Abstract

Objective

Low rates of inclusion of real-world evidence (RWE) during regulation may arise from lack of clarity and consensus on its definition. A conceptually mature definition of RWE may have pragmatic utility, increasing its inclusion during regulation. The aim was to develop a definition of RWE to promote inclusion in regulatory submissions and assess its conceptual maturity.

Methods

Thirteen medical affairs pharmaceutical physicians completed two qualitative online surveys to generate items needed in a definition of RWE. Items that reached a consensus index of > 50% (CI > = 0.51) were retained in the final definition. The maturity of the definition was assessed using concept analysis.

Results

After attrition, 11 participants completed the study and generated 18 items to be included in a definition of RWE. All items reached the consensus threshold and were included. The definition was conceptually mature on three of the four dimensions: the potential for a consensual definition across stakeholders, a description of its characteristics and clear preconditions and outcomes. Further research is needed to delineate the boundaries of RWE.

Conclusions

A definition of RWE was generated that may increase its inclusion during medicines regulation, especially with further refinement from regulators and other stakeholders.

Introduction

Since the legislation of the twenty first Century Cures Act in 2016 in the USCitation1, the use of real-world evidence (RWE) during drug development has been given increasing importance worldwide. It is widely accepted as the basis for evidence-based medicine and provides evidence on cost-effectiveness and quality of life (QoL) for payors. Additionally, the importance of RWE to patients has been highlighted as social media has been utilized as a dissemination channel and forum for debate among patient-experts and researchers with lived experience of disease and health conditionsCitation2. Such debate has highlighted the need for patient-centricity in clinical research, especially in terms of whether findings harm or benefit patients, the intended beneficiaries. Due to their ability to collect data on groups that are routinely excluded from RCTs, RWE studies have been recognized as a useful supplement during clinical development, although well documented limitations, such as their high number of confounders, have largely restricted accepted use of RWE to post-approval stages.

RWE studies have been used for some specific pre-approval purposes, such as control group comparison for efficacy and tolerability studies and patient identificationCitation3, but debate over what RWE should be and do in the context of regulatory approval remainsCitation4. Recent estimates suggest that only 40% of marketing authorization applications made to the European Medicines Agency in 2018–2019 included RWECitation5, with this figure decreasing to just 13% for applications relating to orphan drugs for rare diseasesCitation6, which are among conditions in which RWE may be most useful due to high unmet needCitation7. This is despite the fact that the inclusion of RWE at the regulatory stage may increase the breadth of the population indicated for a medicineCitation6, reduce the time to maximal medicine adoption by up to 22% and increase the depth of maximal medicine adoption by 31%Citation8. A lack of clarity and standardization regarding whether and how RWE can be used for regulatory purposes has been suggested as a reason for low rates of inclusion in regulatory submissionsCitation9.

Additionally, there is a current lack of consensus between and within stakeholder groups regarding the definition of RWE ()Citation10–13,Citation16–18, even though RWE generated for the purposes of medicine adoption must satisfy the decision-making needs of multiple stakeholdersCitation14. There is a need for consensual definitions to understand the impact of established clinical and research practices on patients and to facilitate researchers’ ability to replicate and interpret findingsCitation15. Definitions determine outcome measures used in research and influence the validity of resultsCitation19. Development of guidelines and quality standards for the use of RWE at the regulatory stage are currently at the research stageCitation9. Therefore, the development of a clear, consensual definition of RWE could have material consequences for its potential use during medicines regulation. Definitions that aid the implementation of a construct in practice have been described as conceptually mature by the fulfilment of four criteria: a clear definition, clear characteristics, fully described preconditions and outcomes, and delineated boundariesCitation20. Assessment of conceptual maturity can determine the pragmatic utility of a definition towards improved implementationCitation21,Citation22.

Table 1. Regulatory policy, frameworks and definitions of RWD/RWE.

The aim of this study was to observe a consensus of expert opinion on the definition of RWE among medical affairs pharmaceutical physicians (MAPPs), whose main areas of work include the generation and submission of RWE to stakeholders in the pharmaceutical industryCitation14,Citation23, and assess its conceptual maturity to promote regulatory use.

Methods

Study design and conceptual basis

Neutral theory is a conceptual framework that characterizes the accuracy of a construct as a function of relevant versus irrelevant indicators included in an observationCitation24. The Neutral, or exhaustive, list for a construct includes all relevant indicators and excludes all irrelevant indicators. Accordingly, a Neutral list including only relevant definition items should provide an accurate characterization of RWE. The Jandhyala method is a means for operationalizing Neutral theory.

The Jandhyala method is a novel approach for observing proportional group awareness and consensus that is distinct from other consensus methods, such as Delphi and modified Delphi approaches, as it contains metrics at the awareness and consensus stages to quantify participants’ awareness of, and agreement with, each list item generatedCitation25,Citation26. It has been used previously to generate definitionsCitation27 and to develop and validate core datasets as well as QoL and disease-severity scalesCitation28–30 and is conducted in two online survey rounds, Awareness Round (1) and Consensus Round (2). Conceptual maturity was assessed using concept analysis in reference to existing regulatory definitions. Criteria for assessment of conceptual maturity were adapted to the study context from Morse et al.Citation20 to include a criterion of “a consensual definition” rather than “a clear definition”.

Sample size

Sample size was determined by data saturation, the point at which no new information is obtained, and was in line with other qualitative studies showing that the collection of further data above this point failed to add anything meaningful to resultsCitation31. Of all types of saturation used in qualitative researchCitation32, data saturation was selected as an appropriate way to ensure data quality and adequate sample size, as this was in line with the methodological approach of Grounded TheoryCitation33 regarding the aim of the research question to generate a definition of RWE using an inductive process. Previous, conceptually similar applications of the Jandhyala method suggested that a sample size of nine to 12 is necessary to achieve data saturation, broadly in line with adequate sample size for other consensus methodsCitation34 and sufficient to generate enough data given that the unit of analysis is definition items, and each participant was required to contribute at least three.

Participants and recruitment

In total, 13 MAPPs were recruited using convenience sampling via professional networks to participate in the MAPP evidence generating program, which comprised several research projects on the professional role of MAPPs in the pharmaceutical industry over a 12-month period from December 2020 to December 2021. This study was conducted between October 2021 and November 2021. To be included, MAPPs had to have at least 2 years of medical affairs experience at the regional or global level at a pharmaceutical company with offices in the UK. There was no limitation regarding where MAPPs were based. Although 10 were in the UK at the time of the study, MAPPs were responsible for medical affairs globally and across regional territories covering specific countries, including Germany, Switzerland, Ireland, the Nordics, the US and the UK. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the study commenced. Responses were anonymized, and consensus round list items were not identifiable. In accordance with international regulations, favorable ethical opinion for this study was granted by the King’s College London Research Ethics Committee (Reference number: MRA-21/22-26399).

Development of a definition for real-world evidence

MAPPs completed the two-stage anonymous qualitative online Jandhyala method, comprising Consensus Round (1) and Awareness Round (2). For Awareness Round (1), participants were asked “What components do you feel should be included in the definition of Real-world Evidence?” In free-text responses, they provided at least three and up to 50 items they believed should be included. Responses were coded by two research analysts, with discrepancies settled by the author. The awareness index of each item was calculated by dividing the frequency at which an item was suggested by the frequency of the most commonly occurring item. We combined items generated by participants according to standard grammatical rules and presented the synthesized definition to participants in Consensus Round (2):

Real-World Evidence is scientific knowledge that answers a research question relevant to regulators, payors, prescribers, and patients and is supported by the results of an observational cohort clinical study, which has used local disease management practices for investigations and treatments and employed primary or secondary data collection from an unselected and representative disease population outside an RCT.

Results

Development of a definition for real-world evidence

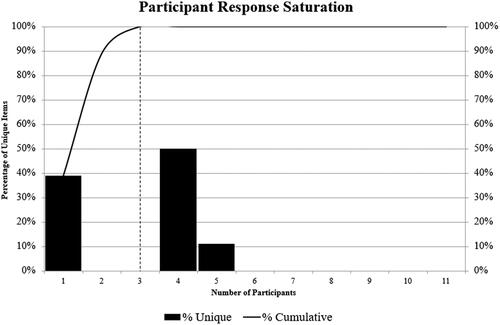

In total, two MAPPs dropped out, so 11 were included in the final analysis. Participants generated 18 unique items in Awareness Round (1) (). Participants 1, 4, and 5 provided unique items in Awareness Round (1) (), showing that saturation on elements suggested for inclusion in the definition was observed at three MAPPs only. Item awareness indexes ranged from 0.11 (Item 12, “effectiveness”) to 1.00 (Item 11, “secondary data source”). All but two items had a consensus index of 1.00. Item 4 (“an observational cohort clinical study”) and Item 8 (“patients”) had a consensus index of 2.00. All items met the threshold for inclusion in the final definition. Of these, four (12, 13, 14, 15) referred to endpoints and were placed in the expanded definition (shown in brackets) to give the following:

Figure 1. Data saturation. Bars represent the percentage of unique items generated by participants in order of entry into the study; line represents the cumulative percentage of unique items, which was achieved by three participants in total.

Table 2. Definition items generated by participants.

Real-World Evidence is scientific knowledge that answers a research question relevant to regulators, payors, prescribers, and patients and is supported by the results of an observational cohort clinical study, which has used local disease management practices for investigations and treatments and employed primary or secondary data collection from an unselected and representative disease population outside an RCT [including stakeholder-specific endpoints, such as effectiveness, safety, quality of life and healthcare utilization].

Awareness scores for half the items were high; however, consensus scores for all items were low, showing that participants agreed or strongly agreed with their inclusion in the definition ().

Conceptual maturity of the definition

Concept analysis of the definition showed that it was conceptually mature on three of the four criteria adapted from Morse et al.Citation20 (). The definition delineated some but not all boundaries of RWE, partially fulfilling the fourth criterion. Analysis of the generated definition in the context of existing definitions showed that it varied from existing definitions in terms of its conceptual maturity across all criteria except the fourth, which was largely similar across all definitions.

Table 3. Conceptual maturity of the generated definition of real-world evidence.

Discussion

Current low rates of inclusion of RWE in regulatory submissions have been attributed to a lack of clarity about whether and how it can be used appropriately for various purposesCitation9, and current definitions provide little guidance as to this. The aim of this study was to observe a comprehensive consensus definition of RWE that may increase the inclusion of RWE in regulatory submissions and the generation and use of high-quality RWE during drug development. Participants agreed on a definition of RWE comprising 18 unique items via the Jandhyala method that fulfils three of the four criteria for conceptual maturity adapted from Morse et al.: a consensual definition, a clear description of its characteristics, and a description of its preconditions and outcomes. The definition delineated some but not all boundaries of RWE and varied conceptually from existing definitions, promoting the inclusion of RWE at the regulatory stage.

Consensual definition

With regards to the development of a definition with utility across stakeholders, existing regulatory guidelines are either in the strategic phaseCitation13,Citation18 with broad frameworksCitation9,Citation17 or have proposed guidelines that have yet to be fully described and agreed between stakeholdersCitation11–13. However, development of a definition that can be used by all stakeholders in medicine adoption (regulators, payors, prescribers and patients) may promote greater understanding and improved implementation of RWE. Given that all stakeholders have unique and varied RWE needsCitation14, a consensual definition may provide a unifying framework against which these varying needs can be better understood and navigated by pharmaceutical companies. While there is a risk of overgeneralization and subsequent omission of context-specific elements needed for practical utility, the expanded definition generated here provides for both general and stakeholder-specific applications.

Description of the characteristics of RWE

Findings here were saturated at three MAPPs, which indicates the quality of the research question and the suitability of MAPP expertise for providing comprehensive data on the topic. Existing definitions characterized RWE as (clinical) evidence derived from an analysis of RWD, whereas the generated definition described the characteristics of RWE as comprising scientific knowledge that answers a research question supported by the results of an observational cohort clinical study. Defining RWE as evidence derived from analyses of RWD is beneficial in that there are few limits placed on what evidence can be classified as RWE; however, use criteria that are too wide may impair decision-making regarding implementation in practiceCitation35. Movement towards a definition that clearly describes the characteristics of a construct may aid implementationCitation22, which can be understood in terms of the regulatory use of RWE. Regulatory RWE must meet strict quality criteria to be fit for purpose; however, clear quality guidelines for regulatory grade RWE are still being developed, meaning that optimal strategies for RWE implementation during medicines regulation are lacking. Additionally, appropriate use cases have not been clarified, although case studies demonstrate successful inclusion at the regulatory stage and findings report related benefitsCitation36,Citation37.

Categorizing RWE as knowledge based on the results of an observational cohort clinical study may aid decision-making regarding quality standards, guidelines for use and appropriate use cases, as it provides a unit of information that has existing meaning and utility within the regulatory context. Quality standards, guidelines for use and appropriate use cases are already defined for observational cohort clinical studies and can be more easily applied and adapted where necessary for a regulatory context than attempting to define the applicability of analyses of RWD on a case-by-case basis. Thus, the generated definition promotes the inclusion of RWE at the regulatory stage by providing a heuristic for decision-making that can be applied to a variety of use cases throughout the regulatory context.

Preconditions

The main pre-condition for all existing definitions was that RWE is based on RWD, which all regulators defined except for the Therapeutic Goods Administration. Perhaps more importantly, the generated definition and two of the existing definitionsCitation17,Citation18 referred to the need for RWE to be based on routinely collected data; however, the generated definition specified that the research must have used local disease management practices for investigations and treatments. This caveat is essential for the utility of RWE for all stakeholders in medicine adoption (regulators, payors, prescribers and patients)Citation8, as patient registries, which are used for analysis of effectiveness for subgroups that cannot be included in an RCT, cost-effectiveness analysis and evidence-based medicine, cannot deviate from existing current diagnosis and management practices. This is especially important in rare diseases, for which patient registries are often fragmented across global territories, and this lack of standardization limits the applicability and interpretation of findings.

Three existing definitionsCitation10–12,Citation17,Citation18 specified that RWD are data relating to patient health status and/or the delivery of health care, and two also stated that RWD comes from a variety of sourcesCitation10–12,Citation18, while oneCitation10–12 specified these sources in detail. In contrast, the generated definition describes the characteristics of RWE itself as employing primary or secondary data collection in an unselected and representative disease population. As with the description of characteristics, the generated definition moves towards pragmatic utility by offering a synthesis of existing meanings in units of information that can be used as a decision-making heuristic during medical planning and guideline development.

Outcomes

The expanded version of the generated definition provided a set of outcomes in the form of stakeholder-specific endpoints, including effectiveness, safety, QoL and healthcare utilization. Existing definitions limited outcomes to treatment effectsCitation10–12 and the usage and potential risks/benefits of a medical productCitation13,Citation17. While there is some overlap, all existing definitions omitted QoL and healthcare utilization as specific outcomes. Healthcare utilization is a construct generally only used by payors, making it less likely to be mentioned in definitions generated by regulatory bodies. However, QoL is a construct that is used by all stakeholders and most importantly, is recognized as a construct of special importance to patients given that it characterizes patients’ lived experience of disease and health conditions rather than conceptualizing physiological outcomes that may be of more significance to researchers and clinicians. Patient centricity is a challenge in the pharmaceutical industry, especially regarding the movement from a medicine-centered modelCitation38; therefore, there is utility in specifying it in definitions of RWE. Additionally, the generation of regulatory grade QoL RWE in time for regulatory approval that meets the decision-making criteria for downstream stakeholders has the potential to reduce time required for maximal medicine adoption.

Delineated boundaries

All existing definitions except that from the FDA and the generated definition specified that RWE should be based on data collected outside an RCT. This is perhaps the most well-known criteria for the classification of RWE, possibly due to the ability of RWE studies to collect data on groups routinely excluded from RCTs. While this can, therefore, be understood as a clearly delineated boundary, there is little discussion in the literature regarding what may constitute other boundaries of RWE. The MHRA specified that RWE can be generated using data collected from wearable devices, specialized/secure websites, or tablets, which offers some understanding of what RWE can be but less guidance on what it is not. Clear delineation of this type of boundary may benefit greater collective understanding and implementation of RWE during drug development.

Limitations and further research

This study was limited by taking into account only the perspective of MAPPs. MAPPs have an ability to produce a pragmatically useful definition of RWE, as in their practice of medical affairs pharmaceutical medicine, they must generate and prepare dossiers of RWE that have utility for all external stakeholders involved in medicine adoption (regulators, payors, prescribers and patients)Citation8,Citation14. In terms of internal stakeholders, of those working in pharmaceutical companies, MAPPs are the most qualified and have the most relevant competencies developed during clinical experience to achieve thisCitation39,Citation40. However, it may be useful for a variety of regulators, such as the EMA, MHRA, FDA, Swiss Medic and others; payors; prescribers and patients to evaluate the definition in terms of suitability for use in each context. These external stakeholders make decisions about the extent to which RWE is used in practice for approval, reimbursement and treatment. There is a special emphasis on regulators’ opinion, as they are gatekeeper stakeholders who affect a treatment’s ability to progress to downstream stakeholders. Patients are the intended beneficiaries of new treatments and as such have ultimate say in whether RWE generated during drug development has been useful in improving lives. Validation of the findings with a group of MAPPs in other global regions, including emerging markets, may provide further insights. Additionally, validation with a larger group of MAPPs may confirm the findings of this study.

Conclusion

Currently, calls to increase the use of RWE during drug development, especially in time for regulatory use, are widespread, yet its regulatory use has been limited, attributable to a lack of clarity and consensus about its definition. The definition generated here promotes the regulatory use of RWE due to its greater conceptual maturity compared to existing regulatory definitions. Adopting this definition may increase understanding and implementation of RWE during medicines regulation and drug development and may aid the development and standardization of RWE frameworks and quality standards.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The author received no funding for this work.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Dr Ravi Jandhyala is a visiting senior lecturer at the Centre for Pharmaceutical Medicine Research at King’s College London and is responsible for research into real-world evidence approaches and is the founder and CEO of Medialis Ltd, a medical affairs consultancy and contract research organization involved in the design and delivery of real-world evidence in the pharmaceutical industry. The Jandhyala method was developed by Dr Jandhyala but is free of commercial licensing restrictions and while used as part of proprietary methodology, is not a direct means of commercial gain for the author.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

The author was involved in the conception, design, and analysis and interpretation of the data; the drafting of the paper and revising it critically for intellectual content; and the final approval of the version to be published. The author agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work. The author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted, and any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Favorable ethical opinion was granted by the King’s College London Research Ethics Committee (Reference number: MRA-21/22-26399). All participants gave written informed consent before taking part in the study.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank members of the MAPP advisory board, Dr Andy Pain, Dr Lisa Moore-Ramdin, Dr William Spencer, Dr Daniel Franks, Dr Gerd Möller, Dr John Bolodeoku, Dr Daniel A Thomas, Dr Timir Patel, Dr Raj Rout and Professor Peter Stonier for participating in the study. Dr Omolade Femi-Ajao contributed to the study through the provision of study management and Mohammed Kabiri provided data analytics, both as part of their roles as employees of Medialis Ltd. Lauri Naylor contributed to the article through the provision of medical writing and editing services as part of her role as an employee of Medialis Ltd.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

- H.R.34 – 114th Congress (2015–2016): 21st Century Cures Act. (2016, December 13). https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/34.

- Lokugamage AU, Simpson FK, Chew-Graham CA. Patient commentary: How power imbalances in the narratives, research, and publications around long Covid can harm patients. BMJ. 2021;373:n1579.

- Bolislis WR, Fay M, Kühler TC. Use of real-world data for new drug applications and line extensions. Clin Ther. 2020;42(5):926–938.

- Beaulieu-Jones BK, Finlayson SG, Yuan W, et al. Examining the use of real-world evidence in the regulatory process. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;107(4):843–852.

- Flynn R, Plueschke K, Quinten C, et al. Marketing authorization applications made to the european medicines agency in 2018–2019: What was the contribution of real-world evidence? Clin Pharma Therapeut. 2022;111(1):90–97.

- Jandhyala R. The effect of adding real-world evidence to regulatory submissions on the breadth of population indicated for rare disease medicine treatment by the European Medicines Agency. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2022;15(1):36.

- Ramamoorthy A, Huang SM. What does it take to transform real-world data into real-world evidence? Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;106(1):10–18.

- Jandhyala R. A medicine adoption model for assessing the expected effects of additional real-world evidence (RWE) at product launch. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(9):1645–1655.

- Cave A, Kurz X, Arlett P. Real-world data for regulatory decision making: challenges and possible solutions for Europe. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;106(1):36–39.

- Consultation document: MHRA draft guidance on randomised controlled trials generating real-world evidence to support regulatory decisions. GOV.UK. 2022; [cited 2022 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/mhra-draft-guidance-on-randomised-controlled-trials-generating-real-world-evidence-to-support-regulatory-decisions/consultation-document-mhra-draft-guidance-on-randomised-controlled-trials-generating-real-world-evidence-to-support-regulatory-decisions.

- MHRA guidance on the use of real-world data in clinical studies to support regulatory decisions. GOV.UK. 2022; [cited 2022 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/mhra-guidance-on-the-use-of-real-world-data-in-clinical-studies-to-support-regulatory-decisions/mhra-guidance-on-the-use-of-real-world-data-in-clinical-studies-to-support-regulatory-decisions.

- MHRA guideline on randomised controlled trials using real-world data to support regulatory decisions. GOV.UK. 2022; [cited 2022 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/mhra-guidance-on-the-use-of-real-world-data-in-clinical-studies-to-support-regulatory-decisions/mhra-guideline-on-randomised-controlled-trials-using-real-world-data-to-support-regulatory-decisions.

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Real world evidence and patient reported outcomes in the regulatory context. Published online 2021; [cited 2022 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/real-world-evidence-and-patient-reported-outcomes-in-the-regulatory-context.pdf.

- Jandhyala R. The multiple stakeholder approach to real-world evidence (RWE) generation: observing multidisciplinary expert consensus on quality indicators of rare disease patient registries (RDRs). Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(7):1249–1257.

- Armstrong RA, Mouton R. Definitions of anaesthetic technique and the implications for clinical research. Anaesthesia. 2018;73(8):935–940.

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. NICE real-world evidence framework; Corporate document [ECD9]. 2022; [cited 2022 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/corporate/ecd9/chapter/overview.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Framework for FDA’s Real-World Evidence Program. 2018; [cited 2022 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/120060/download.

- European Medicines Agency. EMA Regulatory Science to 2025. 2020; [cited 2022 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/ema-regulatory-science-2025-strategic-reflection_en.pdf.

- Patino CM, Ferreira JC. Inclusion and exclusion criteria in research studies: definitions and why they matter. J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(2):84.

- Morse JM, Mitcham C, Hupcey JF, et al. Criteria for concept evaluation. J Adv Nurs. 1996;24(2):385–390.

- Zumstein N, Riese F. Defining severe and persistent mental illness – a pragmatic utility concept analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:648.

- Pfadenhauer LM, Mozygemba K, Gerhardus A, et al. Context and implementation: a concept analysis towards conceptual maturity. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2015;109(2):103–114.

- Setia S, Ryan NJ, Nair PS, et al. Evolving role of pharmaceutical physicians in medical evidence and education. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:777–790.

- Neutral theory: a conceptual framework for construct measurement in clinical research. (Pre-print)

- Jandhyala R. A novel method for observing proportional group awareness and consensus of items arising from list-generating questioning. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(5):883–893.

- Jandhyala R. Delphi, non-RAND modified Delphi, RAND/UCLA appropriateness method and a novel group awareness and consensus methodology for consensus measurement: a systematic literature review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(11):1873–1887.

- Jandhyala R. Development of a definition for medical affairs using the Jandhyala method for observing consensus opinion among medical affairs pharmaceutical physicians. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:842431. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2022.842431

- Jandhyala R. PAC-19QoL: design, validation and implementation of the post-acute (long) COVID-19 quality of life (PAC-19QoL) instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):229.

- Damy T, Conceição I, García-Pavía P, et al. A simple core dataset and disease severity score for hereditary transthyretin (ATTRv) amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2021;28(3):189–198.

- Freedman S, de-Madaria E, Singh VK, et al. A simple core dataset for triglyceride-induced acute pancreatitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022;39(1):37–46.

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82.

- Leese J, Li LC, Nimmon L, et al. Moving beyond “Untl saturation was reached”: critically examining how saturation is used and reported in qualitative research. Arthritis Care Res. 2021;73(9):1225–1227.

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine; 1967.

- Forsyth D. 2009. Delphi technique. In: Levine J Hogg M, editors. Encyclopedia of group processes and intergroup relations. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; pp. 195–197.

- Hills TT, Noguchi T, Gibbert M. Information overload or search-amplified risk? Set size and order effects on decisions from experience. Psychon Bull Rev. 2013;20(5):1023–1031.

- Storm NE, Chang W, Lin TC, et al. A Novel case study of the use of real-world evidence to support the registration of an osteoporosis product in China. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2022;56(1):137–144.

- Varnai P, Davé A, Farla K, et al. The evidence reveal study: exploring the use of real-world evidence and complex clinical trial design by the european pharmaceutical industry. Clin Pharma Therapeut. 2021;110(5):1180–1189.

- Du Plessis D, Sake JK, Halling K, et al. Patient centricity and pharmaceutical companies: is it feasible? Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2017;51(4):460–467.

- Jandhyala R. Professional qualifications of medical affairs pharmaceutical physicians and other internal stakeholders in the pharmaceutical industry. F1000Res. 2022;11:813.

- Jandhyala R, Rout R. Observing expert opinion of medical affairs pharmaceutical physicians on the value of their clinical experience to the pharmaceutical industry using the Jandhyala method. Curr Med Res Opin. 2023. DOI:10.1080/03007995.2023.2165814.