Abstract

Objectives

To provide clinical characteristics and to quantify the number of patients receiving the extemporaneous combination of the calcium channel blocker amlodipine and the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor zofenopril in a real-world setting. This evidence can provide a snapshot of the potential users of the two molecules in a single pill combination (SPC).

Methods

Retrospective observational study using data from the IQVIA Italian Longitudinal Patient Database. Adult patients firstly prescribed with amlodipine and zofenopril between 1 July 2011 and 30 June 2020 were identified and demographic and clinical characteristics were extracted. Treatment adherence was evaluated as proportion of days covered (PDC). The potential number of patients eligible for a SPC was calculated.

Results

A population of 2394 hypertensive patients, mean age of 68.6 years ±12.7, 52.6% male were treated with amlodipine and zofenopril. The majority of patients (54.5%) were low adherent (PDC <40%), 25.9% were intermediate adherent and only 19.6% were high adherent (>80%) to therapy. Around 42,500 adult hypertensive patients were estimated to be prescribed the extemporaneous combination in 2019 in Italy, being potentially eligible for treatment with amlodipine and zofenopril SPC.

Conclusions

The administration of the extemporaneous combination of zofenopril and amlodipine in hypertensive patients is a common practice in Italy. The development of a SPC can be a viable treatment option to simplify therapy and to increase adherence in hypertensive patients who are already on the two monotherapies in combination.

Introduction

Hypertension is a chronic disease affecting over 1 billion people worldwide and is the major risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease, causing the death of over 8 million people every yearCitation1. In Italy, the reported hypertension prevalence ranges from 55% to 59% of the adult populationCitation2,Citation3. Unfortunately, in spite of therapeutic advances, improved efficacy and protective effects on cardiovascular outcomes, pharmacological treatment is often suboptimal and control of blood pressure (BP) is still inadequate in a large proportion of patientsCitation4. In this regard, poor adherence to antihypertensive therapy is a very common phenomenon in primary care, contributing to insufficient control of BP with relevant implications on the associated cardiovascular risk and financial burden for healthcare systemsCitation5.

Different types of interventions have been evaluated to optimize the level of adherence to BP lowering therapies: improvement in communication skills of healthcare professionals to establish effective therapeutic alliance with patients, patient empowerment, self-monitoring of BP (including telemonitoring), use of therapy reminders, caregiver support, simplification of the drug regimen including use of fixed dose combinationsCitation6.

With the aim of increasing adherence to antihypertensive therapy and enhance the benefits of individual antihypertensive agents, single-pill combinations (SPCs) of medications with complementary mechanisms of action have been developedCitation4. Indeed, 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines stated that the most effective treatment strategy to improve BP control should: 1) encourage the use of combination treatment in most patients, especially in the perspective of more stringent BP targets; 2) enable the use of SPC therapy for most patients to improve adherence to treatment; and 3) produce simplification of the treatmentCitation7. Concomitant administration of a calcium channel blocker (CCB) plus an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor is one of the recommended first-line combination therapies according to the 2018 ESC/ESH guidelinesCitation7.

Amlodipine is a long-acting, lipophilic, third generation dihydropyridinic CCB indicated for the treatment of hypertension and chronic stable angina, with a good safety profileCitation8. Amlodipine inhibits calcium influx into vascular smooth muscle cells, thus reducing vasoconstriction and decreasing peripheral vascular resistanceCitation9. Amlodipine is usually dosed once daily because of its long half-life at a starting dose of 5 mg, with a maximum daily dose of 10 mgCitation9. Several studies demonstrated the anti-hypertensive efficacy of amlodipine monotherapy in comparison to other agents, including diuretics, ACE inhibitors (ACEis) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)Citation9. In addition, amlodipine has also shown reduction in cardiovascular outcomesCitation10,Citation11. There is evidence that amlodipine is able to delay the progression of atherosclerosis, confer antioxidant protection and enhance NO productionCitation9.

The effectiveness and safety of the concomitant use of amlodipine in combination with ACEis have been consistently proven in several clinical trialsCitation12–15.

Zofenopril is a sulfhydryl ACE inhibitor, characterized by high lipophilicity, selective cardiac ACE inhibition, with antihypertensive, antioxidant, and cardioprotective properties, including an improved endothelial functionCitation16. There is a solid body of comparative data supporting the effectiveness and safety profile of zofenopril for the treatment of mild to moderate hypertension and ischaemic heart diseaseCitation17. The SPC zofenopril-hydrochlorothiazide 30/12.5 mg/day is approved for management of mild-to-moderate hypertension in different European countries. In Italy, the zofenopril-hydrochlorothiazide combination is approved for patients whose BP is not adequately controlled by monotherapy with zofenopril. In clinical trials comparing zofenopril-hydrochlorothiazide with each agent administered individually, resulted in a greater BP control provided by combination therapy, complemented by a favourable safety profileCitation18.

CCBs and ACEis have been shown to provide a synergistic BP lowering effect in combination, they are generally well tolerated and are associated with beneficial effects on organ damage and cardiovascular and renal events, and are also metabolically neutralCitation19. Despite the extensive body of literature on amlodipine and zofenopril, there is little evidence available on the combined use of these two agents. To the best of our knowledge, only one study has assessed this combination by pooling data from four randomized clinical trials through a post-hoc analysis in patients with acute myocardial infarctionCitation20.

Clinical trials support the use of antihypertensive SPCs in view of a better control of BP compared to initiating standard-dose monotherapyCitation21. Moreover, SPCs are associated with increased adherence, shorter time to BP control, and better cardiovascular outcomesCitation21. In addition, since hypertension is a complex disease involving multiple pathophysiological mechanisms and more ambitious targets than in the past are currently recommended, the use of SPCs is validCitation7. In particular, drugs with synergistic mechanisms of action are more rational as they permit a multitargeted approach with more chances to achieve effective BP control and fewer side effects compared to the use of high dose monotherapyCitation19.

Given that SPCs are recommended for most hypertensive patients,Citation7 it is important to provide a snapshot of their use in individual countries to obtain a reliable estimate of the prescribing patterns. The primary objective of the present work was to characterize hypertensive patients initiating the extemporaneous combination of amlodipine and zofenopril (AZ-EXC) in a real-world setting in Italy in a large, representative, population-based study. The secondary objective was to estimate, over a one-year period, the number of patients prescribed with AZ-EXC and calculate the potential users of a combination of the two molecules in a SPC (AZ-SPC).

Methods

Data source

The IQVIA Italian Longitudinal Patient Database (LPD) was the source of data for this retrospective observational cohort study. The IQVIA Italian LPD collects data from physician consultations (i.e. diagnoses and drug prescriptions according to the International Classification of Diseases 9th revision (ICD-9), and the Anatomical Therapeutic and Chemical (ATC) classification system, respectively), and medical and demographic information, thus providing a representative sample of routine care with general practitioners (GPs) in Italy. GPs contributing to the database of general practice were specifically trained to enter the data. The database consists of data from routinely collected records of about 1.2 million patients by around 900 GPs. The IQVIA Italian LPD has been shown to be a reliable source of information in previous studies for several diseases, including hypertensionCitation4,Citation22,Citation23.

Definition of cohorts

Incident users of AZ-EXC

In order to explore the primary objective, all patients starting treatment with AZ-EXC of “5 mg/10 mg amlodipine” (ATC code C08CA01) and “30 mg zofenopril” (ATC code C09AA15) during the selection period, 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2020, were included. The starting date of the first extemporaneous combination during the selection period was defined as the index date. Patients were excluded from the AZ-EXC cohort if: (1) they did not have a diagnosis of hypertension (ICD-9 codes 401xx and 402.xx) in the 12-month period preceding the index date; (2) had a previous prescription of AZ-EXC during the 6 months before the index date. The cohort of AZ-EXC incident users identified was then analysed in terms of demographic features, clinical characteristics, and adherence to treatment.

Prevalent users of AZ-EXC

For the secondary objective and to provide an estimate of the prevalence of AZ-EXC patients over a one-year period, all patients prescribed the extemporaneous combination of “5 mg/10 mg amlodipine” (ATC code C08CA01) and “30 mg zofenopril” (ATC code C09AA15) as single molecules during the year 2019 were identified. Patients were excluded if they did not have a diagnosis of hypertension in the 12-month period preceding the index date. The complete formula used to calculate prevalent users has been previously describedCitation23. This cohort would provide a real estimate at the national level of potential users of the AZ-SPC, i.e. patients who are already prescribed the two molecules and who would likely switch to a SPC regimen. The choice of the study period (year 2019) was done to avoid the possible bias in changing of prescriptions due to the pandemic, which is documented to have influenced diagnosis and new therapiesCitation24.

Sensitivity analysis

In addition to the AZ-EXC cohorts of incident and prevalent patients, we also analysed patients receiving AZ-EXC (SM + SPC) defined as: “5 mg/10 mg amlodipine” (ATC code C08CA01) and “30 mg zofenopril” prescribed as single molecule (ATC code C09AA15) or as a SPC containing the monotherapies of each drug with hydrochlorothiazide (ATC code C09BA15). In this sensitivity analysis, the cohorts of incident and prevalent AZ-EXC users (SM + SPC) were created to investigate possible differences with the corresponding AZ-EXC cohorts. This additional information provides a wider and clearer picture of the well-established use of the extemporaneous combination in current practice, although patients receiving the SPC containing hydrochlorothiazide [AZ-EXC (SM + SPC)] are not likely to be the target population for a potential amlodipine/zofenopril SPC. Indeed, patients who might benefit the most from introduction of the SPC are those who are currently being treated with AZ-EXC as single agents and who would switch from a two-pill to a one-pill treatment.

Study definitions

Adherence to therapy was defined as the degree to which patients take the medication as prescribed by their GPsCitation4. Adherence was assessed as proportion of days covered (PDC)–total days of supply of medication dispensed over the length of the corresponding follow-up, indicated by the Pharmacy Quality Alliance– as previously definedCitation23,Citation25. Additionally, it provides a more conservative estimate of adherence compared to other indicators if concomitant multiple medications are usedCitation26. The number of days supplied by each prescription was obtained by dividing the total amount of active drug in each prescription by the recommended defined daily dose (i.e. 5 mg for amlodipine and 30 mg for zofenopril)Citation23. Days of supply contributed to the numerator only when amlodipine and zofenopril overlapped. In addition, the stratification of incident users of amlodipine by dosage formulation (5 mg or 10 mg) prescribed over a six-month follow-up permitted the quantification of the number of patients prescribed the same dosage and how many switched to a different one.

Information extracted from the database

Information regarding AZ-EXC incident users (age, sex, body mass index–BMI, comorbidities, concomitant pharmacological treatments, and cardiologic visit referrals) were extracted from IQVIA Italian LPD, as described beforeCitation23.

Statistical analysis

General demographic and clinical characteristics of patients’ cohort and an overview of treatment adherence for incident users of AZ-EXC were given by descriptive statistics. Qualitative variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, while quantitative variables as mean values, standard deviation (SD), median, and first and third quartiles (Q1 and Q3). Low treatment adherence was classified when PDC was less than 40%, intermediate for PDC between 40% and 79%, and high for PDC of at least 80%. An estimation of the patients who could potentially be eligible for the treatment with AZ-EXC was calculated as previously describedCitation23. SAS software version 9.4Footnotei was used to performed statistical analyses on anonymized data.

Results

Incident users of AZ-EXC

Patient population, demographic, and clinical characteristics

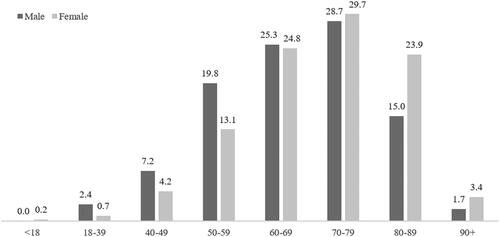

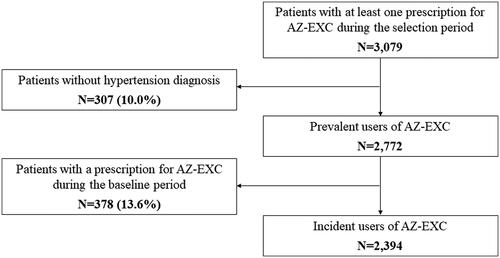

A total of 2394 hypertensive patients started treatment with AZ-EXC over the period investigated (). This was equivalent to 1.7% of the total number of patients with at least one prescription of amlodipine and/or zofenopril identified in the database during the same period (n = 142,552). The mean (SD) age was 68.6 years (12.7) and 52.6% of the population were male. Around three-quarters of patients aged between 50 and 79 years, and those between 70 and 79 years accounted for nearly 30% (). The age profile differed somewhat between males and females: lower proportions of females were found in the age classes “18–39 years” to “60–69 years,” while higher proportions were identified in the older groups ().

Figure 1. Patients attrition flow-chart for inclusion in the cohort of incident users of the extemporaneous combination AZ-EXC.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of incident users of the extemporaneous combination AZ-EXC and AZ-EXC (SM + SPC).

Mean (SD) BMI was 28.4 (5.2) kg/m2. Considering BMI classes, overweight and obese accounted for 40.6% and 31.5% of patients, respectively (). Diabetes mellitus was the most common comorbid condition (21.6% of AZ-EXC patients), followed by dyslipidaemia (18.3%), other forms of chronic ischaemic heart disease (10.5%), cardiac arrhythmia (9.3%), and gout (5.5%) (). Overall, 36% of patients (n = 860) did not present any comorbidity in the six months preceding the selection period. The most frequently co-prescribed class of drugs was represented by antithrombotic (43.0% of AZ-EXC patients) followed by lipid-lowering agents (35.9%), beta-blockers (33.7%), and RAS-antagonists (ACEi or ARB) not including zofenopril (26.9%) (). However, 16% of patients did not receive any co-prescription during the baseline period, while around 65% of the patients received two or more co-prescriptions in the same period.

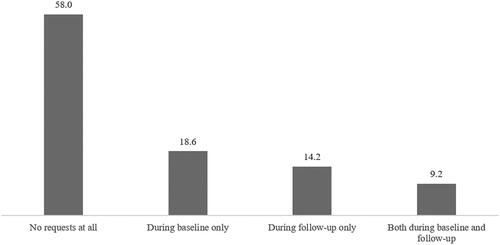

The percentage of patients requiring one cardiology outpatient visit during the six-month period following initiation of treatment with AZ-EXC was lower compared to what observed at baseline (14.2% versus 18.6%; ). Overall, more than half of patients did not need any cardiologic visit during the entire study period. However, 9.2% of patients were reported to have a referral both at baseline and follow-up period, thus before and after starting treatment with AZ-EXC ().

Treatment adherence

During the six-month period after the index date, more than half of patients on AZ-EXC treatment were reported to be low adherent (PDC <40%) to therapy, whereas 25.9% were intermediate adherent and only 19.6% were high adherent (>80%). Overall, mean (SD) PDC by the extemporaneous combination was 43.2% (30.9), while the median was 31.1%, meaning that patients were taking both molecules for 78 of 180 days (i.e. follow-up duration) ().

Table 2. Prescription adherence of incident users of the extemporaneous combination AZ-EXC and AZ-EXC (SM + SPC).

Amlodipine dose prescribed during six-month follow-up

Considering the incident users of AZ-EXC, 62.5% of the patients were prescribed only 5 mg amlodipine, while 29.4% of patients were prescribed only 10 mg amlodipine over the six months follow-up period. A small proportion of patients (around 8%) switched product dose during the period investigated ().

Table 3. Incident users of amlodipine as part of the extemporaneous combination with zofenopril stratified by strength formulation.

Prevalent users of AZ-EXC

There were 2772 prevalent users of AZ-EXC identified in the database over the period investigated. In this case, this was equivalent to 1.9% of the total number of patients with at least one prescription of amlodipine and/or zofenopril (n = 142,552). The number of prevalent users translated into an estimated 42,500 adult patients (≥18 years old) treated at the national level with the extemporaneous combination in 2019. This group is considered potentially eligible for the SPC of amlodipine and zofenopril.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis found 4068 patients meeting criteria for inclusion in the cohort of the incident users of AZ-EXC (SM + SPC) (Figure S1). Results from the analysis on this cohort were comparable to those of the incident users of AZ-EXC considering only amlodipine and zofenopril as single agents: age, sex, and BMI distributions were similar between the AZ-EXC and the AZ-EXC (SM + SPC) cohorts (). No main differences in the type of comorbidities and co-treatments were observed (). Considering prescription adherence of incident users of AZ-EXC (SM + SPC), the mean PDC was 45.1% with a median of 35.6%. Stratification of patients by prescription adherence classes based on PDC showed that 51.8% of patients had a low level of adherence, 26.7% had an intermediate level of adherence, and 21.4% had a high level of adherence (PDC ≥ 80%; ).

Furthermore, considering the incident users of amlodipine (extemporaneous combination), most patients (63.6%) were continuously prescribed 5 mg amlodipine, while 28.7% were continuously prescribed 10 mg amlodipine over the six-month follow-up period. Only a small proportion of patients (7.7%) switched product dose during the period investigated (). The number of prevalent users of the extemporaneous combination AZ-EXC (SM + SPC) was 4806. Therefore, the estimate of the number of hypertensive patients prescribed the extemporaneous combination AZ-EXC (SM + SPC) at national level in 2019 was around 75,000.

Discussion

The results of this real-world analysis of data obtained from IQVIA Italian LPD show that prescription of the extemporaneous combination of 5 mg/10 mg amlodipine and 30 mg zofenopril by Italian physicians is a consolidated treatment approach in daily practice. AZ-EXC is predominantly prescribed to overweight male patients in the age range of 60–79, being on other treatments and mainly with diabetes or dyslipidaemia. These comorbidities are the most frequent in hypertensive patients as it results also from similar studiesCitation23,Citation27.

Additional information on the AZ-EXC (SM + SPC) cohort provide a clearer picture of the well-established use of the extemporaneous combination in current practice, although patients receiving the SPC hydrochlorothiazide would not likely benefit, in terms of adherence, from the use of an amlodipine/zofenopril fixed-dose combination.

In terms of compliance to treatment, adherence to the extemporaneous combination was relatively low, and only 20% of patients were in the high PDC category when considering incident AZ-EXC patients. Overall, adherence to antihypertensive therapy is low,Citation23,Citation28,Citation29 with very low proportions of patients reported in the high adherence groups (8.1% and 11.3% shown in Italian cohorts)Citation23,Citation29. In patients with hypertension, low levels of adherence are associated not only with poorer control of BP, but also with more frequent adverse outcomes such as stroke, heart failure myocardial infarction, and deathCitation30,Citation31. Moreover, even modest changes in adherence have the potential to lead to clinically significant reductions in control of blood pressureCitation32. Poor control of hypertension is also associated with significant socioeconomic impact, including more hospital and emergency room visits and urgent hospitalizationsCitation32. This highlights the need to achieve better long-lasting control of hypertension, and many types of interventions have been proposed to increase adherenceCitation28. Among the various interventions, the use of SPCs is believed to improve adherence to treatment. In a recent analysis of hypertensive patients in Italy, 46% showed high adherence and 17% showed low adherenceCitation33. In that analysis, compared to patients initially treated with monotherapy, those receiving a SPC were less likely to be poorly adherent. In addition, a recent meta-analysis of 44 studies showed that adherence was significantly improved in patients receiving SPCs compared to free equivalent combinationsCitation34. Patients prescribed SPCs were also less likely to discontinue therapy and had significantly improved control of BP. In this regard, patients prescribed the two monotherapies would be likely to benefit more from the use of an amlodipine/zofenopril FDC, which would decrease the pill burden.

Of note, many current guidelines for hypertension recommend the use of SPCs with the aim of improving adherence. In 2013, the ESH/ESC guidelines clearly outlined the rationale for the use of SPCs stating that reducing the number of pills to be taken daily improves adherence and increases the rate of BP controlCitation35. Moreover, most SPCs mirror the drug class combinations recommended by the ESH/ESCCitation35. The most recent guidelines from the ESC/ESH issued in 2018 further advocate the use of SPCs in daily practiceCitation7. Similar guidance is also provided by the International Society of Hypertension global practice guidelines, which specify that polypharmacy should be reduced through the use of SPCs in the effort to improve adherence to antihypertensive therapyCitation36. Other guidelines such as the 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA consensus guidelines also note that there is a large body of evidence supporting the adoption of SPCsCitation37. Likewise, recommendations from Hypertension Canada state that whenever possible, SPCs should be used to improve treatment efficacy, efficiency, and tolerabilityCitation38. Thus, there is a general consensus that SPCs should be prescribed routinely in the management of hypertension in daily practice. This is even more relevant when considering that 25–35% of patients will require triple therapy to achieve control of hypertensionCitation39. Indeed, ≥2 relevant co-prescriptions in the six months leading to the start of the extemporaneous combination were recorded in 65% of patients. This suggests that the majority of patients receive a considerable pill burden and highlights the potential benefits of switching to a SPC to reduce the complexity of medical therapy.

The majority of patients were prescribed 5 mg amlodipine, as expected. However, 30–36% of the cohort was prescribed 10 mg amlodipine, which indicated that a substantial fraction is receiving a higher dose. In addition, during the six-month follow-up period, most patients were prescribed only 5 mg amlodipine (62–69%) or only 10 mg amlodipine (25–30%), and only a small proportion of patients (5–8%) switched product strength during the timeframe investigated. From a perspective of routine practice, it is important to underline that there was little need for changes in dosage in this cohort, and guidelines do not foresee seasonal variations in amlodipine treatmentCitation7.

Finally, the estimated number of adult patients treated at the national level with the extemporaneous combination in 2019 was 42,500. This proportion highlights the population that could potentially benefit from the SPC of amlodipine and zofenopril in the future.

This study has some limitations that are typical of real-world studies. First, only data on written prescriptions were available, and therefore it is assumed that any written or dispensed prescription was taken by patients. Therefore, it is possible that the true adherence to the therapeutic regimens was overestimated. Secondly, the Italian IQVIA LPD does not include information on prescriptions by private physicians. However, it should be noted that antihypertensive drugs are reimbursed by the National Healthcare System when prescribed by GPs. Thus, these estimates may be considered substantially accurate.

A further limitation is that the proportion of patients who needed a cardiologic visit may be underestimated, since visits carried out in the private sector do not require a written prescription by GPs. Additionally, the present study only explored the utilization of zofenopril in combination with amlodipine and prescription patterns regarding the use of amlodipine with other ACEis were not investigated. As a result, the adherence rates of the zofenopril plus amlodipine combination cannot be extended to other extemporaneous combinations including the same CCB together with other ACEis.

Importantly, from a clinical perspective, this real-world analysis focussed on a drug combination, zofenopril with amlodipine, which is in accordance with the recommendations of the current guidelines for the management of hypertension: to prescribe as first line a combination of a RAS blocker (e.g. an ACEi) plus a CCB in most patients. However, these two pharmacological classes include several compounds with the result that the potential extemporaneous combinations of an ACEi and a CCB used in clinical practice are multiple. At present, not all possible combinations have been evaluated in drug utilization studies based on real-world data.

To the best of our knowledge this is the first real-world study exploring the current prescribing behaviour in the clinical management of hypertensive patients treated with zofenopril and amlodipine in Italy. Indeed, the database provides information on a large number of patients, who are representative of the general Italian population. This allows a detailed and up-to-date clinical characterization of the target population in a real-world setting, expanding those information indirectly obtained from post-hoc analyses of randomized trialsCitation20 and providing more information on demographic characteristics, clinical profile, comorbidities, and concomitant medications, as reported by similar studiesCitation4.

Implications for clinical practice and future perspectives

Our findings indicate that the combination of zofenopril and amlodipine is commonly prescribed, but the rates of adherence are low. In this view, the development of SPC as substitution therapy appears a viable option to fulfil this unmet medical need by reducing low compliance and enhancing the therapeutic goals of antihypertensive therapy. Since clinical data on the efficacy and safety of this specific combination were not available, a clinical study, assessing the anti-hypertensive efficacy and safety of the combination of zofenopril 30 mg with amlodipine 5 mg or 10 mg in lowering the sitting BP after eight weeks of treatment in patients with uncontrolled BP previously treated with monotherapies, has been undertaken (NCT05279807)Citation40. The study results, not published yet, will complement the pharmacological and clinical rationale on this combination.

Finally, the data presented in this study define the size of the population prescribed with the extemporaneous combination of amlodipine and zofenopril in Italy, thus permitting estimation of the number of patients who are candidates to receive a combination of the two molecules in a SPC and to benefit from this therapeutic strategy, as recommended by the 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for HypertensionCitation7.

Conclusions

In summary, the results of this real-world analysis suggest that in Italy, the extemporaneous combination of amlodipine and zofenopril is a well-established treatment in clinical practice. Patients with comorbidities such as diabetes and dyslipidaemia, receiving concomitant medications, are likely those who may benefit the most from the introduction of SPCs, since the combination regimen represents an important strategy to increase adherence for most hypertensive patients. According to a large body of evidence collected in the last decades, zofenopril is an ACEi characterized by peculiar sulfhydryl-mediated properties, antihypertensive efficacy, cardioprotective actions and a favourable tolerability profileCitation41. Amlodipine has a well-known efficacy in achieving sustained BP control and improving clinical outcomes, complemented by a favourable tolerabilityCitation8. The development of a SPC combining these two agents appears to be a valid and rationale treatment option in the management of hypertension.

In consideration of the insufficient level of adherence seen in the present analysis and the well-known drawbacks of poor adherence to antihypertensive therapy, the development of a SPC with amlodipine and zofenopril could lead to therapeutic simplification and an increased treatment adherence, given that at present, large proportions of patients are still receiving extemporaneous combinations of monotherapy.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other relationships

RC, VP, and FH have disclosed that they are employees of IQVIA. MV declares to have been a speaker bureau and consultant for Menarini. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All named authors take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given final approval for the version to be submitted.

Supplementary_material.docx

Download MS Word (26.7 KB)Acknowledgements

Editorial support, funded by Menarini was provided by Barbara Bartolini, PhD and Patrick Moore, PhD on behalf of Health, Publishing and Services s.r.l, according to Good Publication Practice.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

i SAS Software, Version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc. (2013), Cary, NC, USA.

References

- World Health Organization. [accessed 2022 June 1]. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/media/world-health-day/public-health-problem-factsheet-2013.html.

- Tocci G, Nati G, Cricelli C, et al. Prevalence and control of hypertension in the general practice in Italy: updated analysis of a large database. J Hum Hypertens. 2017;31(4):258–262.

- Tocci G, Muiesan ML, Parati G, et al. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of blood pressure recorded From 2004 to 2014 during world hypertension day in Italy. J Clin Hypertens. 2016;18(6):551–556.

- Levi M, Pasqua A, Cricelli I, et al. Patient adherence to olmesartan/amlodipine combinations: fixed versus extemporaneous combinations. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(3):255–262.

- Mennini FS, Marcellusi A, von der Schulenburg JM, et al. Cost of poor adherence to anti-hypertensive therapy in five European countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16(1):65–72.

- Burnier M, Egan BM. Adherence in hypertension. Circ Res. 2019;124(7):1124–1140.

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021–3104.

- Murdoch D, Heel RC. Amlodipine: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use in cardiovascular disease. Drugs. 1991;41(3):478–505.

- Fares H, DiNicolantonio JJ, O’Keefe JH, et al. Amlodipine in hypertension: a first-line agent with efficacy for improving blood pressure and patient outcomes. Open Heart. 2016;3(2):e000473.

- Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Libby P, et al. Effect of antihypertensive agents on cardiovascular events in patients with coronary disease and normal blood pressure: the CAMELOT study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(18):2217–2225.

- Chrysant SG. The ALLHAT study: results and clinical implications. QJM. 2003;96(10):771–773.

- Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, et al. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(23):2417–2428.

- Dahlof B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian cardiac outcomes Trial-Blood pressure lowering arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9489):895–906.

- Miranda RD, Mion D Jr, Rocha JC, et al. An 18-week, prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter study of amlodipine/ramipril combination versus amlodipine monotherapy in the treatment of hypertension: the assessment of combination therapy of amlodipine/ramipril (ATAR) study. Clin Ther. 2008;30(9):1618–1628.

- Fogari R, Mugellini A, Derosa G. Efficacy and tolerability of candesartan cilexetil/hydrochlorothiazide and amlodipine in patients with poorly controlled mild-to-moderate essential hypertension. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2007;8(3):139–144.

- Evangelista S, Manzini S. Antioxidant and cardioprotective properties of the sulphydryl angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor zofenopril. J Int Med Res. 2005;33(1):42–54.

- Ambrosioni E. Defining the role of zofenopril in the management of hypertension and ischemic heart disorders. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2007;7(1):17–24.

- Borghi C, Cicero AF. Fixed combination of zofenopril plus hydrochlorothiazide in the management of hypertension: a review of available data. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2006;2(4):341–349.

- Guerrero-Garcia C, Rubio-Guerra AF. Combination therapy in the treatment of hypertension. DIC. 2018;7:1–9.

- Borghi C, Omboni S, Reggiardo G, et al. Efficacy of zofenopril in combination with amlodipine in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a pooled individual patient data analysis of four randomized, double-blind, controlled, prospective studies. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(10):1869–1874.

- An J, Derington CG, Luong T, et al. Fixed-dose combination medications for treating hypertension: a review of effectiveness, safety, and challenges. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2020;22(11):95.

- Ravera M, Cannavo R, Noberasco G, et al. High performance of a risk calculator that includes renal function in predicting mortality of hypertensive patients in clinical application. J Hypertens. 2014;32(6):1245–1254.

- Volpe M, Pegoraro V, Peduto I, et al. Extemporaneous combination therapy with nebivolol/zofenopril in hypertensive patients: usage in Italy. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022;38(10):1673–1681.

- IQVIA. Osservatorio sull’impatto della pandemia COVID-19 sull’accesso alle cure. Periodo dati: 2019-2020 2021 [cited 2022 Oct 24]. Available from: https://www.farmindustria.it/app/uploads/2021/03/Osservatorio-IQVIA-sullimpatto-pandemia-sullaccesso-alle-cure_Marzo-2021.pdf

- Prieto-Merino D, Mulick A, Armstrong C, et al. Estimating proportion of days covered (PDC) using real-world online medicine suppliers’ datasets. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2021;14(1):113.

- Asamoah-Boaheng M, Osei Bonsu K, Farrell J, et al. Measuring medication adherence in a population-based asthma administrative pharmacy database: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Epidemiol. 2021;13:981–1010.

- Mancia G, Volpe R, Boros S, et al. Cardiovascular risk profile and blood pressure control in Italian hypertensive patients under specialist care. J Hypertens. 2004;22(1):51–57.

- Peacock E, Krousel-Wood M. Adherence to antihypertensive therapy. Med Clin North Am. 2017;101(1):229–245.

- Mazzaglia G, Ambrosioni E, Alacqua M, et al. Adherence to antihypertensive medications and cardiovascular morbidity among newly diagnosed hypertensive patients. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1598–1605.

- Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119(23):3028–3035.

- Krousel-Wood M, Holt E, Joyce C, et al. Differences in cardiovascular disease risk when antihypertensive medication adherence is assessed by pharmacy fill versus self-report: the cohort study of medication adherence among older adults (CoSMO). J Hypertens. 2015;33(2):412–420.

- Conn VS, Ruppar TM, Chase JA, et al. Interventions to improve medication adherence in hypertensive patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2015;17(12):94.

- Rea F, Savare L, Franchi M, et al. Adherence to treatment by initial antihypertensive mono and combination therapies. Am J Hypertens. 2021;34(10):1083–1091.

- Parati G, Kjeldsen S, Coca A, et al. Adherence to single-pill versus free-equivalent combination therapy in hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2021;77(2):692–705.

- ESH ESC Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. 2013 Practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC): ESH/ESC task force for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens. 2013;31(10):1925–1938.

- Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, et al. 2020 International society of hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. J Hypertens. 2020;38(6):982–1004.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;71(19):e127–e248.

- Hypertension Canada. [accessed 2022 Jun 7]. Available from: https://guidelines.hypertension.ca/chep-resources/

- Dusing R, Waeber B, Destro M, et al. Triple-combination therapy in the treatment of hypertension: a review of the evidence. J Hum Hypertens. 2017;31(8):501–510.

- Effectiveness and safety of combination of amlodipine and zofenopril in hypertensive patients versus each monotherapy (masolino) [cited 2023 Mar 2]. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05279807

- Borghi C, Ambrosio G, Van De Borne P, et al. Zofenopril: blood pressure control and cardio-protection. Cardiol J. 2022;29(2):305–318.