Abstract

In recent years, US payers have increased usage of formulary exclusions as a means to help manage costs. Earlier this year, one of the largest pharmacy benefit managers in the country added Eliquis (apixaban), the most widely used anticoagulant, to its list of excluded medicines from its formulary, raising concerns by physicians and patients. In this commentary, we examine the potential impacts of formulary exclusion of a drug like apixaban—a treatment for patients with atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism to help prevent stroke and clotting events and which has been demonstrated to have a strong efficacy and safety profile. We discuss the effect of formulary exclusions on patients’ ability to access the most clinically appropriate treatment for their health needs, along with possible effects on their health and well-being. We also report descriptive results on apixaban-treated patients with traditional Medicare coverage who faced a formulary exclusion of apixaban in 2017, and these patients’ observed behaviors. We found that the majority of these patients remained on apixaban either through pre-emptively switching to a different Part D drug plan with apixaban coverage or applying for formulary exception. Our findings suggest that formulary exclusion did not help to achieve the goal of switching patients to less costly medications but created additional hurdles for patients to access their preferred treatment and increased patient burden. Alternative ways to manage payer costs may be needed to help avoid poor outcomes and reduce the burden placed on patients in their efforts to access life-saving medications.

Introduction

In response to rising costs accompanying advances in therapeutic options, payers across the United States (US) have expanded use of utilization management measures and formulary restrictions.Citation1 One of the more extreme measures adopted by payers has been formulary exclusions, in which payers drop coverage of specified drugs from their formulary, requiring patients to apply for an exception to maintain coverage for the excluded drug.Citation2 In recent years, use of formulary exclusions has accelerated. From 2014 to 2020, the number of medications removed from standard formularies of at least one of the three largest US pharmacy benefit managers (PBM) increased by 676%, from 109 to 846.Citation2 Across therapeutic areas, cardiovascular medications were the fourth largest category of excluded medications, accounting for 9.4%.Citation2

Eliquis (apixaban) is one of four FDA-approved non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) used to prevent stroke/systemic embolism (stroke/SE) and blood clots in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) without moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis or a mechanical heart valve (hereafter referred to as AF) and in patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE), respectively.Citation3 Despite being the most widely used NOAC and a class I recommended treatment for AF by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society,Citation4,Citation5 apixaban has been removed from multiple drug formularies. In 2017, multiple large Medicare Part D plans in the US introduced formulary restrictions, including formulary exclusion, that reduced patient access to apixaban. In 2022, one of the largest PBMs in the US with nearly 110 million members removed apixaban from its 2022 Preferred Drug List in favor of warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist, and rivaroxaban, another NOAC (other NOACs, dabigatran and edoxaban were not listed on its national preferred formulary to begin with).Citation6,Citation7 Only after significant pushback from multiple physician organizations and patient groups was apixaban reinstated on its national preferred formulary after a six-month absence.Citation8,Citation9 While formulary exclusions are intended to manage payer costs, these actions, as this example demonstrates, have sparked concern across patients and physicians over the potential consequences of creating such barriers to accessing optimal treatment.

Clinical concerns with apixaban formulary exclusions

A growing body of evidence has revealed differences in effectiveness and safety among different anticoagulants. For instance, apixaban has been found to have lower risk of stroke/SE as well as major bleeding—a potential complication inherent to anticoagulation—compared to warfarin in both randomized clinical trials and US-based real-world data (RWD) studies.Citation10–13 While no head-to-head clinical trial compares apixaban and other NOACs such as rivaroxaban, a number of US-based RWD studies have shown apixaban to be associated with a lower risk of stroke/SE and major bleeding compared to rivaroxaban in AF patients.Citation14,Citation15 Furthermore, apixaban has been found to be associated with a significantly lower risk of stroke/SE and major bleeding compared to warfarin and rivaroxaban in various high risk subgroups of AF patients such as those with diabetes, with multimorbidity, with polypharmacy, with prior bleeding events, or those who are frail, obese or aged 80 or older.Citation16–24 Studies also suggest that a twice-daily dosing regimen of NOACs (such as with apixaban or dabigatran) offers a more balanced risk-benefit profile with respect to stroke prevention and intracranial hemorrhage, compared to a once-daily dosing regimen (such as with rivaroxaban or edoxaban).Citation25 In addition to stroke/SE prevention in AF, real-world studies have shown apixaban to have equivalent or improved efficacy in prevention of recurrent VTE compared to rivaroxaban.Citation26,Citation27 Given the supporting evidence from clinical trials and real-world studies, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend apixaban (category 1) above rivaroxaban (category 2A) for the treatment of VTE in patients with cancer who do not have gastric or gastroesophageal lesions.Citation28–30

The access barriers that formulary exclusions create have raised concerns around physicians’ ability to prescribe the most clinically appropriate treatment for their patients. The American Society of Hematology posited that restricting commercial health plan formularies to rivaroxaban and warfarin allows medical decisions to be made by insurance companies as opposed to physicians, a stance echoed by 15 other cardiovascular non-profits in response to a large PBM’s formulary exclusion of apixaban.Citation31–33 Furthermore, applying for formulary exception to maintain coverage approval requires additional administrative efforts that can delay or inhibit critical treatment.Citation2,Citation32 A 2020 commercial claims analysis showed that claim rejections due to formulary restrictions led to a week-long delay in receiving antiepileptic treatment among patients with focal seizure compared to patients with an initially approved claim (p < .0001).Citation34 Even more alarmingly, a 2010 commercial claims analysis on smoking cessation (SC) treatment showed that only 15.3% of patients filled an SC treatment prescription in the six months after facing a rejected claim for varenicline, the newest SC treatment at the time of publication, due to lack of coverage.Citation35 Additionally, formulary exclusions could lead to an increase in workload for healthcare professionals, which may affect quality of care and potentially delay the discharge of admitted patients in hospital settings.

Potential impacts on patients

Although formulary exclusions generally aim to encourage patient switching to the PBM’s preferred “on-formulary” therapies, patients may respond in different ways. For conditions like AF and VTE where the consequences can be life-threatening and treatments can have meaningful differences, patients may elect to switch to a different health plan, if possible, to maintain coverage of their preferred therapy or petition their health plan for formulary exception. Patients who choose to switch to their PBM’s preferred “on-formulary” therapy (“non-medical switching”) may face less administrative hassle and lower out-of-pocket costs; however, such switching can be accompanied by increased risk of worse health outcomes. For instance, switching from apixaban to rivaroxaban may lead to increased risk of bleeding.Citation36 This risk can be particularly pronounced among older patientsCitation33 and may inadvertently increase overall patient healthcare costs.Citation36 For patients with fragile support systems to assist in their care, formulary exclusions that disrupt their treatment may even prompt discontinuation of anticoagulant treatment altogether. Such treatment discontinuations can have serious consequences, increasing the risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and death.Citation37,Citation38

Beyond the clinical impacts previously mentioned, the psychological toll on patients from formulary exclusions can be substantial.Citation7,Citation39 Patients may experience extreme stress and anxiety from the uncertainty of formulary exception approval and the difficulties of navigating an administrative process, which is often characterized by a lack of information and support. Patients who contemplate switching to a new health plan face the complexity of researching options and weighing multiple considerations, which can be non-trivial particularly for patients on multiple medications. For patients who non-medically switch to a different treatment, stress and anxiety can arise from being on a potentially suboptimal treatment with the ever-present possibility of severe consequences arising. Beth Waldron has written about her experiences as a patient facing formulary exclusion of apixaban by her PBM. While patients like her could apply for formulary exception, approval would require first failing on rivaroxaban, an event marked by a blood clot or bleeding—potentially fatal occurrences. Moreover, if approved, coverage would be at a higher formulary tier for her, requiring an additional $2400 per year. She has elected to switch to rivaroxaban, a decision that has reignited feelings of anxiety and depression around both the possible recurrence of a life-threatening clotting event from VTE and the higher risk of bleeding, an event from which her father died.Citation7

Highlighting an additional dimension of pressure faced by patients, Steven Newmark, director of policy and general counsel at the Global Healthy Living Foundation, has reported that many patients learn of their plan’s formulary exclusion when they try to pick up their medication at the pharmacy. This can place them in a difficult predicament, having to decide whether to absorb much higher out-of-pocket costs for a drug on which they have been stable or to stop treatment and potentially switch to a new therapy—a decision that can have major clinical consequences—without their physician present.Citation39

Assessing patient response to formulary exclusion of apixaban—a retrospective claims analysis

To better understand how patients respond to formulary exclusion of apixaban, we conducted a retrospective claims analysis among AF patients with traditional Medicare coverage who were treated with apixaban and faced an upcoming formulary exclusion of apixaban by their Part D plan. In particular, our analyses focused on patients who were treated with apixaban through the end of 2016 and faced an upcoming formulary exclusion of apixaban in 2017 by their Part D plan. This time period was selected due to the number of Part D plans, including those from large insurers, who elected to enact formulary exclusion of apixaban in 2017. Nationwide administrative claims data for Medicare beneficiaries with Parts A, B, and D (100% sample) were used from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Our analyses assessed the following: (1) the proportion of patients who pre-emptively switched to a different Part D plan and characteristics of their new plan, (2) the proportion of patients who elected to remain on their same Part D plan, and (3) treatment patterns in 2017 among the two previously mentioned groups of patients, including apixaban continuation, switching to another anticoagulant, and discontinuation without switching to another NOAC or warfarin.

To be included in the study sample, patients were required to meet a pre-specified set of eligibility criteria. These included being initiated on apixaban at any point between 2013 and 2016 and having continuous apixaban treatment from initiation through 31 December 2016, defined as no supply gaps greater than 30 days. Patients were also required to have at least one diagnosis code for AF and no codes for hip or knee replacement surgery, transient AF, valvular heart disease, VTE, or mechanical valve replacement. (The analyses focused on patients with AF due to its higher prevalence than VTE—the lifetime risk of AF is 1 in 4 for adults 40 years of age and over, while the risk of VTE is 1 in 12 for middle-aged adults.Citation40,Citation41) Additionally, patients had to have continuous enrollment in Medicare Parts A, B, and D for the entirety of 2016 (baseline period) and 2017 (follow-up period) or until death if occurring in 2017. (Patients were not assessed beyond 2017, since Part D plans could implement formulary changes for the 2018 benefit year, which could impact patients’ treatment patterns and health plan switching for this benefit year.) Importantly, patients were also required to be enrolled in a Part D plan in 2016 that implemented a formulary exclusion of apixaban for the 2017 benefit year. Patients were excluded from the study sample if any of the following criteria were met—enrolled in a Part D plan in 2016 that underwent termination, consolidation, or service area changes (“renewals”) in 2017, which could have forced patients to switch Part D plans for 2017 or created uncertainties in their coverage; had been treated with another oral anticoagulant prior to apixaban; received special subsidies.

Patients were regarded as having pre-emptively switched to a different Part D plan if they elected to switch from their 2016 Part D plan to a different drug plan for the 2017 benefit year during their open enrollment period. (In other words, these patients could have remained on the same Part D plan for both 2016 and 2017 [and been subject to their plan’s formulary exclusion of apixaban] but instead elected to switch to a different plan for 2017.)

For the treatment pattern outcomes, the following definitions were applied. Treatment discontinuation was defined as a supply gap extending longer than 30 days. The discontinuation date was defined as the date of the last claim in the patient’s continuous treatment episode plus its corresponding days of supply. Switching was defined as a prescription for another oral anticoagulant within 90 days before or after the previous treatment’s discontinuation date.

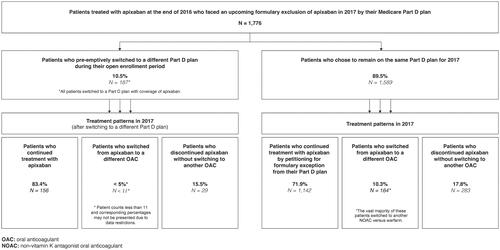

Results of our analysis are summarized in with baseline characteristics summarized in . Among the 1776 patients who met the eligibility criteria, 187 (10.5%) pre-emptively switched to a different Part D plan. Among these patients, all switched to a Part D plan that had apixaban on formulary. The vast majority (83.4%) of these patients continued on apixaban, while almost none switched to another anticoagulant, and the remaining patients (15.5%) discontinued anticoagulant treatment altogether.

Figure 1. Summary of plan switching and treatment patterns among patients who faced formulary exclusion of apixaban by their Medicare Part D plan.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients treated with apixaban at the end of 2016 who faced an upcoming formulary exclusion of apixaban by their Medicare Part D plan.

Among the 1589 patients (89.5%) who chose to remain on the same Part D plan, the majority continued on apixaban (71.9%) despite the additional activities required for applying for formulary exception. Only 10.3% of patients switched to another anticoagulant (9.8% switched to another NOAC, while very few switched to warfarin). The remaining 17.8% of patients discontinued anticoagulants altogether.

These findings suggest strong patient reluctance to switch to other therapies when confronted with formulary exclusion of apixaban. While the exact drivers of this are unclear, the willingness of patients to undergo the additional hurdles of applying for exception or even switching Part D plans to remain on apixaban may reflect unease with switching therapies for non-medical reasons. The high rates of patients exhibiting these behaviors also speak to the additional burden placed on patients from these restrictions. These burdens may disproportionally affect vulnerable subgroups, such as older patients or socioeconomically disadvantaged patients who may lack the support and resources to readily contend with the administrative efforts required. To the extent that this could precipitate treatment delays, gaps, or discontinuation, this could expose these patients to increased risk of acute events like stroke/SE and hospitalization.

Moreover, if a goal of formulary exclusion of apixaban was to have patients switch to less costly, formulary-covered medications, our findings suggest that the goal may have been missed. The high proportions of patients applying for and being granted exceptions instead of switching therapies may have inadvertently increased administrative costs for payers. These costs can be considerable. A previous study found that the administrative cost of drug prior authorization, a utilization management restriction that also requires extensive processing, was estimated to be approximately $6.0 billion annually (2019 USD) for payers before even considering implementation costs.Citation1

It should be noted that our analyses are subject to some limitations. For instance, the administrative claims database used in our analysis does not capture activities required by the Part D plans for obtaining a formulary exception or the length of time it took for patients to receive formulary exception approval. As such, we were unable to perform more detailed assessments of patients’ transaction journeys, hurdles to formulary exception, and potentials delays in treatment access. Additionally, the data do not capture reasons for patients’ treatment discontinuation or switches to another NOAC or warfarin. Consequently, we cannot directly ascertain whether patients’ treatment switches were for non-medical reasons. That said, we suspect that such treatment switches among the study’s patients who experienced formulary exclusion were driven by imposition of these restrictions, because all of these treatment switches were to oral anticoagulants that were on-formulary for the patients’ Part D plans. Finally, our analyses did not assess safety and efficacy outcomes as these were beyond the scope of our analyses; assessment of these outcomes could represent an area for future research.

Conclusion

Formulary exclusions not only undermine physicians’ ability to prescribe the most clinically appropriate treatment for a given patient, they can also cause patient distress over treatment and health plan decisions. In the case of apixaban, formulary exclusion did not help to achieve the goal of switching patients to less costly medications, as the majority of patients facing formulary exclusion under their Medicare Part D plans chose to apply for formulary exception to remain on apixaban or switch to another plan with apixaban coverage. As revealed in our analyses, the application of formulary exclusion merely created additional hurdles for patients to access their preferred treatment, increasing patient burden. Alternative ways to manage payer costs may need to be explored to help avoid poor outcomes and reduce the burden placed on patients in their efforts to access life-saving medications.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Steven Deitelzweig (SD) has received consulting fees from BMS/Pfizer in connection with the development of this manuscript. Emi Terasawa (ET) and Ahmed Noman (AN) are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., which has received consulting fees from BMS/Pfizer in connection with the development of this manuscript. Amiee Kang (AK) and Nipun Atreja (NA) are employees of BMS and hold stock/options. Dionne M. Hines (DMH) and Xuemei Luo (XL) are employees of Pfizer and hold stock/options. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed to study concept and design, data analysis, or interpretation of the data. Emi Terasawa has drafted the manuscript; all authors have provided critical revisions. Ahmed Noman has provided statistical analysis support.

Acknowledgements

None.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Howell S, Yin PT, Robinson JC. Quantifying the economic burden of drug utilization management on payers, manufacturers, physicians, and patients: study examines the economic burden of drug utilization management on payers, manufacturers, physicians, and patients. Health Aff. 2021;40(8):1206–1214.

- Xcenda . Skyrocketing growth in PBM formulary exclusions raises concerns about patient access. AmerisourceBergen Xcenda; 2020. Available from: https://www.xcenda.com/insights/skyrocketing-growth-in-pbm-formulary-exclusions-raises-concerns-about-patient-access

- Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Eliquis (apixaban) [package insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. [revised 2021 January; cited 2022 May 20]. Available from: www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/202155s034lbl.pdf.

- Heidenreich PA, Estes NAM, Fonarow GC, et al. 2020 Update to the 2016 ACC/AHA clinical performance and quality measures for adults with atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(3):326–341.

- Diagnostic and Interventional Cardiology. New atrial fibrillation guidelines recommend NOACs over warfarin. Wainscot Media; 2019. Available from: https://www.dicardiology.com/article/new-atrial-fibrillation-guidelines-recommend-noacs-over-warfarin#:∼:text=January%2030%2C%202019%20%E2%80%94%20Updated%20atrial,reducing%20the%20risk%20of2520stroke

- Dawwas GK, Cuker A, Connors JM, et al. Apixaban has superior effectiveness and safety compared to rivaroxaban in patients with commercial healthcare coverage: a population‐based analysis in response to CVS 2022 formulary changes. Am J Hematol. 2022;97(5):E173–E176.

- Waldron B. Nonmedical switching of anticoagulants: the patient impact when formulary exclusions limit drug choice. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022;6(2):e12675.

- Becker Z. CVS re-adds BMS, Pfizer’s Eliquis to formulary after tough negotiations, patient pushback. Fierce Pharma. 2022. Available from: https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/eliquis-will-return-cvs-formulary-after-wave-criticism-cites-lower-net-cost-negotiations-bms

- Tepper N. CVS Caremark returns Eliquis to formulary after outcry. Modern Healthcare; 2022. Available from: https://www.modernhealthcare.com/patient-care/cvs-caremark-returns-eliquis-formulary-after-outcry#:∼:text=CVS%20Health%20will%20return%20blood, company%20notified%20providers%20last%20week

- Lip GYH, Keshishian A, Li X, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants among nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients. Stroke. 2018;49(12):2933–2944.

- Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):981–992.

- Yao X, Abraham NS, Sangaralingham LR, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(6):e003725.

- Graham DJ, Baro E, Zhang R, et al. Comparative stroke, bleeding, and mortality risks in older Medicare patients treated with oral anticoagulants for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Am J Med. 2019;132(5):596–604.e11.

- Ray WA, Chung CP, Stein CM, et al. Association of rivaroxaban vs apixaban with major ischemic or hemorrhagic events in patients with atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2021;326(23):2395–2404.

- Fralick M, Colacci M, Schneeweiss S, et al. Effectiveness and safety of apixaban compared with rivaroxaban for patients with atrial fibrillation in routine practice. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(7):463.

- Lip GYH, Keshishian AV, Kang AL, et al. Oral anticoagulants for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in frail elderly patients: insights from the ARISTOPHANES study. J Intern Med. 2021;289(1):42–52.

- Deitelzweig S, Keshishian A, Li X, et al. Comparisons between oral anticoagulants among older nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(8):1662–1671.

- Lip GYH, Keshishian AV, Kang AL, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(5):929–943.

- Deitelzweig S, Keshishian A, Kang A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants among NVAF patients with obesity: insights from the ARISTOPHANES study. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):1633–1657.

- Lip GYH, Keshishian A, Kang A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants among non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients with polypharmacy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2021;7(5):405–414.

- Deitelzweig S, Keshishian A, Kang A, et al. Use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and multimorbidity. Adv Ther. 2021;38(6):3166–3184.

- Lip GYH, Keshishian AV, Zhang Y, et al. Oral anticoagulants for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in patients with high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8):e2120064.

- Deitelzweig S, Keshishian AV, Zhang Y, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants among nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients with active cancer. JACC CardioOncol. 2021;3(3):411–424.

- Lip GYH, Keshishian A, Kang A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants in non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients with prior bleeding events: a retrospective analysis of administrative claims databases. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2022;54(1):33–46.

- Clemens A, Noack H, Brueckmann M, et al. Twice- or once-daily dosing of novel oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention: a fixed-effects meta-analysis with predefined heterogeneity quality criteria. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99276.

- Aryal MR, Gosain R, Donato A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of apixaban compared to rivaroxaban in acute VTE in the real world. Blood Adv. 2019;3(15):2381–2387.

- Dawwas GK, Leonard CE, Lewis JD, et al. Risk for recurrent venous thromboembolism and bleeding with apixaban compared with rivaroxaban: an analysis of real-world data. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(1):20–28.

- Streiff MB, Abutalib SA, Farge D, et al. Update on guidelines for the management of cancer-associated thrombosis. Oncologist. 2021;26(1):e24–e40.

- Carrier M, Abou-Nassar K, Mallick R, et al. Apixaban to prevent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(8):711–719.

- Khorana AA, Soff GA, Kakkar AK, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in high-risk ambulatory patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(8):720–728.

- Letter from the Partnership to Advance Cardiovascular Health to Troyen Brennan, Chief Medical Officer of CVS Health. 2021 [cited 2022 May 1]. Available from: https://www.stoptheclot.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/CVSSwitchLetterFinal.pdf

- American College of Cardiology. ACC, ASH meet with CVS Caremark on new DOAC formulary change. 2022. Available from: https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2022/01/13/14/15/acc-ash-meet-with-cvs-caremark-on-new-doac-formulary-change

- Letter from the American Society of Hematology to CVS Health. 2021 [cited 2022 May 1]. Available from: https://www.hematology.org/-/media/hematology/files/advocacy/testimony-and-correspondence/2021/ash-letter-to-cvs.pdf.

- Mehta D, Davis M, Epstein AJ, et al. Impact of formulary restrictions on antiepileptic drug dispensation outcomes. Neurol Ther. 2020;9(2):505–519.

- Zeng F, Chen C-I, Mastey V, et al. Utilization management for smoking cessation pharmacotherapy: varenicline rejected claims analysis. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(9):667–674.

- Dhamane AD, Baker CL, Rajpura J, et al. Continuation with apixaban treatment is associated with lower risk for hospitalization and medical costs among elderly patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(10):1769–1776.

- Rivera-Caravaca, JM, Roldán V, Asunción Esteve-Pastor M, et al. Cessation of oral anticoagulation is an important risk factor for stroke and mortality in atrial fibrillation patients. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117(7):1448–1454.

- Carnicelli AP, Al-Khatib SM, Xavier D, et al. Premature permanent discontinuation of apixaban or warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart. 2021;107(9):713–720.

- Formulary exclusions, non-medical switching jeopardize disease control, patient trust. Healio Rheumatology. 2020. Available from: https://www.healio.com/news/rheumatology/20201214/formulary-exclusions-nonmedical-switching-jeopardize-disease-control-patient-trust

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, et al. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;110(9):1042–1046.

- Bell EJ, Lutsey PL, Basu S, et al. Lifetime risk of venous thromboembolism in two cohort studies. Am J Med. 2016;129(3):339 e19–339 e26.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of chronic diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1992;45(6):613–619.

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Medical care. 2005;43(11):1130–1139.