherent) and hence treatment outcome. Thus, educating patients on the importance of discussing these symptoms with their physicians would be essential to maximize the potential benefit of treatment. Furthermore, designating more time for each appointment (which currently lasts for ∼15–20 min for primary care visits) to allow sufficient time for patients to raise all their concerns and questions and for physicians to assess all potential symptoms is warranted; this may require system changes in payment structure and healthcare resource allocationCitation29,Citation30. Collaborative care approach involving interdisciplinary healthcare teams may also be implemented to help improve outcomes of patients with ADHDCitation31.

Notably, it was observed in the current study that up to 1 in 5 participants displayed reduced adherence to their ADHD treatments due to symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects. Thus, more tolerable ADHD treatments with fewer side effects may help improve treatment adherence for this subset of patients. In fact, it has previously been shown that ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects were important drivers of treatment changes in adults with ADHD, and that suboptimal improvement of symptoms and undesirable side effects were the among the most common reasons for a lack of satisfaction with current treatment optionsCitation20. Additionally, the number of treatment changes has also been associated with increased healthcare costsCitation32 Therefore, more effective and tolerable treatment options coupled with better management of ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects may result in increased patient satisfaction and potentially greater adherence and persistence, which may in turn improve quality of life and word productivity and alleviate the clinical and economic burden of adult ADHD.

Limitations

The findings of the current study should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. Respondents of the survey were those accessible through Dynata’s panel and who wished to participate in the study; accordingly, the sample may not be representative of the US population of treated adults with ADHD. A large proportion of participants had comorbid anxiety disorder and depression; hence, the findings may not be generalizable to milder or unselected ADHD cases with different comorbidity profiles. Additionally, data analyzed for this study relied on participants’ recollection of past events. Although the survey was designed to ask about events that occurred in the recent past as much as possible, recall bias or errors in the accuracy or completeness of respondents’ recalled experiences may have occurred. Furthermore, given it would be difficult for the participants to distinguish treatment-related adverse side effects from other symptoms experienced, this survey collected information on all symptoms experienced that could be associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects. Thus, the rate of treatment-related adverse side effects experienced in real-world settings could not be accurately captured.

Conclusions

Findings from this study suggest that symptoms associated with ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects are common among adults treated for ADHD in the US, and these symptoms were significantly correlated with reduced HRQoL, reduced probability of being employed, and increased activity impairment. Furthermore, the subsets of participants with insomnia and other sleep disturbances and emotional impulsivity/mood lability perceived the symptoms as having a substantial negative impact on their quality of life and work productivity. Thus, better management of ADHD/treatment-related adverse side effects and more tolerable treatment options have the potential to improve quality of life and work productivity among adults with ADHD.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Financial support for this research was provided by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. The study sponsor was involved in several aspects of the research, including the study design, the interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

JS is an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. AC received research support from Allergan, Takeda/Shire, Emalex, Akili, Ironshore, Arbor, Aevi Genomic Medicine, Neos Therapeutics, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, KemPharm, Supernus, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration; was on the advisory board of Takeda/Shire, Akili, Arbor, Cingulate, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Adlon, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, Supernus, and Corium; received consulting fees from Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, KemPharm, Supernus, Corium, Jazz, Tulex Pharma, and Lumos Pharma; received speaker fees from Takeda/Shire, Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Pfizer, Tris, and Supernus; and received writing support from Takeda/Shire, Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Pfizer, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, and Tris. MC, MGL, RB, and AG are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

MC, MGL, RB, and AG contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. JS and AC contributed to study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the applicable ethical regulations and was exempt from full review by the Western Copernicus Group Institutional Review Board, as the survey did not collect any participant-identifying information. Participant consent was collected at the time of participation.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Flora Chik, PhD, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study are subject to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act privacy restrictions and are not publicly available. De-identified data could be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Faraone SV, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15020.

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716–723.

- Asherson P, Buitelaar J, Faraone SV, et al. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: key conceptual issues. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(6):568–578.

- Stuhec M, Lukic P, Locatelli I. Efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of lisdexamfetamine, mixed amphetamine salts, methylphenidate, and modafinil in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(2):121–133.

- Roskell NS, Setyawan J, Zimovetz EA, et al. Systematic evidence synthesis of treatments for ADHD in children and adolescents: indirect treatment comparisons of lisdexamfetamine with methylphenidate and atomoxetine. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(8):1673–1685.

- Adler LA, Farahbakhshian S, Romero B, et al. Healthcare provider perspectives on diagnosing and treating adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Postgrad Med. 2019;131(7):461–472.

- Cortese S, Adamo N, Del Giovane C, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(9):727–738.

- Faraone SV, Silverstein MJ, Antshel K, et al. The adult ADHD quality measures initiative. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(10):1063–1078.

- Posner J, Polanczyk GV, Sonuga-Barke E. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2020;395(10222):450–462.

- Kis B, Lucke C, Abdel-Hamid M, et al. Safety profile of methylphenidate under long-term treatment in adult ADHD patients – results of the COMPAS study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2020;53(6):263–271.

- Charach A, Ickowicz A, Schachar R. Stimulant treatment over five years: adherence, effectiveness, and adverse effects. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(5):559–567.

- Brod M, Schmitt E, Goodwin M, et al. ADHD burden of illness in older adults: a life course perspective. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(5):795–799.

- van Andel E, Ten Have M, Bijlenga D, et al. Combined impact of ADHD and insomnia symptoms on quality of life, productivity, and health care use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2020;29:1–12.

- Klassen AF, Miller A, Fine S. Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents who have a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):e541-7–e547.

- Langberg JM, Dvorsky MR, Becker SP, et al. The impact of daytime sleepiness on the school performance of college students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a prospective longitudinal study. J Sleep Res. 2014;23(3):318–325.

- Storebo OJ, Pedersen N, Ramstad E, et al. Methylphenidate for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents - assessment of adverse events in non-randomised studies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD012069.

- Wehmeier PM, Schacht A, Barkley RA. Social and emotional impairment in children and adolescents with ADHD and the impact on quality of life. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(3):209–217.

- Anastopoulos AD, Smith TF, Garrett ME, et al. Self-regulation of emotion, functional impairment, and comorbidity among children with AD/HD. J Atten Disord. 2011;15(7):583–592.

- Wajszilber D, Santiseban JA, Gruber R. Sleep disorders in patients with ADHD: impact and management challenges. Nat Sci Sleep. 2018;10:453–480.

- Schein J, Childress A, Cloutier M, et al. Reasons for treatment changes in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a chart review study. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):377.

- Brod M, Johnston J, Able S, et al. Validation of the adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder quality-of-life scale (AAQoL): a disease-specific quality-of-life measure. Qual Life Res. 2006;15(1):117–129.

- Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–365.

- Tanaka Y, Brod M, Lane JR, et al. What is a clinically relevant improvement in quality of life in adults with ADHD? J Atten Disord. 2019;23(1):65–75.

- Gajria K, Lu M, Sikirica V, et al. Adherence, persistence, and medication discontinuation in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder - a systematic literature review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:1543–1569.

- Schein J, Adler LA, Childress A, et al. Economic burden of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults in the United States: a societal perspective. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28(2):168–179.

- Muth C, Blom JW, Smith SM, et al. Evidence supporting the best clinical management of patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy: a systematic guideline review and expert consensus. J Intern Med. 2019;285(3):272–288.

- Surman CB, Biederman J, Spencer T, et al. Understanding deficient emotional self-regulation in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a controlled study. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2013;5(3):273–281.

- Ben-Dor Cohen M, Eldar E, Maeir A, et al. Emotional dysregulation and health related quality of life in young adults with ADHD: a cross sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):270

- French B, Sayal K, Daley D. Barriers and facilitators to understanding of ADHD in primary care: a mixed-method systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28(8):1037–1064.

- Linzer M, Bitton A, Tu SP, Association of Chiefs and Leaders in General Internal Medicine (ACLGIM) Writing Group*, et al. The end of the 15-20 minute primary care visit. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1584–1586.

- Stuhec M, Tement V. Positive evidence for clinical pharmacist interventions during interdisciplinary rounding at a psychiatric hospital. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13641.

- Schein J, Childress A, Adams J, et al. Treatment patterns among adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the United States: a retrospective claims study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(11):2007–2014.