Abstract

Background

Medical affairs pharmaceutical physicians (MAPPs) are at risk for low work-related quality of life (WRQoL). The aim of this study was to develop, validate and implement the first WRQoL instrument for this population.

Methods

A prospective observational cohort clinical study, the Medical Affairs Pharmaceutical Physician Work-related Quality of Life (MAPPWrQoL) Instrument Development and Patient Registry (MAPPWrQoLReg), was registered in November 2021 (NCT05123846). Thirteen MAPPs and 12 non-MAPPs participated in development and validation between December 2021 and January 2022. Development used the Jandhyala method for observing proportional group awareness and consensus. Discriminant validity analysis used the WRQoL Scale as a reference standard and assessed whether the instrument could differentiate between the groups. Twelve MAPPs and 12 non-MAPPs self-reported their WRQoL in the registry each month from February 2022. Recruitment and data collection are ongoing; 6-month data between February 2022 and August 2022 are reported here.

Results

Two participants were excluded from the registry. Chi-squared analysis showed a significant difference between the MAPPWRQoL instrument and WRQoL Scale (p = 1.029e-08) with acceptable sensitivity (89.19%) and specificity (75.00%). There were significant between-group differences for total scores at each follow-up (p = .003; n = 6 questions). Chi-squared analysis showed a significant difference between MAPPs’ and non-MAPPs’ ability to answer MAPPWRQoL instrument items (p = .002629), with acceptable sensitivity (91.9%) and near-acceptable specificity (66.7%). MAPPs’ WRQoL did not change significantly over 6 months.

Conclusion

Discriminant validity of the 39-item MAPPWRQoL instrument was confirmed. The Jandhyala method successfully developed and validated a specific WRQoL instrument and may be applied to similar populations, such as junior doctors and UK general practitioners.

Introduction

The pharmaceutical industry’s dual context with tensions between patient and commercial interestsCitation1 varies from the patient-centric environment in which pharmaceutical physicians were trained and gained clinical experience, subjecting them to a unique set of work-related stressorsCitation2. Workplace ethical climate influences work-related quality of life (WRQoL)Citation3, and the pharmaceutical industry is a complex ethical environment for pharmaceutical physiciansCitation1, having received scrutiny for promotional activities, gifts and payments to physiciansCitation4,Citation5 and the pricing and reimbursement of orphan drugsCitation6. Interpersonal factors also pose a risk to medical affairs pharmaceutical physicians’ (MAPPs’) WRQoL, as under-estimationCitation7 and under-recognitionCitation8 of work contribution, often experienced by MAPPsCitation9, has been shown to impair WRQoL. As MAPPs have unique value to pharmaceutical companiesCitation10 and patientsCitation3,Citation11, and poor WRQoL has been shown to be related to intention to leave workCitation12, it is beneficial to safeguard WRQoL in this group. Intervention has been shown to improve WRQoLCitation13, so it is worthwhile to monitor WRQoL in MAPPs to identify candidates suitable for intervention.

Measures of work-related quality of life

Widespread lack of agreement on a definition of WRQoL and the constructs it representsCitation14 makes determining an appropriate way to measure MAPP WRQoL difficult. An a priori method is generally used to develop WRQoL scales, which are based on diverse models, such as Karasek’s job demand-control modelCitation15,Citation16 and Seligman’s positive psychologyCitation17,Citation18. Additionally, although scales may measure subjective wellbeing in a work context, they vary in scope, with some including general wellbeing and home-work interface in addition to the work contextCitation19 and others excluding wellbeing at home as a separate constructCitation18. Despite this, scales measure some of the same domains, such as job satisfaction. The omission of wellbeing outside of work from a WRQoL tool may be problematic, as factors such as leisure satisfaction may influence employee QoL, and spill-over from work to home life has been related to WRQoL reliably in the literature, especially in specific contextsCitation14,Citation20.

The role of specific work contexts in work-related quality of life

Variation in work-related wellbeing has been observed between professions and between urban and rural workersCitation21,Citation22. Additionally, some approaches to workplace wellbeing have recognized interventions as being more effective at the organizational than individual levelCitation16. This suggests a role of context in WRQoL, supported by research linking various work-related wellbeing constructs to quality of work (work intensity, job design, social conditions, and physical conditions) and quality of employment (training opportunities, career advancement, job security, employability, work-life conflict, and income satisfaction)Citation23. The impact of specific types of work on physical health may influence employee QoL, and the job demands of specific types of work may influence employee QoL for different reasonsCitation24–28. Thus, a variety of specific tools for measuring WRQoL have been developed.

Specific measures of work-related quality of life

Specific measures exist for workers subject to specific inherent and/or structural conditions likely to have a negative impact on their WRQoL. Generic constructs such as job and organizational factors may be common to specific roles, but specific constructs naturally varyCitation14,Citation29. The relative contribution of empirical and methodological factors to the varying importance of wellbeing constructs in different contexts is unclear due to variation in outcome selection between studies, suggesting the potential utility of an inductive approach. Specific scales appear better able to detect variation in WRQoL than generic scales. A job-specific model of WRQoL explained 61.3% of variance in WRQoL, whereas a generic measure based on the job demand-control-support model explained 26%, 6%, and 8% of the variance in job satisfaction, psychological distress and burnout, respectivelyCitation30,Citation31. Further, assumed interaction effects predicted by the job demand-control model are only revealed when job-specific variables are included in the analysisCitation26. Therefore, specific scales are useful in measuring WRQoL in employees experiencing unique job contexts and demands, such as MAPPs. As there is no existing specific WRQoL measure for this group, the aim of this study was to design, validate and implement a MAPP-specific WRQoL instrument and monitor MAPPs’ QoL over 12 months to complement ongoing initiatives for improving medical professionals’ QoL.

Methods

Study design and conceptual basis

The Jandhyala method is a consensus method that has been designed to create highly accurate construct measurement instruments. Its utility arises from its operationalization of Neutral theory, which ensures the inclusion of all relevant indicators and the exclusion of all irrelevant indicators. This optimizes the generated instrument’s sensitivity and specificity, especially for detecting variation in unique populations and contexts that are poorly served by generic tools due to their exclusion of constructs of importanceCitation32. It has been used to develop and validate a range of scales in populations requiring specific construct measurement instruments, including the PAC19QoL, which has been translated into three languages and implemented in registries in the respective countriesCitation10,Citation33,Citation34. The Jandhyala method is a novel approach that has been differentiated from existing consensus generating methodologiesCitation35. A systematic literature review showed its validation against Delphi, non-Rand modified Delphi and the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method and its uniqueness in observing rather than forcing consensus as well as measuring awareness of subject matter among expertsCitation36.

Scale development using the Jandhyala method is achieved by observing levels of awareness and consensus relating to a list of indicators solicited via two anonymous online surveys. Responses to the Awareness Round (1) survey are used to assess knowledge awareness by calculating the frequency of each coded item in relation to the frequency of the most commonly occurring coded item overall (the Awareness Index). The Consensus Index is the proportion of participants supporting the inclusion of an item, with inclusion indicated by a score of 4 or 5 on the Likert scale (agree or strongly agree). The AI and CI are both continuous variables and are categorized into awareness and consensus scores for further analysis.

Participants and recruitment

Recruitment took place via social media platforms, professional networks, and direct contact with pharmaceutical companies, membership organizations, and medical affairs companies. A total of 13 medically qualified MAPPs with specialty training in medical affairs pharmaceutical medicine and work experience in an industry-based pharmaceutical company were recruited to the study. Twelve non-MAPPs working in the pharmaceutical industry as clinical development professionals at the time of study were recruited via professional networks to validate the instrument. In accordance with international regulations, favorable ethical opinion for the MAPPWRQol instrument development, validation and registry was granted by the King’s College London Research Ethics Committee (MRA-21/22-28431) and the NHS Health Research Authority London – Riverside Research Ethics Committee (21/PR/1397).

Sample size

The Jandhyala method is an inductive approach to scale development. Awareness and consensus metrics provide quantitative support for conceptualization and validity of the construct measure with the unit of analysis at the item level. Participants generate at least three items to provide sufficient numbers to justify conclusions. As it is an inductive approach that aims to generate underlying principles, parallels can be drawn to Grounded TheoryCitation37, and methods for sample size calculation for qualitative methodologies, namely data saturation, can therefore appropriately be used.

Data saturation is defined as the point at which there is no empirical merit of collecting further data from new participants. The failure of further data collection to add anything meaningful to results was operationally defined in this study as no new items generated by a minimum of one participant; at this point, saturation was said to have been reached. Saturation was established via the recruitment procedure, which dictated that sample size increase until this condition was fulfilled. Previous, conceptually similar applications of the Jandhyala method suggested that a sample size of nine to 12 is necessary to achieve exhaustive data capture, broadly in line with recommended numbers for expert panels in consensus studiesCitation38 and sufficient to generate enough data to meet the conditions of data saturation. Sample size was in line with other qualitative studies using data saturation to determine exhaustiveness of data captureCitation39. Per the principles of Grounded Theory, conclusions are in a process of ongoing development in light of continual data collection. The MAPPWRQoL Instrument has been implemented in a registry to which further MAPPs are being recruited on an ongoing basis to accommodate this need.

Development of the MAPPWRQoL instrument

Development and validation of the MAPPWRQoL instrument took place between 1 December 2021 and 5 January 2022. Development was achieved by identifying indicators specific to MAPP WRQoL using the Jandhyala method. In Awareness Round 1, MAPPs were asked a series of demographic questions as well as a list generating question to elicit WRQoL indicators. They were asked to provide at least three and up to 50 free text responses, each referring to one indicator affecting their WRQoL. Participant responses were refined into a list of internally cohesive and mutually exclusive WRQoL indicators by two research analysts through a process of content analysis and open coding. Codes were attributed to their related participant response by one research analyst and confirmed by a second. Participants who completed Awareness Round (1) were invited to participate in Consensus Round (2). In this round, aggregated coded responses were presented to MAPPs in a further anonymized online survey. Participants were asked to rate their agreement with the inclusion of each item in the instrument on a 5-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree.

Validation of the MAPPWRQoL instrument

Discriminant validity of the MAPPWRQoL instrument was established using two methods. First, validity was tested using the WRQoL ScaleCitation26 as a reference standard. Second, the instrument was validated by determining its ability to differentiate between MAPPs and non-MAPPs using a control group of 12 individuals in employment at the time of study recruited via researchers’ networks. Participant demographics were recorded for the study and control populations, and they were both required to complete the same questionnaire.

Implementation of the MAPPWRQoL instrument and 6-month data

A prospective observational cohort clinical study, the Medical Affairs Pharmaceutical Physician Work-related Quality of Life (MAPPWrQoL) Instrument Development and Patient Registry (MAPPWrQoLReg), was registered on clinicaltrials.gov in November 2021 (NCT05123846) with ongoing recruitment and monitoring estimated to be completed in October 2026. The finalized MAPPWRQoL instrument was hosted on a secure online system in February 2022, and newly recruited participants as well as participants from the development and validation stage who wanted to remain in the study were enrolled into the registry. Participants were allocated an identification record number and self-reported their WRQoL at monthly intervals. Subject to completion rate, data from 6 months between 28 February 2022 and 28 August 2022 have been presented here.

Statistical analysis

Development of the MAPPWRQoL instrument

Descriptive statistics were obtained for demographic variables at baseline from registry data. Development of the instrument relied on awareness and consensus metrics generated from Likert scale responses during the Jandhyala method. Items with a CI ≥ 0.51 at Consensus Round (2) were included in the final MAPPWRQoL instrument.

Validation of the MAPPWRQoL instrument

Discriminant validity was established using two methods. First, validity using the WRQoL ScaleCitation26 as a reference standard was determined by chi-squared analysis of the difference in unique items between the tools with statistical significance set at p < .05. Second, validity in terms of the MAPPWRQoL instrument’s ability to discriminate between MAPPs and non-MAPPs was tested using (a) a Wilcoxon signed-rank test for total QoL scores for both groups at each follow-up; (b) chi-squared analysis of participants’ ability to answer items. A frequency occurrence of zero at f(x) ≥ 5 (that is, five participants being unable to answer a question) was considered an inability to answer the question. Scores were converted to sensitivity and specificity indexes, with acceptable limits set arbitrarily at 80% and 70%, respectively. Positive and negative predictive values, false discovery rate and false omission were calculated.

Implementation of the MAPPWRQoL instrument

Data from 6-month follow-up of MAPPs and non-MAPPs were analyzed using univariate linear regression and GLM univariate poisson regression analyzes. All statistical analyzes were conducted in R (version 3.6.3).

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 13 MAPPs (16.67% female) participated in the development and validation of the MAPPWRQoL instrument. To validate the MAPPWRQoL instrument, 12 non-MAPPs (25.00% female) participated. At baseline measurement, a total of 24 participants took part in the MAPPQoL registry; MAPPs and non-MAPPs each had 12 participants. One MAPP was lost to follow-up before participating in the registry, and one non-MAPP was excluded at analysis due to non-response. In the control group, there was an attempt for an age-match with MAPP demographics (). Both groups had a similar sociodemographic background, with the control group being composed of academics, those in the professions and those employed at large commercial entities. Assessment of baseline characteristics showed that the groups did not vary significantly, except regarding breadwinner status (MAPPs = 41.67% non-MAPPs = 75.00%; p = .0001199).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics.

Development of the MAPPWRQoL instrument

In total, 13 MAPPs were included in the development of the MAPPWRQoL instrument. Saturation of unique WRQoL indicators was reached by nine participants (Supplemental Appendix A). Forty-seven unique indicators were generated by Awareness Round (1) of the Jandhyala method. Of the 47 indicators, 25 (53%) had an AI > 0.50. After the presentation of the list of indicators to participants in Consensus Round (2), 40 (85%) achieved a relative degree of prompting. Eight indicators failed to reach the cut-off point of CI > 0.50 and were excluded, leaving a total of 39 indicators, which were converted to variables for inclusion in the MAPPWRQoL instrument (Supplemental Appendices B and C).

Validation of the MAPPWRQoL instrument

Validation using the WRQoL Scale as a reference standard

There were statistically significant differences between the WRQoL Scale and the MAPPWRQoL instrument (Χ-squared = 32.785, df = 1, p = 1.029e-08; ). Sensitivity (89.19%) and specificity (75.00%) were within expected limits for acceptable discriminant validity and showed the greater Neutrality of the MAPPWRQoL for detecting WRQoL in this specific population.

Table 2. Chi-squared tabulation of unique items in the MAPPWRQoL instrument and WRQoL Scale (Χ-squared = 32.785, df = 1, p = 1.029e-08).

Ability of the MAPPWRQoL instrument to differentiate between MAPPs and non-MAPPs

Validation of the MAPPWRQoL instrument in respect of its ability to differentiate MAPPs and non-MAPPs showed statistically significant differences between MAPPs’ and non-MAPPs’ QoL scores using the Wilcoxon signed rank test (p = .003; n = 6 questions). However, upon the removal of the six questions, QoL scores from the remaining 33 questions were not able to deduce a statistical difference between MAPPs and non-MAPPs. Further, there was a statistically significant difference in MAPPs’ and non-MAPPs’ ability to respond to MAPPWRQoL questions (Χ-squared = 9.0485, df = 1, p = .002629; ). Sensitivity (91.9%) was within accepted limits for the differentiation of MAPPs from non-MAPPs, and specificity (66.7%) was just outside the accepted limit. Positive predictive value (94.4%), false discovery rate (5.6%), false omission rate (42.9%) and negative predictive value (57.1%) followed from these results as expected, with guidance ratios at 2.757 (positive), 0.122 (negative) and 22.667 (diagnostic odds ratio).

Table 3. Chi-squared tabulation of MAPPWRQoL by participants’ ability to respond to questions.

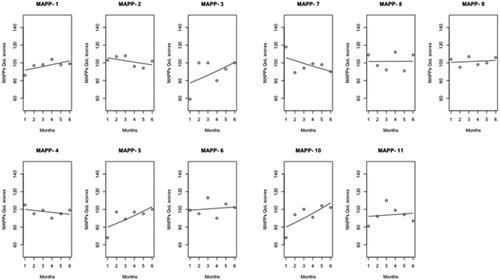

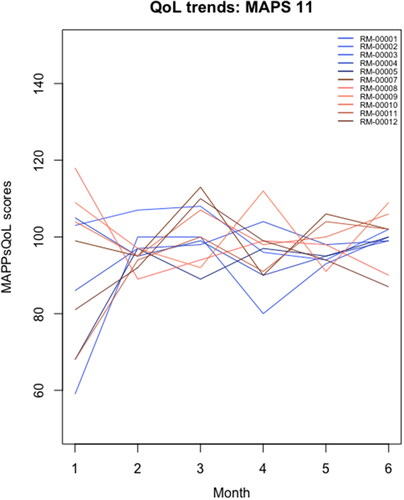

Implementation of the MAPPWRQoL instrument

Average QoL scores were recorded for MAPPs: 94.08 (sd = 21.66) and non-MAPPs: 74.08 (sd = 29.9). No missing QoL scores were observed among MAPPs. One non-MAPP participant demonstrated a total QoL score at zero, with none of the 39 questions scored. After exclusion, the non-MAPP average QoL score was at 80.8 and sd = 19.6. Density plots have been shown in the appendices (Supplemental Appendix D). Linear univariate regression fit for average MAPPWRQoL instrument scores at each month () showed variation between MAPPs, with GLM univariate poisson regression fit showing a tendency for MAPPWRQoL instrument scores to converge around 100 at month 6 (). The information collected from the generic tool had a sensitivity of 15.4% and specificity of 84.6% for MAPPs’ QoL measurements, with false positive (18.2%) and false negative (81.8%) rates following from these.

Discussion

The 39-item MAPPWRQoL was developed using the Jandhyala method for observing proportional group awareness and consensus by soliciting QoL indicators self-reported by MAPPs. Discriminant validity was largely confirmed, suggesting that the MAPPWRQoL is a preferred means for detecting variation in WRQoL in this population compared to existing generic scales. Implementation of the MAPPWRQoL in a dedicated registry showed some variation in WRQoL between MAPPs, but WRQoL did not change significantly for participants over the 6-month period.

Assessment of the overall distribution of awareness of QoL indicators among MAPPs demonstrated high initial awareness of 25 (53%) indicators, with 39/47 (83%) meeting the consensus threshold for inclusion after relative prompting. This level of awareness and prompting can be understood to arise from the generally wide conceptual boundaries of WRQoL, especially in terms of its subjectivity, and the relative balance of resources available to complete the survey. Most indicators met the consensus threshold after prompting, suggesting a general agreement among MAPPs as to the workplace characteristics affecting their QoL. This and registry data responses were generally indicative of the internal consistency of the instrument. Saturation was in line with expected limits based on previous experience of the Jandhyala method.

Like other specific scales and contextsCitation14,Citation29,Citation30,Citation40, the scale incorporated both generic and specific domains. Generic domains included in the MAPPWRQoL instrument were job characteristics (flexible hours, working hours, clear roles and responsibilities and so on), workplace characteristics (company, culture, workplace relationships and so on), job satisfaction, leisure satisfaction and health and wellbeing. These were generally in line with existing models of WRQoL and existing scalesCitation15–17,Citation23,Citation26, although an important distinction is a fact that MAPPs viewed their QoL as being influenced by both work and home factors, distinguishing this instrument from those that focus on a work contextCitation18.

MAPP-specific items in the MAPPWRQoL included work-life balance, fear of reprisal, pressure to approve materials, pressure from the commercial team, job satisfaction in relation to patient benefit, and distribution of decision-making power among the team. The inclusion of these items in the instrument may explain the significant difference in item QoL score between MAPPs and non-MAPPs by Wilcoxon signed rank test. These items generally support the idea that MAPPs are at the forefront of the pharmaceutical industry’s ethical divide and the associated risk this poses to their WRQoL. Of particular note, all MAPPs reported without prompting that seeing patients benefit from their work was a significant factor in their WRQoL. This was in line with MAPPs’ clinical experience and training in terms of its patient-centricity as well as the risk to their WRQoL due to value mismatch with the ethical climate of the pharmaceutical industry. It also supports the need to safeguard this unique population due to their close alignment with patient interests.

Additionally, the inclusion of work-life balance may be transferrable to other professions, for example, due to its similarity to ‘spill-over to home’Citation14. Ambiguity of constructs in the literature due to varying definitions complicates interpretation. A standardized lexicon of WRQoL outcomes would benefit ongoing research in a wider sense by allowing closer comparative analysis of constructs between studies to understand the extent of differentiation between specific contexts with regard to their impact on WRQoL. Further psychometric analysis of the WRQoL with increased sample sizes will be possible with the ongoing recruitment and collection of data in the registry to clarify whether this item should be considered independent from generic domains such as job characteristics and whether it relates to a specific characteristic of MAPP and/or professional work.

Though the newly designed instrument has shown significant differences from the WRQoL Scale, MAPPs did not show substantial changes in their QoL scores over a 6-month period. It was within the expectation that MAPPs’ QoL scores would fluctuate each month over the 6-month period. However, their scores were likely to remain stagnant within their individual respective range. Statistical findings from the Wilcoxon paired test, descriptive analysis and univariate regressions supported this. It was beyond the scope of the study to determine reasons for fluctuations; however, this may allow for the identification of appropriate intervention if necessary (e.g. whether it should be at the organizational or individual level) and may provide evidence as to whether there is a need for widespread culture change within the pharmaceutical industry.

Significance and future work

This work demonstrates a novel application of the Jandhyala method as a means of developing a scale to measure WRQoL in specific populations. This method can be applied to other specialist workforces at risk of poor WRQoL due to job demands specific to their unique contexts. It may be especially useful in clinical workers who, like MAPPs, have transitioned to a different work context, such as junior doctors and general practitioners in the UK who have had to adapt to increasing administrative and financial responsibility, with both of these groups showing risk of poor WRQoL and declining numbers in recent years.

Limitations

Although conditions for discriminant validity in terms of the sensitivity and specificity of the MAPPWRQoL instrument were met when using the generic WRQoL instrument as a reference standard, its ability to differentiate between MAPPs and controls with regard to specificity was just outside of the predefined accepted limit. There was a possibility of selection bias due to the sampling method for the selection of the control group, which may have resulted in a high proportion of control group workers in the professions and associated fields, which may be expected to have more similarity to the MAPP context than a wider variety of workplaces. In this case, we could expect that our analysis may have underestimated the discriminant validity of the instrument, with greater sensitivity and specificity likely to result from comparison with a more diverse control group. Statistical calculation of internal consistency, test-re-test reliability and so on were beyond the scope of this study, in part due to the number of recruited participants at the time of the study. However, further statistical and psychometric analysis will be possible with greater numbers of MAPPs recruited to the registry, which is ongoing.

Conclusions

Discriminant validity of the 39-item MAPPWRQoL instrument was confirmed using the WRQoL Scale as a reference standard. The MAPPWRQoL instrument successfully differentiated between MAPPs and non-MAPPs in relation to their ability to answer included items. The Jandhyala method is a useful method for developing and validating a specific WRQoL instrument and may be applied to populations working in similar contexts, such as junior doctors and general practitioners in the UK.

Transparency

Author contributions

The author conducted the study and developed and approved the manuscript. The author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted, and any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Favorable ethical opinion for the MAPPWRQol instrument development, validation and registry was granted by the King’s College London Research Ethics Committee (MRA-21/22-28431) and the NHS Health Research Authority London – Riverside Research Ethics Committee (21/PR/1397). All participants gave written informed consent before taking part in the study.

Supplemental Material

Download Rich Text Format File (406.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the MAPP advisory board, John Bolodeoku, Phillip Cruz, Judith Livingstone, Lisa Moore-Ramdin, Pundalik Nayak, Andy Pain, Raj Rout, Jan Sabbat, Will Spencer, Peter Stonier, Guy Yeoman and Maciej Zatonski for participating in the study. The author would also like to thank the control group participants for their contribution. Additionally, gratitude is extended to Omolade Femi-Ajao for study management, Mohammed Kabiri for data analytics and Lauri Naylor for medical writing, all of Medialis Ltd.

Declaration of funding

The author received no funding for this work.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Dr Ravi Jandhyala is a visiting senior lecturer at the Centre for Pharmaceutical Medicine Research at King’s College London and is responsible for research into real-world evidence approaches. He is also the founder and CEO of Medialis Ltd, a medical affairs consultancy and contract research organisation involved in the design and delivery of real-world evidence in the pharmaceutical industry. No conflict of interest has been registered from the author. The Jandhyala method was developed by Dr Jandhyala but is free of commercial licensing restrictions and while used as part of proprietary methodology, is not a direct means of commercial gain for the author.

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they are country medical director Moderna. Another reviewer has disclosed that they are working at Medison Pharma as Medical Director CEE and is also owner of Alcon shares. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

References

- Morris T, Brostoff JM, Stonier PD, et al. Evolution of ethical principles in the practice of pharmaceutical medicine from a UK perspective. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1525.

- Jandhyala R, Rout R. Observing expert opinion of medical affairs pharmaceutical physicians on the value of their clinical experience to the pharmaceutical industry using the Jandhyala method. Curr Med Res Opin. 2023. DOI:10.1080/03007995.2023.2165814

- C. Fradelos E, Alexandropoulou CA, Kontopoulou L, et al. The effect of hospital ethical climate on nurses’ work-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Forum. 2022;57(2):244–251.

- Mitchell AP, Trivedi NU, Gennarelli RL, et al. Are financial payments from the pharmaceutical industry associated with physician prescribing? Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(3):353–361.

- Maeda H. Medical affairs in pharmaceutical companies and related pharmaceutical regulations in Japan. Front Med. 2021;8:672095.

- Berdud M, Drummond M, Towse A. Establishing a reasonable price for an orphan drug. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2020;18:31.

- Duracinsky M, Marcellin F, Cousin L, et al. Social and professional recognition are key determinants of quality of life at work among night-shift healthcare workers in Paris public hospitals (AP-HP ALADDIN COVID-19 survey). PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0265724.

- Ricciardelli R, Carleton RN. A qualitative application of the job demand-control-support (JDCS) to contextualize the occupational stress correctional workers experience. J Crime Justice. 2022;45(2):135–151.

- Stonier PD, Silva H, Boyd A, et al. Evolution of the development of core competencies in pharmaceutical medicine and their potential use in education and training. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:282.

- Jandhyala R. Development and validation of the medical affairs pharmaceutical physician value (MAPPval) instrument. Pharm Med. 2022; 36(1):47–57.

- Jandhyala R. Development of a definition for medical affairs using the Jandhyala method for observing consensus opinion among medical affairs pharmaceutical physicians. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:842431.

- Algazlan N, Al-Jedai A, Alamri A, et al. Association between intention to leave work and quality of work-life of Saudi pharmacists. Saudi Pharm J. 2022;30(2):103–107.

- Cascales-Pérez ML, Ferrer-Cascales R, Fernández-Alcántara M, et al. Effects of a mindfulness-based programme on the health- and work-related quality of life of healthcare professionals. Scand J Caring Sci. 2021;35(3):881–891.

- Silarova B, Brookes N, Palmer S, et al. Understanding and measuring the work-related quality of life among those working in adult social care: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(5):1637–1664.

- Karasek RA. Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job design. Admin Sci Q. 1979;24:285–308.

- Cousins R, MacKay CJ, Clarke SD, et al. Management standards’ and work-related stress in the UK: practical development. Work Stress. 2004;18:113–136.

- Seligman M. 2002. Authentic happiness: using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

- Singh S, Aggarwal Y. Happiness at work scale: construction and psychometric validation of a measure using mixed method approach. J Happiness Stud. 2018;19(5):1439–1463.

- Van Laar DL, Edwards JA, Easton S. The work-related quality of life (QoWL) scale for healthcare workers. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60(3):325–333.

- Yuh J. The impact of affective commitment and leisure satisfaction on employees’ quality of life. Open Psychol J. 2022;15(1):e187435012205111.

- Vu TQ, Nguyen BT, Pham VNH, et al. Quality of work life in healthcare: a comparison of medical representatives and hospital pharmacists. Hosp Top. 2021;99(4):161–170.

- Kelly D, Schroeder S, Leighton K. Anxiety, depression, stress, burnout, and professional quality of life among the hospital workforce during a global health pandemic. J Rural Health. 2022;38(4):795–804.

- Steffgen G, Sischka PE, Fernandez de Henestrosa M. The quality of work index and the quality of employment index: a multidimensional approach of job quality and its links to Well-Being at work. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7771.

- Sezer B, Kartal S, Sıddıkoğlu D, et al. Association between work-related musculoskeletal symptoms and quality of life among dental students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):41.

- Jiménez-Arberas E, Díez E. Musculoskeletal diseases and disorders in the upper limbs and health work-related quality of life in Spanish sign language interpreters and Guide-Interpreters. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(15):9038.

- de Jonge J, Kompier MAJ. A critical examination of the demand-control-support model from a work psychological perspective. Int J Stress Manage. 1997;4(4):235–258.

- Salas-Vallina A, Alegre J, Fernández Guerrero R. Happiness at work in knowledge-intensive contexts: opening the research agenda. Eur Res Manage Business Econ. 2018;24(3):149–159.

- Howie-Esquivel J, Byon HD, Lewis C, et al. Quality of work-life among advanced practice nurses who manage care for patients with heart failure: the effect of resilience during the covid-19 pandemic. Heart Lung. 2022;55:34–41.

- Gafsou B, Becq MC, Michelet D, et al. Determinants of work-related quality of life in French anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg. 2021;133(4):863–872.

- Kim J h, Jang S N Seafarers’ quality of life: organizational culture, self-efficacy, and perceived fatigue. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(10):2150.

- McClenahan CA, Giles ML, Mallett J. The importance of context specificity in work stress research: a test of the demand-control-support model in academics. Work Stress. 2007;21(1):85–95.

- Jandhyala R. Concordance between the schedule for the evaluation of individual quality of life – direct weighting (SEIQoL-DW) and the EuroQoL-5D (EQ-5D). Measures of quality of life outcomes in adults with X-linked hypophosphatemia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;17:81.

- Damy T, Conceição I, García-Pavía P, et al. A simple core dataset and disease severity score for hereditary transthyretin (ATTRv) amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2021;28(3):189–198.

- Jandhyala R. Design, validation and implementation of the post-acute (long) COVID-19 quality of life (PAC-19QoL) instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):229.

- Jandhyala R. A novel method for observing proportional group awareness and consensus of items arising from list-generating questioning. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(5):883–893.

- Jandhyala R. Delphi, non-RAND modified Delphi, RAND/UCLA appropriateness method and a novel group awareness and consensus methodology for consensus measurement: a systematic literature review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(11):1873–1887.

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine; 1967.

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82.

- Forsyth D. 2009. Delphi technique. In: Levine J, Hogg M, editors. Encyclopedia of group processes and intergroup relations. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications, Inc. p. 195–197.

- Hussein S, Towers AM, Palmer S, et al. Developing a scale of care work-related quality of life (CWRQoL) for long-term care workers in England. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2):945.