?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objectives

This observational retrospective real-world study examined changes in healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) pre- and post-initiation of aripiprazole once-monthly (AOM 400) in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder.

Methods

Electronic health record-derived, de-identified data from the NeuroBlu Database (2013–2020) were used to identify patients ≥18 years with schizophrenia (n = 222) or bipolar I disorder (n = 129) who were prescribed AOM 400, and had visit data within 3, 6, 9, or 12 months pre- and post-initial AOM 400 prescription. Rates of inpatient hospitalization, emergency department visits, inpatient readmissions, and average length of stay were examined and compared over 3, 6, 9, and 12 months pre-/post-AOM 400 using a McNemar test.

Results

Statistically significant differences were seen in both schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder patient cohorts pre- and post-AOM 400 in inpatient hospitalization rates (p < .001 all time points, both cohorts) and 30-day readmission per patient rates (p < .001 all time points, both cohorts). Statistically significant improvement in mean length of stay was observed in both cohorts at all time points, except for at six months in patients with schizophrenia. Emergency department visit rates were significantly lower after AOM 400 initiation for both cohorts at all time points (p < .001).

Conclusions

A reduction in the rate of hospitalizations, emergency department visits, 30-day readmissions, and average length-of-stay was observed for patients diagnosed with either schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder, which suggests a positive effect of AOM 400 treatment on HCRU outcomes and is supportive of earlier analyses from different data sources.

Introduction

Schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder are complex, chronic, and recurrent mental disorders. Schizophrenia affects 0.25–0.64% of the United States (US) populationCitation1. It is characterized as a heterogeneous and severe mental illness with debilitating long-term outcomes and is associated with severe cognitive and functional impairmentCitation2. Bipolar I disorder affects approximately 1.5% of the US populationCitation3. Bipolar I disorder is characterized by fluctuating periods of mania and potentially depression/hypomaniaCitation2,Citation4.

Both schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder have a high burden of illness from a healthcare perspective, largely impacting socioeconomics, interpersonal relationships, education, and workplace productivityCitation5,Citation6. Schizophrenia is responsible for more than $150 billion in annual healthcare costs in the USCitation6 and bipolar I disorder is responsible for an estimated $219.1 billion in US annual healthcare costsCitation7. Instigated by a growing fiscal pressure to reduce reliance on hospital treatment and shorten hospital stays, medication adherence has become a focus of increasing concern in the management of these psychiatric disordersCitation8.

A major challenge in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder is found in treatment non-adherence, with a mean rate of treatment non-adherence being approximately 40-60% in patients with schizophreniaCitation9–11 and 22–66% in patients with bipolar I disorderCitation12. Poor adherence is a particular challenge in schizophrenia due to the illness’s association with social isolation, stigma, and comorbid substance misuseCitation13. The nature of schizophrenia, other comorbid conditions such as depression, lack of insight (attitudes and beliefs about the nature of one’s own illness), and cognitive dysfunction also contribute to treatment non-adherenceCitation13,Citation14. Apart from undermining the usefulness of treatment and leading to poor outcomes, non-adherence also increases the risk of symptom exacerbation, relapse, re-hospitalization, and suicideCitation4,Citation15–18. Non-adherence to medication in schizophrenia can result in an increased relapse risk of up to five times that of adherent patients; and non-adherence in individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder leads to greater utilization of healthcare services and increased mental health expendituresCitation19–21.

To address the challenge of patient adherence, innovations in treatment regimens for psychiatric illnesses include long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of second-generation atypical antipsychotics, designed to have a sustained release over several weeks/months. LAI formulations have been shown to significantly reduce patient burden for treatment adherence compared to oral formulations and may allow stable, consistent dosing and improved outcomesCitation2. Aripiprazole once-monthly (AOM 400) (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Princeton, NJ, USA and H. Lundbeck A/S, Deerfield, IL, USA) is an LAI formulation of aripiprazole monohydrate that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of schizophrenia in 2013Citation22, and maintenance monotherapy of bipolar I disorder in 2017Citation23.

While clinical trials of AOM 400 have demonstrated reduced re-hospitalizationsCitation24,Citation25, the results may not translate to the real world, where patient profiles are heterogenous, clinical workflows vary, and quantitative outcome measures are not consistently captured. This observational retrospective real-world study aimed to examine changes in healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) pre- and post-AOM 400 initiation using real-world data (RWD).

Methods

Data source

This study leveraged electronic health record (EHR)-derived, de-identified data from the NeuroBlu Database (NeuroDB) (Holmusk Technologies Inc., New York, NY, USA) Version 20R1, a longitudinal behavioral health real-world database comprising both structured and semi-structured patient-level clinical dataCitation26. At the time of this study, NeuroDB included data from 25 behavioral health centers across the US spanning over 20 years, consisting of data from over 560,000 patients, treated by over 11,000 clinicians. This study followed the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected Data (RECORD) checklist.

Study design, duration, and inclusion

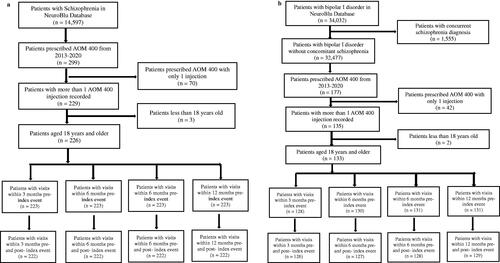

This study assessed the impacts of AOM 400 on HCRU by comparing psychiatric-specific resource use before and after the initiation of AOM 400. The schizophrenia cohort started at three months with 222 patients () and stayed consisted at each of the subsequent timepoints. The bipolar I disorder cohort started at 3 months with 126 patients () and gained 1 patient at each of the subsequent timepoints (at 6 months n = 127, at 9 months n = 128, and at 12 months n = 129).

Figure 1. (a) Cohort attrition chart for treatment effects of HCRU (schizophrenia cohort). (b) Cohort attrition chart for treatment effects of HCRU (bipolar I disorder cohort).

We first conducted descriptive analysis to characterize the cohorts, followed by a mirror-type comparison HCRU outcomes up to 12 months before and after AOM 400 initiation. Change in HCRU was assessed by examining the frequency of psychiatric-specific inpatient hospitalizations, emergency department visits, average length of stay, and 30-day readmission rates pre- and post-index date. Separate analyses were conducted for each disease cohort.

Assessment of resource utilization pre-/post-index event

To measure patient healthcare resource utilization, we examined four different measures: inpatient hospitalization rate, emergency department visit rate, 30-day readmission event rate and 30-day per patient readmission rate. These measures pertained only to psychiatric visits as the NeuroDB contained only behavioral health sites. Inpatient hospitalization rate was defined as the proportion of inpatient visits against all patients in the cohort within a period, defined by the equation:

Where t refers to time (month)

Emergency department visit rate was defined as the proportion of emergency department visits against all patients in the cohort within a period, defined by the equation:

Where t refers to time (month)

The 30-day psychiatric readmission event rate was defined as the proportion of patients with at least two inpatient hospitalizations within the span of 30 days against all patients in the cohort with inpatient admission within a period, defined by the equation:

Where t refers to the period examined (month)

The 30-day psychiatric readmission rate per patient was defined as the proportion of 30-day inpatient readmissions from a patient’s inpatient admission within a time period, defined by the equation:

Where t refers to the period examined (month) and i refers to the patient.

Length of stay and 30-day per patient readmission rate were the only HCRU outcomes that were calculated at a per patient level. The calculated rates of all other HCRU metrics were reported per 1000 patients. Average length of stay was determined as the mean number of days during inpatient hospitalization during a defined period.

Outcome measures and statistical analysis

Rates of HCRU up to 3, 6, 9, and 12 months before and after AOM 400 prescription, and pre- and post-30-day readmission event rates were compared in a mirror-type analysis using a McNemar test; and a paired t-test was used to compare pre- and post-30-day readmission rates per patient. Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons to correct for Type I errors.

Results

HCRU

Patients with schizophrenia had a mean age of 36.6 (SD:12.6) and patients with bipolar I disorder had a mean age of 37.5 (SD: 12.7) (). Of the patients with schizophrenia, 62.2% were male, whereas patients with bipolar I disorder consisted of marginally more women (56.6%). Both schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder cohorts were predominantly white (68.0%, 76.6%, respectively).

Table 1. Baseline cohort characteristics.

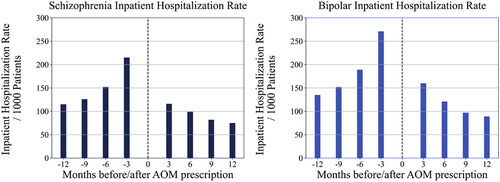

Statistically significant differences were found between pre- and post-inpatient hospitalization rates in patients with schizophrenia and patients with bipolar I disorder. An improvement of 99 inpatient hospitalizations per 1000 patients with schizophrenia (p < .001) and 111 inpatient hospitalizations per 1000 patients with bipolar I disorder (p < .001) were observed when comparing three months pre-AOM 400 prescription to three months post-AOM 400 prescription. For patients with schizophrenia, significant improvements were also seen at 6 months (53 hospitalizations/1000; p < .001), 9 months (44 hospitalizations/1000; p < .001), and 12 months (40 hospitalizations/1000; p < .001) post-AOM 400 initiation. Similarly, improvements were noted for patients with bipolar I disorder as well (68 hospitalizations/1000 at 6 months, 55 hospitalizations/1000 at 9 months, 46 hospitalizations/1000 at 12 months; p < .001 for all comparisons) ().

Figure 2. Inpatient hospitalization rate/1000 patients in schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder cohorts.

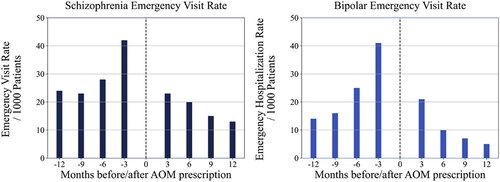

Emergency department visit rates in patients with schizophrenia and patients with bipolar I disorder were also significantly lower at all months of comparison pre- and post-AOM 400 prescription (). An improvement of 19 emergency department visits/1000 patients with schizophrenia and 20 visits/1000 patients with bipolar I disorder were observed when comparing three months pre- to three months post-AOM 400 prescription (p < .001). At 6 and 9 months, an improvement of 8 visits/1000 was noted and at 12 months an improvement of 11 visits/1000 was noted for patients with schizophrenia (p < .001 for all comparisons). For patients with bipolar I disorder, an improvement of 15 visits/1000 was noted at 6 months, and 9 visits/1000 at 9 and 12 months post-AOM 400 initiation (p < .001 for all comparisons).

Figure 3. Pre/post emergency department visit rates in schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder cohorts.

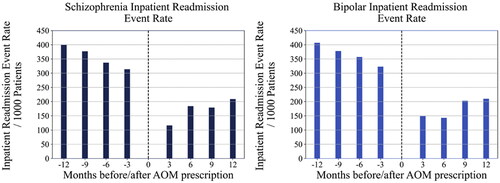

For inpatient 30-day readmission event rates by cohort, both the schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder cohorts were significantly different at all months of comparison pre- and post-AOM 400 prescription (). An improvement of 198 fewer inpatient readmission events per 1000 patients (p < .001) with schizophrenia; and 174 fewer inpatient readmission events per 1000 patients (p < .001) with bipolar I disorder were observed when comparing three months pre- to three months post-AOM 400 prescription. Readmission rates at 6, 9, and 12 months were also statistically significantly lower for patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder (p < .001 for all comparisons). Similarly, 30-day inpatient readmission per patient rates for both patient cohorts were significantly different at all months of comparison pre- and post-AOM prescription (data not shown).

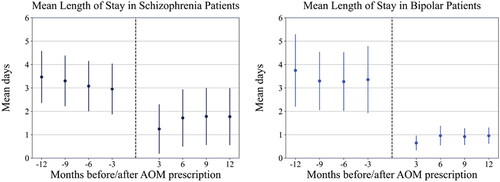

Statistically significant improvement in mean length of stay was noted for patients with schizophrenia at 3 months (mean change = 1.8 days; p = .021), 9 months (mean change = 1.5 days; p = .031), and 12 months (mean change = 1.7 days; p = .017) post-AOM 400 initiation, but not at 6 months (mean change = 1.4 days; p = .051). For patients with bipolar I disorder, significant improvements in mean length of stay were noted at all time points post-AOM prescription (mean change = 2.8 days at 3 months, 2.3 days at 6 months, 2.4 days at 9 months, and 2.8 days at 12 months; p < .001 for all comparisons) ().

Discussion

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are widely accepted as the gold standard in medical research. However, their validity can be undermined by the exclusion of patients who do not meet eligibility criteria and as such may not be representative of wider clinical practice. Additionally, patients recruited in RCTs may be less severely ill, and their medication use are likely to be closely monitoredCitation27. This gap between research and real-world clinical care creates a disparity between what is expected to happen versus what really happens. Improvements in HCRU requires evidence rooted in the reality of clinical practice, before, during, and after intervention. Therefore, real-world studies may be better suited to assess LAI use in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorderCitation28. Several real-world studies that have examined the effectiveness of LAIs on HCRU and recurrent hospitalizations in patients with schizophrenia found that HCRU was lower and readmission rates were reduced when patients were prescribed LAIs in comparison to oral medicationsCitation16,Citation29,Citation30.

This study examined the impact of AOM 400 on HCRU in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder, using data from electronic health records from behavioral health practices. Statistically significant improvements were noted between pre- and post- AOM 400 initiation for patients with schizophrenia and patients with bipolar I disorder in rates of inpatient hospitalization, emergency department visits, inpatient readmissions, and mean duration of stay. Our findings are congruent with both clinical trial data and previous real-world claims data analysis, which have all noted effectiveness of AOM 400 regarding psychiatric hospitalization. Prior clinical studies of AOM 400 have showed significant reduction in inpatient length of stay and total inpatient encounters post-AOM 400 initiation in both patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorderCitation23–25.

Real-world claims data analyses also support the effectiveness of AOM 400 in improvement in adherence and hospitalization risk. A US claims-based study in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder showed that adjusted mean adherence was higher in patients with AOM 400 compared to oral antipsychotics; and that patients in the oral antipsychotic cohort had a higher risk of discontinuation in both schizophrenia and bipolar I disorderCitation31. Another study in the real-world setting conducted in Japan, found that AOM 400 was associated with longer treatment persistence than oral treatments, suggesting that the use of AOM 400 may contribute to consistent antipsychotic treatmentCitation32.

Two separate US claims data analyses also underscored the impact of AOM 400 on hospitalizations. These studies compared AOM 400 to other LAI formulations and found that risks of hospitalization were statistically significantly higher with haloperidol and risperidone than with AOM 400 in both schizophreniaCitation33 or bipolar I disorderCitation33,Citation34.

Limitations

These findings should be reviewed in light of several limitations. The data used in this study were collected at varied intervals across disorders, clinicians, inter-clinic practices, and settings; therefore, missing, lost, or unusable data is to be expected. Second, the pre- and post-analyses were cumulative; rates of 12-month analyses include data from 3, 6, and 9 months. Due to this cumulative approach, rates from Month 9 to Month 12 may not reflect that they may be lower. Further, data closer to the index date may reflect higher severity in the pre-AOM 400 periods. A Bonferroni adjustment was applied to account for the overlap; however, an alternative approach would be to calculate separate quarterly rates from Months 0–3, 4–6, 7–9, and 10–12. A caveat of this approach may be that when assessing patients who have data at 9–12 months both pre- and post-treatment, patient numbers may be quite limited, thereby lowering statistical power. In addition, patients in the latter time groups (e.g. 4–6 months) would logically have patients from 0 to 3 months as well, thereby not fully mitigating the issue. Lastly, NeuroDB contains prescription records of AOM 400, but not whether the patient has filled their prescription or returned to the clinic for an injection. Since NeuroDB does not contain claims for filled prescriptions, AOM 400 use was estimated based on clinic visits at monthly intervals post-prescription as a proxy for actual injection dates. However, use of visit data rather than actual prescription claims may mean that actual treatment duration was shorter than estimated.

Conclusions

Data from real-world behavioral health EHRs included patients that would likely be excluded from RCTs, allowing us to bridge the gap between research and real-world clinical practice. Following AOM 400 prescription, we found a reduction in the rate of inpatient hospitalizations, emergency department visits, 30-day readmissions, and average length of stay, indicating that AOM 400 may have positive effect on HCRU outcomes within 12 months of treatment initiation for patients with schizophrenia and patients with bipolar I disorder. These findings are supportive of earlier analyses from different data sourcesCitation31–34 and support further studies which may be necessary in understanding the true impact of AOM 400 initiation for patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder on HRCU outcomes.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. and Lundbeck LLC.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

HCW and XH are employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. MT and HF were employees of Lundbeck LLC. at the time of the study. RP has received funding from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR301690), the Medical Research Council (MR/S003118/1), the Academy of Medical Sciences (SGL015/1020), Holmusk, and Janssen. SW, MN, ST, SS, MR, RP, and JS report current or past employment of KKT Technology Pte. Ltd or its subsidiaries (Holmusk Technologies Inc. or Holmusk Europe Limited). Holmusk Technologies Inc. was paid for this research. A. John Rush has received consulting fees from Compass Inc., Curbstone Consultant LLC, Emmes Corp., Evecxia Therapeutics, Inc., Holmusk Technologies, Inc., ICON, PLC, Johnson and Johnson (Janssen), Liva-Nova, MindStreet, Inc., Neurocrine Biosciences Inc., Otsuka-US; speaking fees from Liva-Nova, Johnson and Johnson (Janssen); and royalties from Wolters Kluwer Health, Guilford Press and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX (for the Inventory of Depressive Symptoms and its derivatives). He is also named co-inventor on two patents: U.S. Patent No. 7,795,033: Methods to Predict the Outcome of Treatment with Antidepressant Medication, Inventors: McMahon FJ, Laje G, Manji H, Rush AJ, Paddock S, Wilson AS; and U.S. Patent No. 7,906,283: Methods to Identify Patients at Risk of Developing Adverse Events During Treatment with Antidepressant Medication, Inventors: McMahon FJ, Laje G, Manji H, Rush AJ, Paddock S. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Previous presentation

A poster containing this information was previously presented at the American Society for Clinical Psychopharmacology 2022 annual meeting (Scottsdale AZ, 31 May–3 June 2022).

Acknowledgements

None.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- National Institutes of Mental Health. Schizophrenia. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health; 2022. Available from: NIMH » Schizophrenia (nih.gov.)

- American Psychiatric Society. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Available from: https://cdn.websiteeditor.net/30f11123991548a0af708722d458e476/files/uploaded/DSM%2520V.pdf

- Blanco C, Compton WM, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 bipolar I disorder: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions-III. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;84:310–317.

- Saklad SR, Kreys TJ, Phan SV. Aripiprazole long-acting (ABILIFY MAINTENA) for treatment of schizophrenia. Ment Health Clin. 2015;5(4):149–161.

- Vieta E, Berk M, Schulze TG, et al. Bipolar disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18008.

- Mahabaleshwarkar R, Lin D, Joshi K, et al. Characteristics and healthcare burden of patients with schizophrenia treated in a US integrated healthcare system. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2021;24(2):47–59.

- Bessonova L, Ogden K, Doane MJ, et al. The economic burden of bipolar disorder in the United States: a systematic literature review. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:481–497.

- Donovan JM, Steinberg SM, Sabin JE. Managed mental health care: an academic seminar. Am Psychother Theory Res Pract Train. 1994;31(1):201–207.

- Cramer JA, Rosenheck R. Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(2):196–201.

- Patel MX, Taylor M, David AS. Antipsychotic long-acting injections: mind the gap. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(S52):S1–S4.

- Goff DC, Hill M, Freudenreich O. Strategies for improving treatment adherence in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;7(Suppl 2):20–26.

- Lingam R, Scott J. Treatment non-adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105(3):164–172.

- Haddad PM, Brain C, Scott J. Nonadherence with antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: challenges and management strategies. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2014;5:43–62.

- Lachaine J, Lapierre ME, Abdalla N, et al. Impact of switching to long-acting injectable antipsychotics on health services use in the treatment of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(3 Suppl 2):S40–S47.

- Kim HO, Seo GH, Lee BC. Real-world effectiveness of long-acting injections for reducing recurrent hospitalizations in patients with schizophrenia. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2020;19:1.

- Berk L, Hallam KT, Colom F, et al. Enhancing medication adherence in patients with bipolar disorder. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(1):1–16.

- Colom F, Vieta E, Tacchi MJ, et al. Identifying and improving non-adherence in bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(s5):24–31.

- Leucht S, Heres S. Epidemiology, clinical consequences, and psychosocial treatment of nonadherence in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 5):3–8.

- Gianfrancesco FD, Sajatovic M, Rajagopalan K, et al. Antipsychotic treatment adherence and associated mental health care use among individuals with bipolar disorder. Clin Ther. 2008;30(7):1358–1374.

- Rascati KL, Richards KM, Ott CA, et al. Adherence, persistence of use, and costs associated with second-generation antipsychotics for bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(9):1032–1040.

- Johnson FR, Ozdemir S, Manjunath R, et al. Factors that affect adherence to bipolar disorder treatments: a stated-preference approach. Med Care. 2007;45(6):545–552.

- Aripiprazole once-monthly in patients with schizophrenia. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01959035. Rockville (MD): US Food and Drug Administration. [updated 2017 Mar 17; accessed 2022 Jun 2]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01959035

- Calabrese JR, Jin N, Johnson B, et al. Aripiprazole once-monthly as maintenance treatment for bipolar I disorder: a 52-week, multicenter, open-label study. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):14.

- Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, et al. Effect of long-acting injectable antipsychotics vs usual care on time to first hospitalization in early-phase schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(12):1217–1224.

- Kane JM, Sanchez R, Zhao J, et al. Hospitalization rates in patients switched from oral anti-psychotics to aripiprazole once-monthly for the management of schizophrenia. J Med Con. 2013;16(7):917–925.

- Patel R, Wee SN, Ramaswamy R, et al. NeuroBlu, an electronic health record (EHR) trusted research environment (TRE) to support mental healthcare analytics with real-world data. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e057227.

- Suzuki T. A further consideration on long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a narrative review and critical appraisal. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2016;13(2):253–264.

- Kirson NY, Weiden PJ, Yermakov S, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of depot versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: synthesizing results across different research designs. J Clin Psych. 2013;19;74(6):6018.

- Lafeuille MH, Dean J, Carter V, et al. Systemic review of long-acting injectables versus oral atypical antipsychotics on hospitalization in schizophrenia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(8):1643–1655.

- Tiihonen J, Haukka J, Taylor M, et al. A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(6):603–609.

- Yan T, Greene M, Chang E, et al. Medication adherence and discontinuation of aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg (AOM 400) versus oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder: a real-world study using US claims data. Adv Ther. 2018;35(10):1612–1625.

- Iwata N, Inagaki A, Sano H, et al. Treatment persistence between long-acting injectable versus orally administered aripiprazole among patients with schizophrenia in a real-world clinical setting in Japan. Adv Ther. 2020;37(7):3324–3336.

- Yan T, Greene M, Chang E, et al. All-cause hospitalization and associated costs in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder initiating long-acting injectable antipsychotics. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(1):41–47.

- Yan T, Greene M, Chang E, et al. Impact of initiating long-acting injectable antipsychotics on hospitalization in patients with bipolar I disorder. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7(11):1083–1093.